6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

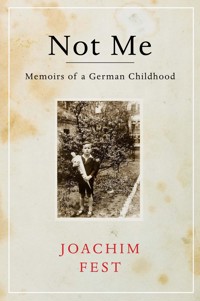

From the author of Inside Hitler's Bunker, the critically acclaimed book that inspired the equally acclaimed 2005 film Downfall. Few other historians have shaped our understanding of the Third Reich as Joachim Fest. Fierce and intransigent, German-born Fest was a relentless interrogator of his nation's modern history. His analysis, The Face of the Third Reich, his biographies of Adolf Hitler and Albert Speer and his descriptions of the last days in the Fuhrer's bunker have all reached a worldwide audience of millions. But how did the young Fest, born in 1926, personally experience National Socialism, the Second World War and a catastrophically defeated Germany? In Not Me, the memoir of his childhood and youth, Joachim Fest chronicles his own extraordinary early life, providing an intimate portrait of those dark years of conflict. Whether describing his Catholic home in a Berlin suburb, his father's resistance of the regime and subsequent teaching ban, his own expulsion from school, or Aunt Dolly's introductions to the operatic world, these are the long-awaited personal reflections of a born observer the exactitude of whose prose is as sharp as the memories he describes.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

Not Me

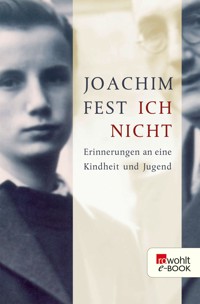

The author with his father in early 1941

First published in Germany by Rowohlt Verlag GmbH in 2006

First published in Great Britain in hardback and airside and export trade paperback in 2012 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Rowohlt Verlag GmbH 2006

Translation copyright © Martin Chalmers, 2012

The moral right of Joachim Fest to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

The moral right of Martin Chalmers to be identified as the translator of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 84354 931 4

Trade Paperback ISBN: 978 1 84887 575 3

eISBN: 978 0 85789 960 6

Designed by Nicky Barneby @ Barneby Ltd

Set in 11.75/15pt Quadraat

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For My Parents

Contents

Foreword

1. How Everything Came Together

2. The World Falls Apart

3. Even if All Others Do . . .

4. Just Don’t Get Sentimental!

5. Leave-takings

6. Alien Worlds

7. Friends and Enemies

8. Of the Soldier’s Life and of Dying

9. The Escape

10. Not Home Yet

11. Retrospect and a Few Leaps Ahead

Postscript

Notes

Index

Foreword

One usually begins to write memoirs when one realizes that the greater part of one’s life has been lived, and what one intended to do has been achieved more or less well. Instinctively, one looks back at the ground covered: one is startled at how much has sunk into obscurity or has disappeared into the past as dead time. One would like to capture what is more important or save it for memory, even as it is fading into oblivion.

At the same time one comes face to face with the effort required in calling up the past. What was it my father said when my mother reproached him for his pessimistic moods, when she tried to coax him into a degree of flexibility towards those in power? What was the name of the German teacher at Leibniz Grammar School, who, in front of the boys, regretted that I was leaving his class? What were the remarks Dr Meyer made as he accompanied me to the door on my last visit – were they sombre or merely ironically resigned? Experiences, words, names: all lost or in the process of disappearing. Only some faces remain, to which, if one kept poking around long enough, a remark, an image or a situation could be linked. Other information was provided by family tradition. But quite often the thread was simply broken. That also had something to do with the fact that when my family was expelled from our home in Karlshorst all keepsakes, notes and letters were lost. Likewise, the family photos. The pictures in this book were mostly given back to us after the war by friends who had asked for them at some point and were able to save their possessions through the upheavals of the times.

I would have been unable to record my earliest memories if in the early 1950s I had not had a radio commission to write an account of recent German history. Wherever possible I supplemented the published historical studies – which at that time were far from abundant – with conversations with contemporaries. Most frequently, however, and also at greatest length, I consulted my father, who, as a politically committed citizen, had experienced the struggles and suffering of the time as more than a mere observer. Naturally, these conversations soon extended to more personal matters and drew attention to the family’s troubles, which I had lived through and at the same time hardly noticed.

On the whole I noted down my father’s observations only as headings. That caused me some difficulties when I came to write this book, because if I could not reconstruct the context of a remark it inevitably remained sketchy and frequently had to be left out. Some of his opinions did not stand up in the face of the knowledge I had meanwhile acquired. In the initial draft, however, I reproduced rather than corrected them, because they seemed important as the opinions of someone present at the time; in part they reflect not today’s historical view, but the perceptions, worries and disappointed hopes of a contemporary.

To make the book more readable I have also taken the liberty of reproducing some of my notes as direct speech. A historian could not possibly proceed in such a way, but it may be permitted the memoirist. Wherever possible these dialogues maintain the tone as well as the content of what was said. When individual remarks are placed in quotation marks they faithfully reproduce a comment, as far as memory allows.

My observations make no claim to be indisputably valid. What I write about the friends of my parents, about teachers and superiors remains my view alone. I present Hans Hausdorf and Father Wittenbrink, the Ganses, Kiefers, Donners and others only as I remember them. That may not be accurate or even fair in every respect. Nevertheless, I was not prompted by any prejudice.

I have dealt analytically with the years with which the following pages are concerned in several historical accounts. For that reason in the present book I could largely dispense with abstract reflections. They are left to the reader. At any rate I have not written a history of the Hitler years, but only how they were reflected in a family and its surroundings.

In writing this book I have accumulated many debts of gratitude. Here I would like to mention only Frau Ursel Hanschmann, Irmgard Sandmayr and my friend Christian Herrendoerfer; and my fellow prisoners of war Wolfgang Münkel and Klaus Jürgen Meise. The latter successfully escaped from the POW camp some time before my failed attempt. I owe particular thanks to my editor Barbara Hoffmeister for her numerous important comments. Finally, the many friends of my youth who helped me with the order of events, dates and names should be acknowledged.

Joachim Fest

Kronberg, May 2006

1.

How

Everything

Came

Together

The task I have set myself is called recollection. The majority of the occurrences and experiences of my life have as with everyone faded from memory. Because memory is ceaselessly engaged in casting out one thing and putting something else in its place or superimposing new insights. The process is unending. If I look back over the whole time, a flood of pictures presses forwards, jumbled up and random. Whenever something happened, no idea was associated with it, and only years later was I able to discover the hidden watermark in the documents of life and perhaps interpret it.

But even then images intervene, especially when it comes to the early years: the house with the wilderness-like undergrowth at the sides (later, to our sorrow, removed thanks to our parents sense of orderliness); catching crayfish in the River Havel; our much-loved nursemaid Franziska, who one day had to return to her home in the Lausitz; the trucks which raced down the streets with a bright flag, packed with bawling men in uniform; the excursions to Sanssouci or Lake Gran, where our father told us a story about a Prussian queen, until we began to get bored with it. All unforgotten. And once we children had reached the age of ten, we were taken one Sunday in summer when the band was playing and the aristocrats two-wheel carriages were standing in front of the Emperors Pavilion to the racetrack. Like the district of Karlshorst in Berlin it had been developed by my grandfather on the out-of-the-way Treskow Estate, and had later gained the reputation of being the largest steeplechase course in the country. As if it were yesterday I see the parade of huge horses with the little jockeys in their colourful clothes, and the solemnly pacing gentlemen in their mouse-grey morning coats with bow ties at their throats and bulging starched fronts. The women, on the other hand, mostly stuck together and watched one another in the shadow of hats as big as wheels in the hope that some rival could be discovered and dismissed with a crushing remark.

It was a strange, genteel world that had brought my grandfather to Karlshorst. He had been born into the respected Aachen drapers family of Straeter, whose branches were spread across the Lower Rhineland and which was so wealthy it could afford every two years to hire a train for a pilgrimage to Rome, where its members were received by the Pope in a private audience. Circumstances had brought him into contact with the high nobility; in his twenties he was already Travel Marshal of the Duke of Sagan, and a little later he went to Donaueschingen as Inspector of Prince Frstenbergs Estates. His early years were largely spent at aristocratic residences in France, and at Chateau Valenay (once the property of Prince Talleyrand) he had got to know my grandmother, who came from a Donaueschingen family and was a lady-in-waiting to the Frstenbergs. It was a great love that lasted until old age, when the Second World War smashed everything. For a long time French was mostly spoken in the family and the cooking of the house was also French with onion soup, duck pt and crme caramel. Most of the classics of the neighbouring country were in my grandfathers library in awe-inspiring, leather-bound editions. I sometimes heard him declaiming Racine as he walked up and down in front of his desk, but his favourite authors were Balzac and Flaubert.

My grandfather had arrived in Berlin in 1890, at the time of a sensational murder case. The Heinzes, a married couple, had killed a night watchman. The Heinze Case, which my grandfather and many others often compared to the murders of Jack the Ripper, had the side-effect of drawing attention to the housing conditions of the poor. As a result two and later three groups of wealthy families joined together to establish philanthropic societies to build housing estates. The largest of these projects was initiated by the judge Dr Otto Hentig with Prince Karl Egon zu Frstenberg in charge. Also involved were the Treskows, who had resided in nearby Friedrichsfelde (outside Berlin) since 1816, as well as August von Dnhoff, the Lehndorffs and other respected families. The well-known architect Oscar Gregorovius also played a part, as well as, somewhat later, the more famous Peter Behrens.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!