Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

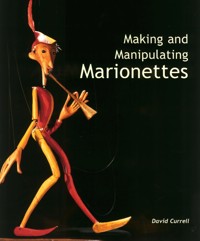

Making and Manipulating Marionettes is a comprehensive guide to the design, construction and control of string puppets, a craft and performance art that has fascinated audiences for over two thousand years. Topics covered include: An introduction to the marionette tradition and the principles and practicalities of marionette design Advice on materials and methods for carving, modelling and casting puppet parts Step-by-step instructions for the construction of human and animal marionettes using traditional techniques and latest materials Detailed explanations for marionette control, stringing and manipulation Secrets for achieving a wide range of special effects and traditional acts, tricks and transformations

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 295

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2004

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘Bubbles’ by Paul Doran, Shadowstring Theatre

First published in 2004 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2024

This impression 2018

© David Currell 2004

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7198 4356 3

To the memory of my father, Leonard Currell, whose encouragement and support in my childhood fostered my interest in crafts and design. We worked together on my first marionette before his early death.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

1 The Marionette Tradition

2 Marionette Design

3 Heads – Materials and Methods

4 Construction and Costume

5 Control and Manipulation

6 Animal Marionettes

7 Specialized Stringing

8 Specialized Designs

Useful Addresses

Index

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Puppeteers are renowned for their willingness to share techniques and the secrets of their creations, none more so than those who have contributed to this book and to whom I am particularly grateful. Gordon Staight introduced me to the magic of marionettes, spent countless hours over many years teaching me his techniques, and shared the clever, but often simple, ways in which he surprised and amazed his audiences. Paul Doran welcomed me to his theatre and allowed me to delve into all aspects of his marionettes’ construction and performance. Gren Middleton and John Roberts have supplied photographs of their beautiful marionettes and freely shared technical information. Lyndie Wright has allowed me use of photos of the work of the late John Wright, OBE, whose work I always admired. The Puppet Centre has also allowed me to photograph items in its splendid and important collection. Further details about these contributors are included in the Appendices.

Over the years I have also been involved closely with major puppet theatre organisations, especially the Puppet Centre in London, the British Section of UNIMA (Union Internationale de la Marionnette), and the British Puppet and Model Theatre Guild, through which I have been entertained, learned a host of techniques, and made many friends, too numerous to mention here.

I am extremely grateful also to Ian Howes for photographs of some of my work in progress, and to my friends and colleagues at Roehampton University, David Rose and Robert Watts, David for photographs of figures in my troupe and the Puppet Centre Collection, and Robert for assistance with the numerous illustrations.

Specialized puppetry techniques, like conjuring tricks, generally come down to a set of a few basic principles. Methods and materials might develop but the principles themselves are timeless. So the reader will find in this book many techniques that I learned with Gordon Staight, both of us depending heavily on a few classics of puppet lierature, all published by Wells Gardner, Darton & Co Ltd. In particular, we found inspiration in Everybody’s Marionette Book (1948), Animal Puppetry (1948), A Bench Book of Puppetry (1957) and A Second Bench Book of Puppetry (1957), all by H.W. Whanslaw, and Specialised Puppetry (1948) by H.W. Whanslaw and Victor Hotchkiss. Later I also found useful ideas in Puppet Circus (1971) by Peter Fraser (B.T. Batsford Ltd). Those familiar with these works will recognise that a few of my illustrations, sketched for my own puppets, are based upon drawings in these books. I gratefully acknowledge these sources of information and inspiration.

Last but not least, my thanks are extended to the team at The Crowood Press for their support, patience and helpful suggestions, shaping this into a clear, colourful and attractive book that I trust the reader will enjoy as much I as I have writing it.

PHOTO CREDITS

All photos of Movingstage Marionettes: Gren Middleton.

Photos of PuppetCraft: John Roberts, except pages 20 (left), 68; these are courtesy of John Roberts and Graham Hodgson.

Photos of Shadowstring Theatre/Paul Doran: David Currell, courtesy Paul Doran, except: page 13 (right), courtesy Paul Doran; page 101, Steve Guscott, courtesy Paul Doran.

Photos of Gordon Staight’s marionettes: David Currell (author’s collection).

Photos from Puppet Centre Collection, pages 9, 19 (left), 26, 97, 98: David Rose, courtesy Puppet Centre Ltd.

Photos from Puppet Centre Collection, pages 11, 18, 34 (left), 48, 65, 78, 160: David Currell, courtesy Puppet Centre Ltd.

Image page 10: Steve Finch, courtesy Puppet Centre Trust, Jim Henson Productions and Salford Museum & Art Gallery

Image page 17 (left): courtesy Puppet Centre Ltd (Crafts Council Collection).

Image page 19 (right): courtesy John Blundall.

Image pages 55 and 69: courtesy Lyndie Wright.

Image page 57: courtesy Albrecht Roser, Stuttgart, Germany.

Image page 71: courtesy Christopher Leith.

Photos of author at work, pages 24, 25, 40: Ian Howes.

All other photos (author’s collection): David Currell, except pages 33, 47, 93: David Rose; 89, 92: Emre Currell; 180, 183: Emily Currell.

1 THE MARIONETTE TRADITION

The term ‘marionette’ is used in English specifically for string puppets, to be distinguished from the French marionnette, which is a generic term for all types of puppet. While it is widely agreed that ‘puppet’ is derived from pupa, the Italian for doll, the origin of ‘marionette’ is uncertain. Some writers suggest that it derives from ‘little Mary’, referring to the use of puppets in churches.

Orlando Furioso, a Sicilian rod-marionette, carved in wood with beaten armour.

Marionettes have a long, sometimes distinguished, history. It is quite possible that early types of marionette included figures used in fertility rites; others, operated remotely by strings, were used in ancient temples to inspire the congregation with wonder. In some cultures, marionettes were in use before human actors because of religious taboos on impersonation. In Indian Sanskrit plays, for example, the leading player is called sutradhara or ‘the holder of strings’ because he was originally a marionette operator. Early marionette performances in India took their themes from the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, the great Sanskrit epics, the contents of which are well suited to puppet theatre.

A traditional Burmese marionette in the Puppet Centre collection.

We know that marionettes were in use in China by the eighth century but the Greeks might have used puppets as early as 800BC. References to marionettes appear in Roman literature by 400BC, by which time it was certainly a common form of entertainment in Greece.

There appears to be no documentary evidence of the puppet show between the fall of Rome and the seventh century but it seems reasonable to assume that vestiges of this dramatic tradition survived, for between the seventh and ninth centuries we find puppets being used for religious purposes.

We can trace the use of puppets in Britain back to the fourteenth century, possibly introduced by French entertainers in the previous century, and we know also that marionettes were in use in Elizabethan England.

The puppet theatre was patronized by Charles II and his court and, on his return to Britain in 1660, puppeteers among his entourage introduced Polichinelle to Britain. Formerly Pulcinella, a puppet version of one of the zanni, or buffoons, in the Italian Commedia dell’ Arte, the French version in Britain soon became Punchinello, subsequently shortened to Punch. When Samuel Pepys noted this character’s first recorded appearance in England, in Covent Garden in 1662, the puppet is believed to have been a marionette.

Muffin the Mule, a popular early television puppet.

Although we have no specific details of the puppets themselves, George Speaight1, cites convincing evidence in support of the view that these were indeed marionettes. The size of the booth erected for a performance before Charles II at Whitehall Palace was of such dimensions that it is inconceivable that it was intended for glove puppets. There are references to puppets that ‘fly through clouds’ and perform other feats that are most naturally accomplished by marionettes, and allusions to political ‘wire-pulling’ also associated with marionettes. According to Speaight, the popularity of glove puppets in the first half of the seventeenth century was surpassed in the second half by the attractions of the marionette performances and the widespread popularity of Punch among all levels of society – John Milton, for example, certainly frequented the puppet theatre: he attributed the inspiration for Paradise Lost, which first appeared in 1667, to a puppet version of the story of Adam and Eve.

In early eighteenth-century England, puppetry was a fashionable entertainment, the puppet show being one of the places at which to be ‘seen’, and many of the continental aristocracy had their own private puppet theatres. In France, the live actors felt so threatened by the popularity of the marionette operas that in 1720 a special parliament was called to consider demands to have the puppet performances restricted, but it found in favour of the puppeteers.

In 1738 we find the first record in the USA of an English-style marionette show, The Adventures of Harlequin and Scaramouche by a puppeteer named Holt. The USA also provides evidence that, in some cultures, the marionette might have developed from the mask. Among the north-west coast Native Americans, for example, there was the use of masks which then acquired articulated jaws. Next they were held in the hands rather than worn on the head and later were suspended on strings.

As Kapellmeister at the Eisenstadt palace of Prince Esterhazy between 1761 and 1790, Haydn composed the music for five marionette operettas, and Philemon and Baucis was composed for a marionette performance for the Empress Maria Theresa. Gluck, too, composed marionette operas to entertain patrons such as Queen Marie Antoinette and later as Kapellmeister to Maria Theresa. Haydn and Goethe both acknowledged the influence of puppet theatre in their formative years. Goethe was presented with a puppet theatre at six years of age, for which he subsequently wrote many plays; this is said to have given him inspiration many years later for Faust, which also became a significant work for puppet theatre.

In the second half of the eighteenth century, Mozart composed works such as Don Giovanni, Die Fledermaus, Il Seraglio and Die Zauberflote which, though not written for puppet theatre, have become classics of puppet theatre, especially at the renowned Salzburg Marionette Theatre.

In Britain interest in puppetry was flagging in the later part of the eighteenth century, but the Italian fantoccini arrived on the scene and raised the popularity of marionettes with performances full of tricks and transformations, a tradition that survives to this day.

By 1820 the puppeteers in England were catering for children and the popularity of the marionettes had given way to Mr Punch, now presented as a glove puppet. The permanent puppet theatres closed and the marionettes, like the glove puppets, took first to the streets and then to the pleasure gardens. The travelling marionette companies now took up the melodramas of the live theatre as well as presenting the old tricks and transformations in pantomime-style shows. Another rise in fortune occurred towards the end of the nineteenth century, when England’s marionette troupes were considered to be the best in the world. These companies toured the globe with wagons carrying large theatres for elaborate productions.

During the twentieth century the marionette has flourished once again despite the arrival of the cinema and television. Indeed, marionettes were there from the start of television, broadcasting from a tiny studio in which Baird was experimenting and using the BBC’s wavelengths at midnight after they had closed down. When television developed, there was Muffin the Mule and a range of children’s programmes featuring marionettes, leading to the later supermarionation programmes such as Supercar, Captain Scarlet and Thunderbirds, which now have a cult following.

Live performances and productions with marionettes have displayed developments of even greater artistry. Over the past century there have emerged crafts men and women who produce fabulous designs, execute the construction with great skill and present wonderful performances for adult audiences as well as those for children. These include solo marionette performers, small groups and major companies.

There has also been a significant expansion of permanent marionette theatres in Britain, America, throughout much of Europe to the Far East and Australia, some preserving traditional styles and others extending the possibilities of the art, a long-standing tradition in popular culture with a special attraction for performers and their audiences.

A fantoccini-style Victorian marionette, believed to be Joey the Clown, based on the famous Joey Grimaldi. In the Hogarth Collection at the Puppet Centre.

1. Speaight, G., Punch & Judy, A History (Studio Vista, 1970).

2 MARIONETTE DESIGN

PRINCIPLES OF MARIONETTE DESIGN

In order to understand and design marionettes, one should appreciate something of the nature of puppet theatre in general and marionettes in particular. They are not actors in miniature and generally they fail as puppets if they are made too lifelike for that is to misunderstand what it is about puppets that has captivated human audiences for thousands of years.

Characters from Aesop’s Fables (left) and The Tempest (above), carved by Gren Middleton, costumes by Juliet Rogers, Movingstage Marionettes. The heads, hands and feet are carved in limewood and the bodies and limbs of the larger characters are carved from jelutong. Smaller figures are limewood throughout. The wood is finished with stains or left plain, rather than painted.

An actor acts but a puppet is. The marionette is sometimes referred to as the complete mask, the mask from which the human actor has withdrawn. It was this that appealed to Edward Gordon Craig when he proposed the Uber-marionette and George Bernard Shaw argued the case for a puppet theatre to be attached to every drama school to teach the quality of ‘not acting’.

Fiery Jack by Paul Doran, Shadowstring Theatre.

All puppets, including marionettes, need to be an essence and an emphasis of whatever they represent, whether human, animal, or an abstract concept. They hint at or suggest qualities, movements or emotions and they are most effective when they interpret rather than copy the human form. The power of the puppet resides in large part in the fact that it is a simplification of form; it invites the audience to participate in a rather special way – to supplement those dimensions of character and movement that are merely suggested by the puppet through its design and by skilful manipulation.

A marionette built to human proportions tends to look too long and thin, so it is usual to exaggerate the head, hands and feet slightly. Finely detailed modelling or carving will be lost to an audience more than a few feet away, so keep the modelling bold. When designing or creating the head, think of the modelling and painting as akin to stage make-up compared with everyday cosmetics. Despite the ways in which the puppet departs from human proportion, it is useful for characterization to study books on human anatomy for artists, and basic ‘how to draw’ books of the human form.

With puppets, one is liberated to create characters that can defy natural laws; they can fly through the air, turn inside out and transform in all manner of ways. Their design is not limited by the human form, for one creates not only the costumes of the actors, but also their heads, faces, body shapes, and so on. Of course, the puppet needs to look like, and move as, the intended character and this is conveyed in part by the shape, size and modelling of every part of the puppet. The way in which it moves is influenced by its structure, the method of control and the skill of the manipulator. So it is important to be clear about what the marionette is to be and to do, and to design it accordingly.

Marionettes can be as simple or as complex as you wish but their apparent complexity and remoteness from their operator distinguish them from other forms of puppet. Unlike a hand or rod-puppet, which you position just where you want it, the marionette, which is controlled via strings, has more independence of movement so it has even more of a life of its own. Therefore a marionette with good balance, appropriate distribution of weight and suitable joints will have intrinsic movement that assists the manipulator. When one operates a well-constructed puppet, the puppet does a good deal of the work but it can also resist intended gestures or other movements, so flexibility or restriction of movement is an important consideration.

Prospero and Ariel: carved by Gren Middleton, costume by Juliet Rogers, Movingstage Marionettes. Ariel was created in glass by a professional glass blower to designs by Gren Middleton; the use of glass was inspired by the stage direction ‘Enter Ariel invisible’.

Materials should be selected with a view to both the joints required and the relative weight of the different parts. If the pelvis is too light in relation to the legs, for example, the puppet will not walk well. In fact, any part that is too light will not facilitate good control and movement. Marionettes that are entirely carved achieve a unity of design and good distribution of weight that promotes a quality of movement other puppets do not always achieve.

It is always a good idea to plan the puppet, drawing it to actual size both from the front and in profile. You may find that drawing on lightly squared paper eases the transition from the plan to the puppet. If so, work with fair-sized squares of around 2.5cm (1in) so that the figure is divided into manageable segments. When drawing your design, have regard for the notes on proportion and structure that follow.

MARIONETTE PROPORTION

Marionettes can be any size or shape and the variations of proportion can contribute significantly to characterization, so effectively there are no rules. However, some guidance may be useful in order to achieve relative proportions within a puppet.

A guide to proportions for a marionette.

A puppet’s head is approximately a fifth of its height, or just a little less. As with humans, the hand measures the same as from the chin to the middle of the forehead and covers most of the face. The hand is also about the same length as the forearm and the upper arm. Feet are a little longer, approximately equal to the height of the head. Elbows are level with the waist, the wrist with the bottom of the body, and the fingertips half-way down the thigh. The body is usually a little shorter than the legs.

Typical proportions for a head: the ears align with the eyes and nose, and the eyes are approximately one eye’s width apart.

The way in which the face is framed by the addition of hair can have a strong influence on the puppet’s appearance, and the age of a character affects the proportions of the head. As a general guide, the face has three approximately equal divisions: chin to nose; nose to eyebrows; eyebrows to brow-line. The bulk of the hair will often add to the height of the head and can make the proportions appear somewhat different. When designing the head, do not make the profile too flat, particularly the back of the head.

Eyes are a little above the mid-point between the chin and the top of the skull and are usually one eye’s width apart, depending on the width of the nose. The top and bottom of the ears normally align with the top and bottom of the nose. The mouth is a little above the mid-point between the chin and the nose, and the corners of the mouth align with the centre of the eyes. The neck is set a little way back from the centre of the skull and, for characterization, may be slightly angled by the positioning of joints between the head, neck and body.

The angle at which the head sits in relation to the body contributes significantly to characterization.

Common mistakes are to make the eyes too high or too close together and foreheads too low. Ears are sometimes too high or too small and need to be examined from all angles as they also contribute to characterization.

Consider proportion not only in terms of height but also in terms of the bulk of the body and limbs. Ensure that the neck, arms and legs have sufficient bulk; if they are too thin this will affect the way the costume hangs and moves and the lack of bulk will often become apparent. Check the profile of the entire puppet; if you hold the puppet in a strong beam of light, does it cast a strong, interesting shadow?

MARIONETTE STRUCTURE

Generally, a marionette head moves most effectively if the neck is separate from both the head and the body, though the head and neck may be made in one piece. I made most of my early marionettes with head and neck as a single unit and was perfectly satisfied with the result. However, when I later made them separately, I discovered the greater variety of movement that I could achieve. For some purposes the neck may be made as part of the body and joined inside the head.

Three types of neck. Top: the neck made as part of the head. Middle: the neck made as part of the body and joined inside the head. Bottom: a separate neck joined inside both the head and the body.

A marionette body is normally jointed at the waist but movement may be restricted as necessary. Some puppet makers favour a three-part body with the upper body and pelvis separated by a large ball around which they move, which can be most effective. Some applications will require a one-piece body with no waist joint, though this sometimes affects the way the puppet walks.

For unity of design and weight, hands and feet are best constructed in the same material as the head. When different materials are used, ensure that the finished appearance has a coherence of style and texture.

Wrist joints are usually designed to allow a good deal of flexibility but ankle joints tend to be more restricted to ensure a good walking action.

Where necessary, puppet parts may be weighted with sheet lead (available from builders’ merchants) or lead curtain weights, glued or nailed on. Puppet parts cast in rubber may be weighted by pouring a little liquid plaster into the hollow part.

Examples of carved marionettes.

A marionette carved by the late John Wright for the Puppet Centre collection. The wooden ball at the waist facilitates smooth movement.

A marionette carved by a student on a course tutored by John Roberts, PuppetCraft. Working from carefully drawn full-size patterns, this large puppet (about 28in tall) has been carved from lime and softer jelutong woods.

ANIMAL MARIONETTES

Most quadrupeds have the same basic structure (see illustration, page 18). The animal parts are made from the same materials described for human puppets but size and weight may be factors in selecting the material and construction method to be used. Legs are usually carved or constructed with laminated layers of plywood. If necessary, additional shaping can be achieved with a modelling material, or by padding to shape with foam rubber if the leg is to be covered with fabric. Feet are carved or made from the same material as the head.

The structure for most quadrupeds follows the same principles as the dog illustrated. Although the legs will normally be jointed, a leg carved as one piece is very effective for this particular puppet, carved by John Thirtle for the Puppet Centre’s demonstration collection.

ROD-MARIONETTES

A rod-marionette is a very old style of puppet operated from above, usually by a mixture of rods and strings. The traditional Sicilian puppets, which perform tales of Orlando Furioso, stand some 1m (3ft) high, are carved throughout in wood, and have brass armour (see illustration on page 8). The puppets have the same basic structure as other marionettes but the style of control and method of manipulation are very different.

A rod-marionette by the late Barry Smith. The head and body are supported by a single central rod while the hands are controlled by strings.

Another type of rod-marionette, sometimes called a ‘body puppet’ is found in southern India. This puppet is suspended on strings hung from the puppeteer’s head and rods are used to manipulate the puppet’s hands. Such a figure might have a flowing robe rather than legs and feet but, if it does have feet, they may be attached to the puppeteer’s shoes.

A rod-marionette or body puppet by John Blundall. This technique, which is common in southern India, has strings from the puppeteer’s head and neck to the puppet’s head and shoulders, and rods to the hands.

3 HEADS – MATERIALS AND METHODS

Before embarking upon creating a head, refer to the information on marionette design in Chapter 2 and plan the head in relation to the whole puppet. Is the neck to be separate from the head or created with the head as a single unit? At what angle should the head sit in relation to the neck and shoulders? Does the puppet need a moving mouth or moving eyes? How will its personal characteristics and its age influence the design?

The Pied Piper by John Roberts, PuppetCraft. Head and hands are carved in limewood and finished without paint and with glass-bead eyes.

A modelled head with moving eyes created by the author.

There are three basic methods for creating heads; these are carving, modelling and casting (or moulding). Traditionally, marionettes were mostly carved in wood and this remains a popular method though it requires more skill than modelling or casting. Older puppetry texts often refer to the use of plastic wood and Celastic for modelling and casting. However, the formulation of plastic wood has been changed and it no longer has suitable properties for modelling, and Celastic, an impregnated woven material used with a solvent, is no longer available. The following pages outline a variety of materials that are suitable for each construction method, including some long-standing methods and the latest materials available.

You will discover a personal preference for particular techniques, so do experiment and always be on the lookout for new materials that appear in craft shops, decorating and DIY outlets, or in theatrical chandlers/suppliers. In theatrical suppliers in particular you will find all manner of materials and hardware of use for puppet construction and finishing, staging and scenery, including many of the modelling and casting materials described in this chapter.

TOOLS

The beginner could probably manage with the basic tools that one might find in a household toolbox, unless one is to carve puppets in wood. However, a slightly enhanced selection of tools, detailed below, is desirable, and there may be occasions when you add to the collection for a particular purpose – brazing equipment, for example, may be needed for some types of metal work. Keep all tools clean and well maintained, sharp where appropriate, and use them only for their intended purpose.

A vice with wooden jaws is essential for making most types of puppet and their controls. This may be permanently attached to a workbench or the type that can be clamped to any suitable surface.

You will certainly need a few craft knives and a variety of scissors. You will maintain the sharpness of your scissors by keeping each pair for particular materials and not using your fabric scissors for cutting paper or cardboard. A tenon saw, coping saw and a junior hacksaw cover most other cutting, though you will need a hand saw for easier cutting of large blocks of wood.

A power drill is useful, though delicate drilling is best done with a hand drill and occasionally you might need a carpenter’s brace. The brace will need augers for drilling larger holes while the other drills need a variety of twist drills, spade drills (or points) up to 5mm (¼in) diameter, and a countersink bit. It is also useful to have an awl, a bradawl and a gimlet.

Shaping and smoothing is facilitated with rasps, files and various grades of glasspaper. Flat and round Surform rasps and a small hand tool are particularly helpful. Chisels with different width blades, mainly flat back and the odd bevelled back, will be needed for general-purpose work, together with a mallet. Carving tools are detailed in the following section.

You also need: screwdrivers, for example ratchet, Phillips and Pozidriv, stub and electrician’s; large and small pliers, pincers, wire cutters and tin snips; claw, Warrington and tack hammers; a selection of brushes; measuring implements and a try square.

CARVING A HEAD

Woodcarving Tools

A woodworking vice fixed to a rigid bench is essential to hold the wood firmly and safely while carving. A powered band saw, tenon saw and coping saw are useful for cutting basic shapes. Rasps are also handy. While proper woodcarving rasps are recommended, even a Surform rasp can be helpful for general shaping. Some woods can also be shaped considerably with glasspaper.

The main stages in carving a head.

The outline shapes are drawn on the block of wood.

The major waste is removed with a saw and chisel.

The face is shaped with chisels and sanded before shaping the back of the head.

From my early days in puppetry I always admired the carving style of (the now late) John Wright from the Little Angel Theatre in London, and followed closely his recommendations, though with nothing like the same degree of skill. He recommended for the beginner a basic set of tools consisting of a 16mm (⅗in) and a 25mm (1in) flat chisel, a 6mm (¼in) fishtail flat, a 6mm (¼in) deep gouge and a 13mm (½in) shallow gouge plus a woodcarving mallet and a pair of callipers for comparing measurements. A sharpening stone and oil are also essential to maintain the tools in good condition and minimize the risk of accidents caused by using blunt tools.

Woods to Use

Well-seasoned limewood, a close-grained hardwood, is recommended for carving a marionette head. It is easily worked, does not tend to splinter too readily and it is fairly light in weight. However, you might need to find a specialist timber merchant to obtain it. A second choice would be American white wood. Jelutong is suitable for large puppet parts and simple head shapes but it is not recommended for thin or delicate parts.

When selecting the wood, avoid pieces with cracks, stains or knots and look for a straight grain. Remember that the head is much deeper than it is wide, so allow sufficient wood for the front to back dimension, though you can join two pieces with woodworking adhesive if necessary.

Carving Technique

The beginner will find it helpful to practise on spare pieces of the type of wood to be used before attempting to carve the actual puppet. It is also a good idea to carve the simpler parts first, so start with the body, then the limbs, next the feet and hands, and finally carve the head.

Plan to use the wood with the grain running vertically down through the whole puppet, except the feet, which the grain will run along. Draw the outline shapes on to the blocks in thick pencil. As the wood is cut away these outlines will be lost; when this happens, lightly sand the wood to study progress and redraw the outlines as necessary.

River Girl and Poet, carved by Gren Middleton, costumes by Juliet Rogers, Movingstage Marionettes, for a commissioned piece, River Girl by Wendy Cope.

Some people screw a block of wood securely to the bottom of the head in order to hold it in the vice for carving and then remove it when the carving is complete. Others carve the ears last, leaving them as blocks for securing in the vice, as described below.

Secure the rear of the block firmly in a vice and carve the face and front half of the head, back almost to the ears. First, cut away any major waste with a saw and a chisel or rasp. Then embark upon the carving proper with chisels. Make the chisel cuts in the same direction as the grain or the wood will split and more than intended will be cut away, ruining the head. For larger cuts, hold the chisel and tap it firmly and sharply, but not too heavily, with the mallet. For fine paring, rest the end of the chisel in the palm of one hand, against the heel, and place the other hand over the shaft and blade, helping to guide it. Always keep both hands behind the direction of the cutting edge. Take care to shape the head fully: a common mistake is to leave the head too angular, reflecting the shape of the block from which it has been carved.

Next, sand the face smooth, first with coarse glasspaper on rough parts, working down in stages to a very fine one. When the face is complete, work towards the back of the head and finally shape the ears, which must be done with care.

If the neck is separate from the head, hollow out the socket for the neck and through this hole cut away as much of the head as possible to reduce its weight.

MODELLING A HEAD

General Principles

Modelling is a very flexible method for creating heads. Starting with either a base shape or a model in Plasticine (plastilene), you can build the required shape in the chosen material and work on the head until you achieve the desired result. Some materials are fairly flexible, which allows you to cut back or sand the head when dry. Most modelling materials are strong and reasonably lightweight when used in an appropriate thickness.

A modelling stand.

Modelling on a Plasticine base.

The Plasticine model with cardboard or thin plywood ears.

The Plasticine is coated with a release agent and covered with a modelling material.

When dry, the head is cut open and the Plasticine removed.

Modelling on Plasticine

Make a modelling stand by screwing together a substantial dowel and a block of wood. Ensure the base is sufficiently large not to topple over, as the Plasticine model will be quite heavy. Model the basic head shape around the dowel. Alternatives to Plasticine may be used but select one that remains pliable or it may be difficult to remove from the head at a later stage. (If the puppet is to have moving eyes seepages 35–6 for details of how to prepare this stage of the model.)

Avoid fine detail at this stage, as this will disappear as the modelling progresses. In fact, with some materials, hollows will become significantly shallower as layers are added, so make the modelling bolder than you wish the final shape to be.

Removing the Plasticine from a modelled head.

Cut open the head with a suitable tool: always cut away from the hand holding the head.