9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

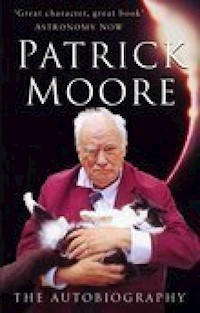

Throughout his distinguised career, Patrick Moore has, without a doubt, done more to raise the profile of astronomy amoung the British public than any other figure in the scientific world. As the presenter of The Sky at Night on BBC television for nearly 50 years he was honoured with an OBE in 1968 and a CBE in 1988. In 2001 he was knighted 'for services to the popularisation of science and to broadcasting'. The BBC first aired The Sky at Night in April 1957 and it is now in the record books as the world's longest running TV series with the same presenter. He is also the author of over 60 books on astronomy, all of which, including his autobiography have been written on his 1908 typewriter. Partly thanks to his larger-than-life personality, Sir Patrick's own fame extends far beyond astronomical circles. A self-taught musician and talented composer, he has displayed his xylophone-playing skills at the Royal Variety Performance and as a passionate supporter of cricket, he has played for the Lord's Taverners charity cricket team.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

Contents

Title

Foreword to the New Edition

1The Kid

2The Reluctant Teacher

3The Craters of the Moon

4Facing the Cameras

5Pioneers

6Here and There

7Irish Interlude

8Moon Missions and Moon Men

9How’s That?

10Tally Ho!

11Mars Hill

12Xylophones and Transits

13The Return of the Comet

14Chasing Shadows

15The Grand Tour

16O Argentina

17Vote, vote, vote?

18The Battle of Greenwich

19Crazy Consignia

20The Weak Arm of the Law

21Globe-trotting

22The Tale of Mr. Twitmarsh

23The Power of the Press

24Apollo – and After

25Coasting Along

26Indoor Stars

27Winding Down

Plates

Copyright

Foreword to the New Edition

When my autobiography, Eighty Not Out, burst into print in 2003, I had no idea what to expect. If it attracted any comments at all I rather thought that there would be attacks from people who disagreed with me, notably the fox-hunters and the Politically Correct fanatics. Yet this didn’t happem.

The first Press interview, with a middle-aged Times reporter (a Miss Penny Wark) was not very encouraging, she came down to see me, didn’t get the answers she may well have wanted after her oft-repeated questions and departed looking furious (at least, I thought she looked furious, it may of course have been her natural expression). But subsequent Press reporters, notably from the tabloids, were uniformly friendly and courteous; so too were the radio and TV interviewers. I felt reassured. And most of the stack of letters I received were on my side; the few broadsides from the fox-hunters were always anonymous and usually obscene!

I haven’t really much to add; I have made a few amendments and put right some errors which slipped through my proof-reading, but that is all. If you read the book through, you are bound to find things with which you strongly disagree, but I always say what I genuinely think, so that at least everybody knows where they stand with me. If I were ten years younger and physically fit, I would now be gearing up for the next General Election and putting my name forward as a candidate on behalf of UKIP; as things are – well, I will go on doing what I can as long as I can. Best wishes.

Patrick Moore

Selsey, December 2004

1

The Kid

On several occasions I have been asked to write an autobiography. I can’t imagine why. I am not a teenage footballer, a pop star or a rock legend; I am an ancient astronomer. If the total sales of this book amount to fourteen copies, I will not be in the least surprised. However . . .

I am going to gloss over my first years very briefly. I was born on 4 March 1923, so far as I know. My birth, unlike Glendower’s was not accompanied by any celestial manifestations. My father, Charles – more properly Captain Charles Trachsel Caldwell-Moore, M.C. – was essentially a soldier; he died in 1947. My mother, Gertrude – née White – was trained as a singer; of her, more anon. Brothers and sisters had I none.

I grew up first in Bognor Regis and then in East Grinstead, both in Sussex. I was destined for Eton and Cambridge, but never made either, because a faulty heart laid me low for much of the time between the ages of six and sixteen, and there were long spells when I could do very little except read. However, when I was eight I did manage a full term at prep school. I enjoyed it, but not all of the activities were successful. My mother was a talented artist, but this was something which I did not inherit. We had art once a week, taken by a Mr Moore. On one occasion I was given some art prep, and was told to draw a towel hanging over a chair. I misheard, and thought that I had been told to draw a cow hanging over a chair. I did so. My mother kept that drawing for years; I wish I knew where it is now. Mr Moore then wrote, saying that I was commendably keen, but on the whole wouldn’t it be better if during art lessons I went and played the piano in the music-room? My art career ended at that point.

Carpentry was no better. It was taken by a master whose name was (honestly) Mr Wood. The boys were asked what they wanted to make, and chose the usual items, such as letter racks and hatstands. I elected to make a boat, so I was given a chunk of wood and told to hollow out the hull with a hammer and chisel. By the end of the term all the other boys had finished their letter racks, but I had not even completed the hollowing-out process, and had put the chisel through the bottom so many times that the entire project was abandoned. Career number two lay in ruins.

As you will gather, manual dexterity was not my forte, as was evident from the outset. I do not actually qualify as being dyspraxic, but I have to admit that I am fairly close to the borderline; for one birthday I was given a tool set, and it took me exactly ten minutes to hammer my thumb. (Things are no better today. Quite recently I was trying to fix a tin-opener to the kitchen wall when someone told me, kindly, that I was putting it in upside-down. I was).

That one term at prep school proved to be a false dawn, and it became clear that Eton was ‘out’. I passed the usual school exams, with the help of tutors, and was geared for Cambridge when the war started. I manoeuvred my way into the forces – I have to admit that with regard to my age (sixteen) and physique I was decidedly economical with the truth – and that put paid to university. The other day I happened upon a photograph of a very young Patrick Moore in the uniform of an RAF officer. Looking at it now, I can understand why in those far-off days nobody ever called me anything but ‘the Kid’.

What else? – Well, I did have a rather interesting war, but it was long ago, and a great deal of water has passed under the bridge since then. At the end of it I still had my Cambridge options, but it would have meant taking a Government grant, and this did not appeal to me. I prefer to stand on my own feet (size thirteen), so I meant to take up my place as soon as I could afford it. In the event, I never had time, because astronomy took over. I became ‘hooked’ at the age of six, simply by reading a book, The Story of the Solar System by G.F. Chambers, published in 1898 at the exorbitant price of sixpence. I was lucky; a family friend proposed me for membership of the British Astronomical Association when I was eleven, and I was duly elected. (Exactly fifty years later, I became President). In 1952 I was invited to write a book, and I did so: Guide to the Moon. It was published a year later, and so this seems to be a rather good place to begin my narrative . . .

2

The Reluctant Teacher

There are two reasons for beginning these notes in 1953. One, as I have said, is because it was the year in which my first book came out. The second is that this was the year when I definitely abandoned all ideas about taking a conventional job. I was determined to go my own way.

At the end of the war I had no official qualifications – apart from the ability to fly and navigate a turboprop plane – and I had no financial backing at all. My father died in 1947. He and I were quite different people; had he been able to stay in the Army instead of being forced to retire because of a lungful of German gas swallowed in 1917, he would undoubtedly have ended up as a general, whereas nobody could be less military than I am. I was exceptionally close to my mother, who was with me until the day she died: 7 January 1981. One thing was certain: marriage was ‘out’. Please do not misunderstand me. I was a perfectly normal boy, I became a perfectly normal young man, and today I am a perfectly normal old man. But Lorna, the only girl for me, was no longer around, thanks to the activities of the late unlamented Herr Hitler; in fact she hadn’t been around since 1943. Quite recently, someone asked me whether she was ever in my mind. I replied that after sixty years there were still rare occasions when I could go for a whole half-hour without thinking about her – but not often. This explains why I am a reluctant bachelor, and also why I know that if I saw the entire German nation sinking into the sea, I could be relied upon to help push it down.

When Hitler, the Wops, the Nips and the Vichy Frogs had been disposed of, I had to take some personal decisions. Suddenly, instead of having a great deal of responsibility, I had none at all; a curtain had been dropped, and I was still in my early twenties. My Cambridge place was still there, but I could not overcome my distaste at applying for a Government grant; perhaps illogically, it went against the grain. I was brashly sure that I could write, and that eventually I would earn enough to pay my way through university. At least I could type – and thereby hangs a tale.

When I was six, my grandfather’s 1892 Remington typewriter was found in our loft at East Grinstead, and was passed to me as a plaything. Instead, I taught myself how to use it, and I still have it, in full working order; in my will it is left to the Science Museum, where its twin is. Two years later I acquired a 1908 Woodstock; I believe it cost half a crown. By then my ‘bible’ was W.H. Pickering’s book about the Moon, which had been published long ago and was quite unobtainable. A family friend who had connections with a science library in London managed to borrow a copy, and it was in my possession for a month. I remember thinking: ‘If I type it out, I’ll have the book I want, I’ll be able to type quickly, and I’ll be able to spell.’ It worked like a charm; after 60,000 words I was touch-typing with no difficulty at all. That typed copy is in my study now.

That Woodstock has served me ever since, and all my books, including this one, have been written on it. Mind you, changing a ribbon is quite a business; you have to get a modern ribbon and wind it on to the old spool, a procedure which has to be done about once a week. I have battled with an electric typewriter and even with a word processor, but with a total lack of success. (Not long ago NASA asked me to write a chapter for a book they were publishing about the Moon. I complied, and was sent a reply: ‘Thank you for your chapter. This is exactly right, and will go straight to press; moreover, congratulations – you are the first author to send in his material.’ And in ink, at the bottom of the letter, a query: ‘What the . . . ing hell did you type it on?’)

Writing it would be, but meantime a job was essential. My mother had a modest income, but I did not have the slightest intention of living on that, so a job it would have to be.

The only thing that seemed possible was teaching, so I applied for a post at a boys’ prep school, and was accepted. I was sure in my own mind that I was not cut out to be a schoolmaster, but teaching occupied me for the next few years, first in Woking and then at Holmewood House in Tunbridge Wells. Holmewood was new, and when I arrived the total complement was around a couple of dozen boys, aged 8 to 14, and half a dozen adults. John Collings founded the school, and was headmaster; his wife Mary was there, of course. My fellow members of staff were Jo Oldham, circa sixty years old and Alexander Helm, known to most of his friends as Sandy, but to just a few as ‘Elm’ – because he was once pompously announced by the old school butler as ‘Mr Elm’, and the name stuck. He became, and has remained, a very close friend indeed; I was best man at his wedding to Paddy (sadly, no longer here – cancer claimed her) and am godfather to their daughter Pippa.

Setting up a new school must be a pioneering process, and it was certainly true at Holmewood. We were all very close, and as John Collings was not fit – again, due to war service – there were times when Elm and I found ourselves running the show. Once I even had to do the school accounts. The Army had owned the house and grounds before John bought them, and there was a ha-ha round the boundary – a ha-ha being, as I am sure you know, a ditch with one vertical wall, so that it can’t easily be crossed. We had no use for it, so we ordered cartloads of soil and filled it in – we had no shortage of boy volunteers, it was that sort of atmosphere. In the accounts I entered ‘Dirt for ha-ha, £40.’ The auditor marked it ‘Ha-ha to you’, and sent it back!

I won’t dwell on the school years, because I never intended to make teaching a career, and I would have left Holmewood well before 1953 had not John particularly asked me to stay on until everything was really firmly established. In fact I enjoyed my time as a teacher, and I do genuinely think that the boys knew we were there to help them on their way to their public schools. I am still in touch with many of them – and of course some of them have now retired, which is a shattering thought and makes me feel very antique. Four years ago I was in New Zealand, and went to stay for a week with a former pupil, Robert Crawford, whom I hadn’t actually seen for a long time even though we corresponded regularly. I think I half-expected to see a twelve-year-old rather than one of New Zealand’s most senior and respected surgeons. Tempus fugit . . .

Quite a number of Holmewood episodes remain fresh in my memory, by no means all of which would appeal to the modern Politically Correct fanatics and the crackpot child psychiatrists. For example, there was some mysterious creature, which persisted in digging holes in the cricket pitch. We christened it Hubert, and set out to identify it. We put sand round the hole to see if we could find any traces; next morning there were little fairy footprints in the sand – no boy ever ‘came clean’, though I always had a shrewd suspicion as to the identity of the culprit (I really must remember to ask him next time we have lunch together). Finally we decided upon drastic action. Around 5 November we packed the largest hole with gunpowder, covered it up, and left a trail of powder in the direction of the cricket pavilion. Watched by a crowd of boys, we lit the trail. Fire made its way along the grass, and then into the hole. It was much more violent than any of us had expected, and it was lucky that we were far enough away to dodge flying debris. When all seemed to be quiet we uncovered the hole, which was now so deep that one of the boys wondered whether it would reach through to Australia.

There was no sign of Hubert. Next morning there were six holes in the cricket pitch, and we admitted defeat; Hubert had won hands down. He, or she, or it, was never identified.

I also remember the swimming pool, which we dug with volunteer labour (again there was no shortage of recruits). In the end we had a good pool, suitably lined, refilled every week with water drawn from the mains. Of course it wasn’t used in winter, and at the start of summer term we realized that it was (a) full to the brim with green slime on the top, and (b) the plug was in the plughole, with no cord. What to do? We held a poolside conference. Someone, clearly, had to dive in and get the plug out. Elm, who is a very strong swimmer, was not there for some reason or other, and I firmly opted out, because I can barely swim at all. Bill, aged thirteen, came to the rescue. Watched by an admiring host, he stripped off, held his nose, and jumped in. Nothing happened, and I was just wondering how to break the news to his parents when he reappeared, brandishing the plug before clambering out to a round of applause and squelching off toward the showers. To say that he smelt was the understatement of the century . . .

We did not have a strong religious atmosphere at Holmewood, but officially the boarders were scheduled to go to the local church each Sunday. Somehow or other this never seemed to happen; either it was too hot, or too cold, or urgent cricket practice was needed, or else whoever was due to take church parade had a headache. Eventually the Vicar volunteered to come and take a service in the school dining hall. He was very anxious to have a lectern and a dove of peace. We rustled up a lectern – a prop from one of the school plays – a dove was beyond us. Then one of the boys produced a plastic pterodactyl, and we set it up. I have to admit that it was an evil-looking beast; it leered at you, and I can still see those eyes even now. The Vicar did not regard it as suitable, and went so far as to suggest that we were not taking him seriously enough. Still, we had done our best.

Cricket was always a major sport at Holmewood (it still is), and on Sundays we occasionally fixed up matches against local teams. Some of the older boys were always keen to play, and they were pretty good (both Jo Oldham and John Collings were excellent batsmen, and they coached well; I was less useful, because I was purely a bowler, with an unorthodox action). One evening, after a match, some prospective parents were being shown round the school. Three or four boys were relaxing on the field, and one of the visitors commented that they looked very peaceful. In fact they looked rather too peaceful, and I knew that some cider had been left in the pavilion. Tactfully the parents were steered clear, and subsequently the boys were ushered to their dormitories, very sleepy but with no obvious signs of hangovers. Of course, they had thought that they were drinking something as innocuous as lemonade – and as one of the boys had made an excellent thirty in the match, it was perhaps understandable.

I do not want to give the impression that there was no discipline. There was plenty; for example there was a definite policy about bullying, which amounted to what we would now call zero tolerance. It was accepted that any boy caught bullying would be rather disinclined to sit down for the next hour or two, and the predictable result was that there was no bullying at all – something which would surprise the modern ‘do-gooders’ who have done such immense harm to our whole educational system.

I have said that I do not propose to dwell on school days, but I cannot pass on without referring to that well-known poet L.F. Antyne. At one stage the boys had been reading poems by T.S. Eliot and came across the immortal lines:

The sunlight shines on Mrs Porter,

And on her daughter,

They wash their feet in soda-water.

We decided that if Eliot could get away with this sort of verse, so could we, and we invented Antyne. Jo Oldham was superb at this sort of thing, and Antyne poetry became all the rage; it spread like wildfire, and one could not open a boy’s English book without finding a new Antyne poem. One which became popular was entitled ‘Futility’. I think I wrote it; it may have been a combined effort – anyway, here it is:

The deep futility of ephemeral things

Which stir the soul to unimagined dreams

Of Brussels sprouts, and spinach in the snow.

The birds’ shrill call in the translucent dawn

To embryonic beetles, and pale moths

Which hide their heads in shallow troughs of earth,

Naked and fearful, as the world awakes

To thought transcendent life, and cosmic death.

The earthworm, crawling to his nameless tomb

All energy dispersed, to form new creeds

New auras of the spirits of the wild,

In the deep pool of life, which ceaseless flows

Through endless time and space, in rhythmic praise

Of all creative impulses, which dwarf

The puny concepts of the human mind.

All, all, shall pass into oblivion . . .

How sad!

A difficult situation arose when a modern poet came down to give a talk. One wretched boy stood up, read out some Antyne poetry, and asked for comments on it. The poet proceeded to tell us what it all meant. Keeping a straight face was no easy matter, but we managed it, and I must admit that the boys, played their parts well; not one of them giggled.

As 1953 drew on, I had to make another decision. I had had my first book published, and interesting things seemed to lie ahead of me – Cambridge or no Cambridge? Things at Holmewood were stable, there was quite a staff, and the numbers of boys were increasing all the time. I was no longer needed, as frankly, I had been in the pioneer days. So, at the end of the winter term I produced the school plays for the last time, made my farewells, and jumped out into what was, for me, a new and unchartered world.

3

The Craters of the Moon

From 1953 onward, astronomy dominated my life, so I think I must backtrack a little to set the scene. Of course it goes back to the time when I read that little book by G.F. Chambers, and I think I tackled it in the right way.

I did some more reading, obtained a simple star map and learned my way around the night sky, which isn’t difficult if you put your mind to it; I made a pious resolve to learn one new constellation on every clear night. Next I borrowed a pair of binoculars, and investigated objects such as double stars and star clusters. By the time I was eleven, I had saved up enough money to buy a small telescope, and I had two slices of luck. One was to be elected a member of the British Astronomical Association; I well remember being taken to a meeting in London, at Sion College, and having the strange experience of walking up to be admitted by the President, at that time Sir Harold Spencer Jones, the Astronomer Royal. It never occurred to me that half a century later I would myself occupy the Presidential chair.

The other slice of luck was that I met W.S. Franks, a well-known astronomer who lived in East Grinstead and ran a private observatory owned by F.J. Hanbury, of the firm of Allen and Hanbury. Brockhurst Observatory was within a couple of hundred yards of my home, and was equipped with an excellent telescope – a 6-inch refractor. Franks took me under his wing, and taught me how to make astronomical observations. He was in his eighties, and just about five feet tall; he had a long white beard and always wore a skull-cap, so that he looked exactly like a gnome. He was a most delightful man, and it came as a very nasty shock when he died suddenly following a road accident; a car knocked him off his bicycle which he rode every day between his home and the Observatory.

To my intense surprise, I was invited to take over and run the Observatory. For a fourteenyear-old this was a great opportunity, though I have to admit that my main duties were limited to showing astronomical objects to the Brockhurst house guests (Hanbury was mainly interested in growing orchids!). I hope that I acquitted myself well, and of course I had full use of the telescope. My first paper to the BAA was presented during this period; it dealt with features on the Moon, and was entitled ‘Small Craters in the Mare Crisium’, based on my own work. I sent it in, and was notified by the Association’s Council that it had been accepted, but I felt bound to explain that I was not exactly elderly. I still have the reply, signed by the then secretary, F.J. Sellers: ‘I note that you are only fourteen. I don’t see that that is relevant.’ I duly gave the paper, though I imagine that some of the members present at the meeting were distinctly surprised.

For obvious reasons my next paper was delayed until after the war – I had other things on my mind – but afterwards, while at Holmewood, I set up a telescope at East Grinstead. It was a 121/2-inch reflector, for which I retain great affection and which is now in my garden in Selsey, protected by a run-off shed. I began regular work, and joined the Lunar Section of the BAA. The Moon was always my special interest, and at an early stage I made a discovery which turned out to be much more important than I realized at the time.

As I am sure you know, the Moon is the Earth’s satellite, and moves round us at a mean distance of just under a quarter of a million miles, which astronomically is on our doorstep. It takes 27.3 days to complete one orbit, and it spins on its axis in precisely the same time, so that it always keeps the same face turned toward us; from Earth, there is a part of the Moon which we can never see, because it is always turned away from us. There is no mystery about this. When the Earth and the Moon were formed, about four and a half thousand millions years ago (I was away at the time), both were viscous, and raised tides in each other. The Earth is eighty-one times as massive as the Moon, and so its tidal pull was very strong. In fact, the pull of gravity tried to keep a ‘bulge’ in the Moon facing Earthward, and this slowed down the lunar rotation, rather in the manner of a cycle wheel rotating between two brake shoes. Eventually the rotation relative to the Earth (though not relative to the Sun) stopped altogether, and the ‘far side’ was rendered unobservable, to the intense annoyance of astronomers such as myself. However, for reasons which need not concern us at the moment, there is a slight, slow wobbling to and fro, so that all in all we can examine a total of fifty-nine per cent of the lunar surface, though of course no more than fifty per cent at ony time.

The edges of the Earth-turned face are very foreshortened. The Moon is covered with mountains and craters, together with broad grey plains which are always called ‘seas’ even though there has never been any water in them (thousands of millions of years ago they were filled with lava). Most craters are circular, but when seen near the limb (the Moon’s edge) they are foreshortened into long, narrow ellipses and are by no means easy to map.

My personal programme was to study these regions, and do my best to chart them, using my 121/2-inch reflector. This involved making drawings, and one small incident sticks in my mind. I had come in from the observatory, and was making a fair copy of a sketch, using Indian ink. I had a cup of coffee by me, reached out, took what I thought was the cup, and gulped. Have you ever tasted Indian ink? I don’t recommend it, and it is also very difficult to clean it away from your teeth.

One evening at the telescope I happened upon a feature which was not on the official maps, and which seemed to be the nearside edge of a ‘sea’. It came into view only when ideally placed, as it was on that occasion. I telephoned H.P. Wilkins, Director of the BAA Lunar Section, who went to his telescope (a 15-inch reflector) and obtained confirmation, so that we could alert our best photographers. It turned out that the feature was indeed a ‘sea’, but an unusual one; a huge ringed structure extending on to the Moon’s far side. This became clear only in 1959, when the Russians sent an unmanned space-craft, Lunik 3, on a round trip and secured the first direct views of the hidden regions.

I submitted a paper to the Association, and suggested a name for the feature: Mare Orientale, the Eastern Sea, because it lay on the east limb of the Moon’s face as seen from Earth. This is what we call it today, though an official edict in 1967 transposed east and west – so that my Eastern Sea is now on the Moon’s Western limb.

I was also concerned with what I christened TLP, or Transient Lunar Phenomena, which seemed to be due to gases sent out from just below the Moon’s surface layer, disturbing dust and producing elusive glows or obscurations. They are very mild, and for a long time their reality was questioned, but they do exist. Mind you, the Moon is a quiet place; the last major craters to be formed date back at least a thousand millions years, so that the dinosaurs must have seen the Moon just as we see it today – assuming, of course, that they were interested enough to look.

After Holmewood I found more than enough to occupy me. I had to earn my living, and by the end of 1953 I did have two books to my credit; otherwise I would have been wary of going freelance, though my mother was all in favour of it. Guide to the Moon was one of the books; the other was a translation from the French.

I lay no claim to being a linguist. I speak French with a curious Anglo-Flemish accent, and my grammar is not impeccable, but I am fluent enough (when I go to France I take delight in making out that I don’t speak French; some of the comments are most revealing). At one stage I could get by in Norwegian, but now I have forgotten every word. Not that it matters, because all Norwegians speak excellent English.

In 1952, a well-known French astronomer, Gérard de Vaucouleurs, wrote a book about Mars, about which he knew a great deal. He did not then speak English (though he learned it later), and asked me to prepare a translation. I did so, and Faber & Faber in London published it. It is very out of date now, because Mars is not the sort of world we believed it to be fifty years ago, and the marvellous Martian canals have been relegated to the realm of myth. Not that de Vaucouleurs believed in artificial canals or little green men, but he did believe – wrongly, as we now know – that the canals had what he termed ‘a basis of reality’. Actually they do not exist in any form, and were mere tricks of the eye. It is only too easy to ‘see’ what you half expect to see.

But it was Guide to the Moon which really sparked off my literary career, and this again was due to sheer luck. As a teenager I had joined the British Interplanetary Society, which was then regarded as rather outlandish; one early member, whom I came to know very well indeed, was Arthur C. Clarke. When the Society became active again, after 1945, I remained a member, and on one occasion – it must have been in 1950 – I gave a talk about the Moon. By some odd chance a report of that lecture found its way into New York press, and was read by Eric Swenson, head of the publishing firm of W.W. Norton, who was looking around for an author capable of writing a book about the Moon. He checked, and found that I was secretary of the BAA Lunar Section, after which he rang the London publishing firm of Eyre and Spottiswoode. The first I heard about this was in the form of a letter from Robin Warren Fisher, of Eyre and Spottiswoode, inviting me to write a full-scale book.

I was taken aback, but I did realize that this was my big chance, so I sat down in my study, put a new ribbon in the Woodstock, took the phone off the hook, and set to work. For the next few weeks I was seldom seen by anybody apart from my mother and our beloved ginger cat Rufus, who at the age of nineteen was still hale and hearty (it was a sad moment when he finally departed, but at least we gave him twenty happy years). I finished the manuscript, sent it in, and waited anxiously for reactions. I was fully prepared to receive a cold note and rejection slip, but not so; the publishers – both in London and New York – were enthusiastic, and the book went straight into production. It turned out to be a success, and was even reprinted before publication, which was decidedly unusual. It ran to eight editions, and is still in print, though now called Patrick Moore on the Moon – a misleading title, because I have not been there. As I have often said, it would take a very massive rocket to launch me into space.

I followed up with Guide to the Planets, and this also sold well. Meanwhile, there was another angle which I tried to exploit: science fiction.

I could read easily by the time I was five, and before long I devoured Jules Verne, H.G. Wells, and teenage periodicals such as Modern Boy, which I remember as being very good even though it would now be regarded as sexist and jingoistic. Why not try my hand? So the Woodstock was put to work, and in the fullness of time I completed my first boys’ novel, The Master of the Moon. It was fun to write, but I did not really expect to see it in print. I selected a publisher by sticking a pin into a list, and sent the manuscript off to Museum Press. They accepted it by return. I doubt if I have ever had a bigger shock.

A copy of the book lies on the desk beside me, and I have to say that its scientific credibility is somewhat questionable. Listen to the words of Professor Quinn as he and his companions prepare for take off:

‘Ought we – ought we to lie down or something?’ asked Jock, gruffly. ‘I mean, are we liable to be chucked about?’

‘Lie down by all means,’ said the Professor. ‘In fact I intend to do so myself, but only as a precautionary measure. The actual start should be no more violent than the sudden ascent of an electric lift.’ He settled his spectacles firmly on his nose, and peered at the complicated instrument panel in front of him. ‘Ready?’

‘Ready,’ echoed Sorrell.

‘Excellent.’ Quinn stretched himself out on the floor, motioning the two boys to do the same and raised his arm.

‘I shall count three, and then push the starting button. One . . . two . . .’

Noel and Jock watched as though hypnotized. For all the emotion he showed, the little professor might have been asking them for a ride on the Brighton scenic railway instead of shooting them into space at seven miles a second. His hand hovered over the panel, steady as a rock.

‘. . . three,’ he concluded, and jabbed.

There was a sudden jerk, and the electric light snapped out, plunging the interior of the rocket into inky darkness. Noel felt as though he were falling into a bottomless pit; yet there was no actual sensation of motion – the walls of the rocket pulsated slightly, and a faint hissing sound could be heard, but that was all.

‘Most annoying’, came Quinn’s voice, irritably. ‘Something seems to have gone wrong with the light. Has anybody got a torch?’

Well, you can see the general idea, and worse was to follow. On arrival the space-travellers find a hollow Moon with a breathable atmosphere; a shining underground lake populated by chirping death-dealing spiders; hideous green cavern-dwellers, and even a villainous Russian who has been there for some time and has declared himself Master of the Moon. Fittingly, the climax comes with a battle with death rays. I enjoyed writing it, and the boy readers seemed to approve, but I doubt whether NASA would view my ideas with much enthusiasm.

In my defence, I plead that when I began to write the novel I had no intention of being scientific; I merely wanted to see whether I could tell a story, and apparently I could. Later on I produced around a dozen more boys’ novels, though after the first two I did make an effort to keep to known facts. It was then suggested that I might try an adult novel. I did so; when it was finished I put it aside for a week, and then sat down and read it through. Sadly, I held it over the waste-paper basket and released. It was no good, and I knew it, so nobody else ever read it.

That was one of the only two manuscripts I finished which never saw the light of day. The other was a farce novel, Ancient Lights, which I wrote in 1954 or thereabouts. Had I submitted it, I am fairly sure that it would have been published, but I had so much to do that I never got round to it. There would be absolutely no point in trying it now, because it belongs to a past age. There are no steamy sex scenes, no four-letter words, no persecuted ethnic minority groups and no homosexuals, while the nearest approach to violence comes when the old archaeologist receives a sharp poke in the snoot. It would also be deemed Politically Incorrect by today’s standards. I still have the only copy in existence!

Most would-be authors find it difficult to break into the publishing world. I did not, but I am the first to admit that Fate was on my side, just as it was when I began my career in television. Not to put too fine a point on it, I had more than my fair share of luck. At least I took advantage of it; had I not done so, I would not now be writing this book.

4

Facing the Cameras

My very first BBC broadcast was made in 1954, in the overseas service. The subject was about Greenwich Observatory, and I was to join the Astronomer Royal. We were ushered into the studio, and just before we went on the air, ‘live’, the producer said: ‘By the way, this is in French. Do you mind?’ Mercifully I didn’t, but if it had been any other language I would have been beaten. I felt that I ought to have been warned.

Television came later. I have often been asked how I managed to break into it, and the answer is that I made no conscious effort at all; the idea came from the BBC, and in particular from Paul Johnstone, a highly respected producer who was also a scientist (not an astronomer, but an archaeologist). So far as I was concerned, the whole chain of events began with flying saucers.

At that time, flying saucers were all the rage. They had first become headline news in 1947, when an amateur pilot named Kenneth Arnold was flying a private plane over the State of Washington, and reported nine round objects, in formation and travelling at high speed, passing within a few miles of him. He said that they were ‘flat, like pie pans’, and the term flying saucer came from this.

Arnold believed that he had seen space-ships from another planet; he also believed that the Authorities (with a capital A) were dedicated to playing down his story and concealing the truth. Before long there were more reports, some of them sensational. If they were to be credited, the Earth was under close scrutiny, though by whom or for what purpose remained obscure. Neither was it known whether the saucers were friendly, hostile or merely inquisitive. Photographs of them were invariably blurred, and their whole behaviour was erratic.

I soon began to receive inquiries. Most of the reports could be put down to mundane objects such as birds, bats and balloons; aircraft, searchlight beams and the planet Venus were other favourites. In the early days I remember being telephoned at three o’clock in the morning by an agitated lady living in East Grinstead, who announced that she had seen a saucer hovering over her garden in a menacing manner. When I asked how it was moving, she replied that it ‘seemed to be flapping’, but I could not convince her that she had been watching a bird on the look out for a breakfast worm.

Where there are space-ships, there must presumably be astronauts, and it was inevitable that there would be reports of contact with alien beings. The spark was ignited by George Adamski, who published the famous book Flying Saucers Have Landed in 1953. His co-author was Desmond Leslie, but Desmond’s section was confined to historical accounts, comments and interpretation, because he had not seen a Saucer himself. The really sensational part of the book was the Adamski account of his meeting with visitors from Venus, which, he told us, took place at 12.30 p.m. on 20 November 1952.

The place was near Parker, in Arizona, actually on the Californian desert. Together with some friends, Adamski saw the saucer; alone, he located the pilot, who was rather like an Earthman but for the fact that his clothing was atypical for a walk in the desert. For instance, he was wearing what seemed to be ski trousers. Also he had shoulder-length hair, beautifully waved. He could not talk English, and he had to communicate in semaphore, but he was able to establish that his home was on Venus. At the end of the interview the Saucer itself came along to join the discussion, and hovered above the ground; inside there were several people. It was in this remarkable craft that the Venusian made his exit, leaving George alone in the desert.

When the book appeared it became an immediate best-seller. I have no idea how many copies were distributed, but it must have been at least a million. George Adamski became world-famous, and produced several more books; on one occasion he was taken for a ride in a Saucer, and soared close to the Moon. I quote:

‘As I studied the magnified surface of the Moon upon the screen . . . a small animal ran across the area I was observing. I could see that it was four-legged and furry, but its speed prevented me from identifying it.’

Meantime, I had come to know Desmond Leslie, and we remained great friends until, sadly, he died not so long ago (January 2002). The flying saucer craze showed no sign of abating for some years, and support came from most unlikely people. Notably Air Chief Marshal Lord Dowding, who had been in charge of RAF Fighter Command during the Battle of Britain in 1940. I knew him well. He believed not only in flying saucers, but also in fairies and gnomes, so that he was hardly typical of a senior RAF officer. Yet it was Hugh Dowding who saved us from losing the war. During the Battle of Britain he did not make a single mistake, which was just as well in view of the fact that we had no reserve aircraft. It was also he who persuaded Winston Churchill not to send any aircraft to France after the evacuation of Dunkirk. In my view Hugh Dowding was one of the greatest Englishmen of the twentieth century, and he never received full recognition for what he achieved at a time when we needed him most.

A television programme was planned. Desmond, Hugh Dowding and a couple of other Saucerers were to present the case in favour of flying saucers, and Desmond asked me to present on the case ‘against’, because he was well aware of my lack of faith in all forms of airborne crockery. The programme was duly broadcast, and was well received. Paul Johnstone produced it, and said that he was extremely satisified.

We went our separate ways, and I thought no more about it until one morning when I had an interesting phone message. Would I go to Lime Grove, at that time the headquarters of BBC television, and talk to Paul Johnstone about a possible programme dealing with astronomy?

I was elated – well, who wouldn’t have been? – and I lost no time in making my way to Lime Grove. It transpired that Paul had been casting around for an astronomy presenter; he had read a book of mine and also studied the Saucer programme, with the result that he thought I might be suitable.

We had a long talk. What exactly was our aim? Could we manage a programme every month, slanted toward the newcomer and yet with enough solid material to entrap the well informed? Paul thought we could, and so did I, though at the time my knowledge of television was effectively nil, and in any case television had nothing like the influence it has today. There was also the problem that astronomy was widely regarded as being practised only by old men with long white beards, who spent their lives in lonely observatories ‘looking at the stars’, and no doubt using crystal balls as well.

Since all this happened more than fifty years ago, I think I must say a little about the situation at that time. In early 1957 the Space Age had not started; it was not until the following October that the Russians launched Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite, which took many people by surprise and caused considerable alarm in America. (One man in Washington rang the Pentagon to say that a sputnik had landed in his garden and was lodged in the top of a high tree; it turned out to be a balloon, with ‘upski’ painted on the top and ‘downski’ on the bottom.) The great radio telescope at Jodrell Bank was only just being brought into action, and was widely regarded by the general public as being a waste of money. The idea of sending a man to the Moon was little more than a music-hall joke, except to those people who had taken the trouble to investigate, while rockets were still associated only with the V2 weapons masterminded at Peenemünde by Wernher von Braun. Generally speaking, anyone who could recognize the Pole Star and the Great Bear was doing rather well.

Television at that time was decidedly primitive as well. Of course it was all black and white, and because recordings were not up to standard everything had to be ‘live’, so that disasters were not uncommon. There was little in the way of electronics, and producers were compelled to use all sorts of dodges, as I was to learn very soon in my BBC life.

One initial problem we faced was the selection of opening music, which is actually more important than might be thought. The usual suggestions, such as ‘You Are My Lucky Star’, were rejected out of hand. We also dismissed Holst’s Planets, partly because it was too obvious but mainly because it was astrological anyway. Finally we hit upon a movement from Sibelius’s suite Pelléas et Mélisande. It was called ‘At the Castle Gate’, and it proved to be a great success. We still use it, and have not thought of changing it. Only once did we vary; for our last programme about Halley’s Comet, in 1986, the Band of the Royal Transport Corps played us out with my own march, appropriately called Halley’s Comet.

In pursuit of ‘props’, we went to see Alfred Wurmser, a charming Viennese who lived in Goldhawk Road. He had a dog named Till, half-Alsation and half-Wolf, who weighed about a ton but was under the strange delusion that he was a lap-dog. Alfred made moving diagrams out of cardboard, and he soon became enthusiastic, so that we continued to use the ‘wurmsers’ until he decided to return to his native Austria. The original title of our programme was to be Star Map, but we changed it to The Sky at Night almost at once – to make sure that the new title went into the Radio Times.

At that stage we had a stroke of luck. A bright comet appeared, and caused a great deal of popular interest. Could it be an omen?

Comets have often been classed as unlucky, and held responsible for dire events such as plagues, earthquakes and even the end of the world. We know better. A comet is a ghostly thing, and has been described as a dirty iceball, so that it could not possibly knock the Earth out of its orbit; one might as well try to divert a charging hippopotamus by throwing a baked bean at it. The new comet, Arend-Roland (named after the two Belgian astronomers who had discovered it) was unusual inasmuch as it appeared to have two tails, one pointing away from the Sun and the other toward it. Actually the sunward ‘tail’ was due to nothing more than fine dust spread along the comet’s path, but it looked intriguing, and for several evenings during April the comet was easily visible with the naked eye.

Obviously, Arend-Roland had to be the centrepiece of our first programme. I took photographs of it, and managed to obtain others; we revised our original plans, even relegating an eclipse of the Moon to the last few minutes of the programme. Eventually we were ready for transmission – or so we hoped. Remember, I had been on television only once before, and I had no real idea of what to expect, particularly as I had no guest appearing on the programme with me.

Rehearsals seemed to go well. Even at that stage I had no word-for-word script; Paul trusted me to bring in the visuals (photographs, diagrams and ‘wurmsers’) at the right moments, and otherwise it was up to me. And so at 10.30 p.m. on the evening of 26 April 1957 I was seated in my chair in the Lime Grove studio waiting for the red light over the television camera to come on.

Was I nervous? In a way I suppose I was; I remember thinking ‘My entire life depends upon what I do during the next fifteen minutes.’ Then the screen on the monitor began to glow; I saw the words ‘The Sky at Night. A regular monthly programme presented by Patrick Moore’, and the series was launched. It did not then occur to me that I would still be broadcasting almost fifty years later.

I waited anxiously for reactions to that first programme. I was grateful to that twin-tailed comet, and I was very sorry to see it depart from our skies a few weeks alter. It will never return – it had the misfortune to pass by the giant planet Jupiter, and was unceremoniously hurled out of the Solar System altogether, so that even if The Sky at Night is still being broadcast a few tens of thousands of years hence, my successor will be unable to welcome Arend-Roland back. Meanwhile, we all wanted to know whether we had made the programme (a) too elementary, or (b) not elementary enough, or (c) pitched at about the right level.

This is always a problem, and I can only hope that we have guessed right. It is true that the programmes today are watched by many professional astronomers as well as amateurs, no doubt because the field has become so vast that nobody can hope to cover it all: for instance, a student of remote galaxies need not necessarily know much about the polar caps of Mars. We also have to cater for viewers comfortable in their armchairs watching the programme because they have not mustered up enough energy to get up and switch off. Our aim is to capture their interest as well.

Within a day or two of our first foray, letters began to flood in, and most of them were encouraging. I answered them all; as with rare exceptions I still do; the Woodstock works until it is almost red-hot. Mind you, there are occasions when I have been baffled. One early correspondent wrote to me saying that he had enjoyed hearing me talk about comets; and in consequence now wanted to buy an Army tank: had I got any? There was also the dear lady who was anxious to communicate with the beings who live on the Moon, and wondered whether it would be possible to send a carrier pigeon there. I suggested sending a pigrot – i.e. a bird which was a cross between a pigeon and a parrot, very useful, as it could convey verbal messages.

Flying saucers will not go away, and I remember one episode in July 1963 when a peculiar crater appeared in a potato field at Charlton – not the London Charlton, but a small village near Shaftesbury, in Dorset. A local farmer made the discovery, and also saw that the crops over a wide area around had been flattened. Reports over the radio and in the press caused widespread interest, and this was heightened by a statement from an Australian who gave his name as Robert J. Randall, from the rocket proving ground at Woomera. Dr Randall maintained that the crater has been produced by the blast-off of a saucer from the planet Uranus. It was independently suggested that there might be a bomb in the crater, and an Army disposal squad was called in.

When the whole affair started to look really interesting, I happened to be in a television studio. We decided that whatever was happening, we ought to be ‘in’ on it, so at the dead of night we drove to Charlton, arriving in the early hours to find all sorts of people hopping about like agitated sparrows. The bomb disposal squad was at work, but had unearthed nothing except a small piece of metal which might have been anything. As I knew something about dismantling bombs, I was called in, and I had no qualms, if only because I thought that the chances of there being any buried explosives there were about a million to one against. There was also a water diviner, marching around with an impressive assortment of twigs; there were several astrologers, at least one telepath, and various local Saucerers. The teeming populace was kept away by improvised fences, though I was allowed to go where I liked. The crater was evident enough. It looked as though it had been caused by subsidence, but more than that I could not really say.

We then tried to locate Dr Randall, but could find only a relative of his who seemed to be the local district nurse. Strangely, Woomera disclaimed all knowledge of anyone of that name; we went so far as to telephone Australia. So far as I know, nobody has seen him since, though some time later he did issue a report on the Charlton affair, adding that on another occasion he had come across a grounded Uranian saucer and had had a long conversation with the pilot, who rejoiced in the name of Ce-fn-x.

I did track down the rumour that when the spacecraft landed, it killed a cow. What had happened was that during a discussion at a local pub a farmer had said ‘Ah! and, you know, a cow of mine died last week, too!’ with the inevitable result that a journalist overheard, and another sensational headline was dispatched to a newspaper.

I drove past Charlton a few weeks later, but all was quiet, and there have been no further cosmic visitations. By then the main interest had switched to Warminster, a pleasant little Wiltshire town. Various sightings had been reported from there, mainly from the adjacent Cradle Hill, and eventually I went to Warminster with a television team, arriving soon after nightfall. It proved to be a fascinating experience, but Saucers failed to put in an appearance.

Only once have I been really thrown. This was in 1977, when I was carrying out some observations of the Moon with my 15-inch telescope. Suddenly a whole crowd of Saucers came toward me. They moved slowly but deliberately; in the telescope field, they glowed with a strange, eerie light, and they were genuinely Saucer-shaped. As I watched, mesmerised, they sheered off and vanished. I simply did not know what they were, and only in the following day did I find the answer: pollen, catching the rays of moonlight and being seen totally out of focus.

The Saucer craze has waned now, even though a few years ago the European Parliament seriously considered setting up a helicopter base to accommodate visiting aliens (an idea absolutely typical of our would-be masters in Brussels). No doubt the new landings will be reported at some time in the future.

I was once asked what I would say if a Saucer landed on my front lawn, and a little green man emerged. I replied that I knew exactly what I would say. ‘Good afternoon. Tea or coffee? Then do please come with me to the nearest television studio.’ There is nothing I would like better than to interview a Martian, a Venusian or even a Saturnian, but somehow I don’t think that it is likely to happen.