Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc.

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

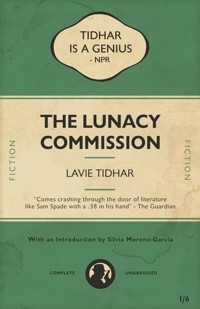

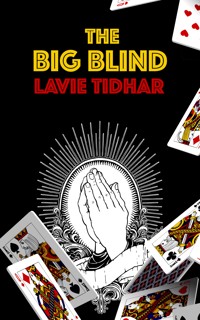

"Tidhar changes genres with every outing, but his astounding talents guarantee something new and compelling no matter the story he tells." – Library Journal A nun enters a poker tournament as she wrestles with her faith in God; a boy travels across a mysterious, cloud-covered planet in search of a mythical space port; in Nazi-occupied London a screenwriter searches for an old flame with deadly consequences; three wise men from the East travel to Judea to give a newborn baby an unexpected power. Collected for the first time in one volume, this omnibus edition from World Fantasy Award winner Lavie Tidhar gathers four mind-bending novellas: The Big Blind, Cloud Permutations, The Vanishing Kind, and Jesus and the Eightfold Path. "Lavie Tidhar is one of the great writers of my generation." – Silvia Moreno-Garcia, author of Mexican Gothic

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 485

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Four Novellas

Collection copyright © 2024 by Lavie Tidhar

Published as an ebook in 2024 by Jabberwocky Literary Agency, Inc., in conjunction with the Zeno Agency LTD

The Big Blind copyright © 2020 by Lavie Tidhar

Cloud Permutations copyright © 2010 by Lavie Tidhar

The Vanishing Kind copyright © 2016 by Lavie Tidhar

Jesus and the Eightfold Path copyright © 2011 by Lavie Tidhar

Cover art: “Kleines Warm” (1928) by Wassily Kandinsky

All rights reserved.

ISBN 978-1-625676-74-0

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc.

49 W. 45th Street, Suite #5N

New York, NY 10036

awfulagent.com/ebooks

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Title Page

Copyright

Table of Contents

Book I: The Big Blind

Book II: Cloud Permutations

Part I

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Part II

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Part III

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Book III: The Vanishing Kind

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Book IV: Jesus and the Eightfold Path

Part I

Episode 1

Episode 2

Episode 3

Episode 4

Part II

Episode 1

Episode 2

Episode 3

Episode 4

Part III

Episode 1

Episode 2

Episode 3

Episode 4

Part IV

Episode 1

Episode 2

Episode 3

Episode 4

About the Author

Also by Lavie Tidhar

The Big Blind

1

CLAIRE SAID, ‘RAISE.’

She stacked chips. One pile, two, three. Started again. Not looking at the cards, not quite looking at the other players. Not not looking, either.

It was quiet in the small poker room at the back of the Dales. The sound of chips, the snap of cards on the felt. Cigarette smoke in the air, and someone coughed, someone else said, ‘One time, just one time,’ softly at another table.

Claire pushed the chips in, with a sort of careless studied gesture. They toppled across into the pot. It was a large pot.

The player on her left said, ‘All in,’ and pushed the remainder of his chips in. Immediately. But she’d expected him to do that. He had a short stack.

The rest folded, one after the other, until it came to the Docker. He was a short man and now running to fat but there was muscle under there. They said he used to work the docks. They said he did time in an English prison. They said all kinds of things. He looked at her. She looked nowhere, trying not to give anything away.

You never played the cards, as the old saying went, you played the players.

He took his time, but that was all right. He had a big decision to make.

She wished he’d get it over with, though.

‘A flush?’

Someone else said, ‘Only one way to find out.’ Someone else laughed, but quietly. The Docker shrugged and folded.

She turned over her cards and the short stack did likewise. The river was a three of hearts and she didn’t make the flush but her two pair still beat the short stack’s. He got up to leave the table.

‘Nice hand.’

She shrugged. The dealer shuffled the cards and dealt and round the table they went again.

* * *

There were three of them left after another hour. Her and the Docker and some kid, kind of cocky, with black curls of hair. He flashed her a grin. Nice teeth, and he knew it. He bet. She called, wanting to see the turn.

When the turn came it didn’t come her way but she had position and she used it, applying pressure, and the kid folded.

‘Hey,’ he said, ‘what’s your name?’

‘Claire.’

‘I’m Mikey.’

‘All right.’

He smiled again. He had an easy smile.

‘You’re good,’ he said.

‘I know.’

Even the Docker smiled at that. The next round he raised pre-flop, she folded, and the kid called. She took a sip of mineral water, watching the play. A raise and a call on the flop. She couldn’t read either of them.

On the turn the kid went all in. Quick call from the Docker. He turned his cards over. A full house. A look of disgust in the kid’s eyes. Turned his own over. It was a lower full house.

River came. It was a deuce of spades, no good to anyone. The kid got up.

‘Good hand.’

‘Yeah,’ the Docker said.

‘Mikey.’ The kid was looking her way again. Wore a new smile, like he had no care in the world. She thought maybe he didn’t.

‘Excuse me?’

‘Just in case you forgot. I’ll be seeing you?’

‘Why not, long as your money’s good at the table.’

The kid laughed. Then he went over to the bar and got himself a beer.

* * *

A few rounds later the Docker went all in on a semi-bluff and she called with a three of a kind but he got lucky on the river and with that the game was over. She collected her second-place winnings from Peg, the cashier.

‘How’s your dad, Claire? He’s not been round these parts for a while.’

‘He passed. Last year.’

‘I didn’t know. I’m sorry. Was it… ?’

‘It was cancer. It was… It was pretty quick.’

Peg touched her hand, lightly. ‘I’m sorry.’

‘Thank you.’

‘He was a character, was your dad.’

‘Yeah.’ She tried to smile. ‘He was.’

She took the money and turned to leave. Went past the kid, Mikey, necking a bottle of beer. Gave him a nod as she stepped out into the night, cold air, the smell of rain.

She pulled her coat around her and stepped into the drizzle.

* * *

She had to wait at the bus station for over an hour. She got a coffee and when she’d finished it she went into the bathrooms and changed into her habit.

* * *

The ride back was quiet. Her head rested against the window. It was another hour on the bus and dawn was just beginning to break on the horizon when they got to her stop. She got off.

There was no one around and the convent was quiet. She climbed over the wall and got in and went into the chapel and put the envelope with the money into the collection box and then she went up to her room. She lay on the bed, staring up at the ceiling, and fell asleep for an hour before waking up again for Vigils.

2

‘Raise, five hundred,’ Sister Bertha said. She pushed three red-topped matches and four burnt matches across the table into the pot. It was after Compline and the three of them were playing cards on the low table in Sister Bertha’s room.

Sister Mary looked at her, frowned, and folded.

‘Re-raise,’ Claire said. ‘Two thousand.’ She pushed across twenty matches, none of them burnt. Each was worth one hundred. Sister Bertha glared at her.

‘You’re bluffing.’

‘Only one way to find out.’

‘You think you can push me around, Claire?’

Claire shrugged. Sister Bertha drummed her fingers on the tabletop.

‘You’re bluffing,’ she said again.

Claire kept her face impassive. It didn’t do to underestimate Sister Bertha. Her play was aggressive and she was fearless. If she had anything, she’d call without qualms.

The question was: Did she have anything.

‘Why the big raise? Are you trying to push me off the pot?’

Nothing.

‘You have queens?’

Bertha had an uncanny ability to read the table.

‘Cowboys?’

Claire said nothing.

‘What do you have that could beat me?’

The longer they talked, the more likely they were to fold. Bertha was just trying to talk herself out of calling.

‘Oh, heck,’ Bertha said, and folded, at last. Claire turned over one card, and it was the Queen of Spades. She mucked the other one and smiled at the older woman.

‘Oh, heck,’ Bertha said. She took the cards and began to shuffle.

‘Mary, you’re the small blind,’ she said.

‘I’m almost out of matches,’ Sister Mary said.

‘Chips.’

‘I mean, chips.’

She had a quiet way of talking. She posted the small blind, two black matches. She only one had red match left.

‘Well, you’re still in the game,’ Sister Bertha said. ‘All you ever need is a chip and a chair.’

‘Where did you learn to play?’ Sister Mary asked.

‘Back room of my daddy’s pub.’

‘You play so well.’

‘Not as well as her,’ Sister Bertha said, and pointed her thumb at Claire. ‘I can play for matches. She can play for God.’

‘Do you think it’s wrong?’ Claire said. She said it quietly. Sister Bertha was laying down cards.

‘What?’

‘Do you think it’s wrong? To gamble?’

‘Gambling is not a sin, child. Avarice is. Do you play for the love of money, Claire?’

‘No. But I…’

‘You’d play if there was no money involved. You’d play for matches. You play because God’s given you a talent, and you use it.’ Sister Bertha smiled as she watched Sister Mary pick up her cards. ‘And besides, if poker really was just a game of luck, even Mary here might win a hand every now and then. Raise, one thousand.’

‘I fold,’ Sister Mary said meekly.

3

Claire chopped onions. She added them to the big pot. The onions sizzled as they hit the hot oil. Made her think about her father, coming back from a late-night session, walking in. He’d smelled of sweat and cigarettes and aftershave. He always dressed well for the games. Didn’t matter where the game was. A rich man’s home or a caravan park, the back room of a pub or the Legion. He always dressed the part and he often carried a gun. Back then, poker was illegal, and more than once he’d had to defend his winnings. When he’d come home he’d take off his jacket and roll up his sleeves and go into the small kitchen and cook. The smell would often wake her up. Fried onions, sausages. He’d sit at the kitchen table and eat his meal and she’d come in and get a hug, and sometimes they played a hand or two while he ate. Her father was never far from a pack of cards.

‘What am I supposed to do with these cuts?’ Sister Mary said.

The man from the chicken factory shrugged. ‘Beggars can’t be choosers, Sister,’ he said.

Sister Mary held up a hairless wing dangling between her fingers. Even from where she was standing, Claire could see the sheen of perspiration on the skin of the chicken.

‘Well?’

‘It’s not expired,’ the man said. He was more defensive, now. ‘It’s fine to cook.’

‘And anyway it’s nothing but skin and bones.’

‘Look, sister, what do you think I can do, here?’

‘Show compassion for the needy.’

The man shrugged, defeated. It was hard to argue with a nun. ‘It’s not up to me,’ he said tiredly.

When he was gone Claire helped Mary move the boxes. The smell of the chicken cuts wasn’t particularly pleasant. She and Mary did their best cleaning up the pieces – wings, necks, giblets. Claire added the wings into the pot and stirred them round. The necks they could use for soup. She added stock and potatoes and carrots that had come in from a donation the day before. They were lumpy, and had taken forever to clean and peel, but they would do.

It was warm in the little kitchen. Beyond the counter the regulars were already assembling. The television was on with the sound down low and a daytime talk show where people shouted at each other. Claire left the pot to boil and helped make tea. People always wanted tea. The town had been prosperous once, long ago, but with the mines all closed and only the chicken factory on the edge of town running, it was hard to make ends meet.

‘I don’t know what to do,’ Sister Mary said.

‘It can’t be that bad,’ Claire said.

‘It is,’ Sister Mary said; but she said it quietly.

* * *

They served lunch and everyone was very orderly and Marybeth Ryan came in with her new baby and everybody gathered round to coo at him. It was a little boy. When everyone’d finished and left home for the day, Claire and Mary cleaned up and Claire looked at all the tiny bones that were left on the plates.

It was hard work but it was satisfying, and she knew they helped people. When they finished they walked back to the convent, which lay on the outskirts of the town. She looked at the old building and she knew how rundown it was, and how the roof needed repairing, and how cold it got in the winter with drafts coming in and mould growing in the corners from the humidity. After Compline she went back to her room and lay down. She read a little from her book – Doyle Brunson’s Super System, an old favourite – but then she put it down and she fell asleep almost immediately.

4

‘I was playing this kid last night over at the Victoria, I raised with nothing, deuce eight off-suit, kid called, I got trip eights on the flop. Kid raised me, I raised him all-in, he called. Next thing you know I’m busted out when he made his flush. Just my luck, right?’

He looked at Claire as though expecting a reply.

‘So?’ she said.

‘So it wasn’t any fun.’

He raised and she called.

‘I didn’t see you there,’ he said.

‘So?’

He gave her a grin. ‘So if I did, it might have been more fun.’

Another night, another game. She paired her jack on the turn. Mikey was slow-playing his cards. Claire paired her queen on the river. She pushed a big bet. Mikey looked at her ruefully and folded.

‘Maybe not that much fun,’ he said, and she laughed.

She played tight for the next few hands. Mostly sitting them out. The cards weren’t going her way and she didn’t feel like mixing it up. This wasn’t an elimination tournament, it was a cash game. Patience paid.

‘Are you going to London?’ Mikey said.

She looked his way at the apparent non sequitur. ‘Excuse me?’

‘London,’ he said, drawing out the name.

‘What’s in London?’ she said.

‘The EPC,’ he said. ‘The European Poker Championship.’

‘Oh,’ Claire said. ‘No, I don’t think I am.’

‘Why not?’

‘Excuse me?’

‘I said, why not? You’re good.’

‘I don’t—’ she almost checked her cards then, even though she’d just folded. She gave him back a look, the sort that said Are you for real?

‘What’s your deal, Claire? I can’t figure you out.’

‘Are you going?’ she said.

‘It’s a five grand buy-in,’ he said.

‘I don’t have five grand,’ she said, and felt strangely relieved. So that’s that, she thought.

Mikey said, ‘There’s a satellite tournament in Dublin. If you win there, you win a seat at the EPC.’

‘Think you can do it?’

‘I know I can,’ he said. ‘I know you can do it, too.’

‘Well,’ Claire said. ‘I’m not.’ She pushed her chair back and collected her chips. Less than she’d hoped, but she’d just been grinding it tonight. ‘I’ll see you.’

He caught up with her as she was cashing out. ‘The satellite’s next week,’ he said. ‘I’m going to drive. You could come with me.’

‘I won’t.’

‘What are you going to do?’ he said, sounding genuinely exasperated. ‘Keep playing old men in dingy pubs for pocket money? You can play. You’ve got talent.’

‘It’s just a game,’ she said.

‘No!’ he said. ‘No, it’s not just a game, and you know it isn’t. I know you do, I can see it, the way you look at a player when they make a play, the way you study them. I can see the way only the tips of your fingers touch the cards, and how you don’t give anything away, and how your mind works when you’re figuring out the odds. For you, for me – it’s the game, Claire! There’s no other like it.’

‘Look,’ she said. He was making her angry. She wanted to push him. The Claire she’d been, before she heard the call… that Claire would have hit him. She used to run rough in the old days. Drink and smoke and get in trouble. She still knew how to boost a car. ‘Look, just leave me alone.’

‘All right.’ He took a step back from her and for just a moment he looked older. ‘But I’m going in three days, leaving early. I like it when it’s just before dawn. When the whole world’s quiet, and everyone’s still asleep.’

‘A poker player morning.’

He laughed. ‘I’ll wait at the tea hut by the bus station for an hour,’ he said. ‘Just in case you change your mind.’

She knew the place. It never closed. It was where cabbies and truck drivers and police officers all came to get a bite to eat at night. It was the sort of place every poker player knew. She nodded.

‘All right.’

She cashed and left. She thought about the EPC on the bus back, all the way back. She wasn’t going to go. It was just a crazy dream.

5

‘So you’re the mystery elf who’s been leaving gifts of money in the collection box.’

Claire, caught in the dark church with the envelope of money already through the aperture, froze.

‘Mother Superior,’ she said. ‘You startled me.’

‘Now, why, I find myself wondering,’ the Mother Superior said, ‘is one of my novitiate nuns skulking about before dawn, and sneaking out of the convent at night – yes, Claire, I know you haven’t slept in your room at all – and just where does she go, and from where does she return, with the smell of cigarettes and the city upon her and all this money in her pocket?’

‘Reverend Mother, it’s not what you think—’

‘Claire,’ the Mother Superior said, and sighed, ‘I have no idea what to think.’

‘I play cards.’

‘You play cards.’

‘We have no money to feed the people in the town and I know the convent’s been struggling and Sister Bertha says I have a talent and I just—’

‘Is that what Sister Bertha says?’ There was a quiet, dangerous tone to the Mother Superior’s voice.

‘No, it’s not like that.’

‘Does she know about your… excursions?’

‘No, of course not. No one knows… knew.’

‘You play cards?’

‘Poker. In the big town… I only did it because I thought—’

‘You wanted to help the convent.’

‘Yes.’

It was very quiet in the church. The Mother Superior paced, back and forth, back and forth.

‘Do you still wish to become a nun, Claire?’

‘Yes, of course! I want… more than anything—’

‘This is no way to go about becoming a nun.’

‘I’m sorry.’

‘Nuns do not lie. Nuns do not hide. Nuns do not play poker, Claire!’

‘I was just trying to h—’

‘This convent has survived perfectly well for centuries without your help, Claire.’

‘I didn’t mean… I just… Sister Bertha said there’s no shame in playing if it’s not for greed, and I—’

‘It seems to me Sister Bertha is a little too free with her opinions, Claire.’

‘Yes, Reverend Mother.’

‘Tell me something.’

‘Yes, Reverend Mother.’

‘This… This poker.’

‘Yes, Reverend Mother?’

‘Are you good?’

‘What?’

‘Are you good at it? I assume you must be, since, to be perfectly frank, your little donations are the most money this convent’s seen in years.’

‘Yes, Reverend Mother. I think so.’

‘And you say that while gambling is, shall we say, at best a grey area, which you feel yourself exempt from on account of your lack of greed—’

‘Reverend Mother?’

‘Do you enjoy winning, Claire?’

‘Winning?’

‘I assume you win at this game.’

‘Yes, Reverend Mother.’

‘You… You best your opponents.’

‘Yes, Reverend Mother.’

‘And do you therefore feel pride, Claire?’

‘Reverend Mother?’

‘You prove your own superiority over others. Do you take joy in it, Claire? Do you not feel that that in itself is a sin? The sin of vanity?’

‘Reverend Mother, I—’

She fell silent, then. The Mother Superior looked at her, and nodded.

‘Quite,’ she said. Her tone softened. ‘I appreciate what it is you wanted to do, Claire. But you have to choose. You can be a card player, or you can be a nun, but you can’t be both. When you came to me, when you said you heard the call – I thought I saw something in you. The makings of a nun. You have a good heart and a practical head, and you need both, but there is no shame in turning back. The world, after all, is filled with women who have not taken the vows. I know you had a troubled time before you came to us—’

‘I did, but Reverend Mother, I do feel it. The convent isn’t an escape for me. The things I did, I did because I didn’t know where I was, what I wanted. Then I felt it. I felt the call. I know it’s real. I was wrong to deceive you. I was afraid to come to you, before. But I was just trying to help.’

‘Get some rest,’ the Mother Superior said. ‘You have Church History in two hours.’

‘Thank you.’

‘I will pray on this,’ the Mother Superior said.

6

‘What the—’ Mikey said. He came into the mission with Bill Hanlon, who lost one of his legs in the mines.

Claire looked up and felt herself blush. She couldn’t help it. Mikey stared at her habit.

‘You’re a nun?’

‘A novice,’ she said. Mikey raised his arms and let them fall. She almost laughed. He looked like a gutted fish.

‘Show some respect, lad,’ Bill Hanlon said. He pushed himself forward on his crutches, to the counter. ‘Good afternoon, Sister.’

‘It’s good to see you, Bob. How are you holding up?’

‘Oh, you know. How long is a piece of string?’

‘A nun?’

‘Lad!’ Bill Hanlon shook his head at Claire, mournfully. ‘Kids today.’

‘You related?’

‘My nephew. He’s a bum.’

‘Hey!’

‘Plays cards all day, say it’s work. Did you ever hear anything more ludicrous?’

‘Come on, Uncle Bill. I’ll buy you lunch somewhere proper.’

‘Watch your tongue, lad. This food’s blessed by God. What’s for lunch, Sister? I pray it’s liver and mash again.’

‘It’s liver and mash again.’

‘Hallelujah! See, lad? God provides.’

He pushed himself to a table and sat down, staring intently ahead.

Claire looked at Mikey.

‘So?’

‘No, nothing,’ he said. ‘I thought…’

She motioned him to come closer. He edged forward, looking embarrassed. ‘I offered to buy him lunch in the café but he thinks I stole the money, or something.’

‘Listen,’ Claire said. She was speaking softly, and Mikey had to lean forward to listen, so that their heads almost touched.

‘Yes?’

‘This EPC thing, in London.’

‘Yes?’

‘How much?’

He knew what she meant, of course. A little bit of the smile came back to his lips.

‘A million for the winner.’

‘A million pounds?’

‘Poker’s big business, now. It will be on television, and everything.’

‘Television poker,’ Claire said, with just a hint of dismissal.

‘They say anyone who’s anyone’s gonna be there. Negreanu, Ivey, Harman…’

‘Television poker,’ Claire said; but she sounded less convinced, now.

‘And six hundred thousand for second place.’

‘That’s a lot of money.’

‘It’s not even about the money, though, is it. I mean, not just the money. It’s the winning, it’s getting the trophy. It’s sitting down at the table with legends, Claire. And then getting the chance to bluff them.’

‘With your tells?’

He laughed, but it was a nervous sound. ‘I don’t have any. Do I?’

It was her turn to laugh. Sister Mary came around then with the big pot and Claire had to move away and help her with it. Later, she watched Mikey and his uncle eat. Bill Hanlon saw her looking and gave her the thumbs-up. As they were leaving, Mikey came over to say goodbye.

‘My offer still stands,’ he said. ‘Sister.’

She shook her head.

‘I’ll see you.’

‘I don’t… I’m not coming back,’ she said. ‘It was a mistake.’

Mikey’s expression was hard to read. His poker face.

‘God moves in mysterious ways,’ he said.

7

One day, about a year before she’d joined the convent, Claire didn’t go with the others to the rooftop of the old estate, saying she had an errand to run, though she didn’t. They often sat on the rooftop, amidst the old mattresses and broken bicycles and discarded cans, and they’d drink cheap ale, and smoke and watch the hazy sun behind the clouds and over the city, which could be very beautiful sometimes, but more often than not all you could see were the ugly concrete buildings and maybe a couple having a fight inside a flat, glimpsed through a window. It was the sort of place where people dumped their old cars because it was cheaper that way.

That day she didn’t have an errand to get to. She just walked, without a clear destination in mind, listening to music streaming in through her earbuds. It was cold, she had her parka drawn tight around her. She’d been up too late the night before. Everything looked both too bright and too hazy, and she almost got run over when she tried to cross the road and didn’t notice the car coming. A lot of her father’s old poker buddies showed up to the funeral and, later, during the wake, they’d set up a game in the living room, and as much as it annoyed her mother, she didn’t tell them to stop.

She was just walking around, aimless, when she saw the church. It started to rain and she went inside. It was very quiet, with barely anyone around. She lit a candle for her father and then she went and sat on the pews, a few rows from the altar, to the side. There was a very beautiful stained glass window overhead and it diffused the murky sunlight from outside and she could hear the rain knocking against the glass.

She’d felt something, then. It wasn’t something you could put in words. Just a feeling she had. For a moment it was like her father was sitting beside her, on the next pew; not saying anything, but smiling. It was just a coalescence of light and shade. But the feeling persisted. It was very peaceful, and she felt loved. She left the church smiling, and the feeling stuck with her all the way back to the house.

8

‘I understand, Your Grace,’ the Mother Superior said, in tones that nevertheless made it quite clear that, if she did, then at the very least she did not agree with the pronouncement. ‘But there must be something we can do.’

Claire had passed by the office and overheard the voices and some instinct made her stop. The door was slightly ajar and the Bishop and the Mother Superior were inside.

‘Numbers don’t lie,’ the Bishop said. He had a pleasant baritone voice and she’d heard he was a good singer back in his day, in the choir, but now he sounded tired, and a little exasperated. ‘And we don’t have the money to spare, Reverend Mother. We’re going to have to foreclose to the bank.’

‘But the convent! And all our work in the town!’

‘We both knew it was coming down to this,’ the Bishop said, and his tone was gentler now. ‘This is not a surprise to either of us.’

‘I won’t accept it.’

Claire could hear the Bishop pace inside.

‘What do you want me to do?’

‘Give us a stay of execution, something—!’

‘I already have. Reverend Mother, I have no more cards up my sleeve. Everyone’s struggling. Even the church.’

‘How long do we have?’ She sounded defeated.

‘I’ll see what I can do… maybe a month.’ Claire heard the sound of his footsteps, approaching the door. His shadow fell on the lit open space in between the room and the corridor, as though it were eager to escape.

She walked on and heard him step out behind her. A few more words were exchanged, but she didn’t hear what they said. When the Bishop was gone Claire doubled back. She knocked on the door.

‘Yes? Come in. Oh, it’s you.’

‘Reverend Mother.’

‘What is it, Claire? I am a little busy.’

She did look busy, and tired, sitting behind her desk, glasses perched over the bridge of her nose, accounts sheets hopelessly spread before her. The pads of her fingers were smudged with blue and black ink.

Claire said, ‘It’s about what I was doing, the money—’

‘I told you, that is no occupation for a nun.’

‘But we need it, don’t we? We need it, and there’s this thing coming up, and I think—’

But the Mother Superior shook her head. ‘God will find a way, and a nun’s a nun,’ she said. ‘Claire, you need to decide what you want to be, and it isn’t a decision I, or anyone else, can make for you. Do you understand?’

Claire nodded. She understood.

‘Goodnight, Claire.’

‘Goodnight, Reverend Mother.’

She left her there, to her accounts.

9

You’re doing the right thing, Claire.

You’re doing the wrong thing.

You’re doing the right thing, but for all the wrong reasons.

You’re…

10

She had the sleep cycle of a professional poker player or a novelist, people who were more comfortable in a dark bar at 4 a.m. than they were getting up for work or Matins. But she was still young enough that her body could take the cycle shift and she could still go entirely without sleep if she had to. But the secret night runs to the card room had exhausted her.

She cared about the people they helped and she cared about serving God, and it wasn’t something you could explain, it was just something you either felt or you didn’t. All she knew was that her life was better for it, and now she was going to throw it away.

Early dawn at the bus station, and outside the little tea hut two policemen, and a truck driver, and one of the regular homeless guys, were standing each on their own like little islands, drinking tea or digging into bacon butties. She stood there, breathing in the cold air, traffic fumes, the smell of frying onions. In the old days she would have lit a cigarette, to keep her company. What had she called it when she spoke to Mikey? A poker player morning.

‘You came.’

She turned. He stood there in the pool of light under a streetlamp. His black locks of hair looked wet, he must have scrubbed himself up in the station’s restroom.

‘I didn’t think you would.’

‘You want a cup of tea before we go?’ she said. ‘It’s a long drive.’

‘Sure.’ He was still standing there, just looking at her.

‘What do I call you?’ he said.

‘Claire.’

‘Alright.’ That old smile came back to him. ‘Well, tea sounds nice.’

They went and stood with the others and she ordered and paid. She also bought a couple of bacon butties. She had hers with brown sauce and he had his with ketchup.

11

The sun rose as Mikey drove. The roads were pretty quiet. The land beyond the window was very green. Occasionally they’d pass a village or a town, or cows in a field, or a castle.

‘See that structure over there?’ Mikey said, pointing. Claire looked out of the window, at a rounded sort of house on a hill. It looked like a big Gothic ruin.

‘Yes?’

‘It’s a folly,’ he said. ‘It’s decoration. They built it to look just like that.’

‘So it’s like a bluff,’ she said, and he laughed.

‘Yeah. It’s an architectural bluff.’

Mikey’s car was pretty old and beat up but it ran ok. They listened to the radio. They stopped at a service station and had a coffee.

‘I played Donnacha O’Dea once, you know,’ Mikey said.

‘The Don? What was he like?’

‘Took all my money.’

She laughed.

‘He has a bracelet, doesn’t he?’ she said. She meant the World Series.

‘Yeah.’

‘Show it to you?’

‘No.’

As they continued driving the roads became busier, and Claire rolled down the window to half open and let the cold wind on her face.

‘You ever think of going?’

‘Where?’

‘The World Series.’

‘I guess I thought about it, before… You know.’

‘I don’t really,’ he said. ‘I still don’t get—’

‘What’s to get?’ she said.

‘A nun?’

‘A novice nun. And I don’t know if I still am, now. I… Look, do you mind if we don’t talk about it?’

‘You mean the World Series?’

She had to smile.

‘You want to go?’ she said.

‘One day. I have to. It’s the dream, isn’t it? The Main Event. Be up there on the wall with Ungar and Doyle. Johnny Chan. You know.’

‘I guess.’

‘You could do it.’

‘Your faith in me is touching.’

‘Got to have faith. Sister.’

‘I told you,’ she said, and she drew her hoodie tighter over her head. ‘It’s Claire.’

‘Alright.’

They drove in silence for a while, listening to music on the radio, until Dublin came into view ahead.

12

‘Claire? Oh my God, Claire? You’re home!’

‘Hi, Mum.’

The hug was bone-crushing. Her mother pulled her inside. The flat smelled of frying oil, cigarettes, floor polish, her mum’s perfume, and something delicious on the stove.

‘What are you doing here? I thought you were at the… you know.’

‘It’s a long story.’

‘I’m so glad! I knew it wouldn’t last, a lass like you, in that place.’ Her mother crossed herself. ‘Nothing against the Church or those nuns, wonderful people, wonderful, but it’s not right, not for a young person like you… will you be staying?’

‘Is Kevin still here?’

‘You know he is, honey.’

‘Then no.’

‘Oh, Claire. I thought we moved past this.’

Claire shrugged. She didn’t want the fight but now that she was here it all felt so inevitable, like a soap on TV that she’d watched too many times. Her mother loved soaps.

‘Only a few days, then,’ she said.

‘Can I fix you something to eat?’

‘What’s that smell?’

‘Beef stew and dumplings.’

‘I guess.’

‘Come on…’ Her mum took her hand and dragged her to the sofa. It was brown and worn. ‘Sit down, sit down. I’ll put the telly on.’

13

‘So, what’s it like? The convent?’

‘Leave it alone, Kevin.’

‘Don’t you talk to him like that, Claire.’

‘How do you want me to talk to him, Mum?’

‘Show some respect.’

‘It’s alright, Kate.’

Something about Kevin irritated Claire beyond words. It wasn’t that he was a bad guy. He had a steady job and he treated her mum well, but maybe it was just that he tried too hard. Or maybe it was just that he wasn’t her dad. She got up and got her coat.

‘I’m going out.’

‘Claire…’

‘It’s alright, Kate.’

‘When will you be back?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Claire, this is my house, you will show me and Kevin r—’

She slammed the door on her way out.

14

There was just something about being back that felt so suffocating. She didn’t know who she was anymore, or who she was going to be. She tried to ask God but, for the moment at least, she just couldn’t find an answer, so she did what she at least knew she could do well. She went to the poker room at the casino.

15

The satellite tournament was pretty lively. There were around two hundred entries, and she was playing pretty well – she got an early all-in and doubled up and she was having a good run, steadily accumulating chips. Her dad used to play the early TV poker shows, he got in second on that Poker Pros and Celebrities Tournament back in the day, and he enjoyed the attention, being recognised by the boys down the pub and that sort of thing, but what he’d always said to her was, there’s TV poker and then there’s real poker, and by real poker he meant the cash games. A pro played for money, and the money was always in cash games. It took her a while to get used to tournament play, it was faster and looser, everyone wanting to double up quick or get busted. There weren’t many women playing – there never were. They kept rotating the players around the tables and she ended up playing a few hands with Mikey before they got rotated out each to another table. By the end of play they were down to just over fifty players.

‘Having fun?’

They were at the bar where a few of the others congregated. She stuck to water and Mikey was having a soft drink. It didn’t do to drink before the next day of playing.

‘You should get some sleep,’ she said.

There was something in his eyes, for just a moment, then it was gone. ‘Think you’ll make the final table?’ he said instead.

‘Or win.’

He laughed. They finished their drinks and she went back to her mother’s. She unlocked the door and came in quietly and tiptoed to the sofa, where her mum had left her a blanket and pillows. She curled up on the sofa, trying to calm down from the rush of the game, but she kept running poker hands in her mind. She said her prayers and tried to sleep. She missed Sister Mary and Sister Bertha and her room, and the quiet of the chapel, and the work. She missed her dad, too, but that was the sort of loss that lingered, and had been there a long time. The flat was full of his memory. She fell asleep at last, thinking about the time he took her to see the Big Game.

16

There is always a Big Game somewhere. It’s never in the news, and it’s never recorded in any official poker ranking or tournament winnings or any of that stuff. There’s always been a Big Game and there will always be a Big Game, and a good pro always makes sure to know where to find it.

For this one, her dad took her to the bank. He had two safety deposit boxes. He’d always said, the best place to keep your money was in the bank, but not in the bank. In the first box he had thirty thousand pounds in cash, and in the second there was a diamond brooch he’d won in a game somewhere. They took both and went to a little shop off O'Connell and there he spoke quietly with the proprietor and the brooch was exchanged for more cash.

The Big Game that time wasn’t the sort you take a gun to, but it was the sort you might want to put a tie on for. It was in one of the big houses in Ballsbridge, and she’d never seen a place like that before, it was done in a minimal style with artwork on the white walls, and big glass windows that opened onto a private garden and a heated swimming pool. The game itself was eight men, including her father. They all took it seriously. No one was drinking apart from the one guy sipping a glass of Midleton 30 Year Old. A couple of the men were smoking cigars, which she supposed was what men did. She didn’t mind the smell so much. No one seemed to care she was there. She sat by her father, mostly, and watched. After a while the rhythm of the game started to make sense, she could see which player was tight, which one was betting aggressively on nothing, which one was going on tilt when he lost a big hand. Her father played the game like he played any other game. He didn’t let the money distract him. The room was quiet but for the sound of the chips hitting the pot. The dealer was a professional, she was a woman in a black tailored jacket and tie, she must have been hired from the casino. Claire got the impression her father knew the dealer but then, her father knew most people in that line of work.

Her father played a couple of big pots and lost both and his stack got short for a long while, but he didn’t let it faze him, he kept playing and he built it back up. When they left they were about ten grand up from when they’d started. The next morning he drove her back to the same little shop as before and they got the brooch back plus a little gold necklace for her mother, and a pair of earrings for Claire, and then they went back to the bank and put the money and the brooch back into the safety deposit boxes.

She knew it took hard work to build up a bankroll and it only took a moment to lose it, and like all players her father had gone bust more than once. Her mother hated the game and everything about it. But she guessed her mother still loved her dad, all the same.

17

It was late afternoon when the satellite started up again. There wasn’t a bubble, as such, in this one. You played for a chance at the Big Game and that was that, you either made the cut or you went home empty-handed. She woke up with a headache but it was gone when she stepped into the casino. She took her seat next to Tuco, a grizzled old man who’d been a friend of her father’s, and knocked him out a few hands later when he went short stacked all-in with a pair of sevens against her ace-five. She got an ace on the turn and that was that for Tuco.

The field shrunk to thirty-two, then nineteen, the blinds going up, and up, and up. She kept her cool, avoided going all-in, mixed her play. She kept growing her stack. The field shrunk, a double knockout brought them down to seventeen. Then twelve, two tables left. Mikey was still in, though he had a shorter stack. He knocked out another short-stacked player and doubled up. Ten players, then nine, then eight…

Then there were seven, and at last they had a final table. But only the players who finished in the top four would get the comp entry to the championship in London. It felt more focused, sitting the final table – there was a large audience all around them by then, and she wasn’t used to that, and it could have been a bit intimidating but she tried not to let it tilt her and just focused on the game. Number seven got knocked out and then six. Claire raised big with a five-six of hearts under the gun and it got folded to the big blind, who called. The flop came ace, queen, deuce, with two hearts. The guy on the big blind wasn’t going anywhere and she stuck around and hit a heart on the river and picked up the pot against the guy’s ace-queen. He got knocked out a few hands later by another player and then they were four and Mikey let out a whoop that had everyone laughing – they were in. Claire got knocked out at third place and Mikey at two, and some guy got a trophy but they didn’t stick around to see him waving it around. They had their ticket to the Big Game and that was what they’d to play for.

* * *

‘I’m sick I didn’t win, though,’ Mikey said. They were at a bar away from the casino, somewhere there weren’t any other players. Mikey was drinking a beer and Claire had a glass of rum and coke.

She said, ‘We got what we wanted.’

‘Sure, but—’

‘You want the fame.’

He laughed, a little self-conscious. ‘I guess so. A little bit.’

‘It’s vanity.’

‘There’s nothing wrong with being a little vain.’

‘It’s a sin.’

‘This really bother you?’

‘I don’t know. I guess so.’

‘Then why do you play?’

‘For the money.’

‘So greed?’ he said, and he sounded disappointed. ‘Isn’t that a worse sin?’

‘No,’ she said, ‘I mean, for what the money can do.’

‘Isn’t that what anyone greedy would tell themselves?’ he said.

‘No. I don’t know!’

‘This bothers you, huh?’

‘I guess it does.’

‘Then go back,’ he said.

‘I can’t. Not now.’

‘Look,’ he said. ‘What’s so great about being a nun, anyway?’

‘It’s a calling,’ she said. ‘It’s not something you can run away from.’

‘I’m guessing you used to run away from a lot of things,’ he said. She stared at him over the rim of her glass until he raised his arms in mock-surrender.

She felt reckless. They ordered more drinks. He really did have beautiful eyes, she thought, and she felt that feeling in the pit of her stomach, that sort of slow melting gold, and she shivered.

* * *

Under the awnings of a shop, later. They staggered down the road and she swayed until he caught her in his arms. She pressed into him, feeling his warmth. Their faces were suddenly close together.

‘Claire…’ he said. She could hear the sudden hoarseness in his voice.

For the briefest of moments, their lips touched. Barely touching, just brushing each other. Then they pulled away.

‘Claire…’

‘I’m celibate,’ she said.

‘You don’t have to be.’

He really did have beautiful eyes, she thought. She ran her fingers in his thick hair. Touched his cheek, for just a moment.

‘I know,’ she said. Then she pulled away from him and walked away. She only walked a few steps and then turned and looked at him. He stood there shaking his head, and then he laughed, and she laughed too.

‘I’ll walk you home,’ he said.

18

‘A poker tournament? You play poker now?’

‘Mum…’

‘No, Claire! I won’t let it go. Playing at being a nun, that’s one thing, I didn’t want you to but I thought, she’s bound to get bored of it, she’s got bored of everything she’s done so far, how long can it last – and I was right, too, wasn’t I? Seeing as you’re here and all—’

‘Mum!’

‘But cards? Baby, I lived with your father for years! Dodging creditors, moving from one shabby flat to the next, never knowing if tomorrow we were going to eat in the fanciest restaurant in town or not have money to pay for the milk. You don’t remember any of this, do you? You were small, and anyway you always worshipped him. He could never do wrong in your eyes. While I fed you and cleaned you and kept you warm and kept the house – kept his house, so he could come home at any time of the day or night, which he treated like a hotel, all so he could go back out again to play cards. Do you know—’

And out of nowhere, there came to Claire a memory, one, it seemed to her, she had forgotten, until this moment: an evening, long ago, and she was sat in front of the television, on the sofa, while her mother cooked. There was a knock on the door, a harsh fast sound that repeated, until it seemed to her it was not at all knocking but someone banging on the door, demanding entry. And her mother went to open it and two men barged in, and the shorter of the two pushed her mother until she almost fell, and Claire thought her mum would go for him then but she didn’t; she kept back.

‘Where is he?’ the bigger man demanded. Claire had got the impression her mum knew him, that he’d been around before, though she didn’t remember him.

‘He’s not here.’

‘I can see that.’

‘What do you want, Jake?’

‘You know what we want.’

‘It ain’t nothing to do with me.’

‘This is his house,’ the man said. ‘These are his things.’

‘You leave it alone!’

‘Ain’t up to me, Kate. It’s more than my job’s worth.’

‘Don’t touch that!’

But this Jake, and the other man, began looking through the house, opening and shutting drawers, looking under cushions, and in the kitchen and even the bedroom – looking for money, she knew, even then. And when they found none, they took the television, and Claire started to cry, and the big man said, ‘There, there, little girl—’ awkwardly, but his assistant said nothing to her at all. Together they carried the television through the door and out, and in parting, the big man said, ‘And tell him if he doesn’t come up with the rest by Tuesday…’ and left the rest of the sentence unsaid.

And Claire remembered her mother crying, suddenly and without warning, and without making a sound, but covering her face with her hands so her daughter wouldn’t see her. And Claire remembered going to her mother and trying to hug her, and her mother pushing her away, until she relented, and extended her arms and held Claire close to her. And she remembered the tears were hot, and theyopyfell on her face, until she was crying too.

‘Claire, are you even listening to me!’

And she woke. She had been packing her bag when her mother came in. And now she went up to her, Kevin watching awkwardly the whole thing, no doubt wishing he was somewhere else, and she hugged her mum, just like that time, and her mother tried to push her away, and then relented. And so they stood there like that, holding each other, and Claire realised she was just taller than her mother now; as though her mother, in the intervening years, had shrunk. And she said, ‘I love you.’

‘I love you too, baby. You know I do.’

‘And I’m sorry. For everything.’ She pulled back, and she picked up her bag off the sofa. ‘But I have to go.’

‘Claire? Claire!’

But she was gone, the door shut softly behind her.

The next stop, she thought, would be London.

19

Day 1.

Lights…

Camera—

Action.

* * *

‘Welcome to the glitz and glamour of the Royal Hotel in the heart of London, and to the first ever live-televised European Poker Championship! With an entry fee of £5,000 and a whopping first place prize of a cool one million pounds, this is the must-be – and must-see! – event of the yea—’

Talking heads in a booth, Donald “The Duck” McPhee and Mike “The Mouse” Markosian: a popular double act on the TV circuit, she’d seen them on countless episodes of Late, Late Poker and Vegas High Stakes and The Circuit. She knew they’d be up there right now waiting for the edited footage from the actual game play to start rolling and, meanwhile, record commentary on the players as they began to come in. She went up to registration and queued up with the rest and when she got her bag of chips she just stood there, for a long moment, with a stupid grin on her face, until someone told her to move it.

She hefted the bag: five thousand points in chips.

This is it, Claire, she thought.

She went into the main hall to find her table.

* * *

It rained during the ferry ride to Manchester, and it kept raining on the long bus journey to London. As the bus began to wind its way through narrow streets of grey-brick buildings, early dawn came and the rain became a sort of thin drizzle which turned at last into a mist with the consistency of runny gruel. It wasn’t properly cold, it was a sort of clammy damp that couldn’t quite make up its mind what sort of weather it wanted to be so had just decided to be as unpleasant as possible on general principles.

She did get to see the Houses of Parliament, in the distance. At least she thought that’s what they might have been.

The satellite win only covered the Main Event entrance ticket. Claire booked into a cheap hotel off Edgware Road. It was the cheapest she could find and it still cost more than a round-the-world backpackers special for two. It cost more than the gross domestic product of Tuvalu. It cost more than a cocktail at Rules. It cost… anyway it wasn’t cheap.

And it was a long way to go into the money.

That was the thing about tournament play. The vast majority of players never finished in the money. Their entry fee went into the pool, and then they were knocked off, one by one by one, victims to low pairs and weak aces and bad bluffs and busted flushes. Most of these players stayed the course, keeping the dream alive, sitting for hours playing hand after hand, mucking, raising, calling, going all-in… busting out.

Until, at last, you hit the bubble.

Once you were in the bubble the remaining players got paid. How much you got paid depended on how deep you ran. And then when you hit the final table… that’s when the big payouts began.

So all you had to do, Claire figured, was get through the field of a thousand or so of the best poker players in Europe, if not the world, all gathered together in one convenient ballroom, and you were scot free. As her father would have said, it was as easy as falling off a log.

So, it was that… that, or bust out half an hour into the main event and go back to Ireland with nothing but the coat on her back, and a memory of the Ballymoon Hotel and its dirty carpets, shared toilets at the end of the corridor, and the strong smell of hash lingering not entirely unpleasantly in the air. She’d seen worse, just never at the prices the Ballymoon charged. That part was pure London.

In any case it was only a place to put down her stuff and kip for a few hours. The rest of the time she’d be in another world.

It was a short tube ride to the Royal and when she climbed the marble steps and walked through the double doors it really was another world. It was the sort of place that had chandeliers hanging from the ceiling and carpets thicker than a boy from Cork, as her father used to say. It had a sort of slightly shabby, genteel opulence. But really all anyone cared about that day was the tournament.

The thing was, there’s nothing opulent or otherworldly about even a place like the Grand Hall when you have to shove a shedload of card tables and chairs into it. With the number of registrants, it was all anyone could do to barely move between the tables, and by the time the ballroom filled up with players the air became noticeably warmer, and turned somewhat fragrant with bodily odours as the day progressed. But none of that really mattered. Not as soon as they’d dealt the first hand of cards.

* * *

‘Shuffle up and… deal!’

* * *

Suited connectors, seven-eight of hearts, out of position. She mucked. But as soon as they got dealt she felt she was herself again, and she was in control.

* * *

Never play the first hand in a tournament, said Doyle Brunson. And could that man sitting hunched at the next table, a wide cowboy hat on his head, his posture as accustomed to the chair as only a professional gambler’s could, really be Texas Dolly? And over there, checking her phone while listening to music on her ear buds, was that Nicola “Kicker” Sinclair, two-time EPC champion, who got her nickname when she defeated Vladimir “The Impaler” Walewski at the Berlin EPC with nothing but a queen kicker to his jack?

‘They’ve come from all over the world, drawn to the crown jewel of the EPC tour, the London event. And, as usual, we like to take an early look at the contenders – what do you think, Mike? Anyone who catches your eye?’

‘Well, Don, the last person to catch my eye was my last ex-wife, and I’m still paying that one off. But sure, there are some strong players here in the field – Jennifer “Pocket Jacks” Jackson is here—’

‘That’s a hand no one should ever play, Mike—’

‘Well, you and I shouldn’t be allowed anywhere near a card table, Don, but in Jennifer’s hand, a pair of jacks may as well be quad aces every time.’

‘A dangerous player, indeed, Mike.’

‘Then there’s the Impaler, Don. A young player—’

‘Aren’t they all, Mike?’

‘They do seem to be getting younger and younger every year, don’t they, Don? But Vladimir Walweski, a young Polish-German player, has been making a name for himself on the EPC circuit, and you remember him, of course, from last year’s WSoP, where he’d made a deep run at the Main Event—’

‘An impressive performance—’

‘A player to watch, that’s for sure. Very loose, very aggressive, my bet is he’ll either bust early or make a deep run again. I wouldn’t be surprised to see him at our Final Table—’

‘We’ve talked about the pros, Mike, but what about the amateurs?’

‘Well, Don, with just over a thousand entrants, there are plenty of hopefuls in this tournament, young guns and grizzled old players emerging victorious from home games all across Europe. Who’s to say who will triumph, and who will fall? It’s Day One of the Main Event, and if we know just one thing, it’s this: everything is possible.’

‘All you need is a chip and a chair, eh, Mike?’

‘That’s right, Don. That’s r—’

She saw Mikey, at another table, but he was in a hand.

What was incredible was just how quickly some of the players just went for it. Within the first twenty minutes at the table she saw two guys go all-in against each other pre-flop, ace-king against a pair of jacks. It was a classic coin toss, and the flop came seven-ten-three rainbow, a very good flop for jacks, and the turn wasn’t any help either but a king came on the river and the jacks busted out. Five thousand pounds, she thought, just to play for twenty minutes. And this was going on all across the tables, players were getting up and moving on, to the side games, and the remaining players kept being shuffled around to other tables as empty ones were removed, one and then two and then three, but there were still plenty of players left. It was a massive field, and the key to surviving it was to play well and to be patient. The blinds were still low and a lot of people just kept mucking their cards, waiting for a real hand to push with, and Claire was beginning to get a sense of the other players’ rhythm and the way they played, when she got moved to another table.

‘Hello, Claire. Long way.’

…and found herself sitting across from the Docker.

‘Docker. Didn’t realise you played tournaments.’

‘Don’t, usually. Don’t like the cameras.’

He bet, half the size of the pot. On his left, a boy in a hoodie that left nothing visible of his face but his eyes, which were themselves obscured behind dark sunglasses, looked at him sideways and folded.

‘So what’s changed?’

She called with her pocket sevens.

‘Money,’ he said.

‘Money?’

‘Money’s bigger.’

It was a long conversation, for the Docker.