8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

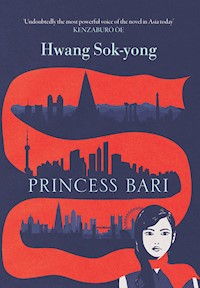

- Herausgeber: Periscope

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

In a drab North Korean city, a seventh daughter is born to a couple longing for a son. Abandoned hours after her birth, she is eventually rescued by her grandmother. The old woman names the child Bari, after a legend telling of a forsaken princess who undertakes a quest for an elixir that will bring peace to the souls of the dead. As a young woman, frail, brave Bari escapes North Korea and takes refuge in China before embarking on a journey across the ocean in the hold of a cargo ship, seeking a better life. She lands in London, where she finds work as a masseuse. Paid to soothe her clients' aching bodies, she discovers that she can ease their more subtle agonies as well, having inherited her beloved grandmother's uncanny ability to read the pain and fears of others. Bari makes her home amongst other immigrants living clandestinely. She finds love in unlikely places, but also suffers a series of misfortunes that push her to the limits of sanity. Yet she has come too far to give in to despair - Princess Bari is a captivating novel that leavens the grey reality of cities and slums with the splendour of fable. Hwang Sok-yong has transfigured an age-old legend and made it vividly relevant to our own times.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Hwang Sok-yong

PRINCESS BARI

Translated from the Korean by Sora Kim-Russell

Princess Bari

First published in Great Britain in 2015 by

Periscope

An imprint of Garnet Publishing Limited

8 Southern Court, South Street

Reading RG1 4QS

www.periscopebooks.co.uk

www.facebook.com/periscopebooks

www.twitter.com/periscopebooks

www.instagram.com/periscope_books

www.pinterest.com/periscope

Copyright © Hwang Sok-yong, 2015

The right of Hwang Sok-yong to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher, except for the quotation of brief passages in reviews.

This English translation copyright © Sora Kim-Russell, 2015

The translation of this book was supported by the Daesan Foundation.

ISBN 9781859641767

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This book has been typeset using Periscope UK, a font created specially for this imprint.

Typeset bySamantha Barden

Jacket design by James Nunn: www.jamesnunn.co.uk

Printed and bound in Lebanon by International Press:

Many small stars fill the blue sky, and many worries fill our lives.

Jindo Arirang [Korean folk anthem, variation from the Jindo region in South Korea]

Contents

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

New from Periscope in 2015

One

I was barely twelve when my family was split apart.

I grew up in Chongjin. We lived in a house at the top of a steep hill overlooking the sea. In the spring, clusters of azalea blossoms would poke out from among the dry weeds, elbowing each other for space in the vacant lots, and flare a deeper red in the glow of the morning and evening sun as Mount Gwanmo, still capped with snow and cloaked in clouds from the waist down, floated against the wide eastern sky. From the top of the hill, I watched the lumbering steel ships anchored in the water and the tiny fishing boats sluggishly making their way around them, the rattle of their engines just reaching my ears. Seagulls shattered the sunlight’s reflection on the surface of the water, which glittered like fish scales, before wheeling off into the sun itself. I used to wait there for my father to come home from his job at the harbour office or for my mother to come back from market. I would leave the road, scramble up a steep slope and squat at the edge of the cliff, because it was a good spot to watch out for them, but also I just liked looking down at the sea.

We had a full house: Grandmother, Father, Mother, my six older sisters. Most of us had been born within a year or two of each other, which meant our mother was pregnant or nursing for practically fifteen years straight. The moment one girl popped out, she was waddling around with the next. My two oldest sisters never forgot the fear that filled our house each time our mother went into labour.

Luckily, Grandmother was by her side each time, acting as midwife. They told me our father used to pace back and forth and chain-smoke outside the door or out in the courtyard, but after the third girl was born, whenever our mother showed signs of going into labour, he stayed late at work instead and even volunteered for the night shift. The anger he’d been suppressing finally exploded when Sook, the fifth girl, was born. That morning, Mother and Grandmother were in the main room off the kitchen, bathing newborn Sook in a tub of warm water, when Father returned home from night duty. He opened the door, took one look inside, and said: “What’re we supposed to do with another of those?” He yanked little Sook from their arms and shoved her head under the water. Shocked, our grandmother hurriedly fished the baby from the tub. Sook didn’t cry, but just spluttered and coughed instead as if she’d swallowed too much water and couldn’t breathe. When the sixth girl, Hyun, was born, Jin, the oldest, wound up with a brass bowl of kimchi on her head as she was coming back from the outhouse just as our father vented his anger by tossing the breakfast tray into the courtyard.

So what do you figure happened when I was born? Jin told me: “We all crowded into the corner of the kids’ room and shivered in fear.” After they heard the newborn’s first cry, Sun, my second-oldest sister, crept out to investigate, only to return pouting and crying.

“We’re doomed! It’s another girl.”

Jin warned everyone: “Not a peep out of any of you, and don’t even think about stepping foot out of this room until Father gets home.”

Grandmother, who caught me when I was born, wrapped me in a blanket, my skin still covered in blood and fluid, and then sat vacant-eyed on the dirt floor of the kitchen, too much at a loss to even think of boiling up a pot of seaweed soup for our mother. Mother cried quietly to herself; then, after a little while, she picked me up and carried me out of the house to a patch of woods a long way from our neighbourhood where no one ever went. There she tossed me into some dry underbrush among the pine trees, and covered my face with the blanket. She probably meant for me to smother to death, or to freeze in the cold morning wind.

When Father got home, he opened the door without a word. Of course, he could tell from the mood in the house – Mother had the blanket up over her face and was unresponsive, and Grandmother just coughed drily now and then from her spot in the kitchen – that he had no hope of ever getting a son, and he turned heel and left. Mother and Grandmother each stayed put in their stupors, one inside and one out in the kitchen, until the sun was high in the sky. Finally, Grandmother went back inside.

“What happened to the baby?”

“Don’t know. Must’ve crawled away on its own.”

“Why, you threw it out! You’ll be struck dead by lightning for this, you stupid girl!”

Grandmother searched the house inside and out, but I was nowhere to be found. Fearful of how Heaven might curse them, and filled with pity for her daughter-in-law and poor little granddaughters, she filled a porcelain bowl with cold water, placed it on a small, legged tray and sat out back, rubbing her palms together in prayer.

“Gods on Earth, gods in Heaven, I pray to you, lift the bad fortune from this home, bring that baby back in one piece, turn the poor mother’s heart, calm the father’s anger and keep us all safe.”

Grandmother finished praying and searched the house again and all over the courtyard and the surrounding neighbourhood, before finally giving up and returning home. She sat despairingly on the twenmaru, the narrow wooden porch that lined the house, when our dog Hindungi suddenly poked her head out of the doghouse and stared up at her. As Grandmother turned to look at the dog, her eye caught a tiny corner of the blanket she’d wrapped me in. Hoping against hope, she dashed over to the doghouse and peeked inside: Hindungi was lying down, and there I was, bundled up and nestled between her paws. Grandmother said my eyes were closed, and I was snuffling in my sleep. Hindungi must have followed our mother when she left the house to get rid of me, slinking behind at a careful distance, and then caught my scent and hunted through the underbrush before picking me up in her jaws and carrying me home.

“Aigo, our Hindungi is such a good dog! This child was sent to us from Heaven, I’m sure of it!”

Maybe that’s why I felt closest to my grandmother and our dog when I was little. Hindungi was named for the white fur that her breed, Pungsan, was known for, but I myself didn’t have a name until my hundredth day, when babies are said to be fully among the living and I was sure to survive infancy. It hadn’t occurred to anyone to give me one. Later, after our family was dispersed in all directions and my grandmother and I were living in that dugout hut on the other side of the Tumen River, she told me a story she’d heard long, long ago from her great-grandmother. It was the story of Princess Bari, whose name meant “Abandoned”. She would always finish the story by singing the last lines to me:

“ ‘Throw her out, the little throwaway. Cast her out, the little castaway.’ So that’s how you got the name ‘Bari’.”

In any case, for a long time I didn’t have a name. Grandmother brought it up while we were eating one day. We were sitting at the round tray with Mother, after Father and Grandmother were served their food at the square tray.

“I mean, really!” Grandmother confronted Father out of the blue. “Why doesn’t that baby have a name yet?”

Father slowly ran his eyes over the children clustered around the table, as if counting us one by one.

“Well,” he said, “I know there are enough girl names for twins, all the way up to sextuplets … but what am I supposed to do after that? I only know so many characters.”

“You mean to say you went to college and can speak Chinese and Russian, but you can’t come up with a name for your baby girl?”

This was back when the Republic was still generous, so whenever twins were born, regardless of whether they were in a big city or a remote country village, reporters would show up from the TV stations and newspapers and the babies would appear on the evening news. Thanks to the country’s strong welfare system, babies were cared for in state nurseries and mothers received ample rations of powdered formula, and the Great Leader himself would thank the parents and shower them with gifts, from baby clothes to toys. Quadruplet girls were named after the four noble plants of classical Chinese art – Orchid, Bamboo, Chrysanthemum and Plum Blossom – and there were probably similar matching names for quintuplets and sextuplets. That’s what our father meant when he said he had only been prepared for six girls. My sisters’ names – Jin, Sun, Mi (Truth, Goodness and Beauty) and Jung, Sook, Hyun (Grace, Virtue and Wisdom) – came in sets of three, and no more. Our father probably thought that my being born a girl had turned those complete and perfectly matched names into a meaningless jumble of letters. He had nothing more to say about it. But since the subject had been raised, Grandmother and Mother kept talking after he left for work.

“Little Mother, maybe it’s time we gave it a name,” Grandmother said.

“Name her ‘Sorry’ or ‘Letdown’, because that’s how I feel. Sorry and let down.”

“I have heard of names like that before, but let’s see. You tried to abandon her in the woods …”

And that’s how my grandmother came up with my name. Of course, it wasn’t until much later, after I’d gone to the ends of the Earth and suffered every kind of hardship, that I understood exactly why she named me “Bari”.

*

Our father was raised by his widowed mother. Grandfather died in a war that started long before I was born. Grandmother claims he was a war hero, and that his story had even made its way onto one of the central radio station’s broadcasts. In some faraway seaside town way down in the south, Grandfather had fought off a troop of Big Noses, and singlehandedly at that, as they were rolling in on their tanks. Grandmother would often retell the story after dinner when the trays had been put away, or on summer nights when we would spread out straw mats in the front courtyard and gaze up at the stars. But one night Father got so fed up with hearing it that he butted in, and the heroic tale of my grandfather lost its shine.

“Enough already! Stop it with your stories. That’s all straight out of a Soviet film.”

“What film?”

“That film we saw in town. Don’t you remember? The neighbourhood unit went to see it as a group. You’re mixing it up with Father’s story.”

The plot of the film went like this: a young soldier, still wet behind the ears, falls asleep while standing guard beneath a collapsed building in a shelled-out city. At dusk, his unit retreats, leaving him behind and still fast asleep. Meanwhile, enemy troops roll right in under the assumption that the ruined city has been evacuated. The soldier is startled awake by the noise. He sees tanks, the headlights of army vehicles and the shadowy figures of enemy soldiers coming down the main strip. Terrified, he aims his submachine gun, pauses in absolute bewilderment and pulls the trigger. The tanks stop, and for a moment all is silent. The soldiers halt in unison, then turn and retreat: they believe their enemy is waiting to ambush them in the dark. Only then does the soldier crawl out from the rubble and take off running. He runs all night, and manages to catch up to his unit around daybreak. He’s called before the platoon leader, then the company commander and finally the general, who praise him each in turn and later bestow him with a medal. He’s named a hero for singlehandedly stopping an enemy division, and is rewarded with a special furlough.

Anyway, from what our father told us, it was probably true that Grandfather had been killed in combat on the eastern front. He said Grandmother was called before the People’s Committee and given official notification of his death along with some extra rations in recognition of his services, and when Father went to school, his homeroom teacher had him stand at the podium while she made the students offer up a moment of silence. But Grandmother had already known exactly when Grandfather had died, and had fixed the date for the anniversary of his death so the family would know when to observe memorial rites every year. As always, she had seen what was coming in her dreams.

Late one night, Grandmother heard Grandfather’s familiar cough outside and opened the door. A ray of moonlight shone down on the courtyard, and in it stood Grandfather in a torn military uniform. She asked him where he’d been, and he said he’d walked up the east coast, through the towns of Mukho, Gangneung, Sokcho, over twenty mountains, maybe more, to get to her. He was carrying a bundle of some sort under his arm, so she told him to set it on the twenmaru and come on in, that she would make breakfast for him in the morning; but he said he had a long way to go still, and he kept his shoes on and remained standing. Grandmother quickly took his bundle and set it down, but when she turned back, he had vanished. The courtyard was empty. She awoke with a start and put her hand out. There was something on the floor next to the bedding. When she turned on the lamp to examine it, the wardrobe doors were hanging open and some clothes had spilled out: Grandfather’s padded pants and jacket and the rabbit fur-lined vest he had taken off and stashed in the closet before leaving for the army. That night she hastily scrounged together a bottle of alcohol, dried pollock and some fruit for his memorial table to give him a simple sending off, and burned his clothes to send him on his way.

Grandmother saw ghosts sometimes, and could even hear the nonsensical conversations they had. Ever since our father was young, she would set out a bowl of clean, freshly drawn well water behind the house and pray before it to the gods, but after such things were outlawed by the Republic, she stopped doing it outside and would squat on the dirt floor of the kitchen and pray there instead. Mother and Father tried to stop her at first, and the two of them would get into fights about it.

“Aren’t you supposed to stop her when she starts up with that black magic?”

“Aigo! Do you really think your mother’s going to listen to me? She scares me with all that ghost talk. I don’t dare say a word about it. Besides … doesn’t it run in your family?”

“What do you mean, ‘runs in my family’?”

“Well, she said your great-great-grandmother was a shaman in Hamheung.”

“Watch your mouth! Don’t you know what kind of trouble we could get in if you start spreading that nonsense around?”

“But when I married you, everyone in your village knew that your great-grandmother and your great-great-grandmother were powerful shamans before Liberation …”

“Damn it, woman! Keep it down! We’re descended from poor farmers. That means we’re part of the core class.”

Grandmother said that Father had been a good student ever since his days at the People’s Primary School. Right after the war, when the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army was still stationed in the city, he had picked up some Chinese here and there and would even go to the base with the older folk to help settle civil complaints. He graduated first in his class from secondary school and even received a recommendation to attend university in Pyongyang.

Our parents wound up married to each other due to our grandmother’s meddling. Father had completed his labour mobilization during summer break from his first year of university, and found a spare week to return home for a visit only to discover a girl waiting there for him.

He stepped through the gate and called out: “Mother, can you bring me some cold water?” Who should come out of the kitchen then but this short, bob-haired girl carrying a bowl of water with both hands …

He forgot all about the water and stared at her stupidly before finally asking: “Who’re you, Comrade?”

Grandmother answered for her.

“Who do you think? That’s your wife.”

Father practically jumped out of his skin at that and ran for the station, where he hopped the first train for Pyongyang. About a month later, he was ordered to report to the academic affairs office. The professor in charge of monitoring the students stood with his cheeks puffed out and studied him for a moment before gesturing with his chin for him to sit down.

“I didn’t think you were the type, Comrade – only a student, but already you’re married … Now, I know your mother’s a widow and girls run in your family, so I understand why you want to get started as soon as possible and try for a son. But explain to me why you abandoned your wife.”

Father, flabbergasted, started talking gibberish.

“No, uh, it’s not like that, you see, I went home for a short visit and out of the blue my mother said I was married so I hurried back to school and –”

Just then the door cracked open, and Grandmother stuck her head in.

“Hey! We’re here,” she said, and stepped inside. Then she glanced back at someone and said: “Well, come in already.”

The bob-haired girl followed her in, head hanging down, and bowed wordlessly at the professor. Father’s face turned bright red. He got up without saying a word.

“We don’t need to discuss this any further,” the professor said. “I’ll issue you a pass so you can escort your mother home. You’re married now. Time to go home and consummate it.”

“I have to finish school first …”

“You should’ve thought about that before you got married! Go on, now. If you stick around any longer, I’ll have to tell your comrades. If the Youth Association gets wind of this, you’ll be marked as a bad element, maybe even as a decadent, and you’ll be expelled.”

So that was how Father wound up being dragged back to Chongjin. From the moment they boarded the train, Grandmother started laying down threats.

“No more running around from now on. This union was arranged by my guardian spirit, so if you don’t do as I say, we’re through. You’ll go your way, and I’ll go mine.”

Grandmother produced a baby sling from somewhere and tied one end around Father’s leg where he was sitting. Then she tied a round knot into the sling and held it up to Mother’s ankle.

“Lift your foot, girl. Slip it through this.”

Mother took off her rubber shoe, pulled up her sagging sock, and said: “Make it tight.”

Father told us that when he turned his head to see what the two women were doing, Mother met his eye and stuck her tongue out at him. (Right up until we were all separated, any time that story happened to come up when they were fighting, Father would burst out: “I should’ve chopped my leg off and run away to start a new life back when I had the chance!”) Grandmother wrapped the free end of the sling around her wrist several times and then let out a long sigh, as if she could finally relax. At this point in the story, my sisters and I would ask her: “Why did you decide to make Mother your daughter-in-law?” Grandmother would tell us about the dream she’d had, and how she had gone to our mother’s village to find her.

“I dreamed that a celestial maiden fell out of the sky and landed with a loud thud right on top of the house. She rolled off the roof and into the courtyard. I called out: ‘Hello, hello, if you’re a ghost, then back off, and if you’re a person, then be on your way.’ But she told me she had tended the garden of the Great Jade Emperor in his heavenly palace, and that she’d been dropped to Earth as punishment for overwatering the flowers and causing them to fall from their stems.

“I glanced around the courtyard, and sure enough, there were exactly seven flowers lying on the ground. She picked them up one by one and offered them to me. I put out my hand to take them, but before I could, that crazy girl opened the gate and took a hop, skip and a jump backwards and ran off. I ran after her. I chased her all the way to a sorghum-stalk fence in front of someone’s house, and then I woke up.

“The dream was so strange that I went outside to take a look. The road the celestial maiden had taken led to the next village. I wound my way down the road just like I had in the dream, and ended up at a house surrounded by a sorghum-stalk fence and thought: How curious is this? When I went into the yard, a girl was singing. She was wiping down the large clay jars on the jangdokdae. She had cleaned the soybean paste jars and soy sauce jars to a high shine. From behind, she had a nice rump, and though I’m a woman myself and not a man, that butt of hers was as plump and tantalizing as a peony. So I invited her to come and live with us. I met her parents too and told them all about your father.”

Everyone in the family knew that Grandmother had a strange gift, but Father alone refused to acknowledge it. Nevertheless, whenever it was the end of the year or the start of a new one, or when he woke up in the morning from an unsettling dream, he would stealthily ask her what his fortune held. “Oh, and then,” he would mutter, as if to himself, “this water jar split in two, and a catfish the size of my forearm came wriggling out.”

But not only would Grandmother not interpret his dream for him, she would toy with him by playing stupid: “Mm, we should boil up some catfish stew! Give the whole family a feast.”

Since our mother kept winding up pregnant with another of us while she was still struggling to recover from the last pregnancy and take care of the latest newborn, she wasn’t able to go to work like the other mothers. Our parents must have been more careful after Mi, the third girl, was born, because it was three years before Jung came along. Mother used that time to finally get out of the house. She helped with making side dishes in one of the food factories that had started on the collective farms and in cities and counties across the country during the postwar recovery years; then, later, she was assigned to a recreation centre where she learned hair cutting and styling techniques. After six months, she worked in the barbershop of a public bath in the city.

But because of Father’s and Grandmother’s unquenchable desire for a son and grandson, Mother was only able to work for about a year, including her apprenticeship period, before she had to quit. After the incident where Father held Sook under the bathwater, Mother seemed to give up entirely on the idea of doing something different with her life. Everyone said Sook wound up the way she did after having the measles, but Mother and Grandmother blamed Father for it and talked behind his back about how it was his fault for holding the newborn under water. Up until she’d passed her third birthday, it seemed as if she was just slow to start talking, but then they realized she’d been a deaf-mute all along.

*

I was attending a local kindergarten at the time, so I must have been about five years old. The azaleas had bloomed a bright red at the top of the hill, and my sisters were out filling their baskets with freshly-picked shepherd’s purse, which means it had to be early spring.

I was sitting on the sunny twenmaru porch just off the main room, basking in the warm sun, when Hindungi suddenly crossed the courtyard, heading straight for the front gate and growling. Her ears were folded back, and she bared her teeth and started barking ferociously. Wondering who it was, I went over to the gate and pushed open the wooden door. A little girl, just a bit bigger than me, was standing there. She wore a shin-length mongdang skirt and a jeogori blouse, both made from white cotton. I thought she was one of Hyun’s friends coming over to play. I said: “Hyun’s not home right now,” but the girl just stared straight at me without saying a word. Hindungi was still barking wildly behind me, but the girl didn’t look the least bit scared.

I thought I heard her say: “This isn’t the place.” No sooner did I hear those words than she turned and ran off. Actually, I’m not sure whether she ran away or faded away right before my eyes. I hurried out the gate, wondering where she’d vanished to, and saw that she was already way down at the far end of the path that ran along the other houses, which were all similar in size and shape to ours. Her ponytail swayed back and forth as she went. She stopped in front of a house with an apricot tree in the yard, turned to look my way, and slipped inside. The reason I remember that ponytail is because of the bright red ribbon fluttering at the end of it. That night, while we were all eating dinner, our mother told Father there’d been a death in the neighbourhood.

“We need to give some condolence money to the head of the neighbourhood unit. Her family just lost their grandson.”

“What? How did he die?”

Before Mother could answer Father’s question, Grandmother muttered to herself: “Must have been something in his past life. It’s fate.”

“You don’t think it’s the typhoid fever that’s been going around?”

I tugged on the hem of Grandmother’s skirt to tell her what I’d seen earlier.

“Grandma! Grandma!”

“Yes, yes, let’s eat.”

“I saw something earlier, Grandma. A little girl came to our door and then left. She went into the house with the apricot tree in the yard.”

No one paid any attention, but after dinner Grandmother pulled me aside, sat me down on the twenmaru and asked me a lot of questions.

“Who did you say you saw?”

“A little girl dressed all in white. Hindungi barked at her and tried to bite her. When she saw me, she said, ‘This isn’t the place,’ and left. I wondered where she was going so I followed her outside, and I saw her go into the apricot-tree house.”

“Did you make eye contact with her?”

“Yes! Right before she went in, she turned and looked at me.”

Grandmother nodded and stroked my hair.

“You’ll be all right,” she said. “You’ve got the gift in your blood. Now, do as Grandmother tells you. Spit on the ground three times and stamp your left foot three times.”

That day I became very ill. My body got really hot, and I started talking nonsense. It went on all night. Father carried me on his back to a hospital down near the harbour. Children and old people who’d been brought there from towns and villages nearby were lying in rows in every room. I don’t remember how many days I spent there. All I do remember is seeing that little girl perched on the ledge of the lattice window, close to where several people were lying. I stared up at her. I wasn’t afraid. After I was sent home, my sisters were moved out of the back room where we normally all slept, and my grandmother stayed by my side. She was the only one who would come near me. My fever would dip during the day and then set me afire again at night. Hives the size of millet seeds broke out all over my body and took a long time to go away. Grandmother kept asking me about the girl.

“Do you still see her?”

“No, but I did at the hospital. Grandma, who is she?”

“That’s the typhoid ghost. Nothing will happen to you. My guardian spirit is keeping watch.”

I don’t know how long I was sick. I kept slipping in and out of sleep both day and night. I can still remember the dream I had:

I enter the grounds of what looks like an old temple. A stone wall has collapsed, and tiles from the half-caved-in roof lie scattered about in the reedy, weed-filled courtyard. I don’t go into the darkened temple, but instead stand nervously next to a slanting pillar and peer inside. Something moves. A dark red ribbon comes slithering out of the shadows. I turn and start to run. The ribbon stands on end and springs after me. I run through a forest, wade across a stream and cut through rice paddies, clambering over the high ridges between them, and make it back to the entrance of our village. The whole time, that red ribbon is dancing after me. Just then, Grandmother appears. She looks different – she’s wearing a whitehanbokand has her hair up in a chignon with a long hairpin holding it in place. She pushes me behind her and lets out a loud yell:

“Hex, be gone!”

The ribbon slithers to the ground and vanishes.

I woke up in a panic. My body and face were drenched in sweat as if I’d been caught in a rainstorm. Grandmother sat up and wiped my face and neck with a cotton cloth. “Hold on just a little longer, and it’ll pass,” she said.

Though I was awake, my body kept growing and shrinking over and over as the fever rose and fell. My arms and legs grew longer and longer until they were pressed up against the floor and the walls. Then they shrivelled and shrank up smaller than beans, like rolled up balls of snot dug from both nostrils, and got softer and softer until the skin burst. The warm floor against my back dropped and carried me down, down, down, into the earth below. Faces appeared in the wallpaper. Their mouths opened, and they laughed and chattered noisily at me.

I made it through the typhoid fever, but for several years, right up until I started school, I remained frail. I started hearing things I hadn’t heard before and seeing things that weren’t there before. That was also when I started communicating with our mute sister, Sook. Jung, the fourth-oldest, and Sook, the fifth, were only a year apart and were always at each other’s throats. It was the same with Hyun and me – as she was the second-youngest after me, I never bothered treating her like an older sister and she was always irritated with me because of it. Jin, Sun and Mi were much older than the rest of us, and they were bigger too. After all, a good three years separated Mi and the next one down, Jung. Anyway, Hyun and I were both treated like babies by everyone else, but Jung and Sook were awkwardly positioned in the family. Whenever an errand had to be run, it always fell to them. Between the two of them, Jung was the easier mark. Since Sook couldn’t talk, there was a limit to what she could be ordered to do. For instance, if you told them to run down to the greengrocer at the bottom of the hill and bring back some tofu and green onions, Jung would push her bottom lip out and glare menacingly at Sook.

“I get stuck having to do everything because of her.”

Because she couldn’t communicate through words, Sook was short-tempered. She would get along with everyone fine for a while, doing what she was told, but the moment she lost her temper she was ripping out clumps of hair and kicking in stomachs – big sister, little sister, none of that mattered when she was on the attack. For that reason, our parents did their best to treat Jung and Sook equally. When they bought us clothes, Jung and Sook were given identical styles and patterns, and even pencils were doled out in identical sets of three.

One morning, my sisters were running around getting ready for school, taking turns going to the toilet, washing their faces and combing their hair when Sook began to shriek. Her face turned bright red from screaming, but since she couldn’t speak, no one knew what was wrong. She was holding something in her hand and shaking it: a single scorched trainer. It seemed that the trainer, which had been washed the night before and set on top of the warm, wood-burning stove to dry, had fallen in front of the open flames. Naturally, Sook and Jung wore identical blue trainers. Clever Jung had snatched up the unscathed pair and put them on, claiming they were hers, and left the burned shoe where she’d found it. Sook threw the burned shoe and hurled herself at Jung, grabbing her around the waist and tackling her. Jung squirmed and struggled as Sook pulled the undamaged shoes off Jung’s feet. That was her way of saying they were hers. Unwilling to admit defeat, Jung bit her arm. Their screaming and crying shook the whole neighbourhood. Father, who was steaming with anger, changed his mind about leaving for work and made them line up at the edge of the twenmaru so he could take a switch to their calves.