16,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

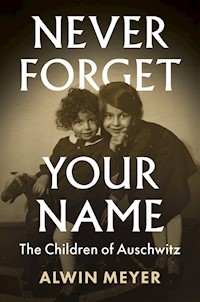

The children of Auschwitz: this is the darkest spot in the ocean of suffering that was the Holocaust. They were deported to the concentration camp with their families, with most being murdered in the gas chambers upon their arrival, or were born there under unimaginable circumstances. While 232,000 children and juveniles were deported to Auschwitz, only 750 were liberated in the death camp at the end of January 1945. Most of them were under 15 years of age. Alwin Meyer's masterwork is the culmination of decades of research and interviews with the children and their descendants, sensitively reconstructing their stories before, during and after Auschwitz.

The camp would remain with them throughout their lives: on their forearms, as a tattooed number, and in their minds, in the memory of heart-rending separation from parents and siblings, medical experiments, abject confusion, ceaseless hunger and a perpetual longing for home and security. Once the purported liberation came, there was no blueprint for piecing together personal biographies after the unthinkable had happened. Many of the children, often orphaned, had forgotten their names or ages, and had only fragmented understandings of where they came from. While some struggled to reconnect to the parents from whom they had been separated, others had known nothing other than the camp. Some children grew up without the ability to trust and to play. Survival is not yet life – it is an in-between stage which requires individuals to learn how to live. The liberated children had to learn how to be young again in order to grow into adults like others did.

This remarkable book tells the stories of the most vulnerable victims of the Nazis’ systematic attempt to extinguish innocent lives, and rescues their voices from historical oblivion. It is a unique testimony to the horrific suffering endured by millions in humanity’s darkest hour.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 1064

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

Preface

Notes

Acknowledgements

Life Before

Notes

‘That’s When My Childhood Ended’

Notes

‘The Hunt for Jews Began’

Notes

Gateway to Death

Notes

‘As If in a Coffin’

Notes

Oświęcim – Oshpitzin – Auschwitz

Notes

Children of Many Languages

Notes

Small Children, Mothers and Grandmothers

Notes

‘Di 600 Inglekh’ and Other Manuscripts Found in Auschwitz

Notes

Births in Auschwitz

Notes

‘Twins! Where Are the Twins?’

Notes

‘To Be Free at Last!’

Notes

Transports, Death Marches and Other Camps

Notes

Dying? What’s That?

Notes

Alive Again!

Notes

Who Am I?

Notes

‘… The Other Train Is Always There’

Notes

Note on the Interviews

Index

Plates

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

iii

iv

v

vi

ix

x

xi

xii

xiii

xiv

xv

xvi

xvii

xviii

xix

xx

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

322

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

334

335

336

337

338

339

340

341

342

343

344

345

346

347

348

349

350

351

352

353

354

355

356

357

358

359

360

361

362

363

364

365

366

367

368

369

370

371

372

373

374

375

376

377

378

379

380

381

382

383

384

385

386

387

388

389

390

391

392

393

394

395

396

397

398

399

400

401

402

403

404

405

406

407

408

409

410

411

412

413

414

415

416

417

418

419

420

421

422

423

424

425

426

427

428

429

430

431

432

433

434

435

436

437

438

439

440

494

495

496

497

498

499

500

501

502

503

504

505

506

507

508

509

510

511

512

513

514

515

516

517

518

519

520

521

521

522

523

524

525

526

527

528

529

530

531

532

533

534

535

536

537

538

539

540

541

542

543

544

545

546

547

548

549

550

551

552

553

554

555

556

557

558

559

560

561

562

563

564

565

566

567

568

569

570

571

572

573

574

575

576

577

578

579

580

581

582

583

584

585

586

587

588

589

590

591

592

593

594

595

NEVER FORGET YOUR NAME

The Children of Auschwitz

Alwin Meyer

Translated by Nick Somers

polity

Copyright Page

Originally published in German as Vergiss deinen Namen nicht. Die Kinder von Auschwitz by Alwin Meyer

© Steidl Verlag, Göttingen 2015

This English edition © Polity Press, 2022

The translation of this work was funded by Geisteswissenschaften International – Translation Funding for Work in the Humanities and Social Sciences from Germany, a joint initiative of the Fritz Thyssen Foundation, the German Federal Foreign Office, the collecting society VG WORT and the Börsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels (German Publishers & Booksellers Association).

The publishers gratefully acknowledge Catriona Corke’s contribution to the English translation.

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

101 Station Landing

Suite 300

Medford, MA 02155, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-4550-6

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021941498

by Fakenham Prepress Solutions, Fakenham, Norfolk NR21 8NL

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Dedication

This book is dedicated to Janek (Jack) Mandelbaum, without whose generosity the English translation would not have been possible. Having survived five Nazi concentration camps and the murder of his parents, sister and brother during the Holocaust, he has spent the last seventy-five years educating people about this dark period of history. His contribution to the publication of this book is part of that noble effort.

Preface

Children in Auschwitz: the darkest spot on an ocean of suffering, criminality and death with a thousand faces – humiliation; contempt; harassment; persecution; fanatical racism; transports; lice; rats; diseases; epidemics; beatings; Mengele; experiments; smoking crematorium chimneys; abominable stench; starvation; selections; brutal separation from mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, grandmothers, grandfathers, aunts, uncles and friends; gas …

In 1940, a first camp by the name of Auschwitz, later to be known as the Main Camp or Auschwitz I, was erected by the Nazis on the outskirts of the Polish town of Oświęcim (65 kilometres west of Kraków). The first transport of Polish inmates arrived from German-occupied Poland in mid-1940. In 1941, the Nazis planned and built the killing centre (extermination camp) Auschwitz-Birkenau, also known as Auschwitz II, on the site of the destroyed village of Brzezinka.

From March 1942, Jewish children and their families were transported to Auschwitz from almost all German-occupied countries, for the sole reason that they were Jews. There were already a large number of Jewish boys and girls in the first transports to Auschwitz from Slovakia. Well over 200,000 children were to follow, and almost all of them were murdered.

The Auschwitz complex consisted of forty-eight concentration and extermination camps. Auschwitz-Birkenau has become the unmatched symbol of contempt for humanity, and a unique synonym for the mass murder of European Jewry. It was the site of the largest killing centre conceived, built and operated by the Germans, and played a central role in the Nazi ‘Final Solution’,1 the systematic extermination of Europe’s Jewish inhabitants.

By far the largest group of children deported to Auschwitz were thus Jewish girls and boys (see also pages xi and xii). Most of them were transported with their families in packed, closed and sealed freight cars, mercilessly exposed to the summer heat and freezing winters. They had to relieve themselves in buckets that were soon full. Because the wagons were so packed, many couldn’t even reach the buckets in time and the floors were swimming in urine and excrement. The stench was overwhelming. In many cases, the deportees had little or nothing to eat or drink. Although especially the small children begged constantly for water, their entreaties went unheard. Many – particularly infants, young children and elderly persons – died during the journeys, which often lasted for days.

The Jews were deliberately kept in the dark about the real intentions of the Nazis. Before the deportations, they were told that they were being resettled in labour camps in the East, where they could start a new life.

The opposite was true. The Jewish children, women and men were destined to be murdered. They were ‘welcomed at the ramp in Auschwitz with the bellowed order: “Everyone out! Leave your luggage where it is!”’ The few people who were initially kept alive never again saw the possessions they had been allowed to bring with them.

Selections began sporadically from April 1942, and then regularly from July of that year. They were carried out on the railway ramp, usually by SS doctors but also by pharmacists, medical orderlies and dentists. Young, healthy and strong women and men whom they considered ‘fit for work’ were temporarily allowed to live and were separated from the old and invalid, pregnant women and children. Germans randomly classed around 80 per cent of the Jews – often also entire transports – as ‘unfit for work’, particularly during the deportations to the Auschwitz-Birkenau killing centre of 438,000 Hungarian Jewish children, women and men from May 1944. These people were marched under guard or transported in trucks by the SS to one of the crematoria, where they were ordered to undress. Under the pretext that they were to be showered, the SS herded them into the gas chambers disguised to look like showers. The poisonous gas Zyklon B was then introduced, and those inside suffered an agonizing death by suffocation. It took 10 to 20 minutes for them all to die.

Small children in Auschwitz were almost all killed on arrival. If a mother was carrying her child during the initial selection, they were both gassed, however healthy and ‘fit for work’ the young mother might be. This was irrelevant. Pregnant woman also suffered a terrible fate in Auschwitz. They were ‘automatically’ killed by phenolin injection, gassed or beaten to death. This applied initially to Jewish and non-Jewish women alike. Pregnant women from other concentration camps were also transferred to Auschwitz exclusively to be gassed.

A stay of execution was granted only to those condemned to heavy physical slave labour inside and outside the camp. These men and women were physically and psychologically exploited in road building, agriculture or industrial and armaments factories, in which inmates from the satellite camps in particular were forced into slave labour.

Sometimes children aged between 13 and 15 were also ‘selected for work’ and allowed to live, usually only for a short time. For example, a large group of children and juveniles were assigned to the ‘Rollwagen-Kommando’, where they pulled heavy carts in place of horses, transporting blankets, wood or the ashes of incinerated children, women and men from the crematoria. They were highly mobile and had plenty of opportunity to see the atrocities taking place in the camp.

Some sets of twins up to the age of 16 were also kept alive for a time. SS doctor Mengele exploited and misused both Jewish and Sinti and Roma twins for pseudo-medical experiments. They were selected, measured, X-rayed, infected with viruses or had their eyes cauterized, and then killed, dissected and burned.

Throughout the five years of its existence – from the first to the last – however, the main purpose and primary aim of the killing centre was extermination. All other aims by the Nazis – such as exploitation of the children, women and men as slave labourers, or the criminal, so-called ‘medical’, experiments by SS doctors – were of secondary importance.

The children and juveniles transferred temporarily to the camp soon became acquainted with the reality of Auschwitz. They didn’t know whether they would still be alive from one day to the next. No one could foresee how the same situation would be dealt with by the SS the next day, the next hour or the next minute. Any act could mean immediate death. Apart from extermination, nothing in Auschwitz was predictable. The children were permanently confronted with death and knew that they had to be on their guard at all times.

*

More than 1.3 million people were deported to Auschwitz between 1940 and 1945. Among them were at least 1.1 million Jews. They came from Hungary, Poland, France, the Netherlands, Greece, Czechoslovakia, Belgium, Romania, the Soviet Union (especially Byelorussia, Ukraine and Russia), Yugoslavia, Italy, Norway, Luxembourg, Lithuania, Latvia, Austria, Germany and elsewhere.

2

The Auschwitz complex consisted of three main units. The Main Camp, Auschwitz I, held up to 20,000 people. The killing centre Birkenau, or Auschwitz II, was the largest unit of the camp complex, containing as many as 90,000 children, women and men. Birkenau was divided into ten sections separated by electrified barbed-wire fences. For example, there was the Women’s Camp, the Theresienstadt Family Camp, the Men’s Camp and the Gypsy Family Camp, where Sinti and Roma were interned. In Auschwitz III (Monowitz), IG Farbenindustrie AG (headquarters Frankfurt am Main) employed Auschwitz concentration camp inmates as slave labour to make synthetic rubber (‘Buna’) and fuel. There were also forty-five satellite camps of various sizes, such as Blechhammer, Kattowitz or Rajsko.

3

At least 1 million Jewish babies, children, juveniles, women and men, mostly in Auschwitz-Birkenau, were starved to death, killed by injections into the heart, murdered in criminal pseudo-medical experiments, shot, beaten to death or gassed.

4

Between 70,000 and 75,000 non-Jewish Poles, 21,000 Roma and Sinti, 14,000 Soviet prisoners of war and 10–15,000 non-Jewish inmates speaking many languages were murdered in Auschwitz.

5

At least 232,000 infants, children and adolescents between the ages of 1 day and 17 years inclusive were deported to Auschwitz, including 216,300 Jews and 11,000 Roma and Sinti; 3,120 were non-Jewish Poles, 1,140 were Byelorussians, Russians and Ukrainians, from other nations.

6

On 27 January 1945, only about 750 children and youths aged under 18 years were liberated; only 521 boys and girls aged 14 and under,

7

including around 60 new-born babies, were still alive, and several of them died shortly afterwards.

8

*

Very few of the children deported to Auschwitz remained alive. To some extent, the survival of every child was an anomaly unforeseen by the Nazis, a type of resistance to the only fate that Germans had planned for the children – namely, extermination. Very many of the children and juveniles in this book are fully aware that their survival was a matter of pure luck.

In some cases, comradeship and solidarity among the camp inmates helped them to stay alive. For example, some women relate how their pregnancy remained undetected because of the starvation rations in the camp, enabling them to give birth in secret. Once the child was born, it had practically no chance of survival. SS doctors, medical orderlies and their assistants took the mother and child and killed them. Sometimes, however, the mother managed, with the aid of other women inmates, to hide and feed her baby for a while. This was particularly true of the infants born in the last weeks and days before Auschwitz-Birkenau was liberated.9

Others are convinced that they survived through their belief in God. Otto Klein, who, at the age of 11, was claimed with his twin brother Ferenc by Mengele for pseudo-medical experiments, for example, never dared to doubt in God. ‘That would have been the end. Deep down in my heart, I always remained a Jew. No one and nothing could beat that out of me. Not even Auschwitz.’

For the few children who were liberated, the pain is always there: before breakfast, during the day, in the evening, at night. The memory of mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, the grandparents, girlfriends, boyfriends, aunts and uncles, killed in the camps. For a lifetime and beyond, the pain is ever present, not only in their lives but also in those of their own children and grandchildren.

Even if the number tattooed on the forearm, thigh or buttocks is often the only outward sign that they were in Auschwitz, they bear the traces of suffering on their bodies and in their souls.

The older liberated children of Auschwitz talk about their happy childhoods at home, about school, life in a Jewish community, the relationship between Jewish and non-Jewish children, the arrival of the Germans, the growing apprehension, the refugees, the chaos prior to deportation, the end of playing, the transport in cattle wagons, the arrival in Auschwitz, the mortal fear.

The children remember the gnawing hunger; the experiments carried out on them; the cold that pierced to the bone; the constant selections by the SS; the fear that their number would be called out; the longing for their parents, a good meal, an eiderdown, warmth. They were torn between despair and hope. They wanted to see their mothers and fathers, brothers and sisters again. They wanted to go home. They wanted their old and happy lives back. They wanted to be able to be children again.

Only a few survived Auschwitz and the other camps where they were interned. The children rescued from the camps were just skin and bone. The people caring for them feared that they would not live. They looked like skeletons, with bite wounds from the dogs, bodies covered in sores, eyes stuck together with pus; for a long time, anything they ate went in one end and straight out the other; they had tuberculosis, pneumonia and encephalitis.

Some had no idea where they were from. Practically all of them were orphans. The smaller children in particular were marked by their life in the camp. They spoke a mixture of languages. For a long time, the girls and boys lived in fear that something – particularly food and clothing – would be snatched away from them. Hiding food was part of their survival strategy. They defended it with their lives, because in the camp even the smallest possession had had inestimable value. Every small piece of bread meant survival for one or two days or more. Even spoiled food was not thrown away. When adults who had not been in the camp suggested this, they would look at them incredulously and think to themselves: ‘You have no idea what life is really like!’

The small children were incapable of playing. When they were presented with playthings, they gave them a cursory glance or threw them away. They didn’t know what they were or what to do with them. These children had first to learn how to play. They were irritable and mistrustful. Dogs, rats and uniforms caused indescribable anxiety. When someone left them, some of the smaller children assumed they were dead. Others couldn’t believe at first that people could die of natural causes.

The children of Auschwitz were free, but how could they live after what they had been through? It took them years of painstaking work to learn to see life from a perspective other than that of the camp. They had to learn to survive the camp emotionally. They had to learn to be young again so as to be able to grow old like others.

As they grew older, those children of Auschwitz were increasingly motivated to find out where they came from. In searching for their parents, the number tattooed on their arm often helped, because their numbers were tattooed at the same time – first the mother, then the daughter with serial numbers from the Women’s Camp; or the father, then the son, from the Men’s Camp.

Only a few were reunited, years later, with their parents. They were soon conflicted as to who their real mothers and fathers were. In the experience of the author of this book, the answer was always the adoptive parents. They went back to the place where they had experienced most warmth in their lives. For the biological parents, this was a bitter disappointment, losing a son or a daughter for a second time. The others never stopped asking whether their families had been killed in the gas chambers, or had perhaps survived somewhere. They continued to look for their parents, siblings, grandparents and friends – at least in their dreams.

Those who survived Auschwitz as children or juveniles continued to wonder whether their families had really died in the gas chambers. They would come across newspaper articles reporting on the return of people thought dead. Hope made it possible for them to continue living. It was just a dream that they would wake from. Then everything would be fine again. But no one came back.

The survivors’ children and grandchildren can sense how their parents and grandparents suffer. They often know much more than their parents and grandparents think – despite their having done everything possible to protect them from the consequences of Auschwitz.

The children of Auschwitz had to show supreme resolve to make their way in the world. They sought and found new lives, went to school, studied, married, had children, pursued careers and created new homes. But as they got older and no longer had to concern themselves as much with their own families, the memories of Auschwitz returned with a vengeance. Every day, every hour, the pain is there: the memory of their mothers, fathers, brothers and sisters, all murdered. Many can still remember them quite clearly. How they would love to hear their voices again. How they would love once again to speak to their parents and siblings, or to hug them.

The ancestors and descendants of the children of Auschwitz who tell their stories in this book lived and live among us in Będzin, Békéscsaba, Berlin, Bilky, Budapest, Csepel, Czaniec, Davos, Delvin, Dimona, El Paso, Esslingen, Frankfurt am Main, Gdynia, Geneva, Givat Haviva, Haifa, Hajdúböszörmény, Hartford, Herzliya, Hronov, Jerusalem, Kansas City, Kaunas, Konstanz, Kraków, Kutná Hora, London, Los Angeles, Lubin, Miskolc, Montreal, Mukachevo, Naples, New York, Odolice, Orsha, Oslo, Ostrava, Paris, Prague, Providence, Sárospatak, Thessaloniki, Topol’čany, Toronto, Turany nad Ondavou, Vel’ký Meder, Vienna, Vilnius, Vitebsk, Warsaw, Yad Hanna, Yalta, Yenakiieve, Zabrze, Zurich.

When the persecutions by Nazi Germany began throughout Europe, the children of Auschwitz featured in this book were babies, toddlers and children up to 14 years old. When they were forced to work as slaves or were interned for the first time in ghettos or camps, they were all children. When they were transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau, four were juveniles, none of the others older than 15. Four of the children were born in Auschwitz.

The children of Auschwitz interviewed for this book are among the very last survivors. Herbert Adler, Yehuda Bacon, Halina Birenbaum, Robert Büchler, Gábor Hirsch, Lydia Holznerová, Krzysztof J., Otto Klein, Kola Klimczyk, Josif Konvoj, Eduard Kornfeld, Heinz Salvator Kounio, Géza Kozma, Ewa Krcz-Siezka, Vera Kriegel, Dagmar Lieblová, Dasha Lewin, Channa Loewenstein, Israel Loewenstein, Mirjam M., Jack Mandelbaum, Angela Orosz-Richt, Lidia Rydzikowska, Olga Solomon, Jiří Steiner, William Wermuth, Barbara Wesołowska and other children of Auschwitz were willing to tell the story of their survival, and life afterwards.

The life stories of the children of Auschwitz are based above all on numerous lengthy interviews with them, their families and friends. This book could never have been written without the willingness of the children of Auschwitz to provide information, without their hospitality, their openness and their trust. It is their book first and foremost. It contains the life stories of people who know more than others what life means.

Notes

Apart from the interviews above, there were numerous other unrecorded interviews with the children of Auschwitz and their families. All interviewees also made records, letters, documents and photos available. The interviews and personal documents and correspondence (letters, emails and telephone calls) are not generally mentioned specifically in the notes. The following sources were also used.

(All translations are by Nick Somers, unless otherwise marked.)

1

See, in particular, Raul Hilberg,

The Destruction of the European Jews

(Chicago 1961), and Götz Aly, ‘

Endlösung’ – Völkerverschiebung und Mord an den europäischen Juden

(Frankfurt am Main 2017).

2

Franciszek Piper, ‘Mass Murder’, in Wacław Długoborski and Franciszek Piper, eds.,

Auschwitz 1940–1945: Central Issues in the History of the Camp

, vols. I–V, trans. from Polish by William Brand (Oświęcim 2000), vol. III, pp. 11–52, 205–31; Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum (Teresa Świebocka, Jadwiga Pinderska-Lech and Jarko Mensfelt),

Auschwitz-Birkenau: The Past and the Present

(Oświęcim 2016), pp. 6–12.

3

Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum,

Auschwitz-Birkenau

.

4

Piper, ‘Mass Murder’; moreover, from the first day of occupation onwards, Jews were ruthlessly murdered in the countries invaded by Nazi Germany, by German ‘Einsatzgruppen’ and ‘Einsatzkommandos’ (mobile killing units), but also by Wehrmacht units. According to the United States Holocaust Museum, 1.3 million Jews were shot by Wehrmacht and SS units or killed in gas trucks on the territory of the former Soviet Union alone: United States Holocaust Museum, Documenting Numbers of Victims of the Holocaust and Nazi Persecution | The Holocaust Encyclopedia (

ushmm.org

).

5

Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum,

Auschwitz-Birkenau

, p. 12 (prepared by Piper).

6

Helena Kubica,

Geraubte Kindheit – In Auschwitz befreite Kinder

[Stolen Childhood: Children Liberated in Auschwitz] (Oświęcim, October 2021), pp. 7, 59. Altogether, 400,000 babies, children and women were registered in Auschwitz, including over 23,500 children and juveniles, almost all of whom were murdered.

7

Ibid., pp. 17, 33, 64.

8

Helena Kubica,

Pregnant Women and Children in Auschwitz

(Oświęcim 2010), p. 13; see also George M. Weisz and Konrad Kwiet, ‘Managing Pregnancy in Nazi Concentration Camps: The Role of Two Jewish Doctors’, in

Rambam Maimonides Medical Journal

(Israel), 9.3 (July 2018).

9

Alwin Meyer,

Mama, ich höre dich – Mütter, Kinder und Geburten in Auschwitz

(Göttingen 2021), pp. 104–62.

Acknowledgements

This book could not have been written without the cooperation and willingness to provide information of the following:

Herbert Adler, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Yehuda Bacon, Jerusalem, Israel

Halina Birenbaum, Herzliya, Israel

Robert Büchler, Lahavot Haviva, Israel

Gábor Hirsch, Esslingen, Switzerland

Lydia Holznerová, Prague, Czech Republic

Krzysztof J., Poland and Germany

Otto Klein, Geneva, Switzerland

Kola Klimczyk, Kraków, Poland

Josif Konvoj, Vilnius, Lithuania

Eduard Kornfeld, Zurich, Switzerland

Heinz Salvator Kounio, Thessaloniki, Greece

Géza Kozma, Budapest, Hungary

Ewa Krcz-Siezka, Poland

Vera Kriegel, Dimona, Israel

Dasha Lewin, Los Angeles, USA

Dagmar Lieblová, Prague, Czech Republic

Channa Loewenstein, Yad Hanna, Israel

Israel Loewenstein, Yad Hanna, Israel

Mirjam M., Tel Aviv, Israel

Jack Mandelbaum, Naples, FL, USA

Angela Orosz-Richt, Montreal, Canada

Hanka Paszko, Katowice, Poland

Anna Polshchikova, Yalta, Ukraine

Lidia Rydzikowska-Maksymowicz, Kraków, Poland

Adolph Smajovich-Goldenberg, Bilky, Ukraine

Olga Solomon, Haifa, Israel

Maury Špíra Lewin, Los Angeles, USA

Jiří Steiner, Prague, Czech Republic

William Wermuth, Konstanz, Germany

Barbara Wesołowska, Będzin, Poland

I give them my thanks for their trust and hospitality.

I was first inspired to investigate the lives of the children of Auschwitz by Tadeusz Szymański (Oświęcim, Poland) in 1972. I am particularly grateful to him for setting up initial contacts and providing advice and documents.

The following offered information and indispensable assistance in putting this book together:

Benton Arnovitz, Washington DC, USA / Jochen August, Berlin, Germany, and Oświęcim, Poland / Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum, Oświęcim, Poland / Leah Bacon, Jerusalem, Israel / Edmund Benter, Gdynia, Poland / Jörn Böhme, Berlin, Germany / Esther Büchler, Lahavot Haviva, Israel / Catriona Corke, Cambridge, UK / Neithard Dahlen, Butzbach, Germany / Neil de Cort, Cambridge, UK / Sabine Dille, Berlin, Germany / Fred Frenkel, Munich, Germany / Daniel Frisch, Göttingen, Germany / Goethe-Insitut, Munich / Ulla Gorges, Berlin, Germany / Elise Heslinga, Cambridge, UK / Christoph Heubner, Berlin, Germany / Margrit Hirsch, Esslingen, Switzerland / Chaim Schlomo Hoffman, Mukachevo, Ukraine / Anne Huhn, Berlin, Germany / International Tracing Service, Bad Arolsen, Germany / Stanisława Iwaszko, Kęty, Poland / Tadeusz Iwaszko, Oświęcim and Kęty, Poland / Tobijas Jafetas, Vilnius, Lithuania / Věra Jilková-Holznerová, Prague, Czech Republic / Miroslav Kárný, Prague, Czech Republic / Adam Klimczyk, Jawiczowice, Poland / Dorota Klimczyk, Kraków, Poland / Emilia Klimczyk, Jawiczowice, Poland / Ewa Klimczyk, Kraków, Poland / Richard Kornfeld, Los Angeles, USA / Ruth Kornfeld, Zurich, Switzerland / Zoltan Kozma, Budapest, Hungary / Helena Kubica, Oświęcim, Poland / Erich Kulka, Jerusalem, Israel / Konrad Kwiet, Sydney, Australia / Richard Levinsohn, Ben Shemen, Israel / Petr Liebl, Prague, Czech Republic / Dietrich Lückoff, Berlin, Germany / Mark Mandelbaum, Naples, FL / Rita McLeod, Saskatoon, Canada / Jan Menkens, Göttingen, Germany / Alan Meyer, Cloppenburg, Germany / Janna Meyer, Paris, France / Moreshet Archives, Givat Haviva, Israel / Leigh Mueller, Cambridge, UK / Musée de l’Holocauste, Montreal, Canada / Simon Pare, Im Dörfli, Switzerland / Jadwiga Pindeska-Lech, Oświęcim, Poland / Wojciech Płosa, Oświęcim, Poland / Karl-Klaus Rabe, Göttingen / Bronisława Rydzikowska, Czaniec, Poland / Aryeh Simon, Tel Aviv, Israel / Maryna Smajovich-Goldenberg, Bilky, Ukraine / Nick Somers, Vienna, Austria / Gerhard Steidl, Göttingen / Ewa Steinerová, Prague, Czech Republic / Irena Szymańska, Oświęcim, Poland / John Thompson, Cambridge, UK / United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington DC, USA / George Weisz, Sydney, Australia / Yad Vashem Memorial, Jerusalem, Israel

Life Before

Heinz Salvator Kounio enjoyed his life as a young boy. He loved his parents, his sister Erika, who was a year older than him, and his grandparents. Of course, there were things he didn’t like so much: the disputes with boys in the neighbourhood or with classmates in the school yard. But in retrospect they were trivial.

Thessaloniki – also known as Saloniki, Salonika (Judeo-Spanish), Selanik (Turkish) or Solun (Bulgarian/Macedonian/Serbian) – the second-largest city in Greece, where he lived, fascinated him and promised a good life for a Jewish boy. Until he was 11.1

At the age of just 24, his father Salvator Kounio had opened a small photo supply shop. That was in 1924. He sold photographic paper and cameras to the many street photographers in Thessaloniki. He obtained his goods from Germany. At the same time, he and his brother exported sheepskins in the opposite direction. He bought them untreated from the farmers in and around Thessaloniki. The skins were then dried and transported by road or sea to Germany. Heinz’s father and brother were very hardworking and were soon well respected far and wide, not only in Thessaloniki but also in Germany. Their customer base grew rapidly.

Every year Heinz’s father visited the photography fair in Leipzig, which was part of the Leipzig industrial fair. There he found out about new products and placed orders for photographic paper, cameras and accessories for the whole year. On one of his business trips, he met the ‘self-assured, obstinate and intelligent’ Helene Löwy (known as Hella). The 18-year-old was a fifth-semester medical student in Leipzig. The two fell in love at first sight. They wanted to get married. Hella was determined to abandon her studies to go with Salvator Kounio to Greece.

The young woman’s parents lived in Karlsbad (Karlovy Vary) in multi-ethnic Czechoslovakia. Her father, Ernst Löwy, was a well-known architect and engineer; her mother Theresa, ‘a beautiful and educated Viennese woman’.

The Jewish inhabitants of Karlsbad have a turbulent history. For around 350 years, they were not allowed to reside permanently there. Only during the spa season from 1 May to 30 September were Jews permitted to stay and do business there. Afterwards, they had to leave again.2

Many Jews had moved since the mid sixteenth century to the surrounding villages, from where they could reach Karlsbad on foot to sell their goods. They were thus able to quickly improve their impoverished situation.

A large number of Jews living and working in Karlsbad during the spa season came from Lichtenstadt (Hroznĕtín). Die Juden und Judengemeinden Böhmens in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart [The Jews and Jewish Communities of Bohemia in the Past and Present] by Hugo Gold, editor-in-chief of the Brno magazine Jüdische Volksstimme, and published in Brno and Prague in 1934, says of this period:

We do not know whether individual Jews lived in those cities before 1568. But after that time a larger Jewish community was gradually established … in the town of Lichtenstadt, just two hours’ walk from Karlsbad. It has an ancient Jewish cemetery and an old synagogue. According to legend it is 1,000 years old, which is naturally a great exaggeration. But it is nevertheless a few centuries old, as the oldest gravestones reveal.3

Over the centuries, the Jews living in the villages near Karlsbad attempted in vain to be allowed to reside permanently in the spa town. Their efforts were not to come to fruition until the mid nineteenth century: a Jewish cemetery was laid out in 1868, and the Great Synagogue was officially dedicated on 4 September 1877.

The Jewish community of Karlsbad grew rapidly: in 1910, there were around 1,600 Jews living there, and by 1931 their number had grown to 2,650, representing 11 per cent of the total population.4

Back to the year 1924 and Salvator Kounio and Hella Löwy’s desire to get married: ‘Neither family’, says Heinz Kounio, ‘was keen on the marriage plans.’ The Löwys asked: ‘Where do you intend to go? Saloniki? To the south? You will be a long way from the vibrant cultural life!’ And the Kounios said of the north: ‘Where does she come from? Karlsbad? The people there have no culture!’

The young couple finally had their way and got married in Karlsbad in 1925. Beforehand, with the help of his parents, Salvator Kounio had had a nice two-storey house built for himself and his young wife right by the sea in Thessaloniki. ‘She should be made to feel at home’ in this part of Europe, which was completely foreign to her.

In fact, Hella Kounio’s new home could look back on an old and vibrant Jewish culture dating back more than twenty centuries. It is thought that the first Jewish families settled in Thessaloniki around 140 bce. The community received a decisive boost from 1492 onwards with the arrival of 15,000 to 20,000 Jews who had been expelled first from Spain, where Jews had lived for more than 2,100 years,5 then a year later from Sicily and Italy, which was ruled by the Spaniards, and then in 1497 from Portugal. At the time, Thessaloniki was part of the Ottoman Empire, which welcomed the Jews with open arms and also guaranteed them freedom of religion.6

The situation remained unchanged for centuries afterwards. The Baseler Nachrichten reported in 1903: ‘The Jews, who manage their affairs independently and in complete freedom, are staunch supporters of the Turkish government. They know that no other power offers the same freedom as they now enjoy under the sign of the crescent.’7

Among the Jewish refugees from 1492 were important and knowledgeable academics, writers, artisans, merchants and Talmudists – students and experts in the Talmud, the primary source of Jewish religious law.

This massive new impetus brought about a radical change in Thessaloniki. The Jewish refugees introduced novel methods of working. Many artisanal businesses were established – silk mills, goldsmiths’ studios, tanneries and, above all, weaving mills, where a large number of new immigrants found work. The conveniently located port became a hub for trade with the Balkans and a centre of European Jewish scholarship.8

Thessaloniki held a great fascination for students from all over the world. The Talmud Torah school founded in 1520 was both a cultural centre supported by the Jewish community and a school of higher education for trainee rabbis.9 It was to produce celebrated doctors, writers and rabbis.10

Over the centuries, other schools and institutes, such as a trade school, boys’ school, girls’ school and apprentice training school were established. The Jewish cultural magazine Ost und West wrote in January 1907: ‘Saloniki has a well-established apprenticeship system. There is none of the frequently insurmountable difficulty found elsewhere in finding a decent master for the young trainees. Most of the master craftsmen in Saloniki are Jews.’11

This development, the spread of modern teaching and training establishments in Thessaloniki, was mainly due to the Alliance israélite universelle, founded by French Jews in Paris in 1860. In Thessaloniki by 1914, around 10,000 students had graduated from the Alliance’s educational institutions.12

Many synagogues existed for centuries in the city. Their names give an indication of the places where the inhabitants had arrived from: Aragon, Kalabrya, Katalan, Kastilia, Lisbon, Majorca, Puglia, Sicilia,13 to cite just a few. During the heyday of Judaism, there were around forty synagogues and prayer houses in Thessaloniki.14

‘Of all the synagogues that of “Arragon” seemed the most picturesque. It is large, and the Alememar [bimah or raised area in the centre of the synagogue where the Torah is read] is a lofty dais at the extreme west end, gallery high. The Ark is also highly placed, and many elders sit on either side on a somewhat lower platform.’15

These lines were written in the late nineteenth century by Elkan Nathan Adler, son of the chief rabbi of England, who called himself a ‘travelling scholar’ and visited Jews in many countries between 1888 and 1914.16

‘“Italia” was more striking’, wrote Adler, who visited Thessaloniki in autumn 1898, ‘for the synagogue is but half-built, the floor not yet bricked in, and the galleries of rough lathes, and yet the women climbed up the giddy steps of the scaffolding, and the hall was full of worshippers.’ In practically all of the synagogues in the city there was a two-hour break between musaf (midday prayer) and mincha (afternoon prayer), when some worshippers took a siesta. Many went to the coffeehouses, full of people, who neither smoked nor drank. During the services, the streets were deserted.17

The journalist Esriel Carlebach, born in Leipzig and later living in Israel, who visited Jewish communities in Europe and beyond, wrote in the early 1930s, about Thessaloniki, that booksellers there offered collections of prayers everywhere for the holidays. But each one recommended a different version. ‘Saloniki had thirty-three synagogues with thirty-three different rites, and a member of a Castilian family would never dare to call to God with Andalusian poems and songs.’18

The Jewish inhabitants formed separate synagogue communities based on their places of origin. They were extensively autonomous and even had their own (limited) jurisdiction. They also administered the districts they lived in, with delegates elected to represent the communities, who met regularly, consulted and adopted decisions on affairs concerning them.19 And the first Jewish printing works was established as early as 1506. Hundreds of publications appeared, and Thessaloniki became ‘the centre of printing in the Near East’.20 The first Jewish newspaper – also the first newspaper in the city – El Lunar, was launched in 1865. It was followed by La Época21 in 1875, and El Avenir22 in 1897. Between 1865 and 1925, seventy-three newspapers were published in Thessaloniki, thirty-five in Judeo-Spanish, twenty-five in Turkish, eight in Greek and five in French.23

Thessaloniki became the ‘Jerusalem of the Balkans’, the ‘Mother of Israel’ or the ‘Mother of Jerusalem’, as the poet Samuel Usque – who was born in Portugal, fled to Italy and later lived in Safed, Palestine – described the city during a visit in the mid sixteenth century:24

Saloniki is a devout city. The Jews from Europe and other areas where they are persecuted and expelled find shelter in the shade of this city and are as warmly welcomed by it as if it were our venerable mother Jerusalem itself. The surrounding countryside is irrigated by many rivers. Its vegetation is lush and nowhere are their more beautiful trees. Their fruit is excellent.25

According to official Turkish sources, in 1519 over 50 per cent of the population of Thessaloniki were Jews: 15,715 children, women and men, compared with 6,870 Muslims and 6,635 Christians. The situation had barely changed by the end of the nineteenth century, when there were over 70,000 Jews in the city – again, half of the population.26

Thessaloniki’s privileged position in international trade gradually declined as a result of the transformation of the world economy. The burgeoning transatlantic economy, particularly the rise of the Netherlands and England, shifted the traditional balance.27 It was not until the second half of the nineteenth century that the revival of trade relations with the Mediterranean ports of western Europe helped the city to flourish again.28

At this time, Jews were present in all professions. There were 40 Jewish chemists, 30 lawyers, 45 doctors and dentists, 150 fishermen, 500 waggoneers and carters, 220 self-employed artisans, 100 domestics, 3 engineers, 10 journalists, 2,000 waiters, 8,000 retailers and wholesalers, 60 colliers, 2,000 porters, 300 teachers, 250 butchers, 600 boatmen and 50 carpenters. There were also several Jewish businesses: a brewery, nine flour mills, twelve soap factories, thirty weaving mills and a brickworks.29

At the end of October 1912, during the First Balkan War waged by Bulgaria, Greece, Montenegro and Serbia against the Ottoman Empire, Thessaloniki became part of Greece,30 bringing many Greeks to the city as a result.31

In August 1917, the city was extensively destroyed in a huge conflagration. The Jewish districts were particularly hard hit. Around 50,000 Jews became homeless. The Greek government promised to compensate them for their losses, but the Jews were not allowed to return to certain parts of the city. This prompted many Jews to leave Thessaloniki. They emigrated to Alexandria (Egypt), Great Britain, France, Italy and the USA.32

After the Greco-Turkish War (1919–22), an exchange of populations was agreed. A large number of Greeks living in Anatolia in Turkey were forced to move to Thessaloniki. In return, the Muslim inhabitants had to leave the city.33 As a result of all these events, within a few years the Jewish population became a minority.34 According to the first Greek population census of 1913, 61,439 of the 157,889 inhabitants were Jews.35 By the early 1930s, Jewish children, women and men made up only around 20 per cent of the population.36 One contributing factor was a law promulgated in the early 1920s prohibiting the inhabitants of Thessaloniki from working on Sundays, prompting a further Jewish emigration.37 For several centuries previously, the Jews had not worked on Saturdays: during Shabbat, no ships were unloaded and no stores were open.38 This was still the case in 1898: ‘All the boatmen of the port are Jews, and on Saturdays no steamer can load or discharge cargo.’39

For over 400 years, the language brought from Spain remained the lingua franca of the persecuted Jews who had fled to Thessaloniki. Anyone visiting the city between 1500 and the early twentieth century who sat down, closed their eyes and listened to the people talking could imagine they were in a Spanish city. For many generations, the city was mostly Spanish-speaking and Jewish. The Greek Christians, Slavs and Muslims in Thessaloniki also spoke Spanish and conducted their daily business in it.40

‘There are people and lifestyles that are rightly called Sephardic, which means Spanish’,41 wrote the journalist Esriel Carlebach around 1930. He continued: ‘When two Sephardim met, they spoke Spanish; when two families married, the ceremony was performed according to the rites of Seville and Cordoba; when they built a house there was a patio in the centre surrounded by a small number of cool rooms with mosaic floors, grated windows and Moorish paintings.’42

The Jewish version of Spanish spoken in Thessaloniki was sprinkled with terms and phrases from Hebrew, but also from Portuguese, and, in the last decades of the nineteenth and early decades of the twentieth centuries, also from Turkish, Italian and – particularly during this time – French. These influences blended over the centuries in Thessaloniki to produce an autonomous language of particular beauty, known as Judeo-Spanish, Spaniolish or Ladino, although the latter refers not to the vernacular Judeo-Spanish but to the liturgical language: ‘Ladino is used to introduce worshippers to the Hebrew original in a manner that is not genuine Spanish but rather a … hispanicized Hebrew.’43 ‘Indeed, the amount of Ladino introduced into the service was quite astonishing’, wrote the travelling scholar Elkan Nathan Adler in the late nineteenth century. ‘Most of the Techinnoth, Confessions and Selichoth were in the vernacular, and the Reader seemed really moved as he held forth in that language.’44

From the second half of the nineteenth century, French became increasingly the language of ‘culture and elites … on account of the economic western orientation’, but the vast majority of Jewish inhabitants continued principally or exclusively to use Judeo-Spanish as their everyday language.45

Myriam Kounio, Heinz and Erica’s grandmother, also spoke almost exclusively ‘Spaniolish’, as the language was called in the family. For that reason, the children, although they could also speak it a little, were not able to communicate very well with her. At home, the younger family members and their grandfather, Moshe Kounio, spoke Greek. With their mother, Heinz and Erica spoke her native language, German. Thus, the children grew up with ‘two and a half languages’.46 ‘We were not a strictly religious family’, says Heinz Kounio. They went to the synagogue ‘of course’ on Shabbat and all major holidays. And on those days, he and his sister didn’t go to school. ‘But we were an open-minded family interested in culture. Books, theatre and concert visits were part of our lives.’

Heinz and his sister attended the Greek school from Year 1. ‘But we also had classes in Jewish schools. And religious instruction took place in the Jewish community. In the holidays we went to Karlsbad. It was fantastic there. Where my grandparents lived there was a lake of around 1 hectare in size. We often took a boat out. We went on walks a lot, and the forests there were marvellous.’ They strolled through Karlsbad, a well-known spa, with their grandparents, who looked forward impatiently to the children’s visit every summer. They drank the water – at a temperature of 42 to 73 degrees – from the healing springs, and the highpoint of their excursions was a visit to the expensive cake shop at Hotel Pupp. ‘It was a completely different world from Saloniki. But just as nice. The weeks flew by. I have a very fond memory of those times.’

In Thessaloniki, they also spent every free minute outdoors. ‘We played a lot. Our friends were the neighbourhood children – also non-Jewish children, although several Jewish families lived in our street. Most of my friends were Christian. But there were also four Jewish boys I got on well with.’

Their house was right next to the sea. ‘It was a fantastic district. As soon as the weather allowed, my sister and I spent the entire day on the beach or in the water.’ They had a small white rowing boat, which they used extensively.

Even as a small boy, Heinz had a great passion – namely, fishing. He would get up early and prepare the bait, a well-kneaded mixture of bread and cheese, and then sit with his fishing rod for hours, above all catching mullet, of which there are around eighty varieties worldwide. And with his sister Erika he caught crabs, which their mother cooked. ‘A delicious special treat.’

Heinz still recalls the ‘chamalis’ or porters:47 ‘They were almost all Jews.’ They carried the goods unloaded in the port of Thessaloniki to the city and the nearby mountain villages in horse-drawn carts, or pulled them in elongated handcarts on the narrow mountain roads.

The chamalis were very strong and could carry over 100 kg on their backs up to the third or fourth floor of the houses. And when they came down from the mountains and ran down the streets at great speed with the handcarts, they made a lot of noise and shouted: ‘Watch out! Get out the way!’ The carts had a bell that rang constantly. And when they came to a crossroads, everyone stopped. They always had priority. The chamalis were very well known and a typical feature of Saloniki at the time.

The hardworking Jewish dockers in the port of the picturesque city on the Thermaic Gulf were also famous. The Viennese newspaper Die Stimme – Jüdische Zeitung reported on 20 November 1934: ‘Aba Houchi, member of the board of the Histadrut ha-Ovdim [labour federation] of Haifa, arrived in Saloniki to choose 100 to 150 Jewish dockers for immediate resettlement in Palestine. These dockers will work mostly in the port of Haifa but also in Jaffa. There are already 300 Jewish dockers’ families from Saloniki living in Palestine.’48

Heinz Kounio: ‘If you get into a taxi in Haifa today and ask to hear a Greek song, the driver will put one on for you. Many of these taxi drivers are descendants of those first dockers from Thessaloniki.’

In spite of the recurrent expulsion, persecution and pogroms,49 there was Jewish life everywhere in Europe. The creativity and work of Jewish researchers, industrialists, painters, doctors, musicians, politicians and writers had a far-reaching impact in many countries. In large parts of Europe, they were and are part of the history not only of the Jewish people but also, for example, of the people of Austria, Belarus, Belgium, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Slovakia, Switzerland and Ukraine.

Before the Nazi era, there were few cities in Europe, large or small, which did not have Jewish children, women and men living in them, often for several hundred years, in some cities and regions for over 1,000 or 2,000 years. Well over 30,000 localities in Europe had Jewish inhabitants.50

Dáša Friedová spent the first years of her life with her parents, Otto and Kát’a Fried, and her sister Sylva, three years older than her, in the small Czech village of Odolice. It was around 40 kilometres north-east of the German border. The parents owned a large farm with 360 hectares of land. The village had around 150 inhabitants, Czechs and Germans. The Frieds were the only Jews.

When the neighbours slaughtered a pig, they gave some to the Frieds. ‘We did the same. We gave them grain or whatever our neighbours and friends needed. This was the way we were, and the Germans living in the village were not excluded.’ The Frieds did not keep kosher. ‘We cooked and ate just about everything.’ They regarded themselves as Czech but still celebrated Pesach, recalling the exodus from Egypt, and Purim, commemorating the rescue of the Persian Jews. These were large family gatherings. But they also celebrated Easter and Christmas with their Christian friends and employees.

Dáša and Sylva’s closest friends were the daughters of her father’s employees who worked on the farm. ‘We played together every day and were good friends.’ Dáša and Sylva went to the village school like the other children. The school consisted of two rooms, one for the smaller children up to Year 3, and the other for the older girls and boys. ‘We were the only Jewish children in the school and village, but it was not an issue. We never felt any antisemitism, not even from the German children.’

The Fried family travelled regularly to Most, a short drive from Odolice. The town was a trading hub and centre of the large brown-coal field in north-western Bohemia. In 1930, Most had a population of around 28,000, including 662 Jews. The history of the Jewish community dated back to the fourteenth century, and since 1872–3 it had had its own synagogue, which was destroyed by the Nazis in 1938.51 The old Jewish cemetery survives to this day as the last relic of the Jewish citizens of Most.

In the 1930s, the Frieds travelled to Most to do their shopping, visit the theatre or spend their Sundays in the park of the nearby spa resort Bílina. Jews had been documented in Bílina since the fifteenth century. The Jewish cemetery was laid out in 1891 and a synagogue was dedicated four years later. In the early 1930s, the rabbi of Bílina, A. H. Teller, noted: ‘[The Jewish community] has 120 souls and around 50 taxpayers. The community has a temple and cemetery in good condition. May the community be allowed to continue in future to work for the benefit of Judaism through the peaceful collaboration with all members.’52

The main attraction for the Fried family was the public mineral spring in the park. ‘My father played cards and my mother chatted with other women. Sylva and I played with our governesses or with other children whom we met by chance in the park.’

On the major holidays, the family went to the Moorish-style Jubilee Synagogue,53 built in 1905–6, Prague’s largest Jewish prayer house on Jeruzalémská, among other things to meet up with their relatives. The parents also took their children to the Jewish cemetery in Prague, where they placed small stones on the gravestones in memory of the deceased. ‘Visitors to a cemetery always left a stone. It’s a Jewish tradition all over the world.’ The family travelled once a week to the capital, 80 kilometres away. ‘We had lots of relatives in Prague – aunts, uncles and cousins. We were all very close and enjoyed each other’s company. It was always a great family occasion.’

‘I have only good memories of the first nine years of my childhood. It was a nice, happy time.’

Gábor Hirsch The ‘King of Trains’ – more precisely, one of the routes of the Orient Express – passed from the 1920s through the town of Békéscsaba in south-eastern Hungary.54 Even as a boy, Gábor Hirsch was fascinated by it, imagining the adventure, glamour and unknown worlds associated with this special train.

Gábor’s father János owned an electrical supply and radio shop in Békéscsaba, which he had opened around 1925 with his uncle Ferenc. The uncle emigrated a few years later to Egypt, after which János ran the business on his own. His wife Ella was one of the sales assistants. In its heyday, the business had between ten and fifteen trainees.55

Békéscsaba had a population of around 50,000 at the time, of whom some 2,500, or perhaps 3,000, were Jews, like the Hirsch family.56 The Jewish community of Békéscsaba dates back to the end of the eighteenth century. The oldest gravestone in the Jewish cemetery of the Neolog (reform) community is of Jakob Singer, who died in 1821. A monument in the town park commemorates the victims of a cholera epidemic of 1825, including eleven Jews. According to Gábor Hirsch’s research, there were two independent religious Jewish communities in Békéscsaba after 1883: the orthodox, and the liberal – or Neolog – community, which the Hirsch family belonged to. The first synagogue was built in 1850, and a second one for the orthodox community was built in 1894.57 The two synagogues faced one another on either side of Luther Street.

Gábor’s Austrian nanny was called Hildegard. She was around 25 years old and he got on well with her. His mother wanted him to learn languages. ‘She believed it was important. That’s why we had Hildegard.’ From 1933, Gábor attended a private German-language kindergarten, and in 1936 he started at the Neolog community’s Jewish elementary school. ‘There were only three boys and thirteen girls in my class, two of whom were not Jewish.’

The Hirsch family were so-called ‘three-day Jews’. They celebrated the High Holidays: Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish new year, at the end of the summer, marking the start of autumn; then, ten days later, Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement at the end of forty days of repentance.

In 1940, Gábor switched to the Evangelical Rudolf-Gymnasium. There were fifty-four boys and girls in his class, including four Jewish pupils, ‘more than usual for the time’. While the non-Jewish children had religious instruction, they were allowed to play in the school yard. ‘We had religion classes at other times in the Jewish community rooms.’ One of his teachers was the rabbi Jakob Silberfeld, who was murdered in Auschwitz in the summer of 1944.58

And, ‘naturally’, Shabbat, the weekly day of rest from Friday to Saturday evening, was particularly important for the Hirsch family. ‘On Friday evening, we lit the candles and ate the Shabbat bread, the braided poppyseed loaf.’