14,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Il Leone Verde Edizioni

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

“Maria Montessori, a Relevant Story is the best biography of Maria Montessori that I know of, certainly in Italy, but perhaps also in the world, absolutely of the same value as Rita Kramer’s historical one. Grazia Honegger Fresco is a Montessorian in heart and soul, endowed with a deep knowledge of Maria Montessori’s life and work, and her book is not a dull retelling of news already known, nor a hagiography. The author has done extensive research in Italy and abroad, consulting original and private documents of Maria Montessori and her family, and listening to those who knew Maria intimately. The result is this wholly original masterpiece.” Carolina Montessori (great-granddaughter of Maria)

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Appunti Montessori

12

Grazia Honegger Fresco

Maria Montessori, a Relevant Story

Life, Thought, Memories

Third corrected, enlarged and updated edition edited by Marcello Grifò

Translation from Italian by Ivana Minuti

Il leone verde

This book is printed on paper produced in full compliance with environmental standards.

Collection edited by Rosa Giudetti.

Anita Gazzani is responsible for the graphic design of the cover.

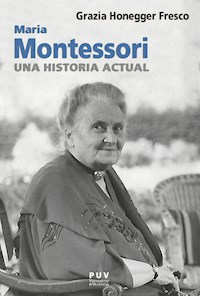

On the cover: the picture was taken by Sandro Da Re, a photographer from Bergamo, who in 1947 took a series of photographs when Maria Montessori was a guest of the Agliardi family in their villa in Sombreno (BG). The Bank of Italy also used this series for the two hundred lira coin and the one thousand lira banknote.

ISBN: 978-88-6580-502-2

Copyright © 2023

All rights reserved.

Edizioni Il leone verde

Via Santa Chiara 30 bis, Turin

Tel. 0115211790

www.leoneverde.it

www.bambinonaturale.it

The weight of the centuries lies on children. (Flannery O’Connor)

To little Laila and to those who, like her, will come in this XXI century, hopes for a more unified and less violent humanity

Editor’s Note

The re-publication of the successful biography of Montessori by Grazia Honegger Fresco more than ten years after its first edition was, first of all, an act of confidence in the relevance of the message it was intended to convey. At the same time, we asked ourselves, with the utmost care that should belong to the reliable and objective scholar, if and what sense it made to put our hands on this undertaking once again. Although valuable and well-documented, all research inexorably suffers the effects of time, and we do not believe that this work will escape the same fate.

In recent years, an impressive quantity of new studies has accumulated, often of high scientific quality, which – sometimes following already traced paths to the end, sometimes opening up new ones – have partly redrawn the biographical and intellectual profile of the scientist from the Marches, offering articulated interpretations and, at times, of radically opposite sign. As a result, the risk that Montessori might be reduced, as some feared, to conventional outlines and handed down to posterity surrounded with incense and enclosed in a sort of laic sanctorale can be said to have been definitely overcome. As the various threads that are woven through the rich fabric of her thought were identified and recognised, and as the weave of her many cultural referents became more evident, so did the contradictions and controversial choices that today – it must be admitted – would not weigh too favourably on the image of a figure of her calibre.

Despite this hard work, the questions raised seem to outnumber the answers provided, and the scientist remains an ideologically uncertain identikit: who was Maria really? The agnostic and lay intellectual, lacking in metaphysical “superstructures”, who was firmly convinced that individual and collective history vectors are found in the physicochemical interactions and socio-economic variables governing human life? The influential personality, linked to mysterious, strong powers, invisible makers of a supranational order? The zealot of doctrines of an initiatory and esoteric nature to whose powerful influence a part of her production would be ascribable? Or was she a sincere believer, a devout Catholic who at a certain moment even thought of consecrating her own life and that of the young women around her to an educational mission illuminated by the light of God? Or was she a sincere believer, a devout Catholic who, at a certain moment, even thought of devoting her life and that of the young women around her to an educational mission enlightened by the light of faith; the author of fine writings on liturgical education and children’s participation in ecclesial life, esteemed by presbyters, religious men and women, such as Luigi Sturzo, Antoni Batlle, Igini Anglés, Vincenzo Ceresi, Marie de la Rédemption, Isabel Eugénie and Luigia Tincani?

In this context, it would be fanciful to attempt to reach an unequivocal and shared veritas on this figure and her thoughts, nor does the present essay attempt to do so. Indeed, the author is convinced that such rigorous and analytical investigations, while desirable and necessary, fall within the historian or documentarian competence and are of lesser importance, in the first instance at least, for those who approach with interest, perhaps for the first time, the extraordinary pedagogical revolution that Montessori theorised and obstinately supported. Montessori’s entire work, as she herself had the opportunity to stress on several occasions, was oriented towards placing the child and his or her authentic needs at the centre of any educational activities, and it would be truly paradoxical if the one who remains among her last living students did not share this assumption. Therefore, the real protagonist of the volume that is now returned to the reader’s discernment is not as much Maria Montessori, the woman, the mother, the scientist, the multifaceted personality known on a global scale as her Method, which paradoxically remains much less known than its creator.

Given this necessary hermeneutical premise, it remains to mention a typical feature of this biography of Montessori. Anyone who would look through it for the rich harvest of information, and bibliographical and archival references that characterise other remarkable writings of the same kind, would be disappointed. They are largely taken for granted. This has been done intentionally, not only in order not to burden a text that is intended to be purely popular but also in order to repropose in it a way of passing on the “history” that belonged to the first generations of Montessorians who have now disappeared. It presents – if I may be allowed to make the comparison – a very strong affinity with that mediation process of a knowledge that in the Jewish educational tradition was carried out through the personal relationship between a teacher and his pupil, experienced in the form of a contubernium and summed up in the binomial qibbel / m’sar, to receive / to transmit.

Similarly, the first “witnesses” of the Method, having known Montessori in class, only became true pupils of the Method by becoming disciples of one of her former companions with whom they had had an intense communion of life and action: Grazia, Sofia Cavalletti and Gianna Gobbi followed Adele Costa Gnocchi; Vittoria Fresco Anna Maria Maccheroni; Costanza Buttafava Giuliana Sorge and so on. For all of them, Montessori’s story was the one they learned from listening to their teachers, and their training never consisted of a set of technical notions to be remembered and put into practice with mechanical precision. This was, for example, the great misunderstanding that Joan Palau i Vera encountered when, after reading The Discovery of the Child and visiting one of the “Children’s Houses” in Rome, he tried to apply it himself in the parvularium he had opened in Barcelona. It was, as we know, a resounding débâcle.

For each of these pioneers of the Method, it was first and foremost a practice, a daily exercise, a constant call to observe and consider the varied and unpredictable demands of the children they met.

Therefore, if in this biography one does not find excessive references to writings, dates, and places, or if one finds minimized information on the long critical discussion that marked the development of Montessori pedagogy, one should not be surprised. On the other hand, the voices of the many early apostles of the Method, who actually made its history and whom all too often others have overlooked, will resound as fresh as ever. The Author met them all, or almost all of them: Paolini, Maccheroni, Sulea Firu, Costa Gnocchi, Guidi, Joosten, just to name a few personalities with whom she spent a long and loving time in the desire to know how it all began. From them, she came to know the “true” story of Maria Montessori, and in this book, she has preserved her priceless memoirs from oblivion.

Along with her story of Montessori fading in, Grazia Honegger Fresco also gives her readers the memories of an entire life spent putting Montessori’s intuitions into practice, dedicated to the care of the child – “father of man” – and she ideally says to those who leaf through her pages: “Tradidi enim vobis in primis quod et accepi”, “For what I received I passed on to you as of first importance” (1 Corinthians 15:3).

Marcello Grifò

Palermo, May 1, 2018

Acknowledgements

In the first edition, I wrote an affectionate thanks to my trusted readers: Sara and Fulvio Honegger, Mariuccia Poroli and Franca Russi, Lia De Pra and Costanza Buttafava. Without their advice, I would not have been at ease. A very special thanks I addressed to Goffredo Fofi, a lifelong brotherly friend, who understood many things about children and adults, and to Renilde Montessori, direct heir of a great thought, who shared my intentions.

In this third edition, I would also like to express my deepest gratitude to Carolina Montessori for the very accurate re-reading of which she has made me a gift on several occasions, uncovering errors and inaccuracies in the history of her great-grandmother and of the family, with the competence that comes to her from personal memories as well as from her current task of reordering and taking care of the M. Montessori Archives at AMI.

Thank you, Carolina; you have been an invaluable friend to me.

Other heartfelt thanks go to engineer Mario Valle and his wife Antonella Galgano, as well as to engineer Germano Ferrara for the technical preparation of the text. I am also very grateful to Marcello Grifò with whom I have constantly shared in friendly synergy the hard work of the preparation of this new edition. I would also like to express my gratitude to Rosa Giudetti, president of the Montessori Association of Brescia, for the commitment she has shown in these years in the divulgation of our educational purposes.

1. Preface

Many times I have ventured to draw biographical notes on Maria Montessori, whose philosophy of life and whose accomplishments have permeated my professional life and my vision of reality, but after some time, having relentlessly continued to search for new documents and data, I have had to note inaccuracies that here, thanks also to the help of Carolina Montessori, I have gladly corrected, availing myself, as always, of additional sources and testimonies.

Maria Montessori’s life, despite its linearity, has many hidden aspects, not least because of her constant travelling. In the course of her existence, she lived in different cities, visited numerous countries, gathering friends and students everywhere, leaving signs of her existence in different places and people, not always easy to connect with. The effort she put into “sowing” the results of her discoveries ended up hiding – and in a way denying – the bright years of her training, coinciding with feminist struggles and the painful experience of motherhood, marked by a new sense of social justice and a new awareness of the role of women. The suffocating bourgeois respectability of the time considered some of her experiences disreputable, to the point of building around her figure a sort of legend.

The first time this work was proposed to me was one hundred years after the opening of the first Children’s House. I accepted with pleasure, deciding to report only documented or certain news, repeated in articles, letters, and photographs of the time, reported by trusted witnesses or personally experienced by me. My intention was to give a clear picture of Maria Montessori, free of hagiographic overtones that do not suit her – yet are common to many biographies – and of gratuitous interpretations, which are anything but rare. In her letters to some of the students I have known – Anna Maria Maccheroni, Adele Costa Gnocchi, Giulia Sorge, Maria Antonietta Paolini – Maria always alternated a confidential or slightly ironic tone with a sort of detachment from things, as she was bent on the future, with her thoughts oriented to the cause of children and young people, to the wellbeing of all humanity through recognition of the rights of the “long human childhood.”

We have seen Maria Montessori on stamps, on two-hundred-dollar coins and thousand-dollar banknotes in the days of the lira, like an old national glory, a paper “holy picture” now consigned to history. An outdated model, one hears people say, that paradoxically now appeals to many in the face of a school that programs, trains, assigns tasks, fills the time of students of all ages to excess, spurs repeated competition, and compels to forced socialization while devaluing individuality. A school that judges without ever judging itself, not preparing teachers for self-criticism. A system, in short, in which children, young people and adolescents are not taken into consideration with their specific needs for growth and their individual differences but are treated as empty vessels to be filled or overprotected and satisfied to the point of making them tyrants who are always unhappy. When will we adults find the right measure?

Since the Second World War, there has been no lack of experiences that have proposed different educational paths: the CEMEA, born in France in 1936 and also known in Italy, the CEIS of Rimini, the Pestalozzi City-School in Florence or the classes created by Mario Lodi and Don Milani. Although much celebrated, they remained isolated cases and did not affect the usual way of teaching. Not even Dewey, who was introduced after World War II by that excellent teacher, Lamberto Borghi, nor Freinet with the Movimento di Cooperazione Educativa (MCE) – a name in itself threatening to the quiet life – found a concrete hearing in the faculties of pedagogy and teacher’s training colleges1.

I remember a school inspector who, in the early 1970s, regarding the self-correcting filing cabinet and the newspaper printed by the children in working classes, denied that they could check their own achievements without trouble or that they could discover the mysteries of spelling, which elsewhere was so awe-inspiring, by handling the type characters themselves. Mistrust, fear of freedom and distrust of forms of learning generate pleasure2.

All the more reason for all these prejudices to apply to a figure as “impertinent” as Montessori3! First of all, a woman. A woman doctor, no less, who believed she had something to teach the professional pedagogues. She studied oligophrenics and claimed to apply the same methods to normal children, coping from the Agazzi sisters and becoming rich thanks to sensory materials and her schools for the children of wealthy families. It was not clear whether she was right-wing or left-wing. She was a positivist, feminist, Mason, theosophist, fascist, and Catholic. From time to time, she was supported by politics or big powers. An unmarried mother who had abandoned her own child to devote herself to the children of others, and a self-regarding scientist, jealous of her ideas. Viewed with suspicion first by the idealist philosophers of her time and later by the active school movement, her educational proposals, while receiving occasional praise from the Catholic Church, have spread mainly in countries of the Protestant tradition and even among Hindus, Sikhs and Shintoists, as well as in many secular schools.

In her day, she was the object of continuous inferences and backbiting. Her marked sense of freedom, the uncomfortable novelty of a way of thinking that demands adults a profoundly changed educational attitude, still disturbs us. Therefore, depending on the case, it has been said that “she gives too much freedom” or, on the contrary, that “she is too rigid” or that her method “does not develop the imagination” and is not adaptable to changing times. It is true that she strenuously defended the integrity of her work. She did not want it to be affected by any compromise nor transformed into a lucrative business. Others have become rich thanks to her name or have used it for different purposes.

Her personal life – of which not much is known, as it has always been marked by great confidentiality – has been written with great ease or even inventing4.

No less unfounded is the position of those who consider her to be a “fossil” in the pedagogical field, obscuring a priori the revolutionary content of her operational strategies, which have been implemented in numerous schools throughout the world, but which have not found a place in Italy because of widespread scepticism and cultural resistance to self-criticism and freedom of thought. To the historical, political and ideological reasons must be added the oppressive weight of bureaucracy and the responsibility of those in Italy who, using her name for façade initiatives, have hastened the disappearance of public and private Montessori schools, even discouraging the spread of training courses for educators and teachers.

Today, in our country, there are only a handful of serious institutions that welcome children between the ages of three and twelve, according to the Montessori formula. By contrast, there are only dozens in the United States and Canada, not to mention the many publications, newsletters, and magazines for parents, training courses for adults who apply the Method in various age groups, and directors and administrators of Montessori schools. Montessori schools of all levels also exist in different European countries – France, Germany, Belgium, Great Britain, Spain, Holland, Sweden, Norway – and non-European countries – Australia, Hong Kong, Mexico, Ecuador, Brazil, Chile, Morocco, South Africa, Tanzania, India – many of which cover the age range from two or three to fifteen, using contiguous spaces to maximize interaction among the various ages, differences – including those of children with difficulties – and the diversity of interests. Most of these institutions are private and not always only for the wealthy; there is also no shortage of public schools, including secondary schools. In Japan, where schooling is highly competitive, schools for children from six to twelve have recently appeared. Several Children’s Houses are beginning to spread even in China and Korea5. In the United States, to the amazement of many people, the children’s home is a place where they can be found. To foreigners’ surprise, there are still few or poorly made in our country, starting with the historic one in Via dei Marsi 58 – the first in San Lorenzo – which a scrupulous scholar in Montessori as Raniero Regni has called “the Pompeii of pedagogy.”

In the U.S., there are now several studies on the results achieved in these institutions6, and there is a wide circulation of Montessori’s work, not only the most famous ones which have become proper classics (in Italy, they are almost all published by Garzanti and unfortunately not always available) but also minor writings, speeches delivered on various occasions or reworkings of lectures she delivered in India or other English-speaking countries and never translated into Italian.

In various North American and European universities, Montessori education is studied for its profoundly innovative content. Whereas, in Italy, where this educational adventure originated, her space is reduced to a few pages in the history of pedagogy textbooks. The only exception is the CESMON created by Clara Tornar at the University of Roma Tre.

Maria Montessori’s educational journey started at the beginning of the twentieth century in a small room in Rome’s working-class district of San Lorenzo, later called Children’s House. It expanded to propose a new image of the child and then of the youth in very different conditions and cultures – no longer a passive receptor of old or new knowledge uninterruptedly ruminated on by generations of adults, but a passionate and responsible individual towards himself and others.

January 6, 2007, marked one hundred years since that first enlightening experience.

It is with full awareness of the weight of this centuries-old history that I will attempt here to retrace the most significant stages of the commitment that Montessori felt she had to undertake by carrying out, in the words of John Dewey, a “new Copernican revolution” – to make the motor of education no longer the adult, but the child himself with his self-forming capacity, reared in a radically transformed living environment, in which the common understanding of the relationship between parent and child, teacher and pupil, is overthrown, to succeed in finding the starting point for the construction of less fierce humanity.

. Today, in this field, there is the exciting example of Franco Lorenzoni with his I bambini pensano grande, Sellerio, Palermo 2016 or even the very recent one, in a different style but equally stimulating, by D. Tamagnini, Si può fare. Lascuola come ce la insegnano i bambini, la meridiana, Molfetta (BA) 2017.

. In an article by Jesuit M. Barbera entitled Modern Humanism, which appeared in “La Civiltà Cattolica” on 3 December 1939, the author, praising the “renewal of the Fascist regime”, added a concluding note of this tenor: “We have dealt several times with the “Active School” and the “new education” based on the naturalism of Rousseau, and tending towards humanitarianism, therefore anti-humanist in a sense contrary to the classical and Christian tradition”.

. In the ironic sense proposed by Piergiorgio Odifreddi of “not belonging”. The original nineteenth-century meaning has become, with use, “shameless”.

. This is the case, for example, with the book by D. Palumbo, Dalla parte dei bambini. La rivoluzione di Maria Montessori, Edizioni EL, San Dorligo della Valle 2005, which unfortunately turned out to be a missed opportunity: intended for children, it has a catchy title, but of decidedly disappointing contents. The author chooses, in fact, to introduce fictitious stories that indulge in astounding anachronisms, such as the imaginary journey made by Maria in Patagonia in the company of Itard, who died – as is known – in 1838, about thirty years before Montessori was born. No less questionable interpretations are found in authors such as Marjan Schwegman and Paola Giovetti.

. Thanks above all to the intelligent work carried out by Giuseppe Marangon, former president of Gonzagarredi.

. The latest research – widely reported in the Italian press – was carried out by psychologist Angeline Lillard of the University of Virginia and Nicole Else-Quest of the University of Wisconsin, which appeared in “Science” in September 2006. With reliable control evidence, it found increased creativity, social integration skills, and speed of learning in children in American Montessori schools.

2. Memories of childhood and family

1870 was a year of significant changes throughout the world: in Europe, the Franco-Prussian war raged, leading to the fall of Napoleon III and the restoration of the republic in France; in Austria and England, laws were passed for the secularization of the State, in the first case with the introduction of civil marriage, in the second with the birth of municipal schools from which any religious instruction was banned; in the United States Congress passed the 15th amendment, according to which the right to vote could not be inhibited on the grounds of race or skin colour. Italian troops enter Rome through the Porta Pia breach in Italy, ending the pope’s temporal power. Pius IX, the last pope-king, did not oppose military resistance, left the Quirinal and took refuge in the Vatican. On 2 October, with a plebiscite, the city was proclaimed capital.

In 1870, the Marches – the region where our story begins – had already been part of the Kingdom of Italy for about ten years. However, the great political events barely touched the life in the quiet towns of the province, such as Chiaravalle, a town a few kilometres from Ancona. Here, on August 31 of that year, the first and only child of Renilde Stoppani and Alessandro Montessori was born. Three days later, she was baptized in the church of Santa Maria in Castagnola – the austere, harmonious abbey dating back to the twelfth century – with the names Maria Tecla Artemisia, the last two inherited from her grandmothers.

The father himself recounts this in the scanty “news on birth and physical and intellectual development” of his daughter, which he wrote many years later. They are simple sheets of paper written in neat, slanting handwriting, as was the custom at the time7. From him, we know that despite long and painful labour, assisted by the “breeder and other female acquaintances”, the newborn daughter has an “appearance of robustness and health”.

Alessandro, a native of Ferrara, had been able to study in times of unimaginable poverty and arrogance, becoming first a clerk in the saltworks of Comacchio, then an inspector in the tobacco field on behalf of the Ministry of Finance of the new unitary state. In his younger years, he had taken part in the Risorgimento campaigns. This experience had marked his thinking and his lifestyle. In the mid-sixties, he was sent to Chiaravalle with duties of superintendence. In the surrounding agricultural area, in addition to olive trees, vines, and wheat, tobacco was cultivated. There was one or perhaps more factories operating in the harvesting, drying of leaves, and preparing of smoking products. Alessandro – with his black moustache and resolute expression, as shown in an old daguerreotype – met Renilde Stoppani in this town. She was originally from Monsanvito8, a small village five kilometres from Chiaravalle, where her father, Raffaele, probably owned some land.

Lively, graceful, of average culture – a rare quality in women of peasant environment – passionate reader, Renilde has in common with her husband a particular Catholic observance and, at the same time, that harmony with the Risorgimento ideals that already denoted a discrete autonomy of thought. Together they will form a modest but decent family not devoid of cultural aspirations.

An unlikely kinship

Renilde had an important surname, the same as the famous abbot Antonio Stoppani, one of the most brilliant scholars at the time. Today, he is considered the father of Italian geology: paleontologist, connoisseur of the Alps (he was among the founders of CAI), particularly of the Brianza and Lecco area. Born in Lecco on August 15, 1824, Stoppani entered the Institute of Charity, the religious congregation founded by Antonio Rosmini, and became a priest in 1848. A few months after his ordination, this choice did not prevent him from participating with other clerics in the Five Days of Milan. On that occasion, he designed hot air balloons – small hot air balloons that, launched from the city, crossed the enemy lines, bringing news of the insurrection to the Lombardy countryside and inciting the rural population to rise. In 1861 he was already teaching at the University of Pavia and at the Polytechnic of Milan. For nine years, from 1883 until his death – which occurred on New Year’s Day in 1891 – he was director of the Civic Museum of Natural History of the Lombard capital, housed in the rooms of Palazzo Dugnani, a historic building located at the centre of the public gardens of Corso Venezia. He wrote a lot: scientific works (reworkings of geology courses that he held in universities, four volumes of palaeontology written in French to spread his studies abroad) and various popular texts. Among these, the best known is undoubtedly Il Bel Paese. Conversazioni sulle belle bellezze naturali, la geologia e la geografia fisica d’Italia (1876) which evoked in its title the suggestive expression used by Dante and Petrarch. The book, intended for young people, was an immediate success and earned him an excellent reputation beyond the narrow scientific circles, making his name popular with families and schools. Deeply religious, Stoppani supported the reasons for free research. Free from confessional preconceptions, whose results did not threaten the credibility of the Holy Scriptures in the spiritual order that they were intended for. Thus were born Il dogma e le scienze positive (1882), Gli intransigenti (1886) and the dense Sulla Cosmogonia mosaica, published in 1887 with a regular imprimatur. He does not mention Darwinian theories, which are far too distant from his horizon of meaning. However, in his books recur the names of Galileo, Newton, and Cuvier, certainly not appreciated by the frowning guardians of Catholic orthodoxy.

The balance shown in addressing the thorny issue of the relationship between science and faith earned him the esteem of Leo XIII, who received him in a private audience in March 1879 to thank him for the volumes the abbot had made him a gift. On that occasion, the Pontiff gave him a gold medal commemorating his pontificate9 and confided to him that he had read with particular interest La purezza del mare e dell’atmosfera fin dai primordi del mondo animato10, a work judged to be “one of the most beautiful […] that came out of the magic pen of Antonio Stoppani”11. It is a text of 1875, still very enjoyable, that skillfully combines scientific interest and popular attitude and formulates hypotheses that modern science has fully demonstrated. This book will fascinate Maria Montessori, as we read in her Antropologia pedagogica. She will take up some of the concepts in Dall’infanzia all’adolescenza and Come educare il potenziale umano (both published in Italy only in 1970). They present innovative didactic proposals to introduce second childhood children to a global (cosmic) vision of the planet. It describes the destructive and constructive forces that run through it and, at the same time, the role of the biosphere, the task of each plant and animal species starting from their body structure, the ability to adapt to the most diverse environments, the care of offspring and food chains for the maintenance of general equilibrium.

It is often asserted that Abbot Stoppani was Renilde’s uncle or even a less close relative, but this is doubtful given his birth in Lecco. Regardless of the geographical coordinates, it is difficult to believe that no objective evidence of this link has been preserved. Already about thirty years ago, the sociologist Nedo Fanelli, then director of the Maria Montessori Study Center of Chiaravalle, undertook a thorough investigation into the family of origin of the illustrious native of the Marches12 without arriving at any conclusive result. However, some continue to give credit to this hypothesis, referring to him, without doubt, as to a maternal uncle of the scientist13 based on a questionable interpretation of what Montessori herself had said. During the Convention of Italian Women held in Milan in 1908, the scientist, addressing a large audience, mentioned an “uncle”… who “when I tried to explain to him the sublime work of spontaneous human development, he would say to me: Don’t tell me about these things, because I feel like going mad”. However, it is hardly credible that a man of science like Stoppani needed to be enlightened by his niece on subjects that must have been much more familiar to him and that he showed such fervent enthusiasm for them. In any case, there is no evidence of a meeting between the abbot and the young Maria.

The paternal family

Thanks to Alessandro’s manuscript and his “memories heard in childhood”, we can reconstruct a family tree that dates back to the early eighteenth century. Four Montessori brothers, possibly natives of Correggio, in the province of Reggio Emilia – “a clergyman, a soldier and two bourgeois” – owned a contract in Ferrara to manufacture tobacco. Of their names, Alessandro remembers only that of Domenico, born in Modena but “progenitor of the Ferrara branch”: his son. The contract for the factory had been stipulated under the pontificate of Clement XIII, therefore, between 1758 and 1769. Domenico, a reckless administrator of the family property, had died suddenly, leaving his children in serious economic difficulties, but their uncles helped them. Giovanni – the only name of the second generation remembered as the writer’s grandfather – was assigned around 1810 a job in the tobacco factory of Ferrara. Married to Artemisia Verdolini, he conceived two sons, both born in Modena: Giulio Cesare and Ercole Nicolò or Nicola (1796-1874). After the death of his first wife, the latter remarried Teresa Donati and went to live with her in Bologna. The grandparents Nicola and Teresa will be the two sàntoli to the baptism of Maria. Nicola’s sons, both from Ferrara, are Giovanni (he will have three children, two girls and a boy, Tito, married to a sick and sterile woman) and Alessandro. He will have only one daughter, Maria. The branch of Ferrara ends here. Therefore, the “noble origins” of which someone speaks14 were totally invented. Alessandro’s list concludes with the sentence: “Maria Montessori born in Chiaravalle in 1870, unmarried. Doctor of Medicine and Professor of Natural Sciences”.

News of his daughter’s childhood is equally scanty, even if collected from birth. On each birthday, the father notes her height: eighty-eight centimetres at three years of age; one meter and nine centimetres at five; one meter and fifty-eight at sixteen. Around seven months old, she says “mama” and “papa”; at eleven, she walks on her own. Between sixteen and nineteen, she can explain what she wants and knows “several names of people, animals and objects”. At two years old, she has already set twenty teeth. A development that is entirely within the norm: a healthy child with vigilant and “modern” parents, as this other note shows:

On 30 April 1871, in the guardroom of the Chiaravalle National Guard, she was inoculated with smallpox by surgeon Dr Arcangeli Adriano, extracting pus from a calf that had been grafted a few days earlier for this purpose. Eight days later, smallpox appeared vigorously in both arms15.

In February 1873, Alessandro was transferred to Florence, where he stayed with his family for about two years. Of this stay in Tuscany, the father tells nothing, except that on 1 October, Maria “began to attend school” – he doesn’t say which one. The parents feared that “because of her lively and independent character”, she wouldn’t be able to get used to it, while the child showed an ability to adapt. On 2 November 1875, the family moved again, from Florence to Rome, because the father had obtained a more prestigious job, and the girl was enrolled in the municipal preparatory school of Rione Ponte, not far from Campo de’ Fiori. On 1 March 1876, Maria entered another municipal school in Via San Nicolò da Tolentino, near Piazza Barberini, thus in an entirely different neighbourhood. It is easy to imagine that the Montessori family had gone to live there. It is the father who mentions this change. It is also possible that they had decided to move to a less popular area of the city and that this very fact had determined the choice of the new school.

A peaceful and protected childhood

What kind of child would Maria Montessori have been? We could perhaps imagine her – also based on her father’s affirmation mentioned above – as a little girl of those in Rome called “peperine”: lively, curious, eager for knowledge. However, the course of elementary school does not seem very bright, partly due to some temporary health problems and long rubella. However, she likes going to school and bonds affectionately with her classmates. She begins to study French and the piano but soon abandons them. Around the age of ten or eleven – as Alessandro tells us – studying began to become a passion for her, sometimes hindered by intense migraines in the evenings. In May 1884, she became a “woman, without suffering serious ailments”.

Among the papers of the Giuliana Sorge Fund, some protocol sheets have been found – fourteen pages covered by very thick handwriting – that Maria wrote between 1904 and 1907, in which she subjects the feelings, desires and disappointments that animated her soul as a young girl to a decidedly merciless analysis. She dwells on her great passion for drama, shown since childhood:

My game was theatre. If I happened to see a play being performed, I imitated it with great vividness: I would invest myself with the parts to the point of paling or sobbing and crying while reciting fantastic things. I invented little comedies and improvised topics; I would improvise clothes and scenes. At school, I did not study at all: studying did not interest me in any of its branches. I never studied the lesson and paid little attention to the teachers by organising games and plays during class time. I was not interested in going on to higher classes.

Thanks to his imagination, she excelled in composition and was able to hide her shortcomings, in grammar or mathematics, for example.

I did not understand arithmetic operations, and for a long time, I wrote down the results by putting fantastic figures, the first ones that came to mind. I wrote well but ‘by ear’, and I could read well: I read with such soul that I made the others cry, and often the teacher would gather several classes to hear me. If there was something to be recited, all it took was a rehearsal, and I was ready to go.

Maria asks her father if she can attend a declamation school for young ladies. He accepts and “sacrifices himself” – exciting much gratitude in her – because he accompanies her there “every evening, even on holidays”16. The teachers of the school congratulate her.

They began to seduce me, making me see that I would have a great future of glory in the theatre. But I also felt it: I was born for it, and that was my passion. By the age of 12, I had made such progress that I was ready to make my theatre debut in the first part. Around me, the teachers were anxious; the schoolmates admired me: I was the centre of their affections […]. This complex seduction of exhortations and successes had a strange effect on my soul: it was only for a moment, and I saw that I was really on my way to glory, provided I removed myself from the seduction of the theatre.

So from one day to the next, she gave up everything, her friendships, her old dreams and gave herself up to “severe studies”, starting with arithmetic. She recognizes as her

characteristic of suddenly abandoning the things to which I seemed most attached – for which I had made even heroic sacrifices […], sudden farewells, sudden escapes, instantaneous changes, complete and utter ruptures, fatal destructions that no one and nothing could remedy […] it was as if all my communication with other humans was suspended, be they the closest family members, the dearest […]. But why do I act this way – so as to make enemies, to make myself detested, while everyone tends to run towards me, to love me, and I feel such deep and boundless love that I can embrace all humanity?

In February 1884, a government school for women opened in Rome – the Regia Scuola Tecnica “Michelangelo Buonarroti”. Maria was among the first ten students to enter, seeming to be passionate about literature. She attends it until 1886, when she obtains, with a vote of 137 out of 16017, “the license and the first-grade prize”.

In another of her rare autobiographical writings, which she titled “La Storia”18,we read:

As a young girl around the age of 14, I went to a boy’s secondary school precisely because there were no other ways open to women other than those of education, which did not appeal to me. So, climbing uncertain paths, I began my studies in mathematics with the primitive intention of becoming an engineer, then a naturalist, and finally, I set about studying medicine.

When she reached the age of sixteen, “she would have liked – her father notes – to enter the high school of women’s education to perfect her literature”. However, according to the regulations in force, only girls from the so-called “Scuola Normale” or those who passed a specific admission test can enter it. She was forced to fall back on the “Istituto Tecnico Maschile Pietro [sic] da Vinci”19, which she attended from 1886 to 1890.

The good results obtained encouraged Maria to pursue her studies and enrol the following autumn in the degree course in Natural Sciences at the Faculty of Physical, Mathematical and Natural Sciences. Likely, this choice was already in keeping with the future plans of the young university student, who must have been aware of the correspondence between the curriculum of the two-year course and that of Medicine and the fact that other women before her had made the transition from one faculty to the other. Indeed, having obtained her diploma in this field in 1892, she asked and obtained the enrollment in Medicine and Surgery.

We don’t know much more about her early years except for a few details about her love life. Her father mentions a young student, older than Maria, who attended the same institute as Maria and began to take an interest in her, “following her from afar”. After some time, he introduced himself to the Montessori family, expressing serious marriage intentions, which could occur “at the imminent end of his studies and after his year of military service”. He is allowed to visit their home once a week on Sundays. At the end of the school year, Maria was promoted, while the young man, who remained in one subject, returned to his village in southern Italy to ask his family’s consent to get engaged. However, his mother believes that it is too early for such an engagement, to the displeasure of Renilde, who likes the young man, but to the relief of Alessandro. While recognizing his good qualities, he was concerned about his character “too dark and melancholy […] too dissimilar from the lively and expansive character of the girl”. Such a contrast could not portend “a happy union between such different beings. Fire to the prophet!” concludes Alessandro. The story ends here without a trace. But Maria, what must she have heard or felt? In those years, the opinion of a daughter, even in a family as open and attentive as hers, was utterly secondary. On the other hand, the prospect of studies must have seemed alluring, full of unknowns and surprises: the time for love was still far away for her.

. Manuscript datable to 1896. A copy is currently in the M. Montessori Archives at AMI.

. Renilde was born in Monsanvito (today Monte Sanvito), in the province of Ancona, on 25 April 1840; Alessandro in Ferrara on 2 August 1832. They married on 7 April 1866 in a double ceremony: civil in the town hall of Monsanvito and ecclesiastical in Chiaravalle. Their portraits are reproduced in Maria Montessori. A Centenary Anthology 1870-1970, AMI, Amsterdam 1970, p. 4. Both died in Rome. She died on 20 December 1912; he died 25 on November 1915. Their tomb is at Verano.

. He emotionally tells his mother about this encounter in a letter of 15 March 1879, reproduced in the Preface that Antonio Malladra affixed to the third edition of the essay that will now take the title of Acqua e Aria. La purezza del mare e dell’atmosfera fin dai primordi del mondo animato, Milano, Cogliati 1898, pp. XVII-XVIII.

. La purezza del mare e dell’atmosfera fin dai primordi del mondo animato, Hoepli, Milan, 1875. This text, the only one by Stoppani to which Maria Montessori refers, is very little known.

. This was written by Alessandro Malladra, a naturalist and professor at the Collegio “Rosmini” in Domodossola, in his preface to thethird edition of the book, published under the new title of Acqua ed aria, ossia la Purezza del Mare e dell’Atmosfera fin dai primordi del Mondo Animato. Conferenze, SEI, Turin, 1898, p. X.

. Today, almost nobody remembers the famous geologist anymore. Until a few years ago, his good-natured effigy was on the packaging of the well-known “Bel Paese” cheese, produced and exported by Galbani worldwide. In 1991, the magazine “il Quaderno Montessori” asked the company the reason for such a combination. It received a prompt and courteous response that we summarize here. In March 1907, at the beginning of his business, Davide Galbani wanted to launch a new type of soft cheese from his dairy in Ballabio, in the province of Como. Wanting to combine it with a famous work – Il Bel Paese – he asked the consent of the abbot’s two nephews. They not only willingly (and free of charge) agreed, but also sent “un ritratto del nostro Zio Abate Stoppani, acciò il Vostro litografo ne tragga le giuste sembianze, bene effigiandolo”. Cf. G. Honegger Fresco (ed.), L’abate Antonio Stoppani, in “il Quaderno Montessori”, xxxii, (2015), no. 127, pp. 55-63, Doc. LXXXIII.

. V.P. Babini-L.Lama, Una «Donna Nuova». Il feminismo scientifico di Maria Montessori, FrancoAngeli, Milano 2000, pp. 35; 78-79.

. Cf. M. Schwegman, Maria Montessori, Il Mulino, Bologna 1999, p. 15.

. The smallpox vaccine was first tested in 1796 by English physician Edward Jenner.

. Curiously, Alessandro never mentions his daughter’s passion in his notes.

. The report card photo with which she is admitted to the second class can be found in A Centenary Anthology, cit., p. 7.

. “La Storia”, an unpublished typescript by Maria Montessori, collected by Lina Olivero, came into my hands thanks to my friend Costanza Buttafava Maggi, a student of Giuliana Sorge and Sofia Cavalletti, head of the Montessori School of Como and today co-director of the one in Via Milazzo in Milan.

. This institute, opened in 1871, was located in the Villa Cesarini at the Esquilino. In 1884 it allowed girls to attend. It seems that Maria was the first pupil. I owe this information to Renilde Montessori.