13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

The detective is a familiar figure in British history. This work looks at famous cases such as the Ripper murders and the beginnings of the Special Branch and Detective Branch of Scotland Yard. This history covers various aspects of crime history, including the career of Jim 'the Penman' Saward, a notorious forger, and more.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2007

Ähnliche

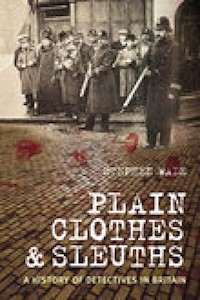

PLAIN CLOTHES & SLEUTHS

A HISTORY OF DETECTIVES IN BRITAIN

PLAIN CLOTHES & SLEUTHS

A HISTORY OF DETECTIVES IN BRITAIN

STEPHEN WADE

First published 2007

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port Stroud,

Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Stephen Wade, 2007, 2013

The right of Stephen Wade to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUBISBN 978 0 7524 9649 8

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

Introduction

Acknowledgements

1

Before Scotland Yard: Amateurs and Learners

2

Peel, Mayne and Rowan

3

The First Decades: The Social History of the New Detectives

4

The First Decades: The Men and Their Cases

5

The Trial of the Detectives: 1877

6

Hunting Jack the Ripper and Charlie Peace

7

Special Branch: Section D – 1888

8

The New Sleuths: Professionals and Amateurs

9

Major Cases c.1900-40

10

The Making of Yard Men

11

In and Out of the Smoke

12

Case Studies in Charisma

Conclusions

Bibliography

INTRODUCTION

In August 2006, a story in The Times revealed that a cold case murder of 1967 had been solved: two men were being held and had been charged with the killing of Keith Lyon, a boy who was stabbed eleven times in the chest and back as he walked on the Sussex Downs. Why had this taken so long to solve, and for closure to come, sadly after the deaths of the boy’s parents? As The Times explained: ‘The lost evidence was discovered in 2002 when a group of workmen upgrading a sprinkler system’ found a box containing vital evidence. This box had been misplaced in 1967.

This is exactly the type of story that has always created a doggedly persistent ambiguity in the public’s view of the police detective: on the one hand a Holmes-like genius of observation and deduction and on the other a bungler who makes basic mistakes that cost lives and reputations. It was always the same, since the creation of the detective force in 1842, and even before then when the Bow Street Runners and Patrol tried their hands at detective work.

The police detective has also had to suffer the eclipse of his actual work and nature by the literary detective, a creation of mythic status. In 1960, Christopher Pilling wrote that Chesterton’s Father Brown had a point when he said that ‘Ours is the only trade in which the professional is always supposed to be wrong.’ Pilling added, ‘Intuition may be a long way off legal proof: sometimes now we are taken right through the trial, instead of finishing with the arrest in detective fiction, when the detective can say he has lost interest and go back to his violin … ’

This book seeks to counteract these social mediations, recounting the creation of the first detective force in Sir Robert Peel’s new police, and taking in some account of how the actual professionals measured against Dickens’s inventions and of course, Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes. It was a long and arduous struggle to shape a detective branch: in their first phase they were highly suspicious, as any whiff of plain clothes activity suggested the kind of nasty business undertaken by agents provocateurs in the dark days of Chartism and working class radicalism. Men in plain clothes had infiltrated the ranks of desperate mill-workers who had bought firearms in the suburbs of the industrial cities of the north, and they met in pubs and inns to hatch their plots of subversion. Among them had been officers of the government, drinking and joking, while all the time noting names and places, dates and intentions.

Peel, in his Police Act of 1829, was not starting from a complete void – there had been professional administrators who had made some moves towards a streamlined metropolitan police well before Peel’s time as Home Secretary. In the middle years of the eighteenth century, the novelist Henry Fielding and his blind brother John, along with other various military men, had made some notable steps forward in this context. But the change from a small force patrolling London at night and night watchmen in their booths, to armed and disciplined officers organised in a military fashion, was an immense leap forward. One handbill of 1830 raises most of the issues emerging at the time through fear and distortion:

Ask yourselves the following question:Why is an Englishman, if he complains of an outrage or an insult, referred for redress to a Commissioner of Police? Why are the proceedings of this new POLICE COURT unpublished and unknown? And by what law of the land is it recognised?

The aims of this social history are manifold. I want to look again at the men involved in this steady evolution of detective science and to ask questions about how they learned their trade and how the systems needed to protect them eventually evolved. Police work on a beat system is perilous in the extreme, and many police murders in the first decade of the new force show this vulnerability. My discussion of the P.C. Clark case (1846) in Chapter 4 highlights this world of danger they lived in day-to-day. But the real fascination is what Dickens understood, as he expressed in his piece, ‘A Detective Police Party’, from Household Words in 1850:

From these topics, we glide into a review of the most celebrated and horrible of the great crimes that have been committed within the last fifteen or twenty years. The men engaged in the discovery of almost all of them, and in pursuit or apprehension of the murderers, are here, down to the very last instance.

In other words, Dickens saw the magnetic fascination of the public with such men. The sensational murders of the first decades of the detective force – both in London and in the provinces – were major media narratives, and yet the men who pursued the villains were not well known. The detective does not want to be a celebrated person. He wants to enjoy the advantages of being anonymous, of course. But many of the men Dickens met and wrote about were also former military men and so very much accustomed to doing their duty and not crowing about it.

In an age when the penny dreadful magazines and street publications made murder narratives immensely popular (and lucrative for the publishers and vendors) the new interest of a professional force of men in pursuit was a high profile element in the genre. Formerly, the stories, as in the very popular Newgate Calendar for instance, focused on the villains and their adventures, from crime to scaffold in many cases. These stories, first issued in 1773, were republished in the 1820s. They told the rip-roaring adventures of such highwaymen and robbers as Dick Turpin and Jack Shepherd. Now, writers and publishers had a whole new dimension of crime narrative to exploit. The detective was at the core of this new media production.

Much of the following account of the birth and growth of the detective in England is necessarily concerned with a process of learning, and this has different planes of interest. First there is the everyday strategy for coping with crime on a grand scale. This meant a gradual development of arms, teamwork and logistics. Then there is the ongoing struggle for the individual of talent working within a system, an organisation. At first the organisation was like a regiment – men were sacked regularly for the same misdemeanours for which they would have been flogged or court-martialled in the armed forces. Later, individuals could specialise, as forensic science progressed. Certain advances were stunningly revolutionary for the profession, notably fingerprinting at the end of the nineteenth century and of course, in my circumscribed period, the special elements such as the Flying Squad and the Fraud Squad.

Ironically, when the police force was being formed in England, the founding father of crime detection, Eugene Vidocq, was in England. He did visit the prisons of Pentonville, Newgate and Millbank, but he was really in London to organise an exhibition. He wanted to be a showman, not a professional adviser. As James Morton has commented in his biography of Vidocq: ‘Not only was he on the premises during opening hours but he also put on a little production in which he appeared in various disguises, to the delight of the audience … ’ He had arrived in London three years after the detective force was formed, and had played no part in the detective policies; he had, however, been in London in 1835 to advise on prison discipline. He was a man who had known the worst prisons in France, as a prisoner as well as in his role as police officer. In 1845 he was thinking of starting up a detective agency, extending the one he had in France, but this was clearly not his real motive for being there.

Finally, there is the question of the whole range of other contexts in which the detective has moved, as his need for greater knowledge has increased. However fantastic and far-fetched we find Sherlock Holmes to be, Conan Doyle did understand the need to have knowledge of esoteric areas of life inherent in detective work. The basic skills of filing, classifying, noting observations and memorising faces and biographies is there in Holmes. The first detectives appear to have kept an immense amount of local information in their heads as they walked the streets, cultivating contacts and ‘grasses’.

This process of absorbing a body of knowledge involved amateur science in all kinds of affairs. A detective in the Victorian period had to constantly add to his geographical and trade knowledge. He also had to be familiar with a complex street slang and code of behaviour.

In the twentieth century, after the revision of the detective training curriculum in the 1930s, we have the emergence of the ‘star’ sleuths. These were the men the newspapers loved. Popular film and fiction had made figures such as Fabian of the Yard and Sexton Blake the epitome of the flash, showy, intelligent gentleman, an officer type who was part Holmes but part slick modern man, an habitué of parties, hotels and high-level meetings with ‘top brass’. Of course, there was capital punishment until 1964, and so these new detectives with impressive credentials and equally notable cars were called on to travel into the regions and help the local bobbies. This gave the newspapers yet more fodder for their sensationalism and love of personal trivia when they made a professional into a media star.

The overall course of the evolution of the detective in England has been one of steady acquisition of a range of professional skills, but at the heart of this dangerous, challenging and unhealthy profession is an armoury of abilities that defy definition, ranging from instinct to incisive logic. The ‘nose’ of the true sleuth was learned by bumbling – naïve trial and error. The streets and their turbulent, complex network of crime and criminals taught the detective how the business of crime works. In one of the early cases of the murder of a policeman – the second murdered officer after the 1829 Act – P.C. Long was knifed in Charing Cross Road and a man arrested and eventually hanged on the slenderest of details, mainly that he wore a brown coat and a witness had said the killer wore a brown coat. Place that by the side of the incredibly complex investigations of a late twentieth-century murder case, when the trappings of science and professional procedure dominate every step of the police work, and the historical process is perceived clearly.

When Leonard ‘Nipper‘ Read, the man who caught the Krays, was finally induced to write his memoirs (with the help of James Morton) he paid tribute to the man who had taught him the detective’s trade, Martin Walsh. What Read had to say about Walsh is arguably the clearest definition of standard and successful detective work ever expressed. Read said:

He was, without doubt, the most dedicated man I have ever met. Everyone knew his qualities. He was tenacious and persistent. The words could almost have been coined to describe him. He would sit, and have me sit with him, for hours on end observing a suspect. He would watch someone leave a building and say ‘he’ll be back.’ When after a few hours I would say, as an impatient 22-year-old, that we had blown it, he would reply, ‘Give it a bit longer.’ … Sure enough, the man would return.

The detective needs some kind of challenge and competition to keep improving and to put up with the waiting and the boredom of the job. Martin Walsh had made that tedious element of the work his motivation and his professionalism. In the first two decades of the new detective police, the most likely reason why skills were sharpened and expertise developed was the fact that the Bow Street Patrol that the detectives in Bow Street commanded were still there, some alongside the new officers, as rivals.

One of the main barriers to progress at first was the social and political context. Peel had conceived the notion of a professional police force not only because it was long overdue, but also because that particular time, the late 1820s and early 1830s, was a perilous time to be alive. It was a time when the first real impact of mass immigration, extreme urban poverty, the crisis of radicalism and the challenges to the criminal justice system were all having a massive presence in both the metropolis and in the provinces. Riot and disorder had been common features across the land for the last eighty years and more were to follow in the 1830s. The previous system of runners and ‘Charlies’ (watchmen) had clearly been inefficient and prone to corruption.

Crime and the threat to social stability was noticeable everywhere. After all, in 1812 a British Prime Minister, Spencer Perceval, had been assassinated. In 1819 the massacre of Peterloo in Manchester had shown the ordinary people that the establishment was happy to set the army on them if they gathered for a meeting. London itself had ‘no-go areas’ in the rookeries where criminals could escape pursuit.

Detection was to come much later, long after the ruling mindset of prevention began to be seen as a failure. The law and its personnel in all areas had to learn that if detection could be established, however clumsily and slowly, then there might be a different kind of deterrent – something totally unlike the threat of beatings, imprisonment or transportation. As ‘Plain clothes’ was a detestable concept it also took a long time for something else to be recognised – the possibility that a police officer might be capable of understanding the villains by learning their cultural basis and their sense of social identity. The ‘criminal tribe’ was no longer to be a separate, inscrutable sub-group in its own circumscribed ‘patches’.

This has been a quest for truth beneath the thick layering of myth and metaphor that has hidden the reality of this aspect of police history for so long. Beneath the literary and filmic imagery though, there has always been a desire on the part of artists and writers to reveal the untold story of the inner lives of detectives – the stuff of fiction that occasionally shows through the fabric of the course of social history.

My thanks go to the writers who previously applied their research and narrative expertise to this subject, notably Belton Cobb, Martin Fido, Keith Skinner and Douglas Browne. Staff at the London Metropolitan Archives have been very helpful and also my fellow crime writers Lesley Horton and John Styles.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Permission to use four pictures from the Metropolitan Police collection is accredited.

My thanks go to Eleanor Fletcher and Maggie Bird at the Resources Directorate.

1

BEFORE SCOTLAND YARD: AMATEURS AND LEARNERS

For centuries, ever since the first justices of the peace were established in the medieval period, the notion of acting against criminals was focused on the magistrate himself (at first voluntary) and the ‘Reeve’, later called the shire reeve and eventually ‘Sheriff’. The system of criminal law before the mid-eighteenth century was largely concerned with accusers gathering and placing a recognizance before a local magistrate. He would then take action, but there were no officers to investigate.

In the tiny village of Long Riston, near Beverley, in 1799, a group of local people took out a recognizance against three people who they alleged had brutalised and eventually killed a little boy, the son of two of the accused. It was a case of murder. The adults clearly had the intention of beating and whipping the child until they had taken away his life. No one went out to start a process of enquiry and detection; they merely came to the East Riding of Yorkshire assizes to stand trial. Whatever investigation and evidence was collated there would be placed before the jury.

In that case, the assize records show something intriguing and fascinating. It is an occurrence that explains much of the local power and social interaction in criminal cases before the regional police forces slowly emerged after the Municipal Corporations Act of 1835. At the bottom of the assize record, written in pencil, are the words ‘guilty’ written next to all three accused. But then a line has been put through the name of the man. ‘Not guilty’ was written in its place. It would be a positive thought to assume that some kind of investigation had taken place, but more likely we are talking about a local power structure: he may have had debts and transportation would have meant that these debts would never have been recovered. He may simply have had powerful friends. Or there may have been evidence to exonerate him.

British criminal history before the 1829 act, with the exception of those parts of London around Bow Street, was subject to a dominance of the idea of prevention, not detection. Cases of investigation and police work are rare in the regions, while Henry Fielding and others, as we shall see, were beginning to establish detective work. There are rare examples, however, and one case study from West Yorkshire shows that at times magistrates of special ability did turn detective. Such a man was Samuel Lister, of Little Horton, Bradford. Lister was living and working in the heartland of coiner country. Clipping the King’s coinage was a very lucrative business at that time (the mid- to late-eighteenth century). Lister was a Justice of the Peace between 1751 and 1769, and he achieved a remarkable feat of detection – he tracked down a forger to the source of his work and his base in Gloucestershire.

Coining then was a capital offence. The Calderdale coiners had made a remote fastness in the hills to where they could retreat into farms well away from the new towns. But Lister, along with his magistrate colleagues at the time, was expected to take on a large workload and there was a shortage of talented magistrates. By the last seven years of his period of office, a great deal of the legal business of the western half of the textile areas around Bradford came under his responsibility. One of his many duties, but one not at all well defined, was to bring felons to justice. Most magistrates had no time for this, but Lister went in pursuit of some, and his most outstanding case was that of his detection of man who called himself Wilkins, apprehended for not paying his inn bill. In January 1756 Wilkins was standing in the dock before Lister. The man had some highly unusual documentation on him, including a letter from Lord Chedworth, giving him immunity from arrest in a civil court. He also had a promissory note for the huge sum of £1,100. Lister was intrigued.

It seemed that Wilkins had forged notes and bills, not actually clipped coinage, but this was a capital offence. Lister did an amazing thing – he circulated details of the man, notably into the area of Painswick, Gloucester. He placed information in the London press also; the man was actually Edward Wilson, a clothier from Painswick. He had been forging bills in the West Country and was a wanted man. He was convicted and received a death sentence.

The kind of activity Lister engaged in was impossible for magistrates as a general rule; he was an outstanding man with a passion for detective work. What he did was almost a twentieth-century piece of police work, communicating across the counties to ascertain a true identity of a suspect. His suspect could have been released at any point on bail by a friend. There was therefore high drama: a chase for information before the system stopped both the arrest and the trial from taking place.

The general system of policing before Peel though, was one in which the key figures of magistrate, parish watch and other local dignitaries and landowners made up the general scene. In London, before Peel’s act, we need to trace the beginnings of any smack of professionalism to the Fielding brothers: Henry the novelist, author of Tom Jones, and his blind brother John. Particularly after the beginnings of the gin craze, after its introduction into Britain in 1735, crime escalated in London and other towns. Assaults and robberies related to drunkenness, poverty, insanity and sheer desperation were subject to the brutal repression of the ‘Bloody Code’ – a long list of capital crimes on the statute books making such offences as stealing a sheep or even robbing a bit of cloth into a hanging matter.

In Fielding’s London, the idea was that there would be a shift-work process, in which the good people of the city would take turns as constables. Of course, as they were unpaid and it was dangerous work, this did not happen. The small number of paid officers extended only to the ‘Runners’. These existed in places other than Bow Street, but that location has claimed the name. At Bow Street the magistrates looked after the Runners and also the patrols. These were a small force of road patrol officers who policed the outskirts of the city. In central London the ‘Charlies’ were supposed to watch the streets in some areas, but they were subject to corruption and were not exactly fit men.

Dickens, writing in 1850, had another viewpoint on the Runners:

We are not by any means devout believers in the old Bow Street Police. To say the truth, we think there was a vast amount of humbug about these worthies. Apart from many of them being men of a very indifferent character, and far too much in the habit of consorting with thieves … they never lost a public occasion of jobbing and trading in mystery and making the most of themselves …

Henry Fielding has to take the credit for the ‘thief takers’ however; he added this small select group of men to the Bow Street staff after he became Chief Magistrate at Bow Street in 1748. John Fielding, following him in 1754, was really responsible for the larger force that became the Bow Street Runners. Like Lister, however, Henry Fielding saw the importance of communication. He started the Covent Garden Journal in 1752. This only lasted for a year, but it was far-sighted and was a beginning in this important branch of detective work. A report in the issue for 10 March 1752, for instance, is the first instance of the manoeuvre of ‘putting a person up for identification’. With details such as ‘Saturday night last one Sarah Matthews, a woman of near fourscore brought a woman of about twenty-four before Mr Fielding’ and ‘It appeared that her former marriage was a falsehood and that the old lady was the lawful wife … ’

Of course, when there were severe riots, this force could not cope. When there were major problems of social disorder, the army were called out; the militias were accustomed to a tough repression in these cases. A common solution to the problems of disorder was simply to intensify the military actions, treating rioters as an enemy army. By the end of the eighteenth century, when the country was quite used to large bodies of military and naval men around the land, the militia regiments were often keen to practise using swords and guns against the ‘rabble’.

But something large scale and more humane was needed. The time was right for a person with outstanding qualities of organisation and problem solving to appear. A man who had been Lord Provost of Glasgow, Patrick Colquhoun, was that man. After moving south to London in 1789, he became a magistrate. He was only thirty-seven but eager to achieve something substantial in this context. His concept was that it was high time that something more than mere prevention of crime was needed. His book A Treatise on the Police of the Metropolis, published in 1796, went through seven editions in ten years. Colquhoun was many things, including the father of the soup kitchen, a result of his profound concern for the plight of the poor. He was one of those philanthropists who were also known at the time as commercial diplomats – a product of the Enlightenment who noticed the underclass and cared about them.

Colquhoun had the vision to see that what was needed was a number of police commissioners, men with salaries and defined responsibilities. He even suggested a place in the proposed new order for the watchmen, advocating them as a reserve force as the militia is to the regular army. The platform for opposition to his ideas would come from the rates, the ongoing problem of why the British ratepayers would want to finance men in a ‘police state’ in which the notion of law would be revolutionised and the ordinary man deprived of personal liberties. Colquhoun saw that some duties secondary to actual crime prevention could be included in the remit of the hypothetical police force. Obviously, Robert Peel was aware of these ideas and they were undoubtedly an influence on his thinking a few decades later.

He also conceived of a series of districts with departmental officers, something that would happen in 1829. But he was more than a crime theorist. Colquhoun was also a statistician and a typically enthusiastic social scientist of his age, gathering facts and figures, listing businesses and traders in various categories. All this would play a part in his thinking as he devised what we would now call the application of logistics to the municipal corporations’ functioning. As he wrote, the cost of policing would, ‘go very far towards easing the resources of the County of the expenses of what the Select Committee of the House of Commons denominate a very inefficient system of police.’

Pitt, in 1798, forwarded these ideas to Parliament but there was a massive and widespread protest. When a bill developed from these proposals was about to be discussed in the chamber, Pitt stood down. The consequences of this led to the bill being dropped. But there was one aspect that survived and was applied, and it was a very important one – the policing of the docks. As the new police were to discover in the 1830s, trying to tackle the problems of smuggling and theft along the Thames was a gargantuan problem and it was open to corruptive practises. At times, constables in Peel’s force were to be subject to the temptation of co-operation with the villains, such were the financial rewards available. Colquhoun wrote about the ‘plundering’ of the docklands. He saw the weaknesses in the process of revenue investigation and excise, and he proposed a river police. By 26 June 1798, it was announced that a river police to be called the Marine Police Institution was to be formed immediately, with its base at Wapping. It was a force of considerable presence, having eighty officers in its original staff. This came about because of a Captain Harriott, who was a magistrate as well as a navy man. Then in 1800, a bill was passed (with the help of Jeremy Bentham) to provide the Thames Police Office with three stipendiary magistrates. Harriott himself took control of this for six years.