Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc.

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

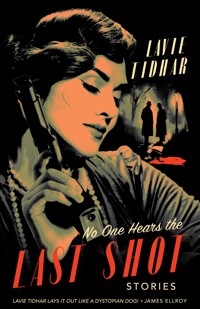

"Lavie Tidhar lays it out like a dystopian dog!" —James Ellroy A middle-aged hitwoman goes on the run from the Israeli mob; a boy on a South Pacific island searches for a missing cat and uncovers dark secrets; an ageing bagman has to recover a package across one violent night, no matter the cost; an informer must uncover the heist of a lifetime on the fringes of the Roman Empire, and Sherlock Holmes is faced with a confounding botanical mystery; while a pair of hapless actors are forced into a seedy mystery in Golden Age Hollywood. Moving from the genteel English countryside to the mean streets of L.A. and from the islands of Vanuatu to the dark alleyways of Tel Aviv, this wide-ranging collection gathers together the best crime and noir stories of master storyteller Lavie Tidhar, including the CWA Dagger Award nominated "Bag Man" and much more besides. Welcome to a world of gangsters and hired killers, of lost romantics and deadly women, of good times and lowlifes. Where it's always the wrong part of town, and where whatever you do, there are no good choices... Because when it comes, no one hears the last shot. "Tidhar changes genres with every outing, but his astounding talents guarantee something new and compelling no matter the story he tells." —Library Journal "Some write in ink, others in song, Tidhar writes in fire." —Junot Díaz

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 283

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

No One Hears the Last Shot

Copyright © 2025 by Lavie TidharAll rights reserved.

Published as an ebook in 2025 by JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc. in conjunction with the Zeno Agency LTDOriginally published by PS Publishing in the U.K. in 2025

“The Bell” first published in Invisible Blood, ed. Maxim Jakubowski, 2019

“The Mystery of the Missing Puskat” first published in Chizine, 2008

“The Temple’s Coin” first published in The Book of Extraordinary Historical Mystery Stories, ed. Maxim Jakubowski, 2019

“Bag Man” first published in The Outcast Hours, ed. Mahvesh Murad and Jared Shurin, 2019

“The Adventure of the Milford Silkworms” first published in The Book of Extraordinary Historical Mystery Stories, ed. Maxim Jakubowski, 2020

“Hava” first published in The Book of Extraordinary Femme Fatale Stories, ed. Maxim Jakubowski, 2022

“The Case of Baby X” first published in Black is the Night, ed. Maxim Jakubowski, 2022

“Red Riding Hood”, “Raskol” and “The Last Romantics” first published by PS Publishing in 2025

Cover art © by Sarah Anne Langton

All rights reserved.

ISBN 978-1-625677-99-0 (ebook)

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places and events are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc.

49 W. 45th Street, Suite #5N

New York, NY 10036

http://awfulagent.com

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Title Page

Copyright

1. The Bell

2. The Mystery of the Missing Puskat

3. The Temple’s Coin

4. Bag Man

5. Red Riding Hood

6. The Adventure of the Milford Silkworms

7. Raskol

8. Hava

9. The Last Romantics

10. The Case of Baby X

Story Notes

About the Author

Also by Lavie Tidhar

THE BELL

1.

“I told him, of course I know how to use a gun. Everyone knows how to use a gun. He was very cute though.” In the booth next to hers, two girls of about nineteen had their rifles resting against the changing room’s wall as they tried on lingerie, hurriedly. “Did you sleep with him?”

“We made out. What time is it?”

“The bus is in half an hour.”

“I don’t know about sleeping with a German,” the one girl said, dubiously. Deborah could hear the girls through the thin walls of the changing rooms. She checked her own watch. The girls had Tavor assault rifles, semi-automatic. Deborah looked in the mirror but the blouse sat on her like a sack. She checked her own watch. Deborah had a Jericho pistol, 9mm, stolen from an IDF army base a year and a half back. She looked at the blouse again and sighed and began taking it off.

“Do you really want to screw a German? I mean my mum won’t even go to Germany or use a German car. Because of the Holocaust.”

“Well, he’s cute.” She could hear them changing, the heavy army boots pulled back on their feet. The guns lifting from the wall. “Are you going to get that? Wait what are you doing?”

“Just act natural,” the other girl said. Deborah heard her stuffing something under her uniform. The door opened and the two girls left.

Deborah looked in the mirror again. Should she buy it anyway? She couldn’t decide. She checked the watch. It was almost time. She left the changing room and caught sight of the two young soldiers disappearing through the doors of the mall. She thought about crime, small white crime like stealing a pair of thongs or a bra, or selling a matchbox of hash, or killing a man. There was a scale for crime, but wasn’t it all transgression when it came right down to it? It was all a form of stealing, whether you stole a garment or a breath or a life.

The gun had been nestled patiently at the bottom of her bag. She had let the elderly Russian security guard check her bag on entering the mall, but the examination was cursory, indifferent. He wouldn’t remember her. What was there to remember? The important thing was not to draw attention and be quick and stay away from cameras. She went to the busy food court where the men were sitting at a table in the middle together, keys and phones on the table, cigarette packets and disposable lighters, plastic coffee cups and trays with shawarma and humous and chips, pickles, salads. She waited. Presently the man she had come to see got up and made his way towards her. He passed her and she followed him to the sign that said Toilets, through fire-doors into a corridor. A man came out of the Men’s wiping wet hands on his jeans. She waited for him to pass. Aharoni had his hand on the door when she said, “Excuse me,” and he turned, looking at her without really seeing her, a little bemused at this middle-aged woman in the shapeless blouse with the anxious face, “Listen buba, whatever you’re asking for I already gave and I got to take a piss.” Then his eyes grew just a little bit wider when she took out the gun and shot him twice, quickly, in the face. Do you see me now, she thought. Aharoni fell back against the toilet door, which swung inward, and his body fell on the toilet floor smearing blood and brain on the door-handle, on the door and on the floor someone must have just cleaned, an Arab or an Ethiopian, someone as unremarkable as her. She only took one look, to make sure, but she was already walking past and out, not hurrying, the gun safely in her handbag.

“I think I’ll take this,” she told the girl behind the counter back in the shop. The girl rang the top through. There was a commotion behind her. “Thank you.”

“Would you like a bag?”

“Thank you, yes.”

She took her shopping and left the mall. There were police sirens in the distance as she left, growing closer.

2.

It all began with Rafi, always Raphael to her but Rafi to his friends, of which he had many, though none of them were any good. When he was little he was so scared of everything, Deborah used to have to hold him night after night and rock him to sleep. His dad, Soli, died when Raphael was five. Not in the army, for which, at least, there would have been a pension, but in a stupid traffic accident, coming off the Ayalon interchange in someone else’s car. She’d met Soli after the army, they were married a year later in Tel Aviv when Rafi was already kicking in the womb.

“But I didn’t think you’d be in, Ima,” he said. She had walked in to the small flat and there was her son, so thin now, his T-shirt ill-fitting and grey, standing in the middle of her living room riffling through her things. “Raphael, I have nothing left to take,” she said. Then she saw he was holding the gun and she said, “Not the gun, Raphael, it’s not yours to take, it belonged to your father.”

“But he’s dead,” the boy said, with sudden savagery. His eyes were milky, pale, and he was shaking.

“Put it down.”

It was an old gun, a Star 9mm, a Spanish knockoff of a Colt, not manufactured since the nineteen sixties. She didn’t know who Soli had bought it from but he’d never used it. She had forgotten it was even there. “I could sell it,” Rafi said; but she could see the fight was gone from him.

She gave him two hundred shekels, it was all she had, and he left. He crawled back two days later, leaving a tooth and a trail of blood on her kitchen floor. The money had not been enough. It would never be enough. She made chicken soup and fussed over her son, who lay shivering on the couch. “Who did this to you?” she said.

“Leave it, Ima. It’s nothing.” She touched his bruised ribs with a wet dishcloth and he flinched. “This is nothing?” she said; but the boy did not reply.

She made chicken soup: carrots and potatoes and onion, celery and parsley roots from the market, chopped into chunky cubes, a chicken carcass from the butcher’s across the road. The smell filled the tiny flat as it used to, every Friday night, when Rafi was a boy.

“Is it over?” she said. The answer, unspoken, was in his eyes.

“How much do you owe?”

“Does it matter?”

“This can’t go on, Raphael.”

“What do you want me to do?” he said. He sounded indifferent to her. “I need it.” He looked around for his cigarettes.

Deborah said, “I threw them away.”

“Ima!”

“How much do you owe?”

There was something new in her voice. Something colder and harder than he was used to. “Twenty thousand,” he said, softly.

Twenty thousand shekels. How could you owe so much money—how could you have so much money to lose? She imagined stacks of fifty-shekel notes, with the writer S.Y. Agnon staring up from each one, the only Israeli writer to ever be given a Nobel Prize by those Swedes far away, in their cold land, stacks of them fitting into a briefcase, how much did twenty thousand shekels weigh? “What are you going to do?” she said.

Her son looked up at her. “I want a cigarette,” he said, sullen.

That night she sat on her bed and listened to his breathing in the living room next door. You could make all the chicken soup in the world, she thought, but you couldn’t fix a soup bowl if it broke. Where am I going to get twenty thousand shekels? she thought. How am I going to save him, my little boy who is dying, moment by moment, from that poison.

She knew in the morning he would be gone, and whatever valuables she still had. And a week or a month or a year later they’d find him dead and apologetic against a drain or a municipal rubbish bin or in the dunes. Somewhere, anywhere, but dead all the same.

“Who do you owe this money to?”

“Leave it, Ima.”

He looked embarrassed that she’d ask.

“Who is it, Raphael?”

At last she extracted a name from him. Chamudi, an Arab dealer in Jaffa. A mobile phone number. “Hello?”

“Is this Mr Chamudi?”

The voice on the line sounded amused. “Who is this?”

“I am Raphael Ben-Zion’s mother. I want to talk–” her voice shook, then straightened. “I believe he owes you money.”

“Rafi?” a laugh on the line. “Rafi’s mother? Mrs Ben-Zion, I don’t know what you hope to achieve with this, if I were you I’d let your son speak for his own actions.” He spoke Hebrew without an accent, he sounded as Israeli as she did.

“He is my son,” she said, simply.

There was a short silence as he considered. “What do you have in mind?” he said, at last.

“Can we meet?”

“Do you have the money?”

Silence on her end; speaking her answer loudly enough.

“Then I don’t think—”

“Please.”

That simple word; or maybe he was just curious.

After she hung up she gathered her things and left the apartment. Raphael was still sleeping. She took the bus to Jaffa. Along Jerusalem Avenue the new Scientology headquarters and cafés where men sat smoking sheesha pipes. Greengrocers’ produce lolling on tables spilling on to the pavement. She went behind a rundown block of flats and no one paid her any attention. Into a dark hallway and up a flight of steps to the first floor and the first flat and she knocked.

“Come in.”

He was alone in the flat. She thought it must be his mother’s flat. It had carpets on the floor, framed photographs on the walls. Chamudi sat in an armchair away from the window, facing the entrance to the living room. He didn’t get up. He was young, a few years older than her son maybe. He wore a red T-shirt and had bony, hairy arms. His hair was cut short all over with a standard number two machine cut. He didn’t smile.

“Tfadal, Um Rafi,” he said, in Arabic. Come in, mother of Rafi.

“I think you speak very good Hebrew,” she said, and he shrugged.

“This is my home,” he said. “This is what I will speak.”

“I didn’t mean anything by it,” she said.

“What can you offer me?” Chamudi said, in his good Hebrew. He looked at her curiously. “Are you sure you want to replace your son’s debt for yours.”

It wasn’t exactly a question. She said, “He is my son.”

“He’s a junkie,” Chamudi said. He said it very matter of fact.

“But he’s still my son.”

“Do you have my twenty thousand shekels.”

Again it wasn’t entirely a question. She shook her head, slightly.

“Then what do you want, Um Rafi?”

“Here,” she said. She took the money out and pushed it at him. It was two thousand and six hundred shekels. It was all she had. “I could pay you the rest when—”

Chamudi didn’t rise. He tsked his teeth. “It’s no use,” he said. “Your boy will just owe more, then. And more.”

“Then don’t sell him no more.”

He sighed. “I have to eat,” he said.

The money was still in her hand. She held it like it could offer salvation. There was no one else in the flat. “Please,” she said.

“I’m sorry. I really am.”

She took off her wedding ring. “Will you take this?” she said. He looked curious again. He reached for the ring and took it and examined it in the light. Then he laughed.

“This is worth shit,” he said.

It was the only thing she had left that Soli had ever given her. He’d bought it honestly. He’d bought it from a jeweller not far from where they were now. Chamudi threw it in her face. It hit her and stung and fell to the thick carpet without a sound. “Tell your boy to get me my money,” Chamudi said dispassionately. “Or next time it won’t end in just a beating.”

She bent down and picked up her wedding ring and slipped it back on her finger. Maybe it was the wedding ring or maybe it was the threat to her son. The sunlight rippled in the room and it was very quiet but for the sound of children in the distance outside playing hide and seek. She took out the gun. At that Chamudi moved very quickly and he was reaching under the armchair when she shot him. She shot him in the chest, once, then stood back and watched him. He opened and closed his mouth several times. There was a hole in his chest and blood poured out over his red T-shirt. He looked surprised.

“This isn’t—” he said and her finger tightened on the trigger again and she put one, two bullets in him, one in the chest again and one in the head. She didn’t know what he had been going to say. She realised she didn’t care.

She held Soli’s old gun and turned it over in her hands. She’d not used a gun since her army service and that was more than twenty years ago. She looked at Chamudi but Chamudi was dead. She noted the fact but didn’t feel anything about it. She put the gun away in her bag and left the room and left the flat and closed the door behind her. An old homeless man by the municipal rubbish bins was squatting awkwardly on the ground, his dirty white underpants around his ankles. He was holding a roll of toilet paper in his right hand. He didn’t pay her any attention.

She caught the bus back. When she got home Rafi, and the last of her jewellery, were gone.

3.

A week later she was crossing the road back home with her shopping when a man stopped her. He was about her age or a few years older, with grey short-cropped hair. He was a large man with a paunch. Let me help you with those bags,” he said.

“Thank you, but I’m fine,” she said. By then she was across the road and at the door to the block of flats. The man said, “I insist.” She looked behind him and saw a black four-wheel drive coming to a halt at the curb. She couldn’t see through the windows. The man said, “You could invite me up for a chat, or we can go in the car, Mrs Ben-Zion. It’s your choice.”

She didn’t say anything, she just waited him out. He smiled. Despite everything he had a nice smile. “What will it be?”

She let him take the shopping bags and opened the door. He followed her inside and up the stairs, uncomplaining. She unlocked the door to her flat and they went in.

The man put the shopping bags on the table in the kitchen and stood and surveyed her little flat. “It’s very nice,” he said, conversationally. “Keep your hands where I can see them, please.”

“Who are you?” She’d had the drawer with her kitchen knives casually open. She closed it.

“Do you follow the news, much, Mrs Ben Zion?”

Deborah shrugged. “It’s not like you can avoid them,” she said. Every day there was something, a terrorist attack or tension on the border or problems with the African immigrants or with the Bedouins or with the Settlements; anyway something.

“Read the papers?”

“Sometimes. Not often.”

“Last week there was a news item—a small news item, admittedly—about a man found dead in Jaffa.”

“I don’t think I saw it.” She was very tense. His face looked familiar, though she had never met him before. Now that she was in her own place she noticed more things about him. He wore expensive but understated cologne and an expensive and ostentatious gold watch on his left wrist. There was thick black hair on his arms. She wondered how he’d found her. Later, she figured it must have been the homeless man by the bins.

“His name was Chamudi. He wasn’t anyone’s favourite person. But he was working for someone.”

“Who was he working for?”

“Me.”

Sunlight slanted in through the window. Deborah took a deep breath. “So?” she said.

“So I was wondering why anyone would wish Chamudi dead. What did he ever do to anyone. Beyond being a piece of shit nobody loved, not even his mother.”

“I’m sure she did,” Deborah said, softly.

He looked at her keenly. “You have a son, don’t you, Mrs Ben-Zion?”

“Yes.”

The silence bore its own implications. “Who are you?” Deborah said, again.

“My name is Binyamin Pardes. Benny.”

The name jolted her memory. The man’s face, surrounded by men, coming out of the doors of the courthouse on Weizmann Street, a beaming smile. The television cameras had followed him avidly, hungrily. A lawyer, young and bland: “My client has always maintained his innocence against these spurious allegations—”

“Oh.” She began to move around the kitchen; to put away the shopping.

He stood there watching her. He had the ability to stand very still. “You’re an interesting woman, Mrs Ben-Zion.”

“Deborah,” she said, putting a bag of sugar on the top shelf above the sink.

“Here,” Benny said. “Let me help you.” He took the bag from her hand. For a moment his fingers touched hers. She could smell his cologne.

“Thank you.”

He moved away. “Your son owed twenty thousand,” he said.

Deborah unpacked celery and potatoes. “Owed?”

“I’m willing to cancel the debt,” he said. “But of course, you still owe me for a life.” She looked at him directly, then. He had brown eyes as cold as Jerusalem in December. “I have to ask you a question,” he said. “What did you feel when you put three bullets in Chamudi?”

She had to think about it, for a moment. Then she said, “Nothing. Isn’t that strange? I didn’t feel anything at all.”

4.

She didn’t know why she didn’t go home after the Aharoni shooting. She took the bus and the murder was already on the news, reporters had descended on the mall in north Tel Aviv and were broadcasting excitedly of another gangland assassination in the escalating fight between the families. There were so many crime families it was hard to keep track of them, co-existing in a complex network of rivalries and co-operation that shifted and changed with old grievances and new alliances.

She got off by Charles Clore Park, the southern beach where once the Arab village of Menashiya stood. She walked along the promenade and smelled the sea. A young Orthodox couple sat chastely on the rocks. Kids on skateboards rolled past, sharing a joint. Black-clad Muslim women walked past pushing prams, chatting. Deborah followed the pathway. Salt spray flew in the air from the waves pushing against the rock wall. She thought of Aharoni’s face, his surprised eyes, that condescending tone when he called her buba, doll. All that time back when Benny found her, she told him she felt nothing when she pressed the trigger. But that was a lie. There was a heightened sense of perspective, somehow, even an exhilaration, and she knew that he knew, that he felt it too. It was a bond between them.

But still, she couldn’t help thinking about it now. There was something so vulnerable in men’s eyes the moment before you shot them. A dumb surprise that it was a woman. And disbelief, till the very moment, that it was happening at all. No one ever thought they were going to die. She followed the trail to Jaffa and walked away from the sea, along Salameh, where tiny factories and junk and scrap metal yards flourished like industrial flowers. Motti’s was just around the corner, it was one of Benny’s places and they had a working furnace where she sometimes disposed of the guns, but she didn’t do it now.

Something had changed and she didn’t know what.

She took out her phone and called her son. “Raphael? It’s me.”

“Ima!” he sounded happy to hear her. His voice pinched her heart. “Are you coming for Friday dinner?”

“I don’t think so, sweetheart,” she said. She took a deep breath. “In fact, I was thinking—why don’t you and Galit go on holiday?”

“Holiday? What, in the middle of—I mean we don’t even have the m—what?”

“I have some money put aside. Wouldn’t it be nice if you and Galit went away, for a while? Italy maybe. It’s so pretty this time of year.”

She had gone two years before, to Rome and then Naples, with Benny.

“That’s crazy,” Rafi said. “I can’t just leave work and—”

“Please, just think about it. I’ll come by.”

She hung up abruptly. She decided to do it now, before she could regret it. But it still took some time. She took another bus to the bank and took out the money, all the money that she’d saved away in a safe deposit box all those years. Then, feeling suddenly flush, she took a cab. On the radio they talked about the shooting and she asked the driver to switch it to another channel, the army’s one, that played music and didn’t have commercial breaks.

“You look happy,” the cab driver said, apropos of nothing.

“Do I?” Deborah said. She looked at her reflection in the window. Was she happy? She saw the crow’s feet at the corners of her eyes. The loose skin of her neck. She realised she had been humming without knowing it, an old song, Arik Einstein’s “Avshalom”, with the refrain, “Why not, Why not now?”

She’d never thought of it before. She said, “I suppose. I suppose so.”

“That’s nice,” the driver said.

“Yes,” Deborah said. “That’s nice.”

She sat back against the seat and looked at her reflection in the window again, and she was smiling.

5.

It must have been a month or two after Binyamin Pardes first came to see her that the job came up. She’d not seen him since the first time he came. For some time she did not hear from her son and she was sick with worry. Then Rafi called her, and he was in a rehab clinic, he had been checked in by people—he was vague on the details, but he assured her everything was fine.

So when Benny finally came again to see her she wasn’t surprised. Again, he was alone. This time, he was waiting in her flat as she came in. He was sitting in the armchair by the window where Soli had liked to sit, and he was smoking a Noblesse cigarette, the cheapest, local brand. He looked up when she came in with her shopping and his eyes crinkled with amusement.

“Mr Pardes,” she said, awkwardly.

“Benny, remember?” he said. He got up and helped her put away the shopping, courteously, and then he stood by the window and finished his cigarette. “Rafi is ok?” he said.

“Yes,” she said.

“Good, good,” he said. “He’s a good kid.”

“Yes.”

“Listen, Mrs Ben-Zion—”

“Deborah,” she said, and he laughed.

“Deborah,” he said. “How would you like to do me a favour?”

“What sort of favour?” she said.

“Have dinner with me.”

“What?”

He laughed again. He had an easy laugh.

“Nothing fancy,” he said. “I know a good fish place. What do you say?”

She said yes. Later, they went downstairs. His car was parked a block away, on a side street. The car wasn’t fancy, it was one of those Japanese cars. He opened the door for her.

They drove along the sea to Bat Yam and to a little fish restaurant overlooking the sea. The food was good. Deborah found herself laughing when he told jokes, when he told her stories about famous people he knew from his night clubs, or funny incidents from his military service. He was easy to talk to. He wasn’t at all what she’d expected.

The restaurant was near-empty. It was early. As they were drinking coffee he reached for her hand under the table. His hand was dry and warm. He took her fingers in his and put them against the underside of the table and she felt something cold and hard attached to it. She didn’t flinch. Benny nodded.

“A man is going to come in here in about five minutes,” he said. “A short, fat man wearing a brown-coloured toupee. He has a mole on his left cheek. He runs all the drugs this side of town and I need him out of the way.”

She didn’t say anything. He said, “Are you listening?”

“Yes.”

“Good. I’ll wait in the car, around the corner. Don’t run. Do it quietly. He’ll have his boys with him but they don’t know you.” His fingers left hers and he got up, quickly. She saw him look at the proprietor and nod and the proprietor nodded back, nervously, and looked away. Then Benny was gone. She sat there over the remains of her coffee with her hand under the table, touching the gun metal, tracing the velcro straps that held it to the underside. Five minutes later, with a final piece of baklawah swimming in honey and rose-water before her, a man came into the restaurant with two younger men behind him, who looked at her momentarily with cold hard eyes and lost interest. They swept into the room and sat by the windows, far from the door. She waited, watching them. The older man had a mole on his cheek. Salads and dips and warm pita bread arrived as soon as they sat down. She sat there for a while not thinking of anything much in particular before reaching under the table and pulling the gun free. It felt so heavy. She checked it blindly, under the table, and put it into her handbag. She got up at last and pushed the chair in and went to the toilets and waited. Presently he came, as she knew he would, puffing a little as though he found even the simple exercise tiring. He stopped when he saw her in the shadows, then smiled without warmth and said, “Are you lost, lady?”

“I think so,” she said. She took out the gun and pressed it against his chest and shot him, at close range, and he didn’t even react until he fell back from the impact. She shot him again at close range in the head—what in the army they used to call a confirmation kill. She didn’t know how loud it was. She didn’t run but she walked away and outside and she saw the two younger men still sitting by the windows—they didn’t even glance her way.

6.

It made her smile even now. Men were always most vulnerable on the way to the toilet. They paid no attention, they were in a hurry, being shot came as almost a relief. They’d never need to pee again. In a way, she was doing them a favour.

“Here is fine,” she told the driver. He stopped the cab and she paid the fare. She walked the rest of the way to Raphael’s house. He was living with Galit now, she was a nice girl. It wasn’t the best neighbourhood but it wasn’t the worst, either, and she could smell the sea in the distance, you were never far from the sea in Tel Aviv.

She rang the bell and Rafi answered almost immediately. She gave him a hug and pulled back and looked at him, holding his head between her hands. He was taller than her. He had Soli’s eyes.

“What’s going on, Ima?” he said, puzzled. She followed him in. Galit was there, in the kitchen making coffee, and she gave her a hug and a kiss, too. “I won’t stay long,” she promised.

“Ima, what’s going on?” Rafi said again. Deborah said, “I just thought it might be nice if you …” she hesitated. She didn’t know how to put it, exactly. She could still change her mind, she knew. But she also knew she wouldn’t. “I think it might be best if you went on holiday,” she said. “Just for a little while.”

“Why, are we in trouble?” Rafi laughed. The idea was absurd. His bad times were behind him. At least, she hoped so.

“No, I just … I have some money put aside, and you two haven’t had a holiday and, well, I thought you might like to see Italy.”

“Well, I suppose,” Rafi said. “But—”

He and Galit exchanged a look, the way couples did. It made Deborah feel at a loss. She and Soli never spoke much between them. A look was all he needed from her to know what to do.

“Coffee, Deborah?” Galit said.

“Yes, thank you.”

They drank it still in the kitchen, all standing up. No one said much. It was obvious they were concerned about her. Finally she took out the envelope she’d prepared earlier, when she’d left the bank. “Here,” she said. “It’s all there. I want you to call me when you get to Naples.”

“Naples? Ima, are you crazy? Who is going to Naples? Where is Naples?”

“I’ve never been out of the country,” Galit said, dreamily.

“We can’t just—what’s in the envelope—” He tore it open and looked inside and then, in horror, “Where did you get this, Ima?”

“I told you, I saved it up.”

“It’s too much!”

“I would give you everything, Raphael. You know that.”

She turned, quickly, so they wouldn’t see her cry. She walked to the door. They followed her, bewildered. “Are we in some kind of trouble?” Rafi said again. She hugged him, holding him tight.

“Nothing I can’t handle,” she whispered. She hoped she was right. She couldn’t tell him they weren’t in trouble, yet. But that they will be.

Outside it was hot and humid but she walked, she didn’t mind walking today. It gave her time to think. All she knew was that she was tired doing men’s work. She also knew there was only one way out, and that way was death.

It would have to be done right.

7.

Deborah Ben-Zion and Binyamin Pardes became lovers the night she killed the man in the fish restaurant. Later, on the news, she found out his name was Modechai Saakashvili; that he was born to Jewish-Georgian parents in Bat-Yam; that he was married and a father of two; and that the Tel Aviv YAMAR, or central detective unit, suspected him not only of involvement with drugs and prostitution but also to have had a direct hand in several executions carried out in the past several years, to which no witness had ever come forward.

That evening, however, she simply walked out of the restaurant and found Benny in his car and got into the passenger seat and they drove to Jaffa, to a scrap yard. She waited in the car as Benny went in there with the gun wrapped in cloth and then he came back without the gun.

“Did you destroy it?” she said.

He didn’t answer. She thought that he may have kept it, to always hold it over her. It was what they did in the movies, didn’t they? But she couldn’t get worked up about it if he did. It seemed to her not to matter, much, anyway.

They drove away. The radio was on, playing Arab music. A weight of unspoken words lay between them in the stillness of the car. A fat moon rose above the dark sea.

“Stop the car,” she said, minutes or hours later. He pulled over to a lay-by. Black waves crashed against the shore. She fumbled with the seatbelt. Why did she need a seatbelt? What did a seatbelt protect you from? It didn’t stop bullets. She found that she was laughing. It was all so funny. Benny reached over and calmly helped her with the belt. She reached and took hold of his hands. She looked into his face, his eyes. She wanted to hit him. She knelt into him and kissed him on the lips. His lips were warm. He was warm all over. His big hands ran over her body. She pressed into him, urgently, he smelled of aftershave and sweat, his skin tasted of salt. They were tangled up, as hopeless as teenagers. Somehow they pushed the seats back. She fumbled with his belt. His fingers, impatient now, all but tore the buttons off her shirt. His mouth devoured her skin, her hands ran through his short, cropped hair.