Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Ithaca Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

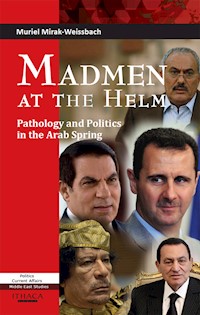

The Arab Spring was a watershed in Arab history, which gave young protesters the impetus to challenge established and entrenched dictatorial regimes for the first time, and to demand democracy. In this unique book, Muriel Mirak-Weissbach reviews specialist literature and provides a profile of the personality disorder of narcissism displayed by five leaders (Mubarak, Qaddafi, Ben Ali, Saleh and Assad), together with the related syndromes of paranoia, hysteria, and sociopathy. She argues that the responses of these leaders to the challenges they faced indicate that they were psychologically incapable of facing reality, and indeed displayed pathological symptoms in clinging fanatically to power in the face of revolt. Mirak-Weissbach considers each of the five leaders in turn, examining their behavior during the upheavals as expressed in their public statements, speeches, interviews and courses of action. Thus she identifies patterns and similarities of behavior that serve to prove that the five 'stony-faced old men in power' displayed specific pathological personality types in their responses to the political and cultural circumstances in which they were operating. A postscript to the book widens this context by identifying two cases of narcissism in contemporary American politi: George W. Bush and Sarah Palin. This highly topical, accessible and relevant book provides a psycho-historical insight into the actions and responses of the deposed dictators, viewed from a unique clinical psychological perspective.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 320

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

MADMEN AT THE HELM

Pathology and Politics in the Arab Spring

Muriel Mirak-Weissbach

MADMEN AT THE HELM

Pathology and Politics in the Arab Spring

Published by

Ithaca Press

8 Southern Court

South Street

Reading

RG1 4QS

UK

www.ithacapress.co.uk

www.twitter.com/Garnetpub

www.facebook.com/Garnetpub

blog.ithacapress.co.uk

Ithaca Press is an imprint of Garnet Publishing Ltd.

Copyright © Muriel Mirak-Weissbach, 2012

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

First Edition

ISBN: 9780863724572

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by Samantha Barden

Jacket design by Garnet Publishing

Printed by TJ International, Padstow, Cornwall

Contents

Abbreviations

Acknowledgements

Frontispiece

Introduction

1 Narcissus on the throne

2 Muammar Qaddafi: king of kings

3 Hosni Mubarak: a modern Ramses

4 Zine El-Abidine Ben Ali: all in the family

5 Ali Abdullah Saleh: a Shakespearian tragic figure

6 Bashar al-Assad: the great pretender

7 Postscript: the American Narcissus

8 The good ruler

Bibliography

Abbreviations

ABCAmerican Broadcasting CorporationASALAArmenian Secret Army for the Liberation of ArmeniaAUAfrican UnionBBCBritish Broadcasting CorporationCIACentral Intelligence AgencyCOMESTWorld Commission on the Ethics of Scientific KnowledgeDNADernières Nouvelles d’AlgérieETAEuskadi Ta Askatasuna (Basque separatist organisation)FAZFrankfurter Allgemeine ZeitungFISFront Islamique du Salut (Islamic Salvation Front)FSAFree Syrian ArmyGCCGulf Cooperation CouncilGPCGeneral People’s CongressIAEAInternational Atomic Energy AgencyICCInternational Criminal CourtIMFInternational Monetary FundIRAIrish Republican ArmyJMPJoint Meeting PartiesNATONorth Atlantic Treaty OrganisationNDPNational Democratic PartyNTCNational Transitional CouncilPFLPPopular Front for the Liberation of PalestinePFLP-GCPopular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – General CommandPNFProgressive National FrontRCDRassemblement Constitutionnel DémocratiqueSABAYemen news agencySISState Information ServiceSISMIServizio per le Informazioni e la Sicurezza Militare (Italian military intelligence service)SNCSyrian National CouncilUGTTUnion Générale Tunisienne du Travail (Tunisian General Labour Union)Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor Mohammad Seyyed Selim and Professor Elaine Hagopian for providing insightful background material as well as referring me to further sources. Dr Jack Danielian, PhD, psychologist and psychiatrist, gave me help in defining certain technical terminology and suggesting further sources in the study of personality disorders. My brother Bob again proved to be a careful and creative reader in reviewing the early drafts of this book. My thanks also to my husband, Michael, for being so supportive and maintaining an atmosphere of calm. All their contributions were vital; however, the assessments and conclusions in this study are solely those of the author.

Frontispiece

Ghadaffi:‘If we are faced with a madman like [the Jordanian King] Hussein who wants to kill his people we must send someone to seize him, handcuff him, stop him from doing what he’s doing and take him off to an asylum.’King Feisal:‘I don’t think you should call an Arab king a madman who should be taken to an asylum.’Ghadaffi:‘But all his family are mad. It’s a matter of record.’King Feisal:‘Well, perhaps all of us are mad.’Nasser:‘Sometimes when you see what is going on in the Arab world, your Majesty, I think this may be so. I suggest we appoint a doctor to examine us regularly and find out which ones are crazy.’King Feisal:‘I would like your doctor to start with me, because in view of what I see I doubt whether I shall be able to preserve my reason.’Cairo Conference, September 19701

NOTES

1 Heikal, Mohamed, The Road to Ramadan, William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd., London, 1975, p. 100.

Introduction

When, in late December 2010, thousands of Tunisians took to the streets demanding that President Zine El-Abidine Ben Ali step down and pave the way for the introduction of a representative government, most of the world gasped in disbelief and persons in high places in governments feared the worst. Yet, the ‘2011 Revolution’ succeeded – even at the cost of too many civilian lives cut short by regime bullets – and an authoritarian regime that had ruled for decades had to bow out and make room for a transitional government which would oversee elections leading to the first democratically elected parliament and government in well over a half a century.

Citizens in Egypt, energized by the Tunisian precedent, launched their own revolt and, after weeks of political mobilization, succeeded in bringing down the regime of ‘the last Pharaoh’, Hosni Mubarak. Yemen and Libya soon joined the Arab revolution and protests broke out even in the entrenched monarchies, emirates and sheikdoms of Jordan and the Persian Gulf. Syria was next to be rocked by social convulsions.

The economic–social motivations for such dramatic upheaval across the Arab world have been identified widely: high unemployment (especially among the youth, who make up the majority of the population); a widening gap between the very rich (those who have benefited from the despotic regimes’ rampant corruption and mafia-style economies) and the very poor (some, in Egypt, living on less than US$2 a day); dictatorial rule over decades, with emergency laws allowing for arbitrary arrests and lengthy detention without charges brought; torture of political prisoners, estimated to range in the tens of thousands, and so forth.

This wretched state of affairs had prevailed for decades without effective opposition. Then suddenly – or so it seemed to observers and foreign intelligence services who had not done their homework – people took to the streets. In reality, it was not at all so sudden. Opposition movements in Tunisia, Egypt and elsewhere, though savagely repressed, had not ceased to exist and, manoeuvring within the confines of police states, had managed to maintain contact with like-minded individuals and groups organized in loose networks. In Tunisia, civil society organizations had emerged and flourished, benefiting from Ben Ali’s PR campaign aimed at convincing the West that he was liberalizing his land politically. Although these associations wielded no political power, they did provide the means for citizens to come together in a social web, which would then represent the organizing energy for the revolution.

In Egypt, for over ten years opposition groups had moved into whatever space was afforded them. True, the revolution that erupted in January 2011 was triggered by events in Tunisia, but the opposition had actually been organizing itself in Egypt since 2000. The second Palestinian Intifada and the Iraq war provoked demonstrations at Cairo University between 2000 and 2004; in the following year, when parliamentary elections took place, widespread fraud occurred. The Kifaya movement came into being, after former Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamed, on a visit to Cairo, told a press conference that he had resigned as prime minister because ‘22 years are enough’. ‘Enough’ – Kifaya – became the name of a robust opposition movement to Mubarak. In 2006–2007 strikes broke out against IMF-dictated privatization; in 2006 demonstrators expressed solidarity with Lebanon and, in 2008, with Gazans against Israeli aggressions. In 2008, the April 6 youth movement came into being as a strike-support committee for workers opposing privatization programmes. Then, in 2010, when the issue of presidential elections appeared on the agenda, an ‘ElBaradei for President’ movement emerged, along with the ‘We are all Khaled Said’ movement, led by Wael Ghonim; Khaled Said is the name of an Egyptian blogger who was brutally tortured and killed by Egyptian security services in June 2010. At the same time, so-called parliamentary elections took place and were so thoroughly rigged that even the few token opposition Members of Parliament allowed to sit there found their ranks decimated. The social-economic-political climate was simmering, and all that was needed was a match to ignite the protest.1 That match was lit in Tunisia.

What triggered the uprising in Tunisia was highly symbolic. A man, though equipped with a baccalaureate, had found no other means to support his widowed mother and seven siblings than to hawk vegetables on a cart. When a policewoman controlled Mohammad Bouazizi’s papers one day and found he had no ‘licence’, she slapped him in the face, insulted his dead father and shut down his trade. Although accounts of the encounter with the policewoman have been disputed, it is confirmed that he appealed to the governor’s office for redress, and was rudely rebuffed. He doused himself with petrol, set himself on fire and died of his burns 18 days later. What might be misconstrued as the gesture of a desperate individual was in reality a tragic event epitomizing the plight of an entire population. It was the act of a man who decided to sacrifice himself to send a message to the powers that be that, to preserve his dignity as a human being, he would rather die than submit to such arbitrary humiliation. Although President Ben Ali visited the man in the hospital, no such paternalistic gesture could stem the outrage of the population.2

Bouazizi’s sacrifice will go down in history alongside the sacrifice of Czech student Jan Palach, whose self-immolation in 1969 inspired anti-communist protest, or, reaching back farther in time, certain landmarks of the American civil rights movement of the 1960s: it was the decision of one Rosa Parks to defend her dignity as a human being rather than give up her seat on a bus to a white that suddenly catalysed mass action eventually leading to the abolition of the apartheid regime against black Americans. A psychological analysis of the Bouazizi incident has characterized it as a narcissistic affront to his dignity, which was felt by the population as an affront to all, not only the individual.3

What fuelled the Egyptian revolution was this moral/political issue raised by Bouazizi. Mohammad Seyyed Selim, an Egyptian professor friend and well-known intellectual, told me in the first days of the demonstrations that what mobilized Egyptian youth was not the economic misery per se that their generation had suffered but the social and psychological degradation that accompanied it. Egyptian youth, he told me, ‘can endure deprivation, but not humiliation’. He had forecast in an article in Al Arabi on 23 January that Egypt would follow the Tunisian course because the two countries shared the same conditions. A similar phenomenon has been manifest in the various uprisings (Intifadas) by Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza: they were rejecting not only the Israeli occupation of their lands, but also the theft of their dignity as human beings.

This is the decisive subjective factor in the movement’s success: young Egyptians who launched the demonstrations showed the courage to defy the regime and its police state apparatus. After the Tunisian events, they overcame the fear that had held them and their compatriots in captive passivity over decades. When the regime responded with police attacks, and the first reports of casualties surfaced, the movement maintained the moral high ground. It did not respond with violence, but continued to expand the mobilization. Dr Gerhard Fulda, a former German diplomat who happened to be in Cairo when the revolution erupted, recalled being in Tahrir Square on the day the security police opened fire on the crowd. Although, as he told a gathering of the German–Arab Society in Berlin on 26 February, he no longer considered himself a religious man and had not visited his local church for years, he did utter a silent prayer at that moment. The gist of it was: please God let them not respond with violence. Thank God, he reported, the masses of protesters did not respond with violence, and that decided the outcome of the revolution. It was, in fact, the principled commitment to non-violent civil disobedience that determined the outcome in Tunisia and Egypt.4

The social psychology of the revolutionary process

Anyone who followed the developments over those days and weeks experienced something new on the horizon, first in Tunisia, then in Egypt. Young people were standing up for their rights and articulating their demands in unprecedented form. ‘Ben Ali must go’ shouted the protesters in Tunis; ‘Mubarak must go’ was the cry in Cairo; then, the regime must go, the emergency laws must be repealed, a new constitution and new elections must follow. In Yemen, it was: ‘Saleh, leave!’ and in Libya, ‘Down with Qaddafi!’ Syrians initially demonstrated for democratic reforms, then, after meeting with police brutality, escalated their slogans to call for regime change.

So much for the formal political demands. The power in the stance of the demonstrators derived from their willingness to put their lives on the line for the cause. What they told worldwide TV audiences via satellite stations, whether militantly or quite calmly, was: I will stay here and demonstrate until we prevail. I will stay here until I die if necessary. One young man looking straight into the camera said: ‘It’s a question of freedom or death.’ He may never have heard of the orator and politician Patrick Henry’s famous utterance ‘Give me liberty or give me death’, but he transmitted the same message. Martin Luther King believed that for a person to know what it means to be human, he must be ready to die for a cause. As he put it, ‘If a man hasn’t discovered something he will die for, he isn’t fit to live.’ In the course of the Arab revolt, the youth were discovering what it means to be human.

This constitutes a fundamental revolution in thinking. History has shown in the American civil rights movement of the 1960s, or more recently in the peaceful revolution of the East German population in 1989, that when a people declares it is ready to die for its cause, there is no weapon capable of defeating it – short of mass murder. When American civil rights leader Amelia Boynton Robinson led a march on the Alabama state capital on 7 March 1965, so that Black Americans might gain the right to vote, she and her colleagues put their lives on the line. Police on horseback, flanked by vicious dogs, attacked them ferociously in what was to become famous as Bloody Sunday. They won the right to vote.

The massacres of demonstrators in Tiananmen Square in 1989 provide a further illustration of the principle. As tanks rolled over unarmed citizens, it is estimated that somewhere between 400 and 800 people died (although reliable figures are not available). But even such repression did not work in the Arab case. In Egypt, it was more than 800 – and yet they did not desist. By April 2012, an estimated 9,000 had died in Syria. The death toll in Libya has yet to be defined. As one young Arab put it, ‘They can’t kill us all.’

The ‘new Arabs’ have been born in this historic process. They are people from all walks of life, all social strata, all religious faiths. What unites them is a revolutionary fervour to usher in a new system of government, committed to democracy and equal rights for all citizens before the law. The TV interviews with the youth document that they have assumed a new political, moral and historical identity. One told CNN and other satellite stations’ cameramen: ‘I have lived for decades in fear and trepidation; now that is gone and I finally know that I am a human being, with dignity and rights.’ One of the loudest slogans to be heard on 11 February, when Mubarak had left, was: ‘Irfa rasak, anta misri! [Hold your head high, you are an Egyptian!]’ And, as anyone watching the scenes on television could see, they were holding their heads very high. Others shouted: ‘Freedom! Civilization!’

This is the real change that has occurred. Not the ouster of a hated dictator per se – although that was the precondition – but the shift in outlook on the part of an entire population, especially the youth, who had been depressed and passive. Anyone who has visited Cairo over the past ten years as I have can recall the images of demoralization and despair. In front of every shop or public building in Cairo sat an old man in a battered kaftan, sipping tea and earning his couple of Egyptian pounds per day by ‘guarding’ the building. Serving him tea was a young Egyptian boy who should have been in school, but instead was earning a pittance by working as a pavement waiter. In front of banks, hotels and other large buildings were soldiers, police and their official vehicles. Whether it was the national television building or the headquarters of the Arab League or any ministry, everywhere the police and military maintained a very visible and, at times, intimidating presence. Hotel personnel were often obsequious, fawning over guests in hopes of a decent tip. Street vendors, like bazaaris, descended upon foreign visitors like vultures, intent on extracting whatever bounty there might be, while scrawny cats fought over tidbits fallen from a tourist’s table.

Much the same dreary scenery greeted the visitor to Tunisia. When I was there in 1994, I was shocked by the number of police and other security personnel on every block; there seemed to be more of them than there are cafés in any Italian city. And the overkill in numbers of agents deployed was responsible for a surrealistic level of intimidation of the population. A friend whom I visited then, who was a journalist and human rights activist, was so used to being overheard or taped by the omnipresent security units that she rolled down the convertible top of her car and lowered all windows before telling me in confidence how oppressive the police state regime was. Her name was Sihem Bensedrine, later to become an inspiration for the revolution.

Through their mass uprising against such oppressive rule, citizens in key Arab nations succeeded in ridding themselves of these archaic dictatorships. Not only was the Egyptian revolution a political event, but also it was a moral watershed. The same must be said of the Tunisian developments and the upsurges in Yemen, Libya and Syria. Even in Benghazi, the stronghold of the Libyan opposition, a remarkable social transformation unfolded, as citizens united in an effort to support their troops on the front. Volunteers in Benghazi breached earlier social taboos whereby women and men should work in parallel but not together, as members of both sexes rolled up their sleeves and worked side by side. Women took a leading role in organizing food rations, which would be taken by men to the fighters on the front; young men presented themselves to the volunteer women offering the assistance of their female relatives. Although Qaddafi had preached his bizarre concept of relations between the sexes in society, this was the first time that Libyan men and women had experienced equality. In Yemen, a very traditional society, women also emerged as protagonists of the movement and one of them, Tawakul Karman, received the Nobel Peace Prize for her efforts.

Youth challenges an ageing decadent order

This was the healthy side of the process.

While freedom lovers worldwide were applauding the Arab revolution, the regimes under fire were fighting for their very lives. First Ben Ali, then Mubarak, then Saleh, Qaddafi and Assad stubbornly clung to power and would not face the fact that the entire world had written them off. They categorically snubbed appeals to resign for the good of their people and nation.

The leading personalities challenged by popular uprisings share more than one common denominator. They (or their dynasties) had been in power for decades (four of them for over 30 years), and had erected repressive dictatorial regimes based on special forces, interior ministry police and intelligence agencies. They had governed through recourse to emergency rule, which allowed them to smother any whisper of opposition, hauled off opposition figures to jails where torture chambers awaited them and periodically orchestrated the charade of ‘elections’, in which the vote for the ruling elite wavered between 95 per cent and 98 per cent – results that former East German dictator Erich Honecker would have envied. Enjoying a monopoly on power, they had exploited their political status to amass vast personal fortunes through corruption, diversion of foreign aid, shares in state-controlled economic enterprise and so forth. The enormous levels of wealth brought into their private possession had been deposited variously in foreign bank accounts (later, happily, frozen by host countries).

Despite decades of oppressive police state rule their people did not lose their human dignity and, when the opportunity presented itself, they moved. It was a generational shift. The youth up to 25–30 years old, who had known literally nothing in their lifetimes but the status quo – i.e. the eternal presidents – did however know that what they experienced in daily life was not a universal phenomenon. Many of them had visited Europe or studied there, or had friends who had travelled abroad and, even if not, had access through the Internet to news about the outside world. It was this generation of young people who led the surge against the senile, antiquated regime. It was a revolt by healthy, future-oriented youth against a dying dictatorial order.

The contrast could not be more dramatic: on the one hand, thousands, then tens of thousands, then, yes, millions of citizens of all walks of life were streaming into the centre of Tunis or Cairo and Sana’a, peacefully demanding their rights not only as citizens of a specific nation but as human beings endowed with inalienable rights, citizens embracing members of the armed forces who had made the right moral choice and joined the demonstrators. AlJazeera and others broadcast images of young men brimming with pride holding up their infant children, whom they had brought to the central squares to allow them to take part in what they knew were historic events. Young girls in headscarves were filmed riding on the back of mopeds, their faces beaming with hope and their hands raised in the victory sign.

Opposite them were the stony-faced old men in power – Ben Ali, Mubarak or Saleh, or the wild-eyed Colonel Qaddafi, as well as the anomalous younger Assad, the second generation representative of an autocratic dynasty – in clinical denial of the reality their people had confronted them with, attempting, first, to appease the masses with pathetic promises of ‘reform’, then, threatening dire consequences if the protests continued, even to the point of civil war, and finally vowing to uphold their bankrupt positions of power to the bitter end. Their attitude was: après moi, le déluge and, in the extreme case of Qaddafi, the message was that, if he were to be removed from power, he would inflict the maximum damage on his people, taking as many with him to the grave as possible. Qaddafi proved true to his word, and unleashed inordinate force against his own people in a conflict that developed into a bloody civil war with tens of thousands of victims.

The bitter end came for some sooner, for others later.

In the uprisings, two diametrically opposed but mutually reinforcing social–psychological dynamics unfolded: the more the leader exerted authoritarian rule by ordering security forces to open fire on the crowd, the more the protesters mobilized, expanding their numbers by the day. The more the rebels would organize their resistance, the more intransigent the ruler would become threatening greater repression, and the more the opposition would expand its support base … and so on and so forth. And in response, the political leadership would escalate its violence, stubbornly asserting its legitimacy and power. In the process, it would lose all legitimacy and ultimately all power.

What was crucial in the cases of Tunisia and Egypt was the stance of the military. Displaying an uncanny political maturity, demonstrators appealed to the military to join them to protect them from armed assaults by the regime’s special police forces. As members of draft armies, these soldiers could not and would not obey orders to kill their own brethren. Qaddafi, apparently aware of this principle, had long since given special forces a privileged position with his regular army and later recruited mercenaries to shore up his dictatorship. In Syria, the Assad dynasty had forged a symbiosis of the army, the Ba’ath Party and the security apparatus which did not hesitate to open fire on protesters in the streets. But the time came when soldiers and officers defected and formed the Free Syrian Army. In Tunisia and Egypt, it was also sheer numbers that tipped the balance. No matter how many people the regime could assemble, no matter how many killers it could deploy, it came to the point that the protesters literally outnumbered the government forces. Continued attempts on the part of the besieged power centres to reassert political authority failed utterly, and they lost all credibility in the eyes of their people and of the world.

How the rest of the world responded was to be influential – and not always in a positive sense. Support for the opposition in Tunisia and Egypt from the West was to prove decisive, also because it was mediated through discrete channels – for example, US military contacts to Egyptian officers. On the contrary, the NATO intervention in Libya, facilitated by a United Nations Security Council resolution of dubious legality, constituted an act of military aggression that made a mockery of international law and exacerbated the civil war in the country, leading to massive civilian casualties. Similarly, when an unholy alliance of forces from Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the West coalesced around demands for military intervention against the Assad regime in Syria, this signalled the attempt to transform an initially internal conflict into a geopolitical game aimed at taking over the region and challenging the international role of China and, especially, Russia.

Revolutions are never linear and tend to become messy. Particularly in the ranks of the opposition, which are rarely homogeneous, it is difficult to determine what the political agenda of competing forces is. In the Libyan case, serious concerns arose about the legitimacy of the rebel forces, especially when they indicated no intention of dissolving their militias and submitting to a central government. In Syria, dissent within the political Syrian National Council and between it and the Free Syrian Army emerged around the issue of non-violent resistance or armed struggle. In the process of geopolitical manipulations from abroad, unsavoury foreign influences on both the SNC and FSA moved to hijack the opposition. In Egypt, after protesters had called on the military to join the movement, the provisional military council signalled its unwillingness to transfer total power to a civilian government, and the forces of the revolution rose up against its rule. At the same time, the strong electoral showing of the Salafists provoked fears of an ‘Islamization’ of society. But in every case, it was clear that, regardless of the ultimate outcome, the situation would never return to a status quo ante, and the forces that had come forward as protagonists of social change would have to work through the process leading to a new political order.

What the new order will finally look like cannot be foreseen in detail. Whether or not the victorious forces will establish their own legitimacy and earn the full trust of the people will depend on the extent to which they replace the dying, corrupt regimes with viable institutions of representative government. Thus, the treatment meted out to the ousted dictators will be a test of the moral, political and judicial legitimacy of the new leaders. If trials in Tunisia against Ben Ali et al. have fallen short of that standard, judicial proceedings against Mubarak and his ilk in Egypt also constitute a test for the provisional military governing authorities. The brutal murder of Qaddafi severely undermined the image of the rebel forces. The fate awaiting Saleh, as well as Bashar al-Assad, would reflect on the viability and legitimacy of those forces that demanded their departure. A further task facing the new leadership in all the affected countries will be to establish national unity, which will require a process of working through the tortured past, in the search for truth and national reconciliation.

Politics and pathology

To comprehend the behaviour of the Arab political leaders challenged by demands for social and political change, one must undertake a clinical examination of the psychological personality disorders present. Mubarak and Qaddafi et al. are not only discrete personalities; they also represent ‘types’ which the relevant professional psychoanalytical literature can illuminate.5In the case of the leaders of these Arab nations overtaken by revolution, we are probably dealing with several different types of personality disorder: from the narcissistic to the paranoid.

Since the ground-breaking work of Sigmund Freud, there has been a plethora of important studies published that examine various aspects of this complex matter. Psychoanalysts documented their clinical experience with cases of narcissism, paranoia, hysteria and psychopathy – all relevant phenomena to the political personalities examined here – and some researchers have directly investigated the appearance of such psychological disturbances in the realm of political life. This area of research, known as ‘psycho-historical studies’ and ‘applied psychoanalysis’, seeks to employ an understanding of pathological personality structures to specific cases of political leadership figures.6

Here, I intend to utilize the results of such studies – especially the analytical approach that they adopt – to examine the behaviour of the various heads of state in the Arab world during the revolutionary process. This study is based on the chronicle of events, and focuses on the actions, speeches and public statements of the protagonists as the dramatic events unfolded. Background material on the individual political figures, particularly regarding their family histories, childhood experiences and adult education and training, is of utmost relevance in comprehending the genesis of pathology in power.

But we are not dealing only with discrete personalities, their personal histories and careers. They are all embedded in a cultural matrix, which has seen the influence of outside forces shaping reality. The Arabs have not had an easy time of it, to put it mildly. The much sought-after Arab unity has been a chimera, largely due to the determination of the Great Powers to crush it.

After four centuries under Ottoman rule, the Arabs sought independence at the time of the First World War, but were manipulated by the European powers that pretended to back their rebellion. France and Britain signed a secret agreement, the Sykes-Picot accord, to divide up the oil-rich territory between them and, though the secret was exposed by the Soviets, the post-First World War order reflected this scheme. Most of the leaders of the newly carved Arab nations on the map were hand-picked by those European powers and functioned largely as heads of puppet states. Even when nationalist movements arose to throw off the colonial yoke, led by men who became national heroes, the new leaders rapidly introduced mechanisms for top-down control over their people and nations.

More to the point, their leaders more often than not were backed by Western powers. The Italians played a key role in Qaddafi’s 1969 coup as well as in Ben Ali’s seizure of power in 1987. Although Nasser does not fit into this category, his successor Anwar Sadat became a crucial ally of the United States through the Camp David peace with Israel, and since that time Egypt has depended on American money and backing. Yemen has enjoyed foreign backing in its fight against terrorism and the Assad dynasty had received the uncritical support of the West as a bulwark of stability in the historically unstable Middle East. The interference of the Great Powers – Great Britain, the US and France – in the new political configuration is not to be underestimated.7

Although the stimulus for the current study was provided by the 2010–2011 Arab rebellions, the analyses and conclusions are not limited to their experience. Presented in the form of a postscript is a brief reference to two cases of narcissism in contemporary American politics. On the one hand, there’s George W. Bush, whose eight-year reign betrays the indelible marks of a severe personality disorder. As the clinical study by Dr Justin Frank8 documented in detail, the US president was an emotionally disturbed individual and should never have been allowed to hold that high office in the United States. Dr Frank, a psychiatrist and Professor of Psychology at George Washington University, based his work on a professional analysis of the public statements by Bush, viewed in light of his traumatized childhood experience.

Similar psychological syndromes appear in the cases of certain American political sects and personality cults masquerading as political organizations, as well as in the relatively new phenomenon of the Tea Party movement, whose leader, Sarah Palin, offers another clinical case study.

NOTES

1 Mirak-Weissbach, Muriel, ‘The Birth of the New Egyptians’, Global Research, 15 February 2011, http://www.globalresearch.ca/index.php?context=va&aid=23231; Amin, Galal, Egypt in the Era of Hosni Mubarak 1981–2011, The American University in Cairo Press, Cairo, New York, 2011; Al Aswany, Alaa, On the State of Egypt: What Made the Revolution Inevitable, translation by Jonathan Wright, Vintage Books, Random House, New York, April 2011.

2 Bouazizi was not the first Tunisian to commit suicide as a sign of social protest, but his death precipitated events due to the popular response to it. Members of the teachers’ trade union were the ones who took the burning man to the hospital and who alerted his family. It was the UGTT unions that termed the suicide a ‘political assassination’ and formed committees that put the protest process into motion. Angrist, Michele Penner, ‘Old Grievances and New Opportunities; Understanding the Tunisian Revolution’, Middles East Studies Association (MESA) conference, Washington, DC, 3 December 2011.

3 Benslama, Fethi, Soudain la révolution! De la Tunisie au monde arabe: la signification d’un soulèvement, Éditions Denoël, Paris, 2011, cited by Silvia Marsans-Sakly, ‘The Making and Meaning of an Event’, MESA conference, ibid.

4 ‘Special Report: Inside the Egyptian Revolution’, 13 April 2011, Nonviolent Action Network; Sharp, Gene, From Dictatorship to Democracy: A Conceptual Framework for Liberation, The Albert Einstein Institution, Fourth US Edition, Boston, 2010.

5 See bibliography for references to professional psychoanalytical literature consulted.

6 Historical figures who have been examined from this standpoint include numerous Roman emperors, especially Caligula and Nero, as well as Napoleon, Mussolini, Stalin and so on.

7 The German journalist and Middle East expert Jürgen Todenhöfer, writing from Damascus in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ) on 12 December 2011, warned against international interference: ‘The attempt to reshape the Arab world through a series of piloted civil wars is the most dangerous of all solutions. For the Near East and for us.’

8 Frank, Justin A., M.D., Bush on the Couch: Inside the Mind of the President, ReganBooks, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, New York, NY, 2004, 2005.

1

Narcissus on the throne

To appreciate the conduct of the leaders of the five nations under consideration here – Tunisia, Egypt, Yemen, Libya and Syria – we need to examine them from a clinical standpoint. Political analysts from think-tanks, senior foreign correspondents and intelligence specialists worldwide will put their own particular twist on the reasons why Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak waited so long after mass demonstrations had engulfed his country before he dared speak to the nation, or why Tunisian President Zine El-Abidine Ben Ali chose to address his citizenry in the local dialect instead of classical high Arabic. Mubarak, they will say, was playing a waiting game, buying time, so to speak; and Ben Ali was merely adopting the idiom of the people, to bridge the gap between the presidency and the populace. In neither case did it work. But that is not the point.

Such explanations are, at best, naive. To grasp the reasons for the extraordinary and at times outrageous comportment of these leaders under siege, we have to leave the familiar, comfortable world of journalistic clichés and delve into the realm of clinical psychology – to be more precise, applied psychoanalysis. No matter what immediate political considerations might appear to motivate the leader’s move at any point along the way, it is deep-rooted psychological factors that can more fully explain the words and actions of these individuals.

In most of the cases under consideration here, we are dealing with what clinical psychoanalytical literature calls the narcissistic personality. As first analysed by Sigmund Freud, not only is narcissism a pathological manifestation that can appear in diverse personality types, but also it is most frequently encountered among political figures, especially those elevated to a position of power.1 Narcissism and power, as we shall discover, are closely related; on the one hand, the narcissistic personality strives to attain power in order to satisfy a pathological need for admiration, recognition and love, and, on the other hand, even the ‘normal’ person who comes to occupy a position of power may tend, as a result, to develop narcissistic traits as a quasi-‘natural’ expression of his political function.

Where does the term come from? Ancient Greek lore relates the myth of one Narcissus, a 16-year-old whose extraordinary beauty overwhelmed other youth and even himself. Echo, a nymph, was one of the many who fell in love with the handsome young man. As her name indicates, she echoed the words of others, but could not speak herself. She tried once to offer her love to Narcissus, but out of pride he rejected her, and she ultimately turned into stone. One day while he was out hunting, Narcissus looked for water to quench his thirst, and came upon a spring. When he knelt down and looked into the water, he saw his reflection and fell in love with it. Vainly he kissed the water, only to realize this was a mirror image of himself. After pining away for this impossible love, Narcissus died, and a flower by that name grew where he perished.2