Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Vertigo

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

A young woman wakes in a hospital room. What happened to her and why is a mystery. Is she victim or murderer?The young woman has been badly injured in a fire and has amnesia. But what happened to her? Is she Mi, Micky or Michèle, or Do, Dominique? As she struggles to rebuild her identity, she starts to recall the crime that was committed and the house on the French Riviera. She remembers the rich heiress and the faithful friend - but which is she?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 239

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Sébastien Japrisot was a prominent French author, screenwriter and film director, and the French translator of J. D. Salinger. He is best known for A Very Long Engagement, which won the Prix Interallié and was made into a film by Amélie director Jean-Pierre Jeunet (2004). One Deadly Summer won the Prix des Deux Magots in 1978 and the film adaptation starring Isabelle Adjani won the César Award in 1984. Born in Marseille in 1931, he died in 2003.

Helen Weaver is an American writer and translator. She has translated more than fifty books from French. Antonin Artaud: Selected Writings was a Finalist for the National Book Award in translation in 1977.

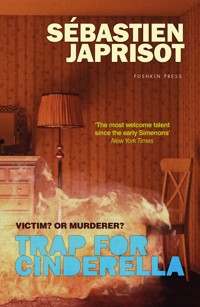

Praise for Trap for Cinderella

‘A psychological thriller … beautifully ingenious’

Oxford Mail

Praise for The Sleeping Car Murders

‘Japrisot writes with warmth, and has a gift for rendering almost every character instantly likable’

New Yorker

Praise for One Deadly Summer

‘The most welcome talent since the early Simenons’

New York Times

Praise for The Lady in the Car with Glasses and a Gun

‘Utterly captivating, this is a perfect diversion for a sunny afternoon’

The Guardian

Praise for A Very Long Engagement

‘A classic of its kind, brewing up enormous pathos undiluted by sentimentality’

Daily Telegraph

Trap for Cinderella

Also available from Gallic Books

One Deadly SummerThe Lady in the Car with Glasses and a GunThe Sleeping Car Murders

Trap for Cinderella

SÉBASTIEN JAPRISOT

Translated from the French by Helen Weaver

Adapted by Gallic Books

Pushkin Vertigo

A Gallic Book

First published in France as Piège pour Cendrillonby Éditions Denoël, 1962

Copyright © Éditions Denoël, 1962

English translation copyright © Souvenir Press, 1965

First published in Great Britain in 1965 by Souvenir Press

This edition first published in 2021 by Gallic Books, 59 Ebury Street, London, SW1W 0NZ

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention

No reproduction without permission

All rights reserved

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologises for any errors or omissions and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781805335979

Typeset in Adobe Garamond by Gallic Books

Printed in the UK by CPI (CR0 4YY)

CONTENTS

I WOULD HAVE MURDERED

I MURDERED

I WOULD HAVE MURDERED

I SHALL MURDER

I MURDERED

I MURDER

I HAD MURDERED

I WOULD HAVE MURDERED

Once upon a time, long ago, there were three little girls; the first was Mi, the second was Do, and the third La. They had a godmother who smelled nice, who never scolded them when they were bad, and whom they called Aunt Midola.

One day, they were in the garden. Godmother kisses Mi but does not kiss Do and she does not kiss La.

One day, they are playing weddings. Godmother chooses Mi, she never chooses Do and she never chooses La.

One day, they are sad. Godmother, who is going away, cries with Mi, says nothing to Do and nothing to La.

Of the three little girls, Mi is the prettiest and Do is the most intelligent. La will soon be dead.

La’s funeral is a big event in the lives of Mi and Do. There are many candles and many hats on a table. La’s coffin is painted white, the cemetery earth is soft. The man digging the hole wears a jacket with gold buttons. Godmother Midola has returned. To Mi, who gives her a kiss, she says, ‘My love,’ to Do, ‘You’re making my dress dirty.’

The years pass. Godmother Midola, who is always referred to in hushed tones, lives far away and writes letters with spelling mistakes in them. One day she is poor and makes shoes for rich ladies. One day she has lots of money and buys beautiful houses. One day, because Grandfather has died, she arrives in a big car. She makes Mi try on her beautiful hat, she looks at Do without recognising her. The cemetery earth is soft, and the man throwing it into the hole wears a jacket with gold buttons.

Later Do becomes Dominique and Mi becomes Michèle who lives far away and whom they sometimes see at holiday time. Mi makes her cousin Do try on beautiful organdie dresses. She delights the whole world as soon as she opens her mouth, receives letters from the godmother that begin ‘My Love’ and cries over her mother’s grave. The cemetery earth is soft and Godmother keeps her arm around the shoulders of Mi, of Micky, of Michèle, and murmurs things Do cannot hear.

Later it is Mi who is in black because now she has no mother, and who says to Do, ‘I need, I need, I need to be loved.’ It’s Mi who always wants to take Do’s hand when they go for walks.

It’s Mi who says to her cousin Do, ‘If you kiss me, if you hold me close, I won’t tell anyone, I’ll marry you.’

Later still, perhaps two years later, perhaps three, it’s Mi who kisses her father on an airport runway, in front of the big bird that will take her far away to Godmother Midola in a honeymoon country, to a city that Do searches for with her finger on a map.

And still later, it’s Mi who is only ever seen in photographs in glossy magazines. One day, she has long black hair. She enters an immense gilded marble hall in a ballgown. One day, she has long legs, she reclines in a white swimsuit on the bridge of a white sailing boat. One day, she drives a little open-topped car full of young people, waving, with their arms around each other. Sometimes, her pretty face is serious, a slight frown above her beautiful blue eyes, but that’s because of the sun reflected off the snow. Sometimes she smiles, close to the camera, staring straight into the lens, and the caption, in Italian, says that one day she will be one of the richest women in the country.

And even later, Aunt Midola will die, as fairies die, in her palazzo in Florence or Rome or on the Adriatic, and it will be Do who invents this tale, which she well knows, since she is no longer a little girl, is false.

It is just true enough to stop her sleeping. But Aunt Midola is not a fairy, she’s a rich old lady who still makes spelling mistakes, whom she has only ever seen at funerals, who is no more her godmother than Mi is her cousin: those are just the things you say to the children of cleaning ladies, like Do, and like La, because it’s kind and harms no one.

Do, who is twenty, like the little princess with the long hair in the magazine pictures, every year receives slippers made in Florence. That’s probably why she calls herself Cinderella.

I MURDERED

Suddenly there is a great burst of white light, blinding me. Someone leans over me, a voice stabs my head, I hear screams echoing in distant corridors, but I know they are mine. I breathe in blackness through my mouth, a blackness peopled with strange faces, with murmurs, and I die again, happy.

A moment later – a day, a week, a year – the light returns on the other side of my eyelids, my hands burn, and my mouth, and my eyes. I am rolled down empty corridors, I scream again, and it is black.

Sometimes the pain is concentrated in a single spot behind my head. Sometimes I am aware of being moved, of being rolled elsewhere, and the pain spreads through my veins like a tongue of flame drying up my blood. In the blackness there is often fire, there is often water, but I no longer suffer. The sheets of flame frighten me. The columns of water are cold and sweet to my sleep. I want the faces to fade away, the murmurs to die down. When I breathe in blackness through my mouth, I want the blackest black, I want to sink as deep as possible into the icy water, and never to come up.

Suddenly I come up, dragged towards the pain by my whole body, nailed by my eyes under the white light. I struggle, I howl, I hear my screams from a great distance, the voice that stabs my head brutally says things I do not understand.

Black. Faces. Murmurs. I feel good. My child, if you start that again, I’ll slap your face, with Papa’s fingers which are stained from cigarettes. Light Papa’s cigarette, angel, the fire, blow out the match, the fire.

White. Pain on the hands, on the mouth, in the eyes. Don’t move. Don’t move, child. There, easy. This won’t hurt. Oxygen. Easy. There, good girl, good girl.

Black. A woman’s face. Two times two is four, three times two is six, ruler blows on the fingers. We walk in a line. Open your mouth wide when you sing. All the faces walk in two lines. Where is the nurse? I don’t want any whispering in class. We will go to the beach when the weather is fine. Is she talking? At first she was delirious. Since the graft she complains of her hands, but not her face. The sea. If you go far out too, you will drown. She complains of her mother, and of a schoolteacher who used to hit her on the fingers. The waves went over my head. Water, my hair in the water, go under, come up again, light.

I came to the surface one morning in September, with lukewarm hands and face, lying on my back on clean sheets. There was a window near my bed, and a great splash of sunlight in front of me.

A man came and spoke to me in a very gentle voice, for a time which seemed to me too short. He told me to be a good girl, and try not to move my head or hands. He cut off his syllables when he spoke. He was calm and reassuring. He had a long bony face and large black eyes. But his white gown hurt my eyes. He realised this when he saw me lower my eyelids.

The second time he came in a grey woollen jacket. He spoke to me again. He asked me to close my eyes for yes. I had pain, yes. In my head, yes. On my hands, yes. On my face, yes. I understood what he was saying, yes. He asked me whether I knew what had happened. He saw that I kept my eyes open, in despair.

He went away and my nurse came to give me an injection so I could sleep. She was tall, with large white hands. I realised that my face was not uncovered like hers. I made an attempt to feel the bandages, the salve, on my skin. Mentally I followed, piece by piece, the strip that wound around my neck, continued over the nape of my neck and the top of my head, wound around my forehead, missed my eyes, and wound once more around the lower part of my face, winding, winding. I fell asleep.

In the days that followed, I was someone who is moved around, fed, rolled through corridors, who answers by closing her eyes once for yes, twice for no, who tries not to scream, who howls when her dressings are changed, who tries to convey with her eyes the questions that oppress her, who can neither speak nor move, a creature whose body is cleansed with ointments, as her mind is with injections, a thing without hands or face: no one.

‘Your bandages will be removed in two weeks,’ said the doctor with the bony face. ‘Although I have mixed feelings about that: I rather liked you as a mummy.’

He had told me his name: Doulin. He was pleased that I was able to remember it five minutes later, and even more pleased to hear me pronounce it correctly. Before, when he used to hover over me, he would simply say mademoiselle, or child, or good girl, and I would repeat mamaschool, goodiplication, mamarule, words which my mind knew were wrong, but which my stiffened lips formed against my will. Later he called this ‘telescoping’; he said that it was the least of our worries and would disappear very quickly.

Actually it took me less than ten days to recognise verbs and adjectives when I heard them. Common nouns took me a few days more. I never recognised proper nouns. I was able to repeat them just as correctly as the others, but they meant nothing to me besides what Dr Doulin had told me. Except for a few like Paris, France, China, Place Masséna, or Napoleon, they remained locked in a past which was unknown to me. I relearned them, but that was all. It was pointless, however, to explain to me what was meant by to eat, to walk, bus, skull, clinic, or anything that was not a definite person, place, or event. Dr Doulin said this was normal, and I was not to worry about it.

‘Do you remember my name?’

‘I remember everything you’ve said. When can I see myself?’

He moved away, and when I tried to follow him with my eyes it hurt. He returned with a mirror. I looked at myself, me: two eyes and a mouth in a long, hard helmet swathed in gauze and white bandages.

‘It takes over an hour to undo all that. What’s underneath should be very pretty.’

He was holding the mirror in front of me. I was leaning back against a pillow, almost sitting up, my arms at my sides, tied to the bed.

‘Are they going to untie my hands?’

‘Soon. You’ll have to be good and not move around too much. They’ll be fastened only at night.’

‘I see my eyes. They’re blue.’

‘Yes, they’re blue. You’re going to be good now: not move, not think, just sleep. I’ll be back this afternoon.’

The mirror vanished, and that thing with blue eyes and a mouth. The long bony face reappeared.

‘Sleep tight, little mummy.’

I felt myself being lowered into a lying position. I wished I could see the doctor’s hands. Faces, hands, eyes were all that mattered just then. But he was gone, and I went to sleep without an injection, tired all over, repeating a name which was as unfamiliar as the rest: my own.

‘Michèle Isola. They call me Mi, or Micky. I am twenty years old. I’ll be twenty-one in November. I was born in Nice. My father still lives there.’

‘Easy, mummy. You’re swallowing half your words and wearing yourself out.’

‘I remember everything you’ve said. I lived for several years in Italy with my aunt who died in June. I was burned in a fire about three months ago.’

‘What else did I tell you?’

‘I had a car. Make, MG. Registration number, TTX 664313. Colour, white.’

‘Very good, mummy.’

I tried to reach out to keep him from going, and a stab of pain shot up my arm to the nape of my neck. He never stayed more than a few minutes. Then they gave me something to drink, they put me to sleep.

‘My car was white. Make, MG. Registration number, TTX 664313.’

‘The house?’

‘It’s on a promontory called Cap Cadet, between La Ciotat and Bandol. It had two storeys, three rooms and a kitchen downstairs, three rooms and two bathrooms upstairs.’

‘Not so fast. Your room?’

‘It overlooked the sea and a town called Les Lecques. The walls were painted blue and white. This is ridiculous: I remember everything you say.’

‘It’s important, mummy.’

‘What’s important is that I’m repeating. It doesn’t mean anything. They’re just words.’

‘Could you repeat them in Italian?’

‘No. I remember camera, casa, macchina, bianca. I’ve already told you that.’

‘That’s enough for today. When you’re better, I’ll show you some photographs. I have three big boxes of them. I know you better than you know yourself, mummy.’

It was a doctor named Chaveres who had operated on me, three days after the fire, in a hospital in Nice. Dr Doulin said that this operation, after two haemorrhages on the same day, had been wonderful to watch and full of amazing details, but that he wouldn’t want any surgeon to have to repeat it.

I was in a clinic on the outskirts of Paris run by a Dr Dinne. I had been moved there a month after the first operation. I had had a third haemorrhage on the plane when the pilot had been forced to gain altitude a quarter of an hour before landing.

‘Dr Dinne took charge of you as soon as the graft had passed the critical stage. He made you a pretty nose. I’ve seen the plaster cast. It’s very pretty, I assure you.’

‘What about you?’

‘I am Dr Chaveres’s brother-in-law. I work at Saint Anne’s. I’ve been looking after you from the day you were brought to Paris.’

‘What have they done to me?’

‘Here? They’ve made you a pretty nose, mummy.’

‘But before that?’

‘That doesn’t matter now; what matters is you’re here. You’re lucky to be twenty years old.’

‘Why can’t I see anyone? If I saw someone, my father, or anyone I knew, I’m sure everything would come back to me in one blow.’

‘You have a way with words, my dear. You’ve already had one blow on the head which gave us enough trouble. The fewer you have now, the better.’

Smiling, he moved his hand slowly towards my shoulder and let it rest there for a moment without pressure.

‘Don’t worry, mummy. Everything is going to be fine. In a while your memory will come back a little at a time, without a fuss. There are many kinds of amnesia, almost as many as there are amnesiacs. But you have a very nice kind: retrograde, lacunar, no aphasia, not even a stammer, and so comprehensive, so complete, that now the gap can only get smaller. So it’s a tiny, tiny little thing.’

He held out his thumb and index finger, almost touching, for me to see. He smiled and rose with deliberate slowness, so that I would not have to move my eyes too abruptly.

‘Be good, mummy.’

*

The time came when I was so good that they no longer knocked me out three times a day with a pill in my broth. This was in late September, nearly three months after the accident. I could pretend to be asleep and let my memory beat its wings against the bars of its cage.

There were sun-filled streets, palm trees by the sea, a school, a classroom, a teacher with her hair pulled back, a red wool bathing suit, nights illuminated by Chinese lanterns, military bands, being offered chocolate by an American soldier – and the gap.

Afterwards, there was a sudden burst of white light, the nurse’s hands, Dr Doulin’s face.

Sometimes I saw again very clearly, with a harsh and disturbing clarity, a pair of thick butcher’s hands with large but nimble fingers and the face of a stout man with cropped hair. These were the hands and face of Dr Chaveres, glimpsed between two blackouts, two comas, a memory which I placed in the month of July, when he had brought me into that white, indifferent, incomprehensible world.

I did mental calculations, the back of my neck painful against the pillow, my eyes closed. I saw these calculations being written on a blackboard. I was twenty. According to Dr Doulin, the American soldiers were giving chocolate to little girls in 1944 or ’45. My memories did not go beyond five or six years after my birth: fifteen years wiped out.

I concentrated on proper names, because these were the words that evoked nothing, were connected with nothing in this new life I was being forced to live. Georges Isola, my father; Firenze, Roma, Napoli; Les Lecques, Cap Cadet. It was useless, and later I learned from Dr Doulin that I was banging my head against a brick wall.

‘I told you not to fret, mummy. If your father’s name means nothing to you, it is because you’ve forgotten your father along with everything else. His name doesn’t matter.’

‘But when I say the word river, or fox, I know what it means. Have I seen a river or a fox since the accident?’

‘Look, when you’re yourself again, I promise you we’ll have a long talk about it. Meanwhile I would rather you remained quiet. Just tell yourself you’re going through a process which is definite, understood, one might almost say normal. Every morning I see ten old men who haven’t been hit on the head and who are in almost exactly the same state. Five or six years back is just about the limit of their memories. They remember their schoolteacher, but not their children or grandchildren. This doesn’t prevent them from playing their belote. They have forgotten almost everything, but not belote or how to roll their cigarettes. That’s the way it is. You’ve got us stymied with an amnesia of a senile variety. If you were a hundred, I’d tell you to take care of yourself and that would be that. But you’re twenty. There’s not one chance in a million that you will stay like this. Do you understand?’

‘When can I see my father?’

‘Soon. In a few days they’ll take off this medieval contraption you have on your face. After that, we’ll see.’

‘I want to know what happened.’

‘Another time, mummy. There are things I want to be very sure of, and if I stay too long, you’ll get tired. Now, what’s the number of the MG?’

‘664313 TTX.’

‘Are you purposely saying it backwards?’

‘Yes I am! I can’t stand it! I want to move my hands! I want to see my father! I want to get out of here! You make me say the same stupid things over and over every day! I can’t stand it!’

‘Easy, mummy.’

‘Stop calling me that!’

‘Calm yourself, please.’

I lifted one arm, an enormous plaster fist. This was the afternoon of ‘the fit’. The nurse came. They retied my hands. Dr Doulin stood against the wall opposite me and stared at me with eyes full of shame and resentment.

I howled, no longer knowing whether it was him or myself I hated. I was given an injection. I saw other nurses and doctors come into the room. I believe it was the first time that I actually thought about my physical appearance. I had the sensation of seeing myself through the eyes of those who were watching me, as if I were two people in this white room, this white bed. A formless thing, with three holes, ugly, shameful, howling. I howled with horror.

Dr Dinne came to see me in the days that followed, and talked to me as if I were a five-year-old girl, a little spoilt, something of a nuisance, who had to be protected from herself.

‘If you start that performance again, I won’t be responsible for what we’ll find under your bandages. You’ll have only yourself to blame.’

Dr Doulin did not come back for a whole week. It was I who had to ask, several times, for him. My nurse, who must have been criticised after ‘the fit’, answered my questions reluctantly. She untied my arms for two hours a day, during which time she kept her eyes fastened on me, suspicious and ill at ease.

‘Are you the one who stays with me while I sleep?’

‘No.’

‘Who’s that?’

‘Someone else.’

‘I’d like to see my father.’

‘You’re not ready to.’

‘I’d like to see Dr Doulin.’

‘Dr Dinne does not wish it.’

‘Tell me something.’

‘What?’

‘Anything. Talk to me.’

‘It’s not allowed.’

I looked at her large hands, which I found beautiful and reassuring. Eventually she became aware of my gaze and was annoyed by it.

‘Stop watching me that way.’

‘You’re the one that’s watching me.’

‘You need to be watched,’ she said.

‘How old are you?’

‘Forty-six.’

‘How long have I been here?’

‘Seven weeks.’

‘Have you taken care of me all that time?’

‘Yes. That’s enough, now.’

‘How was I at first?’

‘You didn’t move.’

‘Was I delirious?’

‘Sometimes.’

‘What did I say?’

‘Nothing of interest.’

‘What, though?’

‘I can’t remember now.’

At the end of another week, another eternity, Dr Doulin came into the room with a package under his arm. He was wearing a dirty raincoat which he did not remove. The rain beat against the window panes beside my bed.

He came over to me, touched my shoulder the way he always did, very quickly and gently, and said, ‘Hello, mummy.’

‘I’ve waited a long time for you.’

‘I know,’ he said. ‘I got a present out of it.’

He explained that someone outside the clinic had sent him flowers after ‘the fit’. The bouquet – dahlias, because his wife liked them – was accompanied by a little key ring for the car. He showed it to me. It was a round object, in gold, which struck the hours. Very useful for parking in a restricted parking zone.

‘Was it my father who sent the present?’

‘No. Someone who has taken care of you since the death of your aunt, whom you have seen much more of than you have of your father in the last few years. It’s a woman. Her name is Jeanne Murneau. She followed you to Paris. She asks after you three times a day.’

I told him that this name meant nothing to me. He took a chair, set the timer on his key ring, and put it on the bed near my arm.

‘In fifteen minutes it’ll ring and I’ll have to go. How do you feel, mummy?’

‘I wish you’d stop calling me that.’

‘After tomorrow I’ll never call you that again. You’ll be taken to the operating theatre in the morning. Your bandages will be removed. Dr Dinne thinks everything should be nicely healed.’

He unwrapped the package he had brought. It was photographs, photographs of me. He handed them to me one at a time, watching my eyes. He did not seem to expect me to recognise anything. At any rate, I did not. I saw a girl with black hair who looked very pretty, who smiled a great deal, who had a slender figure and long legs, who was sixteen in some of the pictures and eighteen in others.

The pictures were glossy, beautiful, and horrible to contemplate. I did not even try to remember this clear-eyed face, nor the series of landscapes I was shown. From the first photograph, I knew it would be wasted effort. I was happy, eager to look at myself and unhappier than I had been since I had opened my eyes under the white light. I felt like laughing and crying at once. In the end, I cried.

‘There, there. Don’t be silly.’

He put the pictures away, in spite of my desire to see them again.

‘Tomorrow I’ll show you some others in which you are not alone, but with Jeanne Murneau, your aunt, your father, friends you had three months ago. You mustn’t expect this to bring back your past. But it will help you.’

I said yes, that I had confidence in him. The key ring rang near my arm.

I walked back from the operating theatre with the help of my nurse and an assistant of Dr Dinne’s: thirty steps along a corridor of which I saw only the tiled floor under the towel that covered my head. A black and white chequerboard pattern. I was put back in bed, my arms more tired than my legs, because my hands were still in their heavy casts.

They arranged me in a sitting position with the pillow behind my back. Dr Dinne, in a suit, joined us in the room. He seemed pleased. He watched me curiously, attentive to my every movement. My naked face felt cold as ice.

‘May I see myself?’

He motioned to the nurse. He was a stout little man without much hair. The nurse came towards the bed with the mirror in which I had seen myself in my mask two weeks before.

My face, my eyes looking at my eyes: a short, straight nose. Skin taut over prominent cheekbones. Full lips opening in an anxious little smile, slightly plaintive. A colour not ghastly, as I was expecting, but rosy, freshly scrubbed. In short, a very attractive face, which lacked naturalness because I still did not dare move the muscles beneath the skin, and which I found decidedly oriental because of the cheekbones and the eyes, which were drawn towards the temples. My face, immobile and mysterious, down which I saw two warm tears trickle, then two more, and two more. My own face, which was becoming blurred, which I could no longer see.

‘Your hair will grow back fast,’ said the nurse. ‘Look how much it’s grown in three months under the bandages. Your eyelashes will get longer too.’

Her name was Madame Raymonde. She did the best she could with my hair: there was three inches of it to hide the scars, and she arranged it a lock at a time to give it body. She washed my face and neck with cotton wool. She smoothed my eyebrows. She seemed to have forgiven me for ‘the fit’. She prepared me every day as if for a wedding.

She said, ‘You look like a little monk, or Joan of Arc. Do you know who Joan of Arc was?’