Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

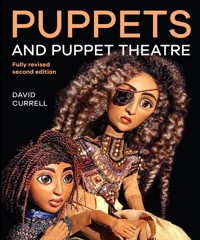

Puppets & Puppet Theatre is essential reading for everyone interested in making and performing with puppets. It concentrates on designing, making and performing with the main types of puppet, and is extensively illustrated in full colour throughout.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 378

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Sarah Wright performing a puppet made by Lyndie Wright for Kneehigh Theatre’s production of The Tin Drum.

CONTENTS

1. An Introduction to Puppet Theatre

Puppet theatre heritage

The nature of the puppet

Types of puppet and staging

Using this book

2. The Anatomy of a Puppet

Principles of design

Proportion and design

Size, weight and balance

Puppet structure

Glove puppets

Hand puppets

Rod puppets

Animal rod puppets

Tabletop (Bunraku-style) rod puppets

Hand-and-rod puppets

Rod-and-hand puppets

Rod-marionettes

Marionettes

Animal marionettes

3. Heads – Materials and Methods

Tools

Exploring materials

Sculpting

General principles

Reticulated foam

Styrofoam (polystyrene)

A template for sheet materials

Plastazote

Worbla

Wood

Modelling

General principles

Paste and paper

Paper pulp

Plaster and muslin

Modelling clays

Milliput (epoxy putty)

Smooth-On Free Form™ AIR

Aves Apoxie Sculpt

Rhenoflex

Varaform

Jesmonite

Fibreglass

Casting

General principles

Making a plaster cast

Casting a rigid head

Casting a latex-rubber head

Painting and finishing head, hands and feet

Principles for painting the face

Materials and methods

Eyes

Hair

4. Construction Techniques

Heads

Necks and neck joints

Neck separate from head and body

Neck built on to the head

Neck built on to the body

Moving eyes

Moving mouths

Hand puppets

Rod puppets and marionettes

Bodies for glove and hand puppets

A glove puppet body

Animal bodies for glove puppets

Animal bodies for hand puppets

Mouth puppet bodies

Rod puppet shoulder blocks

A supporting collar

Cord fastening

A rod puppet body on a shoulder block

Bodies for rod puppets and marionettes

A modelled body

A carved body

A cast body

A wood and foam-rubber body

Animal bodies

Waist joints

Arms, elbows and shoulder joints

Arms

Elbow joints

Shoulder joints

Hands and wrist joints

Hands

Wrist joints

Legs and knee joints

Glove puppet legs

Carved and dowelling legs

Plywood legs

A strap joint for knees

Latex-rubber legs

Hip joints

Joints for animals

Feet and ankle joints

Carved and modelled feet

Open mortise-and-tenon ankle joint

Latex-rubber feet

Giant puppets

3D-printed puppets

Costume

5. Control and Manipulation

Glove and hand puppets

The glove puppet

Hand puppets and mouth puppets

Rod and tabletop puppet controls

The central control rod

Controlling the hands and legs

Rod puppet combinations

Rod puppet manipulation

Marionette controls

The upright control

The horizontal control

The horizontal control for animals

Stringing the marionette

Marionette manipulation

The upright control

Manipulating the horizontal control

Manipulating the horizontal control for animals

6. The Shadow Puppet

Principles

Construction

Simple shadow puppets

Articulated shadow puppets

Decoration and colour

Three-dimensional puppets and human actors

Tricks and transformations

Full-colour puppets in the traditional style

Control

Principles

Methods of fixing main controls

Arm controls

Leg control

7. Staging Techniques

Staging principles

General staging structures

Tabletop (Bunraku-style) performing

Simple staging: a tabletop theatre

Flexible staging units

Stages and scenery for glove, hand and rod puppets

An open booth

A proscenium booth

Accessories

Scenery

Stages and scenery for marionettes

Staging

Accessories for marionette stages

Scenery

Staging for mixed puppet productions

Curtains and backcloths

Drapes for the stage

Proscenium curtains

Backcloths and backscreens

Staging for shadow puppets

Stage construction

The screen

Scenery

8. Lighting and Sound

Lighting the puppet theatre

Different types of lighting

Lighting principles

Lighting for glove and rod puppets

Lighting for Bunraku-style tabletop puppets

Lighting for marionettes

Lighting for shadow puppets

Colour lighting

Lighting control

Starting out

Organising the lighting

Black light technique

Ultraviolet lighting

Black light theatre

Sound

Practicalities

A professional sound system

Creating the soundtrack

Sound playback

9. The Performance

Essential considerations

Variety shows and vignettes

Plays

Principles for adapting a story

The scenario and script

Design and construction

Music for the show

Voice work and recording techniques

Manipulation and movement

Rehearsal

The performance

Further Information

Contributors

Index

Acknowledgements

CHAPTER 1

AN INTRODUCTION TO PUPPET THEATRE

Puppet theatre heritage

Puppetry and puppet theatre have a long and fascinating heritage. The origins of this visual and dramatic art are thought to lie mainly in the East, although exactly when or where it originated is not known. It may have been practised in India 4000 years ago: impersonation was forbidden by religious taboo and the leading player in Sanskrit plays is termed sutradhara (‘the holder of strings’), so it is likely that puppets existed before human actors.

Tiny Tim, a Bunraku-style puppet, one metre tall and constructed in fine detail by Raven Kaliana for Dickens’ A Christmas Carol.

In China, marionettes were in use by the eighth century AD and shadow puppets date back well over 1000 years. The Burmese puppet theatre had a significant influence on the development of the human dance drama, and a dancer’s skill is still judged on his or her ability to recreate the movements of a marionette. And Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653-1725), Japan’s finest dramatist, wrote not for human theatre, but for the Bunraku puppets which once overshadowed the Kabuki in popularity; Bunraku is a blend of the arts of puppet theatre, narration and shamisen music.

In Europe, the puppet drama flourished in the early Mediterranean civilisations and under Roman rule. The Greeks may have used puppets as early as 800 BC, and puppet theatre was a common entertainment – probably with marionettes and glove puppets – in Greece and Rome by 400 BC, according to the writings of the time. In the Middle Ages, puppets were widely used to enact the scriptures until they were banned by the Council of Trent. Since the Renaissance, puppetry in Europe has continued as an unbroken tradition.

Javanese wayang golek rod puppets.

Sicilian puppets – knights one metre (three feet) high, wearing beaten armour and operated from above with rods – have performed the story of Orlando Furioso since the sixteenth century, but this type of puppet was, in fact, in use as long ago as Roman times. In Germany, puppets have performed The History of Doctor Faustus since 1587, and in France marionette operas became so popular that in 1720 live opera attempted to have them restricted by law. The eighteenth-century French Ombres Chinoises shadow puppets were not only a fairground entertainment but were popular among artists and in the fashionable world.

A traditional carved Burmese marionette.

A Chinese shadow puppet created in leather, which is treated to make it translucent and coloured with dyes.

A Sicilian rod-marionette by the Cuticchio family, Palermo.

In England, puppets were certainly known by the fourteenth century and, during the Civil War, when theatres were closed, puppet theatre enjoyed a period of unsurpassed popularity. By the early eighteenth century it was a fashionable entertainment for the wealthy, and in the late nineteenth century England’s marionette troupes, considered to be the best in the world, toured the globe with their elaborate productions.

The ubiquitous Mr Punch originated in Italy. A puppet version of Pulcinella, a buffoon in the Italian Commedia dell’ Arte, was carried throughout Europe by wandering showmen and a similar character – including Petrushka (Russia), Pickle Herring, later Jan Klaassen (Holland), and Polichinelle (France) – became established in many countries. The French version was introduced to England in 1660 with the return of Charles II; it became Punchinello, soon shortened to Punch, and enjoyed such popularity that the character began to be included in all manner of plays. By 1825, Punch was at the height of his popularity, and the story in which he played had taken on its standard basic form.

In the nineteenth century the puppet show was taken to America by emigrants from many European countries, and their various national traditions laid the foundations for the great variety of styles found there today.

Eastern Europe had early traditions of travelling puppet-showmen but, with a few exceptions, puppetry did not develop significantly there until the twentieth century when it was influenced, first between 1925 and 1948, by the work of Professor Richard Teschner. He was an Austrian who developed an intricate form of rod puppet inspired by the Javanese wayang golekpuppets. Rod puppetry in Eastern Europe really progressed after 1945 when it was taken up by Russian puppeteers, also inspired by the Javanese puppets and the Japanese Bunraku. Rod puppetry then developed at an impressive rate under the direction of Sergei Obraztsov at the Moscow State Central Puppet Theatre and had a major influence on its use worldwide.

The twentieth century brought new materials and techniques at a time when melodramatic themes and circus-style acts had little place alongside the prevailing artistic Realism, but the symbolism of puppet theatre provided inspiration for sophisticated artists.

Puppet theatre also saw a revival of interest in the art through film and television. Lotte Reiniger’s shadow film, The Adventures of Prince Achmed, was created between 1923 and 1926 and was the first full-length animated film in the history of the cinema. Puppets have a special place in television history; they were involved in John Logie Baird’s early television experiments in 1930, and the first puppet production was broadcast in 1933. Since this time, puppets have featured continuously in children’s television, but there have also been significant programmes aimed at an older audience, for example the satirical Spitting Image.

Jan Klaassen, the Dutch equivalent of Mr Punch, performed by Egon Adel, Poppenkast op de Dam, Amsterdam.

A scene from Lotte Reiniger’s film, The Adventures of Prince Achmed. Note how layers of tissue paper were used to create depth in the scene.

Some programmes, such as the ‘Supermarionation’ programmes of the 1960s (Thunderbirds, Captain Scarlet and the Mysterons, Fireball XL5 and Joe 90), have now attained almost cult status. In the USA, Sesame Street had a major impact and led to The Muppet Show, which was estimated to have been watched by more people in more countries than any other form of entertainment.

By the second half of the century, some solo artists and puppet companies were producing work of a quality that could not be ignored and, in Britain, a few influential permanent puppet theatres were established (Harlequin, Little Angel, Cannon Hill, Polka, Norwich, Biggar) along with major touring companies (Caricature, DaSilva, Playboard, Theatre of Puppets). In the latter part of the century, official recognition of puppetry as a performance art was achieved in Britain, and there is now widespread awareness of all types of puppet from traditional figures to Muppet-type characters, giant processional puppets, and those used in major theatrical productions. Now puppets are seen alongside actors on the professional stage, sometimes with significant roles such as in Life of Pi and War Horse.

A giant skeleton by Bryony McCombie Smith for a production of Paa Joe and the Lion.

Little Monkey & Sue, performed by actress-puppeteer Andrea Sadler in a fast-paced, complex, highly disciplined performance in which the performer constantly switches between performing out to the audience and moving the focus to the puppet.

A royal Bengal tiger, puppet design by Nick Barnes and Finn Caldwell for the award-winning West End and Broadway production of The Life of Pi.

Kevin, operated by actor-puppeteers, in Low Life by Blind Summit Theatre, a darkly humorous series of vignettes inspired by the writings of Charles Bukowski.

The Explorer, an open-stage marionette performance by expert puppeteer Lori Hopkins, dressed in keeping with the theme of the performance.

Sola the Dragon, a ‘costume puppet’ created from soft foam, Plastazote and Worbla by Bryony McCombie Smith, who performs as the baby dragon’s keeper. The Dragon and Her Keeper is a walkabout show in which the public interact with Sola, whose eyes, spine and horns glow: it works as a daytime and evening piece.

There has also been an emergence of the actor-puppeteer and the musician-puppeteer, together with courses in puppet theatre in universities and drama schools, and courses mounted independently by accomplished performers and craftspersons. Actors not only appear alongside puppets but operate puppets themselves, and even switch roles onstage from puppeteer to actor. The rise of the actor-puppeteer has been accompanied by a shift to presentation styles without a booth or proscenium theatre.

While operators in full view have traditionally worn costume in subdued colours to blend into the background, some are now dressing in costumes in keeping with the theme of the performance or in a style similar to the puppet. Another development is the ‘costume puppet’, a puppet carried or worn by the puppeteer dressed in a costume that is either an extension of the puppet or a character in relationship to the puppet.

In the past 40 years, materials and technology have developed perhaps faster than ever before. This is evident in the many possibilities for puppet construction, scale and presentation, while major developments in technology have transformed lighting and sound in puppet theatre, as they have in theatre more widely. Nevertheless, the principles inherent in puppet theatre remain largely unchanged.

The nature of the puppet

The survival of puppet theatre over some 4000 years owes a great deal to man’s fascination with the inanimate object animated in a dramatic manner, and to the very special way in which puppet theatre involves its audience. Through the merest hint or suggestion in a movement – perhaps just a tilt of the head – the spectator is invited to invest the puppet with emotion and movement, and to see it ‘breathe’.

A puppet is not an actor, and puppet theatre is not human theatre in miniature. In many ways, puppet theatre has more in common with dance and mime than with acting. Puppet theatre depends more upon action and less upon the spoken word than the actor does; generally, it cannot handle complex soul-searching, and it is denied many of the aspects of non-verbal communication that are available to the actor. But the puppet, still or moving, can be as powerful as the actor.

The actor represents but the puppet is. The puppet brings to the performance just what you want and no more; it has no identity outside its performance, and brings no other associations on to the stage. The puppet is free from many human physical limitations and can speak the unspeakable, and deal with taboos. The power and potential of the puppet has attracted artists such as Molière, Cocteau, Klee, Shaw, Mozart, Gordon Craig, Goethe and Lorca, who have all taken a serious interest in this art – one of the most liberating forms of theatre.

In recent years, some practitioners have widened the scope of the debate around what constitutes a puppet; they may use no puppets in a form that traditionalists would recognise. Perhaps their performance will feature pieces of wood or other materials that are shaped and reshaped without taking on a typical ‘puppet’ form, or props and sets may take on character in what may be termed ‘visual’ or ‘object’ theatre.

Petrushka, designed and made by Lyndie Wright for the Little Angel Theatre’s production of the same name.

Tabletop puppets by Raven Kaliana for Hooray for Hollywood, a play and film created to raise awareness of human trafficking. Semi-translucent construction evokes the vulnerable nature of the child characters. Roughly sculpted faces and tattered, fabric bodies reflect the devastating impact of the story’s events.

Fiddlesticks Metronomus, designed by Michaela Bartonova for Garlic Theatre’s Fiddlesticks, a musical journey in which puppets made from old instruments spring to life.

Types of puppet and staging

Most types of puppet in use today tend to be filed under four broad categories: hand or glove puppets, rod puppets, marionettes and shadow puppets. There is also a variety of combinations of puppet types, often involving some control with rods, as detailed in Chapter 2. Among these are glove-rod, hand-rod, rod-hand and rod-marionette puppets, while giant processional puppets often have some rod controls. Puppets similar in style to Bunraku figures have become extremely popular among puppet companies. These tend to be characterised as rod puppets too, although some may have only a short control rod to the head. There is also a range of other related techniques, from masks to finger puppets, from the toy theatre to animated puppet film.

The glove puppet is used like a glove on the operator’s hand; the term ‘hand puppet’ is sometimes used synonymously but here it describes figures where the whole hand is inserted into the puppet’s head. Glove puppets are quite simple in structure but hand puppets often have a costumed human hand, or arms and hands operated by rods. These puppets, although limited in gesture to the movement of one’s hand, are ideal for quick, robust action and can be most expressive. The live hand inside the puppet gives it a unique flexibility of physique.

The highly acclaimed production of The Adventures of Curious Ganz, used Bunraku-style tabletop puppets.

Snitchity Titch, made by Violet Philpott in the early 1960s, was given to Ronnie LeDrew to create his solo glove puppet show. The latex-rubber head lasted a few years; a replacement was made by Caroline Astell Burt from cloth moulded into shape, painted with a sealant, and decorated. The eyes are drawing pins and the hair is strips of leather.

The rod puppet is held and moved by rods, usually from below but sometimes from above; those in the Japanese Bunraku style, now often referred to as tabletop puppets, may require two or three operators, who hold the puppet in front of them. Rod puppets vary in complexity, ranging from a simple shape supported on a single stick to a fully articulated figure. They offer potential for creativity in design and presentation, and their range of swift and subtle movements enables them to deliver anything from sketches to large dramatic pieces.

In many countries the term ‘marionette’ embraces all types of puppet, but in English-speaking countries it tends to be reserved for a puppet on strings, suspended from a control held by the puppeteer. It is versatile and can be simple or complex in both construction and control. Performances can be graceful and charming, but fast and forceful action is generally avoided. For manipulation, the experienced puppeteer draws upon the marionette’s natural movements to great advantage.

Shadow puppets are normally flat cut-out figures held against a translucent, illuminated screen. They may be solid or decorated black figures, full-colour translucent figures, or figures that combine a range of solid, textured and coloured materials. Shadow puppets are ideally suited to the illustration of a narrated story, but they can also handle direct dialogue and vigorous knockabout action. It is not uncommon for shadow play to involve a combination of live actors and puppets.

Starchild, by Barry Smith’s Theatre of Puppets, combined different types of puppet, masked actors and folk-rock music by Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young. The production was based upon Grimm’s The Giant with the Three Golden Hairs.

A hand-and-rod puppet by Max Verstappen. One hand manipulates the puppet’s mouth and body while its hand rods are operated by the puppeteer’s other hand.

Shadow play is also a very suitable medium for film, whether straightforward action or animated film shot frame by frame. Its potential to transform images, or play with size and scale, provide many possibilities in addition to narration, dialogue and wordless action.

Increasingly, puppeteers are exploring the use of space instead of restricting themselves to the confines of the conventional booth or stage. However, glove puppets are usually presented from within some form of staging. The traditional covered booth is still used for Punch and Judy, but an open booth without a proscenium has become popular for other shows as it affords far greater scope for performance, as well as a wider viewing angle.

An example of a beautifully carved 66cm (26in) wooden marionette by the late John Thirtle. It has nine strings, an upright control, and is used to demonstrate manipulation by Ronnie LeDrew, one of the UK’s foremost puppeteers and President of the British Puppet and Model Theatre Guild.

The Old Miller and the Lucky Lad from The Devil with the Three Golden Hairs, part of a longer, scrolling piece of shadow scenery, by Charlie Scullion and Victoria Narewski of The Clockwork Moth.

A Squirrel in Three Parts created by Lori Hopkins for the Bristol 48-hour Puppet Film Challenge.

Rod puppets may use an open booth, but they are increasingly used in less traditional settings. The ‘tabletop’ rod puppet, adapted from the Bunraku style of performance, has become extremely popular; it tends to be smaller in scale and, as the name implies, is frequently performed without traditional staging.

Marionette performances are frequently presented on an open stage with the puppeteer in view. This has long been the case with variety-style acts, but has become more common in recent years for plays. The large marionette stage with a proscenium to hide the operators tends to be used for plays in more permanent situations. Touring a proscenium stage that includes a bridge is possible, but one must consider portability, setting-up time, size and headroom in different venues. Shadow puppets are traditionally performed against a translucent screen, but a great deal of ingenuity has been displayed by performers in their use of multiple screens, projections, superimposed images, alternative shadow stages and moving light sources.

It is possible to combine or alternate the use of different types of puppet in one performance. Used with other puppets, shadow play can illustrate linking narrative, portray distant action and, for example, dream, memory and underwater sequences. The staging demands of some puppet combinations can be considerable; for example, if rod puppets operated from below are combined with marionettes operated from above. However, the shift from a booth or proscenium theatre to the open stage has made such combinations easier to achieve.

Using this book

Many aspects of the design and construction of the puppet are interdependent. For example, decisions about the performance will affect the type of puppet and staging methods to be used, and a head cannot be made for a rod puppet or marionette until it has been decided how the neck is to be joined to the body or whether the neck is to be created separate from, or integral to, the head. It is important, therefore, to design and make the puppet according to the advice given in all of the chapters; try to resist the temptation to launch into making a puppet with little idea of what the puppet will be required to do. Time spent reading and planning will be a worthwhile investment.

CHAPTER 2

THE ANATOMY OF A PUPPET

Principles of design

The puppet is both an essence and an emphasis of the character it is intended to reflect. The puppet artist has to create and interpret character, not imitate it, so the puppeteer’s art involves simplification and selection, identifying the key elements that make us believe in the characters. It offers freedom not only to design the costumes of the actors, but also to create their heads, faces, body shapes and so on.

The Spectre’s Bride: a small marionette of the spectre, carved by John Roberts from a sketched design drawing and a clay maquette of the head.

At this early stage you need to be clear about whether you want to make a particular type of puppet or whether you are open to deciding this in relation to what you want to perform, because not every style of puppetry is suitable for every show. And do the puppeteers want, or need, to be hidden? This also influences the type of puppet you might use and whether the puppet is to be limited to performing within a stage or a booth, or behind a screen. In deciding this, remember that the way in which an audience focuses upon the puppet makes the puppeteer ‘invisible’.

Having considered what each puppet is required to do, and the type of puppet you plan to make, you need to create a puppet that looks and moves like the character you wish to convey. You can now design a specific puppet for that purpose, but remember that it may be necessary to adjust your design and explore different techniques as the puppet progresses.

Often beginners make puppets by drawing upon what they think they know about people: they make children small, adults bigger, and try to convey all the character in the face. The result is puppets that are less than convincing. You must conceive the design as a whole, and for this you need to observe and analyse what you see. Like an artist, study natural form and interpret it by searching for the underlying structures and working on these. Look to the basic structure and see how it gets its form.

My Sister, the Fox: proportions of an adult face carved by Buba.

My Sister, the Fox: proportions of a child’s face.

In principle, keep your designs bold and simple, with clean lines, to achieve greater dramatic effect; delicate features, however beautiful, will be lost on the puppet stage. A puppet that lacks bold design may appear nondescript from only a few feet away, while too much facial detail may hinder the conveying of character. Glove puppets often have large features and bright colours that make them easier to see. Also note the importance of the eyes; they bring the face to life perhaps more than any other single feature.

It is useful to keep a scrapbook for inspiration and ideas: include drawings, pictures of people of all ages and types, in uniform or costume, features, cartoons and articles, for example, on make-up or hair-styles.

The Devil from Stravinsky’s A Soldier’s Tale, the Little Angel Theatre.

Proportion and design

Strict adherence to the ‘rules’ of proportion does not make an interesting and effective puppet, and a puppet made to human proportions may look unnatural. However, it is worth considering certain guidelines with regard to proportion.

The adult human head is approximately one-seventh of a person’s height; for a puppet, it is often about one-fifth, but could be any size you choose. On humans and puppets, the hand is approximately the same size as the distance from the chin to the middle of the forehead, and covers most of the face. The hand is also the same length as the forearm and as the upper arm; feet are a little longer. Elbows are level with the waist, the wrist with the bottom of the body and the fingertips halfway down the thigh. The body is generally a little shorter than the legs.

Pay attention also to the bulk of the body and the limbs. A common mistake is to make the puppet too tall and thin, lacking any real body shape, particularly in profile. Hold the puppet between a strong light and a blank wall and examine the shadows it casts: strongly designed puppets will create strong, interesting shadows. Ensure that the neck, arms and legs have sufficient bulk in relation to the head and body. Even when covered with clothes, it is noticeable if limbs are too skinny.

The head can be divided into four approximately equal parts – the chin to the nose; the nose to the eyes; the eyes to the hairline; and the hairline to the top of the skull, which is slightly smaller than the other sections. The eyes are approximately halfway between the chin and the top of the skull. The top and bottom of the ears are normally in line with the top and bottom of the nose.

Avoid putting the eyes too high in the head or too close together, the forehead too low, and the ears too high or too small for the head. Ears should be studied from the side and from behind: they contribute to characterisation more than might be imagined. Viewed in profile, the neck is not in the centre of the head but set further back and possibly angled, depending on character.

However, it is the variations from the norm which are usually most significant in creating a dramatically effective character. For example, the spacing of the eyes depends upon the width of the nose and the characterisation required. The age of a character affects the proportions of the head. ‘Hair’ can completely change the head’s apparent shape, so consider the bulking of your chosen hair material when shaping the skull; different materials, such as thick synthetic fur or dyed string, will have varying influences upon size, shape and, therefore, character.

The angle at which the head sits on the body and the way in which it moves are essential to characterisation, so it is important to consider these points with regard to the positioning of joints between the head, neck and body.

Typical proportions for a puppet.

A design for a tabletop puppet by Lyndie Wright.

Typical proportions for a head: the top of ears aligns with eyes and the bottom of ears aligns with nose. The eyes are approximately one eye’s width apart. A design by Bryony McCombie Smith for Alice (see overleaf).

Alice in Bloody Silly Business. Her head, hands and feet were carved from polyurethane (reticulated) foam, and soft foam was used for the body.

The setting of the head on the neck has a significant influence on characterisation.

Size, weight and balance

Generally, apart from glove puppets, small lightweight puppets do not work well. A puppet needs sufficient weight, combined with suitable joints, to facilitate good control. This is why carved wooden figures that are well balanced have long been popular with many professional puppeteers. Of course, carving or sculpting is not for everyone and some makers prefer modelling, casting or even 3D printing for their puppets, particularly the heads. However, puppets made from a variety of materials do need to be well balanced, so sometimes it may be necessary to experiment with adding a little weight to some parts to see if it improves control.

Size is directly related to weight and control. Increasing the size, and therefore the weight, can make the puppets more tiring to hold for long periods and more difficult to control, as well as requiring larger props with attendant issues for transportation. 50cm (20in) marionettes actually carry satisfactorily to a fair-sized audience. Weight is equally significant for hand and rod puppets, which have to be held high for quite long periods without sagging.

Early on I realised that it is not necessary to make rod puppets or marionettes with moving eyes or mouth, unless it is needed for a particular effect. For these types of puppet, attempting to move a mouth to every syllable of speech impedes good manipulation. Overall movement and gesture are more effective in suggesting that the puppet is speaking.

Puppet structure

Glove puppets

Glove puppets are constrained in size and design by the need to contain a human hand. The operator’s wrist becomes the puppet’s waist, so it is important to have a long ‘glove’ almost to the elbow, so that your arm does not show while performing. If you use a basic glove body on which to add the costume, use a dark material to help it recede, or a neutral colour, if that blends in more effectively.

The neck is usually slightly bell-bottomed, to assist in securing the glove body. The recommended method of operation is with index and middle fingers in the neck, thumb in one arm, and ring and little fingers in the other. This enables turning the head by moving the fingers inside the neck, rather than having to turn the whole body, and it facilitates more secure handling of props.

The puppet’s hands may be made as part of the glove, separately in fabric, or sculpted, modelled or moulded, with a hollow wrist or cuff; its arms are attached securely to the cuff and the puppeteer’s fingers are inserted to control the hands. This allows more character in the shape of the hands but more practice may be needed to achieve expressive gesture and to handle props effectively.

Glove puppets may be given legs. Carve, mould or model the foot and lower leg, and use a fabric thigh. Such legs usually swing freely; you can control them directly with the fingers of your free hand inserted into holes in the back of the thighs, but this limits you to operating only one puppet at a time.

For animal characters, make a simple glove with an animal head, covering the glove with a human costume, synthetic fur fabric, or other suitable material. Alternatively, a complete animal body that rests on the wrist and forearm may be made of cloth and stitched to the glove.

Glove puppets with separate hands attached to a cuff, by Sarah Wright.

The basic glove puppet.

Glove puppets may be given legs and feet.

Dodo bird made by Violet Philpott for Ronnie LeDrew’s glove-puppet production The Snitch and Dodo Show.

A hedgehog glove puppet in which the body effectively sits on the back of the operator’s hand and wrist. Made for Ronnie LeDrew by Caroline Astell-Burt from fur fabric covered with individual nylon brush bristles.

Hand puppets

The term ‘hand puppet’ is used here to describe a puppet in which the operator’s whole hand is inserted into the head. It usually has a moving mouth, operated with the thumb in the lower jaw. It may be a simple sleeve of material with a head attached, sometimes called a ‘sleeve puppet’, which is suitable both for human and animal characters. A stuffed body and dangling legs may be attached to the sleeve.

The crocodile is a form of sleeve puppet padded with foam rubber.

Zippy from the television programme Rainbow is a ‘mouth puppet’, with a gloved human hand. This version of Zippy was made by John Thirtle and manipulated by Ronnie LeDrew.

A hand puppet designed and made by Max Verstappen Puppetry.

If the hand puppet needs to maintain a rigid body shape, it may be made on a framework of strong card or wire netting (chicken wire), which is padded and covered.

A hand puppet may have a disproportionately large head and a very dominant mouth, hence its other name, ‘mouth puppet’. One hand effects head, mouth and body movements. The puppeteer’s other arm and hand are costumed. Alternatively, an additional operator may provide the puppet’s hands. Puppet hands usually have only three fingers – two of the operator’s fingers are fitted into one of the puppet’s – and this tends to look quite natural on the puppet.

Hand puppets tend to be large, so the head should be made of a lightweight material. They are often covered with fabric, such as fleece or synthetic fur fabric. The head is made with a separate lower jaw joined by a strong fabric hinge. Make the body suitably full for the character. The whole puppet may be created in any suitable material detailed in Chapter 3.

Some hand puppet characters provide an opportunity to use them as ‘costume puppets’ (see page 11). They are made in the same way as sleeve puppets and extend the length of the puppeteer’s whole arm to the shoulder, where the puppet is blended into a costume worn by the actor-puppeteer. The puppeteer’s costume may be an extension of the puppet itself or may establish the wearer as a separate character.

Rehearsal experiments with a hand puppet by Raven Kaliana for The Bear Who Went to War. It represents Wojtek, a live bear adopted by the Polish Army in the Second World War. The ‘puppet’ consists of only a head that could be worn as a mask, and hands, as the director, Allan Pollock, asked for the puppeteer to be quite visible.

Rod puppets

The rod puppet is usually supported by a central rod that is free to turn, but may be fixed if desired. Even a head and a robe with no body or limbs can be effective, and the natural movement of the fabric contributes to this. A rod puppet operated inside a stage or booth frequently has a head, shoulder block, arms, hands and robes, but no body or legs, as it is usually visible only to waist or hip level. If it has no body, appropriate padding under the costume assists characterisation. Rod puppets used without a traditional stage often have a full body and legs, like those of a marionette.

A short central rod gives more scope for movement, as the operator’s wrist becomes the puppet’s waist, but a long rod enables the puppet to be held much higher.

It is a simple matter to attach the head to the central rod to permit it to turn and look up and down. If it is only to turn, the head may be constructed with the neck attached, then secured on the central rod. The rod turns inside the shoulder block/body. If the head is to move vertically, construct it without a neck but with an elongated hole in its base; it pivots on the top of the central rod that forms the neck. A pull-string or a piece of stiff wire is then used to control vertical movement. The rod is also able to turn inside the shoulder block or body.

In each case, a supporting ‘collar’ is attached to the rod under the shoulder block or inside the body; this holds the shoulders in place on the rod, but permits turning.

Hand movement is effected by thin but stiff metal rods. If the puppet has legs, they usually swing loose; often, an additional puppeteer is needed if they are to be manipulated.

A rod puppet with a body and legs plus robes and controls can be a considerable weight, so design the puppet and select construction materials and costume fabrics accordingly. The larger the puppet, the more important it is to use lightweight materials rather than wood.

Animal rod puppets

Animal puppets can be made from a wide variety of materials. Two common techniques are to build a head and body by one of the regular methods of modelling, moulding or sculpting, or to create a body around a central skeleton or a core of rope, spring, flexible tubing and so on.

The head and body may be created as a single unit without a joint, but normally the head moves separately from the body, controlled by an extra rod directly to the head or inserted through the body. The supporting rod for the body is attached at a point suitable for good balance.

The legs may be made from the same material as the body if it is suitable, jointed wood, laminated plywood shapes, or in a variety of creative ways (if the puppet is given legs at all).

A basic rod puppet with a shoulder block but no body or legs. The long rod enables it to be held high, but limits body movement.

A short central rod limits the height of the puppet, but permits considerable scope for movement.

For nodding, the head has an elongated hole in the base and pivots on the central rod.

Lorenzo, a rod puppet with legs, by Barry Smith for Theatre of Puppets’ production of Keats’ Isabella (or The Pot of Basil).

Dad Fish, a 50cm (20in) rod puppet by Raven Kaliana, commissioned for the play Where the River Runs. The puppets, which were operated by dancers, had a Plastazote inner construction to create a smooth swimming motion as the central rod rotated.

For an animal rod puppet, a rod to the body often provides the main support while an additional rod controls head movement.

Tabletop (bunraku-style) rod puppets

The term ‘tabletop’ is a contemporary way to describe puppets that are operated at approximately waist height, often on a playing surface, but occasionally without one: with skilful operation the audience is invited to ‘see’ the surface on which the puppets walk. The performers are not hidden. They may be dressed in dark or neutral costumes with carefully directed lighting to focus attention on the puppets, or they may be costumed in keeping with the theme of the performance. Often they will be actor-puppeteers, performing both roles.

The head of a true Bunraku puppet is carved and hollowed, sometimes with a range of moving features. It is mounted on a head-grip, which fits into a wooden shoulder board with padded ends. Two strips of material hang from the shoulders at the front and back; to the bottom of these is attached a bamboo hoop or a piece of wood for the hips. The limbs are carved, often with shaped and stuffed fabric upper parts; strings from the arms and legs are tied to the shoulder board. The costume is padded to create the body shape.

The chief operator inserts his left hand through a slit in the back of the costume and holds the head-grip to control head and body. With his right hand he moves the right arm; a toggle, pivoted in the arm and with strings attached, is used to effect hand movements. A second operator uses his right hand to move the puppet’s left arm by means of a rod about 38cm (15in) long joined to the arm near the elbow. The hand is moved by two strings attached to a small cross-bar on the rod; the operator uses his index and middle fingers hooked around these strings. The legs are moved by a third operator using inverted L-shaped metal rods fixed just above the heel.

Adaptations of this type of puppet are not new but have become more widely used in recent years. Often the figures are relatively small, so there is a significant economy of scale, and, despite their size, they may be operated by up to three people. The puppets will normally have full body and legs, so much of their construction will be similar to that described for marionettes. The head may be controlled by a short rod to the head from inside the body, a rod attached to the back of the head near the base of the skull.

A tabletop puppet from The Three Billy Pigs, a mixture of The Three Pigs and The Three Billy Goats Gruff by Nik Palmer and Sarah Rowland-Barker of Noisy Oyster.

The structure of a Bunraku puppet.

The hand is attached to the arm with or without a flexible wrist joint. A control rod, operated from behind, is inserted into the heel of the hand or the arm at the elbow or wrist, as appropriate. The hand-control rod (which may be weighted if required) can act as a partial counterbalance to the arm, so that it does not hang lifeless by the puppet’s side while it is not being operated. Toggle hand controls may be added. Leg control rods may be added at the heels. Some performers omit hand, arm and leg controls, preferring to operate the limbs directly with their own (often gloved) hands. This normally requires more than one operator per puppet.

Pierrot from Pierrot in Five Masks by Barry Smith’s Theatre of Puppets. The puppet is operated in Bunraku style by three people. Different latex-rubber masks fit on to a covered polystyrene head shape.

Hand-and-rod puppets

This is a cross between a hand puppet and a rod puppet, usually with a moving mouth. The operator’s hand is inserted for head, mouth and body movements; the hands and arms are controlled by rods. Jim Henson’s Muppet characters, like Kermit, were often structured like this.

A hand-rod puppet, made by Phil Fletcher, of the type used for many Muppet characters. It has a proportionately bigger head with a moving mouth movement. The eyes were made from plastic teaspoons with black stickers for pupils. The hand rods are covered with a rubber tube, which helps stop the rods slipping when the puppeteer is holding positions.

Rod-and-hand puppets

This type of puppet requires one or two operators. At its simplest it has a central rod and a robe, but no body; usually it has at least shoulders to help establish body shape. The puppeteer holds the rod in one hand and uses the other hand, costumed, as the puppet’s hand, or slips a gloved hand through a slit in the puppet’s robe; the slit may be elasticated if desired. Alternatively, one puppeteer operates head and body and another provides the costumed hands and arms.

A rod-hand puppet with a short central rod and shoulder block, but with gloved human hands.

Rod-marionettes

The term rod-marionette refers to various types of puppet operated from above, like marionettes, either by rods and strings, or just by rods. The traditional Sicilian puppets, carved in wood with beaten brass armour, are operated in this way by strong metal rods to the head and the sword arm, and a cord to the shield arm. Twisting the head-rod from side to side creates sufficient momentum to make the legs swing.

The Sicilian style of rod-marionette has been adapted for Jack from Jack and the Beans Talk by Garlic Theatre. Separate rods to the head and the back permit considerably more head movement.

Some rod-marionettes have two control rods, one attached to the head and another to the back of the body; this design allows more flexible head movement and can be used with long rods or shorter rods for tabletop puppets. An animal can have head- and body-rods, through which total control is effected. When the puppet is standing upright, its momentum and the gentle swaying of its body causes its hind legs to walk; when on all fours, walking is achieved by alternately lifting front and rear rods with slight forward pressure. To reduce the weight, the rods may be constructed from aluminium tube; the puppet also needs to be made from a fairly lightweight material.

Now that performers often appear close to their puppets on the stage, you sometimes see figures, especially animals, where a more complicated marionette control is combined with a control rod. This could be a marionette control for body, legs, and walking action combined with a single rod for very direct head control.

Another rod-marionette of the type used in southern India, often called a ‘body puppet’, is suspended on strings attached to a cloth-bound ring on the puppeteer’s head and controlled by the puppeteer’s head movement and hand rods. Shaped plywood strips attach the puppet’s soles to the puppeteer’s shoes.