Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc.

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

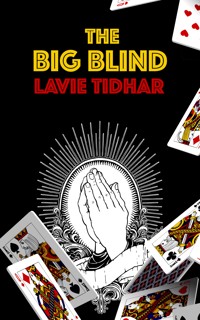

"Tidhar changes genres with every outing, but his astounding talents guarantee something new and compelling no matter the story he tells." –Library Journal The daughter of a legendary card player with skills of her own, Claire doesn't want to go into the family business. She's heard the call, and she desperately wants to become a nun. But when her convent comes under financial threat, Claire must leave what she loves to save what she loves–and enter an international poker tournament. Both a poker novella and a meditation on faith, The Big Blind is a taut, heartfelt and compelling new book from multiple award winner Lavie Tidhar. "Lavie Tidhar is one of the great writers of my generation." –Silvia Moreno-Garcia, author of Mexican Gothic "An utterly original voice in contemporary fiction." –Daniel Polansky, author of The Seventh Perfection "In a genre entirely of his own, and quite possibly a warped genius." –Ian McDonald, author of Time Was

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 113

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE BIG BLIND

Copyright © 2021 by Lavie TidharAll rights reserved.

Published as an ebook in 2021 by Jabberwocky Literary Agency, Inc., in association with the Zeno Agency LTD.

Cover design © 2021 Silvia Moreno-Garcia.

ISBN 978-1-625675-41-5

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places and events are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Title Page

Copyright

The Big Blind

About the Author

Other Books by Lavie Tidhar

THE BIG BLIND

1

Claire said, ‘Raise.’

She stacked chips. One pile, two, three. Started again. Not looking at the cards, not quite looking at the other players. Not not looking, either.

It was quiet in the small poker room at the back of the Dales. The sound of chips, the snap of cards on the felt. Cigarette smoke in the air, and someone coughed, someone else said, ‘One time, just one time,’ softly at another table.

Claire pushed the chips in, with a sort of careless studied gesture. They toppled across into the pot. It was a large pot.

The player on her left said, ‘All in,’ and pushed the remainder of his chips in. Immediately. But she’d expected him to do that. He had a short stack.

The rest folded, one after the other, until it came to the Docker. He was a short man and now running to fat but there was muscle under there. They said he used to work the docks. They said he did time in an English prison. They said all kinds of things. He looked at her. She looked nowhere, trying not to give anything away.

You never played the cards, as the old saying went, you played the players.

He took his time, but that was all right. He had a big decision to make.

She wished he’d get it over with, though.

‘A flush?’

Someone else said, ‘Only one way to find out.’ Someone else laughed, but quietly. The Docker shrugged and folded.

She turned over her cards and the short stack did likewise. The river was a three of hearts and she didn’t make the flush but her two pair still beat the short stack’s. He got up to leave the table.

‘Nice hand.’

She shrugged. The dealer shuffled the cards and dealt and round the table they went again.

* * *

There were three of them left after another hour. Her and the Docker and some kid, kind of cocky, with black curls of hair. He flashed her a grin. Nice teeth, and he knew it. He bet. She called, wanting to see the turn.

When the turn came it didn’t come her way but she had position and she used it, applying pressure, and the kid folded.

‘Hey,’ he said, ‘what’s your name?’

‘Claire.’

‘I’m Mikey.’

‘All right.’

He smiled again. He had an easy smile.

‘You’re good,’ he said.

‘I know.’

Even the Docker smiled at that. The next round he raised pre-flop, she folded, and the kid called. She took a sip of mineral water, watching the play. A raise and a call on the flop. She couldn’t read either of them.

On the turn the kid went all in. Quick call from the Docker. He turned his cards over. A full house. A look of disgust in the kid’s eyes. Turned his own over. It was a lower full house.

River came. It was a deuce of spades, no good to anyone. The kid got up.

‘Good hand.’

‘Yeah,’ the Docker said.

‘Mikey.’ The kid was looking her way again. Wore a new smile, like he had no care in the world. She thought maybe he didn’t.

‘Excuse me?’

‘Just in case you forgot. I’ll be seeing you?’

‘Why not, long as your money’s good at the table.’

The kid laughed. Then he went over to the bar and got himself a beer.

* * *

A few rounds later the Docker went all in on a semi-bluff and she called with a three of a kind but he got lucky on the river and with that the game was over. She collected her second-place winnings from Peg, the cashier.

‘How’s your dad, Claire? He’s not been round these parts for a while.’

‘He passed. Last year.’

‘I didn’t know. I’m sorry. Was it… ?’

‘It was cancer. It was… It was pretty quick.’

Peg touched her hand, lightly. ‘I’m sorry.’

‘Thank you.’

‘He was a character, was your dad.’

‘Yeah.’ She tried to smile. ‘He was.’

She took the money and turned to leave. Went past the kid, Mikey, necking a bottle of beer. Gave him a nod as she stepped out into the night, cold air, the smell of rain.

She pulled her coat around her and stepped into the drizzle.

* * *

She had to wait at the bus station for over an hour. She got a coffee and when she’d finished it she went into the bathrooms and changed into her habit.

* * *

The ride back was quiet. Her head rested against the window. It was another hour on the bus and dawn was just beginning to break on the horizon when they got to her stop. She got off.

There was no one around and the convent was quiet. She climbed over the wall and got in and went into the chapel and put the envelope with the money into the collection box and then she went up to her room. She lay on the bed, staring up at the ceiling, and fell asleep for an hour before waking up again for Vigils.

2

‘Raise, five hundred,’ Sister Bertha said. She pushed three red-topped matches and four burnt matches across the table into the pot. It was after Compline and the three of them were playing cards on the low table in Sister Bertha’s room.

Sister Mary looked at her, frowned, and folded.

‘Re-raise,’ Claire said. ‘Two thousand.’ She pushed across twenty matches, none of them burnt. Each was worth one hundred. Sister Bertha glared at her.

‘You’re bluffing.’

‘Only one way to find out.’

‘You think you can push me around, Claire?’

Claire shrugged. Sister Bertha drummed her fingers on the tabletop.

‘You’re bluffing,’ she said again.

Claire kept her face impassive. It didn’t do to underestimate Sister Bertha. Her play was aggressive and she was fearless. If she had anything, she’d call without qualms.

The question was: Did she have anything.

‘Why the big raise? Are you trying to push me off the pot?’

Nothing.

‘You have queens?’

Bertha had an uncanny ability to read the table.

‘Cowboys?’

Claire said nothing.

‘What do you have that could beat me?’

The longer they talked, the more likely they were to fold. Bertha was just trying to talk herself out of calling.

‘Oh, heck,’ Bertha said, and folded, at last. Claire turned over one card, and it was the Queen of Spades. She mucked the other one and smiled at the older woman.

‘Oh, heck,’ Bertha said. She took the cards and began to shuffle.

‘Mary, you’re the small blind,’ she said.

‘I’m almost out of matches,’ Sister Mary said.

‘Chips.’

‘I mean, chips.’

She had a quiet way of talking. She posted the small blind, two black matches. She only one had red match left.

‘Well, you’re still in the game,’ Sister Bertha said. ‘All you ever need is a chip and a chair.’

‘Where did you learn to play?’ Sister Mary asked.

‘Back room of my daddy’s pub.’

‘You play so well.’

‘Not as well as her,’ Sister Bertha said, and pointed her thumb at Claire. ‘I can play for matches. She can play for God.’

‘Do you think it’s wrong?’ Claire said. She said it quietly. Sister Bertha was laying down cards.

‘What?’

‘Do you think it’s wrong? To gamble?’

‘Gambling is not a sin, child. Avarice is. Do you play for the love of money, Claire?’

‘No. But I…’

‘You’d play if there was no money involved. You’d play for matches. You play because God’s given you a talent, and you use it.’ Sister Bertha smiled as she watched Sister Mary pick up her cards. ‘And besides, if poker really was just a game of luck, even Mary here might win a hand every now and then. Raise, one thousand.’

‘I fold,’ Sister Mary said meekly.

3

Claire chopped onions. She added them to the big pot. The onions sizzled as they hit the hot oil. Made her think about her father, coming back from a late-night session, walking in. He’d smelled of sweat and cigarettes and aftershave. He always dressed well for the games. Didn’t matter where the game was. A rich man’s home or a caravan park, the back room of a pub or the Legion. He always dressed the part and he often carried a gun. Back then, poker was illegal, and more than once he’d had to defend his winnings. When he’d come home he’d take off his jacket and roll up his sleeves and go into the small kitchen and cook. The smell would often wake her up. Fried onions, sausages. He’d sit at the kitchen table and eat his meal and she’d come in and get a hug, and sometimes they played a hand or two while he ate. Her father was never far from a pack of cards.

‘What am I supposed to do with these cuts?’ Sister Mary said.

The man from the chicken factory shrugged. ‘Beggars can’t be choosers, Sister,’ he said.

Sister Mary held up a hairless wing dangling between her fingers. Even from where she was standing, Claire could see the sheen of perspiration on the skin of the chicken.

‘Well?’

‘It’s not expired,’ the man said. He was more defensive, now. ‘It’s fine to cook.’

‘And anyway it’s nothing but skin and bones.’

‘Look, sister, what do you think I can do, here?’

‘Show compassion for the needy.’

The man shrugged, defeated. It was hard to argue with a nun. ‘It’s not up to me,’ he said tiredly.

When he was gone Claire helped Mary move the boxes. The smell of the chicken cuts wasn’t particularly pleasant. She and Mary did their best cleaning up the pieces – wings, necks, giblets. Claire added the wings into the pot and stirred them round. The necks they could use for soup. She added stock and potatoes and carrots that had come in from a donation the day before. They were lumpy, and had taken forever to clean and peel, but they would do.

It was warm in the little kitchen. Beyond the counter the regulars were already assembling. The television was on with the sound down low and a daytime talk show where people shouted at each other. Claire left the pot to boil and helped make tea. People always wanted tea. The town had been prosperous once, long ago, but with the mines all closed and only the chicken factory on the edge of town running, it was hard to make ends meet.

‘I don’t know what to do,’ Sister Mary said.

‘It can’t be that bad,’ Claire said.

‘It is,’ Sister Mary said; but she said it quietly.

* * *

They served lunch and everyone was very orderly and Marybeth Ryan came in with her new baby and everybody gathered round to coo at him. It was a little boy. When everyone’d finished and left home for the day, Claire and Mary cleaned up and Claire looked at all the tiny bones that were left on the plates.

It was hard work but it was satisfying, and she knew they helped people. When they finished they walked back to the convent, which lay on the outskirts of the town. She looked at the old building and she knew how rundown it was, and how the roof needed repairing, and how cold it got in the winter with drafts coming in and mould growing in the corners from the humidity. After Compline she went back to her room and lay down. She read a little from her book – Doyle Brunson’s Super System, an old favourite – but then she put it down and she fell asleep almost immediately.

4

‘I was playing this kid last night over at the Victoria, I raised with nothing, deuce eight off-suit, kid called, I got trip eights on the flop. Kid raised me, I raised him all-in, he called. Next thing you know I’m busted out when he made his flush. Just my luck, right?’

He looked at Claire as though expecting a reply.

‘So?’ she said.

‘So it wasn’t any fun.’

He raised and she called.

‘I didn’t see you there,’ he said.

‘So?’

He gave her a grin. ‘So if I did, it might have been more fun.’

Another night, another game. She paired her jack on the turn. Mikey was slow-playing his cards. Claire paired her queen on the river. She pushed a big bet. Mikey looked at her ruefully and folded.

‘Maybe not that much fun,’ he said, and she laughed.

She played tight for the next few hands. Mostly sitting them out. The cards weren’t going her way and she didn’t feel like mixing it up. This wasn’t an elimination tournament, it was a cash game. Patience paid.

‘Are you going to London?’ Mikey said.

She looked his way at the apparent non sequitur. ‘Excuse me?’

‘London,’ he said, drawing out the name.

‘What’s in London?’ she said.

‘The EPC,’ he said. ‘The European Poker Championship.’

‘Oh,’ Claire said. ‘No, I don’t think I am.’

‘Why not?’

‘Excuse me?’

‘I said, why not? You’re good.’

‘I don’t—’ she almost checked her cards then, even though she’d just folded. She gave him back a look, the sort that said Are you for real?

‘What’s your deal, Claire? I can’t figure you out.’

‘Are you going?’ she said.

‘It’s a five grand buy-in,’ he said.