Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc.

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Serie: The Bookman Histories

- Sprache: Englisch

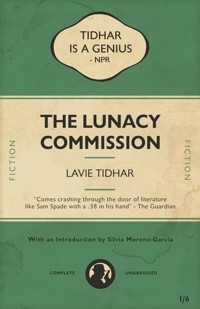

In the last decade of a 19th century unlike our own, Milady de Winter is called to the scene of an impossible crime. A gruesome murder on the Rue Morgue sets her against a ghostly serial killer, and on a voyage that leads from the catacombs of Paris to the wonders of the New World – where new horrors lie in wait. In Camera Obscura, World Fantasy Award winner Lavie Tidhar combines the Victorian penny dreadful with exploitation cinema to create a wide-screen thriller of redemption: complete with mad scientists, secret societies, Shaolin monks and figures liberally borrowed from the literature of the era – as only he can. "A rollicking adventure...a maelstrom of pop culture and recursive fantasy." – Tor.com "Superb." – Fantasy Book Critic

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 457

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Camera Obscura

Copyright © 2010 by Lavie TidharAll rights reserved.

This edition published in 2025 by JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc. Originally published in 2011 by Angry Robot.

Cover art © Copyright Sarah Anne Langton 2016

ISBN 978-1-625677-66-2

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places and events are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc.

49 W. 45th Street, Suite #5N

New York, NY 10036

http://awfulagent.com

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

Part I

1. A Woman With a Gun

2. The Corpse

3. A Spark of Electricity

4. Outside Rue Morgue

5. Across the River

6. The Immaculate Mr Thumb

7. Imports & Exports

8. Tattoos

9. Notre Dame de Paris

10. Into the Catacombs

11. The Under-Morgue

12. The Quiet Council

13. The Little Grey Cells

14. Post-Mortem

15. Place Pigalle

16. Microcosm

17. Broken

18. The Clockwork Room

19. Projections

Interlude: Jungle Fever Boy

Part II

20. Shaolin & Wudang

21. Moulin Rouge

22. Toulouse-Lautrec

23. Yong Li

24. Taken

25. The Empress-Dowager’s Emissary

26. Fat Man and Lizard

27. The Goblin Factory

28. The Unfortunate Demise of Tom Thumb

29. The Grey Ghost Gang

30. The Toymaker

31. The Code of Xia

32. Master Long’s Story

33. Lord of Light

Interlude: The Other Side of the River

Part III

34. The Woman in the Mirror

35. Ampère

36. The Lizardine Ambassador

37. The Electric Ball

38. The Fat Man

39. The Phantom

40. Rise of the Jade Grey Moon

41. What Transpired at the Montmartre Cemetery

42. I am Pain

43. Grimm

44. The New Translation of Lady de Winter

Interlude: Kai Wu Unrolls His Mat

Part IV

45. Charenton Asylum

46. Citizen Sade

47. The Sound of Drums

48. Escape from the Insane Asylum

49. The Return of the Phantom

50. The Message

51. Onwards to Vespuccia

Interlude: The Lean Years

Part V

52. Cargo

53. The Unfortunate Death of Flies

54. Captive of the Waves

55. Infected

56. Lights

57. Scab

58. Waldo

59. Descent

60. Glass Coffin

Interlude: The New World

Part VI

61. A Bowl of Hokkien Noodles

62. The Black City

63. The Message

64. Winnetou

65. Top of the World

66. The Monsignor

67. Holmes

68. The Phantom’s Maze

69. Qinggong

70. Dismissed

Interlude: Moving Pictures

Part VII

71. The Magician of the Fair

72. The Auction

73. The Wheel

74. The Gateway

75. Lights

About the Author

To Elizabeth, always

“Even if my readers are too well informed to be interested in my descriptions of the methods of the various performers who have seemed to me worthy of attention in these pages, I hope they will find some amusement in following the fortunes and misfortunes of all manner of strange folk who once bewildered the wise men of their day. If I have accomplished that much, I shall feel amply repaid for my labour.”

Harry Houdini, Miracle Mongers & their Methods

Prologue

The Emerald Buddha Massacre

The young boy huddled in one corner of the house, half-reading a wuxia novel and half-keeping watch on the night. The night was very still. Outside only the barest hint of wind rustled in the coconut trees, and the air was thick with humidity and the promise of rain.

There were few lights.

Mr Wu’s Celestial Dry Cleaning Emporium stood on the very edge of Chiang Rai, stooping like an aged uncle on the border between city and jungle. Mr Wu was standing behind the counter, rolling a cigarette. His hands were liver-spotted and shook a little, dropping bits of loose tobacco on the counter. It took him three tries before he managed to light the match. The cigarette glowed like a firefly in the dark.

On his stool, the boy was reading about heroes and villains. There was a girl, a beautiful assassin, and a man she had to kill, travelling a great distance to find him. There were others like her, all seeking the man they had to kill. The boy’s name was Kai. He was reading by the light of a fat, half-melted candle. He put down the book and listened. Somewhere in the distance thunder sounded. The light from Mr Wu’s cigarette traced unpredictable orbits in the darkness. “You stay here,” he said to the boy. Then he went to the open door and stepped outside, into the night.

Kai listened but could hear nothing. He put down the book, assassins and chases abandoned for the moment, and stood up. Quietly, he too went to the door. He peered outside.

A thin yellow moon cast strips of light and shade on the street, bands of yellow light cut in stark relief with hard lines of darkness. Kai could see Mr Wu standing just outside, looking up and down the street, waiting–

Mr Wu dropped his cigarette and ground it with the heel of his shoe, the dying smoke expiring in a shower of embers. Kai’s head snapped up. A line of shadowed figures was coming slowly down the abandoned street.

They made no sound. He could not see their faces, could discern nothing about them but their being there, as suddenly as if they had materialised out of nowhere. Kai’s heart beat hard and fast inside his chest, and his palms felt sweaty. Mr Wu, framed by the moon, a small, slight figure, was motionless outside. The dark figures approached slowly, walking a single file. Lightning streaked the sky far overhead, for just a moment, and Kai counted the seconds until the thunder erupted. The storm was still far, but was coming closer. He watched the approaching figures. In that one brief moment of illumination he saw they were cowled.

He would have thought them monks, but no monk he knew wore black. Their robes stole the night and made it their own. He could tell nothing about them, could see no faces or eyes, nothing to tell him who or what they were.

He had noticed one thing, though: they did not come empty-handed.

When the cowled figures came close they halted. Above their heads the sign for Mr Wu’s Celestial Dry Cleaning Emporium stood dark. They halted before Mr Wu and Mr Wu made a stiff bow in their direction, his hands joining together before his chest: a mark of respect. To Kai’s surprise, the monks – if that’s what they were – returned the gesture, their hands rising higher than Mr Wu’s had, showing him the greater respect. Why?

The monks spread out before Mr Wu. Four of them came forward then. They were carrying a heavy-looking crate suspended between them on thick poles of bamboo.

They lowered the crate to the ground. There was another strike of jagged lightning high above, and the thunder came much quicker this time. The storm was approaching fast.

Mr Wu made a jerking movement with his head, aimed at the crate. He said, “Open it.” His voice sounded raw.

Two of the monks brought out wrenches. The others fanned out around them, facing the street. The crate made keening sounds as it was opened, nails groaning, wood splintering. Mr Wu said, “Careful, now.”

There was another flash of lightning and in its light Kai thought he’d seen, for just a moment, another figure moving in the distance, between the trees. Then the crate was fully opened and he turned to look and forgot everything else.

The moonlight hit the figure inside the crate. The two monks with the wrenches moved back. Mr Wu came forward and knelt down beside the broken crate. A scaly, inhuman face – the face of a giant lizard – stared out of the crate. It was made entirely of jade, apart from its eyes, which were giant emeralds. Mr Wu reached into the crate–

The silence was broken, too quickly, the sound foreign and unexpected. Kai had heard it only once before, but he knew it instinctively.

Gunshots.

One of the monks dropped to the ground. His robes seemed to grow even darker. Mr Wu turned his head, startled. He saw Kai and his eyes opened wide. The monks shot out across the street, dark shapes moving without sound, like characters in Kai’s wuxia novel, like Shaolin monks or other kung-fu secret masters, only the sound of gunfire was growing more intense now and it was coming from the forest and the invisible shooters were finding their targets with deadly accuracy.

“Get inside!”

Mr Wu, sheltered by the monks, reached into the crate and pulled out the statue. Kai stared at it, fear momentarily forgotten. It was beautiful – though perhaps that was not quite the right word.

Majestic, perhaps.

Or strange.

A lizard carved in jade, with shining emerald eyes. Sitting cross-legged, like the Buddha. For just a moment he thought he could hear it whispering, a tiny voice in his head, then it was gone and his father was carrying the statue in his arms, back into the relative safety of the Emporium. Kai watched the monks – and now there were people coming out of the jungle, several figures the colour of foliage, and they carried guns. The black-clad monks attacked them. He watched them, mesmerised – they seemed to almost fly through the air, jump off walls and onto the attackers. The fight spread out across the street. One of the green-clad men killed two monks before a third sailed above his head, landing softly behind him and twisting the man’s neck – almost gently, it seemed to Kai – and the man dropped down to the ground, a leaf falling from a tree, the gun tumbling out of his lifeless hands.

A slap shook him out of it. The jade statue was inside the shop and so was Kai’s father, who grabbed him by his shirt and dragged him away from the doorway. He said, “I told you to stay inside.”

Kai said, “I did.” His father shook his head. He said, “You must leave. I didn’t know–”

“What is it?” Kai said. His eyes were on the statue. The statue seemed to be regarding him, perhaps with amusement, perhaps with indifference.

“It’s a–”

Another burst of fire from outside, and it was followed by an explosion of thunder. Rain began to fall outside, great billowing sheets of it, and lightning flashed again and in the light all Kai could see, like a series of frozen tableaux, were the two groups of men fighting, hand-to-hand, in a street full of unmoving figures lying on the ground, the pavement slick and red with blood and rain. He felt sick, for just a moment. Then there was another sound, so soft he almost didn’t hear it, a surprised sound, air escaping a throat, and his father went down on his knees before the jade figure. Kai screamed. His father looked up at him, and blinked. A dark stain was spreading over his crisply ironed shirt. Kai fell down beside him, holding him. His father’s voice was soft, the hiss of escaping air. He said, “Kai…”

Kai said, “No.” He may have said it several times. His father’s lips moved, though no sound came. Then, “Go.”

There was nothing else. Kai shouted but his voice was swallowed by the storm. When he let go his father was lying on the floor. His hand was resting on Kai’s wuxia novel, the cheap yellow pages growing dark with blood.

Kai looked outside and the green-clad figures seemed to be winning, and they were coming closer and closer, and the few remaining monks were now standing before the entrance to the shop, holding them back – but for how long?

Go. The voice had been his father’s. Now it echoed in his mind, and he looked up and for a moment it seemed to him the jade statue was staring at him, no longer amused or indifferent, speaking in his father’s voice. Go.

Kai looked down at his father and knew he was dead. There were gunshots outside and another monk dropped down. Kai screamed again, defiant or afraid he didn’t know, and stood up and with the same motion grabbed the jade statue. It was surprisingly light.

He headed for the back of the shop. Through rustling clothes and the silence where steam had, until recently, been, through the silent presses toward the back door. They might be waiting there too but he didn’t care; his mind was filled with rain and thunder and blood and he burst out of the back door into the narrow alleyway beyond. Then he ran, the statue held in his arms, the rain dripping down his black hair, making his clothes heavy. There were more gunshots behind him but he never looked back. He ran out of the alleyway and down the road toward the trees. He knew the men would come after him. He ran until the forest was there and then he ran through the trees, no longer thinking, the thick canopy holding back the rain, his feet sinking into dead leaves and mud. Running, falling, rising, going deeper and deeper into the forest, until the sounds all died behind him.

Part I

The Murder in the Rue Morgue

One

A Woman With a Gun

There was a crowd of people outside the house on the Rue Morgue, making the place easy enough to spot. Rue Morgue – the unfashionable side of Paris on display, like dirty laundry hanging on a clothesline. Soot-blackened bricks, the smell of rotting rubbish and fresh excrement in the street. Eyes staring out of windows. A neighbourhood where no one wanted to get involved with the law – and yet: a crowd of spectators, eager for a corpse and some entertainment.

The hansom cab had some difficulty navigating the narrow street. The woman inside the cab tapped her long, sharp nails on the windowsill. They were painted a deep shade of black.

There were gendarmes stationed outside the house, doing a bad job of keeping the spectators away.

That was soon going to change.

The cab stopped. The horse on the left raised its head, neighed once, then added its own contribution to the street’s refuse. A couple of urchins turned and giggled, pointing at the fresh, steaming pile.

The door of the cab opened. The woman stepped out.

What did she look like?

Six foot two and ebony-black, a halo of dark hair around her head. Strong cheekbones, pronounced. Her arms were naked and muscled, and there was a thick gold bracelet encircling her left arm. She wore trousers, some sort of black leather, and that might have been shocking, but the first, and then only, thing you noticed about her was the gun.

She wore it in a shoulder holster. A Colt Peacemaker, though there was little that was peaceful about the woman. When the people of the Rue Morgue discussed it, later, they decided it was a coin toss, whether she would shoot you or merely batter you to death with that gun, using it as a bludgeon. They decided it would have depended on her mood.

The crowd moved back a pace, without being asked.

The woman smiled.

You could not see her eyes. They were hidden behind dark shades. She stepped toward the gate of the house. The two gendarmes snapped to attention.

“Milady.”

She barely acknowledged them. She turned, facing the crowd. “Go home,” she said.

She watched the crowd. The crowd, collectively, took another step back. She said, “I’ll count to three,” then smiled. She had very white teeth. “One.”

Her hand was stroking the butt of the gun. She looked momentarily disappointed when the crowd, in something of a hurry, dispersed. Soon the street was quiet, though she could feel the eyes staring from every window.

Well, let them stare.

She turned back and, ignoring the two gendarmes, went through the gate into the house.

The apartment was on the fourth floor. She climbed up the stairs. When she arrived the door was open. A photographer was taking pictures inside, the flash going off like miniature explosions. She went inside. The corpse was on the floor.

“Milady!”

She smiled, without affection.

Flash.

The Gascon was lithe and scarred, and he still carried a sword on his hip as if a sword was any use at all. He said, “We are perfectly capable of solving this murder without interference.”

She arched an eyebrow. It seemed to sum up her opinion of the gendarmes and their investigative abilities. The Gascon said, “Why are you here, Milady?”

She smiled. He took a step back and, perhaps unconsciously, his hand went to the hilt of his sword. She said, “I have no interest in who – or what – killed him.”

“Oh?” Was it relief in his voice – or suspicion?

“The why, though,” she said. “That’s a different matter.”

Flash.

The light was blinding. She said, “Give me the camera.”

The Gascon nodded at the man. The photographer began to protest, then looked at the woman and decided that, perhaps, he should do as he was told after all. She took the camera from him and smashed it against the wall. The photographer cried out. “Get out,” the woman said. The photographer looked at her, helpless, then at his boss. The Gascon was not looking at him. The photographer opened his mouth to voice a protest, caught sight of the woman’s gun, and made a wise decision.

He left. There were just the two of them in the apartment now. “Who owns the place?” she said, though she already knew.

“A Madame L’Espanaye,” the Gascon said. “And her daughter.”

“Where are they now?”

“My men are trying to find them as we speak.”

She said, “Your men.” There was no intonation in her voice, but somehow it made his face turn red. Again he said, “You have no need to be here.”

She said, “Oh?” She still hadn’t looked at the corpse. She moved to the window now, stared out at the night. The window was open, and the ground was four stories below.

“I understand the door was locked from the inside?” she said.

The Gascon said, “Yes. The gendarmes had to break it open.”

“And yet no one could have climbed in through the window,” she said.

He said, “Perhaps…” and there was the faint hint of a smile on his face.

“You have a theory,” she said. It was not a question. And now she turned to him and he wished he could see her eyes. “The man was the lover of the young Mademoiselle L’Espanaye. He was living here with the two women. Perhaps he became affectionate with the older L’Espanaye. Perhaps the younger one didn’t like it. Or it is possible they got together and since blood is thicker, as they say, than water, they decided to get rid of the man who came between them. Either way, once you locate the missing women they will confess – murder solved, case closed. Correct?”

The Gascon had lost the smile. And now the lady nodded with apparent satisfaction. “And you could devise some clever scheme to explain how the murder was committed – perhaps a trained ape had climbed four stories into the locked room, the window left open especially for that purpose? Or, much simpler –” and she was almost done now, close to dismissing him, and he both knew and resented it – “the door was never locked from the inside. What do you think?”

He was standing by the door. She turned her back on him. When she turned again he was standing away from the door. Had there been a key in the lock before? If so it was no longer there. She nodded. “Or perhaps the man committed suicide. Regrettable, when a man takes his own life, but not unheard of.” She tapped her nails against the wall. The Gascon stared at them. She said, “Yes, I like that one best. Leave the women out of it. A suicide, nothing more. Not worth attention – from anyone. I hope you agree?”

“Milady,” he said. The pronounced lines around his eyes were the only outward signs of his displeasure. The woman smiled. “Good,” she said. “Write your report and close the case. Another speedy result for our dedicated police force. Well done.”

He nodded. For just a moment his head turned and he looked at the corpse on the floor, and a small shudder seemed to run down his spine. For just a moment. Then he turned his back on the woman and the corpse and the case and walked away.

Two

The Corpse

Now that she was alone at last she stood still for one long moment. The air in the room was hot and filled with unpleasant scents. She still did not look at the corpse. She glanced around the apartment – cheap furniture, a print on the wall, incongruously, of Queen Victoria – blood. On the walls, on the rickety old sofa, on the floor – the stench of it strong in her nostrils. A drop of blood had hit the lizard queen’s portrait and ran down it like a tear. She went to the window.

Looking down at the Rue Morgue, shadows moved far below, spectators robbed of their moment of excitement. How easy would it be to keep a lid on what had happened here? To the smell of blood, add machine oil, foliage, rot – the smell of a jungle somewhere far away and hot. This last did not belong in this, her city.

Her city. She remembered days running in the alleyways, hunting for scraps, hiding from the urban predators. Had it ever been her city? She was not born there and, later, had not lived there, yet here she was. She glared at the lizard queen’s ruined portrait, deciding the blood added, not detracted, from the painting. She remembered the lizards’ court. Her second, unfortunate husband had often taken her there. His death…

She wouldn’t dwell on it. The barest hint of wind coming through the window, and she realised her face was wet, that the atmosphere in the room had made her sweat. Looking down – was that a shadow moving up the wall, climbing cautiously, some animal well used to shade making its slow and careful way up to this place of death? She watched but could not be sure. She turned away from the window, taking a last deep breath of air fresher, at least, than that inside, and looked at last at the corpse.

That first glance only took a moment, and she turned her head, breathing hard through her nose. She closed her eyes, but the image of the corpse was waiting for her in the darkness behind her eyelids, and she felt the room begin to spin. She opened her eyes and looked again, and this time she did not look away.

A man lay on the floor at her feet.

One side of his head had been caved in. What remained of the face seemed to belong to a man hailing from Asia, though it was hard to tell with certainty. His skin had taken on a waxy aspect. He was lying in a pool of blood, the fingers of one hand – his left – curled into a fist, the other loose, one finger stretched out as if pointing. She half-expected to see a message scrawled in blood, on the floor or the wall, some cryptic riddle to lead her to the man’s killer, but there was none, and it would have made no difference either way since she was not overly concerned with who killed him, but only of what they had taken from the man after his death.

The head wound was ordinary enough. She let her gaze wander further down, past the neck, towards the chest and stomach… yes. She knelt beside him, feeling sick. And now her hands were on him, studying the gash in his corpulent belly. The skin was hairless and the belly-button pronounced, and the man looked pregnant, even in death, as if his stomach had contained a womb and a foetus inside it – though there were none there now.

He had been gutted open, with a long, sharp knife. The flaps of his stomach looked like the torn pages of a book. She took a deep breath and plunged her hand into the corpse, searching, knowing even as she did it that she would find nothing but intestines and blood.

And now there was a sound coming from the open window, a small rustle as of a creature of some sort trying to enter without being noticed, and she turned.

A shadow was perched on the windowsill. She stared at it, her bloodied hand going to the knife strapped to her leg. The shadow on the windowsill moved and gained definition, an impossible apparition that would have frightened the residents of the Rue Morgue to death.

She said, “It’s about time you showed up.” She brought up her knife and suspended it above the corpse, then plunged it in. Perhaps something still remained inside the man. She had to make sure.

When she looked away again the shadow had moved from the window and came crawling towards her. For a moment they were a tableau – corpse, woman above him with bloodied knife, a crawling, enormous cockroach symbolising death approaching or fleeing, she couldn’t decide which. The mechanical cockroach whistled plaintively. The woman said, “That’s hardly an excuse.”

The thing whistled again, and the woman said, “Well, you’re here now, at least. See if you can find anything.”

The cockroach approached, feelers shaking. As it came closer the faint whirring sound of gears could be heard. It was about the size of a small dog. Its feelers moved and another whistling sound came out of its matt-black body, and the woman said, “You’re the forensic automaton, Grimm, so why don’t you tell me?”

The automaton she had called Grimm crawled closer to the body. The woman stood up, cleaning and sheathing her knife, and looked down. Probable cause of death – strike to the head with a blunt instrument. Mutilation inflicted post-mortem – the killer or killers knew what they were looking for and had come away with it.

She watched the little automaton crawl over the corpse. It buried its head in the man’s glistening belly, its legs pushing it deeper into the corpse until it almost disappeared inside, making little whirring noises all the while. She walked back to the window and breathed in the air from the outside: air that carried nothing worse with it than the smell of smoke and dung and rotting rubbish.

Three

A Spark of Electricity

After a while she went through the deceased’s effects. They were few enough. Grimm was still studying the body. Right now its pincers were busy digging deep inside the man’s head, and bits of brain dulled their colour when they emerged. The lady had examined the man’s clothes but had come to no conclusions. The clothes were not new nor were they foreign.

The man’s pockets were almost entirely empty. She found a handful of coins, a packet of loose tobacco, almost empty, and a matchbox to go along with it – no identity card, nothing to suggest who the dead man may have been or where he came from. She looked at the matchbox – the cheap print on the cover advertised a tobacconist in Montmartre. She put it in her pocket.

Grimm was still working on the corpse, emitting little whistles and clicks which she ignored. There was an Edison player on a table by one wall. She approached it but could find no perforated discs. She searched the apartment thoroughly then.

Madame L’Espanaye’s room first – distinguished by more Victoria prints, aerial shots of the Royal Gardens, commemorative china plates, a chipped coronation mug – the woman was obsessed with the royal lizards from across the Channel. Les Lézards. Her mouth made a moue of distaste.

Madame L’Espanaye’s interest in lizards evidently did not extend to her wardrobe, which was full of frilly, lacy, pinkish-dirty, oversized gowns and negligees. That interested the lady a lot more. In the back of the wardrobe she found a box and inside the box a bottle of Scotch whisky, Old Bushmills, expensive and, if she recalled correctly, a lizardine favourite. It was three-quarters empty. Beside it was a roll of bank notes. They looked new. She ran her thumb through them, then put them in her pocket. Curiouser and curiouser.

There was a dresser with a vanity mirror and plenty of rouge and white paint, and she could almost picture the senior L’Espanaye in her mind. She went through the drawers and found a small-calibre gun at the bottom-most one on the left, and it was loaded. The bed was large and unmade, the sheets rumpled. In the small adjacent washroom she found several bottles of pills and grimy walls, and when she ran the tap the water was brackish.

She scanned the bedroom again but found nothing else of interest and moved on to Mademoiselle L’Espanaye’s room. The daughter’s was almost bare, the bed dominating the room, a single chair by the window, candles, many no more than stubs, standing like fat monks around the room, their wicks dead. She tossed the room and found nothing: it was as if no one had lived there and if they had, they’d left nothing behind them.

Conjecture: the two women shared the master bedroom, and the dead man had been using the daughter’s room.

Grimm whistled from the other room, and so she walked over and stared down at the man’s corpse, which looked even worse now than it did before, thanks to Grimm. “Traces of what?” she said.

The automaton spoke in Silbo Gomero, a technical compromise on communication that was also an assurance of confidentiality, since there were not many speakers of the whistling language, in Paris or elsewhere. The language had come from the Canary Islands, adopted by the Spanish who settled there and finally modified by Grimm’s makers using a simplified French vocabulary. Grimm whistled again, and the lady said, “That doesn’t make any sense.”

Grimm whistled, more insistent now, and she said, “What do you mean, watch?”

Instead of an answer the mechanical insect crept closer to the corpse and extended a pincer toward it, gently touching the man’s flesh. The lady watched. A small blue spark of electricity passed between Grimm and the dead man.

The corpse twitched.

The woman watched, her hand going to the butt of her gun without her being consciously aware of doing so. Grimm retreated from the body but it continued to twitch – and now its one remaining eye shot open.

The woman took a step back and her gun was in her hand and pointing at the corpse – she watched a dead foot kick, and the finger that had been pointing at nothing was rising now, impossibly, and the dead man was pointing directly at her, his face twisted in a mask of grotesque agony, accusing her…

The bullet took out the remaining eye and bits of brain exploded over Grimm and the print of the lizard queen. The pointing hand fell down, lifeless again. The body shuddered, once, twice, and finally subsided. The woman reholstered her gun and said, “Get rid of it.”

Grimm began to whistle then, apparently, changed its mind. It approached the corpse again, pincers extended like surgical saws. Together, woman and automaton worked to erase the crime that had taken place there, tonight, and as they worked, dismantling the lifeless body into its separate components, she wondered why it was left the way it had been – were they interrupted, or was the dead man himself a message scribbled into the stones of the Rue Morgue for her to find?

Four

Outside Rue Morgue

When the work was done she left Grimm to dispose of the body parts – the giant insect secreting quicklime, squatting over the man’s dismembered corpse digesting one piece at a time. She looked through the apartment again – there had been no sign of a struggle, and she thought it was a reasonable enough proposition that the two women who resided here had merely been absent – by chance? Or were they paid to make themselves scarce? She thought she’d be able to find them – assuming they were still alive…

A locked-room murder. The apartment was four stories high. Well, Grimm had managed to scale it easily enough. And the window was open… The how of it scarcely interested her. The who, though, had become something of a priority.

She washed her hands in the foul-smelling water in the sink, watching it turn red and pink and disappear in a gurgle down the drain, taking the dead man’s blood with it. She dried her hands thoroughly and returned to the room and was relieved to see Grimm was almost half-way there. When it sensed her it turned, its feelers shaking, and emitted a burst of high-pitched whistles. The lady nodded, then said, “Take the samples to the under-morgue when you’re done.”

She went back to the window, glaring out at the city below. Night was settling in and, if she guessed correctly, the Madame and Mademoiselle L’Espanaye would be hard at work. She pulled out the matchbox she had found on the corpse and looked at it again.

Montmartre.

She put it back abruptly and turned away from the window. Why was the name of the tobacconist familiar? She said, “I’m going for a walk.”

Grimm whistled, a sad lonely sound that followed her as she walked out of the door.

Below, Rue Morgue was deep in shadow, its residents hiding behind their cheap walls. Windows were shuttered, as if excitement had given way, suddenly, to fear.

Good.

She walked alone, and the soft sound of her moving feet was the only break in the silence of the street. She watched the shadows, her hand on the butt of her gun. She was not disturbed.

She decided to walk for a while. She had always liked the city best when it was dark and silent. As a child she–

She turned at the sudden sound and the gun was in her hand and the shadows shifted and then eased back. She smiled, without humour, and walked on.

She thought about the dead man. He had carried something inside his own belly, a foreign object that had somehow been inserted into his flesh, and valuable enough that it had been ripped out of him savagely and carried away. The man had no identity, as yet, and neither did his killers. And as for his cargo…

She thought about Grimm touching the corpse, that little spark of electricity that had set the dead man rising. She had to conclude that, though he was human on the outside, his inside may have been a different matter. Well, it was of little concern right now. No doubt the doctor would be engrossed by Grimm’s samples, down in the under-morgue…

She passed out of Rue Morgue, breathing a sigh of relief, though the entire neighbourhood was the same, dark and dank and dismal. She headed for the Seine, finding her way with ease through the narrow, twisting streets. The old city morgue used to sit at the end of that street, she remembered, lending the road its name. Thoughts of the corpse niggled at her. She had seen plenty of bodies but nothing like the one Grimm was busy erasing from existence.

After a while the streets became wider and more prosperous. She found an open café and went inside, into the gloom of candles and smoke. She ordered a coffee and sat down by the window and glared at the night.

The door of the café banged open, then shut, and a shadow slipped into the seat opposite her. She raised her eyes and stared at the smiling Gascon.

“Milady,” he said. “What a pleasant surprise.”

She glared at him. The Gascon signalled to the waiter, mouthed, “Coffee.”

Ignoring her.

“You followed me,” she said.

“Surely a coincidence,” he said, and now his smile hardened. “Of all the places–”

“What do you want?”

The Gascon shrugged. And now the smile melted away, having never reached his eyes. “That murder is mine,” he said.

“What murder?” she said, and was pleased to see the flicker of anger that passed over his face.

“You wouldn’t,” he said.

She sipped her coffee. The hot liquid revived her. She stared at the man evenly, waiting him out. He looked away first.

“The Republic has law,” the Gascon said at last. “You can’t cover up–”

“Can’t?” she said. And now she stood up, dismissing him. “Stay out of my way,” she advised. “And forget about the Rue Morgue. There is nothing there for you now.”

He looked up at her. She examined him, feeling a vague sense of unease. Why was the Gascon still pursuing the case?

“I can help you,” he said. His voice was soft. She smiled, showing teeth, and walked away without answering him, her back to him all the answer she needed to give, and the door banged shut behind her.

Five

Across the River

She could have taken a coach or one of the new baruch-landaus but instead she walked, not feeling an urgency any more, but wondering what it was that had been surgically inserted into the dead man’s belly. It was not a case of murder, she thought, but theft. She found the Seine and followed it for a while, watching the ruined Notre Dame cathedral growing larger as she approached, a wan yellow moon rising above it. Lizard boys hung around the broken-down structure at all hours: hair shaped into ridges over otherwise bald domes, skin tattooed into lizard stripes, tongues forked where they had paid some back-room surgeon to split them open. Dangerous, yes, but predictable.

She crossed the river, looking down at the Seine snaking its way through the city, a lone barge still floating down it at this late hour, carrying pails of garbage, and she thought – there were a hundred different ways to disappear forever in this city.

She walked away from the river, into the maze of never-ending streets, her feet sure on the ground, knowing their way, the ground like taut skin stretched over the body of a giant lizard. She thought the dead man must have come into the city very quietly, but not quietly enough – had slipped in and found the apartment in the Rue Morgue, thinking it was safe – he must have waited, must have made contact with person or persons still unknown, and waited to conclude the transaction – for she was sure that’s what it was – but had somehow faltered. Or not. Perhaps he knew all along how he would end up, a gutted fish in a Parisian market where everything was for sale.

She walked for a long time, her long legs carrying her easily, swiftly, along the ancient narrow streets. She knew them well. As a kid she had run through them, had lain in wait for the apple cart owner to turn away for just one crucial moment – for a dark shadow of a girl to swoop and make a grab and run away, laughing. She had looked through rubbish piles for clothes and food, and hid in the abandoned places, the tumbledown houses where others roamed, the animals in human guise who preyed on those who had the least of all… a far cry from the home she could no longer remember, the place where she’d been born, so far away, where the sun always shone, where her mother had come from, the same mother who had died so quickly here, in this new land of white men and gleaming machines. She had first killed in a place just like this, a dark alley where a man was bent over a child – a boy who was a friend, as much as the other small humans on the street could be called that – and she had snuck behind the man and cut his throat with her knife, feeling nothing but a savage satisfaction, and the boy – he was still alive – had staggered away from under the corpse and down the street, clothes drenched in blood, some of it his own. She never saw him again, and there had been other predators, other animals on the streets of this most glorious Paris, city of equality, fraternity and liberty, this city of the Quiet Revolution.

The streets gradually became brighter, lamps alight and places of business still open: night business, for she was approaching Pigalle. There were people on the street, women leaning at corners, two men fighting in an alleyway, drunks spilling out of a nearby tavern, the sound of music and shouting and dancing from a building nearby, a brasserie serving buckets of mussels with bread for late diners, glasses of beer – faces leering at her until they saw the gun and turned away, eyes suddenly, carefully empty. She saw a man’s pocket being picked by a small child and two gendarmes watching without comment. The man never noticed but the gendarmes did and when the child tried to run they were waiting for him, counting the money, taking out their share. This was her world, had been her world, and she still felt more comfortable here than she ever had at the lizardine court or the embassy balls – though that was merely a different kind of throat-cutting and pick-pocketing, done on a different scale.

The little boy ran off, and the two gendarmes disappeared through the doors of a bar. She walked on. Closer to Montmartre now, and the streets grew quieter, the ruined church on the hill above casting down a faint eerie glow. She walked a short way up to the small square where a couple of restaurants were closing, and into the all-night tobacconist’s that only recently had sold a box of matches to a dead man.

Six

The Immaculate Mr Thumb

Thumb’s Tobacco was well lit and empty. Behind the counter were orderly rows of the tobacconist’s merchandise. Hanging on the walls, startling her for a moment, were posters advertising The PT Barnum Circus – The Greatest Show on Earth! A tall black woman, muscled and scantily clothed, holding a pair of guns, was featured on one. She looked at it for a long moment and bit her lip. The Ferocious Dahomey Amazon! screamed the notice above her head. She smiled at last, and shook her head, and looked away. Then she looked over the counter and a pair of eyes stared back up at her.

The eyes rose to meet hers – and now she knew why the name had sounded familiar, as the eyes blinked recognition and a wide grin suddenly split the small face they came with.

“You!”

She nodded, unable not to return the grin as the small man behind the counter straightened up, climbing onto a stool so that he stood with his upper body above the polished wooden top. “Cleo–” he said, and she shook her head, No. “It’s De Winter now.”

“I haven’t seen you since–”

“It’s good to see you, too, Tom,” she said.

The Vespuccian man was dressed immaculately in a child-sized suit, a pocket watch hanging on a chain from his pocket. “Since you left the circus,” he said.

“It’s been a while.”

“I have your publicity poster,” the small man said proudly, gesturing at the wall.

“I saw,” she said, not following the gesture. Looking at him.

“Last I heard you were in England,” he said. He rubbed his thumb and finger together. “Married to some lord.”

She said, “He died.”

The grin grew larger. “They tend to do that, don’t they?”

She let it pass. For now. She said, “Last I heard you were in England.”

He shrugged. “Had to leave in a bit of a hurry, didn’t I.”

“Why doesn’t that surprise me?”

The small man shrugged again.

“Still fomenting revolution?”

“Nah, mate,” Tom Thumb said, “I’m legit now. Out of the revolutionary business. Minding my own business, for once, and liking it that way.”

“The quiet life,” she said.

He nodded, watching her carefully, no longer smiling now.

She said, “I find it hard to believe.”

Tom Thumb shrugged. Believe what you want, the shrug seemed to say. See if I care. And now she smiled, and the little man shrank a little from it.

She took out the box of matches from her pocket, played with it. Tom Thumb watched her fingers. “You smoking now?” he said. “You never used to.”

She flipped the box over, not answering him. Printed on the cover was Thumb’s Tobacco, Montmartre. The painting showed the front of the shop, a little figure just visible behind the glass. She threw it across the counter at him and he flinched back but caught it.

“One of yours?” she said.

He looked at it, put it down on the counter. “Got my name on it, hasn’t it?” he said.

“It does, at that,” she said.

“So?”

He was watching her warily now, caged but not yet knowing why. Or maybe he did… maybe he’d been expecting her, or someone like her, to come eventually to his shop.

So… “Popular shop?” she said, looking around her at the empty space.

“Doing OK,” he said, using the Vespuccian expression. It almost made her smile – she hadn’t heard it in a while.

“That’s a nice suit,” she said instead.

“Thank you.”

“Must be expensive.”

“Oh, you know…” he said.

“And that watch. Gold?”

“This old thing? Nah. Just looks like it.”

“It certainly does. Looks new, too.”

Tom Thumb stared at her, expressionless. “You a copper now?”

It was said less as a question – more an accusation.

“We’ve all got to make a living,” she said. “Don’t we, Tom?”

“I’m making a living,” he said. “I sell tobacco.”

“So I see.”

“Well, it was nice seeing you,” he said, “Milady. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I have a lot of work to–”

She reached across the counter and picked him up. He said, “Wha–”

“I’ll dismiss you,” she said. “When I’m done with you. OK, Tom?”

She dropped him. He glared at her, smoothed his jacket where she had grabbed him. Suddenly he grinned again. “Come see the ferocious Dahomey Amazon!” he said. “Remember? I used to love your act. Got your publicity poster right there–”

“I know, Tom. I saw it.”

“Yes, well, we’re old friends, you and I, aren’t we? There’s no need to get rough.”

“I hope so, Tom.”

She waited him out. He stood, watching her – she could see him thinking. She didn’t hurry him. At last he said, “Sit down, I’ll make us a brew.”

Sit down, I’ll make us a brew. As if they were back at the circus, and the last show had finished – everyone winding down, but not yet ready to let go – the rush still there, the shouts of the crowds, the smell of sweat, and smoke from the torches, roasting peanuts and piss from the animal enclave… sawdust. Sometimes she really missed the smell of fresh sawdust.

It always became less and less fresh as the evening progressed.

She said, “OK.”

Seven

Imports & Exports

Tom Thumb made coffee. He put a coffee set down on the counter between them – sugar cubes, small jug of milk, a couple of pastries, cups and saucers and spoons.

She took hers black and drank it through a sugar cube. “It’s not bad,” she said.

“It’s from–” he said, and then he hesitated.

She said, “You selling coffee now?”

“Amongst other things.”

“What sort of things?”

“Cleo–” he said, then checked himself, almost saying her full name, the way she was billed back in the show. “Fine, fine! Milady, then.”

She waited.He said, “Is this going any further, or is this between us?”

She thought about it, said, “It depends.”

“On what?”

On a corpse that was no longer there… She said, “I don’t care what you do. I’m just trying to find something that’s missing.”

“What sort of something?”

“I’m not sure yet.”

He shrugged, letting it go. “Fine,” he said. “What do you want to know?”

“I want to know who bought that box of matches from you.”

Tom Thumb looked exasperated. “How the hell should

I know?”

“He was Asian.”

She saw him noticing the was. And now his eyes narrowed, and his hand played with the pocket watch, releasing and closing the lid, working it.

“An Asian man who needed a place to hide out in…” she said, “Where did you say your coffee comes from again?”

“I didn’t.”

“But you were going to.”

“Was I?”

Open, shut, open, shut. She took another sip of her coffee. “Leave that alone,” she said.

“Lots of Asians in Paris,” Tomb Thumb said at last. “Indochina. Siam. Doing business. So what?”

Making a connection, and she threw him a line: “You selling opium?”

… and he bit. Tom Thumb shrugged. “A little. Not illegal, is it?”

“No,” she said. “But this isn’t a smoking den, so what, you deal bulk?”

He didn’t answer.

“Got a contact over there? Sends you stuff over?”

No reply.

“Coffee, for instance?”

“It’s good coffee,” Tom Thumb said. “Good opium, too.”

“What else does he send you?”

Nothing from Tom, staring out through the window into the night.

“People, sometimes?”

Tom, still staring out at the night. Thinking. How much could he tell her? She knew that look.

“People who need somewhere to hide, for a little while?”

Tom turned to her. No smile, eyes calm like grey skies. “Is Yong Li dead?”

And now she had a name. “Yes.”

Tom said, “Damn.”

I have a little shipping business (Tom Thumb said). Import/export, with this guy in Indochina on the other end of it. I buy coffee, tobacco, now and then opium for those who like that sort of thing – all legit. So maybe I don’t pay customs every time, you know? And maybe sometimes, just sometimes, I ship some stuff East.

What stuff? You know. Stuff.

You don’t know?

But you want to.

It’s nothing serious, Cl – Milady. Milady de Winter, huh? Seriously? Think I met Lord de Winter once, back when I was still living across the Channel. Whatever happened to–

Fine. Yes. Arms. Sometimes. And literature.

What do you mean what literature? How should I know?

I’m more of a drop point, now that you press me on it. Don’t think I’m the only one working for this guy. So sometimes they drop off little packets for me – mostly paper. I don’t know what’s in them though.

Did I look? No.

Fine, maybe I did a couple of times. Didn’t make much sense, though. Technical stuff. Like, you know those Babbage engines? That’s what some of it looked like. Technical specifications. Once this mechanical beggar came into the shop, a proper derelict, could barely move, one of those old people-shaped ones, moving one leg after another, you can hear the motors inside they were so loud, doesn’t say a thing but drops off this box – I open it, it’s got an arm inside.

No, a metal arm. Real artwork. Only, I open the box, this arm reaches out, tries to strangle me. After that I didn’t look again.

Yes. I’m getting to that. So, we do business, you know, mostly legit, a little bit of it under the counter – don’t you dare make a joke – only sometimes there’s people need to get from here to Indochina don’t want to be going through the usual channels. I don’t ask questions. Usually I know to expect them. Then off they go with the next shipment.

Got his own ship, ships, I don’t know.

Sometimes he sends people over. No papers, half of them don’t speak the language. I mean, any language. Don’t know what they want. If they need it I arrange a safe house, somewhere to put them, lie low for a while. If not then poof – they disappear into the city, I never see them again.

Where the safe house is? You don’t think I’m going to tell you, do you?

How did you know?

Oh.

So that’s where you found him. Poor bastard.

He came in about a month ago. Nervous little guy, fat belly, gave him lots of problems, cramps, I don’t know. He kept holding it, almost looked pregnant. I put him up for a couple of nights. Nice guy. Taught me this drinking game–

I don’t know where he was from. Don’t know what he was doing here. I don’t ask questions. A couple of days later L’Espanaye tells me the place is free, I send him over.

The mother, yes. She’s the one I’ve been dealing with. Wouldn’t mind dealing with the daughter though, if you know what I mean.

Right. Sorry.

No, never saw him again. Didn’t think I’d hear about him again either, until you walked through my door.

The poor bastard.

He was a nice guy.

Eight

Tattoos

She finished her coffee. Tom Thumb lit a cigar. She watched him – trimming it first, then using the matchbox that came from a dead man’s pocket. Tom blew out smoke. She said, “Do you have any idea what he was carrying?”

“Ask no questions,” Tom Thumb said, “hear no lies. That’s my policy.”

He knew more than he was telling her. She was sure of that much, at least. But Tom Thumb wasn’t going anywhere. He’d been going nowhere for a long time. She said, “And the name of the man you deal with? The one in Indochina?”

Tom shrugged. “Never asked his name.”

She let it pass. “What does he do, exactly? Beyond selling you coffee?”

“No idea.”

But she had an idea.

“You’ve always been a revolutionary,” she said. “What were you doing in England, Tom?”

“Minding my own business,” the little man said. He blew smoke towards her and she smiled and reached over and pulled the cigar from his mouth and put it out on his hand.

Tom screamed.