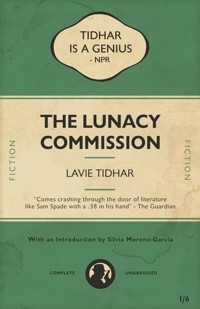

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc.

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

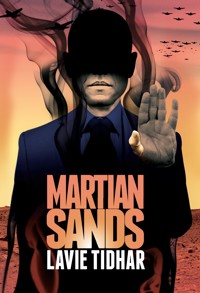

1941: an hour before the attack on Pearl Harbour, a man from the future materialises in President Roosevelt's office. His offer of military aid may cut the War and its pending atrocities short, and alter the course of the future... The future: welcome to Mars, where the lives of three ordinary people become entwined in one dingy smokesbar the moment an assassin opens fire. The target: the mysterious Bill Glimmung. But is Glimmung even real? The truth might just be found in the remote FDR Mountains, an empty place, apparently of no significance, but where digital intelligences may be about to bring to fruition a long-held dream of the stars... Mixing mystery and science fiction, the Holocaust and the Mars of both Edgar Rice Burroughs and Philip K. Dick, Martian Sands is a story of both the past and future, of hope, and love, and of finding meaning—no matter where—or when—you are.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 288

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Copyright © 2013 by Lavie Tidhar

All rights reserved.

The right of Lavie Tidhar to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Originally published in printed book form by PS Publishing Ltd in 2013. This electronic version published in May 2013 by Jabberwocky Literary Agency, Inc., in conjuction with Zeno Agency LTD.

ISBN 978-1-625670-61-8

This book is a work of ficiton. Names, characters, places and incidents either are products of the author's imagination or are used fictiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Cover design by Pedro Marques © 2013

For my grandparents—the ones I knew, and the ones I didn’t

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Part One: Life on Mars

Part Two: The War of the Worlds

Part Three: The Silver Locusts

About the Author

Lives come and go like seagulls. On cooling sands the grey sea comes to rest. The eye stalks of sea-weed peer over the crest

Of dying hulls.

Ships dipped in water. Sails crusted in frost.

Grandfather’s face rises over the surf

A mast-head blinded by salt.

Now the secret black water drains on the sand—

Lives come swiftly over the breakers,

Dip once, and are gone.

— L.T., The Breakers

Part One: Life on Mars

ZERO

The President of the United States was sitting alone in the Oval Office when a man he had never seen before came through a door the President had, likewise, never seen before, stopped before the President’s desk and said, ‘I have a proposition for you.’

The man was of medium build, with short brown hair and soft brown eyes, a good ssuit and an open, almost earnest expression. The thumb on his left hand was a golden prosthetic. He said, ‘My name’s Glimmung. Bill Glimmung. But you can call me Bill.’

The President looked at him without expression, then reached for a cigarette and lit it. On the desk before him an ashtray was overflowing with cigarette stubs. In front of the President were papers, the most recent of them stamped with yesterday’s date: the sixth of December, nineteen forty-one. ‘How did you get in here, Bill?’

The man—this Bill Glimmung—nodded as if approving of the President’s question. He pointed. ‘Through that door.’

‘That door wasn’t there a moment ago,’ the President said.

‘It’s from the future,’ Bill Glimmung said. ‘And, naturally, so am I.’

The President was tired. He had been chain-smoking, poring over military intelligence briefs coming in from Europe and the Pacific. He was worried about the Nazi expansion, about possible Japanese involvement in the war, about convincing his own people that they should become involved. ‘It’s good to know there will be a future,’ the President said dryly, and Bill Glimmung laughed. ‘Possibly a very good future,’ he said, ‘if you take me up on my offer.’

The President looked him over. There was the door, there was the man—and there was something terribly ordinary about both. And therefore, the President thought, also remarkably odd. He doubted the man was an assassin (had he been, the President would no doubt be dead by now) but he also knew—they both did—that the President was, if only for the moment, a captive audience.

‘Tell me about it,’ Franklin Delano Roosevelt said, and gestured with the hand holding the cigarette. A little ash fell, scattering over the papers. The President brushed it away.

Bill Glimmung nodded again, looking satisfied. ‘I represent the State of Israel,’ he said.

‘There isn’t–’ the President said, then stopped. Glimmung nodded. ‘That’s right,’ he said. ‘It doesn’t exist yet. It will be established in nineteen forty-eight—three years after the end of the war, incidentally—and only after more than six million Jews die under the Germans in specially-constructed death camps.’

His tone was mild, matter of fact. ‘Six million Jews—men, women, children—packed like cattle into trains and sent to the Vernichtungslagers. The Extermination Camps. There to be killed by Zyklon-B gas, and their bodies burned in crematoriums. Six million, Mr. President. The greatest coordinated, scientific, mass extermination of people the world has ever seen. My people—my government—would very much like to see that changed.’

The President nodded, once. He reached for a cigarette, then realised he already had one lit. He raised his head and looked at the stranger. ‘What is your proposition?’ he said. Whether he was reeling inside, whether he believed Bill Glimmung, it did not show on his face. His tone was practical, emotionless—matching Glimmung’s.

‘You know,’ Bill Glimmung said, ‘you Americans are a strange breed. Take today, for instance. Today, Mr. President, is a bad day for you. Don’t worry,’ he said, waving his hand, ‘I’ll show it to you soon. It’s not yet time.’

‘Time for what?’ the President said, but Bill Glimmung seemed not to hear.

‘You know what you’re going to call today, this date?’ he said. ‘A date which will live in infamy forever. Whereas, in fact, it’s tomorrow that should be called that. Do you know why?’

The President stared at him. He stubbed out his cigarette, a little forcefully. He didn’t answer.

‘Tomorrow,’ Bill Glimmung said, unperturbed, ‘the Nazis will open their first death camp. Chelmno, near Lodz. That’s in Poland,’ he added helpfully.

‘I know,’ the President said. They stared at each other. Bill Glimmung turned away first. ‘December eighth, nineteen forty-one,’ he said quietly, almost as if speaking to himself. ‘Chelmno. To be followed soon after by Majdanek, Sobibor, Treblinka, Belzec and, of course, Auschwitz. Many members of my family died in Auschwitz, Mr. President.’

‘I’m sorry to hear that,’ the President said. Bill Glimmung turned to him, a thin smile on his face. ‘Don’t be sorry, Mr. President,’ he said. ‘You can help change that.’

‘What happens today?’ the President said.

Again, Bill Glimmung seemed not to hear. ‘A date which would live in infamy, forever,’ he said. ‘And you could change that. Once you join the war–’

‘I have been doing everything in my power to fight the Nazis,’ the President said, interrupting him. ‘Short of joining the war. But I can’t go to war without the consent of my people.’

‘Oh, I wouldn’t worry about that,’ Bill Glimmung said. His thumb, that strange, gold prosthetic, flashed as his hand moved. ‘Today is the day America gets dragged, kicking and screaming, into this world war. It’s why we picked today to contact you. We want to help you. We don’t just want you to win—which you would do regardless—but we want you to win quickly. And, of course, we want you to stop the slaughter of the Jews. Which is why you will be bombing Chelmno tomorrow.’

‘Okay,’ the President said. He reached for, and lit, another cigarette. Bill Glimmung’s face bore a disapproving look, and the President allowed the smoke coming out of his nostrils to waft toward the other man. ‘I take it you don’t smoke, in the future?’

‘No.’

‘A pity.’

Bill Glimmung shrugged and remained silent.

‘Okay,’ the President said again. And, ‘What is your proposition?’

‘Military aid,’ Bill Glimmung said. ‘We will provide you with late twentieth-century equipment, as per the following–’ and he took out a piece of paper from his suit’s breast pocket and put it down before the President.

‘Small arms: Uzi, Negev and Dror machine-guns; Desert Eagle and Barak handguns; Galil, Tavor and Magal assault rifles. Also some sniper rifles. Also ammo. We can only provide a small amount of these, to be used exclusively in the European campaign, specifically for the liberation of the Jewish ghettos and camps. We expect you will train a special commando unit for this purpose. We will provide instructors.’

The paper, the President saw, was very strange. There were images on it, showing him the weapons as Bill Glimmung listed them, lines and lines of technical specifications running underneath, and the images kept changing, the text with them, as if the paper was a sort of screen, and somewhere there was an unseen projector.

‘We can also provide you with a limited number of Merkava tanks—fifty kilometres per hour; a hundred and five millimeter cannon, mortar, and three machine guns, per unit—also to be used in the European campaign. Basically, what you do in the Pacific is your prerogative. Our interest lies with the Germans.’

‘Naturally,’ the President said.

‘Yes.’

‘These look…impressive.’

‘Thank you. We will also provide you with several Kfir all-weather, multi-role combat aircraft, jet-powered, seven hundred and seventy kilometres range, max speed of over two thousand kilometres per hour, and a battery of Jericho I ballistic missiles, with a five hundred kilometres range.’

On the sheet of paper, images flickered and changed. The President watched arrays of gleaming weapons being fired, a variety of targets being demolished.

‘Finally,’ Bill Glimmung said, ‘and most importantly, we will provide you with intelligence. We can tell you where and when to strike. We can tell you what forces the enemy is moving, and where. In other words, Mr. President— we can tell you how to win this war.’

‘And in exchange?’ the President said.

‘You will make the liberation of the Jews of Europe your foremost priority. You will also… encourage the British to make available to the Jews a suitable land for settlement.’

‘I…see,’ the President said. He tapped ash carefully and said, ‘Naturally, I will need to consult with my–’

‘No,’ Bill Glimmung said. ‘Believe me, you won’t. Not after today. And, naturally, Mr. President-’ and he smiled that thin, slightly mocking smile again ‘-this will need to remain a secret, known only by the few. Geheimnis, if you like.’ And he laughed, as if at a private joke.

The President blew out smoke in silence, and watched him.

‘Let me show you something,’ Bill Glimmung said. He took a second, small rectangular piece of paper from his breast pocket and proceeded to unfold it, until it was the size of a sheet. He went to the Oval Office’s wall and hung the sheet on it. It stuck to the wall easily. Bill Glimmung pressed his gold thumb onto the thin material, and images flickered into life.

At first, there was not much to see. A dark sky, and clouds. Then…

‘These are Japanese bombers,’ Bill Glimmung said. The images shifted and changed, showed ocean, then land. ‘You recognise the harbour?’

The President stared at the screen. ‘Pearl Harbor?’ he said.

On the screen, an explosion bloomed in the darkness. And another. And another.

The President swore and reached for his phone.

‘Don’t,’ Bill Glimmung said. He shrugged. ‘It’s too late for you to do anything, now. This will be over in ninety minutes.’

‘Damn you!’ Franklin Delano Roosevelt said.

‘Six million,’ Bill Glimmung said, so softly the President had to strain to hear him. ‘This war is happening now, Mr. President! And your country remains content, remains on the sidelines, unwilling to become involved. Tomorrow, the first death camp opens. After today, you will finally be part of this war. I am offering to help you end this quickly. No massive loss of American soldiers’ lives, no dead Jews in the Vernichtungslagers. Make your choice, and do it quickly. I—we—will not make this offer twice.’

‘How do I know I can trust you?’

‘You don’t. All you have to do is think what would happen if we negotiated with the Japanese instead. We’re reasonably sure that, with our aid, they’d be able to take on the Germans. Of course, when we show them what you do to them at the end of the war…’

The President stared at the wall, where Pearl Harbor was burning. ‘Very well,’ he said. ‘We will accept your aid, and your terms. The liberation and resettlement of the Jews. Is that it?’

‘Hmmm?’ Bill Glimmung turned away from the images on the screen. That thin smile had left his face and he said, almost apologetically it seemed to the President, ‘There is one other thing–’

ONE

In his small apartment in the Martian Sands co-op, Josh Chaplin woke up to the sound of his alarm-clock berating him.

‘Wake up! Wake up! It’s time to go to work!’ the alarm-clock said. ‘Time and tide wait for no man! A penny in time saves nine! An army marches on its–’

Josh’s hand landed with some force on the alarm-clock and he tried to strangle it. The alarm-clock, its eyes bulging, tried to bite him. ‘I’m awake!’ Josh said.

The alarm-clock subsided in a huff. ‘I must remind you,’ it said, a little stiffly, ‘that the time now is seven twenty-one. Breakfast is being prepared for you in the kitchen. You have twenty-four minutes left to eat, shower and catch the seven-forty tram to work.’

‘I can’t afford a shower,’ Josh said. Why am I telling you this, he thought. Damn clock. He would have thrown the useless thing away years ago, but…

‘If your grandfather could see you now,’ the clock said, and clucked.

Josh groaned. He rose from the bed and took the two steps necessary to reach the small cubicle that was his shower, toilet and sink, not bothering to slide the transparent plastic door shut. He shaved quickly, cutting himself, then brushed his teeth despondently. He stared at himself in the small mirror: black curly hair, receding now, a high forehead, deep-set eyes with dark rings around them. I look like my grandfather, he thought. I look like I’m on my way out already.

He left the sink and crossed the invisible line that separated the bedroom part of the apartment from the kitchen. A plate was already waiting for him on the table, two slices of toast and a mug of coffee—what passed for coffee, anyway, he thought. He took a sip, burning his lower lip. It wasn’t too bad, he decided—I can’t remember what coffee really tastes like anymore. He chewed on the toast. The alarm clock burped behind him.

‘The time now is seven twenty-nine,’ the clock said. ‘You have eleven minutes to–’

‘Yes, I know,’ Josh said. ‘Please shut up.’

He finished his toast in blessed silence. When he was finished he deposited the plate and cup in the kitchen sink.

‘Thank you!’ the sink said without a hint of irony. ‘I shall look forward to washing these utensils until they sparkle!’

‘Appreciate it,’ Josh said. He glanced back at the clock, who was strangely quiet. ‘See?’ Josh said. ‘Why can’t you be more like the sink?’

‘The sink is provided to you as part of the Co-Op Experience,’ the clock said, and blinked. ‘I, on the other hand, am a personal possession, without the overlaying happy-clappy programming of the rest of the apartment. I am one of a kind. Hand-made in Zurich by the best clock-making firm in the world, Schultz and Co. Your grandfather paid one thousand, two hundred and fifty Euros for me which, translated into the current exchange rate for the Martian Shekel, comes to–’

Josh raised his hand. ‘I don’t care,’ he said.

‘I am an antique,’ the clock said.

‘That’s just another word for old rubbish,’ Josh said, and was gratified to see the clock blink again.

That’s it, Josh decided. I have to do better at the job from now on. I need to sell over-quota or I’m never going to afford a shower. And if I make a big sale—and it’s possible, Rajani’s had three just last week—then I’ll get the clock fixed. After all, it wasn’t the clock’s fault it was stuck on nag mode. It was just old.

‘How would you like to be fixed?’ Josh said. ‘There’s a shop in town I think fixes old–’

He fell silent. The clock stared at him, mute for once, a hurt look in its eyes.

‘I better go,’ Josh said, defeated. I can’t afford to fix you anyway, he thought. No one ever sells over-quota. They set the quota so you can’t even reach it most of the time. Only Rajani… A sudden, unexpected hatred of the small Indian man filled him. How does he do it, he thought. I’m lucky to make three sales a day, and he does almost fifteen, it’s not right. It’s like the system is fixed in his favour. It’s…

Resignation took over. I guess I’m just not very good at selling, Josh thought. The truth is I hate it. I have to try and find a new job. That’s it! he thought. I’ll look for a new job today. Seriously this time. There must be something else I can do, anything else—isn’t there?

Tomorrow, he thought. I’ll start tomorrow.

‘The time now is seven thirty-four,’ the alarm-clock said, jarring him back from his thoughts. It sounded gleeful. ‘You have six minutes left to get to the tram stop.’

Josh swore. Then he reached for his shoes and slipped them on, reached for his bag and slung it over his shoulder, and finally, as he had done every day since he was a child, went up to the bedside table and said, ‘Goodbye, clock.’

‘Goodbye, Josh,’ the clock said. ‘Have a good day.’

‘I’ll try,’ Josh promised.

He turned at the door. The clock was waving goodbye. Josh waved back, feeling again the way he did when he was a school kid, and left the apartment.

What does the clock do all day in the apartment, he wondered. Does he talk to the sink? And if so, what do they talk about? I should try to find out, he thought. Scatter-shoot pinhole cameras throughout the apartment. But of course, the clock would know.

He walked down the long corridor, passing rows and rows of identical doors. At last he reached the lift, but it seemed stuck on the second floor, far below.

I don’t have time for this, he thought. I’m going to miss the tram.

He began to run. Ahead of him, the quick-drop exit, at the end of the corridor. Thankfully, no one was using it. They’re probably all asleep, still, he thought, resenting his neighbours. He wouldn’t be awake either, now, but for getting the dead shift again. No wonder I can’t sell anything, he thought. No one wants to buy anything early in the morning. I’ll have to talk to Feintuch again, try to change shifts.

He pressed the button for the quick-drop and the doors opened with a soft whoosh. He eased into the harness and clutched the cable in both hands, half-closing his eyes.

The doors closed.

He dropped. Fast.

Above his head, the parachute billowed, momentarily sending his falling body upwards. Then he glided the rest of the way to the ground, waited as the harness unclasped itself from his body, and stepped through the opening doors in one practiced motion.

The doors closed behind him. The time flashed in the lower left corner of his field of vision. Seven thirty-seven.

He had three minutes left.

Cursing again, he ran out of the co-op building onto the street outside. The sun shone into his eyes through the great transparent dome. An inter-city car zipped past him, the driver honking. It looked like a little red beetle, Josh thought, envious. If only he could afford a car… He wondered who the driver was, that he could afford one. It was definitely a Shenzhou, one from the new range, he thought. There couldn’t have been more than a thousand of them on the entire planet, a lot less if you didn’t count the Israelis. Rich bastards.

Two minutes, it flashed at the corner of his eye. He turned right, almost ran into the lame metal beggar, the robotnik who always sat outside the co-op entrance, cursed, and continued running. He could see the tram coming towards him, slowing down at the stop…

His lungs burned and he thought, Every bloody day. I have to get fit.

He reached the stop as the doors were closing, and managed to squeeze inside just in time. He took in a deep gulp of air and reached for the strap above him. The tram moved, jolting him. He scanned the carriage. Typical. There was nowhere to sit.

‘You’re lucky you made it,’ the man next to him said. He was short, bald, with a deep-black skin and an implant, an honest-to-God old-fashioned bloody implant behind his left ear, which for some reason really offended Josh. ‘Doesn’t matter that you delayed everyone on the tram.’

‘Look, buddy,’ Josh said, ‘this is public transport, not your own goddamned RLV. So spare me the–’

His attention wandered mid-sentence. In the street outside, walking along as if she were an ordinary person, walking her dog in fact, who was a little collie puppy, bright-eyed, hardy, a real Martian dog—was Sivan Shoshanim.

‘My God,’ Josh said, forgetting the tram, the running, and the man beside him, ‘it’s her.’

The man beside him had apparently also turned to look. ‘Her who?’ he said, in a tone that suggested he was not finished with the argument the way Josh seemed to be.

‘Her,’ Josh said, pointing. She was walking along the road, early morning shopping, keeping up without effort with the slow-moving tram. She was glorious, gorgeous, dazzling, stunning—sublime. ‘Sivan.’

‘Sivan Shoshanim? Where?’ said an older lady with a seat nearby, and turned to look, her eyes brightening.

‘I don’t see her,’ the man beside Josh said. ‘What would she be doing here, anyway? It’s not like she even knows Lo-Rent exists.’

‘I see her!’ the older lady said. She almost clapped her hands in glee. ‘Imagine that!’

‘Hold on,’ the man said. He sub-vocalized to himself. ‘Ah, I can see her now,’ he said. ‘I run a block against ads,’ he explained, smiling slightly. Mocking Josh.

‘An ad?’ Josh said hollowly. The tram turned and bent on its familiar route and began to gather speed. Sivan Shoshanim, Josh now saw, matched the tram’s journey exactly, was still directly before his eyes, still walking at a regular pace.

‘Well, you didn’t really think she would be here, did you? Just happened to come down to our level, taken the bloody dog out for a walk, did you? How dumb are you?’

‘Hey!’ Josh said, flushing. I should have known, he realised. She was just a damned advert. Keyed into his node through the tram’s hub, no doubt—that was only one of the minor drawbacks of using public transport, the subliminal ads, and the way they sometimes messed with your visuals. He felt as though he’d been gutted, but still he couldn’t take his eyes off her. She looked so real.

Then, as he watched, Sivan Shoshanim turned her head—and looked directly at him. He stared into her eyes, those beautiful, violet eyes he knew so well—and she smiled at him.

Josh put his hands against the window. He was captivated. He smiled back.

Then the tram had turned one last time and came to a halt at the next stop, and the doors opened and people pressed against him and pushed to get out, and then to get on, and by the time he looked back she was gone.

By the time he got off at his stop, on the other side of the city, he was sweaty, and thoroughly miserable. He had not been able to grab a seat throughout the journey. It was now eight twenty-six. He had been on the tram for forty-six minutes. He had four minutes to get to work.

He crossed the road from the tram stop and stopped outside the office building where he worked. It was a low-cost unit, identical to the hundreds of others in this neighbourhood, a box with doors and windows and cheap wiring behind the cheap plastic walls. Better get this over with, he thought with a sigh. First thing tomorrow morning I’ll go looking for a new job. He stepped through the door, climbed up the stairs to the next floor and went into the office.

Mr. Feintuch was already there; Josh suspected that he lived there, and what’s more, that he never slept. Though the time was eight twenty-nine, and he had a minute still to go, Mr. Feintuch was already making the ancient finger-on-wrist movement that signalled, You are late. Well, screw you, Josh thought, but all he said was, ‘Good morning, Mr. Feintuch,’ as he edged his way to his desk by the window. There were only two others, he saw, who were in that morning. Shay waved a good morning at him, which he returned. Chen, sitting with a mug of tea on the other end of the room, ignored him. He was already logged-in, ready to start selling. He was the second best salesman they had, after Rajani. Why was he doing the dead shift?

He sat down with a sigh. The office node logged him in automatically. He stared into the air above his desk, where the company logo slowly revolved and then dissolved to make way for a long list of names and addresses, all of them out of the city, all of them in the farms and homesteads and longhouses—but no kibbutzim, not for this one—out in the wilderness. Lonely people, who would be glad to hear his voice, who would be happy just to have someone to talk to.

‘Okay people, look alert!’ Mr. Feintuch said. ‘First person to make a sale this morning gets a free cup of coffee or tea per their choice.’

I could really do with another cup of coffee, Josh thought, and he determined to really try this time, try and get that first sale, so he could have the coffee during his break, in three hours’ time.

The first name on his list was Margaret Yen. He blinked, authorizing it, and the system connected him. Somewhere, wherever Margaret Yen was, she would be hearing whatever sound it was she had chosen to tell her someone wanted to speak to her. He hoped she didn’t filter her calls. He hoped she was bored, alone in a house, just waiting for a friendly sales-person to contact her. God bless the lonely ladies of Mars, he thought.

The name revolved in the air, once, twice, a third time…and there she was.

She was heavy set, a part-Chinese part-Caucasian woman, with a deep tan and wrinkles around the eyes. ‘Yes?’

‘Ms. Yen,’ Josh said enthusiastically, smiling, nodding his head, ‘Are your plants wilting? Do you find it hard to breathe? Are oxygen levels dropping in your home to unacceptable levels?’

The woman looked at him blankly. ‘Actually,’ she began, but Josh was only just starting. ‘I am calling on behalf of the Kobayashi Consortium,’ he said, lowering his voice confidentially. ‘You must know that the Kobayashi Consortium—Friendly Cows at Friendly Prices, is our motto—are the world’s largest purveyors of cattle products. Our cows are famous throughout the inner system for the tenderness of their meat, the quality of their milk, and their unbeatable, organic, fresh, Mars-adapted manure. Lady, I am here to tell you that, for one day only, we have a very special deal on Kobayashi manure, and you’ve been selected especially from our database to receive that offer. Your plants–’

‘I don’t understand,’ Margaret Yen said. ‘Where did you get my details from? We get all our manure from the United Kibbutzim Movement’s co-op. We don’t–’

‘The Israelis?’ Josh laughed, derisively. Inside, depression settled, familiar and comfortable. He ploughed on. ‘Surely you realise their manure contains numerous instances of chemical impurities? They feed their cattle on Other-modified Soya, untested by impartial scientists, a feed which can lead to cancer, still births—even worse, unnatural births. Unlike the co-op, Kobayashi guarantees you–’

‘My husband is an Israeli,’ Margaret Yen said. ‘What was your name again? I am going to report you to–’

Josh blinked and terminated the connection. Margaret Yen’s image disappeared and he leaned back in his chair, and felt like crying.

There was a short, musical ping. He lifted his head and saw Chen raise his hand. The bastard had already made a sale.

No free coffee for you, Josh.

At that moment he hated them. He hated Feintuch, the smarmy Jewish bastard, stealing work from his own people, taking out this contract with Kobayashi, and he hated the Israelis too, for living fat and rich in their part of Mars, with their cows and their fields and their brown-tanned girls and their false fucking superiority over everyone, while he, Josh Chaplin, who was better than them in every way possible, had to live in a one-room box apartment in a co-op on Lo-Rent, in Tong Yun City, bloody immigrant city, and work doing this, selling…

Selling shit.

He felt like crying.

‘Josh? Are you okay?’

It was Shay, coming over. She must have just finished a call. Josh looked back and saw Mr. Feintuch was no longer there.

‘I’m fine,’ he said. ‘Just tired.’ He looked up and tried to smile. ‘You shouldn’t leave your desk. Mr. Feintuch–’

‘Don’t worry,’ Shay said, her eyes twinkling. ‘Boris had to leave, he got a call from his wife just now. He’ll be gone for at least forty minutes.’

‘Boris?’ Josh said. ‘Mr. Feintuch’s name is Boris?’

‘You mean you didn’t know?’

‘No, I…’ It had never occurred to him to even ask. ‘Boris Feintuch,’ he said now, trying it out. ‘Poor bastard.’

Shay laughed.

‘Well, take it easy, okay?’ she said. ‘It’s a crappy job, but it pays, you know? Don’t take it so seriously.’

‘I won’t,’ Josh said. ‘I don’t. It’s just…’

‘Yeah,’ Shay said. ‘It gets to you sometimes, doesn’t it.’

She left him there and went back to her desk. They had a list to go through, and a quota to fill. Josh stared into the air above the desk. Tomorrow, he thought. I’ll look for another job. Unless I make that big sale today.

He blinked, authorizing the next name on the list, not even looking at it, and the system connected him.

‘Yes?’ a voice said, and Josh started. He knew that soft, melodious voice, and moreover, he knew the face that it belonged to, a beautiful, oval face with slanted violet eyes, a face that was currently looking at him with raised eyebrows and a puzzled—though incredibly lovely—expression.

It couldn’t be, but…

It was Sivan Shoshanim.

TWO

‘We will not compromise our policy on sharing water resources,’ Ben Gurion was saying on the car’s radio-feed. ‘What our neighbours must realise is that water is always precious, and particularly so here, on this glorious red planet of ours. We have laboured hard to reach the stage where we no longer suffer a chronic shortage of that most precious commodity, the basis of all life, the basis of our new life, and we will not, will not bend! I urge every citizen to consider–’

Miriam switched it off. She looked out of the window of the car. Far on the horizon a massive object was hurtling towards the ground, followed by another, then another. She braced herself, but in the event the Shenzhou’s specially-designed suspension reduced much of the aftershocks to a barely-felt tremor, and she found herself slightly disappointed.

Water, she thought. We have plenty of water. Those rocks over there, those giant balls of frozen water streaking across the sky, they belong to us. We’re hurling them down from orbit faster than we can process them. Every way you want to look at it, we’re rich with it. We could give some of it away.

If we wanted to.

The problem discussed on the radio today was the usual one. There was an accident in the Dimitrovgrad reservoir, which lay close to the New Israeli border, and the Moskovites were half-asking, half-demanding help. If only they didn’t bluster so much, she thought, we might actually help them, but it’s the way they go about it, banging on about duty and responsibility—that really doesn’t help.

It also didn’t help that the accident, most likely, was not an accident at all, but the result of saboteurs working on behalf of—well, who knew. An internal faction, most likely. The Russians always fought amongst themselves. What was that saying? All you needed was to put two Russians in a room and you got yourself a power struggle.

Maybe it was the Born Again Martians, she thought. The Re-Born. As if by wasting all that water they could somehow irrigate the dead sands and turn the planet back onto the Way.

The Way It Was. Or, at least, she thought, the way they imagined it had once been. As a teenager Miriam, like most people at that age, had been fascinated by the Born Again. She had attended a couple of sessions, and saw the Way for herself. She remembered it vividly. She had entered the small room and the space was reconfigured around her. It was hot, and she could taste sweat, forming on her upper lip. Lush, green plants grew all around her, large vines sprouting blood-red flowers, and as she walked through the vegetation she arrived at a wide canal, glorious blue water flowing gently, and she dipped her hands in the water and felt their refreshing coolness. Then she raised her head and saw the boat, a strange silver vehicle bobbing calmly on the water—and, standing on the open deck, the four-armed creature. The Martian. He had beautiful eyes, she remembered that… He talked to her, telepathically, told her tales of his ancient civilization, of the great cities of his race, of…

Miriam shook her head and smiled. That was when the Re-Born really got to you, when you were young. When you could still believe, even in impossible things, like Martians. She had seen The Way It Was but, in the end, she didn’t see how the fantasy could be sustained. You might as well believe in time travel.

The road into Tong Yun City was clear, and she could no longer see the falling water meteors. She initiated a new radio channel, and was pleased when Vusi Sikelele’s classic I Lost my Love on the Martian Sands came on. She hummed along with the music and, soon, the great dome of the city came into view ahead.

As she drove through the narrow streets a running man startled her, and she almost swerved. She honked, but he was already gone, and she drove past the tram stop and onwards, while the radio played Sivan Shoshanim’s latest hit, They Said it Would Only Last a Life-Time