Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

Dany Longo is blonde, beautiful - and thoroughly unpredictable. After doing a favour for her boss, she finds herself behind the wheel of his exquisite Thunderbird on a sun-kissed Parisian morning. On impulse she decides to head south.What starts as an impromptu joy-ride rapidly becomes a nightmare when strangers all along the unfamiliar route swear they recognise Dany from the previous day. But that's impossible: she was at work, she was in Paris, she was miles away . . . wasn't she?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 402

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Sébastien Japrisot was a prominent French author, screenwriter and film director, and the French translator of J. D. Salinger. He is best known for A Very Long Engagement, which won the Prix Interallié and was made into a film by Amélie director Jean-Pierre Jeunet. One Deadly Summer won the Prix Deux Magots in 1978 and the film adaptation starring Isabelle Adjani won the César Award 1984. Born in Marseille in 1931, he died in 2003.

Helen Weaver is an American writer and translator. She has translated more than fifty books from French. Antonin Artaud: Selected Writings was a Finalist for the National Book Award in translation in 1977.

Christian House is an arts journalist and literary critic.

Praise for One Deadly Summer:

‘The most welcome talent since the early Simenons’

New York Times

‘A gripping tale of hatred, revenge, and lust … A sinister spellbinder’

Publishers Weekly

‘Japrisot’s talent lies for one part in the clever construction of his novels that mimics a game of Meccano, each piece slotting neatly, one into another. Of course, it also lies in the writing that is simple, rhythmical, surprising, phonetic and lyrical’

Le Point

‘Sébastien Japrisot holds a unique place in contemporary French fiction. With the quality and originality of his writing, he has hugely contributed to breaking down the barrier between crime fiction and literary fiction’

Le Monde

‘Unreeled with the taut, confident shaping of a grand master … Funny, awful, first-rate. In other hands, this sexual melodrama might have come across as both contrived and lurid; here, however, it’s a rich and resonant sonata in black, astutely suspended between mythic tragedy and the grubby pathos of nagging everyday life’

Kirkus Reviews

Praise for A Very Long Engagement:

‘A classic of its kind, brewing up enormous pathos undiluted by sentimentality’

The Telegraph

‘The narrative is brilliantly complex and beguiling, and the climax devastating’

The Independent

‘Riveting … A fierce, elliptical novel that’s both a gripping philosophical thriller and a highly moving meditation on the emotional consequences of war’

New York Times

‘Diabolically clever … The reader is alternately impressed, beguiled, frightened, bewildered’

Anita Brookner, Man Booker-winning author of Hotel du Lac

‘A kind of latter-day War and Peace … A rich and most original panorama’

Los Angeles Book Review

‘Precisely, surprisingly evocative of the lingering pain of mourning and the burdens of survival’

Kirkus Reviews

Also available from Gallic Books:

One Deadly Summer

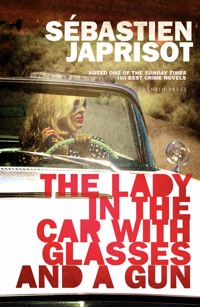

The Lady in the Car with Glasses and a Gun

The Lady in the Car with Glasses and a Gun

SÉBASTIEN JAPRISOT

Translated from the French by Helen Weaver

Adapted by Gallic Books

Introduction by Christian House

Pushkin Press

A Gallic Book

First published in France as La dame dans l’auto avec des lunettes et un fusilby Éditions Denoël, 1966

Copyright © Éditions Denoël, 1966

English translation copyright © Souvenir Press, 1967

First published in Great Britain in 1968 by Souvenir Press

Introduction © Christian House, 2019

This edition first published in 2019 by

Gallic Books, 59 Ebury Street,

London, SW1W 0NZ

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention

No reproduction without permission

All rights reserved

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologises for any errors or omissions and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781805334248

Typeset in Adobe Garamond by Palimpsest Book Production Ltd, Falkirk, Stirlingshire

Printed in the UK by CPI (CR0 4YY)

Contents

Introduction

The Lady

The Car

The Glasses

The Gun

Introduction

Sébastien Japrisot liked to break mirrors. The French novelist created characters that don’t recognise themselves. They are amnesiacs, dupes and doppelgängers, they are the deluded and deceived. ‘She was living, fully awake, in a dream,’ observes one. ‘I don’t know what I’m saying half the time,’ confesses another. Hoodwinking the reader is one thing but keeping one’s narrator in the dark is a trickier sleight of hand. Welcome to Japrisot’s opaque world.

Like many British readers, I discovered the author through the English translation of his 1991 anti-war classic, A Very Long Engagement (Un long dimanche de fiançailles). It’s a rare novel that manages to be – simultaneously – a gripping detective story, a relentless account of the horrors of the First World War and an exploration of the notion of evidence. It is also a great love story.

The novel’s heroine, Mathilde Donnay, is a typical Japrisot creation. Searching for her lost fiancé, presumed killed on the Western Front, the irrepressible Mathilde investigates events in the trenches, analysing the subjective accounts of witnesses and the equally unreliable official reports. It’s a jigsaw puzzle. As with much of Japrisot’s writing, the narrative is shaped by providence. ‘Once upon a time there were five French soldiers who had gone off to war,’ reads the opening line. ‘Because that’s the way of the world.’

The way of the world, in all its tragic and hopeful guises, was to be the author’s preoccupation throughout a prolific and varied career – one that spanned literary fiction, crime novels, screenplays and translations, right up to his death in March 2003. He had a Graham Greene-like reputation in France: a brilliant talent cocooned in a complicated and volatile personality. However, on this side of the Channel, he has remained relatively obscure to all but Francophiles and cineastes.

Japrisot was born Jean-Baptiste Rossi in Marseille in 1931 into a family of Neapolitan immigrants. The toughness of those two cities, forged by crime and a hard-living itinerant working class, would bleed into his work. His thrillers were often set in the seamier corners of the Côte d’Azur and peopled with men on the make and women making do.

A born rebel, in his youth Japrisot disregarded authority at every turn. He was expelled from his Jesuit school and moved to the Sorbonne to study philosophy, where he ignored his teachers, using lectures to write fiction. The result of those wayward years would be his shocking debut novel, The False Start (Les mal partis). Published when the writer was only seventeen, the book chronicled a love affair between a schoolboy and a nun. It was a tremendous hit both in France and abroad, selling some 800,000 copies in America in just three weeks.

Early notoriety brought him to that iconic figure of disaffected youth, Holden Caulfield. At twenty, Japrisot landed the job of translating The Catcher in the Rye into French. He took other translating commissions and worked for periods in advertising and publicity. When he returned to his own fiction, in the early 1960s, he employed the anagrammatical tag of Japrisot and with it embraced a strange hybrid of police procedural, psychological study and social commentary. It proved to be a gritty yet dream-like combination.

Japrisot wrote his first two crime novels in a month. The 10.30 from Marseille (Compartiment tueurs) took the locked-room mystery beloved of Christie and Conan Doyle and reconfigured it for the grimy confines of a French railway carriage, while Trap for Cinderella (Piège pour Cendrillon) was an ingenious and bitter fairy tale in which a fire at a Riviera villa leaves a young heiress unrecognisable from burns. Or is she the housekeeper’s daughter, a poor cuckoo in the gilded nest? No one knows, least of all the girl.

Both books appeared in 1962. Short, sharp and clever, they won him the Grand Prix de Littérature Policière and comparisons with Georges Simenon. It was a fitting reference point: Japrisot’s bedroom was lined with the works of Maigret’s creator.

More enigmas were to follow. In 1966 he published The Lady in the Car with Glasses and a Gun – possibly my favourite title of any novel – which details a road trip fuelled by torment. Its heroine, Dany, is a put-upon secretary who takes her boss’s white Thunderbird on a joy-ride from Paris to the south of France. En route things turn upside down: Dany is recognised by people she doesn’t know and is told she has visited places she has never been. It’s a riddle as captivating as it is terrifying. And, again, it illustrated the author’s fondness for a perplexed protagonist.

The promise – or threat – of sex is never far from the surface in a Japrisot story. His men are brutal, his women brutalised. In One Deadly Summer (L’été meutrier) a young man is driven witless by the erotic manipulations of a Provençal femme fatale in a scenario that presents sex as both crime and punishment. Japrisot almost always wrote from a female viewpoint.

He turned that novel into a screenplay (making a star out of Isabelle Adjani in the process). He saw the mechanics of cinema and literature as interchangeable: he made the page widescreen and his films as considered as his written works. He also brought other writers’ work to the screen, such as Pauline Réage’s notorious The Story of O, and briefly tried his hand at directing.

A list of the stars in his film projects – Alain Delon, Yves Montand, Michel Piccoli, Audrey Tautou – reads like a who’s who of French cinema. But when English-speaking actors were required it was the coarse talents of Oliver Reed and Charles Bronson that were called upon, rather than the matinee idols.

He cultivated a reputation as a tough guy himself. There were claims that he was impossible to work with. His French publisher at Denoël insisted on accompanying him to London for a book tour just to keep him in line. In the end he behaved like an angel. Here was a sheep in wolf’s clothing; a reversal that is reflected in his stories. While cloaked in intrigue and peppered with violence, their real subject is the indomitable human spirit. He was as much a romantic – albeit a fatalistic one – as he was a purveyor of hard-boiled crime.

The author never reaped the rewards created by the slow-burn success of A Very Long Engagement and its subsequent film adaptation. Japrisot faded out with the twentieth century, as the effects of drink and his favoured Gauloises took their toll. ‘Treat everything with derision,’ he said with rancour in one of his last interviews. ‘It’s the only way to counter misfortune.’ His final novel remained unfinished.

And yet, however unlikely it might seem, there remains something buoyant about Japrisot’s cracked mysteries. Love is resilient, the hurt heal, clarity is found. The broken mirrors are put back together again.

Christian House, 2019

The Lady

I have never seen the sea.

The black-and-white tiled floor sways like water a few inches from my eyes.

It hurts so much I could die.

I am not dead.

When they attacked me – I’m not crazy, someone or something attacked me – I thought, I’ve never seen the sea. For hours I had been afraid: afraid of being arrested, afraid of everything, I had made up a whole lot of stupid excuses and it was the the stupidest one that crossed my mind: Don’t hurt me, I’m not really bad, I wanted to see the sea.

I also know that I screamed, screamed with all my might, but that my screams remained trapped in my throat. Someone lifted me off the ground, someone smothered me.

Screaming, screaming, screaming, I thought again, It’s not real, it’s a nightmare, I’m going to wake up in my room, it will be morning.

And then this.

Louder than all my screams, I heard it: the cracking of the bones of my own hand, my hand being crushed.

Pain is not black, it is red. It is a well of blinding light that exists only in your mind. But you fall into it all the same.

Cool, the tiles against my forehead. I must have fainted again.

Don’t move. Above all, don’t move.

I am not lying flat on the floor. I am kneeling with the furnace of my left arm against my stomach, bent double with the pain which I would like to contain and which invades my shoulders, the nape of my neck, my back.

Right near my eye, through the curtain of my fallen hair, an ant moves across a white tile. Further off, a grey, vertical shape, which must be the pipe of the washbasin.

I don’t remember taking off my glasses. They must have fallen off when I was pulled backwards – I am not crazy, someone or something pulled me backwards and stifled my screams. I must find my glasses.

How long have I been like this, on my knees in this tiny room, plunged into semi-darkness? Several hours or a few seconds? I have never fainted in my life. It is less than a hole, it is only a scratch in my memory.

If I had been here for very long someone outside would have become worried. I was standing in front of the sink, washing my hands. My right hand, when I hold it against my cheek, is still damp.

I must find my glasses, I must get up.

When I raise my head quickly – too quickly – the tiles spin, I am afraid I will faint again, but everything subsides, the buzzing in my ears and even the pain. It all flows back into my left hand, which I do not look at but which feels like lead, swollen out of all proportion.

Hang on to the basin with my right hand, get up.

On my feet, my blurred image moving with me in the mirror opposite, I feel as if time is starting to flow again.

I know where I am: the toilets of a service station on the Avallon road. I know who I am: an idiot who is running away from the police, a face towards which I lean my face almost close enough to touch, a hand which hurts and which I bring up to eye level so I can see it, a tear which runs down my cheek and falls onto this hand, the sound of someone breathing in a strangely silent world: myself.

Near the mirror in which I see myself is a ledge where I left my handbag when I came in. It is still there.

I open it with my right hand and my teeth. I look for my second pair of glasses, the ones I wear for typing.

Clearly visible now, my face in the mirror is smudged with dust, tear-stained, tense with fear.

I no longer dare look at my left hand, I hold it against my body, pressed against my badly soiled white suit.

The door of the room is closed. But I left it open behind me when I came in.

I am not crazy. I stopped the car. I asked them to fill the tank. I wanted to run a comb through my hair and wash my hands. They pointed to a building with white walls behind the station. Inside it was too dark for me, so I did not shut the door. I don’t know now whether it happened right away, whether I had time to fix my hair. All I remember is that I turned on the tap, that the water was cool – oh, yes, I did do my hair, I’m sure of it! – and suddenly there was a kind of movement, a presence, as of something alive and brutal behind me. I was lifted off the floor, I screamed with all my might without making a sound, I did not have time to understand what was happening to me, the pain that pierced my hand shot through my whole body. I was on my knees, I was alone, I am here.

Open my bag again.

My money is there, in the envelope with the office letterhead. They didn’t take anything.

It’s absurd, it’s impossible.

I count the notes, lose track, start again. A cold shadow passes over my heart; they didn’t want to take my money or anything else, all they wanted – I am crazy, I will go crazy – was to hurt my hand.

I look at my left hand, my huge purple fingers, and suddenly I can’t stand it any more, I collapse against the basin, fall to my knees again and howl. I will howl like an animal until the end of time, I will howl, weep and stamp my feet until someone comes, until I see daylight again.

Outside I hear hurried footsteps, voices, gravel crunching.

I howl.

The door opens very suddenly onto a dazzling world.

The July sun has not moved over the hills. The men who come in and lean over me, all talking at once, are the ones I passed when I got out of the car. I recognise the owner of the garage and two customers who must be local people who had also stopped for petrol.

While they are helping me to my feet, through my sobs my mind fastens on a silly detail: the tap in the basin is still running. A moment ago I didn’t even hear it. I want to turn the tap off, I must turn it off.

The men don’t understand why I have to do that. Nor do they understand that I don’t know how long I have been here. Nor that I have two pairs of glasses. As they hand me the pair that fell off, I keep repeating that they are mine, they really are mine. They say, ‘Calm yourself, come now, calm yourself.’ They think I am crazy.

Outside, everything is so clear, so peaceful, so very real that my tears suddenly stop. It’s an ordinary petrol station like any other. With pumps, gravel, white walls, a gaudy poster pasted to a window, a hedge of spindle and oleander. Six o’clock on a summer evening. How could I have screamed and rolled on the floor?

The car is where I left it. Seeing it reawakens my old anxiety, the anxiety that had hold of me when it happened. They’re going to question me, ask me where I am from, what I have done, I will answer all wrong, they will guess my secret.

In the doorway of the office towards which they lead me a woman in a blue apron and a little girl of six or seven are watching me with curious, interested faces, as if at the theatre.

Yesterday afternoon, too, at the same time, a little girl with long hair and a doll in her arms watched me approach. And yesterday afternoon, too, I was ashamed. I can’t remember why.

Yes, I can. Quite clearly. I can’t stand children’s eyes. Behind me there is always the little girl I was, watching me.

The sea.

If things go badly, if I am arrested and must provide a – what is the word? – an alibi, an explanation, I will have to begin with the sea.

It won’t be altogether the truth, but I will talk for a long time without catching my breath, half crying, I will be the naïve victim of a cheap dream. I’ll make up whatever I need to make it more real: attacks of split personality, alcoholic grandparents, or that I fell down the stairs as a child. I want to nauseate the people who interrogate me, I want to drown them in a torrent of syrupy nonsense.

I’ll tell them I didn’t know what I was doing, it was me and it wasn’t me, understand? I thought it would be a good opportunity to see the sea. It’s the other one who’s guilty.

They will answer, of course, that if I was so anxious to see the sea, I could have done it a long time ago. All I had to do was buy a train ticket and book a room at Palavas-les-Flots, other girls have done it and not died of it, there is such a thing as paid holiday.

I’ll tell them that I often wanted to do it but that I couldn’t.

Which is true. Every summer for the past six years I’ve written to tourist offices and hotels, received brochures, stopped in front of shop windows to look at bathing suits. One time I came within an inch – in the end, my finger refused to press a buzzer – of joining a holiday club. Two weeks on a beach in the Balearics, round-trip fare and visit to Palma included, orchestra, swimming teacher and sailing boat reserved for the duration of the visit, good weather guaranteed by Union-Life, and I don’t know what else. Just reading the description gave you a tan. But, for some unknown reason, every summer I spend half my vacation at the Hotel Principal (there is only one) of Montbriand in the Haute Loire, and the other half near Compiègne at the home of a former classmate who has a husband, you know, and a deaf mother-in-law. We play bridge.

It’s not that I am such a creature of habit or that I have a passion for card games. And it’s not that I am particularly shy. As a matter of fact, it takes a lot of nerve to relate memories of the sea and St Tropez to your colleagues when you are fresh from the forest of Compiègne. So I can’t explain it.

I hate people who have seen the sea, I hate people who haven’t seen it, I think I hate the whole world. There you are. I think I hate myself. If that explains it, all well and good.

My name is Dany Longo. Marie Virginie Longo, to be exact. I made up Danielle when I was a child. I have lied all my life. Now I wouldn’t mind Virginie, but it would be hard to explain.

My legal age is twenty-six, my mental age eleven or twelve, I am five feet six inches tall, I have dirty blond hair which I dye once a month with hydrogen peroxide, I am not ugly but I wear glasses – with tinted lenses, darling, so that no one will realise I am short-sighted – but everyone does, stupid – and the thing I am best at is keeping my mouth shut.

I have never said anything to anyone but Please pass the salt. Except twice and both times I suffered. I hate people who don’t understand the first time you slap their hands. I hate myself.

I was born in a village in Flanders of which I remember only the smell of the coal mixed with mud which the women were allowed to gather near the mines. My father, an Italian refugee who worked at the railway station, died when I was two years old. He was run over by a train from which he had just stolen a box of safety pins. Since it’s from him that I inherited my short-sightedness, I assume that he had misread what was printed on it.

This happened during the Occupation, and the convoy was on its way to the German army. A few years later my father was rehabilitated in a way. As a memento of him I still have somewhere in my chest of drawers a silver or silver-plated medal embossed with the image of a slender girl breaking her chains like a carnival strongman. Every time I see a strongman performing on the pavement I think of my father, I can’t help it.

But there are other heroes in my family. At the Liberation, less than two years after the death of her husband, my mother jumped out of a window of our town hall just after her head had been shaved. I have nothing to remember her by. If I tell someone this one day I will add: not even a lock of her hair. If they give me a horrified look, I don’t care.

I had seen her only two or three times in two years, poor girl, in the visiting room of an orphanage. I couldn’t possibly tell you what she was like. Poor, and looking it, probably. She came from Italy too. Her name was Renata Castellani. Born in San Appollinare, province of Frosinone. She was twenty-four when she died. I have a mother younger than I am now.

I read all this on my birth certificate. The sisters who brought me up always refused to tell me about my mother. When I finished school and was set free, I returned to the village where we used to live. I was shown the part of the cemetery where she was buried. I wanted to save up and do something, buy her a tombstone, but there were other people with her, they wouldn’t let me.

Well, I don’t give a damn.

I worked for a few months in Le Mans as a secretary in a toy factory, then in Noyon for a solicitor. I was twenty when I found a job in Paris. I now earn 1,270 francs a month, after tax, for typing, filing, answering the telephone and occasionally emptying the waste-paper baskets in an advertising agency with a staff of twenty-eight.

On this salary I can have steak for lunch and yoghurt and jam for dinner, dress just about the way I like, rent a one-bed on Rue de Grenelle, and improve my mind twice a week with Marie-Claire, and every night with a widescreen TV set on which I only have three more payments to make. I sleep well, don’t drink, smoke in moderation, have had a few affairs, but not the kind that would shock the landlady, I don’t have a landlady but I do have the respect of the people down the hall, I am free, without responsibilities and utterly miserable.

Those who know me – the layout men at the agency or the woman who sells me groceries – would probably be amazed to hear me complain. But I must complain. I realised before I learned to walk that if I didn’t do it, no one would do it for me.

*

Yesterday afternoon, Friday, 10 July. It seems like a century ago, another life.

It couldn’t have been more than an hour before the agency closed. The agency occupies two floors of what was until recently a private house, all volutes and colonnades, near the Trocadéro. It is still full of crystal chandeliers that tinkle with every breath of air, marble fireplaces, and tarnished mirrors. My office is on the second floor.

There was sunlight beating on the window behind me and on the papers that covered my desk. I had checked the plan for the Frosey campaign (the eau de toilette that is fresh as dew), spent twenty minutes on the phone trying to get a weekly magazine to lower the price of a badly printed ad, and typed two letters. A little earlier I had gone out as usual for a cup of coffee at the nearby coffee bar with two copy girls and a pretty boy from ad space. He was the one who had asked me to call about the botched ad. When he handles it himself he lets them get away with murder.

It was an ordinary afternoon, and yet not completely so. At the studio the draughtsmen were talking about cars and Kiki Caron, lazy girls were coming into my office to pinch cigarettes, the assistant to the assistant to the boss, who works hard at trying to seem indispensable, was braying in the hall. There was nothing to distinguish that day from other days, but everyone exuded that impatience, that suppressed jubilation which precedes long weekends.

Since Bastille Day fell on a Tuesday this year, it had been understood since at least January (that is, the time when we received our schedules) that we would be given a four-day holiday. To make up for the lost Monday we worked two Saturday mornings when nobody was on holiday except me. I took my holiday in June. Not to accommodate someone else who wanted to take their holiday in July, but because, unbelievable as it may seem, even the Hotel Principal of Montbriand in the Haute Loire was full for the rest of the season. People are crazy.

This, too, will have to be explained if I am arrested: my return from an alleged Mediterranean holiday, well tanned (I bought myself an ultraviolet lamp for my birthday, 180 francs, they say they give you cancer but I don’t give a damn), to a bunch of excited people who were getting ready to leave. For me it was over, kaput, until the eternity of next year, and as far as I am concerned my holiday has at least this advantage, that I can put it out of my mind simply by crossing the threshold of my office. But this time they all did their best to prolong my agony.

The boys always went to Yugoslavia. I don’t know how they manage but they sell things to the Yugoslavians and always seem to make money there. They say that it’s not that much, but that you don’t need much to live like a king there even if you take your wife, your wife’s sister and all her kids. There are magnificent beaches and if you’re clever about going through customs, you can even bring back souvenirs – alcohol, or a pitchfork you can use as a hatstand. I was sick of hearing about Yugoslavia.

With the girls it was Cap d’Antibes. If you go there, come and see me, I have a friend with a swimming pool, he puts a special liquid in it for the density of the water, even if you’re a terrible swimmer you can’t help but float. In their lunch hour they would comb the department stores with a sandwich in one hand and their July bonus in the other. I would see them come back to the office with eyes that were already looking at the sea, flushed from running and dishevelled from raiding the bargain counters, their arms loaded with their finds: a nylon dancing dress that folds up as small as a pack of cigarettes or a Japanese transistor with a built-in tape recorder, you can record all the songs on Europe 1 as they are broadcast, two free tapes as a bonus and you can use the bag as a beach bag, when it’s filled it becomes a pillow. What do you bet that one afternoon one of them will call me into the loos to ask my opinion of her new bathing suit.

I celebrated my twenty-sixth birthday on 4 July, last Saturday, after the excitement of the Grand Départ of the Tour. I stayed home, I did a little housework, I didn’t see anyone. I felt old, left out, sad, short-sighted, and stupid. And too jealous to live. Even when you think you’ve stopped believing in God, to be that jealous must be a sin.

Yesterday evening things were not much better. There was the prospect of the interminable weekend for which I had no plans, and also – even worse – there were the plans of the others, which I heard from the next offices, partly because their voices are loud, partly because I am a miserable masochist and was listening.

Other people always have plans. I don’t know how to plan, I always call at the last minute and nine times out of ten people don’t answer or they have something else to do. Worse still was the one time I did arrange a dinner at my place with a woman journalist whom I knew from work and a rather well-known actor who was her lover, plus a draughtsman from the agency so I wouldn’t look too stupid. We made the date two weeks in advance, I wrote it down in my diary but when they arrived I had forgotten all about it, all I had to give them was yoghurt and jam. We went out to a Chinese restaurant and I had to make a big fuss just to get them to let me pay the bill.

I don’t know why I am like that. Maybe because for the first eighteen years of my life I never had to think for myself. My plans for holidays or for Sundays were made for me, and they were always the same: I would repaint the chapel with other girls who, like me, had nobody outside the orphanage (I love to paint anyway), or hang around the deserted playgrounds with a ball under my arm. Sometimes I was taken to Roubaix where Mama Supe, our Mother Superior, had a brother who was a pharmacist. I would stay for a few days, minding the till, they would give me a dose of tonic before every meal, then Mama Supe would come and get me.

When I was sixteen, during one of those trips to Roubaix, I did or said something that made her sad – I don’t remember what, it wasn’t important – and at the last moment she decided that we would miss the train that was to take us back. She treated me to shellfish in a brasserie and we went to the cinema. We saw SunsetBoulevard. When we came out Mama Supe was sick with shame. She had chosen this film because she cherished an enduring memory of Gloria Swanson as a pure young girl; she certainly did not suspect that in less than two hours there would parade before my eyes all the depravity that they had always tried to conceal from me.

I cried, too, on the way to the station (we had to run like mad to catch the last train), but I was not crying from shame. I was crying in wonder. I was in the throes of a delicious sadness, I was breathless with love. It was the first film I had ever seen and the best in my whole life. When she fires at William Holden and he staggers to the swimming pool, when Erich von Stroheim directs the cameras of the newsreels and she walks down the stairs thinking she’s creating a new role, I thought I would die right there, on my seat, in a cinema in Roubaix. I can’t explain it. I was in love with them, I wanted to be them, all three of them, Holden, Stroheim and Gloria Swanson. I even loved Holden’s little girlfriend. When they walked through the scenery of the empty studio, I longed desperately to live inside that story. I wished it would play again, endlessly, and that I would never have to leave it again.

To console herself on the train Mama Supe kept repeating that, thank God, the worst of this web of aberrations was merely implied, that it was too deep for her, so I certainly would not have been able to understand it. But I have seen the film again several times since I came to Paris and I know that the first time essentially nothing escaped me.

Yesterday afternoon, as I was sealing the two letters I had just typed, I thought I might go to the cinema. This is probably what I would have done if I had a tenth of the good sense that is attributed to me on my best days – and that isn’t saying very much. I would have picked up the phone a few hours in advance, for a change, and I would have found someone to accompany me. After that, I know myself: a hydrogen bomb falling on Paris would not have kept me away, and none of this would have happened.

And yet, who knows? The truth is that yesterday, today, or six months from now, something like this would have happened to me anyway. I am jinxed.

I did not pick up the phone. I lit a cigarette and I took my two letters to the mail basket in the hall. Then I went down to the floor below. I spent a few minutes in the storeroom where newspapers (referred to pompously as ‘documentation’) are filed. Georgette, the girl in charge, was cutting out advertisements with her tongue sticking out. I looked at the cinema programmes in that morning’s Figaro, but found nothing that appealed to me.

When I went back up to my office the boss was waiting for me. When I opened the door and found him standing there in a room which I had thought empty, my heart jumped.

He is a man of forty-five or so, rather tall, and he weighs over fourteen stone. His hair is cut short, very close to the head. His features are coarse but pleasant, and they say that when he was younger and slimmer he was handsome. His name is Michel Caravaille. It was he who set up the agency. He has a talent for advertising, he knows how to explain exactly what he wants, and in a business where it is just as important to convince the client who pays us as the buying public, he is a first-rate salesman.

His relations with and interest in the staff are limited to business. Personally, I hardly know him. I see him only once a week, Monday morning at a half-hour meeting in his office when he goes over current business. I am only there to take notes.

Three years ago he married Anita, a girl my age whose secretary I was in another advertising agency. We were friends. That is, as much as you can be when you spend forty hours a week in the same office, have lunch together every day in a cafeteria in Rue La Boétie, and sometimes meet on Saturday to go to the music hall.

When they got married it was she who suggested that I come and work for Caravaille. She had been working there for a few months. I do just about what she did, minus her talent, which was considerable, her hunger for success, or, obviously, her salary. I have never met anyone who was so desperately and selfishly eager to get ahead. She worked on the principle that in a world where most people learn to bend before a storm, you must create storms in order to walk over them. They called her Anita-Screw-You. She knew it and she signed her memoranda that way when she was letting somebody have it.

About three weeks after her marriage she had a little girl. After that she stopped working, and I hardly ever saw her. As for Michel Caravaille, I thought (until yesterday afternoon, that is) that he had even forgotten I knew his wife.

He looked tired or preoccupied, with that sallow look he sometimes gets when he has been on a reducing diet for a few days. He called me Dany and said he had a problem.

I saw that there were some files piled on the visitor’s chair facing my desk. I removed them, but he did not sit down. He was looking around as if he had come into my office for the first time.

He said he was taking a plane to Switzerland the next day. We have an important client in Geneva: Milkaby, powdered milk for babies. To sell the next campaign he could take along layouts, sample prints on glossy paper, colour photographs – enough material to hold his own respectably for an hour or two with a dozen directors and subdirectors with frozen faces and manicured gestures. But the accompanying literature was not ready. Soberly he explained (if I’ve heard this kind of explanation once, I’ve heard it a hundred times) that a whole report had been drafted on the competition’s strategy and our own, but that at the last moment he had had to change everything, that it was in very rough form, and that for all intents and purposes he no longer had anything to show.

He spoke quickly without looking at me, because he was embarrassed to have to ask me a favour. He said he couldn’t leave empty-handed. Nor could he put off his meeting with Milkaby; he had already done it twice. The third time even the Swiss would realise that we were a bunch of idiots and that they would be better off giving their milk away for free than paying us to help them to sell it.

I had a fair idea what he was driving at, but I didn’t say anything. There was a silence during which he played unconsciously with one of the tiny toys lined up on my desk. I had sat down. I lit another cigarette. I pointed to my pack of Gitanes, but he did not want one.

At last he asked me whether I had plans for the evening. He often talks this way, in a sophisticated and slightly insulting manner. I think he is incapable of imagining that I could do anything at all with my evenings except sleep, so as to be fresh for the office the next day. Poor idiot that I was, I didn’t know what I wanted to do, and in a voice that tried to be disinterested I asked, ‘How many pages need to be typed?’

‘Around fifty.’

I exhaled the smoke I had in my mouth in a pretty, reproachful cloud, all the while thinking (which spoiled everything), You exhale like a film star, he’ll see that you’re trying to make an impression.

‘And you want me to do it this evening? But I won’t manage that! I do six pages an hour, and that is top speed. Ask Madame Blondeau, she might be able to get it done.’

He told me that his plane did not leave until noon. And there was no question of entrusting this job to Madame Blondeau. She typed quickly but would not be up to a text full of corrections, cross references, and incomplete sentences. I was familiar with the material.

Then he said – and I think that this is what decided me – that he did not like, he never liked, anyone to stay at the office after hours, especially for a long stint of typing. There are people living on the upper floors, and the agency retains its lease only by tricky administrative negotiations. He told me that I would come and work at his place. I could sleep over, that way I would not waste any time if I did not finish that evening. I would finish the job the next morning, before he left.

I had never been to his place. This and the prospect of seeing Anita again made it impossible for me to refuse. For a second or two, while he fidgeted and said, Good, it’s all settled, I don’t know what I imagined. I am an idiot: the three of us at dinner, in a big room with soft lights. Muted laughter as we talked about old times. Have some more crab, do! Anita leads me by the hand to my room, a little mellow and sentimental from the wine we have drunk. A window is open to the night and the curtains swell in the breeze.

He brought me down to earth immediately. Looking at his watch, he said that I could work undisturbed, since his servants had gone back to Spain for the holidays, and he and Anita had a tiresome function to attend, a festival of commercials at the Palais de Chaillot. He added, however, ‘Anita will be happy to see you again. You were her protégée in a way, weren’t you?’

But he said it without looking at me, walking to the door, exactly as if I did not exist, not as a human being, anyway – no more than an IBM electric typewriter with ‘Presidential’ typeface.

Before leaving he turned around and gestured vaguely towards my desk. He asked if I had anything important still to do. I was planning to read the proofs of an industrial brochure, but that could wait, and for once I said the right thing: ‘Collect my pay.’

I was talking about the extra month’s pay which we are given half in December, half in July. Those who are on holiday received their bonus with their June pay. The others receive it for the Fourteenth of July. As at the end of the month, it is the head bookkeeper who goes through the office and hands the envelope to everyone personally. He usually comes to my office within half an hour of closing. First he goes to copywriting where he unleashes a kind of cataclysm, but yesterday afternoon I had still not heard the copy girls pouncing on the poor man.

The boss stood motionless with his hand on the doorknob. He announced that he was going home and that he would like to take me with him right away. He would give me my envelope himself, which would give him the opportunity to add something to it, say three hundred francs, if that was agreeable to me.

There was a kind of relief in his look, and of course I was pleased too, but for him it was fleeting, as if I had simply made it possible for him to settle an embarrassing matter.

‘Get your things, Dany. I’ll meet you downstairs in five minutes. My car is outside.’

He left, closing the door behind him. Almost immediately he opened it again. I was putting the toy he had moved back in line with the others. It was a little hinged elephant, candy pink. Noticing the care with which I did this, he said, ‘I apologise.’ He said he was counting on me to say nothing to the others about this work outside the office. I understood that he did not want me to talk about the late report, that he felt a little guilty. He wanted to say something else, maybe to explain that he felt guilty, but in the end he glanced at the little pink elephant and left, this time for good.

I sat in my chair for a moment, wondering what would happen if I was unable to get those fifty pages typed before he left. Even if I had to work late I would find the necessary time, that wasn’t what worried me. But I can’t count on my eyes over a period of several hours. They get red and watery, I see stars, and sometimes they hurt so much I can’t see.

I was also thinking about Anita, stupid things: if I had known that morning that I was going to see her again, I would have worn my white suit; it was absolutely necessary that I stop at my apartment and change my clothes. Before, when I worked with her, I was still wearing skirts that I had made myself at the orphanage. She used to say, ‘You make me sick with your unhappy childhood and your home-made things.’ I wanted her to find me different, in my very best. Then suddenly I remembered that the boss had given me five minutes. With him five minutes meant exactly three hundred seconds. His punctuality would put a cuckoo clock to shame.

On a sheet of my pad I scrawled, ‘Gone for the weekend. Back Wednesday. Dany.’

But as soon as I had written that, I tore the page into little pieces and wrote on the next page, carefully this time, ‘Must catch a plane for the weekend. Back Wednesday. Dany.’

Now I felt like telling my life story. A plane was not enough. How about a plane for Monte Carlo? But I looked at my watch. The big hand was almost at half past five, and anyway I must be the only one in the agency who had never taken a plane, nobody would be impressed.

I clipped the note to the shade of my desk lamp. Anyone who came in could see it. I think I was happy. It is difficult to explain. It was as if I myself felt that impatience that I had sensed all afternoon long in the others.

As I put on my summer coat, I remembered that Anita and Michel Caravaille had a little girl. I took the pink elephant and put it in my pocket.

I remember that there was still sunlight on the window and on the papers piled on my desk.

In the car, a large black Citroën with leather seats, he himself suggested that we stop at my place first so I could pick up a nightgown and my toothbrush.

It was not the rush hour yet, so he drove rather quickly. I told him he seemed tired. He answered that the whole world was tired. Then I praised his car, but this did not interest him, and silence fell again.

We crossed the Seine at the Pont de l’Alma. He found a parking space on Rue de Grenelle in front of the camera shop across from my building. When I got out of the car, he followed me. He did not ask whether he could come up or anything. He walked into the building behind me.

I am not ashamed of my apartment – at least I don’t think I am – and I was sure I hadn’t left any underwear to dry over the gas radiator. Still, I was annoyed that he came up. He would take up all the room and I would have to change in a bathroom where when you tap one wall the other three echo the sound. Besides, it’s four flights up and there’s no lift.

I told him he did not have to come with me, that I would only be a few minutes. He answered that of course he would, that it was no trouble. I don’t know what he had in mind. Maybe that I was going to bring a suitcase.

There was nobody on my floor, which was all to the good. I have a neighbour whose husband treated himself to a holiday at the Boucicaut Hospital by getting smashed up on a one-way street. She carries on something awful if you don’t ask after him, and if you do she can go on all day. I preceded Caravaille to my apartment and closed the door as soon as he was inside. He looked around but said nothing. It was obvious that he did not know what to do with his big body. He seemed to me much younger and – how can I put it? – more real, more alive than at the office.

I took my white suit out of the wardrobe and shut myself in the bathroom. I heard him walking right next to me. As I undressed I told him through the door that there were drinks in the chest under the window. Did I have time to take a shower? He did not answer. I did not take a shower, I gave myself a quick sponge bath instead.