Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

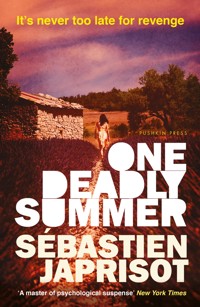

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

Described as 'the Graham Greene of France' by The Independent, cult French noir writer Japrisot brings us a classic tale of lust and revenge set in the French countryside.Car mechanic Fiorimond is irresistibly drawn to beautiful, provocative Elle, a recent arrival in his sleepy Provence village. Their relationship develops quickly, but even as they make plans to marry, Fiorimond doesn't know what to make of his bride-to-be: is she an enigma or simply vacuous? In fact the troubled Elle is on a mission to exact revenge on Fiorimond's family for a crime committed decades earlier, with a plan that will ultimately destroy all their lives, including hers.Set in the 1970s, and available in English again for the first time in many years, this is a true classic of French suspense. It has everything: stylish writing, clever construction, an unforgettable leading lady, and most importantly leaves the reader guessing until the very last page.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 588

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Sébastien Japrisot was a prominent French author, screenwriter and film director, and the French translator of J. D. Salinger. He is best known for A Very Long Engagement, which won the Prix Interallié and was made into a film by Amélie director Jean-Pierre Jeunet. One Deadly Summer won the Prix Deux Magots in 1978 and the film adaptation starring Isabelle Adjani won the César Award 1984. Born in Marseille in 1931, he died in 2003.

Alan Sheridan is the author of Andrée Gide: A Life in the Present. He has translated works by Sartre, Lacan, Foucault and Jean Lacouture.

Praise for One Deadly Summer

‘The most welcome talent since the early Simenons’

New York Times

‘A gripping tale of hatred, revenge, and lust . . . A sinister spellbinder’

Publishers Weekly

‘Japrisot’s talent lies for one part in the clever construction of his novels that mimics a game of Meccano, each piece slotting neatly, one into another. Of course, it also lies in the writing that is simple, rhythmical, surprising, phonetic and lyrical’

Le Point

‘Sébastien Japrisot holds a unique place in contemporary French fiction. With the quality and originality of his writing, he has hugely contributed to breaking down the barrier between crime fiction and literary fiction’

Le Monde

‘Unreeled with the taut, confident shaping of a grand master . . . Funny, awful, first-rate. In other hands, this sexual melodrama might have come across as both contrived and lurid; here, however, it’s a rich and resonant sonata in black, astutely suspended between mythic tragedy and the grubby pathos of nagging everyday life’

Kirkus Reviews

Praise for A Very Long Engagement

‘A classic of its kind, brewing up enormous pathos undiluted by sentimentality’

Daily Telegraph

‘The narrative is brilliantly complex and beguiling, and the climax devastating’

Independent

‘Riveting . . . A fierce, elliptical novel that’s both a gripping philosophical thriller and a highly moving meditation on the emotional consequences of war’

New York Times

‘Diabolically clever . . . The reader is alternately impressed, beguiled, frightened, bewildered’

Anita Brookner, Man Booker-winning author of Hotel du Lac

‘A kind of latter-day War and Peace . . . A rich and most original panorama’

Los Angeles Book Review

‘Precisely, surprisingly evocative of the lingering pain of mourning and the burdens of survival’

Kirkus Reviews

One Deadly Summer

One Deadly Summer

SÉBASTIEN JAPRISOT

Translated from the French by Alan Sheridan

Adapted by Gallic Books

Pushkin Press

First published in France as L' été meurtrier

by Éditions Denoël, Paris, 1977

Copyright © Éditions Denoël, 1977

First published in Great Britain in 1980

by Secker & Warburg

This ebook edition first published in 2018

by Gallic Books

59 Ebury Street, London, SW1W 0NZ

All rights reserved

© Gallic Books, 2018

The right of Sebastien Japrisot to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

ISBN 9781805334224 epub

The Executioner

The Victim

The Witness

The Indictment

The Sentence

The Execution

“I’ll be judge, I’ll be jury,”

said cunning old Fury:

“I’ll try the whole cause,

and condemn you to death.”

Lewis Carroll,Alice in Wonderland

The Executioner

I said OK.

I usually agree to things. Anyway, I did with Elle. I slapped her once, and once I beat her. But apart from that, she usually got her own way. I don’t even know what I’m saying any more. I find it hard talking to people, except my brothers, especially Michel. We call him Mickey. He carts wood around in an old Renault truck. He drives too fast. He’s as thick as shit.

I once watched him drive down into the valley, on the road that follows the river. It’s all twists and turns and sudden drops, and the road is hardly wide enough for one car. I watched him from high up, standing among the fir trees. I managed to follow him for several kilometres, a small yellow dot, disappearing and reappearing at every bend. I could even hear his engine, and the lumber bouncing up and down with every bump. He got me to paint his truck yellow when Eddy Merckx won the Tour de France for the fourth time. It was a bet. He can’t even say hi, how are you, without talking about Eddy Merckx. I don’t know who he gets his brains from.

Dad thought Fausto Coppi was the greatest. When Coppi died, he grew a moustache as a sign of mourning. For a whole day he never spoke, he just sat on an old acacia stump in the snow-covered yard, smoking his American cigarettes, which he rolled himself. He went around collecting butts, only American ones, mind you, and he rolled these incredible cigarettes. He was a character, our father. He’s supposed to have come from southern Italy, on foot, pulling his pianola behind him. When he came to a village or town he’d stop in the square and get people dancing. He wanted to go to America. They all want to go to America, the Ritals. In the end he stayed, because he didn’t have the money for a ticket. He married our mother, who was called Desrameaux and came from Digne. She worked in a laundry and he did odd jobs on farms, but he earned practically nothing, and of course you can’t go to America on foot.

Then they took in my mother’s sister. She’s been deaf since the bombing of Marseille, in May 1944, and she sleeps with her eyes open. In the evening, when she sits in her chair, we never know whether she’s asleep or not. We all call her Cognata, which means sister-in-law, except our mother, who calls her Nine. She’s sixty-eight, twelve years older than Mamma, but Mamma looks the older of the two. All she does is doze in her chair. She only gets up for funerals. She’s buried her husband, her brother, her mother, her father, and our father, when he died in 1964. Mamma says she’ll bury us all.

We’ve still got the pianola. It’s in the barn. For years we left it out in the yard, and the rain blackened and blistered it. Now it’s the dormice. I rubbed it with rat poison, but that didn’t work. It’s riddled with holes. At night, if a dormouse gets inside it, it makes a real racket. It still works. Unfortunately, there’s only one roll left, ‘Roses of Picardy’. Mamma says it wouldn’t be able to play anything else anyway – it’s got too used to that tune. She says Dad once dragged it all the way to the town to pawn it. They wouldn’t take it. What’s more, the road into town is downhill all the way, but the return journey . . . Dad was exhausted – he already had a weak heart. He had to pay a truck driver to bring the piano back. Yes, Father was a businessman, all right.

The day he died, Mamma said that when my other brother, Boo-Boo, was grown up, we’d show them. All three of us boys would set ourselves up with the piano, in front of the Crédit Municimate, the bank in town, and play ‘Roses of Picardy’ all day. We’d drive everybody crazy. But we never did it. He’s seventeen now, Boo-Boo, and last year he told me to put the piano in the barn. I’ll be thirty-one in November.

When I was born Mamma wanted to call me Baptistin, after her brother, Baptistin Desrameaux, who drowned in a canal trying to save someone. She always says if we see anyone drowning we’re to look the other way. When I became a volunteer fireman, she got so angry with me she kicked my helmet around the room. She kicked it so hard she hurt her foot. Anyway, Dad persuaded her to call me Fiorimondo, after his brother – at least he died in his own bed.

Fiorimondo Montecciari – that’s what’s written in the town hall and on my papers. But it was just after the war, and Italy had been on the other side, and it didn’t look right. So they called me Florimond. Anyway, my name’s never done me any good. At school, in the army, anywhere. Mind you, Baptistin would have been worse. I’d like to have been called Robert. I often used to say I was called Robert. That’s what I told Elle at first. Just to top it off, when I became a volunteer fireman they started calling me Ping-Pong – even my brothers. I got into a fight over it once – the only time in my life – and I got a name for being violent. I’m not a violent person at all. In fact, it was about something else.

It’s true I don’t know what I’m saying half the time, and I can only really talk to Mickey. I can talk to Boo-Boo, too, but it’s not the same. He has fair hair – or light brown – and ours is dark. At school they used to call us macaroni. Mickey would go mad and start fights. I’m much stronger than him, but as I said, I only got into a fight once. At first, Mickey played football. He was a good football player – a right winger, I think, I’m not sure – his speciality was scoring with headers. He’d be in the middle of a crowd of players in the goal mouth, then suddenly his head would pop up, and send the ball into the goal. Then they’d all rush up and hug him, like on TV. All that hugging and kissing and lifting him up, it made me sick watching it from the stands. He was sent off three Sundays in a row. He’d get into a fight over anything – if someone grazed his shin or said something to him, anything – and he always fought with his head. He’d get hold of them by the shirt and headbutt them. Next thing, they were laid out on the ground, and who do you think got sent off? Mickey, of course. He’s as thick as shit. His hero is Marius Trésor. He says he’s the greatest football player who ever lived. Eddy Merckx and Marius Trésor: if you let him get started on those two, you’ll be there all night.

Then he dropped football and took up cycling. He’s got a licence and everything. He even won a race at Digne this summer. I went to it with Elle and Boo-Boo, but that’s another story. He’s nearly twenty-six now. They say he could still go professional and make something of himself. Maybe he could – I don’t know. He’s never even learned to double-clutch. I don’t know how that old Renault is still going, even if it is painted yellow. I have a look at the engine every couple of weeks – I wouldn’t want him to lose his job. When I tell him to be careful and not to drive like an idiot, he looks all sorry for himself, but really he doesn’t give a shit, just like when he swallowed some chewing gum for the first time. When he was a kid – he’s five years younger than me – he was always swallowing chewing gum. Each time we thought he’d die. Still, at least I can talk to him. And I don’t have to say much – we go back all the way, after all.

Boo-Boo started school while I was doing my military service. He had the same teacher as us, Mlle Dubard – she’s retired now. Every day he took the same route to school as we had – three kilometres over the hill, and at times the path is practically vertical – only fifteen years later. He’s the cleverest of the three of us. He passed his exams and he’s now in the final year of sixth form. He wants to be a doctor. This year he’s at school in town. Mickey drives him in every morning and brings him back at night. Next year he’ll have to go to Nice or Marseille or somewhere. But in a way, he’s already left us. He’s usually very quiet. He just stands there stiffly, his hands stuck in his pockets, shoulders back. Mamma says he looks like a lamp post. His hair is long and he’s got eyelashes like a girl – he’s always being teased about it. But I’ve never seen him lose his temper. Except with Elle, once maybe.

It was at Sunday lunch. He said something, just a few words, and she left the table and went up to our room, and we didn’t see her for the rest of the afternoon. That evening she said I would have to talk to Boo-Boo, stick up for her. So I talked to him. It was on the cellar stairs. I was sorting through empty bottles. He said nothing, just started crying. He didn’t even look at me. I could see he was still a baby. I wanted to put my hand on his shoulder, but he pulled away, then walked off. He was supposed to come with me to the garage to see my Delahaye, but he went to the cinema or out to a disco somewhere.

I’ve got a Delahaye, a real one, with leather seats, but you can’t really drive it. I got it from a scrap dealer in Nice, in exchange for a clapped-out old van I’d bought from a fishmonger for two hundred francs – we then went to the café and spent the money on drinks. I’ve replaced the engine, the transmission, everything. I don’t know what’s wrong with it. It should be fine, but when I take it out of the garage where I work, the whole village is there waiting for it to break down. And it does. It stalls and starts to smoke. They say they’re going to set up an antipollution committee. My boss goes mad. He says I’m stealing parts, and I spend too many nights there wasting electricity. Sometimes he gives me a hand. But mostly he doesn’t want to know. Once I drove all the way through the village and back before it broke down. That was a record. When the car began to smoke, no one said a word. They couldn’t get over it.

There and back, from the garage to our house, is 1,100 metres. Mickey checked it with the odometer on his truck. If a 1950 Delahaye, even one allergic to cylinder-head gaskets, can do 1,100 metres, it can do more. That’s what I said, and I was right. Three days ago, on Friday, it did more.

Three days.

I can hardly believe time always passes at the same speed. I went away, then I came back. It felt as though I’d lived through a whole other lifetime, and everything had stopped while I’d been away. What struck me most in town last night when I came back was that the poster outside the cinema hadn’t changed. I’d seen it during the week, coming back from the station. At the time I didn’t even stop to see what was on. Last night – it was before the intermission, and they’d left the lights on outside – I was sitting at the café across from it, in the little street behind the old market place, waiting for Mickey. I’ve never looked at a poster for so long in my life, but I couldn’t describe it. I know it showed Jerry Lewis, of course, but I can’t even remember the name of the film. I was thinking about my suitcase. I couldn’t remember what I’d done with it. And anyway, it was in that cinema I first saw Elle, long before I ever talked to her. I’m supposed to be on duty there on Saturday evenings to stop young lads smoking.That suits me fine – I get to see a film. On the other hand, it’s a pain in the neck, because they all call me Ping-Pong.

Elle stands for Eliane, but we’ve always called her Elle. She came here last winter, with her father and mother. They’re from Arrame, on the other side of the pass. It’s the village they demolished to build the dam. Her father was brought over in an ambulance, just after the furniture van. He used to work as a road mender. Then, four years ago, he had a heart attack in a ditch. He fell head first into the dirty water. Someone told me he was covered in mud and dead leaves when they brought him home. His legs have been paralysed ever since – there’s something wrong with his spine, I think, I don’t know – but he spends all his time yelling at people. I’ve never actually seen him – he stays in his bedroom – but I’ve heard him shouting. He doesn’t call her Eliane, either – he usually calls her Bitch. He says worse things than that.

Her mother’s German. He met her during the war, when he was doing forced labour. She loaded anti-aircraft guns during the bombing raids. I’m not joking. In 1945 they used girls to load guns. I’ve even seen a photograph of her wearing boots with her hair wrapped in a turban. She doesn’t say much. In the village they call her Eva Braun – they don’t like her. I know her better, of course. I know she’s a good person. That’s what she always says to defend herself: ‘I’m a good person.’ With her Kraut accent. She’s never understood a word that’s been said to her – that’s the secret. She got herself pregnant at seventeen by a poor slob of a Frenchman and she followed him. The kid died at birth and all she ever got out of our beautiful country was a road mender’s wage, people who stuck their tongues out at her behind her back, and, a few years later – on July 10, 1956 – a daughter to put in the cot that had never been used. I have nothing against her. Even Mamma has nothing against her. Once I wanted to find out who the real Eva Braun had been. First I asked Boo-Boo. He didn’t know. So I asked Brochard, who owns the café. He’s one of those who call her Eva Braun. He didn’t know. It was the scrap dealer in Nice, the one who sold me the Delahaye, who finally told me. What can you do about it? Even I call her Eva Braun sometimes.

I often saw Elle and her mother together at the cinema. They always sat in the second row. They said it was to get a better view, but they weren’t well off, and everyone thought it was to save money. I found out later that it was because Elle never wanted to wear glasses, and if she’d been in the ten-franc seats she’d never have seen anything.

I stood through the whole film, leaning against a wall. I kept my helmet on. Like everyone else I thought she was pretty, but since she’d come to live in the village I’d never lost any sleep over her. Anyway, she never so much as looked at me. She probably didn’t even know I existed. Once, after buying some ice cream, she passed close by me and looked up at my helmet. That was all she could see – the helmet. After that I asked the woman in the ticket booth to look after it for me.

I’d better explain. I’m talking about before June, three months ago. I’m talking about how things were then. What I mean is that before June, Elle impressed me in a way, but I didn’t really care that much. If she’d left the village I don’t think I’d have noticed. I could see that her eyes were blue, or grey-blue, and very big, and I was ashamed of my helmet. That’s all. What I mean is . . . oh, I don’t know . . . Anyway, things were different before June.

She always went out into the street to eat her ice cream. She always had a crowd around her, mostly boys, and they’d stand talking on the pavement. I thought she was about twenty, or a bit more perhaps, because she behaved like a grown woman, but I was wrong. The way she went back to her seat, for example. As she walked down the main aisle, she knew everyone was looking at her. She knew that the men were wondering whether she was wearing a bra or knickers – depending on which part of her they were looking at. She always wore tight-fitting skirts that showed her thighs and fitted the rest so tightly you’d definitely have seen the line of her knickers if she’d been wearing any. I was the same as all the others then. Everything she did, even when she didn’t know she was doing it, put ideas into your head.

She laughed a lot, too, very loudly. She did it to attract attention. Or she’d suddenly shake her black hair, which reached down to her waist and shone in the lamplight. She thought she was some kind of star. Last summer – not this summer – she won a beauty contest at the festival of Saint-Etienne-de-Tinée, in a swimsuit and high heels. There were fourteen of them, mainly holidaymakers. She was elected Miss Camping-Caravaning – she kept the cup and all the photos. After that she really thought she was a star.

Once Boo-Boo told her she was a star for 143 inhabitants – that’s the figure in the census for our village – at a height of 1,206 metres – that’s the height of the pass above sea level – but in Paris, or even in Nice, she’d be down at street level. That’s what he said that Sunday lunchtime. He meant she wouldn’t stand out and there were thousands of beautiful girls in Paris – he didn’t mean to be rude by using the word ‘street’. Anyway, she went upstairs, slammed the door behind her, and didn’t come down until the evening. I tried to explain that she’d misunderstood what Boo-Boo had said. Unfortunately, once she’d got something fixed in her head, nothing would budge it.

She got along better with Mickey. He’s a joker, he laughs at everything. That’s why he’s got a lot of tiny wrinkles around his eyes. And anyway, the woman in his life is Marilyn Monroe. If they opened his skull, they wouldn’t find much more inside than Marilyn Monroe, Marius Trésor, and Eddy Merckx. He says she was the greatest and there’ll never be another. And at least he could talk about her with Elle. The only photograph she could bear to see on a wall, apart from her own, was a poster of Marilyn Monroe.

It’s funny, in a way, because she was still just a kid when Marilyn died. She saw only two of her films, long after, when they were shown on TV: River of No Return and Niagara. She preferred Niagara because of the oilskin with a hood that Marilyn wore when she went to see the Falls. We don’t have colour TV, and the oilskin looked white, but we weren’t sure. Mickey had seen the film at the cinema and said it was yellow. There was a big discussion about it.

Mickey, after all, is a man – it’s understandable. Personally, I wasn’t crazy about Marilyn Monroe, but I can see what he saw in her. And anyway, he’d seen all her cinema. But Elle . . . do you know what she said? First, she said it wasn’t Marilyn’s films that interested her, but her life, Marilyn herself. She’d read a book about her. She showed it to me. She’d read it dozens of times. It was the only book she’d ever read. Then she said that even though she wasn’t a man – that was true enough – if Marilyn had still been alive, and if it was possible, she wouldn’t have needed much to get her to become one.

She talked like that. It’s an important thing, the way she talked. Boo-Boo said something interesting to me once: that you can’t trust people with a limited vocabulary – they’re often the most complicated people. We were working in the little vineyard I’d bought with Mickey, just above our house. He said I shouldn’t trust Elle’s way of saying things. She didn’t always mean what she said – she only knew a few words so she had to use the same ones to express lots of different feelings. I stopped the sulphate sprayer and said that in any case, even if he used all the words in the dictionary, whatever he said would still be rubbish. Boo-Boo was always the know-it-all, but he was wrong about this.

I knew well enough what he meant. She’d say how upset she was that Marilyn died alone in an empty house, she’d like to have been there, shown her that somebody cared, anything, to stop her from killing herself. But it wasn’t true. She always said one thing at a time, as it came into her head. Listening to her was like being hit over the head with a hammer – you just waited for the next blow. In fact, that was the best thing about her. You didn’t have to stick the pieces together to get what she really meant. You could just switch off. As for her limited vocabulary, it wasn’t just that she had gone to school wearing earplugs – she spent three years in the same class and finally it was the school that gave up on her, they couldn’t take any more – it was that she had nothing to say except that she was hungry or cold or wanted to pee in the middle of the film, and said it loud enough for everyone else to hear. Mamma once called her an animal. She looked surprised. And you know what she replied? ‘You mean, just like everyone else.’ If she’d called her a human being, she’d simply have shrugged her shoulders and said nothing. She wouldn’t have understood, and in any case she didn’t say anything when people shouted at her.

Like her idea of stopping Marilyn Monroe from killing herself – why did it matter to her? She said over and over how wonderful it was that Marilyn died like that, swallowing things, with all those photographs the next day, that she was Marilyn Monroe to the end. She said she’d have liked to have met her former husbands and to have had them, even if two out of three of them weren’t her type. She said what was a real shame was that the yellow oilskin had probably been left in some cupboard or burned; she’d spent a whole day hunting around Nice and hadn’t been able to find one. That’s exactly what she said. Zero points, Boo-Boo. Try again.

I get annoyed, but I don’t really care. Everything’s back to the way it was before June. When I used to see her at the cinema before June, I didn’t even wonder how she and her mother got back to the village. You know what it’s like in small towns – thirty seconds after the film’s over, the gates are locked, the lights go out, and there’s no one in sight. I used to come back with Mickey, in his truck, but with me driving, because I couldn’t stand being his passenger. Usually Boo-Boo was with us and we’d pick up a whole lot of kids on the road who got into the back with their scooters and everything.

One evening we counted how many people were in the back – we’d collected everyone from the town up to the pass. Eleven kilometres. I dropped them off one by one. They stood and waved in the beam of the headlights by dark tracks and sleeping houses. When one of the boys got off to say goodnight to a girlfriend who lived higher up, we had to hurry them or we’d never have got going again. Mickey said, ‘Leave them alone.’ By the time we got to the village, the truck was like a dormitory. I didn’t wake Mickey or Boo-Boo up in the front, I went around to the back with a flashlight. There they all were sitting in a line, their backs resting against a rail, good as gold, each head resting on the shoulder next to it. It reminded me of the war. I don’t know why, maybe because of my flashlight. I must have seen it in a film. For some reason I felt happy. They looked exactly what they were: sleeping kids. I switched off the flashlight and let them sleep.

I went and sat down on the town-hall steps. I looked up at the sky over the village. I don’t smoke – it affects my breathing – but it was the kind of moment when I’d have enjoyed a cigarette. On Wednesday I do training, at the station. I’m a sergeant – I’m the one who gets them all running. I used to smoke – Gitanes. Dad said I was cheap. He’d have liked me to smoke American cigarettes and save the butts for him.

Anyway, just then young Massigne came by in his van, flashing his lights because he couldn’t understand why Mickey’s Renault had stopped there, and I wondered what he was doing in our village since he lived in Le Panier, three kilometres down the hill. I raised my arm to reassure him everything was OK, and off he went. He drove to the end of the village – I could hear his engine the whole time – and came back. He stopped a few metres away and got out. I told him they were all asleep in the truck. He said, ‘Oh, OK,’ and came and sat down on the steps.

It was late April or early May, still a bit chilly but nice. His name is Georges. He’s the same age as Mickey – they did their military service together, in the Alpine Chasseurs. I’ve always known him. He’s taken over his parents’ farm. He’s a good farmer and can make anything grow from the red soil around her. I was in a fight with him this summer. It wasn’t really his fault. I broke two of his front teeth, but he didn’t report me. He said I was losing my mind, end of story.

As we sat there on the town-hall steps, I asked him what he was doing there. He said he’d just taken Eva Braun’s daughter home. He’d been a long time about it. I laughed. I can’t remember what else I did, but I do know I laughed as we sat there quietly talking men’s stuff. I was about to wake up the others, so if he’d told me he’d had the mother instead of the daughter, it wouldn’t have bothered me either way.

I asked him if he’d done it with Elle. Not that night, he said, but two or three times that winter, when her mother hadn’t gone with her to the cinema, they’d done it in the back of the van, on a tarpaulin. I asked him how she was, and he gave me all the details. He’d never got all her clothes off, it was too cold. He just took off her skirt and sweater, but he gave me all the details. So what.

When we went back to the truck, they were still sitting there, all leaning over like ears of corn. I made a sound like a bugle, and shouted, ‘Come on you lot!’ They filed out, eyes half open, forgetting their bikes at first, then taking them without so much as a thank you or goodbye, except for the Brochard girl, the café owner’s daughter, who whispered, ‘Goodnight, Ping-Pong,’ and set off home, staggering around, half asleep. Georges and I shouted after them, making jokes. Our voices echoed loudly on the dark street. Finally we woke Mickey up. He stuck his head out of the door, his hair all over the place, and called us every name under the sun.

Then I was alone with him in the kitchen – I mean Mickey, of course – and we had a glass of wine together before bed, and I told him what Georges had said. He said there were a lot of big mouths around, whose cocks would fit through the eye of a needle. I said Georges wasn’t a big mouth. He said no, that was true enough. Georges’ story seemed to interest him even less than me, but he thought about it as he drained his glass. When Mickey thinks about things, it’s unbearable. To see him concentrating so hard like that, his forehead all wrinkled, you’d think he was about to come up with something like the formula for making seawater drinkable. Eventually he shook his head several times very seriously, and do you know what he said? He said Marseille were going to win the cup. If Marius Trésor played only half as well as he had been lately, there’d be no stopping them.

Next day, or maybe it was the Sunday after, it was Tessari, a mechanic like me, who talked about Elle. On Sunday mornings one of us, Mickey or me, goes down to the café in town to bet on the horses. We place a twenty-franc combination bet for us and a five-franc one for Cognata. She says she’s a lone rider. She always takes the same figures: the 1, the 2, and the 3. She says if you’re lucky there’s no point in complicating things. We’ve won at the racetrack three times, and of course it was always Cognata who won. Twice she won two thousand francs and once seven thousand. She gave some of it to Mamma, just enough to annoy her, and kept the rest for herself, in brand-new five-hundred-franc notes. She said it was ‘just in case’ – she didn’t say in case of what. We don’t know where she’s hidden the money, either. Once Mickey and I went through the whole damned house, even the barn, where Cognata has never even set foot – not to take it, of course, just to play a trick on her – but we never found it.

Anyway, on Sundays, when I’ve bought my slips, Tessari or someone else’ll buy me a drink at the bar. Then it’s my round, then we play a third at the 421, and it goes on forever. That day it was Tessari, and we were talking about my Delahaye. I was telling him how I was going to take the engine apart and start from scratch when he nudged me and looked towards the doorway. It was Elle, with her paralysed father’s five francs, her dark hair coiled up into a bun. She’d leaned her bike against the kerb and joined a queue of people waiting to place their bets.

It was sunny outside, and she was wearing a sky-blue nylon dress that was so transparent you could almost see her naked silhouette. She didn’t look at anybody, just stood there waiting, shifting her weight from one leg to the other. You could make out the roundness of her breasts, the inside curve of her thighs, and sometimes, when she moved, almost the mound between her legs. I wanted to say something to Tessari, make a joke of it, something like, ‘You can see more when she’s in a swimsuit,’ and ‘Just look at us all’ – because there were other men at the bar who’d also turned to look – but in the end, for the two or three minutes she was in the bar, we said nothing. She got her ticket punched, she was naked against the light for a moment, then set off on her bike along the pavement and was gone.

I told Tessari I’d like to have her and asked the bartender for another pastis. Tessari said it wouldn’t be hard. He knew lots of men who already had. He mentioned Georges Massigne, of course, who brought her home from the cinema on Saturday nights, but also the local pharmacist, who was married with three kids; there was also some tourist the summer before, and even a Portuguese guy who worked at the top of the pass. He knew all this because his nephew had once gone out with the tourist and a whole group of people, and Elle had been with them. They were all a bit drunk and his nephew saw them doing it, Elle and the tourist. It was one of those evenings which ended up with couples in all the bedrooms. His nephew had told him later she wasn’t worth bothering with – she inhaled.

I said I didn’t know what ‘she inhaled’ meant. He said he’d draw me a picture. The two men next to us heard what we were saying and started to laugh. I laughed, too, to be like everybody else. I paid for the drinks, said ciao, and left. All the way home I thought about it, Elle with that man, and Tessari’s nephew watching them.

It’s hard to explain. In one way I wanted her more than ever. In another way, when I saw her in the doorway of the café, in that see-through dress, I felt sorry for her. She didn’t realise, and as soon as she was inside, out of the sun, she really looked quite respectable in her blue dress, her hair in a bun, which made her seem taller. And I don’t know why, I found her even more attractive, and it wasn’t just about wanting her. I sort of hated her, I told myself it would be easy. She’d be a pushover. Yet at the same time I was sick of the whole thing. Not just of her, either. I can’t really explain.

During the following week, I saw her go past the garage several times. She lived in the last house in the village, an old stone house that Eva Braun had fixed up as best she could, putting flowers everywhere. Usually she was on her bike. She was either on her way to buy bread or heading back home. Until then I hardly ever saw her. It’s not that she wasn’t out and about. It’s like those words you notice in the paper for the first time and then see all over the place, and are so surprised by it. I looked up from my work to see her go by, but I didn’t dare catch her eye, let alone speak to her. I thought of what Georges and Tessari had said, and as she couldn’t have cared less about me or her thighs being bare, when she was on her bike I just stood there like an idiot watching her ride away. An idiot because it had an odd effect on me. The boss noticed once. He said, ‘Give it a rest. If your eyes were blowtorches she’d never be able to sit down again.’

Then one night, in the yard, I talked to Mickey about it. I just mentioned how I wanted to try my luck. He said he thought I’d do better to steer clear of a girl like that – she was all over the place, she wasn’t for the likes of me. We were filling buckets at the well. Mamma got me to set up running water in the house – she doesn’t know the difference between a mechanic and a plumber. So of course it doesn’t work. It’s a good thing Dad fathered Boo-Boo before he died. He’s the only one who can repair anything. He pours some chemical into the pipes to sort it out – it’s corrosive, like acid. He says they’ll fall apart one day, but it’s OK for the time being. And when it does work you can’t even hear yourself speak.

I told Mickey it was help, not advice, I wanted. We stood there next to the well, with our buckets full of water, for the five thousand years it took him to think about it. My arms were nearly breaking. Finally he said the best way to see her was to go to the dance on Sunday – she was always there.

He meant a portable shack, the Bing Bang, which moved from village to village, and which the local youth followed around the whole region. You bought a ticket when you went in, and you had to pin it on your chest like a deportee. There was nowhere to sit. There were coloured projectors that spun round and round so you couldn’t see anything, and if it was noise you wanted you couldn’t do better for ten francs. Even Cognata could have heard it from outside, and she’d never even realised we had running water.

I said to Mickey that being over thirty in that sort of place, I would look like what I was. He said, ‘Exactly.’ I meant an idiot, but he added, right away, ‘A fireman.’ If I’d had an extra pair of hands I would have carried his bucket for him, anything – you mustn’t overwork a genius like Mickey. I explained to him slowly that what I wanted more than anything else was for her not to see me again on fireman duty. In that case, he said, all I had to do was go in mufti. I gave up. I said I’d see, but Mickey reminded me that there’d be a fireman on duty there in any case, and there’d be a lot of talk at the station about Sergeant Lover Boy. Luckily, no one in our crew ever volunteered for the Bing Bang. To begin with, Sundays were about staying in with the missus, eating a roast, and watching TV. You could say we live in a good place for TV, we can get all the stations, Switzerland, Italy, and Monte Carlo, we can see all the films from way back to the present day. Then if there’s any trouble at the dance – and there’s trouble every time a fourteen-year-old kid feels his moustache growing – a fireman is sent along to stand in for the riot police. One Sunday I had to round up all the men available to go and rescue one of our firemen. He had asked two dancers who wanted the same partner to stop tearing at each other’s shirts. If the police hadn’t arrived before us for once, we’d have been ripped to pieces. As it was, our guy spent three days in the hospital. We had a collection to get him a present when he got out.

At the training session on the Wednesday before the dance, there were only a half-dozen of us. I asked who would come with me to Blumay. It’s a big village fifteen kilometres away, in the mountains, and the Bing Bang was to be set up there the following Sunday. No one volunteered. We went out onto the football field next to the station and did some runs and jumps in our tracksuits. We call it ‘the station’, but it’s really an old copper mine. There are several between the town and the pass. They were closed down in 1914, when they became too expensive to keep open. There’s nothing in ours but weeds and stray cats, but we’ve put in a garage for the two trucks we were allocated, and dressing rooms with a shower. As we were getting dressed, I told Verdier to come with me. He’s a clerk at the post office, doesn’t say much, and is the only single man except me. Anyway, he really likes the job. He wants to take it up professionally. Once he rescued a three-year-old girl, the sole survivor of a pile-up on the other side of the pass. He sobbed when he was told she might die. Since then he’s been hooked. In fact he still writes to the girl, even sends her money. He says when he’s thirty-five he’ll be able to legally adopt her. We joke about it sometimes, because he’s only twenty-five, and by that time she’ll nearly be old enough to marry him.

When I look back to May – especially the days before the Bing Bang – I miss that time. In our part of the world, the winters are terrible, and all the roads are cut off by snowdrifts, but as soon as the fine weather begins, it’s like summer. The days were getting longer, and I worked on the Delahaye well into the evening. Or I worked on Mickey’s two racing bikes – the racing season had begun.

Usually my boss would be there, because he had something to finish off, and after a while his wife, Juliette, brought us pastis. They are both about my age – she went to school with me – but all his hair’s gone white. He comes from the Basque country, and he’s the best boules player I’ve ever seen. In the summer I play with him against the tourists. When there’s an accident or a fire, even in the middle of the night, they telephone the garage – you can’t hear the siren in the village – and he drives me himself, at full speed, to the station. He says the day he took me on to work at the garage he might as well have broken one of his legs.

I still watched Elle ride past during the day, and she still didn’t see me, but I had the feeling that something important was going to happen to me, and it wasn’t just about making love with her. It was like the feeling before our father died, but the opposite, a pleasant feeling.

Yes, it was a good time. Once, as I was leaving the garage after dark, I went up to the top of the pass instead of going home. My excuse was I was going to try out Mickey’s new aluminum bike, but I really wanted to go past Elle’s house. The windows were open, the lamps lit in the downstairs room, but I was too far away to see much – there was a yard in front of the house. I left the bike a little higher up and went around by the cemetery wall. At the back, their house overlooked a field that belonged to Brochard, the café owner. There was just a thorny hedge separating them. When I stood opposite the windows, the first thing I saw was Elle. I got quite a shock. She was sitting at the dining table, under a big ceiling lamp, which had attracted a lot of moths. She was leaning on her elbows and reading a magazine, and as she read, she played with a lock of her hair. I remember she was wearing her little dress with the Russian collar, white with big blue flowers on it. Her face was like I remembered it later, like the dress, younger, more innocent than she looked outside, just because she wasn’t made up.

I stayed there, on the other side of the hedge, just a few metres from her for several minutes. I don’t know how I managed to breathe. Then her father shouted down from upstairs that he was hungry, and her mother answered in German. I realised her mother must be in a corner of the room, out of view. The old fool’s shouting covered up the sound of me leaving. As far as Elle was concerned, he could shout all night – she just went on reading her magazine, fiddling with the same lock of hair.

Of course I laugh at myself when I think about it now. I was stupid. Even when I was a kid and had a crush on a girl – on Juliette, for example, who married my boss and who I used to walk home with after school – I wouldn’t have held my breath behind a hedge to watch someone reading a magazine. I’ve never been the village Romeo, but I’ve had plenty of girlfriends. I’m not counting military service – I was in the navy, stationed at Marseille – because it was no problem then. When we were off duty, we just went out and picked up a girl, and shared her between two or three of us to make it cheaper. But even before that – and especially after – I think I’ve had as many girls as anybody else. Sometimes they’d last for a month, sometimes for a week, or maybe just one night when a festival was on in another village. We’d do it in a vineyard and say we’d see them again, and we never did.

Once I spent over a year with a market gardener’s daughter, Marthe. We were almost at the point of getting married, but she got a job as a teacher near Grenoble, and we wrote to each other less and less. She was blonde and maybe prettier than Elle, though she wasn’t the same type. She was really nice. Anyway, we never saw each other again. She probably married someone else. I see her father occasionally, but he disapproves of me and never says anything.

Just this year, in March and April, just before Elle, I was seeing Louise Loubet, the cashier at the cinema. Everyone calls her Loulou-Lou. She wears glasses but she has a fantastic body. Only men can understand that. She’s tall, and when she’s dressed she’s not bad-looking – not stunning, mind you – but when she takes her clothes off, you don’t know where to put your hands. Unfortunately, her husband’s not much help – he’s Tessari’s boss, and he began to suspect that something was going on, and we had to break it off. She’s desperate to stay in her box office, even though their garage earns them a fortune, just to get out of the house three nights a week and avoid him slobbering all over her. She’s twenty-eight and has her head screwed on. She married him for his money – she doesn’t hide the fact – and she says that what with I-can’t-tonight and Do-everything-to-me-tonight, he’ll end up with a heart attack.

When the film’s over it’s Loulou-Lou’s job to lock the cinema gates – the projectionist says his union won’t let him, and the manager goes off to bed much earlier with the takings. So she’d lock the gates, turn off all the lights except the footlights, so we could at least see what we were doing while I went round the back, so that our affair wouldn’t be splashed all over the newspapers next morning, and she’d let me in. Usually she was already half undressed by this time. We didn’t have much time for talking. We did it in the auditorium, because the manager’s office and the projection room were locked up. We lay down in the main aisle, where there was a carpet, and the first time – I don’t know whether it was because she took me by surprise, or because of those rows and rows of seats around us, and the very high ceiling, and us lying there like idiots in that great space where the slightest sound was magnified – I couldn’t do anything.

Then we tried again on Wednesday night – they have only the one screening, and I came and kept her company at the box office on my way back from the station – and, of course, on Saturday. On Saturday night, Mickey was waiting for me with his truck on the edge of the town. He had a girlfriend, too – a girl who worked with Verdier at the post office. They would just be saying goodbye when I arrived. And sometimes I’d go home alone on my bike, walking the last two kilometres, which are too steep – and what with my lips burning and the cold, deserted road, it felt good.

Finally her husband started to come and pick Loulou-Lou up when she locked the gates, so we had to break up. The night I gave her my helmet to keep, she put a message inside, stuck in the leather band. I found it the next day. It said, ‘You’ll only suffer.’ I didn’t know what she meant, and I didn’t ask her. She meant what Mickey said that day we were filling buckets in the yard. She’d guessed I was ashamed of my helmet and why. She cared about me more than I’d thought. One afternoon last month – I’d better tell everything in the right order – we were alone, with time on our hands, but it was no better than the first time. It was too late.

On Saturday, the night before the dance at Blumay, I called the garage to get them to send somebody to replace me at the cinema. We only send volunteers to the cinema. I think I didn’t want to go so I wouldn’t spoil my chances the next day with Elle. Or else I didn’t want to see her go off after the film in Georges Massigne’s van. Maybe both, I don’t know. Anyway, I regretted not going, I almost had.

As I waited in the kitchen for Mickey and Boo-Boo to come back, I cleaned some parts for the Delahaye which I’d brought in wrapped in a rag. I drank almost a whole bottle of wine. At one point Cognata, who I thought was asleep in her chair, told me not to walk around in circles, it made her feel dizzy. Mamma had gone to bed long before. I also took the opportunity to clean and grease our shotguns – we’d left them in a cupboard since the close of the season. This winter I killed two wild boar, and Mickey one. Boo-Boo shoots only at crows – and then misses them.

It was after midnight when I heard the truck come back and saw its headlights sweep across the windows. They’d been to a Western starring Paul Newman, and they started playing around with the rifles on the table. Cognata laughed and then got scared because she couldn’t hear anything, and Boo-Boo is really good at playing the dying man – bullet in the stomach, eyes crossed, the whole thing. In the end I told Boo-Boo to go and die in his bed, and to help Cognata on his way up – she needs help getting upstairs.

When I was alone with Mickey, I asked him if Elle had been at the cinema. He said yes. I asked him if she’d gone off with Georges Massigne. He said yes, but Eva Braun had been with them. He looked at me as if he expected me to say something else, but I had nothing more to ask – or too much. He put the guns back in the cupboard. I poured him a glass of wine. We talked about Eddy Merckx and our dad, who’d been a good shot in his time. We talked about the singer Marcel Amont. He was going to be on TV the next night. He’s Mickey’s favourite singer. When Marcel Amont is on TV, everything has to stop. We have to listen as if we’re in church. I said Marcel Amont was very good. He said yes he was, what he did was perfect. It’s the big word with him at the moment. Marius Trésor and Eddy Merckx are perfect. Marilyn Monroe is perfect. I said we had to make sure we were back from the dance before the show began. He said nothing.

He’s funny, Mickey. Maybe I sounded hesitant – I went on filling my glass at the same time as his – but it wasn’t only that. He may be thick as pigshit, but you can’t treat him like an idiot for too long – he knows how to hit back. We sat for a while and said nothing. Then he said that all I had to do was stick with him at the dance the next day, and he would fix everything. I said I didn’t need him to get a girl for me – I could look after myself. Then he said something very true. He said, ‘Oh, yes, you do, because you’re interested in her – and I’m not.’

That fateful Sunday began with all three of us showering in the yard. There was bright sunshine, and we made fun of Boo-Boo, who never wants to show his cock, and who yells and screams and wraps himself in the flowery curtain I’ve set up. The spring water is cold all summer. Your heart almost stops when it first hits you. We use a handpump to get it up into a cistern and it flows out really well. Once you’re used to it, it feels like a proper modern shower. Mickey went off to town to place our bets – on his bike, to keep in training – and when he came back, I’d dressed completely differently from how I usually do. At lunch they all stared at me a bit oddly – they’d never seen me wearing a tie before.

Verdier was going to pick me up in Blumay in the fire-station Renault. The five of us – Boo-Boo and Mickey’s girlfriend, Georgette, were also coming with us – went in my boss’s Citroën DS. He always lends it to me when I ask, but every time I return it he says it’s not running as well as before. Verdier couldn’t get over seeing me out of uniform. I was in my brown suit, a pink shirt and one of Mickey’s red knitted ties. I explained I was with my brothers, I hadn’t had time to change into uniform, but if anything happened, my things were in the car.

It was three o’clock, and there was already incredibly loud music coming from the Bing Bang, which had been set up in the square. People crammed themselves into the entrance of the huge shack, just to have a look – then they stayed there for the rest of the afternoon. I told Verdier to stay on duty at the cash desk, and to make sure everybody put their cigarettes out when they came in. He didn’t argue. He never does.

They know me. They didn’t want me to pay to go in, but I insisted; I wanted to have a ticket pinned on me like everyone else. It was hell inside, what with the red lighting and the ear-splitting noise made by the band. You couldn’t see or hear anybody, and the sun was beating down on the corrugated roof, so we were all suffocating in the heat. Boo-Boo went off to look for his mates. Then Mickey pushed me towards Georgette so that I’d dance with her, and he went off, too, into the shadows milling around us. Georgette started rolling her head and wiggling her arse, and so did I. The only area that was properly lit was the little round stage, where the band was letting rip. They were five young guys in fringed trousers, their faces and torsos painted in rainbow stripes. Later Boo-Boo told me they were called the Apaches and were very good.

Anyway, I kept on dancing in the bit of space I had, with Georgette, as one number went into the next. I was covered in sweat. I really thought it would never end; then suddenly the projectors stopped, the lighting almost went back to normal, and the Apaches, who were exhausted by now, strummed a slow number. I saw boys and girls sitting down on the ground by the shack partition, with their hair sticking to their faces. Then I caught sight of Mickey – he’d found Elle. As I’d feared, she was with Georges Massigne, but I didn’t really care, that’s just how it goes.

She had on a white dress made of very thin material. Her hair was plastered down on her forehead, and from where I stood, fifteen or twenty steps away, I could see her chest rising and falling, her lips wide open, gasping for breath. I know it’s stupid, but she turned me on so much I felt ashamed, or scared, I don’t know which. Anyway, I almost left. Mickey was talking to Georges. I knew what he was up to. He’d be making up some story to get Georges out of there and leave the field clear for me. He gestured to me. He said something to Elle, and she looked over towards me. She looked at me for several seconds, without moving her head, without turning her eyes away. I didn’t even notice that Mickey had left with Georges Massigne.

Then she went over to some other girls – two or three who lived in the village – and they started laughing. I thought they were laughing at me. Georgette asked me if I wanted to dance again; I said no. I took off my jacket and tie, and looked for somewhere to put them. Georgette said she’d look after them for me, and when I turned around, with my hands free and my shirt sticking to my back, Elle was there, in front of me. She wasn’t smiling, just waiting and – I knew. You always do.

I had one dance with her, then another. I can’t remember what the song was – I’m a good dancer though I never really pay attention to the music – but it must have been something slow, because I was holding her in my arms. Her hand was clammy. She kept wiping it on the back of her dress, and I could feel the heat of her body through the material. I asked her what she’d been laughing about with her friends. She tossed back her long dark hair, brushing my cheek with it, but she didn’t avoid the question. The first thing she said nearly knocked me over. She had been laughing with her friends because she hadn’t really wanted to dance with me and, without meaning to, had said something hilarious about the fireman and his pump. No kidding.