23,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

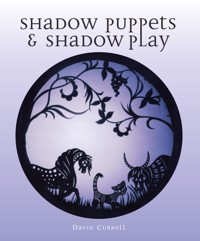

Shadow Puppets and Shadow Play is a comprehensive guide to the design, construction and manipulation and presentation of shadow puppets, considered by many to be the oldest puppet theatre tradition. Traditional shadow play techniques, together with modern materials and methods and recent explorations into theatre of shadows, are explained with precision and clarity, and illustrated by photographs that include the work of some of the finest shadow players in the world. Topics covered include an introduction to shadow play, its traditions and the principles of shadow puppet design; advice on materials and methods for constructing and controlling traditional shadow puppets and scenery; step-by-step instructions for adding detail and decoration and creating transculent figures in full-colour; detailed methods for constructing shadow theatres using a wide range of lighting techniques; techniques of shadow puppet performance and contemporary explorations with shadow play; and instructions for making animated, silhouette films with digital photography. Lavishly illustrated throughout, Shadow Puppets and Shadow Play sets out detailed instructions for making and presenting shadow puppets by traditional methods and with the latest materials and techniques. Superbly illustrated with 420 colour photographs and helpful tips and suggestions.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

SHADOW PUPPETS

& SHADOW PLAY

David Currell

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2007 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2015

This impression 2014

© David Currell 2007

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 062 1

Frontispiece: The Turkish Karagöz.

PHOTO CREDITS

Photos of Bradshaw’s Shadows/Richard Bradshaw: Richard Bradshaw, except pages 183: John Delacour; 142: Brenda Sarno; 31, 33, 52, 180: Michael Snelling; 182: Margaret Williams; all courtesy Richard Bradshaw. Photos of Caricature Theatre/Jane Phillips: David Currell, except page 177, courtesy of Jane Phillips. Photos of Compagnie Amoros et Augustin, La Citrouille, Jean Pierre Lescot, Jessica Souhami, Teatro Gioco Vita, Théâtre-en-Ciel: Puppet Trust Archive Collection. Photo page 161: Coomber Electronic Equipment Ltd. Photos of the DaSilva Puppet Company: David Currell, courtesy Jane Phillips, except pages 9: Ray DaSilva; 178: Joe Harper, courtesy Ray and Joan DaSilva. Photos of Figure of Speech/Jonathan Hayter: David Currell except pages: 15, 162, 166, 170, 179, 181: Martin Hayward-Harris; 78, 79, 103, 186: Stephen Holman; all courtesy Jonathan Hayter. Photos of Christopher Leith’s Shadow Show: Christopher Leith. Photos of Lotte Reiniger’s work from the author’s collection: courtesy (the late) Lotte Reiniger, except pages 42: David Currell; 42: David Rose; 31, 191: from the DaSilva collection, courtesy Ray and Joan DaSilva. Photos pages 136 and 157: Roscolab Ltd. Photo of Salzburg Marionette Theatre: Gretl Aicher. Photos of Shadowstring Theatre/Paul Doran: David Currell, courtesy Paul Doran. Photo page 25: Eugenios Spatharis. Photos pages 152, 153, 159, 160: Strand Lighting Ltd. Photos pages 8, 18, 20, 96, 97, 132: David Currell, courtesy Jane Phillips. Photos pages 7, 19, 22, 23, 122: David Currell, courtesy Puppet Trust. Photos pages 12, 21, 26, 27, 28, 29: DaSilva Collection, courtesy Ray and Joan DaSilva. All other photos: David Currell, except pages: 95: David Rose; 41: (the late) Barry Smith; all from author’s collection

TO EMILY AND EMRE CURRELL

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In my previous books for Crowood, I acknowledged the generosity of fellow puppeteers for their hospitality and the sharing of information about their construction methods and presentation techniques. This is no less true of the present book for which a number of highly regarded makers and performers have given me access to their shadow figures, their collections and their personal archives.

I have been privileged to have had such cooperation from performers whose work I admire. Richard Bradshaw, Ray and Joan DaSilva, Paul Doran, Jonathan Hayter, Christopher Leith and Jane Phillips share a long and distinguished history of directing shadow play as well as other forms of puppet theatre. All have made major contributions both directly in preparing the book and indirectly through their work over many years. Other major influences represented here whose past work has inspired me are Jessica Souhami, who now works in other fields, and the late Lotte Reiniger, the silhouette film-maker whose work is heralded as a landmark in the history of the cinema and animated film. To all these individuals my sincere thanks are offered.

I am grateful also for information and support from Penny Francis, MBE, a tireless advocate for puppet theatre, the Puppet Centre Trust, London, colleagues in the Design and Technology Centre at Roehampton University, and theatrical lighting firms DHA/Rosco Ltd. and Strand Lighting Ltd. Additional assistance with photography has been received from Marcus Barbor, Emily Currell, Emre Currell and Jodika Patel.

CONTENTS

1

Shadows and Shadow Puppets

2

Shadow Play Traditions

3

Shadow Puppet Design

4

Shadow Puppet Construction

5

Detail, Decoration and Transformation

6

Shadow Puppet Control

7

Staging

8

Scenery

9

Lighting and Sound

10

Contemporary Explorations

11

The Performance

12

Silhouette Films

Useful Addresses and Contacts

Index

1 SHADOWS AND SHADOW PUPPETS

SHADOWS

A shadow is an image cast by an object intercepting or impeding light or the comparative darkness formed when such an object causes a difference in intensity of light on any surface. A shadow, however, does not have a separate existence but depends for its existence, its nature and its form upon the source of light that creates it and the surface upon which it is cast.

A figure from the DaSilva Puppet Company’s production of Kipling’s The Cat That Walked by Himself.

Your inseparable companion, you cannot touch your shadow nor feel it; it may be on the ground in front of you but you cannot jump over it; turn around and suddenly it is behind you; you cannot shake it off nor outrun it. Sometimes it is long and thin, sometimes shorter and fatter; sometimes it is dark and crisp, at other times faint and hazy. Shadows can appear elegant, lively, playful or grotesque, mysterious and sinister. The shadow has given inspiration to many writers, among them Edgar Allan Poe (Shadows), Hans Christian Andersen (The Shadow), Oscar Wilde (The Fisherman and His Soul) and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, whose fascination with the phenomenon of coloured shadows informed his Theory of Colour and whose literary works used the shadow as a strong image.

Shadows have often been regarded as having magical qualities and have strong cultural, religious and scientific dimensions. Our distant ancestors had shadows from the sun during the day and from their fires at night. Their cave paintings indicate the significance of the shadow even then – this intangible, mysterious figure that undergoes transformations in its appearance and has no substance yet is visible for all to see. How were they to regard it? Was it associated with life or with death? Did it belong to this world or the next?

The shadow has been viewed at times as a disembodied spirit, a phantom or one’s double and the shadow was how the ancient Egyptians envisaged the soul. Greek and Roman literature makes many references to the shadow as the soul after death and the shades was how they referred to hell, or Hades. In folklore only the dead, the dying or ghosts have no shadow and the Bible abounds with references to the shadow both as protective (for instance, ‘under the shadow of thy wings’) and as the shadow of death. Even today in Indonesia, where the shadow puppets represent ancestral spirits, gods and demons, the dalang, or puppeteer, still performs a semi-priestly function.

Cinderella by Lotte Reiniger.

Pliny (Natural History, xxxv 15) cites Egyptian and Greek myths suggesting that tracing around the outline of a person’s shadow was a precursor to painting and (in Natural History, xxxv 43) he recounts a myth that links the shadow to the origins of sculpture. It tells of a potter’s daughter who wanted to preserve the image of her lover who was travelling abroad, and so, on a wall by lamplight, she traced around the shadow of his head. The potter, Butades, used this outline to create a clay image in relief and then fired it; thus sculpture was said to have begun. Later Athenagoras draws upon the same myth to explain the origins of doll-making.

Although occasionally referred to as the poor relation of reflection, the shadow has long been a significant element in pictorial art and photography. Leonardo da Vinci identified the link between the shadow and the perception of space and many artists have suggested that the shadow is as significant as the real object, while the Surrealists use the shadow as an independent motif. In photography and film too, light and shade are essential structural elements. This is particularly evident in some of the renowned films produced around 1920 (Dr Caligari’s Cabinet, Nosferatu, The Shadow), where shadows are used to hugely expressive effect.

The shadow is deeply imbedded in science too. As well as being used as a monitor of time, it was the shadow of the Earth on the surface of the moon that led Aristotle to deduce that the Earth is spherical and larger than the moon. The changing length of shadows led to the deduction that the Earth’s axis is inclined and shadows were again used to calculate its circumference and the height of the pyramids.

The shadow of a Javanese wayang kulit puppet exhibited at Shadowstring Theatre.

These examples highlight how perceptions of the shadow have intrigued us and become woven into faiths, literature and the fabric of daily lives, providing a metaphor for human existence:

For in and out, above, about, below, Life’s nothing but a Magic Shadow-show, Played in a Box whose Candle is the Sun, Round which we Phantom Figures come and go.

Edward FitzGerald (1859), translation from the twelfth-century poem, The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

A Javanese wayang kulit shadow puppet.

THE SHADOW PUPPET

A broad definition of a traditional shadow puppet would be a two-dimensional figure held against a translucent screen and lit so that an audience on the opposite side of the screen can see the shadows thus created. However, as will be apparent in the following chapters, this has become a rather limited definition in relation to the wide spectrum of shadow theatre today.

Traditionally made of parchment or hide, shadow puppets are now usually made of strong card, thin plywood, acetate, occasionally wire or sheet metal, but there is scope for experimentation with all manner of materials. They need not be difficult to make and can look surprisingly delicate and intricate on the screen.

A shadow puppet cut in thin plywood by Steve and Chris Clarke (Wychwood Puppets) for Shadowstring Theatre.

When we think of shadows we tend to envisage solid black images, but shadow play often incorporates translucent figures that cast coloured shadows. The colourful, translucent, traditional Chinese ‘shadow’ puppets fall into this category and similar figures made with modern materials are commonly used to create colourful images. Some performers use card from which shapes have been cut to project ‘white shadows’ and flexible, reflective surfaces are illuminated with powerful lamps to bounce light images on to shadow screens.

Matsu, a figure cut in metal from lighting gobo material by DHA-Rosco for Paper Tiger, by the DaSilva Puppet Company.

An owl created in X-ray film by Paul Doran for a Shadowstring production of Witch Is Which.

Figures created with galvanized wire.

Translucent figures created by Jessica Souhami from white card, coloured and oiled.

One should also distinguish shadows from silhouettes. The silhouette takes its name from the Marquis Etienne de Silhouette (1709–67) who was Controller-General in France in 1759. His severe measures to deal with the French economy gave rise to anything mean or cheap being referred to as à la silhouette. At this time black, cut-out portraits became immensely popular, particularly with the Marquis. They were so much cheaper than miniature oil paintings that they became widely known as ‘silhouettes’ and part of the standard French vocabulary, a term later to be adopted more widely.

A print of an eighteenth-century silhouette chair.

A silhouette, unlike a shadow, exists in its own right and cannot be distorted; it is an image, usually in solid black, set against a light background. So we refer to something silhouetted, not shadowed, against the light. Though not a shadow, this is a closely related phenomenon that produces similarly powerful images that can be more dramatic visually than the object itself. Olive Blackham, in Shadow Puppets (Barrie & Rockliff, 1960), noted this impact by highlighting the difference between the puppet placed flat on the table and the shadow it casts on the screen, suggesting that ‘the strength and impact of the solid shadow is quite different from that of the object’.

In most performances the shadow puppet itself is never seen. What the audience sees is the shadow that emerges from a unique combination of the puppet’s shape, the light and the screen, and for which all of these elements are essential.

The shadow-player, like a painter, is creating a picture on a surface, a picture that is then transformed by the imagination of the spectator. All puppets present an essence and an emphasis of the characters or concepts they represent and invite the audience to supply dimensions that the puppet can only hint at. In so doing, they involve the audience in a special way. This is even more true of shadow theatre where the spectator not only interprets the flat images, but also draws upon experience and imagination to give them volume and depth.

In other forms of live performance the actors inhabit three-dimensional space and are in direct contact with the audience. By contrast, shadow puppets usually have an indirect relationship with their audience, separated by a screen that filters, and sometimes modifies, the image that the audience sees.

Shadow play may present familiar objects in unfamiliar ways. It can explore an object from many angles, from a distance, in close-up, circle around it, view it from above, view it internally, show it sectioned, see right through it, or depict different views consecutively or even simultaneously. In this sense it has much in common with film. As with film, we can accelerate or slow down a process with shadow play. We can watch a flower grow and bloom or we can pause or reverse the process.

Some shadow-play traditions, such as the Nang in Thailand, use a static figure carved within a setting. The carving is highly suggestive of movement and this, combined with the motion of the performer who holds it aloft and the flickering live light that illuminates it, creates a sensation of movement in the shadows it creates.

Gilgamesh by Teatro Gioco Vita, Italy.

Théâtre-en-Ciel, France, play with scale and show the figure sectioned with internal images.

Sunjata by Compagnie Amoros et Augustin, France.

Shadow puppets are sometimes used in conjunction with three-dimensional puppets to accompany narrated links or underwater sequences, distant action, the passage of time or as a mirror with the three-dimensional puppet in front and the shadow (or full-colour image) as the reflection. The shadow screen is aptly termed ‘the cloth of dreams’ in the Arab world and shadow play is particularly effective for dream sequences and memories with floating images that come in and out of focus, disappear, reappear and overlap, capturing the strange quality of this facet of human experience.

The eastern form of shadow theatre was introduced to Europe between the seventeenth and the eighteenth century but, despite occasional flourishes of activity, it was not firmly established in its own right until the middle of the twentieth century, and even then it was very much the poor relation when compared with three-dimensional figures. It is sometimes suggested that the reason for this resides in the different cultural and spiritual mindset between east and west, that shadow play has a transcendental quality in keeping with Asian spirituality, whereas the western audience has been more comfortable with the rationality of tangible, three-dimensional representations.

Shadow figures used as a background to marionettes in Eine Kleine Nachtmusik by the Salzburg Marionette Theatre.

In recent years, however, shadow play in Europe has undergone a revolution. The traditional performance for centuries used the rectangular screen. Even when live light gave way to electric it was comparatively basic illumination so, for clear definition, the figures had to be held tight against the screen. The figures themselves tended to be naturalistic and were used mainly to illustrate a story.

A major breakthrough came as the result of experiments in the 1960s into the physical laws ruling shadows and the appearance of the halogen lamp. Rudolf Stössel in Switzerland explored the effects of a range of materials and equipment including lenses, mirrors, prisms, foils and liquids, as well as projectors and halogen lamps. His work had a strong influence on the work of many avant-garde European companies, among them the Compagnie Amoros et Augustin in France and the Teatro Gioco Vita in Italy, who, in the 1970s, experimented further with halogen lighting and opened up a host of possibilities.

This liberated the figures which no longer needed to be held tight against the screen. The relative distances between the figure, the screen and the light could be altered to change the size of the images which could fill a whole wall if required. They no longer needed a flat, rectangular screen: all manner of geometric shapes were now possible and screens could be movable. One company performed in a tent, using the whole tent as a projection surface. Rollers, castors, ropes and pulleys came into play so that screens, their shapes and their orientation could be changed during the performance. Companies explored shape, pattern, tone, line, texture and form. They experimented with the relationship between figure, screen, lighting, space and the human body, and generated new conceptions of shadow theatre.

Massive projections superimposed on figures close to the screen in Gilgamesh by Teatro Gioco Vita, Italy.

The number of companies that perform exclusively with shadows or include shadow theatre productions in their repertoire has increased significantly in the past thirty years and shadow theatre is once again undergoing exploration by artists and giving rise to work of quality and originality.

‘Screaming Angel’, one of a series of astral images from Moontime by Jonathan Hayter, Figure of Speech; the image is constructed with a collage of tissues, paint and varnish on vacforming PVC.

2 SHADOW PLAY TRADITIONS

ORIGINS

Some authorities deem shadow play to be the oldest form of puppet theatre. Stories regarding the origin of shadow puppets vary considerably, but they often contain common elements of death, grief or remorse, preserving through the shadow show the presence of the absent person, echoing Pliny’s account of the origins of sculpture. A Chinese myth dating from 121BC tells of an emperor overcome with grief when his favourite mistress died. All attempts to ease his sorrow failed until one of the artists of the court created a shadow figure likeness of her and, after much rehearsal to capture her gestures and voice accurately, presented his shadow show with the figure illuminated behind a silk screen. The emperor was comforted and the shadow show was born.

A traditional Chinese shadow puppet made from hide.

Similarly the traditional Turkish shadow show is said to be based on real characters and features Karagöz and Hacivat, workmen engaged in building a mosque (some say a palace) in the city of Bursa during the Ottoman period. Their frequent quarrels were so amusing that other workers stopped to listen and the work was not progressing. The sultan eventually lost patience and had the quarrelsome pair executed. Later he was filled with remorse so a member of his court arranged for leather, cut-out representations of Karagöz and Hacivat to be created, to be used in shadow plays of their entertaining exploits, a tradition that survives to this day.

There is no scholarly evidence to substantiate these accounts nor others like them and some writers even suggest that string puppets appeared before shadow theatre. We also cannot be sure to what extent it was an art carried from one area to another by migration, by occupation of territory, by traders, or whether in some areas it developed quite independently.

The similarities between the design of the traditional Javanese shadow figures and tomb representations of the Egyptian pharaohs from 3,000 years ago have tempted some to conjecture whether this might be the origin of the Javanese wayang kulit shadow puppets. Others draw parallels between the wayang kulit and the Indian tolubommalata puppet tradition. Although the figures themselves are quite different, scholars argue that the techniques, the repertoire, the style, conventions and rituals associated with a Javanese performance have too much similarity for India to be discounted as their origin. Certain Indonesian authorities, by contrast, hold that the shadow play techniques are of purely Indonesian origin although the themes were imported much later.

Many literary references to shadow play throughout the ages provide confirmation of its existence and lead us to believe that it was well established at the time and place that the text was written. However, they offer no further clue to its origin and, except for comparatively recent texts, little or no insight into the content of the performance, if performance is an appropriate term. An example is to be found in what is believed to be the first written reference to shadow play, Plato’s Republic, chapter VII, ‘The Allegory of the Cave’, written around 366BC. It mentions figures, a fire, performing magicians, a curtain in front of the performers, an audience, and speaking and moving shadows, but nothing to support the notion of theatre, as opposed to a shadow parade. Most authorities, however, would agree that shadow play originated in the east where the ancient traditions still survive, often closely associated with religious festivals and held in higher esteem than anywhere else in the world.

INDIA

Indian shadow figures vary greatly from region to region and different styles may be performed by different castes. Three examples of Indian shadow play are described, exemplifying both their common elements and the wide variation in the style of the puppets.

Among the most beautiful are the large, colourful tolubommalata puppets from the Andhra Pradesh region in south-east India. The puppets may be as much as 120 to 150cm high (48–60in) and are made from ‘non-violent’ hide, which means the animal died naturally. Most figures would be made from buffalo hide, though for noble figures such as a god or a king deerskin would be preferred. The hide is scraped and treated until it is stiff, strong and translucent and then coloured with dyes. Heads are generally depicted in profile and are sometimes interchangeable. The main control for a figure is a vertical, split cane with an additional cane to each hand. The legs, which are jointed at the knees, swing freely.

Traditionally, the large white screen consists of two saris extended one above the other and pinned together along the centre with date palm thorns. It can be anything up to 2m (6ft) high and 6m (20ft) wide. It is held by at least three poles, one to the top and one to each side, and often by a fourth pole along the bottom of the screen, which is about knee-high to ensure good visibility for the audience. Once the only source of light was an oil lamp suspended behind and above the screen; this added charm and life to the shadows, now often created with electric lighting.

An Indian shadow puppet.

In keeping with other eastern traditions and the common theme of the struggle between good and evil that runs through these stories, the figures are divided on each side of the screen with noble, virtuous characters to the right and evil characters to the left, as viewed from backstage.

A performance often begins mid-evening and continues throughout the night, the puppets performing to an accompaniment of songs and narration. Music is a significant element of a performance and is provided by a harmonium, drums and cymbals. The performers stand behind the screen to operate the puppets; they wear ankle bells and provide both rhythm and sound effects by stamping their feet on two wooden planks placed one on top of the other. Male and female performers speak for male and female figures; in the past, only men operated the puppets but now women are involved in the manipulation too. The performances have religious significance as well as being entertainment: they are often given in temple grounds as part of a temple festival and may be intended to appease the rain gods and to promote the welfare of the animals. Frequently the performance will open with a religious ritual such as a prayer of supplication to Lord Ganapathi. The stories are based upon the Hindu epic poems, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, interspersed with local gossip and topical commentary that provide light relief.

Ramayana means ‘life of Rama’ and favourite stories tell of Rama’s marriage to Sita, their banishment to the forest with his brother Laksmana, Sita’s abduction by the monster king Rahwana and her rescue with the help of the monkey king Hanuman, after numerous battles. The Mahabharata deals with the conflict between two branches of a family descended from the supreme gods of Hinduism. One branch usurps the throne from the rightful heirs, causing a dispute that can be resolved only by war that involves several generations of the family. It is finally settled with a victory for justice and the concept of right. Everyone knows the stories well, so, during the performance, members of the audience may come and go, eat their meals and so on. At some point the performer makes a collection and, if anyone refuses to contribute, he is ridiculed by a comic puppet character that utters obscenities and makes vulgar gestures at him. Oral tradition dates the tolubommalata back to at least 200BC and there is some documentary evidence that may be interpreted as indicating shadow play somewhat earlier than this.

A marked contrast to the tolubommalata puppets is to be found on the east coast of India north of Andhra Pradesh in Orissa. Here shadow play is known as ravanachhaya (the shadow of Ravana) and the performers are traditionally descendants of musicians and officials of the local royal court. There are similar themes, taken from the Ramayana, and similar musical accompaniment, but the figures are small, unjointed and perform with simple movements. Deerskin is used for divine characters while other figures are made from sheepskin or the hide of mountain goats; the hide is not scraped so thoroughly as that of the tolubommalata puppets and so it is thicker and opaque. The puppets have quite a detailed outline and expressive poses but they have little internal, cut-out ornamentation.

In the Kerala region on the south-western coast, shadow play is known as tolpavakuthu and similarly tells stories taken from the life of Rama. It has some features in common with the style in Orissa, including musical accompaniment with percussion instruments, but the performances are generally given by scholars or poets who recite both prose and verse in a stylized fashion. Rituals feature in the performances, often performed in temple grounds as part of religious festivals. The puppets are traditionally made entirely of opaque deerskin and range from approximately 50 to 80cm high (20–30in). Despite the modest size of the puppets, the shadow screen may be anything up to 12m (39ft) wide, with some 130 figures operated by at least five puppeteers.

Indian shadow figures.

INDONESIA

Puppet theatre in Indonesia, particularly in Java and Bali, is an important part of the culture and no type is more so than the wayang kulit shadow puppets. Wayang kulit has a number of forms each of which draws upon a distinct repertoire, but the best known is wayang purwa which takes its themes from the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. It is so much a part of Javanese life that even shop signs and business logos feature major shadow characters. The term wayang is a general one referring to the theatrical performance and is said by some to refer to the concept that all art is a shadow of life; it is qualified further by terms that define the type of puppet, kulit being hide and purwa meaning ancient.

The shadow puppets are the most common of all the wayang figures and it is widely held that all forms of Javanese theatre originated from the shadow play. The puppets are about 60cm (24in) high and usually made from buffalo hide treated to produce parchment. The process involves the removal of excess oils, sun-drying, smoothing, soaking, stretching, drying, scraping, rubbing and polishing. When the parchment is ready, the separate parts are cut out and the delicate, filigree-type pattern is chiselled into each. The eye is the last feature to be cut since it is believed that this is when the puppet’s life begins.

A Javanese wayang kulit shadow puppet.

The process of carving the skin and the design of the figures is set down by tradition and is related to the character portrayed. As soon as a puppet enters, its appearance conveys to the audience its rank, its character and, in fact, almost all they need to know about it. In addition to the profile shape, the decorative headdress and other adornments, information is conveyed by the eyes, by the angle of the head and even the distance between the feet. Virtuous, noble characters will have refined features, almond-shaped eyes and graceful bodily shapes with the head tilted slightly forwards, while crude characters will have larger bodies, round eyes, bulbous noses, pointed teeth and feet set wide apart in a fighting stance.

The figures are generally opaque when decorated; despite being used for shadow play, they are painted and gilded in a highly ornate fashion since the audience may watch not only their shadows but the actual figures behind the screen. At one time women were restricted to watching only the shadows while men were permitted to watch both the shadows and the actual puppets, which include representations of gods, demons and ancestral spirits.

Facial colouring varies with an individual’s character and a number of versions of a figure may be used with different colourings during a performance to indicate changes to its character or personality over time. Black is associated with virtue and wisdom, white with youth and beauty, gold also suggests beauty (or sometimes is simply used as decoration without any connotation), blue denotes cowardice and red suggests aggression and untrustworthiness.

Three control rods are used, traditionally made of horn with the main vertical rod shaped to follow the line of the puppet’s design and tapered to a point at the base. The arms are jointed at the shoulder and elbow and the hands are attached to controls, but the legs are carved as part of the main figure and not jointed.

Unlike the Indian figures that may be operated by a group of standing or dancing performers, wayang kulit performances have a single puppeteer, the dalang, who sits behind his screen to manipulate the puppets, providing narration, speaking all the dialogue, conducting the gamelan orchestra that sits behind him, and sometimes singing too. He sits and performs from dusk to sunrise without a break and, between the toes of his right foot, holds the kechrek, a kind of rattle or mallet which he strikes repeatedly against a wooden box in which the puppets are stored when not being used. A system of signals indicates his intentions to the orchestra almost imperceptibly.

The differences in wayang kulit designs are highly significant, indicating both rank and personality; the hide is treated to become parchment, which, unlike leather, is translucent unless it is painted or gilded.

Lotte Reiniger’s scraperboard impression of a wayang kulit performance, with the gamelan orchestra sitting behind the dalang, who performs with an oil lamp suspended above him.

The role of a dalang has been likened to that of a priest; not only is he a regular feature of festive and ceremonial occasions, births and marriages, but, as the puppets are considered to be the incarnation of ancestral spirits, the dalang acts as a medium between the spirits and his audience. Clearly, whoever becomes a dalang must have an array of personal qualities far beyond that of entertainer and he is thus a highly respected artist.

The screen, or kelir, is approximately 1.5m high and 4.5m wide (5ft×15ft). Made of cotton, it is supported by bamboo sticks with the base at, or near, ground level. Two long stems of banana plants are placed along the bottom of the screen and the sharp, pointed ends of the main control rods are plunged into the stems to hold the puppets securely when they are off stage, the good characters on the right and the evil on the left, from the puppeteer’s perspective. With the puppets arrayed in this way, the space between them, which represents the stage, is about 2m wide.

Before the performance, the gunungan, which represents a mountain or a tree, stands in the centre of the stage; the dalang removes this from the screen to signal the start of the performance. Although Java is now mainly Islamic, the plays continue to draw upon the Hindu epic poems, which were introduced to Java from India about 2,000 years ago. However, the stories, numbering about 200, have undergone many changes to both their names and content and now have a distinctly Javanese flavour. They reflect Javanese attitudes and values and are very much part of Javanese culture and its national heritage.

Traditionally, a single oil lamp was hung above and behind the screen as the sole source of illumination and this flickering light, coupled with the beautiful figures and the gamelan music, created an amazing, almost hypnotic effect.

THAILAND

Shadow theatre in Thailand is also said to have originated in India and includes the nang talung puppets which are similar in form to the wayang kulit and still to be seen, and the nang yai, which is very different from the examples described earlier and now rarely if ever seen. Essentially a form of folk theatre, the nang yai figures depicted an entire scene rather than individual characters. They were made from cow or buffalo hide and treated in a similar way to the Javanese figures before their construction.

The character and the scene in which it is set was cut in one large piece of hide, which could be as much as 2m high and 1.2m wide (7ft×4ft). Sometimes figures were coloured for use in daytime performances while plain figures were used for performances at night. Each figure was supported by two long sticks which the performer held aloft, most frequently in front of the large white screen, taking it behind the screen to cast shadows by firelight to suggest action at a great distance. In order to contain such large figures the screen was up to 12m long and over 4m high (40ft×14ft). The performer’s dancing movements, resembling the Khon classical dance, coupled with the flickering light of the fire and the design of the figure all contributed to give life to the static images.

A nang talung shadow puppet from Thailand.

A Cambodian figure similar to Thailand’s nang yai figures.

The performances, based upon Thai dance dramas of the Ramakien (the Thai Ramayana), were presented with narration accompanied by percussion and stringed instruments. Performance styles similar to the nang talung and the nang yai are to be found in Cambodia and in other parts of the east, but the nang yai type of performance is less common than those that use individual puppet figures.

CHINA

It is widely held that shadow play in China dates back at least 2,000 years and possibly much earlier, but the first written or pictorial evidence found dates from the Sung dynasty (AD960–1279). Writers suggest that it reached its height of artistry in the eleventh century and that this is the origin of the shadow play in the Middle East, introduced by Mongols in the thirteenth century. Indeed, some suggest that here lie the origins of shadow play throughout the east, if not the world.

The traditional Chinese shadow play is stylized, containing romance, heroic adventure, fantasy and humour. The shadow puppets are usually quite small, delicate and elaborately decorated. There are two types of traditional figure which are distinguished by their size, method of construction and the positioning of the control rods. The Peking (northern) shadow puppets are just over 30cm (12in) high and intricately made from the belly of a donkey. The hide is treated to make it translucent and then brightly coloured with dyes. The Cantonese (southern) figures are larger and of thicker skin so that they cast a more solid shadow.

Each figure has three controls consisting of wires that are fastened in rods, the main supporting control and a control to each hand or arm; the legs hang freely. The main rod on the Cantonese figures is attached at right angles to the head so it is less visible on the screen. The main supporting rod on the Peking figures is held parallel to the body and the top of the wire is bent at a right angle to attach it to a hide collar at the puppet’s neck. The collar is used because the heads are often interchangeable so that several heads may be used with one body. These rods are more visible on the screen but they are clear of the puppet’s shadow.

Old Chinese human figures; the controls would be fixed into wooden rods.

Old Chinese animal figures.

The heads have to be readily distinguishable; the faces are stylized, always depicted in profile, and those of rulers, heroes and women are heavily cut away, leaving only a very thin outline. Bodies are created in different ranks so that any head of a certain rank may be easily matched with an appropriate body. Arms and legs are articulated and sometimes there are also wrist joints. Traditionally, the heads were always removed at night because of the ancient belief that otherwise the puppets would then come to life. The figures were stored in a muslin book or a box lined with fabric and some puppeteers even took the precaution of storing heads and bodies in different books.

The shadow screen, made of white translucent cloth, is approximately 1.5m wide and 1m high (5ft×3ft). It is supported by a bamboo framework with bright drapes surrounding the screen. Scenery tends to be simple and symbolic and, as elsewhere, traditional lanterns have increasingly given way to electric lighting for illumination.

TURKEY

Many scholars consider the origins of shadow play in Turkey to reside in Indonesia but some authorities advance the theory that shadow players were introduced to Turkey from Egypt by Yavuz Sultan Selim, who conquered Egypt in 1517. Yet another theory suggests that the popular Turkish shadow show featuring Karagöz and Hacivat originated in the fourteenth century. Certainly Karagöz is regarded by many as the most important entertainment of the Ottoman period. It was played throughout Ramadan, during other festivals and special occasions and appeared in coffee houses and public gardens. The performances reflected the culture of Istanbul whence it was spread to other parts of Anatolia by travelling performers, possibly reaching its peak of popularity in the eighteenth century. The name Karagöz is a compound of kara, meaning black, and göz, meaning eye, for he is always depicted with one dark eye.

The Turkish Hacivat and Karagöz.

A tradition that survives to this day, Karagöz is a popular, witty, folk hero who has always commented on social events and poked fun at authority with a knockabout style of comedy combining satire and irony, clever plays on words, double meanings and exaggerations. Some commentators suggest that there are also elements of philosophy and Islamic mysticism, the other main character being Hacivat, who, in contrast to Karagöz, is educated in Islamic theology. The performances conclude with an apology to the audience for any errors made during the show. There is also said to be an extinct form of Karagöz play, known as ¸Sekerli Karagöz (Sweet Karagöz), or Toramanlı Karagöz (meaning young, wild or untamed), in which the language was coarse and vulgar. Female characters were naked and Karagöz, depicted with a phallus, performed graphically explicit sexual acts on women and young boys.

The puppets are jointed, between 30 and 40cm high (12–16in), and generally made from camel or cow hide which has been treated to make it translucent. Some accounts suggest that the very first figures were made from leather slippers. Details are cut with sharp blades and colour is added with Indian inks or natural dyes.

The name for the screen, which is held by a wooden frame, actually means ‘mirror’. At one time it was 2.5m wide by 2m high (8ft×6ft), but now it is often scaled down to less than half this size. Scenery is depicted by cut-out sets placed to the sides of the screen and easily interchanged. Behind and below the screen is a wooden ledge on which are placed instruments such as cymbals, a tambourine and pipes; the ledge is also used to hold a string of electric lights, which have replaced the traditional lantern. The closeness of the lights to the screen renders the horizontal control rods very faint, if not invisible, but causes the shadows to fade from view if the puppets are moved only slightly away from the screen. The performances are given by a single player who may sometimes have an apprentice or assistant. The puppeteer operates all the characters, speaks for them in a variety of dialects, for many ethnic groups are represented, and chants or sings songs too.

Today, live Karagöz performances are not so common but are most often seen in tourist hotels and restaurants. It, however, frequently appears in cartoon format on Turkish television. A fascinating feature of the televised Karagöz cartoons is the way in which they have remained true to the idiosyncrasies of shadow play. When other popular images are made into cartoons, they usually adopt the conventions of cartoon film, making all manner of actions or incredible events possible, but, in this instance, the figures retain the characteristics of shadow puppets. For example, they continue to move in the somewhat jerky fashion of the live puppets and they exit backwards because the puppets cannot turn around. In this way the Karagöz cartoons come as close to the live show as it is possible to be.

GREECE

There are many conflicting theories of the origins of the Greek Karaghiosis shadow play that closely resembles the Turkish Karagöz. Some suggest that it was carried from China by Greek merchants, others that it was invented by a Greek during Ottoman rule; the legend of Karagöz and Hacivat working in Bursa is also offered as another explanation. It is quite widely held that it actually came to Greece from Turkey in the nineteenth century and that a significant element in its appeal at that time was the character’s large phallus and its obscene actions and language. The character has since become adapted and integrated into Greek culture as a firm part of folklore. The Greek version is poor, barefoot and hunchbacked with tattered clothes. His right arm is always shown as very long, usually with several joints. He lives in a modest cottage with his wife and children and devises a host of mischievous ways to obtain money and feed his family. He is a liar, sometimes violent, yet good hearted and faithful. There appear to be two types of Karaghiosis play, the comical type and that known as ‘heroic’, set in Ottoman times, in which Karaghiosis appears as the assistant of an important hero.

Puppeteers do devise their own original stories, but there are many handed down by oral tradition and played according to a conventional formula with only minor variations among performers. Students of other forms of puppet theatre will see the many similarities that exist between this Greek or Turkish tradition and the western figure of Punch, another anti-hero who pokes fun at authority and is depicted with a hunchback and a stick that has replaced the original phallus. He too is violent, a liar with mischievous qualities and originally there were some crude aspects to his performance, which has also been handed down largely by oral tradition.

The puppets are created and presented in much the same way as their Turkish counterparts. They are made from camel skin and always shown in profile. Many of the characters have simple joints while two have neck joints and an articulated head. Most of the puppets are operated by a single horizontal rod, though Karaghiosis and a few others require hand controls too. Traditionally, the scenery consists of his cottage at one end of the screen and the vizier’s palace at the other.

Hatziavatis and scenery from the Greek version of Karaghiosis.

Ombres Chinoises: a French proscenium and performance of Le Pont Cassé (The Broken Bridge).

During the 1980s Karaghiosis performances were televised weekly, either as live shows with an audience or pre-recorded with special effects. They included a mix of themes from Greek myths to modern items such as trips into space. Now live shows are less common, Karaghiosis appearing mainly at festivals or folk events. The name is also now taken to mean ‘joker’ and is used as an insult.

WESTERN SHADOW THEATRE