Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

'A gripping account of the cloak and dagger game played in Berlin and beyond by Britain's shadow warriors. A knife-edge Cold War showdown. A game of secrets, masterfully told.' – Damien Lewis, Sunday Times No. 1 Bestselling Author The British Commanders'-in-Chief Mission to the Soviet Forces in Germany, better known as BRIXMIS, was arguably the most successful and enduring intelligence organisation of the whole Cold War. Its three-man teams maintained a permanent presence behind the Iron Curtain, patrolling East German soil every single day from 1946 until the fall of the Berlin Wall changed the face of post-war Europe. In a follow-up to The Deadly Game, Will Britten, a career Military Intelligence Officer, treats us to a fresh, and in places hard-hitting look at his experience as one of the last generations of Cold War warriors. Over the Wall details reconnaissance missions in the depths of the DDR, targeting by Stasi surveillance teams, and fascinating personal contacts with 'the enemy'. Beyond this, he puts forward the shocking proposition that Moscow had almost certainly compromised BRIXMIS through their own agents operating within the wide US military system. Providing a rare insight into the activities of the GRU-staffed Soviet military teams deployed reciprocally in West Germany, Over the Wall ultimately poses an intriguing question: in the final balance whose missions were operationally more effective?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 568

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Map of the former DDR.

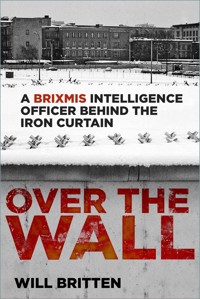

Jacket illustrations: Front: The Berlin Wall at Potsdamer Platz in 1979. (2ebill/Alamy Stock Photo) Back: The author with a trio of fraternal comrades. (Author photo)

First published 2025

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Will Britten, 2025

The right of Will Britten to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 857 2

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

To those who watched and to those we watched.

To Roy P, who inspired me to join the unit, and toMark Lucas for sowing this literary seed.

And to my children.

(May 2021)

The names of all Allied military personnel have been changed to protect their privacy and, in some cases, their personal security, unless they are already in the public domain. Some of these characters appear in The Deadly Game. I have used the names of Soviet officers as they were given to us.

‘In the fields of observation chance favours only those minds which are prepared.’

Louis Pasteur – presciently capturing the essence of Military Mission ‘touring’.

Contents

Preface

1 Questions (and Answers)

2 The Alpha: The Beginning

3 The Mission

4 Training – Ours Not Theirs

5 The Road to Berlin

6 BRIXMIS

7 Flashback

8 On Pass

9 Touring

10 My Touring

11 The Beginning of the End

12 A Brief History of Time

13 The New Normal

14 Russian Friends

15 Real Research

16 A Blot on the Landscape

17 Rebirth

18 A Last Glance Back Over My Shoulder

19 The Omega: The End

Annex A: Debrief of a Stasi Officer

Annex B: The Robertson-Malinin Agreement

Annex C: Glossary

Annex D: Glossary of Equipment

Index

Preface

The crack and thump of three high-velocity shots hammered against the warm, taut air of the early spring afternoon.

It was 24 March, a Sunday, two years after the fear and tension that scarred 1983, and four and a half years before the disbelief and ecstasy of the 9 November revolution – still the far-off dream that no one yet had had the courage to conjure with – when the Berlin Wall came tumbling down.

The Soviet command, sitting in Zossen Wünsdorf, just 50km south of Berlin, had imposed a temporary restricted area (TRA) to cover a large-scale exercise that the Allied Military Missions’ operations staffs assessed could involve the assets of up to three separate German Democratic Republic-based Red Army divisions. A two-man tour had crossed the Glienicke Bridge in the early hours of the morning from the light and freedom of West Berlin into the pervading greyness of Potsdam, timed to hit the southern fringes of the exercise area as the TRA was scheduled to lift. Their tasking was to move northwards, to rummage through pre-selected areas and specific locations in the hopes of finding documentary or other intelligence left behind by the units as they withdrew from the exercise area and returned to barracks.

A quick check of this sector of the training area by the tour crew had discovered signs of activity but nothing of intelligence value worth recovering back to West Berlin. The tour officer in command paused a moment, once back in the safety and security of his military green Mercedes G-Wagen, to decide on the team’s next move before heading north to remain in sync with the tour plan, the intent to visit Neubukow, near the port of Rostock, by dark before completing their 1,500km sweep and returning back to base late the following evening. He had just three or four more tours at most before his posting in the Mission was over and he moved on to his next assignment – he was keen to maximise the intelligence he brought home before his posting. One more push and maybe one more success.

He decided they would call in quickly at Ludwigslust, 190km into the heartland of the Deutsche Demokratische Republik (DDR), from where the team had crossed over from West Berlin into the east. Ludwigslust was home to a Motor Rifle Regiment subordinated to 21 Motor Rifle Division, a formation that had often in the past been one of the first units in the Group of Soviet Forces in Germany (GSFG) to receive new equipment entering front-line service in the DDR. It was to be one of the last decisions he made as a Mission tourer and the most fateful of his life.

Just sitting on the edge of a permanently restricted area (PRA) were two small training areas. One of them had a small shed capable of temporarily housing up to eight tanks or self-propelled tracked artillery guns. On a Sunday it was possible that it could be full, awaiting a resumption of normal training the following morning. Even hard-pressed Red Army conscripts had one day of rest per week.

The team approached cautiously, as the previous summer a French tour had been shot at whilst surreptitiously checking a tarpaulin-covered vehicle parked outside the same shed. Confirming the immediate area was clear, the tour officer lowered his binoculars and instructed the driver/tour NCO, a staff sergeant, to pull forward slowly, circling the shed to ensure it was clear of sentries on the other, blind, side and to park up so he could slip out and stealthily check the padlocked main door. Neither soldier had spotted the Soviet guard resting out of sight in the shaded treeline, enjoying the spring warmth. But, critically, he had spotted and recognised them and understood their role and mission.

The time was 1.30 p.m. The G-Wagen halted and the officer cautiously alighted from the front passenger seat and pushed shut his door. The driver swung open the turret hatch above him and raised himself up and out to increase his visibility as he watched his commander cover the 40m to the shed door.

He felt the first shot pass close over his head like an angry hornet. Instantly, instinctively, he dropped back onto his seat, explosively pulling closed and securing the hatch, now above his head, in one fluid movement. Two further shots rang out and there, lying on the ground, face down, was Major Arthur ‘Nick’ Nicholson, the United States Military Liaison Mission (USMLM) senior ground touring intelligence officer. He raised his head.

‘Jesse, I’ve been shot,’ were his last words as he slumped back into the pool of his own blood spreading steadily over the dampened earth.

Staff Sergeant Jesse Schatz, one of the most experienced drivers and tour NCOs in the American Mission, was firmly ordered, at gunpoint, by the Soviet soldiers and young officer, who were soon on-scene taking control of the incident, to remain in the vehicle, despite him holding up the tour’s first aid box with its universal red cross stencilled on the lid.

Major Nicholson died of his wounds a short time later, essentially bleeding to death for lack of an effective medical response, as Schatz looked on helplessly, powerless to do more than offer a silent prayer.

This incident could have happened to any Allied tour operating in this northern zone of Mission activity. In the spirit of ‘all for one and one for all’, the fact it was an American musketeer who tragically lost his life, and not one from either the French Military Liaison Mission or the British Mission (BRIXMIS) was mere chance, a coincidental dance to the music of time. Nick Nicholson had been conducting himself professionally; neither he nor his tour vehicle were in an area where they should not have been, and both his and the tour NCO’s conduct posed no direct threat, or the implication of threat, to any member of the nearby Soviet garrison. It was a classic case of wrong place, wrong time, compounded by wrong sentry, wrongly or, more appropriately, poorly trained and briefed. It is even feasible that Russian wasn’t even the sentry’s first language

But what the incident, ultimately, graphically demonstrated was the inherent danger of conducting reconnaissance missions ‘over the Wall’, behind the front line, deep inside enemy territory, and the existential risks the Allied Mission tours had faced every single day over the four decades during which they conducted this vital, and unique, intelligence collection operation against the Warsaw Pact, the length and breadth of communist East Germany, throughout Cold War history.

1

Questions (and Answers)

To make some sense of the tragic tale of Major Nicholson’s death, and to colour the landscape and create some context, perspective and relief, there are some key assumptions – acknowledgement of the gist of each – which underpin the detail of the ‘what, where, when and how’ of the historical events leading to that fateful afternoon.

If I pressed you that on every day for forty-four years, from late 1946 to the end of 1990, on-duty members of the British Army, the Royal Air Force and occasional members of the Royal Navy had been engaged on officially sanctioned military operations, travelling throughout East Germany – the DDR – demonstrably behind the Iron Curtain, would you believe me?

If I confirmed to you that these British servicemen were also joined by members of the US and French armed forces, would you believe this too?

If I was to persuade you that they travelled overtly in the uniforms of their respective services, in plainly marked civilian vehicles, with, in the British case, Union flags unequivocally visible, does that sound credible?

What about if I continued to tell you their primary raison d’être was to systematically conduct acts of espionage – crudely put, to ‘spy’ – on the Red Army and their comrades-in-arms in the DDR’s Nationale Volksarmee, clandestinely seeking to report on the operational doctrine and capability of the five massive enemy Soviet ground armies – as they occupied over 750 barracks spread over 270 separate locations, exercising on nearly 120 training areas – and 11 divisions of the NVA based in East Germany? Further, that they routinely conducted intelligence collection missions against these Warsaw Pact barracks, the seemingly never-ending cycle of training exercises, the four dozen airfields from which the Soviet Air Force flew, and all the road and rail movement of equipment, seeking to remain updated on their organisation, tactics and equipment … feasible and credible?

If I put it to you that these teams were regularly under hostile surveillance mounted by the East German Ministry of State Security (MfS) – Stasi – frequently shot at by Soviet sentries and guards, and others were assaulted and beaten, and that not only Major Nicholson but another member of the Allied Missions lost their life to enemy action, could you believe that to be true?

And finally, if I stated that teams comprising these soldiers, sailors and airmen were on hand to monitor the Soviet force’s reaction to every escalation of tension during the Cold War and to inform their own governments’ decision-making process, when, with every turn of the screw, the prospect of war seemingly loomed larger, from the Berlin Airlift to the Cuban Missile Crisis, the invasions of Hungary and Czechoslovakia, the building of the Berlin Wall, the tensions of the Reagan years and, finally, the collapse of the Wall and the overthrow of Gorbachev, would you believe this?

Incredibly, each and every one of these tantalising scenarios is true. They relate to, and shape the story of, the Allied Military Missions – unique and remarkable military intelligence units that ranged across East Germany throughout the duration of the Cold War.

This is essentially, but not exclusively, the story of the British servicemen who belonged to the British Commanders’-in-Chief Mission to the Soviet Forces in Germany (BRIXMIS for short), and their contribution over these four decades that undoubtedly contributed to the maintenance of a wider, but by no means ubiquitous, European peace that has endured from the end of the Second World War right up to today. It is also a personal perspective from my own brief sojourn, arguably bridging the most dramatic days, as the unit transitioned from the seemingly unrelenting pack ice of the Cold War to the bright spring of Wende – the drama of the Berlin Wall trembling and then collapsing into rubble – to the bright, bright sun of summer as the Soviet bear dramatically about-turned and began its trudge eastwards, rather than westwards, back towards the uncertainty of its own end of empire.

This book is not the first to be written about BRIXMIS – or ‘the Mission’ as it was more colloquially referred to – and there are other books published in English detailing life in the US Mission. What I aim to accomplish, against the wider backdrop, is the telling of some of my personal experiences as a professional intelligence officer serving in the Mission right at the very end of its life. Then, for the first time, give a flavour of the operations carried out by the Joint Intelligence Staff (Berlin), the son of BRIXMIS, once German reunification had precipitated the Mission’s demise and most of its personnel had packed up and been posted home, until, in August 1994, the last Russian soldier, atop the last Russian tank, had left East Germany. I conclude with a brief taster, the coin flipped over, of what our Soviet opposite numbers, in their Missions based in West Germany, may have been up to – seemingly a very different but, to date, poorly documented story.

As a ‘memoir’ it is as honest and complete as I can make it. I have withheld some tales and experiences that should best remain untold, held back on some detail in others with an eye on security and in response to redactions requested during the process of security review by the Ministry of Defence but, frankly, these instances are few and debatable; I am talking about events that occurred more than thirty years ago, after all.

Operationally, BRIXMIS was not a hi-tech, high-value strategic intelligence unit, nor was it subordinated to any national agency. The equipment and tactics we used were basic and essentially extensions of the arsenal and fieldcraft of the infantry soldier. Put crudely and over-simply, but I think nonetheless succinctly, the espionage activities of the Mission revolved around a group of blokes, albeit highly trained and motivated, driving around a country the size of Cuba or Iceland or the state of Tennessee, searching for, then looking and watching and recording the military activity of our sworn Cold War enemies.

But, my colleagues and the generations who went before us did it very, very well.

If the sense emerges that there is a dearth of detail on the nitty-gritty of ‘touring’, I would agree. Again, frankly, there is only so much one can say about rattling around in the back of a jeep, with sometimes very little happening beyond the windshield, without it very quickly becoming repetitive and tedious – and it has been said elsewhere, achieving exactly the right blend and balance. What follows are the ‘best bits’ that remain fresh and vibrant in my memory – and thankfully I have always been blessed with a pretty good one. If I have recorded errors or made mistakes in recounting details, they are innocent and devoid of any intent. I am confident they don’t alter the price of fish.

Finally, these pages also seek to give some impression and overview of how the Mission evolved from its first tentative baby steps in bombed-out, war-torn occupied eastern Germany to the unique, professional intelligence unit it became, and to elaborate on some of its key successes during those amazing forty-four years of operational activity. In so doing, I am aware that some of my own personal observations and conclusions may antagonise former Mission members. Comments about the ultimate contributions will not please everyone. But I sincerely believe I am only fleetingly reflecting what the recent release of new material and its publication suggests, and do not seek in any way to belittle, disparage or, worse, indulge in the ghastly modern, at best passive-aggressive and at worst wokist, trend to rewrite history – the amazing history of BRIXMIS, its twin siblings, and those worthy Cold War warriors who served within.

2

The Alpha: The Beginning

If you are younger than 40, I wager you have few personal memories of the decades we know as the Cold War. But was there ever a period in history when two enemies faced off against each other against such a backdrop shaped by mutual suspicion, distorted misunderstanding and tangible fear? Was there ever a period in history when mankind confronted the reality of mutually assured destruction and the end of the modern age – conceivably the end of history itself? There was: it was during these years.

If you are beyond the tender age of two score years, unless you are the very last of those Japanese soldiers still hiding out in a South East Asian jungle, you will have little difficulty recalling the trademarks, chapters and dialect of the Cold War. What about sputnik, Apollo, MiG, B-52, U-2, Polaris, SS-21, Cruise, Kalashnikov, KGB, GRU, CIA, Stasi, Checkpoint Charlie, KoreanWar, the space race, the arms race, the bomber gap, the missile gap, the re-scramble for post-independence Africa, the Caribbean missile stand-off, Vietnam, the invasions of the Soviet satellites, and the saga of Berlin – the airlift, the ‘doughnut’ speech, the Wall and its dispiriting tales of divided families and failed escapes? Some of the restrained language masking the potential death of hundreds of thousands will sound familiar: air bridge; Brezhnev Doctrine; DEFCON, ‘defense readiness condition’; first strike capability; intercontinental ballistic missile; anti-ballistic missile; Star Wars; military-industrial complex; atom, hydrogen, and neutron bomb; nuclear deterrence; nuclear fallout; rollback; and the most chilling throwaway three words of the whole Cold War, in fact the scariest but most apt acronym in any language: MAD – mutually assured destruction.

But even if you recognise one key iconic symbol of the whole surreal story, the ideological division of Berlin, do you still remember how the carving up of post-war Germany looked? When I talk to my kids about the old West Germany, the former DDR and the sectors of Berlin, their return gaze is blank, and frankly their interest begins to quickly flag. When I explain not just the reality of a divided Berlin and the 43km of its Wall, its geometry of guard towers anchoring each and every 250m section of its length, the minefields and the vehicle traps, but the significance of this division, a capitalist western half, reflecting light, glitz, consumerism and personal freedom onto the drab, grey prison of socialism on the other side of their Wall, they struggle to grasp it. My words convey as much meaning and relevance as if I was miming in a blacked-out room.

Continue to elucidate on the wire that further divided ‘mainland’ Germany to the west of Berlin from the North Sea to the Czech border, and one might as well be speculating on the prospect of life on a Venusian moon. It is now ancient history set against the constraints and boundaries of our contemporary collective goldfish-like attention span and our unrestrained worship of self, and yet it was very real, the epitome of Dr Strangelove craziness: illogical, cynical and ultimately pointless driven waste. It did not, and still does not, make sense.

3

The Mission

This reality was, however, the genesis from which life was breathed into one of the most effective and longest-enduring intelligence units in modern military history: BRIXMIS – the British Commanders’-in-Chief Mission to the Soviet Forces in Germany, later rebranded, in response to a Soviet name-changing initiative, to British Commanders’-in-Chief Mission to the Western Group of Forces.

The Mission, as it was universally referred to by the relatively limited circle who were aware of the scope and scale of its roles, was an enduring product of both the alliance that defeated Nazi Germany and the ideological divergence that followed and defined the Cold War until its end.

By 1946, indeed earlier if you search carefully for the nascent cracks and fissures that permeated the anti-Nazi entente, it was clear to all that the wartime band of brothers was fracturing as distrust, fear and a wider and established, deeper-rooted geopolitical mould reasserted and reimposed itself to shape the new European, and global, reality.

Triggered by the precedent of the London Agreement of November 1944, an early prescient commentary on the perception of the growing problems attending this rebirth was the Robertson-Malinin Agreement, signed by the British and Russian military representatives who gave the document their names. It created a framework to guarantee the ease of continuing dialogue and liaison between the British military commander and the Red Army commander sitting in their respective post-conflict German headquarters in their respective military zones of influence within shattered, liberated Germany. It crafted a mechanism and means to ‘jaw, jaw’, to misquote but anticipate the words of Churchill – a prototypical confidence-building measure. The wording of the three agreements – an American and French version followed hard on the heels of the British–Soviet original – ultimately ensured the longevity of the Allied Military Missions they created. The Missions were enabled to adopt new tactics and approaches, fundamentally to evolve into the intelligence units that they all became – if the agreements’ wording neither permitted nor prohibited, that development was generally deemed acceptable.

In the key spirit of reciprocity that underpins diplomacy, the small bilateral military liaison staffs that the agreements gave birth to were guaranteed free and unobstructed movement within their respective zones to deliver messages on each and every day of every ensuing year, with no limit on the duration of this pragmatic, realistic and remarkably far-sighted requirement.

Interestingly, the original 1946 charter indirectly imposed a number of additional, broader tasks pertinent at the time for the first two or three years of BRIXMIS’s activity. During this time the Mission was subordinated to the Control Commission Germany, and the team’s members were actually paid directly by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, sitting back in King Charles Street in Whitehall, until 1950 when ‘ownership’ was transferred to what would eventually become the Ministry of Defence. Consequently, personnel were charged with supporting the repatriation of prisoners of war, displaced persons and deserters, and as part of the Commission’s de-Nazification programme, they played a part in tracing and extraditing war criminals. More widely, they were active registering war graves and helped adjudicate the settling of minor border disputes. And, perhaps surprisingly, Mission personnel were also mandated to feature in anti-black-market operations. These must have been challenging but professionally exciting and fulfilling times.

Accordingly, the British quasi-diplomatic staff was established, in preference to Karlshorst amidst the rubble of East Berlin, in Potsdam, in Soviet military territory in the south-western leafy suburbs of Berlin. Potsdam was selected as the location for the British Mission’s official headquarters – although, in practical terms, Mission members lived in, and the de facto headquarters was situated in, the security of West Berlin – so it could be co-located with the Rear HQ of GSFG before it was moved to the former German Wehrmacht HQ and Army high command in Zossen Wünsdorf. A Russian team, known for ever afterwards as SOXMIS, the Soviet Military Mission, was staffed and eventually housed in Bünde, within striking distance of the British military headquarters, in the heart of the British zone. The Soviets chose not to mirror the Allies’ approach of operating from a safe base within their own territory. This is to say that the three Soviet Missions, operating in West Germany within each of the Allied zones of occupation, did not cross and re-cross the Inner German Border (IGB) from base locations within the DDR at the commencement and end of each tour. In the case of SOXMIS, they chose to be fully contained within their compound in Bunde, in contrast to the way the Allied Military Liaison Missions (AMLMs) crossed the Glienicke Bridge from West Berlin touring onwards from the Mission Houses in Potsdam. I suspect this approach was forced upon them, based on a pragmatic logistical assessment and the realities of time and distance.

Key to the agreement, and an enduring feature, was the maintenance of a system of ‘passes’, limiting the size of each team and effectively restricting the numbers who could transit through each respective military zone at any one time.1 Critically, the passes guaranteed free, unobstructed passage to those Mission members who carried them. The British team received thirty-one passes for eleven officers and twenty additional supporting staff.

Identical reciprocal agreements, but with a smaller allocation of passes, between the Soviets and the US (the Huebner-Malinin Agreement establishing USMLM) and the French (Noiret-Malinin Agreement, FMLM) followed hard on the Soviet–British precedent the following year. In contrast, the US negotiated a mere fourteen passes, perhaps with, I suspect, a keener focus on the reciprocal number of Soviet officers this would allow to enjoy free movement in their zone, and the French eighteen. They too both formally established their Missions in Potsdam, with a back foot in their respective zones in West Berlin. This created a framework whereby British, American and French soldiers had near free access to what became, in 1948, the DDR, and Soviet military personnel roamed the respective zones of their former allies in the Bonn Republic, also known as the Federal Republic of Germany.

Complete freedom of movement was subsequently qualified in October 1951 by the imposition, in all four occupation zones, of PRAs, which guaranteed a degree of protection to areas – approximately 20 per cent of each of the zones – that the hosts wished to remain off limits to casual terrestrial ‘enemy’ observation. These ‘goose eggs’ enclosed hundreds of square kilometres of choice military real estate – a combination of sensitive base locations and training areas. Those in the DDR were individually hand drawn onto small-scale maps and passed on to the Allied Missions by SERB (the Soviet External Relations Bureau), which provided, essentially, an administrative interface. By their very nature, these maps were a totally inaccurate tool and certainly not fit for purpose in adjudicating subsequent disputes as to whether a tour was in or out of a restricted area. It was, however, clearly understood that where PRAs landed on Autobahns (the world’s first motorways), they could be transited by tours and, indeed, it was acceptable for a tour vehicle to halt on the roadside and for the crew to undertake observation tasks.

Fixing an upper limit on the percentage of territory that could be protected, this could, however, be augmented by limited-duration TRAs. TRAs were a convenient way of greatly increasing the size of areas out of bounds to tours by using them to link individual areas of PRAs when the integrity of a large deployment or training exercise had to be maintained.

A third form of restriction, which tours did not take seriously, has to be noted simply because there were so many of them: mission restriction signs. They had first come into existence also, in 1951 as local initiatives by Soviet commanders to limit Allied Mission access to their establishments and local areas, with absolutely no derived authority from the three original Mission agreements. The practice spread to cover the whole of GSFG, and indeed NVA installations. It is estimated that in 1964 there were well over 1,200 of them country-wide, almost as numerous as Hoxha’s Dalek-like reinforced concrete pill boxes sown the length and breadth of Albania. By 1989 the number must have been even greater, but by then no one had the time or inclination to log them. Whilst they generated absolutely no protection to units sitting ‘inside signs’, they were fairly reliable indicators to a tour that had spotted them that they were approaching a barracks, some other form of installation or training area. New signs likely indicated a new target or, perhaps more likely, the fact they had been erected to replace old signs ‘stolen’ by tours as mementos and farewell reminders of life on tour. I regret not having ‘half-inched’ one, but it was another symptom of the ‘oh, I’ll get one next time’ attitude like tomorrow, there is rarely the right next time – it never comes.

As tensions mounted and Cold War ice solidified into its state of seeming glacial permanence, the liaison role of the Military Missions, East and West, rapidly morphed into a new primary function that progressively grew and increased in relevance, becoming more and more focussed. Their liaison roles continued to play a vital role in de-escalating and managing tension at various key points during the freeze, but they evolved irreversibly into a wider function. The Missions became full-time dedicated intelligence-gathering units.

The Allied Missions’ first intelligence task was to construct an Order of Battle for the Red Army units that were deployed in eastern Germany. This required teams to identify each and every unit at every formation level and trace their subordination in a meticulous and painstaking manner, filling the blank, virgin canvas. This intelligence was then briefed to the various intelligence staffs the other side of the Iron Curtain in western Germany, London, Paris, Washington DC and later in Brussels when NATO HQ relocated there from outside of Paris.

Tasking from Moscow to the three Soviet Missions, plus Berlin-centric city flag tours mounted through Checkpoint Charlie, I suspect, bore a few subtle variations, as I will later discuss, that cascaded down to our own Allied teams. This would have resulted, it was always consistently assessed, in at least a much more focussed agent-support function due to a more aggressive Soviet view of human intelligence (HUMINT) collection and SOXMIS staff’s relatively easier and safer freedom of movement in western Germany vis-à-vis Soviet intelligence officers operating with diplomatic cover, or indeed as illegals.2

Although Russian xenophobia and paranoia, pre-dating 1917 and extending back into Czarist days, would have required their military teams to monitor, with greater or lesser intensity, Allied states of armed readiness, the western Missions performed this role with an enhanced existential and timorous focus. BRIXMIS, from the day of its first tour on 5 October 1946, and the other two Allied Missions, for the entirety of its operational life, played a vital role in NATO’s early warning system. Its presence – 365 days per year over the Wall, behind enemy lines, on the ‘wrong’ side of the Iron Curtain – was an integral and bespoke strand of the tripwire designed and resourced to warn the generals, and their political masters, of the Soviets’ advance westwards towards the Channel ports, thereby, in design, giving them just enough time to execute their relentlessly rehearsed defensive plans to degrade and halt it.

If the wire was tripped, and successfully reacted to – a big ‘if’ of history that thankfully remained untested – the warning would likely, at least in part, have been triggered by the reconnaissance work of BRIXMIS and tours from the other Allied Missions. These tours were, certainly latterly, carefully coordinated by the Missions’ operations staffs. The aim was to ensure there was a permanent presence monitoring the key units of the five Soviet ground armies and an air army – some twenty-four divisions – of GSFG, plus the additional eleven divisions of the NVA. The 300,000-plus Soviet conscripted troops of GSFG relentlessly trained within, and rotated through, this mammoth military machine. So, the doctrine dictated, if the Red Army was gearing up for that fateful and final advance, the Mission tours would not miss the intensification of activity associated with mobilisation. They might, indeed, be the sole Allied source reporting this fearful, fateful development. The stark reality was that such movement might not necessarily be detected by the strategic collection assets that traded in Signals intelligence (SIGINT) and Imagery intelligence (IMINT) – scrupulous radio discipline and bad weather could frustrate the Allied signals intelligence units listening in to GSFG radio and cypher traffic, and blind overhead collection by satellites or fixed-wing overflights.

The Missions were the unblinking eyes of the free West through every crisis that punctuated post-war history, from the sealing of Berlin – it was a BRIXMIS tour officer who reported the laying down of the first rough blocks of the Wall – to the ingress in 1968 of Red Army units over the Czech border from the deep south of East Germany, to the invasion of Afghanistan, right up to that potentially destabilising November evening, and the weeks and months following, when the Wall so dramatically came tumbling down.

A fundamental complementary function of this role, observing Soviet military preparedness, was the unrivalled opportunity to gather a whole cross-section of military and infrastructure-related intelligence. This involved monitoring the unending cycle of training exercises from the initial low-level training, marking the arrival of the latest influx of raw conscripts every six months, to the culmination of their two-year tours of duty in the divisional and Army-level combined large set-piece exercises. It encompassed commenting on levels of competence of both ground and air forces, assessing tactical doctrine, identifying and evaluating new equipment in the Soviet arsenal and recovering a mountain of technical intelligence that few other collection platforms and agencies had the opportunity or potential to gather. In infrastructure terms, teams were able to bring west de visu intelligence reporting on everything from the DDR’s rail network and uranium ore mining to the span of key bridges and the state of repair and implied capability of other key pieces of infrastructure to the identification of auxiliary runways routinely engineered into the Autobahn network. So simple, so direct, so reliable, so unbelievably cost effective, but potentially strategically priceless to the Western alliance.

Significantly, by way of a footnote, the post-war Mission model lived on beyond its own demise in 1989. It served to influence the various arms control negotiations, and shape the resultant teams that were configured to monitor the specific and knotty detail of their agreements, playing their full part in keeping the world a safer place.

_______

1 I have included a copy of my pass in the photo section.

2 There are few, if any, detailed and informed open-source treatises, that I am aware of, on the work of the Soviet Missions, but there are enough ‘whispers’ to begin to paint a much more nuanced output. Really weighty source material would necessarily have to come from within archives inside Russia. A fascinating project in waiting for an author or PhD student if these sources survived the collapse of the Soviet Union.

4

Training – Ours Not Theirs

My arrival in the Mission was yet another fortuitous twist of fate, benevolent karma, that had characterised the eight years of my career since leaving university. In fact, I should include those three years of study in this calculation as, from my first year at university, a martial god had smiled on me, pushing, prodding, leading, then preparing me to secure my Cadetship. This had meant all my university fees had been paid by the Army, plus a salary as a second lieutenant had flowed monthly into my bank account – I have never been wealthier. And certainly my father was delighted: no requirement to bankroll this son. As I looked back at the almost casual, certainly unorthodox, way I had slipped into the Special Duties world, on the back of that first posting to 123 Intelligence Section in Lisburn in Northern Ireland, then my three tours of duty in the Force Research Unit running covert agents against the terrorist groupings in Northern Ireland, my charmed destiny-driven luck had continued with equal, almost unbelievable, good fortune.3

In my early meetings with Ray, before I formally handed over South Detachment, Force Research Unit (FRU) to him, he had talked about his days ‘in the Mission’ in Berlin touring around eastern Germany watching the Russians. It was hard to believe this was an operation that we, the British Army, were engaged in and had been for so long. As Ray talked more, I was struck by what a well-kept and enticing secret the real role of this extraordinary unit appeared to be. He spoke about shooting incidents, rammings, and other rough-house stuff, racing at high speed to avoid pursuit by the Stasi or Russian military vehicles and regular contact, not just with ordinary Russian officers and soldiers but with uniformed members of the KGB and GRU, Soviet military intelligence. Tales of the day-in and day-out operation to collect intelligence against these sorts of challenges represented exactly my idea of a good posting and the next job I needed after the high-octane life of a FRU Detachment commander. I had heard the name BRIXMIS during my attachment to 3 Intelligence and Security Company, stationed in Berlin, during my final long summer break once I had sat my university finals, but I had had no clear understanding of the unit’s role. All I had really known was that it was a very sensitive unit and was considered to be another tool in the ‘Special Duties box’ that contained other units like the FRU and 14 Coy across the water. Ray made it sound very, very interesting indeed to the low-boredom threshold and restlessness of my character.

I had been looking at the prospect of either remaining in Northern Ireland in an intelligence liaison role with the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) Special Branch or returning to Specialist Intelligence Wing to run the training that supplied the FRU with its operators, back in Ashford. In the event, I had fallen out of sync with these openings when I decided to take the opportunity to return to the FRU for one final year as the unit’s intelligence officer, a new position basically controlling the flow of intelligence within the headquarters and its dissemination out of the unit to our strategic-level partners – essentially, but not exclusively, to the upper levels of the Special Branch. Against this reality, when the Intelligence Corps’ officer manning desk mentioned the prospect of a posting to Berlin and Ray’s old unit, I bit off their hand so quickly and cleanly there was not a single drop of blood to spoil the worn carpet.

I have reflected so many times on the perversity of fate – my choice, following Ray’s advice, leading me to yet more adventure against unorthodox and irregular backdrops; Ray’s decision to serve with the FRU ultimately leading him to his tragic and untimely death in the Chinook crash on the rugged Galloway coast of Scotland six years later in 1994, along with twenty-eight other military, police and civilian intelligence officers.

As I pulled up and parked below London Block, the imposing, utilitarian Nazi-era sports administration building within the ‘Olympic Stadium’ complex that was the Mission’s West Berlin home – so named, without irony or, indeed, imagination, because the 1936 stadium was just a javelin’s throw across the playing fields – I had absolutely no comprehension of what the next three years would bring. I was certainly thrilled and excited to be back on the island that was Berlin, looking up to the stone eagles that had kept a watchful eye on BRIXMIS all these years. How tumultuous these coming years would be with the re-alignment in European, and ultimately world, history, and how the role of the Mission would change in so few months from my applying the handbrake on my BMW, were well beyond the limits of my imagination and, I am positive, the occult powers of others.

I had joined the Special Duties course run by Attaché Branch based in Templer Barracks in Ashford, Kent, the home of the British Army’s specialist cadre of professional intelligence officers, the Intelligence Corps, earlier that summer. The year was 1989, seemingly unremarkable but how portentous a date.

Attaché Branch schooled our military attachés on fulfilling whatever intelligence tasking they would be mandated to fulfil in-post. Clearly this was little in the case of those going to Washington DC, Ottawa or Canberra, but a little more onerous in the case of Moscow or Beijing, or the capitals of strategically placed developing states.

I had already had a couple of weeks’ leave to decompress after the numbing stress of my time as Intelligence Officer FRU and was readily anticipating the challenge and variety of something new after nearly six years’ almost unbroken service in Northern Ireland.

I thought the course title was rather grandiose and stretching a point as, in my book, Special Duties meant service in the Province, after tough selection and training with either 14 Coy or the FRU. There certainly was no element of competitive selection that was apparent to me for Mission service and, as far as I could make out, no one ever failed the course. I preferred to refer to the training as the BRIXMIS course. Anyway, moot points, I suspect. In reality, the fact was that BRIXMIS was by then already forty-three years old and had trademarked the term long before. Leaving unit snobbery and arrogance behind, I concentrated on the job in hand.

I am sure I am right in saying there were still two courses run per year. They now lasted four weeks, but earlier courses dating from their inception in 1972 had been shorter. Even though members from the other two Missions blistered onto our training en route to Berlin – there was agreement to put four USMLM students every year on the course – the throughput in BRIXMIS did not require a larger number of new personnel to be trained, and Attaché Branch had other core ‘customers’. By the time the last training package had run its course the following year, a total of forty-nine had been run. That is an impressive record.

We were, therefore, the next and newest generation of ‘tourers’ in every sense of the word. We were from an eclectic mix of backgrounds. There was Martin, a fellow Int Corps officer and Russian interpreter – we became even closer friends in post-Army days as we both worked for Philip Morris International and later on a project based in DR Congo; Steve Gibson, a good friend and a sound operator with much too keen a brain for intelligence work, or indeed for the Army, who went on to write the definitive book on Mission touring and was a key figure in writing up the official history of BRIXMIS; Gary, an ex-Royal Marines SNCO who had passed selection and was badged SAS; Alec, an ex-Guards SNCO who had a long pedigree with 14 Coy and was what was referred to as ‘permanent cadre’; Sinclair, an Int Corps SNCO who came to work directly for me; a handful of others including the newest crop of Royal Corps of Transport drivers; and Jim and Bob, two US officers who were bound for USMLM. Jim was a US Marine Corps officer. He had joined as a weapons officer/navigator flying on Phantoms but had had to bale on that because he suffered from incurable air sickness. And Bob was a US Army officer. I became good friends with both, as much as you can with Americans – and I certainly do not mean that in any pejorative sense, just a feeling I have; I think you only ever get truly close if you marry one and this was never an option. Once settled in Berlin, we socialised together, and I enjoyed the fresh ideas and perspectives each brought to military and civil life there. As a wider point, I always enjoyed every contact with our American opposite numbers, work or socially related, and took every opportunity to understand their operational and tradecraft approaches and compare and contrast them to our own.

Everyone on the course was a good guy. In fact, just about everyone in the Mission, including USMLM, was a decent human being and good to be with at work or play. Given language limitations – theirs, of course, not mine – I did not get to know any of my French opposite numbers that well, but they always struck me as very solid and professional, getting each job done and moving on to the next without fuss or drama.4

The course was intensive, hard work, but lots of fun. Like the courses run across the parade square at the ‘Manor’ in the Specialist Intelligence Wing (SIW), there was no bullshit, no ‘us and them’ posturing between directing staff and students, just a positive sense of professionalism and purpose. The attitude was ‘We know where you are going, what you will be doing, and we will prepare you as best we can so you can accomplish those tasks.’ In my book, there is no other way to conduct or structure training; training is strictly functional with one aim and one aim only. I knew most of the teaching staff from periodic visits to SIW back from the FRU – Templer Barracks was always a small, intimate place. They shared backgrounds either in BRIXMIS or as former defence attaché staff. One of the RAF officers had served on the air attaché staff in Moscow and had flown one of the fleet of Victor tankers that had refuelled the Vulcan bomber that had successfully bombed Port Stanley airfield during the Falklands War, dealing such a powerful psychological blow to the Argentine invaders – a truly amazing operation.5

The first part of the course was entirely classroom based. There was an incredible amount of ‘death by slide’ simply because we had to learn to recognise the whole Soviet arsenal, main variants included (and the Russians loved variants) literally every piece of equipment that was deployed by both the Soviets and the East German NVA in the DDR, and every system that could be moved into theatre, even if only on a temporary basis. This included everything that flew, whether it was a fighter, a bomber, a transporter, a helicopter or anything else. It included every ground-to-air missile, its launcher and associated missile trans-loader, radar, and every rocket launcher and every rocket, including the range of nuclear-capable systems. There was a host of artillery pieces to get under one’s belt, not just towed guns but self-propelled tracked ones and anti-aircraft weapons. Then, of course, there were all the various tanks and tracked and wheeled armoured personnel carriers (APCs) that a tour might see deployed out and about in GSFG’s tactical area of responsibility, communications equipment and communications intercept equipment. And then, just when you thought you had won, a host of trucks – big trucks, small trucks, long trucks, short trucks, trucks with trailers and without – cranes, vans, jeeps et al. Literally hundreds of bits of ‘kit’, a great word and so evocative in the unit – a tour would spring into action at any sighting of equipment spurred by the battle cry of ‘Kit!’ We even looked at some ships because Mission tasking also included some naval targets up on the north coast centred around infamous places like Peenemünde where the V1s of the Second World War had been tested. To spice the process we were also subjected to the subtleties of ‘tarpology’, studying and learning the outlines and profiles of equipment being moved under the cover of canvas tarpaulins to enhance their security and environmental protection. This was obviously a less exact science but a necessary skill if our collection efforts were to be maximised. To add realism, we were tested on long-range views of equipment, close-up detail and views that were partial and involved significant parts of the system being obscured or concealed – just like they would be out on a cold, wet, foggy, grey training area with light levels dropping and dusk descending.6

Beyond equipment recognition, we were taught the significance of a sighting of a particular piece of equipment, not just in isolation but what it was that the sighting signified in terms of its subordination to a formation. Why was it there, what was it doing, and what might be happening around and beyond it? We needed to be able to furnish instant answers. We had to understand at what formational level these weapons systems were operated, and the import of certain sightings and combination of sightings. Ultimately, the question we constantly posed out on the ground sitting comfortably, or uncomfortably, in our G-Wagens was, was there scope and requirement to push up against and beyond the routine collection envelope? This always brought us back to the quintessential challenge of assessing risk versus gain. I have never liked the term ‘expert’, but everyone had to become, of necessity, very, very quietly and demonstrably proficient.

Normally, the prospect and reality of being sealed inside a military classroom hour after hour and day after day, tomb-like, would be met with at least raised eyebrows if not declarations of intent to go AWOL, absent without leave. Frankly, however, I enjoyed the novelty. It was just pleasant to be sitting down comfortably in a warm, dry classroom. I found it therapeutic, after the nuances, subtleties, stress and complexities of agent-handling work, to be either unequivocally right or unequivocally wrong with absolutely no shadings of grey or room for comment, debate or interpretation. Either it was a 2S-3 or it wasn’t. I enjoyed the challenge of assimilating this massive amount of data and then demonstrating that knowledge, pub quiz-like.7 I also appreciated the novelty here getting up every morning. It was a bit of a pain shaving every day, but in contrast to having to decide whether today it was this pair of jeans or that pair of jeans, this T-shirt, that T-shirt or that shirt or jumper, it was so straightforward to put on those same green lightweight trousers, that same green combat shirt, that identical green woolly-pully with those green socks and those black combat boots before heading down to breakfast.

With this arduous initial phase over, the practical part of the course commenced. It dealt with photography, the skill that underpinned everything the Missions did, the tactics of touring and the operational skills required to tour effectively, securely and efficiently to collect the intelligence we would be tasked to gather once on mission in the east.8

I think I took things a little for granted because my short career to date had been entirely operationally focussed. Where some of my fellow students might have faced this phase of the course with some trepidation, I had already spent a year in Northern Ireland with the infantry operating in County Armagh, as well as my time with the FRU, and I’d completed a long covert surveillance course. Hopefully without sounding arrogant, I was fortunate to be confident out on the ground with enough experience under my belt to handle most intelligence collection challenges.

So we made Ashford our Potsdam and toured out against ‘enemy’ targets to our west and north and east. We did not need the Red Army or the NVA. We hit Army static installations and exercise played on and around Salisbury Plain, including the big garrison towns of Bulford, Warminster and Tidworth. We ‘attacked’ the aircraft test site at Boscombe Down and, slightly more chillingly, the Defence Science and Technology facility at Porton Down. And we toured against NATO air targets on the flatlands of East Anglia.

The key lesson the newcomers to clandestine operations learned very early was the requirement and supreme importance to ‘know the ground’ – this maxim underpins operations whether they be agent handling jobs or surveillance tasks or the reconnaissance tours that we were to mount. A sound knowledge of the geography gives an enhanced edge to operational efficacy. Without the need to be constantly head-down in a map book meant one could capture maximum detail and maximise intelligence collection, but beyond that, it increased situation awareness, which directly translated into enhanced security. It was unlikely we would draw enemy fire here, but that was certainly not a given where we were all going in only a matter of weeks. That said, however, the ability to map read well was essential, but when close in to a target, there was no substitute for feeling at home – I have had the conversation multiple times when tourers have stated, without embellishment or exaggeration, that they got to know some areas of the DDR better than those around their own homes. Nothing beats the experience, in this context, of having visited a location before, but without this luxury, proper preparation was paramount. When we arrived in Berlin, preparation for each tour would entail detailed study of the target packs that existed and had been compiled and amended over the long years of previous intelligence attacks. This confidence and ease distinguished the good tourer and the good tour from the average.

The reality of Mission life was that there were of course no allusions on either side as to what each other’s ‘liaison staffs’ were really doing. We knew that SOXMIS and the other two Soviet Missions in western Germany were engaged in intelligence collection, and the Soviet forces of GSFG and native DDR formations of the NVA of course knew the French, US and British Missions were mounting collection efforts against their armed forces and military installations. The name of the game was to not be caught flagrantly, especially on film, in the act of collecting this intelligence. The aim was to refrain from taking undue interest in a military target when this could be observed, especially by a Soviet or East German NVA, military ‘bystander’, a Stasi surveillance operator or even a member of the public – we presupposed, worst case, that all civilians, as good SED party supporters, might report our activities to the authorities.

This necessitated tours to employ stealth as their default guiding principle when tackling a target. Apart from the requirement to remain ‘downwind’, these were essentially the tactics of the hunter. We were stalkers, in the traditional, purist sense. We practised use of covered approaches, minimising noise and observing from cover, invariably from a position standing off from the target. We made full use of camouflage, the most practical manifestation being that the Mercedes G-Wagen could be easily mistaken for the ubiquitous UAZ-469 Russian jeep. But when the situation required it, a final high-speed, aggressive closing with the enemy, then rapid withdrawal was not an uncommon tactic.9

Course exercises tried to mirror as closely as possible the profile of touring for real. In the case of the longer ones, at the end of each day the crews would cook and then bed down in a wood or copse for a few hours of sleep before the next day’s exercise serials. It was not important to extend activity beyond a single overnighter, so we were never away from Ashford for too long.

In the event the Soviets considered a tour vehicle was paying undue attention to their presence, they could ‘detain’ it. This meant essentially ‘arresting’ the vehicle and its occupants. Detentions could be rough and tense and might entail a tarpaulin being thrown over the vehicle to deprive the occupants of any further view of their immediate surroundings, and to intimidate them. Let’s not forget that all our various contacts with the soldiery and citizenry within the DDR were underpinned by the very real reality that we were sworn enemies and the Cold War was ultimately a potential struggle to the death of two civilisations with fundamentally opposed philosophies and approaches to all aspects of life. However, detentions would only be of relatively limited duration, and tensions at this micro level would always eventually subside; the brief to teams was to refrain from taking any action that would escalate matters. Observation equipment–cameras, binoculars, night-vision devices–mini tape recorders, map books and all the other tools of the trade would be packed away, and tourers would assume the attitude of disinterested ‘tourists’ or, rather more pertinently, fully accredited and official ‘liaison officers’. If vehicle doors remained locked, there was nothing the Soviets could do to compromise the tour members, but there had been occasions right up to the recent past when tourers had been pulled out of vehicles and beaten, and equipment had been grabbed and taken. Ultimately, tempers and reactions were governed and directed by the cover the Missions enjoyed as diplomatic entities, but in the same way that diplomats can be persona non grata (PNG), particularly effective tour officers had been targeted for repeat detentions so their expulsion could be justified. Essentially, governing relations was the appreciation that the treatment received by one side’s Mission’s tour would be meted out in reciprocity to the other.

In most cases detentions created opportunities for contact and low-level liaison between the two sides. Eventually, the Kommandant from the nearest Kommandatura would arrive to take charge of the incident. He would attempt to get the tour to sign an ‘Akt’ admitting they had been engaged in improper activity and/or were in an area where they were denied access, which of course tour officers refused to sign. All Mission crews carried detailed mapping accurately displaying PRA borders, which were religiously and promptly updated when revisions were made. Invariably, the Soviets would argue the case for Mission tours to be in a PRA on ridiculously small-scale sheets upon which the width of a pencil line represented several kilometres. These were invariably uneven debates. By implication, however, the very existence of the Akt suggested that on some occasions they were, or had been, treated with respect and a signature, but certainly by 1989, no more. Eventually, the tour would be released, generally after an imposed rest period of several hours, and let go, to continue its collection mission – all a merry little dance.

Long story short, we were subjected to a detention on the course at some stage during one of the exercises, complete with character players dressed in Russian uniforms and with exchanges in Russian. The charade was a useful little tutorial but provoked none of the real-life angst and drama that could accompany the real thing. I was detained later in Halle and I have to say the lessons identified by our mock arrest did prove useful, but ultimately the knowledge that, barring a freak accident, you were not going to be hurt or unduly stressed made detentions little more than interesting and novel distractions. A few years later during the Kosovo War, I was in the far north of Albania, heading up to the border with Kosovo and was hijacked by heavily armed bandits. This was a rather different deal, a little more stressful and a little less controlled and predictable in its outcome. But the same basic approach ensured this experience had an equally happy ending. An important lesson of life is always to attempt to engage an aggressor in conversation, the calmer and more rational the better. Someone talking to you is unlikely to be someone engaging in simultaneous acts of violence against your person.

The ground tours we practised gave me the opportunity to see a bit more of my Army, but the most interesting to me were our runs to target the USAF air bases up at Lakenheath and Mildenhall. Air tours complemented the Missions’ ground-related activity. They too were terrestrially mounted, but not exclusively as I will explain later. The ‘air’ aspect of their nature meant targeting aircraft, radar and air defence equipment. Against Soviet Air Force targets, this related to observing both the tactical deployment of systems and the deployment of new equipment, typically underslung bombs and missiles, newly deployed radars and associated hardware and surface-to-air missiles (SAMs). Resultant photography of course identified and confirmed new kit but it had to be of a quality and resolution that allowed analysts to extract technical intelligence. This entailed tours targeting Soviet aircraft by attempting to get in position at some point along an airfield’s centre line to observe and photograph the underside of the planes on final approach, coming in to land, when flight speeds were at a minimum and the configuration for landing provided ideal observation opportunities.