15,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Oldcastle Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

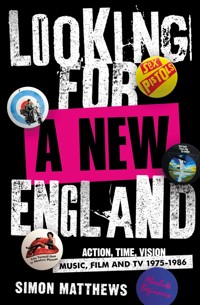

Looking for a New England covers the period 1975 to 1986, from Slade in Flame to Absolute Beginners. A carefully researched exploration of transgressive films, the career of David Bowie, dystopias, the Joan Collins ouevre, black cinema, the origins and impact of punk music, political films, comedy, how Ireland and Scotland featured on our screens and the rise of Richard Branson and a new, commercial, mainstream. The sequel to Psychedelic Celluloid, it describes over 100 film and TV productions in detail, together with their literary, social and musical influences during a time when profound changes shrank the size of the UK cinema industry.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 401

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Praise for Simon Matthews

‘Psychedelic Celluloid covers the swinging sixties in minute detail, noting the influence of pop on hundreds of productions’ – Independent

‘Addresses everything with a thoroughness and eye for detail that’s hugely impressive’ – Irish News

‘The ultimate catalogue of musical references in film and TV from the swinging sixties’ – Glass Magazine

‘Impressively comprehensive… positively jam-packed full of trivia and amusing anecdotes’ – We Are Cult

‘A must-purchase for fans of British films and pop music’ – Goldmine

‘For anyone with a love of the music, fashions, and the scene, or for anyone who simply adores movies, Psychedelic Celluloid is a handy book to own’ – Severed Cinema

1

INTRODUCTION

Most people today know what ‘Swinging London’ looked like: a visual and aural landscape where the latest clothes, the latest music, the latest cars, the latest design and the latest art were well to the fore and central to whatever was ‘happening’. This explosion of the counterculture brought a golden period in which the emerging dominance of UK pop music became bound up with hip contemporary films, both home-grown and international. A massive revolt, in fact, against the austere, shabby world of the 1940s and 1950s and a deliberate embracing of modernism that spawned a ‘pop culture’ that peaked somewhere between the release of All You Need is Love by The Beatles (’67) and the emergence of Ziggy Stardust from his chrysalis five years later. If one had to choose just one example that somehow exemplified it all, you could do a lot worse than home in on the BBC2 series Colour Me Pop, which ran from June 1968 to August 1969. Born out of the huge interest in all things pop and youth-orientated in 1967–8, it was a bolt-on accessory to Late Night Line-Up, the arts and current affairs programme broadcast from 1964–72.

Late Night Line-Up itself was produced by Rowan Ayers – father of Soft Machine’s Kevin – and usually presented by Joan Bakewell. A selection of those featured during its eight-year run reads like an alternative Sgt. Pepper-style collage: Peter Sellers, Little Richard, David Frost, the Jimi Hendrix Experience, Tony Hancock, Duke Ellington, Yoko Ono, Willy Brandt, Dave Brubeck, Otto Skorzeny, Malcolm Muggeridge, Peter Ustinov, Coco the Clown, Michael Foot, Maurice Chevalier, Ivor Cutler, Sammy Davis Junior, John Peel, Cecil Beaton, Joseph Losey, Alfred Hitchcock, Harold Pinter, Bob Hope, the men from U.N.C.L.E. (Robert Vaughn and David McCallum), playwright NF Simpson and Brigitte Bardot. This broad-brush approach, the idea that everything contemporary was part of a unified whole, was replicated in Colour Me Pop. Each week, this showcased artists filmed in a more ‘authentic’ and less staged environment than the uber-mainstream Top of the Pops, with no boundaries set about who might appear. The roster of acts appearing during its run ranged from The Tremeloes to Jethro Tull, from Bobby Hanna (deemed then by some to be ‘the next Engelbert’) to Caravan and from Gene Pitney to Giles, Giles and Fripp. All were treated as being part of the modern scene and taken seriously, too: pop now had a space of its own, late at night, on BBC2.

A harder point to pin down is when and why this type of approach ended. If 1968–9 was peak ‘Swinging London’, it was also the point, arguably, at which the contraction and demise of that world started. An example of this might be Paul and Barry Ryan, a duo with fabulous looks – they originally modelled for Vidal Sassoon – and a modest catalogue of hit singles, who signed to MGM in August 1967 for an advance of £100,000 (about £3m today), offset partly against future film appearances. They made no films and by June 1969 Barry, Paul having retired by this point, quit MGM for Polydor. Likewise, Eric Burdon, another MGM act, spent six months in LA in late 1969, fruitlessly searching for a film role: it would be 13 years before he finally got one, in Comeback, shot in West Germany in 1982. Both the Ryans and Burdon would have expected, after the huge box-office returns for A Hard Day’s Night, Help! and Blow-Up, that any half-decent UK pop artist would move automatically into films. Sadly for them, the problem at MGM in the late ’60s was that Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey took up so much studio time that suitable projects they might be considered for simply didn’t materialise.

Worse still, a number of UK films that US studios had invested in, on the basis that anything pop/counterculture and London-set would sell, failed to generate decent returns. There were few takers for The Bliss of Mrs Blossom, The Touchables, The Magic Christian, Leo the Last (in particular), Performance (whatever its later status as a cult hit), or The Ballad of Tam Lin. Nor did audiences flock to a home-grown UK production like Wonderwall, despite the involvement of Apple. Both Universal and 20th Century-Fox shut down their London offices in 1969 and MGM followed suit a year later. Neither United Artists nor Paramount did much in the UK after 1970 and all of these posted significant losses around this time as the US cinema market buckled under the impact of colour TV and the location of many old movie theatres in decaying downtown sites. With The Beatles (always the driving force in bringing US money to London after their runaway success in 1964) breaking up, the demise of The Rolling Stones Mk 1 with the death of Brian Jones, the shambles at Altamont and the death of Hendrix all occurring 1969–70, Swinging London was ending and anyone hip and fashion-conscious was moving on by the start of the new decade. There were many other indications of this. Record labels closed, notably Immediate and Marmalade, both of which released an embarrassment of riches up until their demise. Others survived but became noticeably mundane – particularly Apple, Dawn and Deram. Local film production companies either went bust or wound down as the UK replicated the diminishing box-office returns of the US. Associated British, Compton, Tigon, Hammer, Hemdale (which relocated, very profitably, to the US), British Lion and Woodfall all faded away, completely or partially, between the early ’70s and the mid-’80s. This dismal situation was only very slightly offset by the arrival of George Harrison’s HandMade Films from the wreckage of Apple in 1978.

Most startling of all, though, is the list of people who simply disappeared as the tide of optimism receded. In this pre-internet, pre-Twitter era, the roll-call of those who had vanished by the early ’70s and whom one would have thought permanent fixtures just a year or so earlier, was lengthy indeed: PP Arnold, Julie Driscoll, Peter Green (and Fleetwood Mac Mk 1), Marsha Hunt, Mary Hopkin, Paul Jones, Sandie Shaw, Dusty Springfield, Terence Stamp, Anita Pallenberg, Peter Watkins, Mike Sarne, Giorgio Gomelsky, Andrew Loog Oldham, Ronan O’Rahilly, ‘Groovy Bob’ Fraser… all once well known, all now pushed to the margins at best. There were many, many less stellar others: names which, when remembered in the mid-’70s, seemed to come from a time that suddenly seemed terribly distant.

Nor did any of the other, once vaunted, trappings of the counterculture thrive. Production of Oz, International Times and ZigZag all ceased in 1973–4, though the latter two stuttered on intermittently. Thereafter only Time Out survived, with the few scattered additions to the genre, like Gay News or Spare Rib (both of which launched in 1972), having a narrower, single-issue focus. By 1981, when City Limits, in a last hurrah for co-operative communitarianism, emerged from Time Out, the big noises in printed pop culture were Nick Logan and Robert Elms, associated with Smash Hits (’78) and The Face (’80) respectively, both of which dropped the raw anarchic politics of the counterculture and aimed instead at the wider commercial/glossy/popular market. By the mid-’80s the idea of a single overarching movement, complete with its own in-house papers and periodicals, had long gone.

Whilst this is true, and no hindsight was required then or subsequently to appreciate it, knowledge of these changes and how comprehensive they were would have implied a very metropolitan level of awareness at the time. How did people elsewhere see things? The reality was that outside London the idea of a nice tidy cut-off date for ‘the end of the ’60s’ simply didn’t apply. In ‘the provinces’, well into the ’70s many young women headed for a big night out in knee-high boots, miniskirts and beehive hair à la Jane Fonda in Barbarella; whilst their men maintained the classic hippy garb of greatcoats, tie-dye T-shirts and vast amounts of facial hair. Perhaps the career of Led Zeppelin provides us with some guidance in determining this matter. The perfect distillation of the ingredients that put the UK at the summit of pop culture in 1967–8, they still appeared invincible when their film The Song Remains the Same hit the cinema screens in 1976. By 1979, though, and their last ever gigs at Knebworth, there were arguments about how big the audiences were, why there were fewer on the second day (the promoter eventually went bust) and reviews criticising – as was the style at the time – their culture of gratuitous excess. So: for most people, did the 1960s finally end in 1977–8?

The sense of things remaining as they were and providing continuity through a period of decline was also reflected in UK cinema. In 1970, the UK produced 90 feature films and had cinema admissions totalling 193 million. These figures duly plunged: film productions down to 31 by 1980 and a nadir of 29 by 1986 with cinema admissions crashing to 101 million (1980) and 54 million (1984). Once US funding retreated and colour TV became dominant, a general view prevailed in most quarters that cinema was ‘finished’ and would soon be replaced by video, watched en famille in the safety of one’s own home, rather than in gloomy, poorly maintained town-centre Odeons, Gaumonts, ABCs and Granadas. As early as 1975, David Puttnam – whose successes by that point included That’ll Be the Day and Stardust – was in despair: ‘…Nothing good will happen while there are still cinemas that are shit heaps and critics who only like popular films when they are 30 years old….’

Thus, the main British box-office smashes of 1975–86 were respectable US entertainments like Jaws, The Towering Inferno, Star Wars, Grease, Superman and E.T., whilst in terms of locally produced megahits, the UK clung on to the remains of the increasingly threadbare Bond franchise, notably The Spy Who Loved Me and Moonraker (the latter actually a co-production with France). Otherwise, The Beatles retained some bankability as Ringo continued with his acting ventures and new albums by him and George still sold heavily in the US long after they were both semi-forgotten artists in the UK. Cinema ransacked the Lennon and McCartney catalogue for All This and World War II (’76) and a rather tired adaptation of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (’78), whilst Birth of The Beatles (’79) plumbed their origins in Hamburg. But, apart from this and 007’s annual outing, the British film industry spluttered on with occasional Carry Ons and Hammers (until 1978–9), a soft-porn slew of Confessions and Adventures (similarly discontinued circa 1978), war films, period dramas and tiny British Film Institute (BFI)-funded experimental productions that played to minuscule audiences. The earlier fashion for films that had bands and a youth angle was continued with Confessions of a Pop Performer, Never Too Young to Rock and Three for All (all ’75), but these were cheap productions that could easily have been made – minus the nudity – in the ’50s. Given this inhospitable terrain, leading directors, not surprisingly, sought solace elsewhere.

Ken Russell, arguably the only functioning UK auteur by this point, departed after Tommy and Lisztomania, making acerbic comments à la Puttnam as he went. In the years that followed, what was left of the film industry in the UK released belated sequels to ’60s hits like Percy’s Progress, Alfie Darling, Stand Up Virgin Soldiers and Revenge of the Pink Panther, as well as variousconcert films, all of which were targeted at an increasingly older audience, like TheButterfly Ball, To Russia with Elton and Give My Regards to Broad Street. Late ventures into film by Ray Davies (Return to Waterloo, ’84) and Pete Townshend (White City. ’85) appeared, but were poorly distributed and barely seen compared with the demand that work from either of these figures would have commanded 15 years earlier. Some survivors of the ’60s took a long time dying: as late as 1981 the music of The Pretty Things, in their Electric Banana guise, could be heard in the Vincent Price horror comedy The Monster Club.

By the mid-’70s, then, the UK film industry was no longer about the cutting edge, the original, or the avant-garde. Nor was it much about youth. When The Knack wowed audiences internationally in 1965, its cast had an average age of 23. A decade later, the remaining bankable UK stars were all decidedly middle-aged: Glenda Jackson, Michael Caine, Oliver Reed, Sean Connery and, greyest of them all, Roger Moore. In terms of emerging new genres, hopes were briefly pinned on pornography (or if not pornography, always difficult to define, nudity and sex) becoming respectable. Perhaps it did: after all, Emmanuelle created a long-running franchise. But in the UK the benchmark for this type of work was set instead by stuff like Confessions of a Window Cleaner (’74). Backed by Columbia, this made more money for them than The Odessa File. (Columbia was also involved with Emmanuelle). Perhaps this says it all: the French got tasteful soft-focus erotica, filmed on location with a proper budget, whilst the UK made do with a bawdy seaside postcard-style farce. A few years later, the execrable Come Play with Me (’77) had a four-year run at one West End cinema. But none of this translated into a viable rescue mission for UK film production. Films like this ultimately couldn’t compete with the hardcore material that quickly took over; nor, if one were looking for anything that explored sexuality seriously, could they rival European productions like You Are Not Alone (Denmark, ’78), Taxi zum Klo (West Germany, ’81) or Équateur (France, ’83).

As British film production declined, the remaining ‘quality’ pictures being made were often elegant period dramas. Fussy films with good attention to detail and reliable thespian performances such as A Bridge Too Far (’77), Chariots of Fire (’81), Gandhi (’82) and Greystoke: Legend of Tarzan (’84), all of which did well and by doing so reinforced a heavily nostalgic view of the UK. There were also a few US co-productions, like Clash of the Titans (’81) and a growing number of US films with some sort of limited UK connection: Logan’s Run (’76), Midnight Express (’78), 10 (’79) and Amadeus (’84). These reflected the new reality as the best bits of the UK film industry increasingly turned into a service facility for Hollywood. Perhaps we should also add to this Saturday Night Fever (’77). Written by Nik Cohn, possibly the greatest UK pop writer of his time, it was based, not on Scorsese-type delinquents, but on the Soho mods he had mixed with some years earlier.

Television suffered too, despite being the alleged cause of films’ collapse. The period between 1975 and 1986 saw a huge reduction in the amount of contemporary drama being broadcast into the nation’s living rooms. Until the mid-’70s, up to 200 scripts per year were commissioned by the three UK channels, many of these being feature film-length productions. Cut heavily from 1979, much of this was completely gone by 1985. The airtime freed up was duly allocated to less demanding fare. Game shows mushroomed; comedy too. These post-1979 broadcasting changes closely reflected the views of Mrs Thatcher, as put to Peter Hall (Director of the National Theatre and given to much radical experimentation): ‘…Why do you need public money? Andrew Lloyd Webber doesn’t….’

But, even if we accept Colour Me Pop as an apogee, its demise in 1969 initially seemed of little significance. Through 1970–71 it was replaced in the same slot by Disco 2, the formula and approach of which were broadly similar. When this, too, was ditched, it wasn’t really clear why; BBC 2 finally settled on The Old Grey Whistle Test as its sole ‘flagship’ rock music programme. This certainly was different. Unlike its predecessors, it was very serious stuff indeed, focused mainly on acts that produced albums and who gigged to a great extent on the university circuit.

The main presenter, from 1972, was Bob Harris, part DJ and part community activist – he was one of the founders of Time Out magazine – whose understated, unspectacular, non-judgemental persona was as typical of this period as the purely fictional Howard Kirk in Malcolm Bradbury’s brilliant satirical novel The History Man (’75, TV adaptation ’81). Under Harris’s stewardship a carefully circumscribed version of rock was broadcast, targeted at highly educated types in their mid-to-late twenties. Neither flash nor outrageous, this wasn’t pop, though occasional aberrations did creep through: The New York Dolls (November ’73) and Dr. Feelgood (March ’75) being notable. Between The Old Grey Whistle Test and the increasingly tawdry Top of the Pops, there were whole spectrums of music that were hardly being heard, other than occasional air play on John Peel’s nightly radio show.

Nor was this solely down to the BBC taking a view on what young people should listen to. The draining away of youthful excitement was also seen when Ronan O’Rahilly relaunched Radio Caroline in 1974. The new version had nothing in common with its earlier incarnation or his venture into films with Girl on a Motorcycle (’68 – Marianne Faithful), or, for that matter, his promotion of The MC5 at the Phun City Festival (’70). Instead, the last remaining UK pirate station churned out album-oriented FM progressive rock – a piece of the US Midwest floating a few miles off the UK coast, no less – propagating the embarrassing ‘Loving Awareness’ concept.

Within the music industry itself the only attempt at starting a significant new label by one of the majors was the Decca subsidiary UK Records. Delegated to scabrous hustler Jonathan King, this duly scored some early successes with 10cc and The Kursaal Flyers, but failed to develop further. A stronger indication of what would, eventually, become the new mainstream came in 1973, when Richard Branson, a record shop owner who emerged from the late ’60s student scene, launched Virgin. Its first release, Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells, was the ultimate hippy anthem, lauded by John Peel. More importantly, it sold: no 1 in both the UK and US, with a five-year chart run, helped enormously by its being used as part of the soundtrack for The Exorcist, the top box-office film of 1974. An example, whatever the changes, that the counterculture could still be of profitable use to the mainstream. Other Virgin successes were the West German outfits Tangerine Dream, Kraftwerk and Can. Branson also dipped a toe into the emerging dub reggae scene before memorably snapping up The Sex Pistols in 1977. But, in general terms, so staid had UK music become by the mid-’70s that rising figures in it like Dave Robinson, Jake Riviera, Ted Carroll and Roger Armstrong – band managers and, like Branson, record shop owners – were also tentatively setting up their own independent labels, following the trail blazed by John Peel with Dandelion. Relative to their output, they may not have had many hits, but Stiff (Robinson and Riviera) and Chiswick (Carroll and Armstrong) released an array of influential and highly regarded material during their existence.

The story of live music during this period was equally patchy. There were few large-scale festivals after 1972 and almost none were filmed for commercial release. The Isle of Wight hosting Hendrix and Dylan became a distant memory, whilst the Hyde Park concerts stopped in 1971, spluttered on in 1974–6, and then ceased completely. Glastonbury (a tiny version, then, of its present self) was dormant, eventually being relaunched in 1981 for an audience of new-age travellers, punks and middle-aged hippies. It would be joined, in 1982, by WOMAD, launched at nearby Shepton Mallet. Another new arrival on the block was Rock Against Racism, a spirited fightback against the antics of the far right led by a few survivors of the earlier counterculture. Sporadically successful in 1976–9, it eventually morphed into the more orthodox Labour Party-supporting Red Wedge.

Even in terms of live music venues, nothing was sacred. The Roundhouse, launching pad of so many careers, had a last hurrah in July 1976 when it staged The Flamin’ Groovies supported by The Ramones, a very significant event in the emergence of the UK punk scene. It closed in 1983, and remained shut for more than 20 years. Other notable casualties were the Lyceum and the Rainbow, both gone by 1981, followed a few years later by much of the London pub-rock circuit. Then, as education funding cuts followed, many of the colleges, universities and polytechnics – always the more lucrative end of live work – booked fewer bands and this contracted too.

And what of the music itself? Instead of being the single cultural entity shown in Colour Me Pop, by the mid-’70s it had split into three very different strands.

Firstly, amounting to about 30 per cent of what was on offer, came ongoing success by established ’60s acts – the Stones, the Who, Pink Floyd, the Faces, Rod Stewart when he went solo and innumerable UK acts trekking annually across the US – as well as newcomers who could trace their lineage back to the ’60s, but had become successful after that decade: Ace, Gilbert O’Sullivan, Alvin Stardust, Gary Glitter (both Stardust and Glitter were actually coffee-bar rockers, Shane Fenton and Paul Raven, from the late ’50s and early ’60s), Mud and The Sweet.

Secondly, and accounting for maybe as much as 50 per cent of what was heard, seen and sold: safe, officially approved pop – The Bee Gees, Olivia Newton-John, Cliff, the Lloyd Webber-Rice stuff and a huge amount of MOR tat. Included within this grouping would also be those who worked the network of cavernous working men’s clubs. Financially attractive but artistically dead, these included even the mighty Walker Brothers, who bowed out in a cabaret tour of the North and Midlands in 1978, playing weekly engagements alongside comedians and magicians.

The 20 per cent that remained was a diverse mix of anybody trying to make a new sound, those who were resolutely uncommercial but somehow kept going, the remains of the old counterculture and the start of the new. In this segment could be found Hawkwind, David Bowie, Roxy Music (all of whom sold), as well as emerging acts from the London music scene like Brinsley Schwarz and Kilburn and The High Roads (who didn’t) and, eventually, the multitude of punk and new-wave groups.

The differences among these three groupings extended even to where one bought their releases. For the first two, most of their sales took place in Woolworths, WH Smith or the gramophone and electrical goods sections of department stores. For the third and smaller group, a great deal was sold instead by small independent record shops, venues that functioned as a vital gathering point for the youth of the day and places where many of the bands hung out and where much of the music of the future had its genesis.

But even within the final third the movers and shakers of youth culture were split into a variety of discrete compartments. There were the rock and roll revivalists, seen in the documentary Born Too Late (’78); second-generation mods and enthusiasts for electronic dance music featured in Steppin’ Out (’79); a coterie of bands, mainly out of art school, and much taken with the flash US politico-rock of The MC5 and the decadence of The New York Dolls, for whom, at least some of the time, lip service was paid to notions of ‘street’ credibility; devotees of northern soul, where dancing to forgotten black American music in decrepit ballrooms and forgotten cinemas meant being part of a sect where one-upmanship and the cult of the obscure reigned; admirers of Branson’s German acts and their dreamy, trippy synthesiser heavy instrumentals; a tiny number of enthusiasts for the new dub reggae and the London-centric fans of ‘pub-rock’ (no film, but eventually compiled on the bestselling LP Hope and Anchor Front Row Festival, which reached No 28 in the UK charts in March 1978).

In cinema, the body of work that survived mirrored how pop and rock had splintered into separate compartments. But, despite the new atmosphere of conformity, interesting films and TV shows were still made that reflected the new counterculture. Among them were several showing a jaded disillusion with the music business such as Slade in Flame (’75), Rock Follies (’76), Breaking Glass (’80) and Pink Floyd: The Wall (’82). Documentarist Wolfgang Büld arrived from Munich to chronicle the changing mores in Punk in London (’77), Bored Teenagers (’79) and British Rock (’80). The leading UK bands of the time got exposure in Rude Boy and DOA (both ’80), warts-and-all studies of The Clash and The Sex Pistols respectively. The black experience in Britain was explored in Black Britannica (’78, predictably withdrawn from circulation), Babylon (’80) and Burning an Illusion (’81); whilst an increasing and sympathetic audience for gay issues and the emerging gay scene (whatever the legislation of the day allowed) brought The Naked Civil Servant (’75), Sebastiane (’76), The Alternative Miss World (’80) and My Beautiful Laundrette (’85). A range of films also appeared showing, one way or another, the general vicissitudes faced by the youth of the day, notably Jubilee (’78), Scum (’79), Gregory’s Girl (’81), Oi for England, Scrubbers and Made in Britain (all ’82). Somewhere amongst this jumble, there was a place too for The Great Rock N’ Roll Swindle (’80), Malcolm McLaren’s deliberate part-fabrication/part-pastiche about the rise and demise of The Sex Pistols with himself playing the part of a knowing, predatory ’50s-style show-business manager.

Against the odds the non-mainstream also managed to produce some box-office hits: The Rocky Horror Picture Show (’75), The Man Who Fell to Earth (’76), The Long Good Friday (’79), Quadrophenia (’79) and ThisIs Spinal Tap (’84) all appeared at this time, and one area where it certainly held sway was comedy. The rising tide of ’70s and ’80s faux sophistication and consumerism was subjected to ruthless satirical barbs in BBC TV’s Abigail’s Party (’77), whilst the later works of the Monty Python team, notably Jabberwocky (’77) and Life of Brian (’79), were big commercial hits as well as making some points about wider social and cultural issues. Peter Cook and Dudley Moore, survivors again from earlier times, re-emerged as ‘Derek and Clive’, translating very effectively to records and live shows, but less so to film. In fact, one of the lasting features of the period was the appearance of so many new UK and US comics (a number of whom were great admirers of Cook), who gradually moved into spin-off films, many of them benefits for a good cause such as The Secret Policeman’s Ball (’79). Finally, in this most ideological of times, the politics of the period were commented on via a range of dystopias in films like Memoirs of a Survivor (’81), Britannia Hospital (’82), 1984 (’84), Brazil (’85), Letter to Brezhnev (’85 – in which Merseyside is shown as being no better than a pre-glasnost Soviet Union) and Defence of the Realm (’86). But none of these, not even the few that were commercially successful, enjoyed anything like the success of Who Dares Wins (’82), in which UK and US special forces prevent dangerous political activists (‘a militant group attached to CND’) wrecking the security of the civilised world. Similarly, and to keep things in perspective, none of the bands and singers that emerged in the UK post-1975 could match Phil Collins in global sales. With a smooth, accessible persona, he emerged from the London stage version of Oliver in 1966 and then proceeded via the late psychedelic group Flaming Youth and their concept LP Ark 2 (’69) to Genesis (’71) and, eventually, a solo career that produced six No 1 albums in both the UK and US between 1980 and 1986.

The abundance of impressive US and European films during this period, and the lack of comparable UK work, ultimately came down to one thing: a shortage of money. Mechanisms had been in place in the UK since 1949 to help fund quality films. These were set up by Harold Wilson, then President of the Board of Trade, when he established the Eady Levy. Funded from cinema ticket sales, this was distributed by the British Film Fund Agency to any film that was 85 per cent shot in the UK or Commonwealth and which had no more than three non-UK people in its cast and crew. In the days of high cinema admissions (basically the ’50s and much of the ’60s until TV became truly universal), this raised significant sums. Many films, including a large number on contemporary themes, were made in the UK as a result. In fact, the Levy was so successful that when London became a fashionable swinging location, from 1965 onwards, US directors and studios deliberately filmed there so that they could tap into this funding, as well as avail themselves of much lower production costs. Later, the UK hosted a number of European giallo thrillers for much the same reason. But once ticket sales began seriously declining post-1970, and with cinemas closing in large numbers, the Eady Levy had less money to distribute and the prospect of it being used to fund imaginative, contemporary UK films faded away.

The industry was aware of this and in 1975 Wilson, now Prime Minister, came to the rescue again, setting up a working party to advise on ‘the requirements of a viable and prosperous British film industry over the next decade’. It reported in January 1976, recommending the establishment of a British Film Authority that would bring together the National Film Finance Corporation (NFFC) (also set up in 1949) and the British Film Fund Agency (BFFA), as well as the promotional and educational activities of the Department of Education and Science and the Department of Trade. Wilson specifically wanted future Eady Levy payments barred from ‘high earning’ (that is, US) films and the money from this diverted into UK ventures. The use of the UK as a cheap production base was also to be discouraged. Wilson and his civil servants were aware of the practice of US studios, when filming in the UK with Eady Levy money, of charging interest on the loans they made (to themselves) to provide the main funding for their films: thus, few such projects made a profit on paper and little or nothing was ever reinvested by the US studios back into the UK film industry. Despite resigning as Prime Minister in April 1976, Wilson continued with this project, being appointed Chair of the Interim Action Committee (IAC) on the Film Industry by his successor James Callaghan. Between 1978 and 1981, this produced five reports, with copious recommendations, none of which, after the election of the Thatcher government in 1979, was enacted. In the harsh new landscape, no new nationalised industries were going to be set up and Margaret Thatcher was not going to take advice from Harold Wilson. Wilson left Parliament in 1983, the IAC was abolished and the Eady Levy, the NFFC and the BFFA had all gone by 1985 without replacement.

This was a major blow and completed the process that had started roughly 15 years earlier: that of the avant-garde being pushed away from the foreground to a position where it was dismissed, deprived of funds and marginalised, whilst the safe, the commercial and the conventional returned to reign supreme. In short, it was a reversal of the priorities of the previous 40 years. By 1985 what would have once been made into a feature film was now lucky to be a TV play, and what would once have been a TV play might now be no more than a fringe theatre production.

Beyond the English Channel, however, there was still funding for the production of quality films and significant budgets were available for material as diverse and entertaining as Nosferatu, the Vampyre (’79, with the gnarled gargoyle-like features of Klaus Kinski and brilliant music from Popol Vuh), Fitzcarraldo (’82, Kinski again, though originally intended as a starring vehicle for Mick Jagger) and Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (’85, the ultimate, finely detailed, dystopia). Nor was this merely a question of money. Ireland, The Netherlands and France produced Light Years Away (‘81), De Lift (‘83) and Subway (’85) respectively, with plots that made imaginative use of everyday surroundings. Animation features, a particularly expensive genre, were also prominent elsewhere. Fritz the Cat and Heavy Traffic (both ’72) did well in the US, whilst in Europe Tarzoon: Shame of the Jungle (’75) was scored by the Belgian electro-pop genius Marc Moulin and Paul Fishman (who would later have, as a member of Re-Flex, the ultimate ’80s pop hit The Politics of Dancing) and Harmagedon: Genma taisen (’83, but based on a ’67 Japanese sci-fi comic) had a Keith Emerson soundtrack.

It was a shame that the UK, despite the success of Yellow Submarine (’68), provided nothing in this field. The career of ’60s wunderkind David Hemmings illustrates as well as anything how difficult it became during this period to function creatively in the UK. Departing circa 1972, around the time that his own box-office standing at home ebbed away, Hemmings migrated to Italy for Deep Red (’75), which had the type of high production values commonly seen in his earlier hits. The producers wanted Pink Floyd for the soundtrack, but had to settle instead for local Italian prog-rockers Goblin. Hemmings and Goblin were twinned again in The Heroin Busters (’77), one of a number of films that cashed in on the earlier success of The French Connection. After this came the biggest budget West German film to date: Just a Gigolo (’78) with Bowie and Dietrich, which, though ridiculed in some quarters, wasn’t all bad. Hemmings then headed to the Antipodes for Harlequin (’80, Australia), originally due to co-star Bowie and Orson Welles, neither of whom turned out to be available; Strange Behaviour (’81, New Zealand), as producer only, which featured The Birthday Party on the soundtrack, and Turkey Shoot (’82, Australia), producing again, starring Olivia Hussey, another ’60s lost soul, and set in a dystopian concentration camp run by someone called Thatcher. Hemmings’ work remained interesting, but was barely seen in the UK. Perhaps it was fitting that he wound up in Australia. By 1985, with a fully funded Film Corporation, that country was producing international hits like Crocodile Dundee and was turning out, pro rata, five times the number of films that the UK could manage.

Jane Birkin and Serge Gainsbourg, like Hemmings iconic figures just a few years earlier, also thrived in Europe. Birkin, who, after Wonderwall (’68) starred in eighteen films in six years, appeared in a further 23 from 1975–86. (In the same period Glenda Jackson made only 14.) For the diminishing band of regular UK cinema-goers, though, she was most likely noticed in stuff like Death on the Nile and Evil Under the Sun: well-upholstered adaptations of ’30s Agatha Christie thrillers. Few would have seen her in either Je t’aime, moi non plus (’76) or Egon Schiele: Excess and Punishment (’81). The former, a masterpiece that eclipsed in its exploration of sexual boundaries anything on offer in the fleapits of Soho, was set in a deliberately desolate, almost existential location with Joe Dallesandro as co-star – part of the Warhol diaspora then settling across Europe. The latter, another failed Bowie project, explored the decadent career of one of Europe’s great pre-1914 artists.

Gainsbourg, in film, was less prolific, restricting himself through this period to soundtracks (around a dozen), the most noteworthy of which were The French Woman (’77), a political thriller about call girls with Murray Head and Klaus Kinski, and French Fried Vacation (’78), an early satire about Club Med-style holidays. Being best known for the ultimate late-night smooching record (Je t’aime… a No 1 hit despite, or because of, being banned) and having scored Just Jaeckin’s Goodbye Emmanuelle, he tried his own hand at a steamy tropical erotic thriller, writing, directing and doing the music for Equateur (’83), adapted from a Georges Simenon novel. Both Birkin and Gainsbourg also had parallel careers as recording artists, turning out a series of sophisticated pop/rock albums. Most of these were made in London, but, like their films, few got a UK release. This was despite their regular backing musicians having credits that stretched from Georgie Fame, PJ Proby and Mark Wirtz, through Al Stewart, John McLaughlin, Blue Mink, Elton John and CCS to Lou Reed, David Bowie, Tangerine Dream and, eventually, Culture Club. Gainsbourg’s Rock Around the Bunker (’75, No 4 in France) and Aux Armes etc (’79, No 1 in France) were particularly noteworthy. The former was a show business musical send-up of the Third Reich à la The Producers, whilst the latter, cut in Jamaica, contained – notoriously – a reggae version of the French national anthem.

To be present and actively interested in material of this type between 1975 and 1986 meant, in the eyes of many other people, belonging to a sect: being part of a derided urban tribe with its own dress code sourced from tiny fashion kiosks, charity shops or even home-made designs. Looking back on the period now, one is conscious that understanding it is all about following the narrow threads that link the acclaimed UK pop culture of the ’60s with its wayward grandchildren of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Each thread inevitably represented a few individuals, or at best a small number of people who shaped the future, often prophets without honour in their own land. Many of these were British, some European and more than a few expatriate Americans. Most of the latter quit the US when the flower-power and protest era faded into the torpor and reaction of Nixon and Reagan: among others, Paul Theroux (whose novel The Family Arsenal, set in Deptford, brilliantly captures the London of the mid-to-late ’70s), Chrissie Hynde, Paul Morrissey and Miles Copeland III. For these the UK was cheap, cheerful and more accepting.

The greatest single continuum, of course, was David Bowie, who can, indeed, be seen in a June ’68 edition of Colour Me Pop, doing a mime to The Strawbs. An all-round entertainer, an epithet he would have appreciated as an early admirer of Tommy Steele and Anthony Newley, he was also the last UK pop star to come anywhere near having a successful film career, cruising from the critical acclaim and success of The Man Who Fell to Earth via a batch of TV and film ventures that reflect his Berlin period to an obligatory war film, a vampire thriller (The Hunger, ’83, actually a giallo about ten years late) and the final car crash of Absolute Beginners (’86), a stultifying would-be epic that failed to do anything for the UK film industry and which brings this period to a close.

Tracing the many personal histories that link Carnaby Street, Blow-Up and Yellow Submarine with Austin Powers, Cool Britannia, Brit Pop and the Young British Artists involves travelling through a submerged hinterland behind the façade of ’70s and ’80s conformity, past many failed projects, whilst, as many did at the time, looking for a new England.

2

THE LONG TAIL OF THE ’60s

Slotting the latest group or singer into a feature film where they trailed their latest single, sang the title theme, hung around in the background or even – on rare occasions – produced an entire score was normal business through the ’60s and continued to be so for some time into the next decade.

Nothing was as typical of this approach as Slade in Flame, one of the biggest box-office hits of 1975 in the UK. The group had been together since 1966 as mod-pop group The ’N Betweens and, after hooking up with Chas Chandler when he parted company from Hendrix, as skinhead hard rockers Ambrose Slade. Chandler landed them a deal with Polydor and, with the hippy thing mainly played out and many established acts avoiding the 45s market (and the constant gigging that promoting your latest release required), the group cashed in on the huge appetite for an uncomplicated guitar band. They rose to the challenge, and, with six No 1 singles and two No 1 chart albums between 1971 and 1973, comparisons with The Beatles were duly made, as was also the case then with Marc Bolan and T. Rex. As with Epstein and his charges, Chandler wanted a film project to cement their success and duly settled on the story of a group (Flame) climbing to fame, being abused by the record industry and then falling apart.

The style of previous rock/pop films is avoided, and what we get instead is a hefty dose of downbeat ’70s social realism with Slade playing the group as an amalgamation of various contemporaries they had known within the ‘beat’ scene in the West Midlands. The film is set circa 1967, but doesn’t really look at all like the period it portrays. A deal was struck with Goodtimes Enterprises to produce. Run by Sanford Lieberson and David Puttnam, their previous work included Performance, Glastonbury Fayre, The Pied Piper, That’ll Be the Day, The Final Programme, Mahler and Stardust, a hugely impressive CV. Adept at mixing rock and film, they brought in Andrew Birkin (brother of Jane) to write the script and Richard Loncraine, then 28, to direct. Prior to this, Loncraine’s only credits were a feature for the Children’s Film Foundation and a half-hour documentary about Radio One. He was perhaps better known as the designer of the ‘kinetic sculptures’ used in the film Sunday Bloody Sunday, in which he also appeared as Murray Head’s partner. By way of preparation, both Birkin and Loncraine went on tour with Slade for six weeks to see what life in a group was like. The film is really a companion piece to That’ll Be the Day and Stardust and the trio effectively form a triptych that acts as a correction to the optimism of the ’60s. The supporting cast is excellent: Tom Conti (in his first starring role), Alan Lake (Mr Diana Dors, in his best film role) and Johnny Shannon (previously in Performance). Lake, who plays the vocalist ousted from the band early on, actually had a singing career of his own at one point, releasing a fine cover of Nilsson’s Good Times in 1970. The soundtrack LP came out three months before the film, but, though selling well, failed to replicate the runaway success of earlier Slade releases, reaching No 6 UK and No 93 US. Spin-off hit singles from it included Far Far Away (No 2 UK) and How Does It Feel? (No 15 UK), both of which flopped in the US.

Reflecting the tone of the film, the world premiere was held in Newcastle upon Tyne, the home town of Chandler and his assistant (and ex-Animal) John Steel, making this very much a defiantly un-London event. Audiences in the UK liked the end result and it did well, but fared less so elsewhere. It turned out to be almost the last Goodtimes production, as the climate in the UK film industry worsened; and though Slade tried to break the US market afterwards, they failed and their UK popularity diminished quite quickly. With punk and new wave quickly ascendant, they became a semi-forgotten act, flickering back into life in 1981 and 1983–4 before finally calling it a day in 1992 – after 28 years. The film had an uncertain reception amongst critics at the time (for years it wasn’t even in Halliwell’sFilm Guide), but is highly regarded today, conveying the seediness of the music scene with some accuracy and being comparable, in style and tone, to UK TV series of the time like The Sweeney and The Professionals.

There was also – as was the case in those days – a book of the film. Written by John Pidgeon, a very significant film and music journalist, and editor of Let It Rock, a UK magazine that briefly challenged Rolling Stone; it sold 250,000 copies. Most of them would have been bought, one imagines, by the adolescents who lapped up Slade’s singles: they were not seen as a ‘cool’ act in many quarters. Like Slade, Pidgeon was a great survivor, with a career that stretched over 30 years and concluded with him producing much of the ground-breaking UK comedy of the ’90s and early ’00s – Little Britain and Steve Coogan to name but two.

Whilst audiences were flocking to Slade in Flame, the final instalment of Michelangelo Antonioni’s three-film deal with MGM appeared. Providing an interesting example of how London’s lustre faded, The Passenger completed a contract that had begun with Blow-Up, a huge commercial hit full of pop actors, locations and music, moved on to Zabriskie Point, which transferred the vibe to the US but kept some UK music (Pink Floyd) and finally wound up with a film that has not much music at all and a quietly evolving plot. As with his previous efforts, it centred on loss of identity, uncertainty about who the central character is, what motivates him or even where he is. Never a quick or prolific worker, the five-year gap between The Passenger and Zabriskie Point was explained by Antonioni accepting a commission in 1972 to do a feature-length documentary about Chairman Mao.

But… it does have a cast at the top of their game: Jack Nicholson (Easy Rider, Five Easy Pieces many others), Maria Schneider (Last Tango in Paris), Steven Berkoff and Jenny Runacre (The Final Programme). This was a rare major role for Berkoff who, at this point, was rapidly emerging as a bête noire in UK theatre with East, his play in verse about the East End of London which deployed a vast amount of swearing and violence. In the film Nicholson assumes the identity of an arms dealer, loses his own identity (a classic hippy trope, synonymous with ‘dropping out’) and ends up being killed by gangsters. A dreamy piece with absolutely brilliant visuals filmed across Spain, Germany, Algeria and London, the screenplay was by Mark Peploe, who previously did Jacques Demy’s film The Pied Piper with Donovan and the little music there was came via an uncredited Ivan Vandor.

The Passenger was not a box-office success but was critically liked. In truth, by 1975, the year Jaws swept all before it, fare of this type – the ‘European’ art movie – played to smaller, more select audiences. It is interesting to compare the careers of the main actors. Nicholson would remain an enormously significant US star for the next couple of decades, but Schneider’s career stuttered. Tired of being seen purely as a sex symbol, from here she went to Caligula, but walked out of that in 1976 and never reached – though working continuously – the heights that had been predicted for her after Last Tango in Paris. Berkoff would become one of the most industrious and interesting, not to mention provocative, figures in UK theatre and film, whilst Runacre, like Berkoff part of the new counterculture that was emerging in the UK, subsequently featured in several Derek Jarman productions.

Antonioni may have been slow in working through his obligations, but compared to Lindsay Anderson and his Travis trilogy, he was actually quite timely in completing his contract. Britannia Hospital