Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Upstart

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

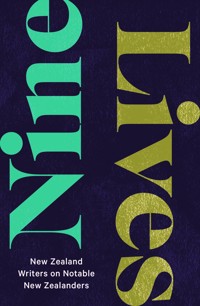

A selected group of NZ writers have chosen a favourite New Zealander to write an essay on. These pieces are personal, illuminating and often moving. Around 5,000 words per essay, the writers had full choice on who to write about and what approach to take, so there is great variety in the styles. Writers are; Lloyd Jones on Paul Melser (potter), Paula Morris on Matiu Rata (politician), Catherine Robertson on Dame Margaret Sparrow (doctor and health advocate), Greg McGee on Ken Gray (all black), Stephanie Johnson on Carole Beu (bookseller), Malcolm Mulholland on Ranginui Walker(academic) Selina Tusitala Marsh on Albert Wendt (writer), Elspeth Sandys on Rewi Alley (writer and activist), and Paul Thomas on John Wright (cricketer).

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 229

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Introduction

Catherine Robertson on Margaret Sparrow

Lloyd Jones on Paul Melser

Selina Tusitala Marsh and Pala Molisa on Albert Wendt

Paul Thomas on John Wright

Elspeth Sandys on Rewi Alley

Stephanie Johnson on Carole Beu

Malcolm Mulholland on Ranginui Walker

Paula Morris on Matiu Rata

Greg McGee on Ken Gray

About the authors

Introduction

Nine Lives. We asked our authors to provide an essay on a notable New Zealander of their choice. Some subjects are well-known, others not, but the essays are all far from dry, dispassionate potted biographies. In inspiring, intriguing studies, the writers take a fresh look and provide unexpected insights, with views of their subjects often at odds with the mainstream.

Once we had the essays, we decided the order by drawing lots. The writers, on the other hand, haven’t chosen randomly. There is a relationship. Some subjects are blood relatives, or they are in the same field of endeavour. There are striking parallels. These are often deeply personal accounts, with the lives of author and subject intertwined, and the experiences of the subject have influenced and shaped the writer’s own journey.

Writers and subjects alike reflect some of our rich diversity, and all add meaning to the experience of life in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Enjoy.

Upstart Press

After my twenty-first birthday and before the advent of seven-digit phone numbers, I was given a local anaesthetic and a foetus was aspirated out of my womb.

The abortionist was Dr Margaret Sparrow. She resembled her name, small and fine-boned, not an ounce of fat. A puff of wind would blow her away, my mother might have said, but I found Dr Sparrow intimidating. Her manner was formal. She did not smile and delivered the necessary information to me with a cool detachment. I assessed her age as very old (she was fifty-two), and I knew nothing about her except that she worked here, at Parkview Clinic, and had appeared on TV advocating for a woman’s right to choose. I thought feminists were aggressive and abortion was only for girls who’d been stupid. I lay on the operating table and Dr Sparrow did to me, ‘within the framework of New Zealand law’ what she had done illegally to herself when she was my age.

In her book Abortion Then & Now,1 Margaret Sparrow describes 1956 as ‘an eventful year. In chronological order, I was married, was nearly killed in a car crash, graduated BSc, had my first job as a research assistant, turned 21, got pregnant, and had an abortion.’

There is a photo of young Margaret at her graduation ceremony at the Wellington Town Hall. Her academic gown falls over a shimmery formal dress. She holds her degree scroll and a posy of flowers, and she is gorgeous, bright-faced, smiling. ‘You are looking at a criminal,’ she tells us.

Except on medical grounds, abortion is a crime warns a 1944 advertisement from the Department of Health. Inducing your own abortion could see you sent to prison for up to seven years. In 1937, the McMillan report on abortion estimated that 6000 abortions — one in five pregnancies — were performed in New Zealand every year, and of those, 4000 were illegal. We had one of the highest death rates from abortion in the world.

The 1944 advertisement puts the number of illegal abortions at 4600 a year. Government officials chose not to consider why women might want to have an abortion but decided instead to shame and frighten them: This is a threat to the future of our nation. Every woman who lends herself to criminal abortion risks sterility, sepsis and death. The advertisement’s last words are: Let the new life be born!

Near Paraparaumu, there’s a sign on someone’s outbuilding. It has been there for over fifty years, since I was a child. It says Abortion stops a beating heart. The Society for the Protection of the Unborn Child with its acronym like an angry spit, SPUC, was formed in 1970 and anti-abortion protesters used to hang around the entrance to Parkview Clinic. There’s a press photograph of a group in 1989.2 A nun holds a placard that says Nobody dies here today. A man sits behind an image captioned 8 week pre-born baby. At eight weeks, a foetus is the length of a kidney bean and resembles a tadpole. The foetus in the image is recognisably a baby.

When I arrived at Parkview, I saw no protesters. But then, I don’t remember how I got there. By taxi, most likely; my mother and my boyfriend were both at work. The entire visit appears to me in a series of images, a slide show on an old projector. Whirr-click — the blue vinyl chairs in the waiting room; I’m in a corner nearest the window that lets in only a little light, the rest of the room appears to be in darkness. Whirr-click — my notebook; I’m writing a humorous article about jeans for the magazine I work for, my boss, the editor, is always scrambling to meet tight deadlines and she needs this piece done. Whirr-click — Margaret Sparrow’s face bending over me; I’m on the operating table. The clinic’s information form says my feet may have to be in stirrups. During the operation I must lie with my legs open.

Some certifying consultants appear to be of the view that it was a waste of their time to perform abortions when women were not prepared to take responsibility for preventing an unintended pregnancy.3

Margaret and her husband Peter were studying medicine in Dunedin. When they married, Margaret’s student living allowance was withdrawn because husbands were expected to provide for their wives. They barely had enough money to cover their own living costs.

The newly-weds had been using the most common contraception available — a diaphragm. To have it fitted, Margaret needed to provide proof that she was going to be married. Single women could not be prescribed contraception; it was considered unethical. She and Peter were too poor to afford an engagement ring, so she cut out her marriage notice from the Fendalton Parish magazine and took it along. The diaphragm failed. Margaret was pregnant.

‘The first thing you do is all the silly things,’ she told a journalist in 2015. ‘The old wives’ tales — jumping, skipping, exercise. Then I took a bottle of DeWitt’s Pills. All that did was turn my urine blue.’4

DeWitt’s Pills were supposed to cure aches, pains, restlessness and loss of energy caused by sluggish kidneys. They contained Pot. Nit., Salicylamide, Buchu, Methylene Blue, Uva Ursi, Caffeine Alk.

Peter, Margaret’s husband, knew of a chemist in Christchurch who sold ‘personal products’ by mail. This was George Bettle, Everybody’s Chemist, as it said in his advertisements. The bottle arrived in a brown paper bag. Its typewritten label simply said: ‘The Mixture. Take one tablespoon full three times daily.’ Margaret took her medicine and had an early miscarriage.

When I was a child, I took a medicine called The Mixture. Our family doctor, long since dead, concocted a bottle of red syrup that he doled out for coughs and colds. Much later, we found out that it was packed with codeine. George Bettle knew what was in his own Mixture but those who took it did not. Abortifacients have been ingested by women for as long as people have recorded such remedies. In the eleventh century, Hildegard von Bingen’s Liber simplicis medicinae recommended tansy to restore menstruation, and a herbal of the day listed rue, soapwort, black hellebore and the botanical that persisted, pennyroyal. Two tablespoons of pennyroyal essential oil killed a woman in Colorado in 1978. In the twentieth century, women were desperate enough to down turpentine, detergent and, presaging Covid-quackery, bleach. If the remedies by mouth did not work, solutions of soap, disinfectant, turpentine were squirted into the uterus. Potassium permanganate, a chemical compound developed in 1857 as a disinfectant, was placed in the vagina.

When Margaret induced her own abortion, New Zealand followed British law, set in 1938 when the case of R. v Bourne decided that a fourteen-year-old girl who’d been raped would be mentally damaged if she was forced to have the baby. The judge stated that a doctor could justify performing an abortion if they were certain that ‘the probable consequence of the continuance of the pregnancy is to make the mother a physical or emotional wreck’.

A physical wreck. Potassium permanganate in the vagina caused severe chemical burns. Oral remedies led to kidney failure and poisoning. Douching caused death by air embolism, with heart stoppage due to cervical shock.

Some of the young women who came to George Bettle for help said he sexually assaulted them. He committed suicide in 1964 while on remand for a charge of supplying the means to procure illegal abortions. He brought about his own death by drinking a bottle of poison.

Margaret had no side effects from George Bettle’s Mixture other than the early miscarriage. She did not have to resort to finding an illegal abortionist. She did not have a knitting needle, bent coat hanger, crochet hook, twig, ballpoint pen, chicken bone or bicycle spoke pushed through her cervix. No rubber catheter, bicycle pump nozzle or enema syringe. She was not at risk of dying of gas gangrene poisoning or toxaemia from peritonitis caused by a septic abortion. Before antibiotics, once you went into septic shock, there was no hope. The women could not breathe, they haemorrhaged, their organs failed. By 1956, antibiotics had greatly reduced the death rate but only if the woman sought medical help early enough. Abortion was not only illegal but also carried such social stigma that, as Margaret said, ‘We didn’t talk about it even to best friends.’5 A young woman who died from a botched abortion in 1959 never told her parents that she was pregnant. They wished she’d felt able to confide in them.

When I realised I was pregnant, I told my mother. My father was an odd man and we weren’t close. Besides, he would have had no clue what to say or do. My mother had problems of her own. She was two years away from leaving my father and had not had emotional time for me since I was thirteen. But this is a story for another day. When I told her, my mother was surprised — I was a quiet rule-follower, had never caused any trouble. I’d been sexually active since I was sixteen and had never had any ‘accidents’. My boyfriend was a nice young man, but he and I had been going out less than six months. We were only twenty-one, said my mother. I’d have to quit my job, and my boyfriend was still at university. Surely, we could not manage — emotionally or practically — a baby in our lives. She wouldn’t press us, however. It was up to us. Up to me.

My mother hadn’t been there for me for years, but she came through in that moment. I made a decision.

By 1987, abortion was ten years’ legal. Despite protests that included an MP waving a bottled foetus around the parliamentary debating chamber, the Contraception, Sterilisation, and Abortion Act passed in December 1977. Women now could legally get an abortion provided certain criteria were met. Seems there’s always a ‘provided’ when it comes to women’s health.

Time and the capacity of the mind to suppress certain memories mean I remember very little about what came next, but this was the process I must have gone through. First was a visit to a GP. My doctor was a woman, pragmatic and efficient. She confirmed that I was pregnant and how far along, and besides the usual enquiries, did not question my decision to have an abortion. She referred me to Parkview Clinic, where I would first have seen a social worker who would have interviewed me about my medical history and forwarded those notes to the two certifying consultants, more doctors, whom I would have seen one after the other, and who were responsible for final approval of the abortion. I have no recollection of these people at all. Margaret tells me that the certifying consultants were most likely two of the male doctors who worked at Parkview, although there were a few women consultants, too. ‘The staff tried not to make a big thing about it — to most of the women, it would have felt like a normal doctor’s appointment,’ she says.6

The law stated that before the consultants could approve the abortion, an operating surgeon had to be available. My surgeon was Dr Margaret Sparrow. I remember meeting her. In some clinics, the process was quicker because the certifying consultant and the operating surgeon were one and the same person. But Margaret had refused to be registered as a certifying consultant: ‘I’d stood up in public and said the system was all wrong, so how could I take people’s money in that way?’7 In 1998, Margaret was made redundant. Efficiency experts decided she had to be a certifying consultant and when she declined, she was let go. From the clinic she herself had helped found, eighteen years before.

In 1987, the most common method of abortion was vacuum aspiration:

The simplest method … the safest and most reliable. The procedure is relatively painless, most women describe the sensation as discomfort only, some say it is like their usual period feelings. There is no need for a general anaesthetic.8

Parkview Clinic provided an information sheet detailing every step of the procedure: internal examination; tranquillising injection; swabbing the vulva with antiseptic; insertion of a speculum. The doctor uses an instrument to take hold of your cervix and keep it still while she injects a local anaesthetic into it in two or three places. Area numbed, the doctor uses a curved metal dilator to slowly stretch open the cervical canal, the passage to your uterus. Dilation can take up to two minutes and can feel like heavy menstrual cramps. Once dilation is complete, the doctor inserts a cannula like a plastic straw attached to the vacuum aspiration machine. ‘You will hear the machine being turned on — it makes a humming sound.’ By moving the cannula gently around, the doctor empties the uterus of foetal tissue. Aspiration takes from two to five minutes. You are given a sanitary pad to put on and shown to a recovery room to rest quietly for an hour or so. You may feel good and very relieved, or you may feel weepy for a short time.

‘There is a risk of infection,’ Margaret had told me. ‘But it is very slight.’

At twenty-one, I was ignorant of all she had done to make this day possible for me. I regret not knowing more at the time; it would have reassured me. This woman had fought fiercely for longer than I’d been alive to give women more autonomy over their bodies, more choices about their reproductive future. I could not have had anyone more committed or qualified to perform my abortion.

Margaret June Muir was born in 1935 and grew up on a Taranaki dairy farm. Farmers’ daughters usually went on to become farming wives, but Margaret won a scholarship to study science at Victoria University. A BSc was followed by a car crash and a fractured pelvis that laid her up in hospital for twelve weeks. ‘I lay there between two sandbags.’9 She had been about to start her degree in medicine, but by the time she was discharged, the academic year was well under way. Margaret took a job as a research assistant to Otago University’s Professor of Surgery, Michael Woodruff, world leader in the field of organ transplantation.

This was the ‘eventful year’ of 1956: car crash, marriage, self-induced abortion. The year after, Margaret and her husband Peter were both studying medicine at Otago University, Margaret one of ten women in a class of 100. It took her seven years to complete her MBChB, because two of those years were spent at home with her toddler son and baby daughter. If feminism did not lead Margaret to demand Peter share the childcare, it did lead her to become one of the first women in New Zealand to take the oral contraceptive pill. Peter had a student placement with a GP and took the free samples home. This early pill, Anovlar, was the result of research by a Belgian chemist, Ferdinand ‘Nand’ Peeters, and was the first oral contraceptive with ‘acceptable’ side effects. Anovlar was two-thirds higher in oestrogen than modern pills, but Margaret experienced none of the weight gain and headaches that put other women off taking it. The pill was ninety-nine per cent effective and she did not have another unplanned pregnancy.

Sparrow (1980) reported that 50 per cent of a sample of 100 women who attended Parkview Clinic for an abortion had been using no form of contraception at the time of conception … of the remaining 50 per cent, all of whom used some form of contraception, human error or less reliable methods, had contributed to contraceptive failure.10

When I got pregnant, I was on the pill. Our old family doctor, the one who doled out the codeine-rich Mixture, put me on it when I was seventeen at the request of my mother. I’d been sexually active for over a year, but Mum did not know this or, rather, chose not to know it. I took the pill every day but one week, when I was twenty-one and with my nice young boyfriend, I got lazy, or curious, or rebellious, and I skipped a couple after my period had ended. It could have been safe — the risk was technically low. It wasn’t. Did that count as human error? It was almost intended, but not quite. I didn’t tell my doctor about the skipped doses. She said the pill had a one per cent chance of failure. I was unlucky.

My boyfriend was Catholic. I was of no religion. I went to church with him once, after the operation, and the priest’s topic for his sermon was exactly that, as if he knew we were coming. Even the more liberal Pope Francis believes that ‘Human life is sacred and inviolable’.

We stayed together for another year after the abortion; there were other reasons why we eventually broke up. He asked me, perhaps a decade later, if I ever thought about the baby we might have had. We had never discussed it, not once. Of course I did, I told him, but I could feel sadness and also have no regrets.

You may feel very relieved, or you may feel weepy for a short time.

Margaret and Peter separated. They never legally divorced. In 1969, Margaret took a job with her alma mater, Victoria University, at the student health service. That year, a judge in Melbourne broadened the definition of when abortion could be considered legal to include physical and mental factors outside ‘the normal dangers of pregnancy’ that could jeopardise the woman’s health. Women from New Zealand who could afford air tickets could fly to the state of Victoria for a legal — and significantly safer — termination.

At Victoria University, the student association welfare officer did his best for young women who came to him in despair after Margaret, in her official paid position, had to turn them away. ‘I wasn’t about to refer them to Australian doctors I didn’t know were reliable.’11 But shame proved a quick motivator, and Margaret began to help by providing pregnancy tests — one young woman had travelled all the way to Melbourne only to find she was not pregnant after all — and prescriptions for antibiotics to prevent infection, so they wouldn’t have to pay for drugs in Australia.

But it didn’t take her long to realise that these measures weren’t helping that much. An ally came in the perhaps unexpected form of the Samaritans. ‘They were not anti-abortion,’ says Margaret. ‘The directors were empowered to do what they considered right.’12 This work was always done discreetly, to the point where Margaret’s main contact was known in correspondence only by the code name D16. D16 gave Margaret lists of reputable abortion providers in Melbourne and, from 1971, Sydney.

So began decades of practical activism. Margaret trained with Family Planning and formed a connection that endures; she is a Life Member and Honorary Vice-President. She joined ALRANZ, the Abortion Law Reform Association of New Zealand, in 1973 and was president twice, holding that role for a total of twenty-seven years. She was present in Parliament to witness the passing of the Contraception, Sterilisation, and Abortion Act in 1977 — and despaired at its lack of foresight and basic humanity. Abortion could be carried out within the framework of New Zealand law provided certain criteria were met. But it remained in the Crimes Act. It was still a criminal, not a health, issue.

Margaret helped set up Parkview Abortion Clinic in 1980. ‘It is all very well to campaign in favour of abortion,’ she said, ‘but the most political act for me was to be in the theatre actually doing the operations.’13

Protesters camped outside practically every day. People yelled ‘murderer’ at her when she drove in and out. A protester was arrested at Parkview and he insisted that Margaret testify at his trial as a hostile witness. ‘I was forced to stand up in court and explain what I did.’ The experience, the defendant’s supporters showing up to subpoena her — ‘that was the worst thing’.

Others came to her house and hammered crosses into her garden. They handed leaflets to her neighbours, informing them that their house prices had fallen because of their proximity to an abortionist. One quick-acting neighbour prevented a truckload of wet concrete being poured onto Margaret’s driveway.

Margaret shared stories of harassment in her submissions in support of recent changes to abortion legislation. On 18 March 2020, the third reading of the Contraception, Sterilisation, and Abortion Amendment Bill was passed. But at Select Committee stage, in a voice vote late at night, the section on safe spaces around abortion clinics was lost. Someone should have asked for a full count. No one did. In an attempt to remedy this error, MP Louisa Wall drafted a Private Member’s Bill, which was drawn from the ballot and introduced to Parliament. It passed its first reading in March 2021 by 100:15. Those who voted against cited protesters’ right to free speech.

In the National Library’s archive, there’s a photo of a man holding a sign with a crude drawing of a knife dripping blood and the words Cruel and vicious killers. Spare your baby from this but kill yourself.

In 1987, abortion was still in the Crimes Act. That year, there were 8789 officially reported induced abortions, up from 5945 at the start of the decade.14

There has been a slow but steady increase in the number of abortions performed in New Zealand over the last decade … Although the reasons given for this are speculative, some or all of the following are almost certainly contributing factors: the service has become more visible and more acceptable; the economic downturn and increasing unemployment (especially in rural areas); word of mouth satisfaction with the service; an increasing number of Maori and Pacific Island women seekingabortion …15

A report that, amazingly, came out the same month I had my abortion looked at how equitable abortion services were in New Zealand. Their conclusion — not at all.

Most abortions were carried out in the main centres of Wellington, Auckland and Christchurch. Women who lived outside them ‘were forced to travel, and bear the expense’. They might have children who needed care that they couldn’t find or afford. They might have a job with no time off. They would have to make up a story about why they were going away. They would have to lie.

My certifying consultants made the whole process so simple that I don’t even remember them. But grounds for abortion approval were open to individual interpretation:

Some certifying consultants thought that their colleagues were being too lenient, and that that criteria needed to be more stringent. This was expressed forcibly by one certifying consultant: ‘… The majority of abortions are done for social reasons dressed up to be mental problems … there is no reason why a fit 18 or 20 year old woman cannot have a child’.16

I had no problem getting access to abortion services. I had a sympathetic general practitioner. Parkview Clinic had both certifying consultants and operating surgeons on staff, when in some places, the resignation of a certifying consultant could bring the whole service in that area to a halt. I lived in Wellington and could have walked to Parkview if I’d wanted to.

I was one of the lucky ones.

Following an abortion, it is necessary for a woman to return to her general practitioner for a check-up. This would normally be about five days after the operation.17

In March 1987, I turned twenty-one. I’d graduated from Victoria University with a very average BA in English Literature. With some idea that I wanted to get into advertising, I applied for and got a job selling it. My employers were husband and wife. They published tourist brochures and a free monthly magazine, a smaller, flimsier Wellington version of Auckland’s Metro. The wife was the magazine editor and was constantly in a flap. It wasn’t uncommon for one of us employees to be thrown the car keys and sent to pick up the editor’s four-year-old daughter from childcare. The centre was, we gathered, on the verge of kicking the child out if her mother was late to collect her one more time.

My first job with them was selling advertising space in a tourist brochure. At the start, I was very bad at it. I did improve, but what I wanted to do was write. Three months in, they hired a better salesperson and let me write full-time — advertorials and feature articles. I also collected galleys from the typesetter and did paste-up with a Rotring pen, hot glue and scalpel. Later, we’d get a Macintosh computer and desktop publishing software, and I would ‘design’ ads. We all had to pitch in because we were always running late. The editor was not a terrible person by any means, but she was terrible at time management. I sat in the Parkview Clinic waiting room and wrote a humorous story about jeans because we were on deadline.

There is a risk of infection, but it is very slight. I tell Margaret I recall her citing a figure of around four per cent. ‘Certainly under ten per cent,’ she confirms.

The abortion procedure was, as the information leaflet promised, uncomfortable but not painful. I went home to my flat — no idea how. The next morning, I was supposed to go in to work, but I’d been woken early by cramps in my abdomen and a hot feeling all over — I had a fever and felt weak and exhausted. I phoned work to tell them I wouldn’t be coming in. ‘You have to!’ said my boss, the editor. ‘We’re getting the magazine out — we need everyone on deck!’

I was bleeding, too. Quite a lot. I packed extra period pads and caught the bus to the office.

The cramps got worse. I went to the women’s toilets and expelled great gouts of blood and clots. When I came back into the office, a concerned co-worker asked if I was all right. I told her. She made me ring my GP. My doctor, normally calm, practically yelled at me. ‘Go to the hospital right now! Go directly to A&E. I’ll tell them you are coming.’

My co-worker offered to drive me, but my boss said no, she couldn’t be spared. I caught a taxi to Wellington Hospital, where they admitted me straight away. Under general anaesthetic, my uterus was scraped free of septic remains. An intern tried to put the needle for the drip into the back of my hand and messed it up. I had a bruise for weeks. My mother took me back to my childhood home and put me to bed. My boss visited to apologise and give me a bottle of perfume. I don’t remember my boyfriend coming to visit, but he must have. He was a nice young Catholic man.