20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

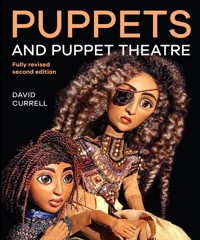

Puppets & Puppet Theatre is essential reading for everyone interested in making and performing with puppets. It concentrates on designing, making and performing with the main types of puppet, and is extensively illustrated in full colour throughout.Topics covered include: nature and heritage of puppet theatre; the anatomy of a puppet, its design and structure; materials and methods for sculpting, modelling and casting; step-by-step instructions for making glove, hand, rod and shadow puppets & marionettes; puppet control and manipulation; staging principles, stage and scenery design; principles of sound & lighting and finally, organisation of a show.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 308

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

PUPPETS AND PUPPET THEATRE

David Currell

First published in 1999 by The Crowood Press Ltd Ramsbury, Marlborough Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2014

© David Currell 1999

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 790 8

To Emily Ayşa and Alexander Emre, my children, who love puppet theatre.

Photo Credits

Courtesy John M. Blundall, Puppet Theatre Consultant, The Scottish Mask and Puppet Theatre Centre, Glasgow: 35, 136 (a)(b)(c)(d)(e)(f), 169 (a)(b)(c); courtesy Coomber Electronic Equipment Ltd, Worcester: 196 (a)(b)(c); courtesy Ray & Joan DaSilva, DaSilva Puppet Company, Bicester, Oxfordshire: 165 (b), 202, 206; courtesy Mary Edwards, The Puppet Factory Ltd., Far Forest, Worcestershire: 4, 42, 43; Steve Finch, courtesy Puppet Centre Trust, London (Hogarth Collection) and Salford Museum & Art Gallery: 38; Steve Finch, courtesy Puppet Centre Trust, London (on loan to touring exhibition, courtesy Jim Henson Productions) and Salford Museum & Art Gallery: 6; Chris Lawrenson, courtesy Lyndie Wright, Little Angel Theatre, London: 182, 203; Philippe Mangen, courtesy Puppet Centre Trust, London (on loan to touring exhibition, courtesy John Blundall, Scottish Mask & Puppet Theatre Centre): 10, 39; courtesy Puppet Centre Trust, London (Crafts Council Collection): 36; courtesy Puppet Centre Trust, London (Jessica Souhami Archive): 128 (b); courtesy Ian Purves, International Purves Puppets, Biggar, Lanarkshire, Scotland: 195 (a)(b); John Roberts, courtesy Lyndie Wright, Little Angel Theatre, London: 99; David Rose, author’s collection: 5, 9, 32, 37, 52, 59, 79, 110 (b)(c)(d), 138 (a)(b), 140 (e), 153 (c)(d)(e), 190 (a), 117, 118, 119, 120, 130, 133, 186, 188, 189; David Rose, courtesy Puppet Centre Trust, London: 16, 19 (a)(b), 69; David Rose, courtesy Puppet Centre Trust, London (Barry Smith Collection): 7, 21, 22, 27, 33, 53, 58; David Rose, courtesy Puppet Centre Trust, London (Crafts Council Collection): 15; David Rose, courtesy Puppet Centre Trust, London (Hogarth Collection): 1, 2, 3, 17, 103; courtesy Albrecht Roser, Stuttgart, Germany: 198; Stephen Sharples, courtesy Christopher Leith, London: 128 (a); Stephen Sharples, courtesy Lyndie Wright, Little Angel Theatre, London: 44; Barry Smith, author’s photograph collection: 26, 165 (a), 201; Barry Smith, courtesy Puppet Centre Trust, London (Barry Smith Collection): 11, 13, 68, 171, 172; David Stanfield, courtesy Lyndie Wright, Little Angel Theatre, London: 8, 46, 61, 62, 65, 102, 200; courtesy Strand Lighting Ltd., Middlesex: 187 (a)(b)(c)(d), 192, 194 (a)(b); courtesy Lyndie Wright, Little Angel Theatre, London: 47, 123, 124, 191, 199, 205; courtesy Zero 88 Lighting Ltd., Cwmbran, Gwent: 193.

Contents

1 An Introduction to Puppet Theatre

Puppet Theatre Heritage

The Nature of the Puppet

Types of Puppet and Staging

Using This Book

2 The Anatomy of a Puppet

Principles of Design

Proportion and Design

Puppet Structure

Glove Puppets

Hand Puppets

Rod Puppets

Animal Rod Puppets

Bunraku-Style Rod Puppets

Hand-Rod Puppets

Rod-Hand Puppets

Rod-Glove Puppets

Rod-Marionettes

Marionettes

Animal Marionettes

3 Heads – Materials and Methods

Tools

Exploring Materials

Sculpting

General Principles

Foam Rubber

Polystyrene

Expanding Foam Filler

Wood

Modelling

General Principles

Paste and Paper

Paper Pulp

Plaster and Muslin

Milliput (Epoxy Putty)

Fibreglass

Casting

General Principles

Making a Plaster Cast

Casting a Rigid Head

Casting a Latex-Rubber Head

Painting and Finishing Head, Hands and Feet

Principles for Painting the Face

Materials and Methods

Hair

4 Construction Techniques

Heads

Necks and Neck Joints

Eyes

Moving Mouths

Bodies for Glove and Hand Puppets

Rod Puppet Shoulder Blocks

Bodies for Rod Puppets and Marionettes

Waist Joints

Arms, Elbows and Shoulder Joints

Hands and Wrist Joints

Legs and Knee Joints

Hip Joints

Feet and Ankle Joints

Costume

5 Control and Manipulation

Glove and Hand Puppets

Rod Puppet Controls

Rod Puppet Manipulation

Marionette Controls

Marionette Manipulation

6 The Shadow Puppet

Principles

Construction

Simple Shadow Puppets

Articulated Shadow Puppets

Decoration and Colour

Three-Dimensional Puppets

Tricks and Transformations

Full-Colour Puppets in the Traditional Style

Control

Principles

Methods of Fixing Main Controls

Controlling Moving Heads and Mouths

Arm Controls

Leg Control

7 Staging Techniques

Staging Principles

General Staging Structures

Simple Staging: A Table-Top Theatre

Flexible Staging Units

Stages and Scenery for Glove, Hand and Rod Puppets

An Open Booth

A Proscenium Booth

Accessories

Scenery

Stages and Scenery for Marionettes

Staging

Accessories for Marionette Stages

Scenery

Staging for Mixed Puppet Productions

Curtains and Backcloths

Drapes for the Stage

Proscenium Curtains

Backcloths and Back-Screens

Staging for Shadow Puppets

Stage Construction

The Screen

Scenery

8 Lighting and Sound

Lighting the Puppet Theatre

Different Types of Lighting

Lighting for Glove and Rod Puppets

Lighting for Marionettes

Lighting for Shadow Puppets

Lighting Control

Colour Lighting

Organizing the Lighting

Lighting Equipment

Black Light Technique

Sound

Principles

Microphones

Sound Systems

9 The Performance

Essential Considerations

Variety Shows

Plays

Principles for Adapting a Story

The Scenario and Script

Design and Construction

Music for the Show

Voice Work and Recording Technique

Manipulation and Movement

Rehearsal

The Performance

Useful Addresses

Index

Acknowledgements

Puppeteers world-wide are generous in sharing their knowledge, skills and experience, and I have been extremely fortunate to benefit from this generosity in the preparation of Puppets and Puppet Theatre.

For information on their approaches to puppet making and performing, as well as for photographs, I am indebted to John Blundall, Ray DaSilva, Mary Edwards, Geoff Felix, Christopher Leith, Ian Purves and Lyndie Wright. Technical information on lighting and sound has been received from Sue Davies and Bill Richards of Strand Lighting Limited, Claire House of Zero 88 Lighting Limited, and Mark Piatkowski of Coomber Electronic Equipment Limited. Others who have contributed photographs are listed separately.

My very sincere thanks are due to David Rose, a friend, colleague, and photographer, who has been extremely generous with his time and expertise, and has made it possible to include so many colourful and informative photographs.

I am grateful also to Loretta Howells (Director), Allyson Kirk and Glen Alexander of the Puppet Centre Trust, London, who have provided reference resources, technical information and photographs, and made available the Trust’s extensive collections for photography.

The late Barry Smith, Director of the Theatre of Puppets and Ray DaSilva, Co-Director of the DaSilva Puppet Company, shared their individual approaches to puppet performance for a previous book, which is embedded also in the present work. I therefore acknowledge with gratitude the major contributions made to the performance chapter by each of these puppet masters.

Finally, I am extremely grateful to the team at The Crowood Press, who have been enthusiastic and supportive, and helped to make the book a pleasure to write.

A marionette carved by John Wright, The Little Angel Theatre, London

1 An Introduction to Puppet Theatre

PUPPET THEATRE HERITAGE

Puppetry and puppet theatre have a long and fascinating heritage. The origins of this visual and dramatic art are thought to lie mainly in the East, although exactly when or where it originated is not known. It may have been practised in India 4000 years ago: impersonation was forbidden by religious taboo and the leading player in Sanskrit plays is termed sutradhara (‘the holder of strings’), so it is likely that puppets existed before human actors.

Fig 1 Javanese wayang golek rod puppets

In China, marionettes were in use by the eighth century AD and shadow puppets date back well over 1000 years. The Burmese puppet theatre had a significant influence on the development of the human dance drama, and a dancer’s skill is still judged on his or her ability to re-create the movements of a marionette. And Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653-1725), Japan’s finest dramatist, wrote not for human theatre, but for the Bunraku puppets (see Fig 24), which once overshadowed the Kabuki in popularity.

Fig 2 An Indian marionette from the Rajasthan region

Fig 3 A traditional carved Burmese marionette

In Europe, the puppet drama flourished in the early Mediterranean civilizations and under Roman rule. The Greeks may have used puppets as early as 800 BC, and puppet theatre was a common entertainment – probably with marionettes and glove puppets – in Greece and Rome by 400 BC, according to the writings of the time. In the Middle Ages, puppets were widely used to enact the scriptures until they were banned by the Council of Trent. Since the Renaissance, puppetry in Europe has continued as an unbroken tradition.

Sicilian puppets – knights one metre (three feet) high, wearing beaten armour and operated from above with rods (see Fig 32) – have performed the story of Orlando Furioso since the sixteenth century, but this type of puppet was, in fact, in use as long ago as Roman times. In Germany, puppets have performed The History of Doctor Faustus since 1587, and in France marionette operas became so popular that in 1720 the live opera attempted to have them restricted by law. The eighteenth-century French Ombres Chinoises shadow puppets were not only a fairground entertainment but were popular among artists and in the fashionable world.

In England, puppets were certainly known by the fourteenth century and, during the Civil War, when theatres were closed, puppet theatre enjoyed a period of unsurpassed popularity. By the early eighteenth century it was a fashionable entertainment for the wealthy, and in the late nineteenth century England’s marionette troupes, considered to be the best in the world, toured the globe with their elaborate productions.

The ubiquitous Mr Punch originated in Italy. A puppet version of Pulcinella, a buffoon in the Italian Commedia dell’ Arte, was carried throughout Europe by the wandering showmen and a similar character – including Petruschka (Russia), Pickle Herring, later Jan Klaasen (Holland), and Polichinelle (France) – became established in many countries. The French version was introduced to England in 1660 with the return of Charles II; it became Punchinello, soon shortened to Punch, and enjoyed such popularity that he began to be included in all manner of plays. By 1825, Punch was at the height of his popularity, and the story in which he played had taken on its standard basic form.

In the nineteenth century the puppet show was taken to America by emigrants from many European countries, and their various national traditions laid the foundations for the great variety of styles found there today.

Eastern Europe had early traditions of travelling puppet-showmen but, with a few exceptions, puppetry did not develop significantly there until the twentieth century. However, it then progressed at an impressive rate.

The twentieth century has brought new materials and techniques to puppet theatre, and has seen a revival of interest in the art through television and film, as well as a renewed emphasis on the quality of live performances. Official recognition of puppetry as a performance art has now been achieved.

THE NATURE OF THE PUPPET

The survival of puppet theatre over some 4000 years owes a great deal to man’s fascination with the inanimate object animated in a dramatic manner, and to the very special way in which puppet theatre involves its audience. Through the merest hint or suggestion in a movement – perhaps just a tilt of the head – the spectator is invited to invest the puppet with emotion and movement, and to see it ‘breathe’.

A puppet is not an actor, and puppet theatre is not human theatre in miniature. In many ways, puppet theatre has more in common with dance and mime than with acting. Puppet theatre depends more upon action and less upon the spoken word than the actor does; generally, it cannot handle complex soul-searching, and it is denied many of the aspects of non-verbal communication that are available to the actor. But the puppet, still or moving, can be just as powerful as the actor.

The actor represents but the puppet is. The puppet brings to the performance just what you want and no more; it has no identity outside its performance, and brings no other associations on to the stage. The puppet is free from many human physical limitations and can speak the unspeakable, and deal with taboos. The power and potential of the puppet has attracted artists such as Molière, Cocteau, Klee, Shaw, Mozart, Gordon Craig, Goethe and Lorca who have all taken a serious interest in this art – one of the most liberating forms of theatre.

Fig 4 Pulcinella, a large marionette, as he first appeared in England, re-created for television by Mary Edwards. The head is carved in jelutong wood

TYPES OF PUPPET AND STAGING

Most types of puppet in use today fall into four broad categories – hand or glove puppets, rod puppets, marionettes and shadow puppets – but there is a variety of combinations. Among these are glove-rod, hand-rod, rod-hand and rod-marionette puppets, detailed in Chapter 2. There is also a wide range of other related techniques, from masks to finger puppets, from the toy theatre to animated puppet film.

The glove puppet is used like a glove on the operator’s hand; the term ‘hand puppet’ is sometimes used synonymously but here it describes figures where the whole hand is inserted into the puppet’s head. Glove puppets are quite simple in structure but hand puppets often have a costumed human hand, or arms and hands operated by rods. These puppets, although limited in gesture to the movement of one’s hand, are ideal for quick, robust action and can be most expressive. The live hand inside the puppet gives it a unique flexibility of physique.

The rod puppet is held and moved by rods, usually from below but sometimes from above; those in the Japanese Bunraku style require two or three operators, who hold the puppet in front of them. Rod puppets vary in complexity, ranging from a simple shape supported on a single stick to a fully articulated figure. They offer potential for creativity in design and presentation, and their range of swift and subtle movements enables them to deliver anything from sketches to large dramatic pieces.

The marionette is a puppet on strings, suspended from a control held by the puppeteer. It is versatile and can be simple or complex in both construction and control. Performances can be graceful and charming, and fast and forceful action is generally avoided. For manipulation, the experienced puppeteer draws upon the marionette’s natural movements to great advantage.

Shadow puppets are normally flat cut-out figures held against a translucent, illuminated screen. The term is also used loosely to describe fullcolour, translucent figures operated in the same manner. Shadow puppets are ideally suited to the illustration of a narrated story, but they can also handle direct dialogue and vigorous knockabout action.

Increasingly, puppeteers are exploring the use of space instead of restricting themselves to the confines of the conventional booth or stage. However, glove and rod puppets are usually presented from within a booth. The traditional covered booth is still used for ‘Punch and Judy’, but an open booth without a proscenium has become popular for other shows; it affords far greater scope for performance, and a wider viewing angle.

Marionette variety acts are frequently presented on an open stage with the puppeteer in view. The large marionette stage with a proscenium to hide the operators tends to be used for plays in more permanent situations: size, portability and setting-up time are factors that have influenced the trend towards open-stage performances. Although shadow puppets are generally limited to performing against a translucent screen, a great deal of ingenuity has been displayed by performers in their use of multiple screens, projections, superimposed images and the like.

Fig 5 A Chinese style of glove puppet

Fig 6 Oscar the Grouch, a hand puppet designed and made by Don Sahlin for Sesame Street. It is made of foam, covered in fleece and synthetic fur fabric

Fig 7 Joseph, from the Nativity, a carved wooden rod puppet of unknown origin

Fig 8 Aunt Rebecca, designed and carved by John Wright for A Trumpet for Nap, the Little Angel Theatre

Fig 9 Chinese shadow puppets created in leather, which is treated to make it translucent and coloured with dyes

It is possible to combine or alternate the use of different types of puppet in one performance. Used with other puppets, shadow play can illustrate linking narrative, portray distant action and, for example, dream, memory and underwater sequences. However, the staging demands of some puppet combinations can be considerable.

USING THIS BOOK

This book covers fundamental principles of puppet anatomy and design, extensive details of puppet construction and every aspect of the performance, including staging, lighting and sound.

Many aspects of the design and construction of the puppet are interdependent. For example, decisions about the performance will affect the type of puppet and staging methods to be used, and a head cannot be made for a rod puppet or marionette until it has been decided how the neck is to be joined to the body or whether the neck is to be created separate from, or integral to, the head. It is important, therefore, to design and make the puppet according to the advice given in all of the chapters; try to resist the temptation to launch into making a puppet with little idea of what the puppet will be required to do. Time spent reading and planning will be a worthwhile investment.

2 The Anatomy of a Puppet

PRINCIPLES OF DESIGN

The puppet is both an essence and an emphasis of the character it is intended to reflect. The puppet artist has to create and interpret character, not imitate it, so the puppeteer’s art involves simplification and selection, and offers freedom not only to design the costumes of the actors, but also to create their heads, faces, body shapes, and so on.

You need to create a puppet that looks and moves like the character you wish to convey. Plan a project, however simply, and know what the puppet is to be and do, then you can design a specific puppet for that purpose. (Remember, it may be necessary to explore different techniques as the puppet progresses.)

Often beginners make puppets by drawing upon what they think they know about people: they make children small, adults bigger, and try to convey all the character in the face. The result is puppets that are less than convincing. You must conceive the design as a whole, and for this you need to observe and analyse what you see. Like an artist, study natural form and interpret it by searching for the underlying structures and working on these. Look to the basic structure, and see how it gets its form.

Fig 10 The Devil as Herdsman from Stravinsky’s The Soldier’s Tale, the Little Angel Theatre. Designed and made by Lyndie Wright using polystyrene covered with pearl glue and brown paper; string is used to edge the sculpting. The hands were made on a wire armature using celastic, which is no longer suitable for puppets; leather would be used instead now

In principle, keep your designs bold and simple, with clean lines, to achieve greater dramatic effect; delicate features, however beautiful, will be lost on the puppet stage. A puppet that lacks bold design may appear nondescript from only a few feet away, while too much facial detail may hinder the conveying of character. Also note the importance of the eyes; they bring the face to life perhaps more than any other single feature.

Fig 11 Anonymous, a hand puppet with a cast head designed and made by Barry Smith for his Theatre of Puppets’ production, A Variety of People. Now in the Puppet Centre Barry Smith Collection

It is useful to keep a scrapbook for inspiration and ideas: include drawings, pictures of people of all ages and types, in uniform or costume, features, cartoons, and articles, for example, on make-up or hair styles.

PROPORTION AND DESIGN

Strict adherence to the ‘rules’ of proportion does not make an interesting and effective puppet, while a puppet made to human proportions looks unnatural. However, it is worth considering certain guidelines with regard to proportion.

The adult human head is approximately one-seventh of a person’s height; for a puppet, it is often about one-fifth, but could be any size you choose. On humans and puppets, the hand is approximately the same size as the distance from the chin to the middle of the forehead, and covers most of the face. The hand is also the same length as the forearm and as the upper arm; feet are a little longer. Elbows are level with the waist, the wrist with the bottom of the body and the fingertips half-way down the thigh. The body is generally a little shorter than the legs.

Pay attention also to the bulk of the body and the limbs. A common mistake is to make the puppet too tall and thin, lacking any real body shape, particularly in profile. Hold the puppet between a strong light and a blank wall and examine the shadows it casts: strongly designed puppets will create strong, interesting shadows. Ensure that the neck, arms and legs have sufficient bulk in relation to the head and body. Even when covered with clothes, it is noticeable if limbs are too skinny.

The head can be divided into four approximately equal parts – the chin to the nose; the nose to the eyes; the eyes to the hairline; and the hairline to the top of the skull, which is slightly less than the other sections. The eyes are approximately half-way between the chin and the top of the skull. The top and bottom of the ears are normally in line with the top and bottom of the nose.

Avoid putting the eyes too high in the head or too close together, the forehead too low, and the ears too high or too small for the head. Ears should be studied from the side and from behind: they contribute to characterization more than might be imagined. Viewed in profile, the neck is not in the centre of the head but set further back and possibly angled, depending on character.

However, it is the variations from the norm which are usually most significant in creating a dramatically effective character. For example, the spacing of the eyes depends upon the width of the nose and the characterization required. The age of a character affects the proportions of the head. ‘Hair’ can completely change the head’s apparent shape, so consider the bulking of your chosen hair material when shaping the skull; different materials, such as thick synthetic fur or dyed string, will have varying influences upon size, shape and, therefore, character.

Fig 12 The setting of the head on the neck has a significant influence on characterization

The angle at which the head sits on the body and the way in which it moves are essential to characterization, so it is important to consider these points with regard to the positioning of joints between the head, neck and body.

PUPPET STRUCTURE

Glove Puppets

Glove puppets are constrained in size and design by the need to contain a human hand. The operator’s wrist becomes the puppet’s waist, so it is important to have a long ‘glove’ almost to the elbow, so that your arm does not show while performing. Use a dark material to help it recede, or a neutral colour, if that blends in more effectively.

The neck is usually slightly bell-bottomed, to assist in securing the glove body. The recommended method of operation is with index and middle fingers in the neck, thumb in one arm, and ring and little fingers in the other.

Fig 13 (a) Typical proportions for a puppet

Fig 13 (b) suitable proportions for the head – top of ears aligns with eyes; bottom of ears aligns with nose; the eyes are approximately one eye’s width apart

The puppet’s hands may be made as part of the glove, separately in fabric, or sculpted, modelled or moulded, with a hollow wrist or cuff; its arms are attached securely to the cuff and the puppeteer’s fingers are inserted to control the hands. This allows more character in the shape of the hands but more practice may be needed to achieve expressive gesture and to handle props effectively.

Fig 14 (a) The basic glove puppet

Fig 14 (b) A modelled hand with a hollow wrist

Glove puppets may be given legs. Carve, mould or model the foot and lower leg, and use a fabric thigh. Such legs usually swing freely; you can control them directly with the fingers of your free hand inserted into holes in the back of the thighs, but this limits you to operating only one puppet at a time.

Fig 15 Glove puppets may be given legs and feet, as with this Punch character cast in fibreglass by Geoff Felix for the Puppet Centre Collection. The mould was smashed to release the undercut rigid head. A plug with a twofinger space was cast to fit the neck for effective control

Fig 16 Spotty Dog, an animal glove puppet in which the body effectively sits on the back of the operator’s hand and wrist. Made from foam rubber, felt and fur fabric by Anna Braybrooke (now Anna Poland) for Polka Children’s Theatre

For animal characters, make a simple glove with an animal head, covering the glove with a human costume, synthetic fur fabric, or other suitable material. Alternatively, a complete animal body that rests on the wrist and forearm may be made of cloth and stitched to the glove.

Hand Puppets

The term ‘hand puppet’ is used here to describe a puppet in which the operator’s whole hand is inserted into the head. It usually has a moving mouth, operated with the thumb in the lower jaw. It may be a simple sleeve of material with a head attached, sometimes called a ‘sleeve puppet’, which is suitable both for human and animal characters. A stuffed body and dangling legs may be attached to the sleeve.

Two-handed puppets are made in the same way, leaving underneath a hole large enough to insert crossed arms; such a body is often stiffened by a buckram or foam-rubber lining.

If the hand puppet needs to maintain a rigid body shape, it may be made on a framework of strong card or wire netting (chicken wire), which is padded and covered.

A hand puppet may have a disproportionately large head and a very dominant mouth, hence its other name, ‘mouth puppet’. One hand effects head, mouth and body movements. The puppeteer’s other arm and hand are costumed. Alternatively, an additional operator may provide the puppet’s hands. Puppet hands usually have only three fingers – two of the operator’s fingers are fitted into one of the puppet’s – and this tends to look quite natural on the puppet.

Fig 17 The crocodile from Punch and Judy is a form of ‘sleeve puppet’ with snappy wooden jaws padded with foam rubber and a long sleeve of fabric for the body

Hand puppets tend to be large, so the head should be made of a light material, such as foam rubber or polystyrene, covered with fabric or synthetic fur fabric. The head is made with a separate lower jaw joined by a strong fabric hinge.

Fig 18 A two-handed hand puppet

Make the body suitably full for the character. The whole puppet may be created in foam rubber, the head and a limb from blocks, and the body from sheet foam rubber.

Fig 19(a) A form of hand puppet, sometimes called a ‘mouth puppet’, with a gloved human hand. Created by Kumquats, Germany; available from the Puppet Centre;

Fig 19 (b) another view of the Kumquats puppet, showing the method of operation; black sleeves normally worn by the operator have been omitted for clarity

Rod Puppets

The body is designed to be supported by a central rod that is free to turn, but may be fixed if desired. Even a head and a robe with no body or limbs can be effective, and the natural movement of the fabric contributes to this. A rod puppet frequently has a head, shoulder block, arms, hands and robes, but no body or legs, as it is usually visible only to waist or hip level. If it has no body, appropriate padding under the costume assists characterization.

A short central rod gives more scope for movement, as the operator’s wrist becomes the puppet’s waist, but a long rod enables the puppet to be held much higher.

It is a simple matter to attach the head to the central rod to permit it to turn and look up and down. If it is only to turn, the head may be constructed with the neck attached, then secured on the central rod. The rod turns inside the shoulder block/body. If the head is to move vertically, construct it without a neck but with an elongated hole in its base; it pivots on the top of the central rod that forms the neck. A pull-string or a piece of stiff wire is then used to control vertical movement. The rod is also able to turn inside the shoulder block or body.

Fig 20 (a) A basic rod puppet with a shoulder block but no body or legs. The long rod enables it to be held high, but limits body movement;

Fig 20 (b) a short central rod limits the height of the puppet, but permits considerable scope for movement;

Fig 20 (c) for nodding, the head has an elongated hole in the base and pivots on the central rod

In each case, a supporting ‘collar’ is attached to the rod under the shoulder block or inside the body; this holds it in place on the rod, but permits turning.

Hand movement is effected by thin but stiff metal rods. If the puppet has legs, they usually swing loose; often, an additional puppeteer is needed if they are to be manipulated.

A rod puppet with a body and legs, plus robes and controls can be a considerable weight, so design the puppet and select construction materials and costume fabrics accordingly. The larger the puppet, the more important it is to use a material such as polystyrene rather than wood.

Fig 21 A rod puppet with legs: Lorenzo by Barry Smith for Theatre of Puppets’ production of Keats’ Isabella (or The Pot of Basil)

Animal Rod Puppets

Animal puppets can be made from a wide variety of materials. Two common techniques are to build a head and body by one of the regular methods of modelling, moulding or sculpting, or to create a body around a central core of rope, spring, flexible tubing, and so on.

Fig 22 A rod puppet cat with a flexible body and moving eyes

Fig 23 For an animal rod puppet, a rod to the body provides the main support while an additional rod controls head movements

The head and body may be created as a single unit without a joint, but normally the head moves separately from the body, controlled by an extra rod directly to the head or inserted through the body. The supporting rod for the body is attached at a point suitable for good balance.

The legs may be made from jointed wood, laminated plywood shapes, or in a variety of creative ways (if the puppet is given legs at all).

Bunraku-Style Rod Puppets

The term Bunraku refers to a Japanese style of performance that is a blend of the arts of puppet theatre, narration and samisen music. The head of a true Bunraku puppet is carved and hollowed, sometimes with a range of moving features. It is mounted on a head-grip, which fits into a wooden shoulder board with padded ends.

Two strips of material hang from the shoulders at the front and back; to the bottom of these is attached a bamboo hoop or a piece of wood for the hips. The limbs are carved, often with shaped and stuffed fabric upper parts; strings from the arms and legs are tied to the shoulder board. The padded costume creates the real body shape and character.

Fig 24 A Bunraku performance

Fig 25 The structure of a Bunraku puppet

The chief operator inserts his left hand through a slit in the back of the costume and holds the head-grip to control head and body. With his right hand he moves the right arm. A toggle, pivoted in the arm and with strings attached, is used to effect hand movements. A second operator uses his right hand to move the puppet’s left arm by means of a rod about 38cm (15in) long joined to the arm near the elbow. The hand is moved by two strings attached to a small crossbar on the rod; the operator uses his index and middle fingers hooked around these strings. The legs are moved by a third operator using inverted L-shaped metal rods fixed just above the heel.

Fig 26 Pierrot: the main operator supports the body and controls the head with a short central rod, also operating the left arm through a long rod with a toggle control to effect hand movements. A second operator controls the right arm, and a third operator controls the legs and feet

This technique has been adapted to a range of practices with one, two or three-person operation. The neck is often angled somewhat and the basic head-grip is made from a rod or a strong strip of plywood. If plywood is used, one end is built into the neck, and the other end is made into a pistolgrip handle by gluing on shaped pieces of wood.

Fig 27 Pierrot form Pierrot in Five Masks by Barry Smith’s Theatre of Puppets. The puppet is operated in Bunraku style by three people. Different latexrubber masks fit on to a covered polystyrene head shape

The hand is attached to the arm with or without a flexible wrist joint. A control rod, operated from behind, is inserted into the heel of the hand or the arm at the elbow or wrist, as appropriate. The hand-control rod (which may be weighted if required) can act as a partial counterbalance to the arm, so that it does not hang lifeless by the puppet’s side while it is not being operated. Toggle hand controls may be added.

Fig 28 An angled neck attached to a pistol-grip control

Hand-Rod Puppets

This is a cross between a hand puppet and a rod puppet, usually with a moving mouth. The operator’s hand is inserted for head, mouth and body movements; the hands and arms are controlled by rods.

Fig 29 A hand-rod puppet of the type used for many Muppet characters

Rod-Hand Puppets

This type of puppet requires one or two operators. At its simplest it has a central rod and a robe, but no body; usually it has at least shoulders to help establish body shape. The puppeteer holds the rod in one hand and uses the other hand, costumed, as the puppet’s hand, or slips a gloved hand through a slit in the puppet’s robe; the slit may be elasticated if desired. Alternatively, one puppeteer operates head and body and another provides the costumed hands and arms.

Fig 30 A rod-hand puppet with a short central rod and shoulder block, but with gloved human hands

Rod-Glove Puppets

This puppet retains the directness and potential of the glove puppet yet has the stature and proportions of the rod puppet. The head is secured to a central rod but it has a glove-style body, to which are attached separate hands with tubular arms. The puppeteer moves the arms and hands with thumb and index finger, and holds the rod with the other fingers. The costume is attached to a small shoulder block that sits on a supporting collar.

Fig 31 A rod-glove puppet has a smaller shoulder block sitting on the supporting collar

Rod-Marionettes

The term rod-marionette refers to various types of puppet operated from above, like marionettes, either by rods and strings, or just by rods. The traditional Sicilian puppets, carved in wood with beaten brass armour, are operated in this way by strong metal rods to the head and the sword arm, and a cord to the shield arm. Twisting the head-rod from side to side creates sufficient momentum to make the legs swing.

Fig 32 A Sicilian rod-marionette used to perform many episodes of the story of Orlando Furioso

Fig 33 The Sicilian style of rod-marionette has been adapted for this character which has a modelled head: Ubu, from Ubu Roi, performed by Barry Smith’s Theatre of Puppets

The same style is used for the puppet in Fig 33 while the animal in Fig 34 has head- and body-’rods’, through which total control is effected. When the puppet is standing upright, its momentum and the gentle swaying of its body causes its hind legs to walk; when on all fours, walking is achieved by alternately lifting front and rear rods with slight forward pressure. To reduce the weight, the rods may be constructed from aluminium tube; the