Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc.

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

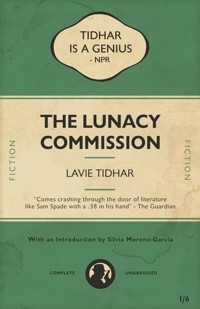

"A complex, layered and hugely enjoyable story" –Bestsf "Lovely work" –Locus When a mysterious message arrives from vanished New Atlantis, a restless Mai undertakes the perilous journey to its drowned isles. But the journey is long and hard: through the Blasted Plains and the ancient cities of Tyr and Suf, through shipwreck and wilderness. For this is a world where ants develop inexplicable weapons, where a lonely robot lives surrounded by cats in the ruins of old Paris, and where floating coral islands host sleeping sentience. Mai's journey takes her by land, sea and air to the islands of New Atlantis, and to the nightmare prison buried underneath old London. On her way she will find heartbreak and love – and a new life, awakening. PRAISE FOR NEW ATLANTIS "Excellent... not a word is wasted" –Sfcrowsnest "Amazing" –1000yearplan "A wonderful, imaginative story" –SFRevu PRAISE FOR LAVIE TIDHAR Winner – The World Fantasy Award Winner – The John W. Campbell Award Winner – The British Fantasy Award Winner – The Jerwood Fiction Uncovered Prize Winner – The Neukom Literary Arts Award Winner – The Kitschies Award Winner – The BSFA Award "Tidhar is a genius at conjuring realities that are just two steps to the left of our own." –NPR "Tidhar changes genres with every outing, but his astounding talents guarantee something new and compelling no matter the story he tells." –Library Journal "In a genre entirely of his own, and quite possibly a warped genius." –Ian McDonald, author of River of Gods "One of the foremost science fiction authors of our generation." –Silvia Moreno-Garcia, author of Gods of Jade and Shadow "Already staked a claim as the genre's most interesting, most bold, and most accomplished writer." –Locus "One of science fiction's great voices." –Starburst

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 122

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

New Atlantis

Copyright © 2019 by Lavie TidharAll rights reserved.

Published as an ebook in 2020 by Jabberwocky Literary Agency, Inc., in association with the Zeno Agency LTD.

Originally published in 2019 in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction

Cover design © 2020 Sarah Anne Langton.

ISBN 978-1-625674-96-8

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places and events are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Title Page

Copyright

Prologue

I. The Message

II. The Roads Must Roll

III. The Sun Harvest

IV. The Tomb

V. The Ceremony Of Innocence

VI. Shipwrecked

VII. La Ville Lumière

VIII. Breach

IX. The Drowned World

Epilogue

About the Author

Other Books by Lavie Tidhar

Prologue

Listen.

Outside, the skies darken. The male nightjars’ voices rise and fall in their churring songs, and they blend harmoniously with the chirps of the field crickets. My daughter’s children and their friends run laughing on the paths. I long to join them.

It is Chuseok, the festival of the harvest moon. I can smell jasmine, lilac, and the deep, rich scent of the small pink flowers of the Arbre de Judée tree which grows outside my window, and which I planted there as a little girl with my mother, long ago.

My name is Mai. I have lived on this Land for eighty-four years and I love it, deeply. I was born here, and it was here that I learned to write: which is to say, to attempt to give shape to the world. And so it is here that I write this, the chronicle of a life spent under the broken moon, of a life spent on this Land, from which we all come and to which we all return, but for those few of us who once tried to go to the stars.

I wish to go outside, to join my daughter and my granddaughter and my grandson, to watch the paper lanterns as they light up the night sky. The moon is broken, but it is still the moon. The Earth was broken, and billions died, but we endured, the way weeds do.

This festival, like all our celebrations, is a mélange. When the earth shook and the seas rose and the sky was rent and the moon broke, the survivors of our species came from all corners, by paths both perilous and desperate to this place. I could give you the old names of things, but I can tell you where it is by what it grows: pines and weeping boletes, wild thyme and wood sorrels, dandelions, jasmine…

I wish to go and join them, but the days grow short and the nights long, and I write this in the light of a lantern adapted from an old mortar shell, the sides cut out and fitted with old glass that was itself salvaged. My mother was a salvager, journeying each autumn, after the harvest moon, along the old roads where the vehicles of the ancients rusted in their millions, and on to the ancient ruined cities, where only salvage and junk and a few old machines, still alive, remained. Each year, I would hold my father’s hand and watch her go. The salvagers departed for months at a time and returned in spring, bringing back with them all that was still usable. I longed to go with her, and to see the ocean, and to smell the salt in the air and see not just Land, but Sea. And one year I did that, too, and one year she disappeared, and I searched for her… But that is another story, for another time. I never became a salvager, it was not in me; but I did become, in lieu, a chronicler of sorts.

But I digress. My daughter calls me to come out. I do not want to miss the lanterns. Later, we’ll eat baked flatbread, olives, winter kimchee, watermelons. We’ll drink young, red wine. The flowers bloom. My father told me, Never pick a flower. Let them grow where they are. We keep the plants, and, in our clumsy way, we try not to trespass upon the planet.

So hush. This happened long ago, in my third decade on the Land.

A message came, one day, from the place we now call the New Atlantis, where the seven sacred islands lie…

I reluctantly went on a long, hard journey. I encountered loss, and I found love. I saw the sun harvest in Suf and the fabled floating Isles of the Nesoi, and I suffered shipwreck. I met the mad robot, Bill, and I saw the ruins of La Ville Lumière. I visited Atlantis.

Then I came back.

That is the story.

Everything else, as the old poet once said, is just details.

I. The Message

It had been a cold and shivery winter and I had been restless through much of it. The fog lay heavy on the Land in nighttime, and the yellow light of the broken moon struggled to illuminate the landscape through it. I took long midnight walks through the silent Land, observing spun spider webs glittering with tiny drops of dew like hardened diamonds, and snails that communicated silently with each other in the mulch of leaves, their retractable tentacles raised in complex greeting.

Ants whispered softly through the forest, marching across fallen pine needles, over the raised roots of ancient trees. In the stream that ran beyond our homes, the eels slithered through the water on their way back to the distant sea. All was quiet, but for the faraway call of a migrating cormorant. The birds traveled to our shelter in winter, but left again in the spring, to go north and west. I was restless, desirous of something I could not put a word to. An irritability I was unable to shake off drove me through much of that winter, and my father took to finding shelter in his library, where he pored over ancient manuscripts my mother had salvaged for him in the ancient cities of the coast. Turning the pages of an illustrated atlas of the old world, he’d glare at me over the glasses perched on the bridge of his nose. “What you need,” he’d say, “is a purpose, Mai. And stop stomping quite so much! I can barely hear myself think.”

“But I don’t!” I’d say, and stomp my feet, the way I had when I was little, and he’d soften at my frustration and smile his old smile and say, “Would you like me to tell you a story?”

My mother, the salvager, ever practical, had a use for maps only if they were current. Salvager maps were makeshift, continuous works-in-progress. They marked known nests of wild machines, where a river had shifted, where a new road had been hewn, where there was danger, where there was salvage. My father, by contrast, dreamed of the world as it had been, not as it was. For hours he would trace winding blue paths on the ancient maps, and speak to me in the language of long-vanished waterways: “Bosporus, Mother Volga’s Watershed, Pearl River, the Lower Blue Nile…”

My mother salvaged scrap and debris, anything from the old world that could be repurposed. She was a stoic, practical woman. She hated waste. My father, by contrast, was a man given to daydreams and stories. He was endlessly fascinated by those missing decades, by the centuries before them, that glittering time of consumption and excess, when the roads were laid all across the flesh of the Earth and a billion petroleum-fed travel-pods crawled like fat beetles along them. Only their scars were left to us.

I stayed restless all throughout that winter. I tilled the soil in the fields and helped Aislinn Khan, Mowgai’s mother, in the bakery, enjoying the warmth of the oven and the silence of the predawn night that lay as thick as a blanket over the houses and their sleeping inhabitants. I helped Elder Simeon oil the gears of the small mill on the brook, surrounded by his pets: tiny, intricate clockwork automata of ducks and geese, a peacock, a cat, a turtle. From the mill I could look out to the low-lying hills beyond the brook, past Elder Simeon’s house, where as children Mowgai and I would imagine they formed the shape of a vast, reclining manshonyagger, a buried giant forever sleeping, a snatch of nightmare from the old age.

I waited, for what I didn’t know. Perhaps for spring. Mowgai was a salvager now, and he and the others were gone with my mother, to the Blasted Plains, to the ruined cities by the coast.

I read old books, I played backgammon and bao and cap sa with my neighbors, I dug fleshy cyclamen bulbs out of the soil to replant, and drove my father deeper and deeper into his study. I had just come off three years in New Byblos working on the Extinction Lists, and off a relationship I had thought would last, but didn’t.

As the days lengthened and the nights grew short, flocks of storks began to migrate across the brightening skies, black-and-white, black-and-white on the thermal winds.

It was on a day such as this, the air still cold in the shade but the sun warm, and the air filled with the fragrance of spring, that I saw a familiar bird shape circle in the sky overhead. It was a gray spot against the sky, and as it descended, I recognized it as Hornbill, a wild drone Mowgai had rescued from a malfunctioning replicator nest in the Blasted Plains and raised as his own. It was far into its life cycle by this time and spent much of its days nestled unmoving as it absorbed sunlight, but I knew how attached Mowgai was to it.

If it was here, Mowgai and the other salvagers couldn’t be far behind.

Could they?

Hornbill spotted me and gracefully descended. It opened its vicious-looking beak and Mowgai’s familiar voice emerged. The message was brief and addressed to me. It said they were on course for return but were still two or three weeks away. I could hear wind behind them, the crying wail of wild dogs far in the distance, the rattle of shifting pebbles underfoot. Mowgai sounded tense, yet I could imagine him smiling. I smiled on hearing his voice, in the happiness of recognition.

“Mai…” He paused there. I heard my mother’s voice in the background, saying something I couldn’t decipher, and Old Peculiar’s grunt in reply. “There’s been a message for you.”

That pause again, the hiss of wind. Hornbill blinked at me, his mottled gray hide thickening to black as it began to power down. The old machine was tired. I tried to think of who would contact me. For a moment I thought of Ifrim, back in Byblos, and felt a pang of loss.

“From beyond the sea.” I could hear exhaustion in his voice. “Meet at the way station.”

Then the sound faded, and the old drone powered down, trusting me to carry it. I returned to my parents’ house, left Hornbill to nest on the roof, and went inside to hunt for my father in his library.

“Beyond the sea?” my father said, doubtfully. He brewed us tea, fresh sage leaves and just a hint of honey in the water. We watched the rain outside, but it was a final gust of winter, and I could see new shoots on the plants, and the flowering trees. I could smell the coming spring, as though the Land and everything upon it were holding their breath in delighted anticipation. It was the season of rebirth, of joy. “What is there beyond the sea?”

“There are other places than these,” I said. I paced around the room. I hated mystery. Or did I? My father looked at me and shook his head.

“You’ve been like a caged bird all winter,” he said.

“We don’t cage birds,” I said, irritably.

“Then perhaps it is that you, too, should fly,” he said, and smiled, and blew on his tea in the way that had always annoyed me, even as a kid. He took a sip, and kept the smile, and I was forced to smile, too.

“Francia, Albion…” he said musingly. “Or does the message mean Afri? Misr, Carthage…”

“Your geography is as muddled as your history,” I said, laughing. But the truth was that I longed to go—somewhere, anywhere. The restlessness I’d felt all winter had vanished, and in its place came a clear, pure determination.

My father took another sip of his tea and looked up at me with guileless eyes.

“So when do we leave?” he said.

The journey out wasn’t hard. We followed the stream, enjoying the waking Land, the blooming flowers, the new warmth in the air. Bees buzzed lazily about us. It was, though I did not realize it at the time, the last such journey I would take with my father. He was in good health, his steps long and assured, yet unhurried. He seemed determined to enjoy the long hike, and his joy was infectious. For all that he loved old books and their stories of the past, he was a child of the Land and he loved it wholeheartedly. As we walked he told me stories, the way he had when I was but a girl: of huge flying machines that crossed over the oceans; of vast, glittering temples where every manner of thing was put on display and could be had for the asking; of a planet filled with a humanity that was always rushing, hungry, filled with a giddy need and an uncontrollable energy. He’d stop to show me flowers: poppy, wolf’s bane, wild thyme. We skirted anthills, saw shy deer observe us in the distance. In the night, we built a fire and sat around it, and I told him of my time in Tyr, where they sing still of the old days, and of my work in Byblos. I did not speak of Ifrim, and my father did not ask. Some wounds heal slowly.

In this manner we traveled for some days, at last departing the brook for a path left by generations of salvagers. The ground began to rise here, and my father walked more slowly, and at night we saw foxes, jackals, once a wildcat. One day we saw the paw prints of a bear not far from where we’d made camp for the night.

Then we reached a steeper incline, and as we crested it we saw below us the way station.

My father is long gone now, and buried in the Land he loved. His flesh has fed and nourished others, the plants and worms which are our friends and neighbors. The chill of the nights often invades my bones now, and many years have passed, and yet it seems so fleetingly, as though it had only just happened. And I am glad I had that time with him.