Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

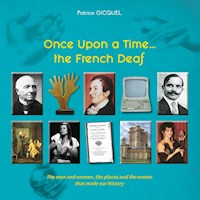

Learn all about the important moments in deaf history through the explanatory texts, short biographies and valuable illustrations of this book, the French bible on the deaf. It's a fascinating read. This book has a lot to teach those interested in the world and culture of the deaf, as well as to new générations of deaf people who may wish to follow in the footsteps of their elders.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 165

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction

Note to the reader

Prehistory

Antiquity

The Middle Ages

The Renaissance

The Seventeenth Century

The Eighteenth Century

The French Revolution

The Nineteenth Century

The Twentieth Century (1

st

part)

World War I

The Twentieth Century (2

nd

part)

World War II

The Twentieth Century (3

rd

part)

The Twenty-first Century

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

INTRODUCTION

Dear Reader,

At the first European Colloquium on the History of the Deaf, which took place in 1992 in Rodez, France, I delved deep into the history of the deaf.

The people I met and the discussions we had were a fascinating exploration of deaf identity and deaf culture.

I was born to a deaf family, but it was at the Colloquium of Rodez that I learned that we, the deaf, have a culture like any minority–because we are a minority–and ours is very rich.

This was also when I developed an interest in sign language and its origins.

In the history of humanity, the deaf are often forgotten.

And yet, from Antiquity to the present day, deaf men and women have been important as artists, teachers, actors, writers, school principals, and even presidents and leaders of national and/or international associations who fully devote themselves to causes they are committed to and in which they firmly believe.

The history of the deaf also can also be interpreted as the ceaseless chronicle of a long fight to obtain equality in society: the right to education and health, access to information, general knowledge, accessibility, and so on.

With the explanatory texts, short biographies, and informative illustrations in this book, I sincerely hope that Once Upon a Time… the French Deaf will convey a reality that remains poorly understood.

The men and women, the places and the events that made our history have made significant contributions to the long-neglected history of the deaf, even though these people have made valuable contributions to world heritage.

As we enter this long, dense history of the deaf, I would also like to raise awareness among a wider audience on certain aspects of the deaf world. In particular, I am hoping that young deaf people will be able to identify with this deaf community.

I hope that in the future, new generations of the deaf will know how to fight, as did their predecessors, for the CAUSE OF THE DEAF and for the DEFENSE OF SIGN LANGUAGE.

May they be a part of:

Nonprofit organizations and clubs that defend their rights and promote the use of sign language

Schools that educate them and develop their communication

Encounters that inform their hearing friends

In short, may they be active members of today’s society.

You have this book between your hands. Please enjoy it and find inspiration in its pages.

Patrice GICQUEL, Author

NOTE TO THE READER

The events in this book are presented in chronological order.

The presentation of every event becomes apparent over the course of the pages.

The era is immediately understood.

The text aims to recount striking facts and to showcase its deaf and hearing protagonists.

The names of the deaf are written in bold face, with their last names capitalized.

Those of hearing people are in lowercase letters.

The narrative is enriched with additional information enclosed in boxes.

If a deaf witness of the event is mentioned, a biography with a photo of the person and a drawing of his or her name sign is provided in a box.

Iconography has an important place in this book.

Photos, paintings, and drawings illustrate each subject with accounts by contemporaries and lovers of history who have worked on them over time.

Maps are provided for context when necessary.

The past paves the way for the futureFrench saying

Prehistory

from 2 million years ago to 3000 BC

In Prehistoric times, the first humans began to communicate with gestures even before using spoken language.

For the Prehistoric deaf, there were no problems communicating, since communication was visual and involved gestures.

For example, by bringing bunched fingers towards the mouth, a sign that is still understandable today all over the world, a man could clearly express the idea “to eat.”

The same man could convey that he wanted to drink by pretending to pour liquid between his lips.

Prehistory was the time of instinctive, natural signs: those that expressed basic and immediate needs or vital necessities.

But were there any deaf people in Prehistory?

We can be tempted to answer “yes,” because it is likely that deafness is as old as humanity.

Antiquity

from 3000 BC to 475

Antiquity did not make the lives of the deaf easier.

It was thought that they could not be educated, or that they were stupid or crazy.

Sometimes, their birth was considered a harbinger of misfortunes to come.

They were sometimes welcomed because of their manual dexterity, but their intellectual abilities were rarely recognized. As a result, they were practically never introduced to the customs and religions of their contemporaries.

The right to live is the first human right. This right was often revoked from the deaf of Antiquity. It was considered shameful to be deaf. In some populations, parents would hide their deaf children. As a result, they were isolated and did not acquire spontaneous communication through contact with other deaf people.

After the Greek colonization of Marseille around 600 BC, the philosopher Plato (428–348 BC) believed that a person who could not speak could not reason.

Plato

Aristotle

His follower, Aristotle (384–322 BC), deduced that the deaf, who appeared to be irreparably ignorant, could not be educated. He did recognize, however, that the dumbness was a consequence of deafness.

And yet, when Gaul was occupied by the Romans, Pliny the Elder (23–79), wrote in his Natural History of the existence of a deaf man named Quintus PEDIUS, a grandson of Quintus Pedius Publicola, senator and speaker.

Since he was from a wealthy family, it was ordered that he be instructed in painting. He acquired a level of excellence in this art, but he died young.

His education is also mentioned as being the first of its kind for a deaf person, even though he was probably only educated in the arts.

The Gauls went so far as to sacrifice the deaf, who were considered inferior, on altars dedicated to the terrifying Toutatis, their war god.

The Middle Ages

from 476 to 1491

It seems the deaf were better integrated into community life during the Middle Ages.

Very few deaf people were beggars, and all the others worked. They were laborers, cloth merchants, butchers, ploughmen, handmaids, doormen, and even monks.

In some cases, the deaf were simply tolerated, as if they were village idiots.

From the end of the fourth century, Jérôme de Stridon (347–420), considered to be a saint, father, and doctor of the Church, recognized that “through signs and through daily conversation, through the eloquent gestures of the whole body, the deaf can understand the Gospel.”

It was not until the twelfth century that Pope Innocent III authorized the marriage of the deaf. Since they could not speak, they would say “I do” through signs.

Marriages were mixed, involving either a deaf man and a hearing woman or a deaf woman and a hearing man.

At the Cistercian monastery founded in 1098 by Robert de Molesme in the abbey of Citeaux (region of Tonnerre), monks were bound by a vow of silence.

They would communicate with each other only through signs, but their monastic sign language had very few signs in common with the language of the deaf.

Nevertheless, a number of young deaf men found themselves in the monasteries of the Benedictine monks.

The Renaissance

1492 to 1600

During the Renaissance, especially under Francis I (1494–1547), a certain way of viewing the world and of favoring the arts came about.

Mentalities changed, which was rather positive for the deaf.

Francis I had several magnificent castles built, particularly along the Loire river, and called upon major Italian painters including Leonardo da Vinci.

As a man of universal spirit, who was at once an artist, scientist, inventor, and philosopher, Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) pointed out in his Treatise on Painting:

“The deaf are masters in terms of movement; from afar they understand what people are speaking about, as long as the speaker accompanies his words with movements of the hands…”

Priests, on the other hand, who possessed knowledge and were tasked with instructing the children of wealthy families, noticed that it was possible to educate the deaf.

Michel de Montaigne (1533–1592), a French writer, understood that the mute could converse, argue, and tell stories using signs.

He also stated that they lacked nothing in the perfection of making themselves understood.

He confirmed that the deaf had already come together in communities, well before the sixteenth century.

By decision of the Parliament of Paris on October 27, 1595, if the deaf did not know how to read or write, they could not sell or bequeath their property after death without the consent of their legal guardians. The legal guardians would negotiate and sign contracts on their behalf.

Despite this, a deaf man named Anthoine de LAINCEL (1525–1611), Lord of Saint-Martin-de-Renacas (in the Alps of Haute-Provence), expressed himself through signs and had an interpreter at his disposal. He got involved in wars. He managed his accounts and drafted his will in drawings.

Opposite: his famous account book

The book contains twelve pages, where objects bought for his own use and for his family were depicted in very realistic images, drawn with a quill and followed by numbers (pounds, shillings, and pence).

The Seventeenth Century

1601 to 1700

Circa 1605, during a tour of his diocese, Saint Francis de Sales (1567–1622), Bishop of Geneva and resident of Annecy, met a deaf man named MARTIN.

MARTIN, aged between 25 and 30 years old, was not educated. Saint Francis de Sales provided him with religious instruction through signs, prepared him for communion, and then took him as a servant.

As the first private tutor of the deaf known in France, Francis de Sales was, much later, declared patron saint of the deaf by Pope Pius IX.

Philosopher and scholar René Descartes (1596–1650), wrote in one of his letters: I say speech or other signs, as the mutes use signs in the same way as we use the voice.

The manual language used by the deaf at the time appears to have had the same qualities as vocal languages.

In Toulouse, the will of a deaf painter and writer by the name of GUIBAL, which he wrote himself, was disputed by his heirs but was approved on August 6, 1679, by the Parliament (civil court).

The main heir provided letters and other papers drafted by the deaf man to prove that GUIBAL knew how to write.

Witnesses claimed that, when the man went to shops, he would haggle in writing over the price of the things he wanted to buy.

But since France was governed by Louis XIV (1638–1715), life was very hard during the second half of this century. People suffered from poverty, famine, and war. We can imagine that the deaf were often among the first victims.

The Eighteenth Century

1701 to 1789

In the eighteenth century, the deaf led lives similar to those of hearing people. These included menial jobs in Paris, or animal care and field work in the countryside.

The manual language they used was not an obstacle that could not be overcome.

In his Letter on the Deaf and Mute, writer and philosopher Denis Diderot (1712–1784) wrote that to obtain “the real notions of the formation of language,” one must see “those whom nature deprived of faculties to hear and to speak.”

Opposite: one of his numerous drawings in the abbey’s library

Circa 1675, at the abbey of Saint John of Amiens (held by the Premonstratensian Order), Etienne DE FAY, deaf and mute by birth, was placed with the monks. They successfully taught him reading, writing, mathematics, mechanics, drawing, holy and secular history (especially the history of Franc), and architecture.

As an adult, he even became an architect and a remarkable scholar.

By 1735, a five-year-old child born deaf and mute named Azy D’ETAVIGNY, entered the Saint John’s abbey in Amiens. His father had brought him there to be educated along with four or five other deaf children who were being taught by an old deaf man, Etienne DE FAY, a man skilled at expressing himself through signs.

This was the first example known in France of a deaf person using sign language to teach deaf students.

Etienne DE FAY

Amiens (Somme), 1670–1750.

He was known as the old deaf man of Amiens.

At the age of five, he entered Saint John’s abbey in Amiens. He was educated by the monks, who were bound by a vow silence and used monastic sign language.

He later lived in the abbey as a boarder and volunteer.

He was charged with acquiring provisions, and would haggle in writing on shopping trips. He was also an architect and drafted building plans when, in 1712, the monastery was to be renovated and

expanded. In 1718, the bishop of Amiens visited the rebuilt abbey and deemed it “the most beautiful house in the city.”

He also made contributions to the library and founded a small private museum in the abbey.

In seven hundred-fifty pages of drawings, he reproduced the plans of the abbey and all its treasures. Today these manuscripts are preserved at the municipal library of Amiens.

Between 1725 and 1743, he educated at least four deaf children born to wealthy families: Jean-Baptiste DES LYONS, François MEUSNIER, François BAUDRANT, and Azy D’ETAVIGNY.

A decade later, Azy D’ETAVIGNY, who spent between seven and eight years in Etienne DE FAY’s school, took articulation lessons given by Jacob Rodrigue Pereire (1715–1780) in Beaumont-en-Auge, near Caen.

Pereire settled in Paris with his student in April, 1749. His home served as a pension for the young Azy D’ETAVIGNY and for the other deaf students who were entrusted to him over the coming years.

A priest by the name of Charles-Michel de L’Epée (1712–1789) met two deaf sisters through Father Vanin in Paris in 1760. The sisters communicated with signs known only to them.

The abbot of L’Epée then realized that a portion of the deaf population did not have access to an educational system suited to their condition. He decided to convert his house on the rue des Moulins to a school and developed the methodical signs that he used in his teachings.

The number of students grew over the years, from thirty in 1771, to more than sixty in 1784, and seventy-two in 1785.

King Louis XVI (1754–1793) even attended classes in which the deaf children wrote on the board what the abbot of l’Epée spelled to them with using dactylology with his hands.

His method gained recognition as he trained other hearing teachers of the deaf, who came from all over France and from several European countries.

In 1776, the abbot of l’Epée anonymously published The Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb Using Methodical Signs, a book promoting a universal language. The book addressed Europe as a whole and was met with hostility by many private tutors, including Pereire, who held their methods secret.

Other deaf schools were quickly established in France, in Angers in 1777 and Bordeaux in 1786.

On August 1, 1773, a deaf teenager was found abandoned in Cuvilly, on the road to Péronne (Somme). He was ultimately placed at the Hôtel-Dieu of Paris where the abbot of l’Epée met him in January, 1776, took an interest in educating him, and started a search to establish his true identity.

The abbot of l’Epée became convinced that the teenager he called Joseph was in reality Guillaume, the son of the count of Solar, from Toulouse. The child was thought to have been entrusted to a young law student, Cazeaux, and abandoned at his mother’s request.

A series of testimonies and contradictory judgments were given over the course of several years.

In 1792, the final judgment asserted that Joseph had no relation to the family of Solar.

Such was the fate of deaf children born to noble families: these “embarrassing” offspring were removed from the family. They were either hidden in a secret house or convent, or were purely and simply abandoned.

Opposite: cover of the book by DESLOGES

In 1779, deaf man Pierre DESLOGES wrote and published a book entitled A Deaf and Dumb Man’s Observations on an Elementary Education Course for the Deaf and Dumb to contradict the thinking of abbot Deschamps (1745–1791), who founded a small school for the deaf in Orléans.

There, a dozen students learned to speak and lip-read.

Abbot Deschamps had just published a book on his oralization method for the deaf: An Elementary Education Course for the Deaf and Dumb.

Pierre DESLOGES intended to defend the manual method that he deemed useful in the instruction of the deaf, carrying on the tradition of the abbot of l’Epée.

One mustn’t overlook Claude-André DESEINE, one of the first deaf sculptors and figure artists who, in 1786, fashioned the first bust of the abbot of l’Epee, during his lifetime. It was a symbol of gratitude to his benefactor.

As was the case for most deaf people in his situation, Claude-André DESEINE was forbidden from managing his own inheritance for the duration of his life.

Pierre DESLOGES

Born in 1742 in Grand-Pessigny, near La Haye, diocese of Tours.

The time and the place of his death are unknown.

At the age of seven, a case of smallpox left him deaf and practically mute.

At twenty-one, he made his home in Paris and eked out a living as a bookbinder.

For a long time, he met no other deaf people. He was already twenty-seven years old when he met the first one.

Ten years later, he published a remarkable book entitled A Deaf and Dumb Man’s Observations on an Elementary Education Course for the Deaf and Dumb. Since he had not trained under the abbot of l’Epée, he acquired and developed the rudiments of French over time and through hard work thanks to the books he read.

He is the first deaf man in France known to have written a book.

Claude-André DESEINE

Paris, April 12, 1740–Petit-Gentilly, December 30, 1823.

Deaf from birth, he was one of the first students of the abbot of l’Epée in the 1760s, when he was twenty years old.

In 1780, he became one of France’s first deaf sculptor-figure artists after studying at the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture.

The four government regimes that followed (the Revolution, the Consulate, the First Empire, and the Restoration) were a source of inspiration to him.

This is how he ended up creating terracotta busts of several celebrities: Mirabeau (currently owned by the Museum of Rennes), Robespierre (at the Museum of Vizille), the wife of Danton (whose husband dug up the body so that he could make a molding of the dead woman’s face; bust displayed in the museum of Troyes), and Pope Pius VII during his journey to Paris in 1805.

Other busts are on display at the Louvre: the ambassador of the sultan of Mysore and his nephew.

He had no established residence, but lived with patrons or friends who agreed to accommodate him for a few days in exchange for a portrait or a sculpture.

Interestingly, he always signed his works “Deseine the deaf,” to distinguish himself from his brother, Louis-Pierre, who was awarded the Grand Prix de Rome for sculpture in 1780.