Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

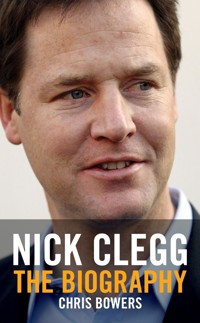

In early April 2010 Nick Clegg was fighting for recognition, even as the young, fresh and personable leader of Britain's third political party. Two weeks later he was the focus of 'Cleggmania' and his popularity was compared with Churchill's. Four weeks after that he became the second most important figure in the government - but within a year he was ridiculed and reviled as popular hopes turned to disappointment. But who is Nick Clegg? What has made him the man he is today? By what route did he enjoy one of the most spectacular rises - and falls - in British politics? This fully revised and updated edition of Chris Bowers' acclaimed biography contains an analysis of the first years of coalition government, and tells us what we can expect of the Deputy Prime Minister as the next general election approaches. With a lightness of touch that captures the spirit of the unstuffy Lib Dem leader, and with the benefit of access to Clegg himself and the many people who have shaped and worked with him, Bowers presents a sensitive, critical and above all insightful portrait of one of the leading political figures of our age.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 668

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

By Chris Bowers

NICK CLEGG: THE BIOGRAPHY

CONTENTS

Title Page

Author’s Introduction: ‘A special one?’

1. ‘A little of all these’

2. ‘All are guilty of some atrocity’

3. ‘Nickje’

4. ‘Something visceral about him’

5. ‘You scoundrels and cowards’

6. ‘The brightest young man I’ve ever come across’

7. ‘Unbundling the local loop’

8. ‘Returning with the mark of Satan on him’

9. ‘We have to do something about this’

10. ‘One plus one equals more than two’

11. ‘Might be shot in four or five years’

12. ‘The lightning rod’

13. ‘This is a bitter blow’

14. ‘What is the most liberal thing to do?’

Bibliography

Index

Copyright

Author’s Introduction

‘A SPECIAL ONE?’

IN SHOW business it’s sometimes said that you can spend twenty years becoming an overnight star. The turn of phrase refers to someone who plays the pubs and clubs week in, week out for years; then suddenly one night a television executive happens to be in the audience, spots the talent, and within a few months the performer is a household name.

In many ways, Nick Clegg spent twenty years becoming an overnight star, but his instant stardom was somewhat different. On 15 April 2010, close to ten million people crowded round their televisions to follow the first-ever party leaders’ debate in British politics. It was a phenomenal audience for a political programme, especially among a population that had taken great pride in moaning about its politicians – and with a fair bit of good reason in view of certain ridiculously audacious expenses claims that some MPs had submitted in the previous eighteen months. But with no obvious result being predicted by the opinion polls, and finally a chance to see the leaders debate with each other after years of witnessing it in America and other countries, the British people revelled in their televised political spectacle.

To some, Nick Clegg shouldn’t have been part of it. As the leader of the third party in British politics, there was an argument that he represented a party that could never aspire to government, certainly not on its own, and that he was therefore cashing in on being the leader of the biggest of the non-major parties. That argument was a bit harsh – there was a big gap between the Liberal Democrats and any other party in UK terms, and the legal requirement for the broadcasters to observe ‘due impartiality’ meant they would have had a tough time if they had stuck to Labour and Conservatives alone. So this was Clegg’s party’s big opportunity in modern British politics, and he knew it.

I followed the debate from my living room, watching it with my wife, who is no political animal despite being married to me – she was one of the normally apolitical folk who swelled the audience to that astonishing figure. I didn’t actually think Clegg did that well. He is a good media performer without being an outstanding one, and I felt he came over as well meaning but having difficulty hiding the fact that he was very wet behind the ears. So when I heard the newsreader on the ITN News at Ten say that a first opinion poll had been taken and ‘there is a clear winner’, I assumed it had to be David Cameron. Cameron hadn’t done that well, but he’d looked like a plausible prime minister, while Gordon Brown’s ‘I agree with Nick’ approach had clearly backfired.

I was therefore as much gobsmacked as delighted when the polls showed that Clegg had emerged as the clear winner from the debate. Was he that good? Had I missed something, locked as I was in my own Lib Dem parliamentary campaign to wrest a Tory stronghold away from the Conservatives?

Clegg did many things right that night. His trick of mentioning the questioner by name but addressing the television audience by looking straight into the camera clearly worked, and contrasted with a nervous Cameron and an uncomfortable Brown. But the biggest trump card Clegg had was that not a lot of people knew him. That was hard for those of us in the party to take, because we’d been aware of him since 1999, when he became one of the few MEPs any of us could name. To us, the idea peddled in the media that Clegg was ‘Cameron-lite’, because he looked too like David Cameron for his own good, was preposterous. How could anyone in their right mind mix those two up?

Well, they could, because a lot of people in Britain don’t take that much interest in politics, and if they do, they generally think of it in terms of Labour and Conservative; or certainly did until the current coalition was formed. Much as we Lib Dems didn’t like to admit it, we were in many cases the nicest of the protest votes, a generally cuddly way of expressing dissatisfaction with the two largest parties. As a result, quite a few people could name the leader of the Lib Dems, but not that many, and of those, not everyone would have been able to tell you what he looked like, especially as it was his first general election as leader of the party.

So after twenty years as a political animal and more than ten as an elected representative, Nick Clegg became an overnight star. In retrospect it is remarkable to think that, on the morning of 15 April 2010, he was just a name even to those who had taken an interest in the forthcoming election; and by 12 May he was the Deputy Prime Minister and one of five Liberal Cabinet ministers in the government for the first time in sixty-five years. Even in the best political fiction, people just don’t rise that fast. Nor do they sink as fast as he appeared to in the months after the Conservative–Lib Dem coalition was formed, although I suspect he has not sunk as far as many in the media would have us believe.

I did some work with Clegg in the months before he became Lib Dem leader. I had met him in February 2007, when he was the guest speaker at our constituency’s annual dinner, at which I was master of ceremonies. He impressed us greatly that night. In his speech, he described our local MP, Norman Baker, as ‘a cross between Gandhi and a battering ram’, an original formulation that will strike a chord with anyone who knows the sensitive but ebullient Baker, and the comment certainly wowed party members. Sitting next to him over dinner, I found Clegg a great conversation partner, but what struck me most was his total ease with everyone he met. Like any local party, we have a mix of personalities, from the hard-working salt-of-the-earth characters you can’t do without, to those who take a fair bit of space and need a lot of maintenance. It’s the politician’s job to treat them all with respect and ease, but he had something special. It was almost entrancing watching him interact with someone new, male or female, seeing him look into their eyes, tilt his head slightly, and watching them go weak at the knees. Some call it charm, others call it charisma. Whatever you call it, he had it.

The line of argument I put to him in February 2007 was that Ming Campbell wouldn’t last that long as Lib Dem leader, and that when he went, he, Clegg, had to take over. He was quite happy with that scenario; indeed, he had heard it enough from others. But the second half of my argument was that the next leader of the Lib Dems had to really understand the environment. The political noses of Campbell and Charles Kennedy had told them that the environment was important, but I never got the impression it was something they really felt. Faced with the onward march of the Green Party (something all Lib Dems welcome, but few dare say so because the Greens are a threat to them politically), I said that if the next Lib Dem leader didn’t have a fair bit of green blood coursing through his/her veins, the party would remain vulnerable to the Greens.

Out of that began a series of meetings, at which Clegg, I and a handful of other people thrashed out an environmental policy for his forthcoming leadership campaign. This was in the middle of 2007, and none of us realised just how close the leadership campaign was. There were about five meetings; one was on the terrace at the House of Commons, another in a room in the Grand Hotel in Brighton during the party conference, which stands out in my memory for the awful sandwich (bitingly and hilariously described by Clegg) he tried to munch his way through while we chatted. Our last meeting took place – purely coincidentally – on the day Campbell resigned as leader, and while I barely saw Clegg in the three years after that, many of his early environmental pronouncements bore the hallmarks of our discussions. Whether I really got him to feel the environment is another matter, and this point is developed in Chapter 10, which deals with how the party worked out its first manifesto under his leadership.

When news was published that I was writing this book, a few people were quick to dismiss my Lib Dem background as detracting from the biography’s credibility. It would be too much of a PR job to be truly independent, or so the argument ran. That overlooks the fact that I am a journalist first and a Lib Dem in my spare time, and that I have too much professional pride to offer up a sanitised profile of a man with a vital role in British life. In fact my professional pride was something that worried some senior Lib Dem figures, who feared I might look to be hypercritical of Clegg just to assert my journalistic independence. I hope I have been neither unnecessarily harsh nor unnecessarily lenient.

But I also think that to assume I would somehow gloss over Clegg’s bad points because I’m a member of his party rather misses a stark reality of politics in a country of sixty million inhabitants.

For any political party to be viable, it has to be big enough to draw people from a wide spectrum of opinion. To that extent, all three major British parties are broad churches, and I find it journalistically fatuous when I read headlines about ‘splits’ in parties. If there aren’t splits in parties occasionally, then the party is too small or too dormant. One person’s split is another person’s healthy debate, and I much prefer the healthy debate interpretation, whether in my own party or others. So the fact that I’m a Lib Dem councillor and former parliamentary candidate does not mean I feel the need to present a sanitised portrait of my party leader, just a fair one.

Moreover, there is no shortage of Lib Dems who are happy to tell you – in a quiet way that doesn’t lead to headlines about ‘splits’ – that they’re not totally enamoured of Clegg’s leadership. By taking the party into a coalition with the Conservatives, he has fuelled the fires of those who always saw him as being ‘on the right of the party’, whatever that means. More than a year into that coalition, many feel he has not shouted loudly enough about policy successes that happened only because the Lib Dems were in government. And he won a leadership contest by the narrowest of margins against Chris Huhne, a man who, though rich enough to rub shoulders with the best of the bankers, had worked his way to the party’s heart with a superb environment policy that set out a timetable for Britain to become carbon neutral by 2050.

For these and other reasons, I had no difficulty coming at this book with an open mind, expecting to find good things and not-so-good things, all of which would contribute to an overall profile of a man who still has a lot of his career to come. I have indeed found the full package, but one overriding impression has emerged over the course of several months’ research: I have grown both to like and to admire the man. That realisation in itself didn’t altogether surprise me. What I was slightly unprepared for was the amount of people who used the word ‘special’ in connection with him. The current zeitgeist in Britain is to use the word ‘special’ to describe a person as a bit dangerous; the media has had a lot of fun with the Portuguese football coach José Mourinho since he once said he was ‘the special one’. But several people – and I mean several – who have no specific knowledge of Mourinho have said to me ‘You do know you’re writing a book about a very special person, don’t you?’ It doesn’t mean one has to agree with everything Clegg says or does, but the suggestion is that here is a package of skills and attributes that is unusual, a package that, if used wisely, could have the scope to effect significant change in British society, even after the setbacks he and his party suffered in the May 2011 elections.

Yet this combination of my own findings and the observations of others presents me with my biggest problem: can I really paint a portrait of a man that is generally positive without people dismissing it as the biased analysis of a party member? At time of writing, the problem is particularly acute, given that the political media are delighting in what they see as Clegg’s spectacular fall from the height of ‘Cleggmania’ a little over a year ago. However, as a journalist, I am well aware that the media can get very caught up in today’s headlines and lose sight of the big picture, as the former sells a lot more papers than the latter. And as a sports journalist, I will just have to rely on the commentator’s maxim of ‘calling it as I see it’, and trust the reader to see it as the honest profile I intend it to be. (And to remember that, while I have stood for the Lib Dems, the publisher of this book has stood for the Conservatives.)

Whatever one thinks of Nick Clegg, he has achieved remarkable things for himself and the Liberal Democrats. He became leader less than three years after becoming an MP. Two-and-a-half years later he was the Deputy Prime Minister, with four other Lib Dem ministers in the Cabinet and a dozen or so junior ministers further down the ministerial ranks. That is a phenomenal achievement, even if many in his party are still uncomfortable at what they see as supping with the Conservative devil.

But who is Nick Clegg? Where has he come from? What drives him? Or to use a phrase beloved of Lib Dems, what makes him get out of bed in the morning? What lies behind the boyish charm that can sometimes turn to a look of teenage grumpiness? And what makes him sacrifice the easy life that someone of his circumstances could have had, in return for life in the public eye where every syllable is scrutinised for hidden meanings, leading a party with no safe parliamentary seats, dealing with unseen abuse to himself and his family, and having to work hardest of all to ensure he doesn’t miss his kids growing up? All that makes up the content of this book.

People ask me whether it’s ‘authorised’ or not. I don’t like that phrase, as it gives the impression of being somehow controlled or ordered by Clegg or his staff. It is my book, and I take responsibility for it. But I am very grateful to have had the cooperation of both Nick himself and just about everyone in the Lib Dems. I’m especially grateful to Norman Lamb, Lena Pietsch and Jonny Oates, who have been supportive of my project, even though it was clearly an irritant for them when it emerged amid the bedlam of the post-election period. The one restriction they and Nick put on me was in interviewing the Clegg family – they said that was a ‘no go’ area. I fully accepted this in terms of Miriam (Clegg’s wife) and their three sons, Antonio, Alberto and Miguel – anyone would want their children to be protected from the kind of public intrusion Nick and Miriam are trying to shield them from. As such, the details of their private life that appear in this book are only those already in the public domain, or information close associates have been happy to tell me. But I did seek access to the family Clegg grew up in, as family background is an important part of depicting the man. I’m grateful to Clegg and his staff for the compromises they were willing to make so that I could gain an insight into the world in which he grew up.

In addition, Clegg himself gave me quality time, for which I am very grateful, and I was also able to spend time with him on the campaign trail in April 2011. But in this book I quote him from other sources than just the interviews I carried out with him. This is not simply a question of avoiding reinventing the wheel, but also to quote him as he expresses himself to others. As a result, I quote frequently from his appearance on BBC Radio 4’s Desert Island Discs in October 2010, from an in-depth interview he gave Mick Brown for an article in The Telegraph magazine in March 2010, and an interview with the Ekklesia website in 2008, as well as from other articles, accounts and interviews.

And I am eternally grateful to all the people who have given me the benefit of their knowledge of Nick, and other bits of logistical help. I carried out more than fifty interviews for this book. Most of those who helped me are quoted in the text, but inevitably there were some whose help was of a more logistical than quotable nature. They include, in alphabetical order: Matthew Bishop, John Bowers, John Bridges, Joaquín Carvanna, Monica Escolar-Rojo, Richard Evans, Sebastián Fest, Anne Gorst, Sandy Harwitt, Greg Hodder, Gayle Hunnicutt, Harvey Linehan, David Mercer, Mariëtte Pakker, Chris Rennard, Alison Suttie and Steve Wasserman. And I’m also very grateful to Iain Dale of Biteback Publishing, who offered me the authorship of this book rather than taking the possibly safer option of giving it to a Westminster journalist. I agree with Iain on political matters no more these days than I did when we were students of German together in Norwich in the early 1980s, but I’m delighted to be a small part of his immense contribution to the popular understanding of British politics.

Ultimately, this book is not about being critical or uncritical of Nick Clegg, but about painting a picture of him. As such, it should be possible for those who are well disposed towards him to enjoy this book and get something out of it, as much as for those who are not. He is, after all, one of the dominant political figures of our era, so the public is entitled to know what makes him tick, whatever they may think about the man, his background, and his views.

Chris Bowers, July 2011

Chapter 1

‘A LITTLE OF ALL THESE’

WATCHING NICK Clegg up close can be a daunting experience for British people. For a country not used to proficiency in foreign languages, the ease with which he switches tongues is disconcerting. ‘I was staying at his house once,’ recalls a close aide, ‘and he was on the phone to his mother, with his wife hanging on to speak to him. He was rattling on in Dutch, and then when the call ended, he muttered a couple of words in English to me, picked up the other phone, and started rattling away in Spanish with Miriam.’

Such linguistic dexterity is nothing special in multilingual countries. In Switzerland, for example, a country with four official languages alongside the onward march of English, trilingualism is fairly common. But in Britain, even after two generations of immigration that have left many children and young adults bilingual, the ability to speak a foreign language is still held in awe. Choosing a different form of language – what the language analysts would call different ‘registers’ – for different people and different situations is nothing special; people use different words or modify a regional accent when speaking to children, the vicar, a solicitor and so on. So too does Nick Clegg – only in his case it’s a totally different language rather than a different register.

A linguistic genius, then? Linguistically gifted, for sure, and his aptitude was always more towards the humanities subjects than the sciences, but his multilingualism stems as much from his background and upbringing as from any natural genius.

Of Clegg’s four grandparents, only one was British. Two were Dutch, and one was Russian. How much anyone is influenced by their ancestry and family heritage is open to question, and it’s a question that has dogged the offspring of despotic parents and grandparents as much as those from admirable stock. But there’s no doubt there’s a mass of drama, intrigue and entertainment in Nick Clegg’s family heritage, most of it through his two grandmothers. His brother Paul, six-and-a-half years older than Nick and therefore with a more formed memory of that generation, says of their four grandparents, ‘As a child, you pick out people who are defined – people who aren’t defined blur into the background. All my grandparents were very defined characters, they were all interesting.’

The most colourful, even romantic, line of the Clegg family is the Russian one. His paternal grandmother was Baroness Kira von Engelhardt, the daughter of Baron Artur von Engelhardt and Alexandra Ignatievna Zakrevskaya. Baron Engelhardt was a landowner of noble German origin from Smolensk, whilst Alexandra was a Russian noble of Ukrainian descent, whose father was Ignaty Zakrevsky, a senator and one-time attorney general answering to the tsar of Russia. Kira was born in 1909, so was just eight when the Russian Revolution wiped out her family’s property. The Engelhardts fled the Bolsheviks and settled in Estonia, where Kira lived with her cousins on her uncle’s estate. In the 1920s she came to London and, among other things, became a lifelong supporter of the Liberal Party.

‘She was a lovely woman,’ recalls Paul Clegg of Kira. ‘She was really gentle, and she was somebody who bore no grudges yet lived during a time in history when people could have borne an enormous amount of grudges. Her endearing quality to me was that she was endlessly interested and had no backward-looking regrets at all. She was quadrilingual [French, German, Russian and English] and we were all very fond of her.’

The most colourful member of the family was Alexandra’s sister – Nick Clegg’s great-great-aunt – Maria Ignatievna Zakrevskaya. For most of her life, she was known as Moura Budberg, and looked after Clegg’s grandmother (her niece) as a sort of mother substitute when they were all exiled in London. She died in 1974, when Nick was seven. He does recall meeting her on a handful of occasions: ‘She was a pretty imposing figure, utterly terrifying for a small boy,’ he has said in interviews. ‘She would visit us and look at me sternly and say in a thick Russian accent, “Speak up, boy, you mumble, you mumble.” But she was an extraordinary survivor who rebuilt her life in London and became a great figure on the Bohemian, theatre and arts scene in London. She would hold soirées and salons, people would come, and she would drink everybody under the table.’

Paul Clegg, who was thirteen when Budberg died, has a somewhat more robust memory of her. ‘She was quite a character, a strong older woman who people respected, and everyone in our immediate family who really knew her, mainly my parents’ generation, talks about her as a key central figure, as any matriarch would be. I remember her as a really good person, and very much loved by all her family.’

Budberg was born in St Petersburg in 1892, the daughter of a wealthy imperial official. An obituary of her daughter Tania published in The Times in 2004 describes Budberg as ‘a spoilt but exceptionally attractive and spirited girl of 18’ when she married her first husband, Count Johann von Benckendorff, a tsarist diplomat. They had two children but, in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution, he was shot dead by a peasant on their estate in Estonia, which at the time was in the process of gaining independence from Russia. Kira was with her nanny, Mrs Wilson, when they found him dead on a path near the house. Many years later she and her husband Hugh Clegg went back, visited the house and located the spot where the count had died.

Nick Clegg also visited both St Petersburg and Estonia. When he was working at the European Commission on Russian and central Asian development issues in the mid-1990s, his itinerary took him to St Petersburg, and he snuck in a taxi ride past the house the Engelhardts had had there. ‘I only saw the house out of the window of the taxi, but I was bowled over by the romance of St Petersburg,’ he says. ‘I remember being gobsmacked by the absolute beauty of the place – it was the middle of winter, you had great shards of ice coming up the river, the statue of the horseman, it was beautiful. I met a young man, he could well have been an interpreter, who took me to a library, and he became wildly excited to show me books about the Budberg family and Zakrevsky – he knew all about them.’

A more moving experience came on a separate trip, when he visited the house in Kalli Järv, Estonia, where Kira and Moura spent some time and where the Count was shot dead. ‘There’s a path from the big house, which is now an agricultural college, to the smaller wooden house on the banks of the lake where they lived, and there is a small wooden engraved statue where he was shot. I was in a suit, with snow up to my knees! I don’t know why it hit me emotionally – it was the middle of winter and the middle of nowhere, it was where he was shot, and I’d heard all these stories about a house on a lake, and it was exactly as I’d imagined it.’

Caught up in the post-revolution chaos, Moura Budberg had an affair with Robert Bruce Lockhart, a British diplomat posted to Russia during the Russian Revolution and in reality a leading British spy. Lockhart, who legend says was the man on whom Ian Fleming based the character of James Bond, was suspected of being involved in a plot to assassinate Lenin in August 1918, may in fact have been the man behind it. Lenin was shot three times but survived the attack. Legend also has it that Budberg and Lockhart were lying in bed in his Moscow flat shortly after the attack when revolutionary soldiers burst in and arrested them both. They were imprisoned, but she was soon released and he got out a little later; much speculation surrounds what favours Budberg offered the prison commandant as part of both her own and Lockhart’s release. Budberg was deeply in love with Lockhart, and felt utterly deserted when he eventually left her.

Budberg took a lot of secrets about this time to her grave, so no-one can be quite sure what really happened. As a result, and because she was a sexually liberated woman, her past gives rise to many tales and intermittent lurid headlines about Nick Clegg’s ‘Mata Hari aunt’. But the family is keen to make sure the good side of Budberg is also known, as she proved to be a haven of support for her friends and family over many years.

After the liaison with Lockhart, Budberg fell in love with the Russian revolutionary writer and literary giant Maxim Gorky, which helped her survive the early years of the new Soviet state. He introduced her to Lenin and Stalin, and she apparently gave Stalin the gift of an accordion. Around this time she married another member of the Baltic aristocracy, Baron Nikolai Budberg Böningshausen, but it was a marriage of convenience for her to get Estonian citizenship. Once she had it, she ditched him, but kept the title and was known for the rest of her life as Baroness Moura Budberg.

Budberg’s relationship with Gorky lasted for several years, during which time he introduced her to the British science fiction writer H. G. Wells. In the early 1930s, Budberg settled in London, and began an affair with Wells, despite being thirty years his junior; she is said to have told Somerset Maugham that Wells ‘smells of honey’. Her home was in Ennismore Gardens, close to one of London’s two Russian Orthodox churches (although as the church in Ennismore Gardens recognised the authority of the patriarch in Moscow, it was treated with suspicion by Russian émigrés, especially during the Cold War years). Her move to Britain began a period of four decades at the core of London’s international social set, in which she displayed a phenomenal ability to drink large amounts of vodka without losing her quickness of thought. Yet she could never shake off suspicions that she was a spy; in fact she may not have wanted to, such suspicions giving her a cachet in London circles that no doubt enhanced her allure. She was probably a double agent, and may even have spied on or for Germany in the First World War: the British authorities considered her ‘a very dangerous woman’ in the aftermath of the revolution, but they almost certainly used her knowledge of Russia during her time in London.

How much credence they gave her evidence is another matter, highlighted by an incident in 1951 that came to light when MI5 released her file in 2002. Not long after Guy Burgess, a friend of hers, had defected to Moscow as a communist spy, she told a former MI6 officer that Anthony Blunt, who was the surveyor of the Queen’s pictures, was a member of the Communist Party. The officer was aghast, but passed the information on. MI5 considered adding the information to Blunt’s file, but decided Budberg was too unreliable and rejected her intelligence. The decision was probably justified, since Budberg’s adherence to truth wasn’t always rock solid, but on this occasion she had the last laugh – or would have done if she’d lived long enough – as Blunt was exposed in 1979 as ‘the fourth man’ in the Burgess–McLean–Philby spy scandal that had rocked the British establishment in the 1950s.

There was a tiny frisson during Clegg’s appearance on the BBC Radio 4 programme Desert Island Discs in October 2010 when the presenter, Kirsty Young, put it to him that, in his role as Deputy Prime Minister, he was now in a position to get to the bottom of the rumours that Budberg had been a double agent. Clegg laughed genially, and then stopped, realising that Young was probably right. He quickly added, ‘Do you know, I prefer to keep it as a complete mystery.’ That answer also reflects the family’s wish for Budberg’s good sides to be remembered and for her to not just be made into a figure of fun or betrayal.

Budberg also developed her own technique for avoiding difficult questions in one particular television interview. She was asked a question she didn’t want to answer, so stared at the interviewer as if he hadn’t asked it and she was simply waiting for his next question. He asked his question again, and again she stared at him as if he hadn’t spoken. She was clearly keeping her dignity better than he was, and, getting somewhat flustered, the interviewer asked a different question, which she gracefully answered.

Budberg’s daughter Tania was also part of the Russian aristocracy in exile, living in south-east England for many years until her death in 2004. One of her publications was a memoir of her early life called A Little of All These, a title taken from a statement by the philosopher and travel writer Hermann Keyserling: ‘I am not a Dane, not a German, not a Swede, not a Russian nor an Estonian, so what am I? – a little of all these.’ It’s a title that could equally apply to Nick Clegg.

Kira, Budberg’s niece, married Hugh Clegg in the summer of 1932. He was at the time a sub-editor on the British Medical Journal, and went on to become one of the leading figures in the British medical establishment in the twentieth century. (He is not to be confused with another Hugh Clegg, a respected professor of industrial relations, who was also prominent at the same time.)

Hugh Anthony Clegg was born in St Ives, Huntingdonshire, in 1900, to John Clegg and Gertrude Wilson. John Clegg was a clergyman and school teacher from the East Riding of Yorkshire, who had migrated to Lowestoft. The Yorkshire connection is useful for Nick Clegg, who, although he could never claim to be a Yorkshireman, makes the occasional mention of his Yorkshire roots when in Sheffield visiting the affluent constituency of Hallam, which he represents in Parliament.

Hugh was the third of seven children, and the man who raised his branch of the Clegg family from the modest surroundings of a Suffolk parsonage to a source of leading figures in British society – both through professional aggrandisement and in marrying an aristocrat, albeit an émigré one. He gained a scholarship to Westminster School and an exhibition to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he went on to become a senior scholar in natural sciences. He missed service in the First World War by a few months – he was entered as an ensign in the Irish Guards, but the war finished too early for him to see active service.

He worked his way up the medical ranks, becoming an eminent doctor, and was contemplating a career as a general physician specialising in chests when he joined the staff of the British MedicalJournal as a sub-editor. Although he continued to practise, and did a lot of valuable work in London treating patients during the Second World War, his career was established on the ladder that would see him become one of the most significant mouthpieces of the British medical community. He was the editor of the BMJ from 1947 to his retirement at the end of 1965, but was effectively in charge for nearly thirty years; he became deputy editor in 1934 and, from the late 1930s, frequently had to stand in for his ailing boss, N. G. Horner.

With the foundation of the National Health Service in 1948, it was a momentous time to be the editor of a world-respected medical journal, and Hugh’s editorials were widely read. As such, any history of British medicine in the twentieth century must feature some mention of Hugh Clegg, but he had a rough character trait that, if not his undoing, perhaps prevented him from going as far as he might have done. Those who knew him said he was often tactless, if not downright rude, and his attacks on medics he disagreed with often became unnecessarily personal. A good friend from the medical world, Bradford Hill, said Hugh always regretted not making a career in clinical medicine, a step he felt unable to take because of a lack of finance resulting from his relatively poor background as one of a country parson’s seven children. Hill also believed the personal nature of Hugh Clegg’s attacks was largely responsible for him getting ‘only’ a CBE when he retired, as opposed to the knighthood given to his opposite number at the Lancet, Theodore Fox. Fox, Hill maintained, was better able to separate the subject matter from the personal when he disagreed with someone. In its obituary of Hugh Clegg in 1983, the BMJ pointedly said, ‘He was not one to let current events pass without coming to his own conclusions about them.’

But if that is a veiled reference to his forthright views, there’s no doubt that those in the medical profession couldn’t afford to avoid Hugh Clegg’s publication. He had taken the BMJ from a somewhat boring voice of the British Medical Association – more preoccupied with the BMA’s annual general meeting than with advances in medical research – to a highly respected journal, publishing a raft of statistics-based papers which were unfashionable at the time. He widened its accessibility by introducing summaries or abstracts at the start of all the leading articles, so people didn’t need to read everything, and when contributors asked him how long their article should be, he was known to reply, ‘As long as it has interest; stop when it has not.’ As a result, the magazine’s appeal widened to take in most British doctors and a readership well beyond the BMA.

Nick Clegg invoked his grandfather in a speech in early 2010 in which he railed against Britain’s libel laws. With the BMJ having recently declined to publish an article on child abuse for fear of it being defamatory, and a journalist, Simon Singh, being sued for libel after questioning the efficacy of chiropractic methods, the Liberal Democrat leader quoted Dr Hugh Clegg’s belief that ‘scientific debate is at its most robust, most fruitful, when it is conducted in public’.

Hugh and Kira made their home in the Buckinghamshire village of Little Kingshill, and had two children: Nicholas (Nick’s dad) and Jane. They eventually moved back to London, and were living in the capital when Nick and his brothers and sister were growing up in Buckinghamshire in the 1970s.

Slightly less colourful but arguably more dramatic is the maternal, Dutch side of Clegg’s family.

His Dutch grandfather was Herman Willem Alexander van den Wall Bake, known as ‘Hemmy’. A tall man, he studied at the Technical University in Delft, during which time he fell in love with a fellow student, Louise Hillegonde van Dorp, who he had met on a student boat trip (the Dutch van means ‘of’ but doesn’t denote the same degree of upper-crust breeding as the German von). She was studying English, but was also a very gifted musician, playing the piano to a high standard and doing very well at the violin. After graduating, Hemmy went to the Dutch East Indies, now Indonesia, to work for the Batavian Oil Company and later Shell. Much later, he became president of the Dutch banking giant ABN, and was reported to be a friend of the Dutch royal family.

Hemmy and Louise married in early 1932, and she followed him to the Dutch East Indies. For the first ten years of their marriage they were very happy, and had three children, all girls. The middle daughter, Eulalie Hermance, is Nick Clegg’s mother, born in November 1936 in Palembang.

The family was living on the island of Java when war broke out in early 1942. The Japanese, who were fighting on the side of the ‘Axis’ powers led by Germany and Italy, attacked the Dutch East Indies, hoping to capture the country’s rubber and oil supplies to aid the Axis war effort. With the independence movement gaining strength in its campaign to rid the area of its Dutch colonial masters, it was the start of a turbulent time in the history of the territory that was to become Indonesia.

When war broke out, Hermance was five. She remembers the air raid sirens beginning, which meant the family had to go into a bunker that heavy rain had turned into a huge puddle of mud. Louise used to give her girls a piece of rubber to put between their teeth, a saucepan for their heads, and cotton wool for their ears. After Japan had attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Hemmy was made a first reserve lieutenant in the Dutch cavalry, and was moved to a garrison in West Java called Batujajar. To be close to him, Louise and the three girls moved to a friend’s house nearby. But he was soon called up for action, and when the friend’s house was commandeered by the independence leader Sukarno, later Indonesian president, they were sent to a Japanese internment camp, Kramat. During the takeover of the house, Louise was kicked so hard by a Japanese soldier that she developed a tropical ulcer on her shin which never healed during the years of the war.

At first Kramat was an open camp, which meant Louise and her three girls were fairly free to come and go and life was just about bearable. But things got gradually worse, and fights frequently erupted over the dwindling supplies of food. Then on 23 August 1943, 2,500 women and children were forced to leave Kramat for Tjideng. Tjideng was another internment camp, just for women and children, set up by the Japanese in Batavia (now Jakarta). Over the two-and-a-half years Nick Clegg’s mother, aunts and grandmother were interned there, Tjideng developed a reputation for being one of the worst places in Asia. A survivors’ website describes it as ‘Hell on Earth’. Louise later told Hermance, ‘If we had been there one more month, you wouldn’t be here.’

Chapter 2

‘ALL ARE GUILTY OF SOME ATROCITY’

WHEN NICK Clegg talks about why he is ‘a liberal to his fingertips’, the influence of his mother, Hermance van den Wall Bake, is never far from his reasons. He talks about ‘her no-nonsense Dutch egalitarianism’, and in an interview with The Telegraph magazine he said, ‘My mum also retains a slight bemusement at the idiosyncrasies of the British class system, and I think that’s rubbed off on me too.’ But it is what Hermance, and his grandmother Louise, went through during the war – and the approach the family took to looking back on it – that has the biggest influence over his outlook on life.

Astonishingly, or perhaps not, Hermance hardly ever spoke about her war-time experiences with her four children. She finds it difficult talking about the war and says she doesn’t want to ‘pass on the fear’. Inevitably the subject would crop up from time to time, and she would occasionally mention her time in the ‘camp’, but the word meant so little to her children when they were young that they would sometimes say ‘Mum, when you were in those tents...’! As a result, stories of her war experiences seldom featured in discussions at home. ‘It would never have occurred to us to have asked her about it,’ says her eldest son, Paul.

Nick himself said on Desert Island Discs in 2010, ‘I’ve realised now, aged forty-three, how much she didn’t tell us – she sheltered us from a lot of those harrowing, harrowing memories. I think it strengthened my mum’s resolve to try and create the most happy, protected childhood for myself, my two brothers and my sister, and I think she succeeded, I mean we had an extraordinarily happy childhood. If you’re a young girl and you see people being beaten to a pulp in front of you, and being dragged off and shot, I can only imagine what that must be like for a child of the age of my oldest boy.’

In 2010, Hermance finally broke her silence, agreeing to give an interview about how she survived Tjideng to a Dutch magazine, De Aanspraak, a publication specifically for Dutch survivors of the Holocaust and the war in the East Indies. Paul Clegg says the four-page article that resulted from the interview contained more than twice as much as she had ever told her children about what she went through in the war. Of Tjideng she said, ‘There were seventeen of us in one house. My mother and sisters and I all had to sleep in one bed, with nine people to a room. We were constantly plagued by bedbugs, impossible to get rid of. Every day our ball rolled into the open sewer at the side of the road. My mother kept repeating that we had to wash our hands. It’s a wonder we managed to get out of it alive. At first there were 2,500 people in Tjideng, but we had to keep making room for a steady stream of new prisoners. By the end of the war there were 14,350 women and children in the camp. Although there was a lot of petty theft, there was also a feeling of solidarity. If one of the mothers got ill, someone would step in and take care of the children.

‘There were lots of times when the women panicked and some of them started to beat their children. The camp commandant, Sonei, was a cruel lunatic who made us stand on parade for hours on end, day and night, so we could be counted. We had to make a very deep bow, in the direction of Japan, with our little fingers on the side seams of our skirt. If we didn’t do it properly, we were beaten. The Japanese would lose count and were forever having to start again, but my mother always stayed very calm.’

Like other camps, Tjideng was initially under civilian administration, with a certain amount of freedom. It was when the military took over – in Tjideng’s case under the command of the despotic Lieutenant (later Captain) Kenichi Sonei – that things became desperate. Accounts from survivors talk not only of a massive growth in the camp’s population, but at the same time a gradual reduction in the amount of land on which the camp stood, which made the overcrowding much worse. Savage beatings and kicking were commonplace for the slightest misdemeanour; heads were shaved; doors and windows were burned for firewood, leaving no protection from the elements; and all boys over twelve – later reduced to ten – were sent to the men’s camps. All caged inside a fence of matted bamboo called gedèk.

‘Our worst fear was that we would lose each other,’ said Hermance in her Aanspraak interview, ‘so my sister and I were very worried about my mother’s tropical ulcers. She was covered with them because of a vitamin C deficiency. For her sake, we would go out early in the mornings and gather cherries that had fallen from the trees in the night. When the war ended she only weighed 36 kilos. Later, she would often say to me “If it had lasted one more month, you wouldn’t be here”. I was listless by that time and unable to eat anything at all.’

Perhaps more remarkable than the suffering was the attitude towards it. Hermance said her mother was keen not to get involved with any confrontation, often offering food to squabbling mothers to end a conflict, even if it meant she and her daughters became even hungrier. During the long days in the camp, Louise would say to her girls, ‘You have to learn to read and write – if you go to school in Holland in the future, you’ll want to be in the right age group.’ She read Alice in Wonderland in English with her eldest daughter, she made Hermance a dictionary for her birthday, and when she found her maths knowledge insufficient to teach the numerical skills she thought were necessary, she bought some lessons by bartering with baked sago starch, even if that meant less food for her and the girls.

Hermance says of her mother, ‘She was an exceptionally strong person with an enormously positive character. She never wanted to dwell on people’s weaknesses. She preferred to ignore the bad side, which is what she did in the camp.’ She recalls similar positivity from her father. ‘He taught me not to harbour prejudice against any race whatsoever, because all are guilty of having committed some atrocity in the past. He did not want to pass anti-German or anti-Japanese feelings on to his children, and neither did I, as nothing would be gained by it.’

Both Nick Clegg and his elder brother Paul say that their mother has come through her war-time experiences without bitterness and recriminations. ‘If you can do that after all she had been through,’ says Paul, ‘you have to have a very strong character.’

Just before giving the Aanspraak interview, Hermance spoke with her youngest son Alexander, Nick’s younger brother, with whom she had visited Tjideng on a pilgrimage two years earlier. She told him, ‘They want to know how my time in the camp affected your upbringing.’ Alexander replied, ‘We learned never to make a fuss about food.’

The end of the nightmare began on 6 August 1945, when the USA dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Hermance’s father was the first Dutch man back in the camp, telling the guards at the camp entrance, ‘Either you open the gate or I’ll drive straight through it!’ He didn’t recognise Hermance at first, as he had been away for more than three years and his five-year-old was now eight.

Attempts to live in a house owned by the Batavian Oil Company came to nothing, as the end of the war was the trigger for Indonesian freedom fighters to start attacking the Dutch. So the five of them were put in another camp, this one for families, and the girls sent to a temporary school. One day, Hermance and her elder sister witnessed a murder in the square in front of the school, watching the victim collapse in a pool of blood. As the situation became more tense, Hemmy took to sitting in front of his house brandishing an axe, just to send the signal that he was defending his family.

During a train journey from Batavia to Bandung, Dutch citizens were attacked by freedom fighters when the train went into a tunnel. Shots were fired, and women and children began screaming. People crammed into one end of the train, making it very difficult to breathe. Louise calmly told her daughters, ‘Stay very still and you won’t need so much air.’ They survived the ordeal, but knew then that they had to get out of the country.

They left on one of the first flights to the Netherlands via Cairo. While in Cairo, the Red Cross provided them with their first real food for several years. By the time they arrived back home, Hermance and Louise were in a terrible state, and spent about nine months convalescing. For several years, Hermance suffered from anaemia and inexplicable fevers, and despite her mother’s best efforts to keep her daughters at the same level as their contemporaries, there were times when Hermance just couldn’t keep up with children her own age.

As Louise recovered her strength, there was another addition to the family – she gave birth to a fourth girl in the early 1950s. Hermance meanwhile gradually caught up with her education, going on to train as a special needs teacher. At the age of nineteen, she wanted to brush up her English, so she went to Cambridge to do a language course, and while there fell in love at first sight with an Englishman called Nick Clegg.

The idea that no anti-German or anti-Japanese feeling should result from the appalling treatment Hermance had suffered at the hands of the occupying Japanese forces found expression in her marriage and her children. While all her children proved proficient in German (it was Clegg’s best learned language, certainly until he met his wife Miriam and became fluent in Spanish), her husband spent many years working with Japan, and was eventually awarded a CBE for services to Anglo-Japanese relations.

Nicholas Peter Clegg, Nick Clegg’s father, was born in London in May 1936, six months before the woman he was to marry. In 1940 he was sent with his mother (Kira) and his sister Jane on one of the last refugee boat convoys to America, spending time in New York, Long Island and Connecticut, before being allowed to fly back to Britain as early as 1942. He went to school in the West Country, first at a prep school in Port Regis and then at Bryanston.

Nick Clegg Sr did his national service in the intelligence division of the Royal Navy, during which time he learned Russian, and he was stationed in Germany and Cyprus. He then went to study international law and economics at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he met his bride-to-be. After graduating from Cambridge, he married Hermance, and worked for a while in London. Shortly after their first child was born, he took a job in the Netherlands with the Dutch steel works. Two years later he got a job with Procter and Gamble in Belgium, so the family, by then with two children, moved again. A further two years passed, before they moved back to England, setting up home in the Buckinghamshire village of Fulmer, where their third and fourth children were born.

From then, Clegg Sr pursued a career in banking. He was a director of the merchant bankers Hill Samuel (who were eventually taken over by Lloyds TSB), and later joined Japan’s second-largest securities firm, Daiwa Securities, first as managing director of their London operation, Daiwa Europe Ltd, then becoming co-chairman of the securities operation as well as chairman of their new bank, Daiwa Europe Bank. It was the start of a long relationship with Japan that continued until after his retirement. He helped conceive and establish the Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Foundation, a UK charity funded entirely by Daiwa to promote better understanding between the people of Japan and Britain by educational ‘cross-fertilisation’ initiatives, whereby Japanese students going to Britain would be given financial help, as would British students going to Japan. It is now arguably the leading organisation in its field, and it was doing this role, over more than twenty years, that earned him a CBE in 2009.

He also had various other roles in the banking world. He was a director of the International Primary Markets Association, he sat on the supervisory board of the Dutch bank Insinger de Beaufort, he was a senior adviser to the Bank of England on banking supervision, he joined the board of a Hungarian bank, and was an adviser to a bank in Brazil. On retirement, he became non-executive chairman of the United Trust Bank, a relatively small bank which describes itself as one of Britain’s leading suppliers of funding for UK-based property developers. He remains in that role today.

With the performance of the banks a major issue in the two years leading up to the general election of 2010, the media enjoyed speculating on whether the Liberal Democrat leader’s paternity was likely to make him tackle the banks with the same vigour that went into his speeches on banking. On a couple of occasions, he invoked the name of his father as an example of ‘good old-fashioned banking principles’, and said his dad was furious at the behaviour of today’s banking community. It’s hard to know whether Clegg is likely to be more understanding of the banks because of his father’s background, or more contemptuous about the absence of noblesse oblige in the way modern banks have behaved. Ultimately, it probably doesn’t matter, as the pragmatics of getting big money to stay in Britain (and thus to pay significant amounts of tax) are always likely to win out over the kind of pre-election statements that will appeal to voters, or even the best of intentions.

Certainly, some of Clegg’s political foes have made a little mischief over his dad’s banking background. Speaking to Channel 4 in the run-up to the 2010 election, the Conservatives’ then business spokesman, Kenneth Clarke, said Clegg should have followed his father’s ‘political wisdom’. Clarke worked with Clegg Sr for a year at Daiwa Securities, and describes him as ‘a very nice, very wise man’. The dig at Clegg Jr was that his dad was a Conservative, but even in that, Clarke didn’t seem entirely sure. ‘He was a very successful City man,’ Clarke told Channel 4, ‘but he wasn’t a flash City man in any way. He was a Tory, I think, quite definitely.’ How definite Clarke can be is a little uncertain. He clearly assumed the banker was a Conservative, but the Clegg children never knew how their parents voted. ‘We knew it wasn’t Labour,’ says Paul, ‘but we never knew if it was Conservative, Liberal or anything else.’ And Nick says his folks were ‘small-L liberals’, though that also says nothing about which way they voted. The only certainty was that Kira was a long-time supporter of the Liberal Party.

Like their respective parents, Nick Clegg Sr and Hermance van den Wall Bake (she uses the name ‘Clegg’ in Britain but largely goes by her maiden name in the Netherlands) are clearly ‘defined’ people. David Brown, who became housemaster to Clegg at Westminster School, recalls being invited back to the Clegg house as part of getting to know the parents of the boys he was in charge of. ‘What I remember most about the Cleggs’, he says, ‘was the very nice mum – very bright, broad minded, intelligent, supportive, so that is probably one of the many reasons why we didn’t have any trouble with him. Nothing against the father, who was also very nice – in fact I have kept a letter Nick’s father sent me – but the mother stands out more. Nick came from a very strong home life.’

While Clegg Sr pursued his banking career, Hermance mixed raising a family with her career as a special needs teacher. She taught dyslexic children, starting in Montessori schools. Having witnessed her mother’s fear that the window for learning can sometimes be quite small, she was keen to find the right approach to releasing what she has always felt is the huge amount of potential that lies in all young people. ‘She believes passionately in children,’ says Paul, ‘and if you look at Dutch society, it’s very family oriented, not just now but going back hundreds of years. She exemplifies that in many ways. She’s a very natural teacher.’

Shortly after Nick Clegg Sr retired at the age of sixty-two, he and Hermance bought a badly run-down French farmhouse, the idea being to renovate it as a labour of love. Set amid rural farmland in Charente-Maritime, south of the Cognac region, it is a rambling building with a fair bit of space both within the house and also in the form of outlying sheds and barns. ‘We really wondered if they would have enough energy to do it,’ says Paul Clegg.

They did have enough energy, plus enough money to buy in specialist help when needed. The house is now in much better shape, and acts as a venue for occasional gatherings of the Clegg clan. It also acts as a stick with which the less Lib Dem-friendly sections of the British press can beat Nick Clegg – in an article published two weeks before the 2010 general election, the Daily Mail described the French farmhouse as ‘a chateau’. Few, it must be said, are lucky enough to own a second home, and the house does have enough space to put down a fair few camp beds, but some elegant Louis XIV chateau in the Loire it is most assuredly not.

The Cleggs have access to another house, a chalet in Switzerland that came through the Dutch side of the family. Clegg’s grandfather, Hemmy, built it in 1962, and it provided the venue for a number of family holidays. When Hemmy and Louise died, it passed to Hermance and her three sisters and remains their joint property. Again, it didn’t stop the Mail saying Clegg comes from a family with ‘a chateau and a chalet’ – at least the alliteration is attractive, even if factually it’s stretching a point.