9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

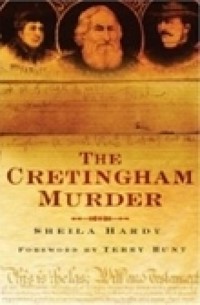

This absorbing collection delves into the villainous deeds that have taken place in Suffolk during the last 200 years. Cases of murder, robbery, child neglect and abuse, and arson are all examined as the shadier side of the county's history is exposed. From the respectable young man who almost severed his mother's head from her body; the brutal murder of a father and daughter that took almost twenty years to solve; and the man who peppered his wife with over fifty gunshot pellets, this book sheds new light on Suffolk's criminal history. Illustrated with a wide range of photographs and archive ephemera, Murder & Crime Suffolk is sure to fascinate both residents and visitors alike as these shocking events of the past are revealed for a new generation.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

For Rachel and Paul.

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Case One Be Sure Your Sins Will Find You Out

The Execution of Edmund Thrower, 1812

Case Two A Most Barbarous Murder

The Shocking Neglect of 6-Year-Old Mary Ann Smith

Case Three A Very Strange Stabbing

The Case of Elizabeth Squirrell

Case Four A Scandalous Wretch

The ‘gross assault’ of 13-Year-Old Henrietta Ship

Case Five Arson at Laxfield

The Trial of Robert Goddard, 1856

Case Six At the End of his Tether

The Case of William Bear

Case Seven The Lost Sheep

Sheep Stealing at Elmswell

Case Eight Flint-Hearted

A Case of Excessive Drinking in George Street, Brandon

Case Nine Murder at Rose Cottage

The Case of a Criminal Lunatic

Case Ten A Nineteenth-Century Jobsworth

The Acquittal of John and Sarah Starling

Case Eleven The Brown Paper Parcel

The Reprieve of Ada Brown

Sources

Also by the Author

Copyright

Acknowledgements

As always, this work could not have been completed without help, so my very sincere thanks go to: David Burnett of the Sudbury Museum and Heritage Centre, who so readily gave his expert knowledge and offered the use of illustrations; Steve Williams, who also took trouble to search out and supply suitable background photographs of Stowmarket; Berkshire Record Office, which kindly provided the information about Broadmoor Hospital; the Suffolk Record Office, which again made many documents available to my most valuable researcher, Rachel Field – without her, much of the painstaking detail about the lives of some of those mentioned herein would have been lacking. My debt to her is enormous. As it is to Michael, who not only ferried me around the countryside to visit the locations of the various crimes mentioned, but also took many of the photographs and listened to me as I speculated on the various cases I have uncovered.

Introduction

‘I really do not understand the public’s obsession with crimes of the past!’ You could almost hear the woman in the bookshop’s sniff of disapproval. Then, perhaps remembering this might not be quite the remark to make to the author of such a volume, she conceded, ‘I much prefer your proper history books.’

Fortunately, another ‘obsessive’ appeared with one of the offending books for me to sign, so I was saved having to explain that these true crime accounts are indeed the very stuff of real social history. It is through recording what went on in criminal trials during the eighteenth and nineteen centuries that we learn a great deal more about the everyday life of our ancestors than any history textbook can tell us. Instead of generalisations about the state of the country, we get to see real people from all walks of life, their lives exposed in court as they account for whatever crime they were accused of committing. But it is not just the prisoner who is the focus of our attention; the witnesses who are called to testify to the guilt or defence of the prisoner also shed light on aspects of daily life. Thus we learn, for example, about housing conditions – which give such intimate details as sleeping arrangements in crowded homes with their very basic toilet facilities. And with these details, we can trace the improvements both in building and hygiene as the centuries progressed.

Each of the accounts in this book has been chosen not just because it was an eye-catching case, but also for what it tells us about the attitudes prevailing at the time. We are brought face-to-face with the stark reality of acute poverty among working families, which could result in the man of the house being driven to crime in order to feed his children. But we also see that the effects of worry and over-exertion could lead to ill-treatment of wives and terrible cruelty to children.

These accounts also remind us of the status of women at that time. A married woman was unable to act in her own right; in one case, it was mentioned in passing that a woman had been left a small inheritance but could not receive it without her (missing) husband’s signature on the document, while in another case a mother was told that her husband, not she, must seek the required document necessary for Poor Law assistance.

The dreaded Poor Law crops up in many of the cases. By the mid-nineteenth century, the problem of financing the system had become so acute that it was necessary to make cuts wherever possible. Where once it had been the norm for a man to apply for, and receive, assistance to help his family over a difficult period, with the understanding that the loan would be paid back when possible, outdoor relief, as it was known, was now almost impossible to claim. Instead, the whole family was sent to the workhouse, where those who were able to would work until they earned sufficient money to eventually release the family. The stigma of having to resort to the workhouse grew at this time, leading many to turn to crime rather than face that prospect. Often those who had no other alternative were young, pregnant women. It had become increasingly difficult as the century progressed to track down putative fathers and present them with orders to pay towards their child’s upkeep.

The opening up of the railways and the prospect of employment elsewhere, led many men to move away rather than accept their responsibilities. The courts regularly dealt with cases of girls, usually servants, who, having managed to hide their state from their employers, then gave birth in secret. Horrible details emerged of girls deliberately strangling the child and then hiding the body – in one case, this was done in the fire space under the copper. Girls who had no other option went into the workhouse to have their babies and stayed for the first few months with their child, before leaving to take up employment.

Two further types of crime dominate the press accounts in the second half of the nineteenth century. One had its roots in the industrialisation of agriculture, bringing labourers the very real fear that they would be replaced by machines. They thought the only way they could take reprisals against their employers was by setting fire to farm buildings and valuable grain stores.

The second type of crime was rape, and here we get an example of double standards. Where the case involved a grown woman, it becomes apparent that more often than not the jury took the view that she was a willing participant, and the man would get off. Consequently many cases were never reported. However, it was a different story when the plaintiff was a girl of thirteen or under. During the Victorian era, there had grown almost a cult surrounding the sanctity of childhood. That was fine for the middle classes upwards, but among the labouring classes, girls of twelve and thirteen were in many cases already working, many as maids in middle class households. When a learned judge expounded his disgust at hearing of the rape of a barely teenage girl – calling her a mere child – he was overlooking the fact that many of her compatriots were adding to the growing number of prostitutes in the towns and cities.

We tend nowadays to accuse the Victorians of double standards, but there is no doubt that there was a deep concern about the laxity of moral standards generally. Spurred on by social reformers, both within and outside the Church, Parliament was forced to take measures to improve life for those most in need. Foremost in this was the desire that everyone should be literate – brought about by the introduction of compulsory elementary education. In urban areas, new housing developments replaced overcrowded unsanitary courts, introducing better living standards; but, in spite of the efforts of the Temperance societies and the Salvation Army, the demon drink had yet to be beaten. Cheap alcohol and strong beer filled an empty stomach and temporarily blotted out problems, but in some it led to a loss of control leading to abusive behaviour within the family and crime outside it; unprovoked fights and muggings could, in turn, lead to murder.

Selecting the items for this collection has been a voyage of discovery. We tend to think of Suffolk as a purely rural area engaged in raising food, both crops and animals, to feed the country as a whole, with the port of Ipswich dispatching cargo bound for other British ports and across the continent. Ipswich also had a varied industrial manufacturing scene. Those who remember being taught about the canal system and its importance to the Industrial Revolution can have no better example of its impact on Suffolk than in Stowmarket, where the opening of a navigable system led to a number of flourishing businesses – including the factory producing explosives. Sudbury too had its fair share of industry, mainly of course the silk factories, but who would have thought there was once also a flourishing crayon factory there?

Similarly, I was surprised to learn that Brandon was not just famous for the manufacture of the flints, providing the essential component of the flintlock guns which contributed greatly to England’s success against the French at Waterloo, but was also once the greatest provider in the country of felt made from rabbit fur, used to make hats. The occupation ‘furrier’, which appeared on a Brandon census form, was a profession of which I had no previous knowledge. Similarly, that magnificent opening scene from the film adaptation of Dickens’ Great Expectations becomes very real when you read about the Suffolk men who spent years serving in prison hulks in Portsmouth harbour. It is also amusing to read about the development of the railway system in Suffolk, even when we learn that over 120 years ago, a gentleman’s arrival in Ipswich was delayed because the line was blocked at Ilford!

Sheila Hardy, 2012

Case One

Be Sure Your Sins Will Find You Out

The Execution of Edmund Thrower, 1812

It may come as a surprise to discover that even 200 years ago, the perpetrators of unsolved crimes, or ‘cold cases’ as we now know them, could be brought to justice almost twenty years after the event. Without the aid of forensic science and all the sophisticated means available to the modern police service, it was often the chance remark, a casual conversation about something else entirely, or the revelation of information of a confidante, that finally brought a criminal to the gallows.

It was on the evening of Wednesday, 16 October 1793 that Thomas Carter and his daughter Elizabeth, who kept the village shop in Cratfield, were last seen alive. John Wright of Stradbroke saw them at around six o’clock walking in the garden as he passed their cottage on his way home. Some three hours later, their near neighbour Sarah Dunnet, being worried that her clock was a bit slow, decided she would go along the road to get a time check from the Carters. She didn’t go right up to the door because, seeing that their lights were extinguished and all was quiet within the house, she assumed they had retired for the night. It was a crisp, bright, moonlit night and near to nine o’clock when John Harman and his wife, returning by cart from a day in Norwich, crossed Chevenhall Green, close to the road where the Carters lived, and heard what could have been a woman scream. John remarked to his wife that he was sure it was a female shriek he had heard, to which Mrs Harman replied that no doubt it was a domestic quarrel involving a man throwing his wife out of doors. And if that was the case, the least they had to do with it the better. However, when a bit further on the cart reached the intersection of four ways, one of which led to the Carters’ home, John was convinced that he saw a man just a bit shorter than his own height of 5 feet 6 inches who, if not actually running away, was certainly walking very quickly.

The following morning, it was Mrs Dunnet who made the horrific discovery of Elizabeth’s body; it had been flung half on and half off the gooseberry bushes which skirted the garden. She was joined almost immediately by John Wright whose usual path to work took him past the Carters’ home, and together they stared at the grisly sight – hardly able to comprehend Elizabeth’s shattered head and the scattered remnants of the contents of her skull. Almost in a trance, John entered the house, concerned for the old man and there he was confronted with Thomas, still seated in his armchair but with his head stove in.

At the coroner’s inquest Mrs Dunnet, John Harman and John Wright reported what they had seen and heard, and further information was given by others that a male stranger had been spotted, lurking in different parts of the village throughout Wednesday afternoon and evening. Together they built up a picture of his appearance. He had worn a light-coloured, long coat over a black or dark waistcoat and breeches, and his stockings were described as speckled. His brown hair was plaited and tied up with a black ribbon, topped with a large, round flat hat. Another witness swore that he had seen a person answering this description running very fast in the road leading from the Carters’ house towards Cratfield Bell Green at about nine o’clock that evening. It must have been Wright who testified that he too had seen a stranger talking to the Carters at their gate at six o’clock. But he identified his stranger as a woman, dressed in a coloured jacket, a blue petticoat – that is an overskirt – and a black bonnet. Recording that the Carters had been murdered by person or persons unknown, the inquest was adjourned until Monday 11 November, in the hope of gathering further information. A request for other witnesses, who had not come forward so far, to speak to the churchwardens, the Overseers of the Poor Law or the village constables, seems to have been fruitless and the local press did not even bother to report on the adjourned inquest, if indeed it was actually held.

Understandably the case provoked great alarm in the vicinity at the time for there seemed to be no motive for two such vicious attacks. Nothing within the house had been disturbed; there was no sign of attempted robbery. One or two had come under suspicion but no charges were made and eventually the case became buried in obscurity. That is until eight or nine years had passed, when John Head found himself in Norwich gaol in the summer of 1801. Awaiting execution for the theft of two heifers was John Saunders, who told Head that he had in the past been suspected of the Carters’ murder, which he had always hotly denied, but he said he did know how the murders had been committed and who was responsible. Following Saunders’ execution, Head had asked the Governor of the gaol for permission to speak to a magistrate as he had valuable information to impart. Archdeacon Oldershaw duly came to the gaol with a constable to take Head’s deposition about a murder which had taken place several years earlier. He not only named the murderer as one Edmund Thrower, but also gave a number of details leading up to the crime and how it was carried out. Quite why the Archdeacon did nothing about this deposition at the time is not clear. Certainly when the written deposition was required some twelve years later as material evidence, it could not be found.

Yet the information must have remained at the back of the Archdeacon’s mind, and it was he who may have been responsible for finally bringing the culprit to justice. In December 1811, the country had been rocked by the horror of what became known as the Ratcliffe Highway murders. Briefly, on the 7 December, a young shopkeeper called Marr, his wife, small baby and shop boy were all discovered brutally murdered. Robbery certainly had not been the motive and there seemed to be no other. Twelve days later, in the same road John Williamson, a 59-year-old publican, his wife and a servant were found dead in very similar circumstances. Just after this second murder, the Archdeacon, discussing the events in London with Mr Fox, an attorney, remarked that they bore some similarity to the murders in Cratfield in 1793. During the conversation he mentioned his being asked to visit Head in Norwich gaol and described how he had accused a man named Thrower. Mr Fox seized on the name, saying it was a strange coincidence but he had a legacy for a woman of that name. He had been unable to pay it to her because he needed her husband’s permission to do so and, so far, they hadn’t been able to find him. Oldershaw, on his return to Norfolk, eventually tracked down Thrower, who was living and working as a blacksmith in the village of Carbrook.

Thrower was arrested and brought before the magistrates in Harleston at the beginning of January 1812. Honour may be said to exist among thieves but when the life of one is at stake and one can escape by implicating the other, no such code exists. Thrower, swearing his own innocence, immediately named Head as the culprit, aided and abetted by another criminal known as Gypsy William Smith. These two were then arrested as well and accused along with Thrower of the murder of Elizabeth and Thomas Carter. None of them had led blameless lives; each had been in and out of prison and two of them at least had served a seven-year term of transportation.

John Head, who realised that the sentence for this particular charge was death, saw the opportunity to save his own skin by turning King’s evidence against his fellow criminal and erstwhile friend. So on 20 March 1812, he was brought under guard from Ipswich gaol to the Suffolk Assizes held at Bury St Edmunds. It was there that his evidence as an ‘approver’ – as it was known – sealed the fate of Edmund Thrower.