Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

In little over three weeks of intensive fighting, which not only witnessed the first British use of poison gas, but also the debut of New Army divisions filled with citizen volunteers, British forces at Loos managed to drive up to two miles into the German positions. However, they were unable to capitalise on their initial gains. After suffering nearly 60,000 casualties (three times the number suffered by their opponents) and being driven from the German lines in disorder, bitter recrimination followed. Nick Lloyd presents a reassessment of the Battle of Loos, arguing that it was vital to the development of new strategies and tactics. He places it within its political and strategic context, as well as discusses command and control and the tactical realities of war on the Western Front during 1915.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 678

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2008

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

LOOS

1915

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Nick Lloyd is a lecturer in the Defence Studies Department at King’s College, London, based at the Joint Services Command and Staff College in Shrivenham, Wiltshire. He was educated at the University of Birmingham, where he was founding editor of the Journal of the Centre of First World War Studies. He has taught previously at the University of Birmingham and at the Royal Air Force College in Cranwell, Lincolnshire. He lives in Cheltenham.

LOOS

1915

NICK LLOYD

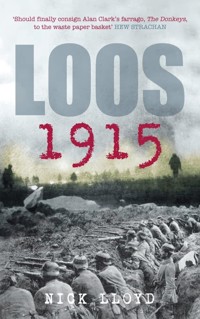

Front cover illustrations: Troops advancing to the attack through chlorine gas: a remarkable private photograph taken by a member of the London Rifle Brigade on the opening day of the battle of Loos, 25 September 1915. Courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, HU63277B. German troops in a shallow trench typical of the early years of the First World War. Courtesy of Jonathan Reeve JR920b62p193 19001950.

This edition first published 2008

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port Stroud,

Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Nick Lloyd, 2006, 2008, 2013

The right of Nick Lloyd to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9655 9

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

List of Abbreviations

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1The Origins of the Battle of Loos: May–August 1915

2Operational Planning: August–September 1915

3Pre-Battle Preparation: September 1915

4The Preliminary Bombardment: 21–24 September 1915

5The First Day (I): 25 September 1915

6The First Day (II): 25 September 1915

7The Second Day: 26 September 1915

8Renewing the Offensive: 27 September–13 October 1915

Conclusion: Loos, the BEF and the ‘Learning Curve’

Notes

Select Bibliography

Appendix I: Orders of Battle

Appendix II:Total Recorded British Deaths, 25 September 1915 and 1 July 1916

Appendix III: Senior British Officer Casualties

Maps

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

AG

Adjutant-General

AAG

Assistant Adjutant-General

ADC

Aide-de-Camp

AMS

Assistant Military Secretary

APM

Assistant Provost Marshal

Bde

Brigade

BEF

British Expeditionary Force

BGGS

Brigadier-General, General Staff

BGRA

Brigadier-General, Royal Artillery

BLL

Brotherton Library, Leeds

BLO

Bodleian Library, Oxford

CAB

Cabinet Papers

CE

Chief Engineer

CIGS

Chief of the Imperial General Staff

CGS

Chief of the General Staff

C-in-C

Commander-in-Chief

CO

Commanding Officer

CRA

Commanding Royal Artillery

CRE

Commanding Royal Engineers

DA

Deputy Adjutant

DAAG

Deputy Assistant Adjutant-General

DMO

Director of Military Operations

DMT

Director of Military Training

DSD

Director of Staff Duties

DSO

Distinguished Service Order

FOO

Forward Observation Officer

FSR

Field Service Regulations

GHQ

General Headquarters

GOC

General Officer Commanding

GQG

Grand Quartier Général (French General Headquarters)

GSOI

General Staff Officer (Grade 1)

GSO2

General Staff Officer (Grade 2)

GSO3

General Staff Officer (Grade 3)

HAR

Heavy Artillery Reserve

HE

High Explosive

HLI

Highland Light Infantry

HMSO

Her Majesty’s Stationary Office

HQ

Headquarters

IWM

Imperial War Museum

KIA

Killed in action

KOSB

King’s Own Scottish Borders

KOYLI

Kings Own Yorkshire Light Infantry

KRRC

King’s Royal Rifle Corps

LHCMA

Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives, King’s College London

MGGS

Major-General, General Staff

MGRA

Major-General, Royal Artillery

NAM

National Army Museum

NCO

Non-Commissioned Officer

OC

Officer Commanding

OHL

Oberste Heersleitung (German General Headquarters)

OP

Observation Post

OR

Other Ranks

PRO

Public Record Office

QMG

Quartermaster-General

RA

Royal Artillery

RAMC

Royal Army Medical Corps

RE

Royal Engineers

RFA

Royal Field Artillery

RFC

Royal Flying Corps

RGA

Royal Garrison Artillery

RHA

Royal Horse Artillery

TNA

The National Archives of the UK, Kew

VC

Victoria Cross

WO

War Office

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book is based upon my PhD thesis, ‘The British Expeditionary Force and the Battle of Loos’, which was completed at the University of Birmingham in July 2005. During the four years that I spent as a postgraduate student at Birmingham my supervisor, Dr John Bourne, became a personal friend. I will always be grateful to him for his constant help, support and wisdom. A special salute should be paid to Professor Peter Simkins who read through most of the drafts and provided penetrating insight, advice and much-needed encouragement. My external examiner, Professor Gary Sheffield, also deserves credit for helping to iron out a number of inconsistencies within the text. All have been a pleasure to work with.

I have learnt much from all those who have given me the benefit of their expertise during the course of this project. I am indebted to Dr Correlli Barnett, Dr Sanders Marble, Dr William Philpott and Andrew Rawson. My sincere thanks also go to Jonathan Reeve, Sophie Bradshaw and all at Tempus for agreeing to publish the manuscript and for always being supportive and helpful. Needless to say, any errors contained within this book, either of interpretation, diction or research, are mine alone.

Financial support for this project was provided by the School of Historical Studies at the University of Birmingham, which paid my tuition fees in the third year of my PhD, and the Western Front Association, which kindly awarded me a research grant.

I wish to acknowledge the generous help and assistance that I have received from the staff of the following institutions: the Bodleian Library; the Brotherton Library; the Imperial War Museum; the Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives at King’s College London; The National Archives; the National Army Museum; the Imperial War Museum; and the University of Birmingham’s Main Library.

For various acts of kindness and assistance I would like to thank the following: Matt Brosnan; Harry Buglass for the maps; Susan Campbell; Peter Cluderay; Jean Luc Gloriant; Major A.G.D. Gordon of Cape Town; the late Albert ‘Smiler’ Marshall; Nick Sedlmayr; Dr John Sneddon; Gareth Weedall; Steven Weselby; and Kate Conlin, Antje Pieper and Delia Bettaney for translating various French and German sources.

There are those without whom this book could not have been started, let alone completed. Heartfelt thanks to Tim and Tez, not only for allowing me to sleep on their sofa during my periodic visits to London, but also for watering and feeding me after long days spent in the archives. Another heartfelt dedication goes out to Louise Campbell who has been a wonderful and inspiring companion. Finally, I would like to thank my parents, John and Sue, and my late grandparents, Gladys and George, for their tireless devotion to my education and wellbeing.

Royal Air Force College, Cranwell, LincolnshireFebruary 2006

INTRODUCTION

The Battle of Loos (25 September–13 October 1915) occupies a unique place in British military history. When it took place it was the biggest land battle Britain had ever fought. It witnessed the debut on the Western Front of several New Army divisions that had been raised after the outbreak of war and was the first and only British offensive to be preceded by a discharge of cylinder-released chlorine gas and smoke. The battle was also a key moment in the rise of General Sir Douglas Haig, who replaced Field Marshal Sir John French as Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) after the battle had ended. But while these facts have been widely recognised as marking a significant milestone in the experience of the BEF, apart from the appropriate volume of the British Official History, published in 1928, Loos has failed to attract much scholarly attention.1 It remains a ‘forgotten battle’, lost in the mists of rumour, hearsay and myth.

The Battle of Loos is also important in that it defies the usual image of the First World War. It was fought before modern industrialised warfare, with its shattering artillery bombardments, had turned the Western Front into a hellish moonscape of craters and trenches, devoid of any human movement. British troops fought at Loos in flat caps with a rifle and bayonet. Although certain areas of the battlefield, particularly in the north, saw close-fought bombing actions of the type that would become so familiar to the British later on in the war, there was also fighting in woodland, on slag heaps and in built-up areas, as well as large-scale manoeuvres across the open. Many books deal with the experience of the British Army on the Western Front, but very few have concentrated on this early part of the war, with most British commentators preferring to focus on either 1916, the year of the Somme, or the Third Battle of Ypres (‘Passchendaele’) in 1917. However, the early battles of the war, particularly during 1915, defined what would happen later on as experience was gained, lessons were learnt and soldiers and politicians gradually came to terms with the revolution in warfare that they were witnessing.

Details of Loos can be found in numerous books and in various individual chapters scattered through more general pieces on the Western Front.2 Its haunting presence can also be found in a wide variety of memoirs and personal histories.3 Opinions on the battle have tended to range between the two extremes that generally characterise writing about the British Army during the First World War. The most common view is that Loos was a prime example of‘bungling’ on the part of British High Command. Indeed, it may have initially been heralded as a great victory, but as the long-desired war of movement failed to materialise and as the huge casualty returns sank in, disillusionment and disappointment were swift to emerge. Around Loos there lingers a bitter sense of futility and slaughter, only redeemed by tales of astonishing courage. While Robert Graves called the battle a ‘bloody balls-up’, the experience of another young subaltern distilled down to a feeling of utter helplessness, ‘cannon fodder’ as he called it.4 To David Lloyd George, the poor results of the battle – what he called ‘futile carnage’ – could be blamed squarely upon internal problems within the BEF, particularly the blinkered ‘military minds’ that so frustrated him.5 Captain Basil Liddell Hart agreed, calling it ‘the unwanted battle’, and Alan Clark, whose The Donkeys (1961) has perhaps been the most influential account of the fighting, wrote a bitter, if unreliable, polemic against the butchery of the British High Command and the scandalous squandering of the lives of their own men.6

This view has not gone unchallenged, however. The British Official Historian, Sir James Edmonds, saw Loos in different terms. In sharp contrast to Lloyd George and Alan Clark, Edmonds’s account emphasised the external factors that plagued the BEF during this period, such as the restrictions of coalition warfare, the lack of artillery ammunition, poorly trained officers and men, and the excellence of the Imperial Germany Army. Although Edmonds did not shrink from criticising a number of senior British commanders, most notably Sir John French, he was mainly concerned with other matters. According to him, Loos was the inevitable result of ‘using inexperienced and partly trained officers and men to do the work of soldiers, and do it with wholly insufficient material and technical equipment’. He also believed that had ‘bad luck’ and a ‘succession of accidents’ not occurred, much more could have been accomplished.7 Despite the heavy casualties and bitter disappointment, Loos was not futile. For example, Brigadier-General John Charteris, who served on the staff of First Army during the battle, emphasised its role in the ‘hard experience’ of the Western Front.8 Another staff officer, Lieutenant-Colonel J.T. Burnett-Stuart, agreed. He felt that the battle had ‘taught many lessons’, including the importance of ‘limited objective’ attacks, the movement of reserves and the handling of artillery.9 In more recent times, John Terraine has defended the capability of British High Command and stressed the ‘lack of anything approaching strategic independence’, which forced Britain to take part in a battle for which she was ill prepared and which her generals had counselled against.10 The continuing influence of these ideas can be found in two recent popular accounts: Gordon Corrigan’s The Unwanted Battle (2006) and Niall Cherry’s Most Unfavourable Ground (2005), both of which echo the conclusions first made in the British Official History.11

Which of these opposing views is correct? While the more vitriolic attacks of the ‘lions led by donkeys’ school can be safely dismissed,12 an explanation for the problems experienced by the British at Loos that relies totally upon external factors is not satisfactory, however. Indeed, not all historians have been persuaded by this line of argument. One of the most influential critics is the Canadian historian Tim Travers. Travers occupies something of a middle position between those who see the problems experienced by the BEF as primarily caused by internal problems – for example, poor command and leadership – and those who blame external factors, such as the lack of pre-war preparation, the quality of the enemy and the constrictions of coalition warfare. While agreeing that a ‘learning curve’ took place and the BEF certainly improved and developed during the war, Travers is critical of the structure and ethos of the pre-war Regular Army. According to Travers, it was rigid, dominated by factions, cliques and class, and was also curiously backward-looking. In a number of books and articles,Travers has criticised the British High Command for its reluctance to abandon an established, but out-of-date and even dangerous, mental paradigm of the ‘cult of the offensive’, which elevated the importance of character and morale in warfare above firepower and technology, with devastating consequences.13

Travers is not without his critics, however. A consistent concern is his reliance upon several ‘court gossips’ – including the correspondence of the military theorist Basil Liddell Hart – and his failure to explain the massive improvement in the BEF’s battlefield performance in 1917–18.14 Nevertheless, Travers’s findings on 1914–16 remain valid. External problems, such as lack of equipment and shells there may have been, but as numerous historians have pointed out, these were not helped by some of the curious decisions made by British High Command itself. Several examples from 1915 will suffice. The vindictive dismissal of Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien, the repeated, unnecessary and fruitless counter-attacks at the Second Battle of Ypres, and the debacle over the reserve divisions (XI Corps) at Loos point to structural failings in command and leadership within the BEF that had little to do with shell shortages or political pressure. This cannot be ignored. In 1915 the BEF was far from being the hardened meritocracy of later years, but on the other hand, it was not an army of stupid amateurs, welded to optimistic and out-of-date pre-war ideas either. It is clear that only by seeing both external and internal factors together can a true picture of events emerge.

This book will examine both how the BEF came to fight the Battle of Loos, and how it planned and executed the subsequent operation with reference to both internal and external factors. It aims to place the experience of the British at Loos firmly in the context of much recent research, including the ‘learning curve’ and ‘revolution in military affairs’,15 and seeks to shed fresh light upon some of the controversies of the battle, such as the employment of poison gas and the contentious issue of the reserve divisions. It is based mainly upon unpublished archive material, most of which is contained in archives scattered around London, such as The National Archives, the Imperial War Museum, the National Army Museum and the Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives. The personal papers of many of the key actors have been consulted at length, including those of Herbert Asquith, Sir John French and Lord Kitchener. A host of other personal papers, diaries and eyewitness accounts have been also been used. Most of the operational and tactical details from the battle stem from the army papers held in The National Archives. These sources include unit war diaries, operation orders and draft plans, and allow a close analysis of the events of the battlefield to emerge, which is untainted by later arguments and controversies. The correspondence between Sir James Edmonds and numerous veterans of Loos has also been extensively mined. These letters provide useful information on command, especially the relationships between senior officers, the ‘feel’ of the battlefield and the impact of Loos upon subsequent British offensives.

Although many of these sources have been available for nearly forty years and have been quoted briefly in some recent studies, the vast majority of the material used in this account has never been consulted previously in the context of a complete operational history of the Battle of Loos. They can, therefore, provide important and often ‘fresh’ information about the strategic complexities of the war, how the battle was planned and executed, the wider development of the BEF on the Western Front, the response of Britain’s wartime volunteers to battle, and the nature of combat during the First World War. Admittedly these sources can have drawbacks. For example, unit reports and war diaries can range in detail – from the concise to the very poor – and some tend to exaggerate the heroism of the rank and file, but they often provide an unparalleled glimpse into the operational and tactical realities of the Western Front. This study will concentrate primarily on the planning and execution of the attack at Loos from the British perspective, while the German side of operations will only be summarised briefly. Analysing the tactical performance of German units on the Western Front can be difficult because many of the battalion and brigade war diaries were destroyed in Allied bombing raids during the Second World War. However, from a consultation of the relevant regimental histories and the German Official History, both written in the 1920s, important details can be gleaned, which can aid understanding of how the British attacks progressed and why there was no decisive breakthrough.

1

THE ORIGINS OF THE BATTLEOF LOOS: MAY–AUGUST 1915

The Battle of the Marne in September 1914 cast a long shadow over the events of the following four years. The collapse of Germany’s bold bid for victory in the west, and the failure of France’s efforts to take the war to the enemy in Alsace-Lorraine, left both sides in uncharted territory. With the creation of a trench stalemate stretching from the North Sea to Switzerland, Germany and France were forced to rethink their strategies in the winter of 1914–15. After fevered debates over whether to concentrate her strength against France or Russia, Germany sanctioned increased efforts in the east and the Balkans during 1915. France, meanwhile, was left to face the devastating consequences of the loss of much of her industrial heartland and the presence of the enemy a mere five days’ march from Paris. With inactivity a politically unacceptable strategy, the French Army conducted a series of major offensives on the Western Front throughout 1915, determined to drive the invaders from the soil of France.

Beginning in late December and continuing until the end of March, the First Battle of Champagne raged on the wooded slopes between Rheims and Verdun. The French infantry, floundering heroically against the prepared German positions, desperately tried to open a big enough breach in the enemy lines to win a major strategic victory. But although much blood and ammunition was spent, the German line stubbornly refused to crack. The fighting then flickered further north. Between May and June the Second Battle of Artois was fought, and while the nature of trench warfare was beginning to become depressingly familiar, with its heavy casualties and limited gains of ground, tantalising success was achieved around Souchez and Vimy Ridge. One French corps almost reached the battle-scarred summit, before ammunition supplies dwindled, troops became exhausted and the suffocating cloak of stalemate descended once again upon the opposing positions.

The French High Command, known as Grand Quartier Général (GQG), was not, however, unduly disturbed by the events of the winter and spring. The autumn would see the culmination of France’s offensive efforts in 1915 with huge sequenced attacks in both Artois and Champagne. Aimed at striking the flanks of the German line, which bulged out around Noyon, it was hoped that these attacks would cause the collapse of the entire enemy position and restore the war of movement. This great effort required the application of not only every man and gun in the French Army, but also the assistance of her allies on the Western Front. The Belgian Army, largely locked up in the last remaining free corner of Belgium around the Yser, would be unable to help, but the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), holding a line of ever-increasing length from Ypres to Lens, would prove a valuable ally. Britain’s contribution to the autumn offensive would take the form of the Battle of Loos, a subsidiary operation fought around the northern outskirts of Lens, on the left of the French attack in Artois.

The failure of the Schlieffen Plan had profound consequences for Germany’s strategy during the First World War.1 Haunted by the prospect of a war on two fronts, which it was believed Germany could not win, it had been an article of faith for Count Alfred von Schlieffen and his successors that only by an annihilating victory in the west (Vernichtung) could victory be achieved. With France regarded as the most dangerous of the Reich’s foes, the vast bulk of Germany’s strength would be deployed in an ambitious flanking march through Belgium and northern France. It was calculated that by bringing such overwhelming strength to bear, France’s numerically weaker forces would succumb in six weeks, leaving Germany to deal with Russia’s more ponderous masses at leisure. But events had not conformed to Schlieffen’s grand design. This forced a dramatic revision in Germany’s traditional orientation. The decision in the winter of 1914–15 by the German High Command, in effect, to reverse the tenets of the Schlieffen Plan and attempt to gain victory in the east, had not been taken lightly.2 The breakdown and subsequent retirement of Colonel-General Helmuth von Moltke, Chief of the General Staff, in mid-September 1914 had brought the then War Minister, General Erich von Falkenhayn, to the fore. Falkenhayn was 54 years-old in 1915, a cold, calculating, but thoroughly modern soldier.3 Although he despaired that Germany’s failure to win a short war meant that she was now condemned to lose a long one, Falkenhayn still believed in the primacy of the Western Front. But this position was becoming under increasing criticism, especially from those officers who had experienced a different war in the east. With the spectacular tactical success of the Battle of Tannenburg (26–31 August 1914) already approaching near mythical status, the views of its chief architects, the duo of General Paul von Hindenburg and General Erich Ludendorff, could not be ignored. They believed that Russia was now Germany’s weaker foe and massive pincer movements in the east could retrieve the decisive victory lost on the Marne.4

While the backroom intrigues that surrounded the reorientation of German strategy in this period do not concern us, suffice to say Falkenhayn was extremely reluctant to divert his gaze from the west. Haunted by Napoleon’s doomed campaign against Russia in 1812, Falkenhayn dreaded his armies being sucked into the endless expanses of Poland and Ukraine. As he recorded in his memoirs, ‘Napoleon’s experiences did not invite an imitation of his example.’5 But under pressure Falkenhayn eventually gave in and agreed to renewed offensive operations in the east. The performance of German troops versus the Russians had been cause for celebration, but the weakness of Austria-Hungary had been palpable, with defeats in Galicia and Serbia sharpening the ethnic divisions in her armed forces. German reinforcements were duly dispatched eastwards. Although Falkenhayn tried to temper the grand plans of Hindenburg and Ludendorff, their operations were spectacularly successful. On 2 May 1915 the booming of a four-hour German bombardment signalled the beginning of the Gorlice-Tarnow offensive. What one historian has described as the ‘greatest single campaign of the whole war’,6 Gorlice-Tarnow precipitated the great Russian retreat of the summer. The Russian Army, crippled by unrest at home and shortages of even the most basic war materiel, could offer only spasmodic resistance. By the end of the summer, the Central Powers had advanced over 300 miles and inflicted around two million casualties on their enemy. This success then filtered down to the Balkans. On 7 October, assault troops crossed the Danube and forced the Serbs south through Montenegro and Albania. Bulgaria joined the Central Powers the same month, helping to complete the conquest of Serbia.

1915 was a year of repeated German success, but it was a bleak year for the Allies, and not only on the Western Front. Although buoyed by Italy’s declaration of war against Austria on 23 May, it soon became clear that she would not be able to achieve decisive results. The following month she began the first of eleven bloody, but inconclusive, battles of the Isonzo. Stalemate had also spread to the Mediterranean. While the oceans had long been swept of German raiders, and command of the sea was firmly back in the hands of the British Admiralty, there were some who wanted the Royal Navy to be doing more. Winston Churchill, the energetic First Lord of the Admiralty, was one of them. By the close of 1914 he had become the leading proponent of an ambitious scheme to clear the Dardanelles Straits. Strategically daring, even reckless, it imagined a swift, surgical naval strike that would clear the way to Constantinople and defeat Turkey, Germany’s main ally in the region. If a way through to the Black Sea could be made, Russia could be supplied and her surplus stores of grain exported to the west. But, as has been recounted numerous times, the Gallipoli expedition, far from being a decisive operation using ‘spare’ British naval strength, became an open, running sore that devoured ships and precious infantry divisions throughout the year. The belated Anglo-French landing at Salonika, and its swift bottling-up, only served to underline Allied powerlessness.

Debate in Germany over how the war should be won was confined to a small clique of high-ranking officers and statesmen, but the more unstable political situation in France made such a closed debate unlikely. The French Parliament, after being evacuated to Bordeaux in early September 1914, returned to Paris on 20 December, beginning ordinary sessions of parliament the following month.7 With this return to something approaching normality, French political life regained much of its zest and character. Criticism of the war effort, especially the role of the Commander-in-Chief, which had been silenced after the Union Sacrée of August 1914, gradually resurfaced as 1915 wore on. The lack of any real progress in the war, despite heavy fighting – and the catastrophic French casualties – unsettled the country and made the increasing rumours of mismanagement and incompetence, which emanated from the various sections of the war effort, intolerable. Although bitterly resented by the army, a number of parliamentary commissions were set up in 1915 and began to investigate the alleged errors and mistakes that had been made.

As it was difficult to criticise the Commander-in-Chief – most of the French newspapers were solidly pro-army – much of the discontent was directed at the Minister of War, the 56 year-old Socialist, Alexandre Millerand.8 Widely admired as a calm and determined patriot, Millerand had great political experience. During his time as War Minister in 1912–13 he had worked tirelessly to prepare the nation and her army for a war that he regarded as inevitable. Millerand believed that his primary task was to let the generals get on with the war and keep political interference to a minimum. Others, however, did not share these views. As 1915 continued, criticism of Millerand, and pressure on him to yield some of his power, gradually increased. At a meeting of the Cabinet on 27 May, Raymond Poincaré, the President of the Republic, accused Millerand of not only giving GQG too much leeway, but also ‘of ceaselessly abdicating the rights of civilian power’.9 That Millerand was too authoritarian, independent and unaccountable was also the opinion of the powerful Senate Army Commission, and with the lack of any tangible Allied victory, Millerand’s time was running out.

The Second Battle of Artois ground to a bloody halt in June; the French Tenth Army suffering over 4,000 casualties for every square kilometre it had advanced.10 Despite its failure and the unsettled political situation at home, the French Commander-in-Chief, General Joseph Jacques Cesaire Joffre, was determined that a renewed offensive in July could prove decisive. Joffre was a big man. Physically intimidating, ‘the Victor of the Marne’ was a stubborn, phlegmatic engineer, direct and intolerant, yet surprisingly calm. After making his reputation in Africa and the Far East he rose rapidly. Untouched by any trace of scandal that had so damaged the pre-war army, he became Chief of the General Staff in 1911. By the outbreak of war Joffre s imprint was firmly upon the French Army. While purging his command of officers that he did not regard as having sufficient ‘offensive spirit’, Joffre had adopted Plan XVII, a series of mobilisation orders to be followed once war broke out.11

Why did Joffre believe that a new offensive could succeed where previous ones had failed? An analysis of French strategy in this period lies beyond the scope of this study, but it is necessary to understand the principles upon which it was based. Unlike Falkenhayn, Joffre did not have the luxury of deciding where his army would fight. As Correlli Barnett has observed, the German occupation of Belgium and northern France in 1914 presented the Allies with an ‘inescapable political compulsion’ to drive the invaders out.12 Joffre recorded in his memoirs how:

The best and largest portion of the German army was on our soil, with its line of battle jutting out a mere five days’ march from the heart of France. The situation made it clear to every Frenchman that our task consisted in defeating this enemy, and driving him out of our country.13

This had been the rationale behind the heavy fighting of the winter and the larger efforts in the spring. It would again be the chief motivation for the autumn offensive. Joffre was impatient to achieve decision on the battlefield. He was aware that Frances waxing strength would reach its numerical and material peak in the autumn of 1915. If the enemy forces at present occupying northern France could not be defeated, how would the French Army be able to outfight the ten or fifteen corps that Germany could (conceivably) bring from the east in the event of a Russian collapse?

Criticism of this aggressive strategy was not long in arriving. As in Britain, there were serious misgivings in France about letting her soldiers – in Churchill’s stinging phrase – ‘chew barbed wire’ in the west. An increasing number of politicians would have preferred to defer attacking the German lines, at least until Britain’s New Armies were ready and fully equipped. On 6 August 1915, Poincaré stated in Parliament that he did not look forward to a new offensive in France and believed that the best policy to pursue was ‘active defence’. Joffre was disgusted by such an attitude. He once remarked how ‘he had certainly never dreamt of such a thing’, and that because it was ‘a form of war which was entirely negative… he was therefore wholly opposed to it’.14 It was also ‘unfair’ to France’s allies, especially Russia, then being pummelled into defeat. According to Joffre, it was ‘morally impossible not to pay heed to the appeals of our unfortunate allies’.15 Joffre was also buttressed by the sheer size of his planned operations. By early June he had sketched out plans for a much larger offensive to take place sometime in July. Instead of singular attacks either in Artois or Champagne, a concept of‘sequenced concentric attacks’ was developed.16 Joffre’s plan was a simple extension of his thoughts behind the earlier attempts to break the enemy line in the winter and spring. The flanks of the great German salient between Arras and Rheims were to be struck. A preparatory attack would initially draw off enemy reserves, before the main attack broke through the German lines, causing the collapse of the entire enemy position. Joffre believed that once this had been achieved, a war of movement would resume and Germany’s armies could be defeated in detail. As was communicated to the British, it was hoped that ‘an attack by upwards of 40 divisions on a front extending from the present left of the Tenth Army to a point some 10 kilometres South of Arras [and] an attack by some 10 divisions in Champagne’ could be arranged.17

Would this attack achieve its ambitious objectives? Considering both the strength of the German defensive positions and the weaknesses afflicting the French Army, historians have not been slow to criticise Joffre’s aggressive strategy.18 Indeed, although Millerand’s tenure as War Minister oversaw vast improvements in the production of war materiel, it could not compensate for a number of serious faults at all levels within the French Army.19 Confronted by humiliating defeat in 1870, political disarray and demoralisation over the Dreyfus Affair, and a whole series of funding crises and doctrinal confusions, by the turn of the century the French Army was suffering from a crisis of confidence. Fortified by a unifying belief in the importance of‘offensive spirit’ and ‘moral force’, however, a considerable revival had occurred by 1914. Although the extent of its pre-war ‘cult of the offensive’ has perhaps been overstated, there is little doubt that a belief in the power of the tactical attack, even into the teeth of unsuppressed enemy rifle and machine gun fire, was an important pillar of French military thought before the war.20 The Commandant of the École Supérieure de la Guerre, Colonel Ferdinand Foch (later to command Groupe d’Armées du Nord during 1915) was one of the most forceful proponents of the need to inculcate troops with sufficient ‘offensive spirit’. Although Foch and his fellow thinkers – notably the influential ‘High Priest’ of the offensive, Colonel Louis Loizeau de Grandmaison – recognised the strength of modern firepower, they believed that the most important factor in warfare was morale and having an unshakeable will to victory. If troops were imbued with such élan, which echoed an earlier, Napoleonic concept of war, it was believed that they could cross the fire-swept zone between opposing armies and take the fight to the enemy with the ‘cold steel’. Such an emphasis on the power of the offensive and morale in warfare proved resistant to change. Joffre s communiqué to his generals on the eve of the autumn offensive remained consistent with this pre-war thought. While admitting that heavy artillery was the ‘principal weapon of attack’, he explained that the ‘dash and devotion of the troops are the principle factors which make for the success of the attack’.21

The problem with such ‘offensive spirit’ was the power of modern weaponry. The great, almost exponential, increase in firepower that had occurred in the second half of the nineteenth century made closely packed infantry formations and bayonet charges extremely hazardous, even verging on the suicidal. Steady troops in entrenched positions, using breech-loading rifles, machine guns, and backed up by quick-firing artillery, were almost impossible to dislodge, without at least crippling casualties amongst the attacking troops. Indeed, the changed nature of warfare had been brutally unmasked as the French pushed into the ‘lost provinces’ of Alsace and Lorraine in the opening weeks of the war. ‘Offensive spirit’ had proved a poor substitute for adequate training, tactical skill and material superiority. A recent account records how the French Army was riddled with:

Incompetent, often elderly commanders, regimental officers too few in number for effective command and with inadequate maps, combat intelligence unreliable or incorrectly evaluated, cavalry steeped in a doctrine of sabre charges rather than reconnaissance, and infantry of reckless bravery but low tactical competence.22

Little wonder casualties were so heavy, reaching 200,000 by the end of August alone.23 The French were also seriously outgunned. Their famed 75mm quick-firing field gun was ill-suited to a war of position – the weight of shell it fired was too small to demolish fortifications or blow up enemy guns – and Germany had nearly double the number of field guns with ‘an almost total monopoly in heavy artillery’.24

The weaknesses of the French Army meant that it was simply unable to fulfil the role Joffre allocated to it. The repeated efforts throughout the year to appeal against the verdict of stalemate only served to weaken France further. While the French Army suffered over 1,430,000 casualties during 1915 and never again showed the same elan and willingness to sacrifice, the political divides in French society were put under increasing strain as the war dragged on.25 It was becoming increasingly clear that France could not win the war single-handedly. But what of France’s leading allies on the Western Front, the British?

The strategic dilemma faced by Britain during 1915, especially the debate between ‘westerners’ and ‘easterners’, has been discussed at length.26 By the close of 1914 serious and long-term decisions had to be made about Britain’s war effort. It was becoming increasingly clear that ‘business as usual’, the rather loose ethic that Britain had adopted since the outbreak of war, was not going to bring about victory. But what strategy would replace this was not immediately obvious. Would all of Britain’s strength be deployed in France in support of General Joffre, or could she still operate a historically independent strategy outside the confines of the Western Front? Because a General Staff had only been created in 1904, Britain was ill equipped with either the personnel or the administrative machinery for an informed choice to be made. The lack of detailed and precise information had the unfortunate result in a profusion of amateur strategy, personified by the meddling figure of Winston Churchill. British strategy was, therefore, often made as a response to current events and vague theories, rather than to a sober appreciation of the strength of the nation and where best this could be brought to bear.

Matters were complicated by the collapse of Prime Minister Herbert Asquith’s embattled Liberal Government in May. The formation of the Coalition on 26 May 1915, following the dual blows of the ‘Shells Scandal’ and the resignation of the First Sea Lord, Admiral Lord Fisher, reflected a growing public uneasiness over the direction of the war. The new government, still led by Asquith, may have promised a firmer, more committed prosecution of the war, but as A.J.P. Taylor acidly commented, only‘appearances were changed’.27 The new coalition was ‘from the outset a suspicious and divided body’.28 The meetings of the War Cabinet (now called the Dardanelles Committee) were more regular than they had previously been and contained more members than ever, but the decentralisation of power hampered firm decision-making. Different opinions prevailed on every matter; every matter took hours to decide. Maurice Hankey, the amiable Secretary of the Dardanelles Committee, complained that although, individually, ‘a more capable set of men could not have been got together,’ they were collectively ‘never a good team’.29

Perhaps the most outstanding member of the Cabinet was the Secretary of State for War, Field-Marshal Earl Kitchener of Khartoum.30 Kitchener was Britain’s most experienced serving soldier. An imposing, gruff, taciturn man, Kitchener had a solid bank of combat experience, organisational expertise and administrative success behind him. From the opening days of the war Kitchener believed it would last at least three years – rank heresy to the popular ‘over by Christmas’ view – and necessitate the raising of substantial reinforcements to bolster the regular army.31 Despite desiring to spend the war in Egypt, Kitchener accepted the position of Secretary of State for War on 5 August. Until his death at sea off Scapa Flow in June 1916, Kitchener worked tirelessly in the War Office, organising and administering Britain’s growing role in the war. Yet this was not without difficulty. His method of work was notoriously authoritarian and ‘oriental’. He tended to shoulder too heavy a burden, being chronically unable to delegate simpler tasks to his aides. And although he oversaw the rapid, and admittedly chaotic, expansion of the British Army and provided a vast increase in guns and shells throughout 1914–15, this was not enough to supply both the BEF and the New Armies.32

Kitchener’s strategic view of the war was always global and long-term. He wanted French and Russian forces to bear the brunt of the war in the first two years of the conflict, while Britain’s New Armies were readied and equipped. Sometime in 1916–17 – in theory – Kitcheners forces would be ready to strike the coup de grace, thus winning the war and dominating the peace. As early as 2 January 1915, Kitchener had expressed severe doubts as to the feasibility of breaking the German lines in the west.

I suppose we must now recognise that the French Army cannot make a sufficient break through the German lines of defence to cause a complete change of the situation and bring about the retreat of German forces from northern Belgium. If that is so, then the German lines in France may be looked upon as a fortress that cannot be carried by assault and also cannot be completely invested.33

His views had changed little by the summer. In a paper called ‘An Appreciation of the Military Situation in the Future’ (dated 26 June), Kitchener recognised that the war would probably last into 1916. Until then, the only area where the Allies could secure an important success was in the Dardanelles. Kitchener was therefore of the opinion that the Allies should adopt a policy of ‘active defence’ in France. He was adamant that ‘French resources in men must not be exhausted by continuous offensive operations which lead to nothing, and which possibly cause the enemy fewer casualties than those incurred by us.’34 But this caused friction. Although most of Britain’s senior politicians agreed with Kitchener (including Asquith, Churchill and Lloyd George), he was forced to balance this evident preference for operations against Turkey with continual pressure from not only the French, but also from the senior officers of the BEF, who urgently requested more drafts and equipment.

Nevertheless, from March 1915, when Britain began the operations to clear the Dardanelles Straits, events on the Western Front assumed a secondary importance. Frustrated at the uneasy stalemate persisting in France, Kitchener, supported by his Cabinet colleagues, gave priority to the attempts to knock out Turkey. The failures in Artois and the BEF’s shambolic performance at Aubers Ridge in May only served to underline the impossibility of progress in the west in the near future.35 The first meeting of the Dardanelles Committee took place on 7 June.36 It was eventually agreed that a further effort should be made in the Dardanelles. General Sir Ian Hamilton, Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force (MEF), was to be reinforced with three New Army divisions. It would allow him, given the time taken to ship the reinforcements into position, to make another big attack sometime early in August.

But what would Britain’s allies make of this? Relations between Britain and France since August 1914 had undoubtedly been close, but they were strained by mutual incomprehension and the frictions of war. Not only were the British and French bitterly split between themselves, but they also had differing wider agendas. The French were not intrinsically opposed to the Dardanelles expedition, but were never terribly enthusiastic and continually pressed for every ounce of British strength to be deployed on the Western Front. But the British shied away from such a drastic step, preferring to retain some strategic independence. The Allies were also separated by a considerable linguistic barrier; few British could speak good French and many senior French officials refused to speak English.37 These differences of opinion and temperament were clearly illustrated at the first Anglo-French conference of the war, held at Calais on 6 July 1915. Asquith’s later remark that he had ‘never heard so much bad French… in his life’ highlighted the difficulties of inter-allied co-operation during 1915. 38

The Calais Conference was one of the most important British strategic milestones of the war. Unfortunately, because no minutes were taken, what was discussed has been the subject of some confusion. It has been generally accepted that with his fluent French Lord Kitchener dominated the proceedings. In line with a Cabinet paper of 2 July, Kitchener made it clear that while the British Government was keen to sanction a renewed summer offensive in the Dardanelles, it would look gravely upon a new attack on the Western Front, preferring instead a policy of ‘active defence’.39 Although some evidence conflicts with the generally accepted version of events – notably the diary of Sir John French40 – most British accounts agree with Asquith, who believed that ‘the man who came out best, not only linguistically, but altogether, out of the thing was K[itchener]’.41 In his journal Viscount Esher, the Liberal politician, recorded how Lord Kitchener ‘delivered a most excellent oration at the meeting; so excellent that the French have wavered and are wavering’.42 Similarly, although not present at the meeting, Hankey believed Kitchener ‘was splendid and dominated the whole show’. According to him, after three hours of discussion, eight points were agreed upon.

1To continue the war of attrition.

2No great offensive on a scale which, if unsuccessful, would paralyse us for further offensives later on.

3Local offensives on a considerable scale.

4Very heavy entrenchments everywhere.

5The British to hold a longer front.

6The new armies to be sent when ready, though the Government to keep their hands free in this respect.

7The Dardanelles operation to continue.

8Diplomatic efforts to be concentrated on Romania rather than Bulgaria.43

Although most of the French Ministers had apparently been persuaded by Kitchener’s performance, Joffre’s plans for another large-scale offensive had evidently not been derailed. While most of the British delegation went away well pleased, believing that future offensives in France had been shelved, this was rejected, or at least subtly ignored, at an International Military Conference that took place at Chantilly the following day.

The International Military Conference took place at Chantilly on 7 July. Apart from Sir John French most of the British delegation was not present. Joffre dominated the meeting, saying that the war could only be decided in the large theatres and it was in the interests of the Allies that they should ‘prepare to launch a powerful offensive at the earliest possible moment’.44 Curiously, French agreed with Joffre’s sentiments – they had been discussed on 24 June45 – adding that he ‘quite agreed with General Joffre’ and would ‘assist as far he can any attack of [the] French army’.46 This startling divergence has attracted considerable attention. Why did Joffre continue to work towards a new offensive and why did Sir John ignore the expressed opinion of his government? One of Kitchener’s biographers, Philip Magnus, has suggested that the crucial event was an unofficial interview between the Secretary of State and Joffre before the Calais Conference opened. It is virtually certain that such a meeting occurred; it appears in several reliable accounts, but there is little precise information on what was discussed.47 According to Magnus, this meeting resulted in a ‘private agreement’ whereby, in order to gain Joffre’s blessing for a renewed effort in the Dardanelles, Kitchener agreed to support his offensive in France if Hamilton failed to clear a way to Constantinople.48

Kitchener and Joffre never mentioned the existence of such a pact, and it has been disputed. According to George Cassar, although a pact was not reached, a compromise was. While the BEF would be heavily reinforced, it would be spared participation in a major offensive. After an interview with Henry Wilson (Chief Liaison Officer to GQG) in late June, Kitchener had asked him whether the French would agree to support a new effort at Gallipoli. Wilson had replied that they would do so only if a large number of New Army divisions were in France by the winter.49 On this basis, therefore, Kitchener promised to send his New Armies to France, beginning with six divisions in July, to be succeeded by six more every month. If Joffre still believed that his attack must take place, it must be undertaken by the French alone.50 This view has generally been accepted but it remains problematic.51 It seems that the answer to why Calais and Chantilly were so different lies in the nature and purpose of both conferences. While Calais was the first Anglo-French conference of the war, Chantilly was merely a meeting of staffs; what David French has called ‘little more than an expression of mutual goodwill’.52 It seems that although he was firmly opposed to any new offensive on the Western Front, Kitchener agreed to let the staff discussions at Chantilly go ahead.53 After all, what harm was there in planning?

Contrary to what most historians have found, what exactly would happen in the late summer of 1915 was never explicitly decided upon. And although the New Armies would be sent to France, this was not a ‘blank cheque’, and marked only a halfway stage in a total British commitment to the Western Front. Indeed, a striking feature that emerges from the records of two conferences is the vagueness of the proceedings. British and French Governments took what they wanted from the discussions. As Maurice Hankey found out several days later, the understandings arrived at were being ‘interpreted differently in Paris to what they were in London’.54 Sir William Robertson (CGS GHQ) even informed the King’s Private Secretary, Clive Wigram, that ‘nothing very definite may be settled or can be settled between the Allies at these meetings’, but they did give a good opportunity ‘for comparing notes’.55 Similarly, at Chantilly Millerand had concluded that the conference ‘only confirms the ideas of the various commanders in chief and in no way modifies plans’.56 Allied strategy would wait upon the march of events.

The BEF may have been Britain’s most well-organised, equipped and trained army to ever set foot on foreign shores, but by the time the First Battle of Ypres had died down in November 1914, it was a pale shadow of its former glory. Largely gone were its hardened veterans; the victims of the murderous conditions of modern warfare. They had been replaced by a mixture of territorials, reservists, ‘dugouts’, the Indian Corps and individual volunteers, hurriedly trained and rushed to the front. As might have been expected, the BEF struggled to adapt to a war of unprecedented destruction. The battles it undertook in 1914–15 consumed men and munitions on a scale unimaginable before the war. A shortage of ammunition, particularly artillery shells, was the most noticeable deficit, but an array of equipment, such as shovels, sandbags and grenades, was also required for the new science of trench warfare. These shortages were not helped by the haphazard expansion of the BEF. It had gone to war in August 1914 consisting of two corps, but had grown into six corps, divided into two armies, barely five months later. During 1915 the BEF again trebled in size.57

Yet the war still had to be won. German forces were camped across most of Belgium and large expanses of northern France, and with major operations underway in the east, were going nowhere. The French were initially unimpressed by the offensive capability of the BEF, and preferred to use the British to hold stretches of the front. But they were forced to rethink this during 1915. The BEF began the first of its attempts to break through the German lines alone in March 1915 at Neuve Chapelle. The rest of its engagements (until 1917) were all conducted as part of bigger Anglo-French operations.58 During 1915 General Sir Douglas Haig’s First Army, which held the southern sector of the BEF, conducted these attacks. All were unsuccessful in that they did not break cleanly through the German lines and reach the designated objectives. An initial break-in was achieved at Neuve Chapelle (10–12 March), but German reserves skilfully stopped any further progress. Aubers Ridge (9 May) was a disaster with the infantry attack being halted on strengthened German defences, although the limited success at Festubert (15–27 May) did augur well for the future. By the end of 1915 the BEF had suffered nearly 380,000 casualties.

Nothing had prepared Field-Marshal Sir John Denton Pinkstone French, the Commander-in-Chief of the BEF, for the devastating effects of prolonged contact with the Imperial German Army.59 A soldier of immense experience and proven courage, French was widely seen as one of the greatest cavalry commanders in British history. He had been one of the few British soldiers to emerge from the South African War (1899–1902) with his reputation enhanced. His daring leadership of the Cavalry Division, especially his epic ride at Klip Drift and the subsequent relief of Kimberley, had been one of the most famous actions of the war. His post-war service was equally impressive. Between 1902 and 1907 he was GOC Aldershot, and following that he became Inspector-General of the Forces. Although he was forced to resign his appointment as Chief of the General Staff in 1914 over the Curragh incident,60 he was ideally placed to take charge of the BEF when war broke out.

Sir John was not alone in finding the strain of war difficult to cope with. By the spring of 1915 he was 62-years old and in failing health. The limitations in his character and personality were magnified by the stress of war. French was fiery, emotional and temperamental, hardly ideal qualities for a complex war in which the ability to deal with the higher demands of politics and strategy, and to co-ordinate operations alongside Britain’s allies, was of far greater importance than personal bravery or ‘dash’. His intellectual qualities were also in doubt. Although Sir John had gained a reputation after the South African War for being one of the most modern and forward-looking cavalry thinkers in the British Army, his views remained traditional. He had always been a believer in the continued relevance of traditional shock tactics for the arme blanche. He had never attended the Staff College, disliked intellectual pursuits and did not look upon ‘book-learning’ with much sympathy. French found it particularly taxing having to deal with both his political masters in London and with his allies in France. As Richard Holmes has written, ‘Sir John was chronically unsure of his position’.61 He disliked Lord Kitchener intensely, waged an on-off feud with General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien (GOC II Corps 1914 and GOC Second Army 1915), which ended with the latter’s dismissal in May 1915, and helped to engineer the ‘Shells Scandal’ that was a contributing factor in the collapse of Asquiths Liberal Government. Sir John’s relations with officers of the French Army were equally unstable. After he had discovered that Kitchener had consulted Joffre over whether to replace him in November 1914, Sir John felt understandably eager to cultivate French support. This resulted in considerable tension when Sir John was pressed to conduct operations that he thought either dangerous or unsuitable. French’s relations with the fire-eating General Ferdinand Foch (Commander Groupe d’Armées du Nord) were little better. Foch possessed a considerable influence over Sir John, often moving him from dire premonitions of disaster to wild flights of optimism.

The staff that surrounded Sir John at GHQ (based at St Omer) did their best to temper the excesses of his character, but with mixed results. French’s CGS, the blunt, straight-talking Lieutenant-General Sir William Robertson, was a soldier of rare skill and competence. His excellent performance as QMG of the BEF during 1914 has been recognised by almost all authorities.62 Although he would waver during the dark days of 1917, Robertson was always an advocate of the war on the Western Front, believing that only by ‘the defeat or exhaustion of the predominant partner in the Central Alliance’, namely Germany, could victory be achieved.63 He was suspicious of the strategic ideas of ‘easterners’ and always regarded the Western Front as the decisive theatre. But Robertson was no blind supporter of Joffre’s offensives and would have preferred more modest, ‘wearing out’ attacks on favourable parts of the German line, at least until Britain’s New Armies were fully ready to take to the field.

While Robertson was a staff officer of the first rank, who did much for the smooth running of GHQ, his relationship with Sir John was never warm, and his influence was accordingly limited. Indeed, GHQ may have contained several officers of outstanding competence – such as Brigadier-General F.B. Maurice (BGGS Operations) and Brigadier-General G.M.W. Macdonogh (BGGS Intelligence) – but its ‘diverse and often contentious mix of personalities and ideas’ meant that there were a number of mutual feuds and jealousies.64 The poisonous influence of Major-General Henry Wilson (Chief Liaison Officer to GQG) over Sir John was a continual problem. Although he had been manoeuvred out of his rather vague position of ‘sub-chief’ of the General Staff in January 1915, Wilson still possessed an intellectual dominance at GHQ. He occupied a unique position in the history of the BEF, having taken a leading role in staff discussions over the possible deployment of a British force on the left of the French Army in the event of war.65 An ardent Francophile, Wilson was widely distrusted by his own army and his murky role in the Curragh ‘Mutiny’ of March 1914 only added to his reputation as a disloyal intriguer. Robertson voiced a widely felt concern when he accused Wilson ‘of leaning too much to the side of the French and not sufficiently to the side of the army to which he belongs’.66 Vain yet ugly, awkward but confident,Wilson always remained something of an outsider within his own army.

French’s command was dictated by the brief set of instructions he had been issued with by Kitchener before embarking for France in August 1914.67 They enshrined a paradox that Sir John would feel between supporting the French and protecting the interests of the BEF. He was assured that the ‘special motive’ of the BEF was to ‘support and co-operate with the French Army against our common enemies’. Kitchener, naturally cautious and hardly thrilled at the prospect of major continental engagements, warned Sir John that because the size of his army was strictly limited, he was to look gravely upon risking his troops in forward movements, especially when large French forces were not involved. It was evident that Sir John would have to tread a thin line. While making every effort to coincide with plans of their allies, Kitchener stressed that Sir John’s command was ‘an entirely independent one’ and that under no circumstances would he come under the orders of an Allied general.

Kitchener’s orders had been vague enough in August 1914, but in the changed circumstances of spring 1915 they were beginning to look badly dated. What were Sir John’s thoughts on the situation? His views were mixed. While favouring an independent northern flank operation (the ‘Zeebrugge Plan’) to free the Channel Coast from German occupation, this was vetoed by the War Cabinet in January 1915.68 Aware that he had only kept his position because of Joffre’s support, Sir John was left with little option but to support the former’s plans for large-scale offensive operations in France. And while his moods sometimes bordered on depression, French did believe that a breakthrough in the west was possible. He had disagreed with the views expressed in Kitchener’s letter of 2 January, believing that with good weather and ample stocks of ammunition, it was possible to pierce the German lines.69