Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

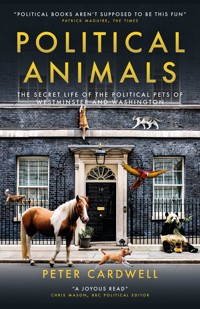

Larry the cat, chief mouser of Downing Street, has seen off five Prime Ministers so far and is a national treasure. Though certainly the most famous cat in Britain, Larry is only one of a long line of political animals at the seats of government on both sides of the Atlantic. From pandas and platypuses to Labradors and lions, animals have long shored up peace between rivals, clinched election campaigns, caused divisions within parties and left their unique calling cards in the halls of power. Journalist and former special adviser Peter Cardwell traces the political (and not-so-political) adventures of these fascinating pets from Tudor times to No. 10's newest kitten. Drawing on exclusive interviews with Washington and Westminster insiders, including Prime Ministers past and present, Cardwell reveals never-before-heard tales of political pets and offers a fresh insight into the enduring relationships between those in government and their furry friends.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 357

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iii

v

To my boy Jack – the best cat I could ever wish for And in memory of Clyde, who left her paw print on my heart

vi

Contents

Preface

Political life on both sides of the Atlantic has been many things in recent years, but it has seldom been boring. There are few constants; instead, there is a seemingly ever-changing cast of politicians and a revolving door of political debates, referendums, elections and parties. It’s been hectic, stressful and often brutal for both those involved and those watching – as I know from personal experience.

But alongside the busyness, there is calm. I’ve had two jobs in my career: being a special adviser to the UK government, and reporting on it. What no one tells you about politics is that there is an awful lot of hanging about, waiting for things to happen. The Prime Minister has his or her schedule timed to the minute, organised by a small army of people whose job it is to move them from engagement to engagement, maximise every moment and make sure they meet the correct people and there are no exit signs above their head in photographs. But almost everyone else has to wait around for these events to occur to take part in them.

Journalists reporting live from Downing Street may seem in the thick of the action, but the five minutes for which we are on air are often accompanied by fifty-five minutes of that hour waiting for the next ‘hit’. There is only so much phoning of sources, checking in with the news desk, reading of Twitter and listening to the cameraman whinge about his break that can be done. xPolitical life, despite its pace, has many moments of pause. And, as I realised, it also has a lot of paws.

It was on one such slow day back in 2016 I was waiting to broadcast live when I first met Larry the cat. Palmerston, the Foreign Office feline, also came over to say hello. I’ve always been a huge cat person, so I asked a colleague to take some photos, which I then posted on Twitter.

I quickly realised the snaps of the moggies (and, to a lesser extent, me) had much more of an impact than many of my reports about the humans in Downing Street. ‘Look!’ people seem to say, ‘There are cats! Yes, there’s Peter, but mainly there are cats!’ It was clearly a rich seam of reporting, so any time I was outside No. 10, I gave a little update on the cats via social media. Many other reporters have done the same, not least Justin Ng, a photojournalist who has become big pals with Larry over the years and never has a packet of treats (specifically Dreamies) far from his reach.

A few days after Sir Keir Starmer was elected Prime Minister in July 2024, I exclusively revealed on Twitter that Jojo, his family’s rescue cat, had moved from their home in north London into the flat in Downing Street. I have seldom received such a response: over 1.6 million views and comments from around the world. It brought home that people want to know about politics, yes, but they also want to know about political animals. They’re high-profile and much-photographed, but there is always a curiosity about what they may think about their humans and the other politicians who visit their patch. It was once said to me that animals do speak, but only to those humans who know how to listen. I challenge anyone to look at the photograph of xiHumphrey the cat and Cherie Blair in the photo section and tell me Humphrey didn’t know the score about the controversy around his removal from Downing Street in 1997!

And as someone who loves cats even more than I do politics – for context, my idea of fun as a fifteen-year-old was reading Sir John Major’s autobiography – I knew it was time to apply my God-given nerdery to my life’s two greatest passions: animals and politics. This book is the result. I know Washington well, having been first an intern at various TV networks and then a professional journalist with the BBC there. I know Westminster even better having been a producer and reporter for a number of stations, most recently as political editor and now presenter on the Talk network. At Talk, we even ran a feature called ‘Cat of the Week’ on my Saturday shows for 100 editions, in which viewers submitted photographs and videos of their favourite felines. Two of the cats in this book, Evie and Ossie, featured at one stage, as well as the Conservative MP Tom Tugendhat’s cat, leading to me referring to him on air as ‘Tom Tugendcat’. We eventually extended the remit of the slot and ‘Rescue Animal of the Week’ was added on Sundays after the inevitable backlash from dog people.

PoliticalAnimalsis mainly about cats and dogs; however, some arachnophobic readers may wish to skip the short chapter on Cronus the tarantula. Another species features prominently – the main reason for all the cats: the mice! Yes, the kitties are cute, but they arealso meant to have a job (take note, lazy Larry).

I worked as a special adviser (SpAd) to four Cabinet ministers for three and a half years (2016–20) across four different departments. My time in politics was a busy one, with many reshuffles and a churn of ministers and even Prime Ministers. I wrote a xiibook about it, TheSecretLifeofSpecialAdvisers, published by Biteback. In 2019, I had the pleasure of working with Lucy Frazer KC, who was Prisons Minister in the Ministry of Justice. In all my time working with her, I never saw Lucy rattled. Quite the opposite: I found her diligent, focused and good fun. But there was one issue where Lucy’s coping skills deserted her.

Her parliamentary researcher, Timothy Stafford, knew in 2019 that his years of political training, a hard-won degree from Oxford University and his graft and guile in climbing the greasy pole to work for such a high-ranking politician had not been wasted. At around 6 p.m. one evening, Stafford was about to head home when he received a call from his boss summoning him to her main office. ‘Timothy,’ Frazer reported breathlessly, ‘there is a mouse by my handbag, and I need you to be brave!’ Stafford rushed to defend his boss, but between them they never found the mouse nor, despite their best efforts, did they get rid of the wider problem of its compatriots in the office. Westminster is full of similar tales.

On numerous occasions, I have been sitting in the House of Commons riverside canteen enjoying their delicious fare and seen mice scurrying along in search of some morsel dropped on the floor. I have, thankfully, never seen a rat, but numerous friends and colleagues have reported those too. The same goes for government offices in Whitehall, where civil servants have been known to sit with their feet slightly off the ground to avoid any encounter with mice.

And it was that desire – both contemporary and historical – to get rid of the rodents that so blight Parliament which has prompted so many politicians to acquire animals, mainly cats. xiiiThat said, some politicians, of course, like many people around the world, just love animals and want a dog or cat for their family to care for and to make part of their home.

One of them was Sir Robert Buckland, my boss at the Ministry of Justice when he was Lord Chancellor and Justice Secretary. A few months after I’d left his employment – Boris Johnson’s chief enforcer Dominic Cummings had sacked me by that stage – Robert’s wife, Sian, lamented the fact that she had a problem getting a cat he would be happy with. Their previous cat, Megan, was a rescue from the welfare charity, Cats Protection. They had tried the local shelters again for the female, grey cat Robert wanted but had had no luck.

‘Leave it to me,’ I said.

Putting my ‘Buckland fixer’ hat on once more, I spoke to the Advocacy and Government Relations team at Cats Protection, the part of the charity that campaigns for animal protection legislation. As a lifelong advocate of not buying animals from breeders, I was determined the Bucklands would find a rescue cat. I asked the Cats Protection team if they would like a nice picture of a Cabinet minister and some warm words in a press release (which I would end up mostly authoring) about the charity and the importance of adopting animals. Funnily enough, they welcomed this valuable free publicity.

And thus Tiny, aka Mrs Landingham (after President Bartlet’s secretary in the TV series TheWestWing), became part of the Buckland household in Swindon, where she has thrived and been loved by the family ever since. Job done.

One of the most vilified figures in recent British political history is the aforementioned Dominic Cummings, known best for xivtwo things: being Svengali to Boris Johnson and testing his eyes by driving to Barnard Castle during the first Covid lockdown. I always got on with Dominic fine and even after he sacked me, we had a good old chinwag about his historical project on Otto von Bismarck at a wedding. But there is no doubt that Cummings is a hated figure with Bond villian-esque qualities for some. Yet even he is an animal lover.

In a 2025 Spectatorarticle, Cummings’s wife Mary Wakefield wrote of their new kitten, George:

Dom is a kind man, but his feelings about the politicians he often works with are not kind. In the pre-George era, his usual monologue, reading the political news of the day, went like this: ‘Gah! B******s. Clowns. Idiots.’ Just twenty-four hours after George arrived, it took a new turn: ‘Gah! B******s. Clowns. Idiots… Oh, hello kitten! What a lovely kitten! What a brave and perfect kitten!’

The cat even made a brief appearance in a Sky News podcast on which Cummings was a guest in May 2025.

Even the Prince of Darkness himself, Peter (now Lord) Mandelson, has always been a dog person. In 2000, the writer Donald Macintyre described how Mandelson, then Northern Ireland Secretary, was speaking to Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams at Hillsborough Castle when Mandelson’s dog, Bobby, came up to the pair with a rubber bullet in his teeth. ‘It’s my contribution to decommissioning,’ Mandelson is reported to have said.

A photograph that sits proudly on display in his official residence is of his late dog Bobby breaking royal protocol by licking xvthe late Queen’s hand. And, more recently, as UK ambassador to the United States, Mandelson was accompanied to Washington by his border collie, Jock.

This book has quite a lot of history in it, but I suspect the current and recent cats and dogs of Westminster and Washington are going to be of most interest to readers. What this book does not really cover is the politics of the last few years, and why should it? There are many books written by much better authors on the internal machinations, the changes and battles of politics. I’ll leave it to the experts to tell you what really occurred in the rooms where it happened; I’m going to tell you about some players who observe major events, never leak stories and can humanise even the most loathed figures in Washington and Westminster.

There are so many intriguing, fun and outrageous stories about animals in politics. My plan is to take you by the hand – or even the paw – and lead you behind the black door of Downing Street and inside the White House to hear from key people, some of whom have never given interviews before, about the wonderful world of our furry friends, the political animals of Westminster and Washington.

Peter Cardwell

London

July 2025

#AdoptDontShop xvi

PART I

A HISTORY OF POLITICAL ANIMALS2

Chapter One

A History of British Political Animals

In Ancient Egypt, cats were worshipped as gods. The Chinese looked to dogs for guidance in antiquity. The reign of Roman Emperor Caligula, who ruled from ad 37 to ad 41, can be described as eccentric at best and at worst, unhinged and cruel. Animals played a part in his mercurial leadership. He once threatened to make his horse, Incitatus, a consul – one of the highest Roman political offices. Some historians see this as a sign of Caligula’s madness; others view it as a rebuke to the senators of Rome in implying that a horse could do a better job than they.

In England, cats have quite literally been at the seat of power since the time of Cardinal Wolsey. Wolsey was Lord Chancellor between 1515 and 1529, during the reign of King Henry VIII. Today, a bronze statue of Wolsey in his home town of Ipswich, located in the east of England, features a familiar face peering out from behind his robes – the four-legged su-purr-visor of all that went on in the Tudor court.

Historian Claire Ridgway notes that cats were not a popular pet at the time due to their association with the Devil and witchcraft. It is an urban myth that Pope Innocent VIII decreed cats as unholy creatures in 1484 and that they should be torched alongside the witches that owned them. When witches were burned at the stake, it was often said that a black cat leapt out of the flames. 4

Nonetheless, Wolsey clearly held his cat dear, and though it was the first pet ever recorded at the centre of government, it was likely animals, and cats in particular, had been part of politics in Britain for many years before.

Sir Richard Whittington (1354–1423), for example, is well known for his own furry companion through the popular folk tale of Dick Whittington and his cat. The story goes that Dick, a penniless orphan, became Lord Mayor of London in the fifteenth century. He began life as a servant and his master asked each of his employees to surrender their most valued item to a sea captain who would go abroad and sell that item. Dick was of course reluctant to part with his cat. But the sacrifice worked when the King of Barbary, whose palace was overrun with mice, bought the cat for a large sum of money. With his fortunes on the rise, Dick had the means to become Lord Mayor of London.

There is a statue of his famous cat in Highgate Hill in London and, while there is no substantive evidence that the real Dick Whittington was poor, an orphan or even had a cat, the tale is told in pantomimes and story times across the United Kingdom and beyond to this day. Oh yes it is!

In more recent history, in Victorian England, Tom the cat lived at Downing Street from around 1878 to 1892 during the periods of office of Benjamin Disraeli, William Ewart Gladstone and Robert Gascoyne-Cecil. A number of senior politicians were known to pet Tom, not least Gladstone himself. Sadly, Tom, according to the Manchester Evening News on 22 January 1892, was ‘to the general grief of the inhabitants in the vicinity … set upon by two bull terriers and, after a brave fight, was killed.’

Dr Patrick Little, senior research fellow at the History of 5Parliament project, points out that leaders such as Oliver Cromwell in the seventeenth century used the image of the ‘country squire’ to bolster, or even spin, their social origins. Cromwell was really more farmer than squire: the historian Lady Antonia Fraser writes of Cromwell in St Ives in the early 1630s as ‘farming his cattle, bringing up his family, and showing himself a solid local man’. His affinity with animals was used to portray him as a man of the people.

Many British politicians throughout the ages have used animals to soften their image with the public – or, in Cromwell’s case, create it. Certainly, in the political world from which many feel excluded, the ordinariness and relatability of animals has provided a way for people to engage with politics. A prime contemporary example of this is Larry the Downing Street cat (fear not, he has a chapter all to himself later) who has hit the headlines many times, but even over a century ago, there was great press – and public – interest in the cats of Westminster.

In January 1903, during Arthur Balfour’s premiership, the Dundee Evening Telegraph ran the headline ‘Lost! The Downing Street Cat’ and asked if anyone had seen Topsy. She had clashed with the Chancellor of the Exchequer’s cat Tom, having beaten him ‘in the best of three rounds’. Topsy ‘was a general favourite … a good cat of her claws’, but she disappeared after the fight, leaving Balfour bereft and Tom ‘inconsolable’ too.

In 1907, the society magazine Tatler featured a detailed article on ‘Cats in Office: Mieous from Whitehall’, which explained the difference between the two types of resident feline.

The office cat, said Tatler, ‘seldom has any locus standi [legal standing] and lives on charity all year round’ whereas the official 6cat ‘is a recognised member of the community and has a fixed allowance for food and other necessities’. As part of the article, Tatler photographed seven of these cats in and around government buildings: Tommy Liza the Privy Council cat, Toby the Home Office cat, Joe the Board of Education cat, Tits and Tats the Mansion House cats, Trillie Williams the War Office cat and Duke, the Paymaster General’s cat.

Tommy Liza was ‘always in disgrace in spite of his sixteen years’, and his ‘favourite resting place’ was the chair of the Marquess of Crewe, Lord President of the Council from 1915 to 1916. Toby was ‘the Home Office cat, eleven years old and a sufferer from chronic asthma’. Joe was a ‘terror to the pigeons living nearby’. Tits and Tats, reported Tatler, were ‘lively youngsters’ who ‘evinced a great dread of the camera and, like the small infant, [had] to be held in position to have their photograph taken’. Trillie Williams was nine years old, continually sleepy and had a ‘preference for the cook’s bed’. Last came Duke, the Paymaster General’s cat, who was a present from the Duke of Wellington, hence his name, and was very energetic.

There weren’t just cats – or indeed dogs – living in Downing Street at this time. Sir William Harcourt kept a canary at No. 11, the official residence of the Chancellor of the Exchequer, while he held the title between 1892 and 1895. According to the Oxford Chronicle and Reading Gazette, the bird ‘escaped a few years before the General Election in 1895’ but ‘was recaptured soon after’ its bid for freedom. Prime Minister David Lloyd George’s dog went missing in 1918, with the Croydon Times reporting his Welsh terrier Cymro had been ‘lost at Sutton on 19 July whilst Mr Lloyd George was addressing a War Weapons Campaign 7meeting’. According to the Daily Mirror eleven days later, a resident of Redhill claimed the £5 reward having found the dog ‘wandering around’ and temporarily given him a home. Frilly was the British War Office cat some time around 1909. When he died, the office staff had a whip-round to pay for him to be stuffed, and he was displayed in the Imperial War Museum’s exhibition ‘Animals’ War’ in 2017.

‘If you look at the records, there is very much an idea that in the 1920s, these are working animals,’ Christopher Day, author of Larry the Chief Mouser: And Other Official Cats, told Politico in 2023. ‘They were being paid for out of public funding – which is not the case now – and they were expected to earn their keep.’

Not all the animals were politicians’ pets, however. On 8 June 1923, a dog made its presence felt to a House of Commons committee discussing street betting. The Daily Herald reported how a black and white terrier ‘quietly strayed into the room in Westminster Palace, and, unobtrusively stalking about the tables, made a mute appeal to members … he was stroked and petted by a number of the MPs’.

As war loomed in 1939, Bob the Downing Street cat was thought to be a sign of good luck. He had been spotted during the signing of the Munich Agreement the year before and was seen again just days before the outbreak of the Second World War. The Dundee Courier wrote:

The famous black cat which has given a homely touch in Downing Street in times of international crisis reappeared yesterday afternoon. It walked nonchalantly up the street, and as it reached the door of No. 10 there was a cheer by 8the onlookers. When photographers rushed forward the cat turned round and scampered out of sight.

By the time Bob died in August 1943, he had become one of the most photographed cats in the world.

Churchill first became Prime Minister in 1940. He recognised, as have many who have worked in the aged buildings of Whitehall and Westminster, that rodent infestations can be dealt with by employing cats. However, Churchill didn’t limit himself to cats – more on that in Chapter Two.

While there were clear indicators of official versus unofficial cats in Whitehall, it appears the role of chief mouser of the United Kingdom dates back to at least 1924. The first to take on this role was a marmalade cat who had two names: Smokey and Rufus of England. The Chancellor of the day, Philip Snowden, had a reputation for being parsimonious; nevertheless, upon noticing a rather thin-looking Smokey/Rufus one day, decided to increase the cat’s rations by half. But in order for this to happen, a bill had to be passed in Parliament first. This led to the cat acquiring yet another name: Treasury Bill. Treasury Bill was a formidable mouser and ratter and was known to bring ‘trophies’ to his boss. When the cat realised that these thoughtful gifts were being thrown into rubbish bins, he started to leave the dead mice neatly laid out beside the bins for the cleaners. A considerate feline.

In 1936, the Cabinet Office argued that Jumbo, their resident mouser, deserved an allowance. When he died eight years later, the world was at war and men needed at the front, so one Cabinet Office wag suggested that Jumbo’s successor should be 9female, given that women were doing so many of the jobs that men had done previously.

Historians disagree on which was the first official government cat, but we do know that Peter lived in the Home Office from 1929 to 1946. His upkeep was funded by voluntary contributions from civil servants, as is the case for the cats of Whitehall today. He was so loved, and indeed spoiled, that he was not particularly good at the serious business of actually chasing mice. (It appears the pattern started early on this point – Larry, we’re looking at you.) To tackle the issue, the Home Office asked the Treasury for a formal food budget to limit Peter’s overindulgence, get him into shape and to allow him to turn his paws to the role which was supposedly his raison d’être. One penny a week was agreed for Peter’s upkeep.

Peter performed his duties well under this new regime. Indeed, when a section of the Home Office moved to Bournemouth during the Second World War, Peter was so missed that staff there applied for an allowance to keep two cats. They penned a poem in February 1941 to put forward their intriguing suggestion:

Establishments approval seek

To spend say one and six per week

For beverage and food (ersatz)

On each of Bournemouth’s office cats.

This situation is complex

Because we do not know their sex.

To pay for grub we hesitate,

For ‘pussies’ who may propagate.

But if they’ll give a guarantee 10

They won’t produce a family

Of little ‘mousers’ of their ilk,

We’ll meet the cost of food and milk.

A senior civil servant reviewing the proposal wrote to his superiors: ‘Subject to the proviso in the third stanza, I think approval should be given.’ Alas, in 1946, at the age of seventeen, Peter was put to sleep.

His successor was Peter II, a two-month-old male kitten. But the sequel sadly did not last as long as the original as Peter II was tragically run over on Whitehall in June 1947. Three days later, police constable N. Hawe wrote to the Office Keeper, Mr McMillin:

Sir,

At 3.15 a.m. on 21 June 1947 the P.C. on duty outside the Home Office brought to the door ‘Peter’ (H.O. Cat), which, just previously when crossing the road to the Cenotaph, was run over by a motorcar driven by Mr. R. B. BISGOOD 8. Welbeck Street. W1.

The cat received injury to the head, right shoulder and a lacerated jaw; at 3.20 a.m. I telephoned the Night Service, R.S.P.C.A. 105 Jermyn Street. (Whi. 7177.), at 3.35 a.m. their representative attended. After a careful examination he advised that it was for the best to have him put to sleep; to which I, rather reluctantly, agreed. Mr. Bisgood gave two shillings for the services rendered, receipt attached.

N. Hawe P.C. 365.

Just two months later, a successor to Peter II was found, with the highly original name Peter III. He joined the Home Office on 1127 August 1947. Peter III appeared on the BBC in 1958 and was pictured in newspapers and magazines, including the October 1962 issue of Woman’s Realm. His rations were controversial, too, but for a different reason: many members of the animal-loving public believed them to be meagre. One even wrote to the Home Office and received the following reply:

The mice which Peter is employed to catch are not mere ‘perks’; they are intended to be, and should be, his staple food … Peter’s emoluments [salary] are not designed to keep him in food: if they were, they would also keep him in idleness.

Peter III received much fan mail throughout his life, and many messages of condolence were sent to the Home Office when he was put to sleep on 9 March 1964. One letter came from the New York Transit Authority’s ‘Etti-Cat’, a moggy whose job was to promote courtesy on the city’s subway. Many letters also came from Italy where, for some reason, Peter III was particularly loved and missed. To mark his passing, Home Office staff raised money to pay for a headstone at the People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals pet cemetery in Ilford, Essex.

Presumably because calling his successor Peter IV would have been too predictable, the name was feminised to Peta. She was a Manx cat and gift from the lieutenant governor of the Isle of Man. Day describes Peta in his book as ‘inordinately fat and lazy because she’d been fed so many treats’. According to Day and Marianne Whitworth in a National Archive blog post, Peta once got into a fight with Nemo, Harold Wilson’s male point Siamese and, in attempting to break up the cats, Mary Wilson, the Prime Minister’s 12wife, suffered a cut and reportedly had to cancel a dinner with the Italian Prime Minister when the wound turned septic.

Nemo moved into Downing Street after Wilson’s election and would accompany the family on their annual holiday to the Scilly Isles, off the south-west coast of Cornwall. They were also joined by Paddy, the Wilsons’ golden Labrador. A present from George Wigg, the paymaster-general, Paddy was initially sent to Wilson’s sister’s home in Cornwall with instructions that the dog take an obedience course.

The writer Isabel Wolff recalled upon Wilson’s death in 1995 that he might well have died decades earlier in the Scilly Isles had it not been for a fortunate encounter with her family. In 1973, the Wolffs were on their annual holiday when Isabel heard faint cries of distress coming from the water. She found a golden Labrador, presumably belonging to the man shouting, tied up near the boats on the shore. Her father and brothers raced to the rescue, heaving him onboard and rowing back to shore.

The grateful man explained that he had slipped out of his rubber dinghy trying to get into the launch but hadn’t been able to pull himself back out of the water. He had been there for at least half an hour. Wolff’s father soon realised that he had rescued none other than former Prime Minister Harold Wilson. Wilson was, understandably, embarrassed. He slowly walked off with Paddy, having asked the family to spare his blushes publicly. However, the press got the story about a month later, with headlines including ‘Wilson Rescued in Sea Drama’, ‘Wilson Snatched From Drowning’, ‘Scilly Secret Floats to the Surface’ and, from the Daily Mirror, ‘“My Dog Tipped Me In”’. In her account, Isabel Wolff continues: 13

Mr Wilson’s press secretary, Joe Haines, had blamed Paddy. There was even a photo of the dog captioned ‘The Culprit’! One could see the need for damage-limitation – after all, it was embarrassing for Wilson, not least because Edward Heath was a serious yachtsman – but Paddy, I know for sure, was innocent … Joe Haines made light of the incident. Wilson, he claimed, was in ‘no danger’ and ‘could have swum to the beach’ but was ‘waiting for a friend to turn up’.

Harold Wilson would almost certainly have died. He was fifty-seven, he was overweight, he’d been in the freezing water for more than half an hour and his arms were giving out. The Atlantic currents were very strong, there was no one around, and it was only by the slimmest chance that my father heard his cries. He knew he had had an extremely close shave, but had obviously been persuaded to let the dog take the blame and play down the incident.

In 1974, Wilberforce the cat, dubbed ‘the best mouser in Britain’, arrived at Downing Street from the RSPCA (Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals). He served four Prime Ministers during the ‘pendulum politics’ of the 1970s, starting with Wilson’s second premiership through to Thatcher’s period of office in the 1980s. Thatcher once brought him a tin of sardines from a visit to Moscow, according to her press secretary Sir Bernard Ingham. Sir Bernard, an asthmatic, was allergic to cats and did his best to avoid Wilberforce, but it was easier said than done. ‘Bloody Wilberforce used to sit under my desk and I would have a fit of sneezing,’ he recalled. ‘I hate cats.’

Wilberforce also made an appearance during the general 14election coverage in 1983, when he was held by presenter Esther Rantzen and introduced to BBC viewers. Wilberforce left Downing Street in 1986 after thirteen years of loyal service. He went to live in the country with a retired No. 10 caretaker and he died in his sleep on 19 May 1988.

Away from Downing Street, but still with significant ramifications across Westminster, the 1970s saw a very British scandal unfold in the form of the infamous Jeremy Thorpe affair. Thorpe, in part, was brought down by a dog – a Great Dane named Rinka. The Liberal leader’s case became world famous after he and three co-defendants stood trial at the Old Bailey in 1979 for the attempted murder of Norman Scott. Scott was a troubled young man with whom Thorpe had begun an affair before homosexuality was decriminalised. Despite Thorpe’s attempts to pay Scott off, Scott threatened to go public about their affair, posing a danger to Thorpe and the rising popularity of his party.

The situation spiralled, and a would-be hitman called Andrew Newton was sent after Scott. Newton made several attempts to lure Scott out before eventually persuading him to meet on Exmoor just to talk. Newton objected to Rinka tagging along as he was, ironically, rather scared of dogs. Tragically, Rinka came anyway. What happened next became a stain from which Thorpe’s career would not recover. When the party got to a deserted stretch of the road, Newton took out a gun and shot Rinka in the head, before turning to Scott, saying, chillingly, ‘It’s your turn now.’ However, the second shot failed and, having botched the murder, Newton drove away at speed, leaving Scott with his dying dog. The West Somerset Free Press reported the Rinka tragedy under the headline: ‘The Great Dane Mystery: Dog-in-a-Fog Case Baffles Police’. 15

Thorpe was charged alongside three others with conspiracy to murder Norman Scott, and though he was later acquitted, his reputation was ruined. Thorpe resigned as leader of the Liberal Party and lost his seat in the 1979 general election. Auberon Waugh stood against him in his North Devon seat, running as the candidate for the Dog Lovers’ Party, receiving seventy-nine votes.

Of course not all stories involving political animals are nearly as dramatic. Another tale emerged in September 1995, this time not at Downing Street, but John Major’s constituency home in Huntingdonshire. Although a tough time politically for Major, he made his rival party leaders Tony Blair and Paddy Ashdown laugh uproariously during the Victory in Japan Day commemorations when recounting how a goldfish in his pond needed medical attention after becoming sunburned. The fish, reported the Aberdeen Press & Journal, ‘was taken from its watery living quarters and an attempt was made to revive it – using sun cream’. It is not known whether the fish survived.

Humphrey the cat came to Downing Street in 1989 and faithfully served both the Thatcher and Major administrations before leaving under something of a cloud during Tony Blair’s first year. Like Bob, the ‘omen of good luck’ about fifty years earlier, Humphrey arrived as a stray, having been originally found wandering the streets by a Cabinet Office civil servant a few months after the death of the previous mouser, Wilberforce. He was named after Sir Humphrey Appleby, Nigel Hawthorne’s fictional Permanent Secretary in the TV comedies Yes, Minister and Yes, Prime Minister. The Cabinet Office’s previous pest controller charged £4,000 per annum. At just £100 a year, Humphrey was 16much more economical. In 1993, a Cabinet Office memo told civil servants that Humphrey had a kidney complaint. ‘As well as being treated by a vet he has been placed on a controlled diet and is not to eat anything other than the prescribed food,’ the Cabinet Office memo read. ‘Staff are therefore asked that, for his own good, he is not fed any treats or titbits.’ An earlier memo, prepared by the accommodation officer at the Cabinet Office at 70 Whitehall, explained:

He tends to eat little and often – no doubt because he knows he can always get food whenever he wants … He is a workaholic who spends nearly all his time at the office, has no criminal record, does not socialise a great deal or go to many parties and has not been involved in any sex or drugs scandals that we know of.

Humphrey also technically ‘belonged’ to the Cabinet Office rather than the neighbouring No. 10, but as any owner will tell you, cats don’t usually answer to anyone other than themselves. His food budget came out of the Cabinet Office’s funds, yet he was frequently found on Downing Street. One of his favourite ways to spend his time was to sit on top of the hot air vent just outside the front door of No. 10, something Larry still does.

In spring 1994, Humphrey was accused of the murder of four robin chicks near the Prime Minister’s Office. However, the cat had his defenders, not least one civil servant who argued in a memo that Humphrey ‘could not have caught anything even if it had been roast duck with orange sauce presented to him on a plate’. They insisted that the four robins in the window box had 17perished via other means: ‘This was a libellous allegation and was completely unfounded. This was at a time when Humphrey, a gentle-natured cat, had been ill with kidney trouble and sleeping for most of the day.’

A London newspaper requested an interview with Humphrey about the robin controversy but they were denied: ‘Unfortunately as Humphrey is a civil servant he is bound by civil service rules and cannot talk to the press about his position.’ Prime Minister John Major soon exonerated Humphrey, stating to reporters, ‘I am afraid Humphrey has been falsely accused.’ In 2006, George Jones, the Daily Telegraph journalist who wrote the story, admitted that he had made it up. Jones had indeed been shown the dead robins by Major on a visit to Downing Street, but there was no evidence to suggest that it was Humphrey who had caused their death. Yet, proving that mud sticks, later that year Humphrey was accused of having ‘savaged’ a duck in the nearby St James’s Park.

Much like Larry, Humphrey was described as a very relaxed, laid-back cat, unperturbed by the great matters of state around him or the famous people, flashbulbs of photographers and general fuss that occurs at Downing Street. On one occasion, King Hussein of Jordan was kept waiting while a police officer removed Humphrey from the red carpet. When American President Bill Clinton came to visit, Humphrey felt the need to go over and investigate the presidential Cadillac and came close to being run over in the process.

Despite, or perhaps because of, these news-grabbing mishaps, a cat food company requested that Humphrey star in its adverts but, according to the Daily Record, was told ‘paws off’. Apparently, as Humphrey was a civil servant, it would be against his 18contract to take advertising work. His likeness, however, did appear on the small screen, satirised in the TV comedy series Spitting Image as a cat who criticised Sir John Major. However, there is no evidence to suggest Humphrey and Major ever got on anything other than very well.

In June 1995 Humphrey performed a vanishing act, only returning some months later. No. 10 had kept his disappearance quiet until a journalist on The Times, Sheila Gunn, told a member of staff there that her own cat had died. Conversation then turned to the missing Humphrey and the story was made public. Finally, in September, the Daily Mirror reported that ‘Humphrey the Downing Street cat has been found safe three months after disappearing’. There were some red faces at The Times newspaper, which had already printed his obituary. It transpired that a policeman at the Royal Army Medical College, about a mile from Downing Street, had found Humphrey, thought he was a stray, took him in and called him PC, short for ‘Patrol Cat.’ Eventually, the policeman recognised Humphrey’s photo and the cat was returned to his Downing Street home.

Safely back in No. 10, Humphrey issued a statement via the civil service: ‘I have had a wonderful holiday at the Royal Army Medical College, but it is nice to be back and I am looking forward to the new parliamentary session.’ He even received a message of support from Socks, America’s ‘First Cat’, welcoming him back. Socks, himself a popular political animal, belonged to the Clintons and ruled the roost at the White House.

This was not the only time that Humphrey found a new home, however. He was quite innocently catnapped by a member of the public in 1997. A German travel agent, Hanni Velden, spotted 19Humphrey wandering around St James’s Park, something he did fairly often. Velden mistakenly thought Humphrey was a stray, picked him up and brought him to her flat in Lambeth, south London. She subsequently took him to the vet for a check-up whereupon someone else recognised Humphrey. The Cabinet Office was given a call to check whether he was missing, they confirmed that he was and Humphrey was returned.

But trouble lay ahead. Later that same year, Humphrey was ‘retired’ shortly after Tony Blair became Prime Minister and his family moved into Downing Street. Initial reports suggested that Cherie Blair, the Prime Minister’s wife, was either allergic to cats or believed them to be unhygienic. This was later revealed to have been an invention of a press adviser to Major. ‘One of the first things the children wanted to see when they moved into No. 11 was Humphrey,’ a spokesman said at the time, denying the allegations. ‘Cherie and her sister had both a cat and a dog when they were growing up. This is Humphrey’s home and, as far as the Blairs are concerned, it will remain his home.’ Curiously for a statement released to the media under the watch of communications director Alastair Campbell at No. 10, the latter part didn’t prove to be fully factual. The Press Association was invited to take a photo of Cherie Blair with Humphrey in her arms, proving just how much they truly loved one another; neither appeared particularly happy to be there (see photo section). Tony Blair later admitted it was the biggest political crisis of his first year as Prime Minister.

But Humphrey’s retirement was more about his advancing years than any conspiracy to get rid of him by Mrs Blair, Campbell or anyone else, however convenient it was for them to be 20portrayed as pantomime villains of the piece. In early November 1997, Humphrey’s primary carer, a civil servant called Jonathan Rees who worked in the No. 10 Policy Unit, wrote a memo suggesting that the ageing cat should be allowed to retire to a ‘stable home environment where he can be looked after properly’. A vet agreed, especially as Humphrey’s kidney complaint had persisted and he had lost interest in food.