Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

A beautiful young woman lies sprawled on her berth in the sleeping car of the night train from Marseille to Paris. She is not in the embrace of sleep, or even in the arms of one of her many lovers. She is dead. The unpleasant task of finding her killer is handed to overworked, crime-weary police detective Pierre 'Grazzi' Grazziano, who would rather play hide-and-seek with his little son than cat and mouse with a diabolically cunning, savage murderer.Sébastien Japrisot takes the reader on an express ride of riveting suspense that races through a Parisian landscape of lust, deception and death. With corpses turning up everywhere, the question becomes not only who is the killer, but who will be the next victim . . .

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 313

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Sébastien Japrisot was a prominent French author, screenwriter and film director, and the French translator of J. D. Salinger. He is best known for A Very Long Engagement, which won the Prix Interallié in 1991 and was made into a film by Amélie director Jean-Pierre Jeunet. One Deadly Summer won the Prix des Deux Magots in 1978 and the film adaptation starring Isabelle Adjani won the César Award in 1984. Born in Marseille in 1931, Japrisot died in 2003.

Francis Price is a translator. His translations include God’s Bits of Wood by Ousmane Sembène.

Praise for The Sleeping Car Murders:

‘A strongly plotted story of murder with a clever ironical ending. For a first novel it is remarkable’

Daily Telegraph

‘Japrisot writes with warmth, and has a gift for rendering almost every character instantly likable’

New Yorker

‘Sébastien Japrisot’s talents as a storyteller have something of magic about them. You have to wait until the last page to be liberated from his grasp’

Quotidien de Paris

Praise for One Deadly Summer:

‘The most welcome talent since the early Simenons’

New York Times

‘A gripping tale of hatred, revenge, and lust … A sinister spellbinder’

Publishers Weekly

‘Japrisot’s talent lies in the clever construction of his novels that mimics a game of Meccano, each piece slotting neatly one into another. Of course, it also lies in the writing that is simple, rhythmical, surprising, phonetic and lyrical’

Le Point

‘Sébastien Japrisot holds a unique place in contemporary French fiction. With the quality and originality of his writing, he has hugely contributed to breaking down the barrier between crime fiction and literary fiction’

Le Monde

‘Unreeled with the taut, confident shaping of a grand master … Funny, awful, first-rate. In other hands, this sexual melodrama might have come across as both contrived and lurid; here, however, it’s a rich and resonant sonata in black, astutely suspended between mythic tragedy and the grubby pathos of nagging everyday life’

Kirkus Reviews

Praise for The Lady in the Car with Glasses and a Gun:

Voted one of the Sunday Times 100 Best Crime Novels

‘Utterly captivating, this is a perfect diversion for a sunny afternoon’

The Guardian

‘A riddle as captivating as it is terrifying’

Christian House

‘Full of suspense, absorbing, a fast mover … this is Japrisot’s finest suspense thriller’

L’Express

‘A cordon bleu mixture of suspense, sex, trick-psychology and fast action’

Publishers Weekly

‘Another success … Sébastien Japrisot has a very personal way of evoking fear’

Humanité Dimanche

Praise for A Very Long Engagement:

‘A classic of its kind, brewing up enormous pathos undiluted by sentimentality’

Daily Telegraph

‘The narrative is brilliantly complex and beguiling, and the climax devastating’

The Independent

‘Riveting … A fierce, elliptical novel that’s both a gripping philosophical thriller and a highly moving meditation on the emotional consequences of war’

New York Times

‘Diabolically clever … The reader is alternately impressed, beguiled, frightened, bewildered’

Anita Brookner, Man Booker-winning author of Hotel du Lac

A kind of latter-day War and Peace … A rich and most original panorama’

Los Angeles Book Review

‘Precisely, surprisingly evocative of the lingering pain of mourning and the burdens of survival’

Kirkus Reviews

Also available from Gallic Books:

One Deadly Summer The Lady in the Car with Glasses and a Gun

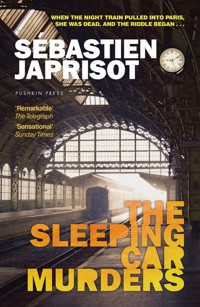

The Sleeping Car Murders

The Sleeping Car Murders

SÉBASTIEN JAPRISOT

Translated from the French by Francis Price

Adapted by Gallic Books

Pushkin Press

A Gallic Book

First published in France as Compartiment Tueurs

by Éditions Denoël, 1962

Copyright © Éditions Denoël, 1962

English translation copyright © Souvenir Press, 1964

First published in Great Britain in 1964 by Souvenir Press

This edition first published in 2020 by Gallic Books,

59 Ebury Street, London, SW1W 0NZ

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention

No reproduction without permission

All rights reserved

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologises for any errors or omissions and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781805334255

Typeset in Adobe Garamond by Gallic Books

Printed in the UK by CPI (CR0 4YY)

Contents

This Is the Way It Began

Berth 226

Berth 224

Berth 222

Berth 221

Berth 223

Berth 225

Berth 000

This Is the Way It Ended

This Is the Way It Began

The train was coming in from Marseille.

To the man whose job it was to go through the corridors and check the empty compartments, it was ‘the Phocéen – ten minutes to eight; after that, breakfast’. Before that, there had been ‘the Annecy – twenty-five minutes to’ on which he had found two raincoats, an umbrella, and a leak in the heating system. When he saw the Phocéen pull in on the other side of the same platform, he was standing by a window, looking at the broken nut on one of the valves.

It was a Saturday at the beginning of October, very clear and very cold. Travellers returning from the south, where people were still lying on the beaches and swimming, were surprised to see their breath form little clouds of vapour when they spoke.

The man who checked the corridors and compartments was forty-three years old. His name was Pierre, his political ideas were far to the left of centre, and he was thinking about a strike that was going to be called the following week. And things being what they are at 7:53 on a cold Saturday morning in Gare de Lyon, he was hungry, and looking forward to a good cup of coffee.

Since the trains would not be moved from their present location for at least half an hour, he decided, as he left the Annecy, to go and have his coffee before taking on the Phocéen. At 7:56 he was in an office that was being repaired, at the foot of track M. There was a steaming yellow cup with a red rim in his hand, his blue cap was pushed back on his head, and he was discussing the effectiveness of starting a strike on Tuesday with a short-sighted timekeeper and a North African labourer. Tuesday was a day when no one, absolutely no one, took the train.

He spoke slowly and deliberately, emphasising his view that a walkout was just like advertising: the important thing is to get your point across to the largest possible number of people. The others said of course, he was right. They almost always said he was right. He was a big man, heavy-set, with a deep voice and large, calm eyes that made him appear younger than he was. He had a reputation for being the kind of man who didn’t startle when someone came up behind him and clapped him on the back. He was a solid type.

At 8:05 he was going through the corridors of the Phocéen, opening the glass-panelled doors, glancing inside the compartments, closing the doors again.

In carriage No. 4, second-class, in the third compartment from the rear, he found a yellow and black scarf that had been left on one of the berths. He unfolded it, saw that it was printed with a drawing of the Bay of Nice, and recalled his own memories of Nice – the Promenade des Anglais, the casino, and a little café near Saint-Roch. He had been there twice: to a summer camp when he was twelve, and on his honeymoon, when he was twenty.

He had liked Nice.

In the next compartment, he found the corpse.

Although he was aways falling asleep in the cinema and missing parts of the film, he knew immediately that it was a corpse. The woman was stretched diagonally across the lowest of the three berths on the right, with her legs hanging awkwardly over the edge, so that her feet were hidden by the seat. Her eyes were open, stonily reflecting the light from the open door. Her clothing – a dark suit and a white blouse – was disordered, but no more so, he thought, than that of any traveller who had slept on a second-class berth fully dressed. Her left hand was clasped tightly around the edge of the berth. Her right hand was spread out flat on the thin mattress, so that her entire body seemed to have been petrified in the act of trying to get up. The skirt of the suit had been pulled up around the knees. A black court shoe with a very high heel was lying on the grey SNCF blanket, which was rolled in a ball at the foot of the berth.

The man who checked the corridors swore softly and stared at the corpse for twelve seconds. The thirteenth second, he looked at the lowered blind on the window of the compartment. The fourteenth, he glanced at his watch.

It was 8:20. He swore again, wondered vaguely which one of his superiors he should notify, and began searching in his pockets for a key to lock the compartment.

Fifty minutes later, the blind had been lifted and the sun had moved around so that its rays lay across the woman’s knees. Inside the compartment, the police photographer was aiming his camera at the recumbent figure, and flashbulbs were popping systematically.

The woman was dark-haired, young, rather tall, rather thin, and rather pretty. A little above the opening of her blouse there were two marks of strangulation on her neck. The lower one was a series of small round bruises, side by side. The upper, which was also deeper and more pronounced, was a straight line bordered with a blackish swelling. The doctor passed his index finger over it lightly, noting, and calling to the others’ attention the fact that it was not just a bruise on the skin: the black came off on his finger, as if the murderer had used something old or dirty.

The three men in overcoats behind him edged forwards to get a better look, and again there was a crunching sound from the pearls on the floor of the compartment. They were everywhere: lying in little patches of sunlight on the sheet around the woman, on the other lowest berth, on the floor, and even on the windowsill, two feet above the floor. One was found later in the right-hand pocket of the woman’s suit. They were fake pearls, from a costume-jewellery necklace of no value.

The doctor said that at first glance it appeared that the murderer had stood behind his victim, slipped a belt or something of the sort around her neck, and strangled her by pulling both it and the necklace, which had broken. There were no lacerations on the back of the neck, and the cervical vertebrae were not broken. On the other hand, the Adam’s apple and the lateral muscles had been badly crushed.

She hadn’t really defended herself. Her nails were carefully manicured, and the polish was chipped on only one – the middle finger of the right hand. The murderer, either intentionally or as a result of the struggle, had then thrown her back on the berth. He had completed the job of strangling her by tightening the ends of the belt on either side of the neck. Insofar as it was possible to judge, she had died within the space of two or three minutes. Death had taken place about two hours earlier, at approximately the time of arrival of the train.

One of the men in the compartment, seated on the edge of the bottom left-hand berth, with his hands in the pockets of his overcoat and his hat slightly askew on his head, asked a half-hearted question.

The doctor looked annoyed, but just to be sure, he lifted the woman’s head, leaning over so that he could study the back of the neck, and then said that of course it was a little early to give a definite answer, but that, in his opinion, the murderer need not have been either much bigger or much stronger than his victim. A woman could have done it as easily as a man. But women were not stranglers.

That was all he could do for the moment. He would examine the body at the Institute later in the morning. He picked up his case, wished the man who was seated on the other berth good luck, and left. He closed the door of the compartment behind him as he went out.

When the man who had spoken took his right hand out of his pocket, there was a cigarette clenched between two fingers. One of his companions gave him a light, then put his own hands back in his pockets and walked over to the window.

Just beneath him, on the platform, the men from the Criminal Records Office were standing about, smoking silently, waiting for the compartment to be turned over to them. A little further away a group of policemen, some curious station employees, and a couple of window cleaners were talking heatedly. A rolled-up canvas stretcher, with shiny wooden poles, was leaning against the railway carriage just beside the forward door.

The man looking out of the window took a handkerchief from his pocket, blew his nose, and announced that he was coming down with flu.

The man in the hat, still seated behind him, replied that that was too bad, but his flu would have to wait, because someone was going to have to take care of all this. He called the man at the window Grazzi, and said that it was he, Grazzi, who was going to take care of it. He got up, took off his hat, pulled a handkerchief from inside the band, blew his nose noisily, and said that, damn it, he had the flu too. Then he put the handkerchief back in the hat, and the hat back on his head, and said irritably that as Grazzi was going to handle it, Grazzi might just as well get started right away. Handbag. Clothing. Suitcase. First, who the woman was. Second, where she came from, where she lived, who she knew, and all that. Third, the list of reservations for the compartment. Report tonight at seven o’clock. A little less mucking about than usual wouldn’t do any harm – that bastard Frégard would be on this one. A word to the wise and all that … The trick would be to keep tight control of the investigation. Understood? Pull it all together.

He took his hands from his pockets and formed a circle with his arms, staring at Grazzi, who didn’t turn around. He just said, all right, he would have to see what’s-his-name about that slot-machine business, but he could manage.

The third man, who was gathering up the pearls from the floor, looked up and asked what should he do, boss? There was a barking sound, like laughter, and then the rasping voice said he might as well string the things he had in his hands. What else was he good for?

The man with the hat turned back to Grazzi who was still looking out of the window. Grazzi, very tall and thin in his navy-blue overcoat worn threadbare at the elbows, had dull brown hair and shoulders that carried the weight of thirty-five or forty years of dutiful submission. There was a cloud of smoke on the window in front of his face. He couldn’t have been able to see very much.

The man with the hat said not to forget, Grazzi, to look in the other compartments; you never know, and put everything you can think of into the report. Pull it together …

He was about to say something else, but instead he shrugged and just said, damn it, he’d caught a bad one. He looked down at the man with the pearls and said, I’ll see you at the office at noon, ciao. He went out without closing the door.

The man standing in front of the window turned around. His face was very pale, and his eyes blue and peaceful-looking. He said to the other man, who was leaning over the berth that held the stiff, dead body of the woman, that some people needed a good kick in the pants.

It was a little notebook with a spiral binding and a red cover spotted with grimy fingerprints. The man who was called Grazzi by his colleagues opened it in an office on the second floor of the station, to make notes on the first statements. It was almost eleven o’clock. Carriage No. 4 of the Phocéen had been moved to a siding, with the other carriages of the train. Three men, wearing gloves and carrying cellophane bags, were sifting its contents.

The Phocéen had left Marseille on Friday 4 October at 10:30 p.m. It had made its usual stops at Avignon, Valence, Lyon and Dijon.

The six berths in the compartment where the body had been found were numbered from 221 to 226, starting from the bottom, with the odd numbers to the left as you entered and the even numbers to the right. Five had been taken before the train left Marseille. Only one, 223, was empty, as far as Avignon.

The body had been lying on berth 222. The reservation stub found in the handbag indicated that she had boarded the train at Marseille, and that, unless she had changed places with someone, she had occupied berth 224 during the trip.

Tickets in the second-class carriages had been checked only once: after the stop at Avignon, between 11:30 and 12:30. The two employees who made this check had been reached by telephone. They stated that no one had missed the train, but to their great regret, they remembered nothing at all about the occupants of the compartment.

Quai des Orfèvres, 11:35 a.m.

The clothing, underclothes, handbag, suitcase, shoes and wedding ring were laid out on the table of one of the inspectors – although it was the wrong inspector. A typed carbon copy of the inventory made up by Bezard, a temporary clerk in the Criminal Records Office, was with them.

A tramp who was being questioned at a nearby table made a dirty joke about the paper bag, which had been torn in the course of its travels from one office to another and now revealed a cloud of white nylon. The man called Grazzi told him to shut up, and the tramp replied that unless they were going to listen to him, he wanted to leave. At this, the inspector seated across the table from him lifted a ham-like fist, and a woman who had witnessed a traffic accident ‘from beginning to end’ felt obliged to come to the help of the oppressed man. The resulting dispute was punctuated by the clatter of objects dropped by Grazzi in an attempt to move everything to his own table in one trip.

Before the incident was finally settled, Grazzi knew most of what there was to be learned from the assorted items. As he worked over the inventory, portions of them spread from his table to his chair and then to the floor, and onto other tables, and the other inspectors on duty began cursing under their breath about this idiot who couldn’t stay within the space provided for him.

The typed inventory from the Criminal Records Office was accompanied by several explanatory notes: a pearl found in the right-hand pocket of the dark suit had been sent to be examined with the others collected on the train; the fingerprints taken from the handbag, the suitcase, the shoes, and the objects inside the handbag and the suitcase were almost all those of the victim herself, and it would require some time to compare what others there were with those taken in the compartment, since they were neither clear nor recent; a button missing from the blouse had been found in the compartment and would be examined along with the pearls; a carefully folded piece of paper found in the handbag, bearing some clumsy, obscene drawings with the caption ‘A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush’, was undoubtedly some sort of travelling salesman’s vulgar riddle. And, as a matter of fact, the riddle was incorrect: from the care Bezard had taken (fourteen typed lines) to explain why it would not work, it was easy to see that the boys upstairs had had a good time. The riddle would be the house problem for today.

*

By noon the riddle had, in fact, made its way through several floors of the building. The boss, sitting at his desk with his hat pushed back on his head, trying to forget his cold, had a copy of it in front of him and was proposing solutions to three laughing subordinates who had their own ideas about it.

There was a sudden silence in the room when the one they called Grazzi came in, his shoulders bowed, blowing his nose.

The boss pushed his hat back even further and said, all right, boys, he had to talk to Sherlock Holmes and from the look on his face he wasn’t getting anywhere – you can run along. There was still a trace of laughter in the corners of his mouth and eyes. He picked up a pencil, placed the point on a sheet of paper covered with the drawings from the riddle, and began to fill them in carefully, while Grazzi, leaning against a radiator, deciphered the notes in his little red book in a mournful voice.

The victim’s name was Georgette Thomas. Thirty years old. Born at Fleurac, in the Dordogne. Married when she was twenty, to Jacques Lange. Divorced four years later. Height 5 feet, 4 inches, dark hair, blue eyes, fair complexion, no distinguishing marks or scars. Demonstrator-saleswoman for a cosmetics firm, Barlin. Lived at No. 14, Rue Duperré. Went to Marseille on a demonstrating job for the company from Tuesday 1 October to Friday night, 4 October. Stayed at the Hôtel des Messageries, Rue Félix Pyat. Ate her meals in different restaurants on Rue Félix Pyat or in the business district. Earned 922 new francs a month, less social security. Bank account at the moment: 774 new francs and 50 centimes. Cash in her handbag, 324 new francs, 93 centimes, and one Canadian dollar. Robbery did not seem to be the motive for the murder. An address book still had to be checked out. Nothing particularly strange in her personal effects: an empty aspirin tube she might have meant to throw away; several photographs, all of the same child; a letter addressed ‘My pigeon’, about a postponed rendezvous and vaguely affectionate, but undated and unsigned. That was all.

The boss said good, it was as simple as good morning, they had to get people to start talking. He extracted a crumpled cigarette from a pocket, straightened it out between his fingers, and began searching for a match. Grazzi struck one and held it out to him. Leaning towards the flame, the boss said first, Rue Duperré, if that’s really where she lived. He puffed on the cigarette, coughed, and said he ought to stop smoking. Second, the people in this Barlin outfit. Third, find her relatives and send someone to identify her.

He studied the drawings on the paper in front of him and said, with a faraway smile, that it was very funny. What did Grazzi think?

Grazzi hadn’t thought about it.

The boss said okay and got up. He had to meet his son for lunch in a bistro in Les Halles. His son wanted to go to the Beaux-Arts and study God knows what. Twenty years old and nothing in his head. The trumpet and the Beaux-Arts – those were the only things he was interested in. His son was an idiot.

As he was putting on his coat, he paused, stuck out an index finger, and said Grazzi could believe him, his son was an idiot. Unfortunately, that didn’t change your feelings. Grazzi could really believe him, this son of his was breaking his heart.

He said, okay, they would see each other later in the afternoon. And not to forget the list of reservations. The railways were never in a hurry. But there was no need to swamp the lab with a raft of examinations. Strangling some woman, that wasn’t the work of a pro. Before Grazzi knew it, some poor sucker would fall into his lap, admitting guilt and going on about how he loved her, and all that. All Grazzi would have to do is pull it all together for that bastard, Frégard.

He buttoned his overcoat over a red-checked woollen scarf and a stomach that made him look pregnant. He studied the knot on Grazzi’s tie carefully. He never looked anyone straight in the face. Some people said there was something wrong with his eyes, something that had happened when he was a child. But who was going to believe he had ever been a child?

In the corridor he turned back to Grazzi, who was just going into the inspectors’ room, and said he had forgotten something. This business of the slot machines: he shouldn’t worry about that at the moment, there were too many people involved. So there was no point in getting tangled up in it; let the boys upstairs worry about it. If there were any newspapers sniffing around, fob them off with this murdered woman – they’d like her – and shut up about the rest. A word to the wise, etc….

The first newshound who came sniffing around caught Grazzi by the sleeve at four o’clock that afternoon, when he came back from a visit to rue Duperré with the blond boy who had gathered up the pearls. He had the serious smile and the prosperous look of the ones who work for France-Soir.

Grazzi offered him the female corpse in Gare de Lyon with all the usual caveats and then produced a bonus from his wallet: a copy of a photo of the victim. Georgette Thomas looked almost as she had when her body was found, carefully made-up and with her hair in perfect order, easily recognisable.

The reporter whistled, took some notes, consulted his watch, and said that he would run over to the Medico-Legal Institute right away: he had a ‘buddy’ there who would let him in and with any luck he could catch the concierge from Rue Duperré, who had gone to identify the victim. He still had fifty minutes to get the story in for the last editions.

He left so fast that all of the other newshounds picked up the scent, and within the next half-hour every newspaper in Paris knew about the story. But by then it had no interest for them; it was too late for the last editions, and the next day was Sunday.

*

At 4:15, unbuttoning his overcoat and preparing to get on the telephone and see where the victim’s address book would lead, Grazzi saw on his table a handwritten list of the reservations for berths 221 to 226 on the Phocéen. The six travellers had reserved their places anywhere from twenty-four to forty-eight hours in advance.

One good turn deserves another. Grazzi telephoned the Medico-Legal Institute to ask the reporter to include the list in his story. At the other end of the line someone asked him to hold on a minute, and Grazzi said he would.

Berth 226

René Cabourg had been wearing the same old-fashioned, belted overcoat for eight years. A good part of the year he also wore knitted wool gloves, a long-sleeved sweater, and a heavy scarf that bulged awkwardly around his neck. He was subject to recurring attacks of the flu, and as soon as the weather turned cold, his naturally sullen disposition became even more nervous and irritable.

He left the Paris-South district branch of the Progine Company (‘Progress-in-your-kitchen-through-engineering’) every night a few minutes after 5:30. There was a bus stop on Place d’Alésia just in front of the office, but he always walked to the terminus for the No. 38 at Porte d’Orléans, to be sure of getting a seat. All the way from Porte d’Orléans to Gare de l’Est he never lifted his eyes from his newspaper. He always read Le Monde.

This particular night – which was not a night like all the others in any event, because he had returned just that morning from the only trip he had taken in ten years – several unusual things occurred. In the first place, he left his gloves in a drawer of his desk, and since he was anxious to get home as quickly as possible – his room had not been cleaned since before he went away – now that he was outside he decided not to go back and get them. After that, he stopped in a brasserie at Porte d’Orléans and drank a glass of beer, which was something he never did on ordinary days. He had been thirsty ever since leaving Marseille; the compartment on the train had been overheated, and he had slept with his clothes on, because there were women and he had not been sure his pyjamas were clean. The next thing that happened that night was that he went to three newsstands after coming out of the brasserie without finding a copy of Le Monde. The last edition hadn’t come in yet. He gave up in the end, and bought a copy of France-Soir.

Seated on the No. 38 at last, in the middle, away from the wheels and next to a window, he turned the front page without looking at it. The inside pages were more sedate, and didn’t irritate him quite so much. He had never liked shouting or loud laughter or vulgar stories, and large, black headlines had the same effect on him.

He was tired, and conscious of the pressure between his eyes, which always preceded an attack of the flu. He had slept badly on the train; he had been afraid of falling out of the upper berth, and used his sweater as a pillow because he didn’t trust those provided by the SNCF. The heat had been unbearable, and even when he had dozed off he could hear the clacking of the wheels and the intermittent burst of sound from the loudspeakers in the stations. And in addition to that, he had worried about all sorts of stupid things: an accident, an exploding steam pipe, the theft of the wallet beneath his head; God knows, all sorts of stupid things.

He had left Gare de Lyon without his scarf and with his overcoat hanging open. During the whole week he was in Marseille, it had been almost like summer. He could still see the dazzling sunlight on the Canebière one afternoon at about three o’clock, when he had walked the whole length of it down to the Old Port. There had been all the bright colours of the girls’ dresses, and the rustling sounds of their skirts as they walked, and that always disturbed him a little. Now he had the flu, all right; there was no doubt about that.

He didn’t know why it should be that way, but it always was. Probably because of the girls, because of his timidity, and his thirty-eight solitary years. Because of the envying glances he was ashamed of but could not always repress when he passed a young couple, laughing and happy. Because of the idiotic pain it caused him just to see them.

He thought of Marseille, which had been a torture worse than any springtime in Paris, and of a night in Marseille just forty-eight hours ago. The thought made him lift his eyes and look around him, like a fool. Even as a child, he had had that same reaction, wanting to be sure that no one suspected what he was thinking. Thirty-eight years old.

Two seats ahead of him on the bus, a young girl was reading Le Monde. He looked out the window, saw that they were already at Châtelet, and he had not really read a single line of his paper.

He would go to bed early. He would have dinner, as he always did, at Chez Charles, the restaurant on the ground floor of the building he lived in. He would put off the cleaning until tomorrow; he had all of Sunday morning for that.

He was still not reading the paper, but just staring at it mechanically, his eyes wandering from one paragraph to the next, and when he saw his own name he scarcely noticed it. It was not until two lines further on, when he saw a sentence that said something about night, berths, and a train, that he stopped.

He read the sentence then, but it told him only that something had happened the night before, in a compartment on the Phocéen. When he went back to the line where he had seen his name, he learned that someone named Cabourg had occupied a berth in this compartment.

He had to open the paper wide and go back to the front page to find the beginning of the article. The man sitting next to him muttered something or other, irritably.

It was the photograph above the headline that really startled him. In spite of the fuzzy quality of the newspaper picture, it had the slightly shocking reality of a face you think you have seen for the last time, thank God, and then find again on the next street corner.

Beyond the grey and black of the ink, he could see the colour of her eyes, the thickness of her hair, and the warmth of the smile that had brought on everything at the very beginning of the trip last night – the unreasoning hope he had felt for a while, and then the shame and disgrace at a quarter past twelve. A whiff of a perfume he had vaguely disliked came back to him, recalling the moment when the woman raised her voice, although she had been standing right next to him. When she turned around, the movement of her shoulders had been sharp and swift, like that of a boxer who has seen an opening, and her eyes were like that, too: one of the sharp-eyed little boxers in the preliminaries at the Central on Saturday nights.

There seemed to be a hard knot forming in his throat, beating to the rhythm of his pulse. He could feel it so clearly that he raised his left hand and touched his thumb and index finger to his neck. As he turned towards the window, instinctively looking for his own reflection, he realised that they were going down Boulevard de Strasbourg; they were almost at Gare de l’Est.

He read the caption beneath the photograph and a few lines of the beginning of the article, and then folded the paper. There were still a dozen or so people on the bus. He got off last, clutching the rumpled newspaper in his right hand.

As he walked across the busy square in front of the station, he recognised the sounds and smells that were a part of it and should be familiar to him, since he passed here every night, but which he had never really noticed before. A train whistled somewhere in the depths of the brightly lit building, and there was a noise of engines starting up.

They had found the woman strangled on one of the berths, after the train arrived in the station. Her name was Georgette Thomas. For him, last night, she had been only a gilt ‘G’ on a handbag, someone who spoke in a deep, almost husky voice and had offered him a cigarette – a Winston – when they exchanged a few words in the corridor. He didn’t smoke.

On the pavement on the other side of the square he couldn’t stand it any longer, and stopped and unfolded the newspaper again. He was nowhere near a street light, and he couldn’t see to read. Still holding the paper open in his hand, he pushed through the glass doors of a brasserie. The place was so hot and noisy that for an instant he considered turning back, but then he blinked and went in. He found an empty place on a bench at the back, next to a couple who were talking in carefully guarded tones.

He sat down without taking off his overcoat, pushed away two empty glasses on cardboard coasters, and spread the paper across the shiny red surface of the table.

The man and woman were watching him. They must have been about forty years old, the man perhaps a little more, and they had the worn, slightly sad expressions of two people who meet for an hour or so after work every day, even though their lives are centred somewhere else. René Cabourg thought they were ugly, even a little repulsive, because they were no longer young, because the woman’s chin and neck were beginning to sag, because a husband or a band of children was probably waiting for her at home, because of everything.