Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Oldcastle Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

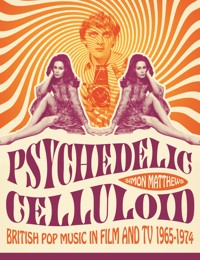

After The Beatles stormed America, every Hollywood and European production company descended on London to be part of the new swinging scene... and they didn't leave until they'd signed up every able-bodied pop group or singer to appear in one of their films. A unique and carefully researched cultural history of UK film, TV and music in the swinging 60s. A time when no film or TV programme was without a group, singer or fantastic soundtrack - and London was briefly the film capital of the world. Containing individual summaries of over 120 films, covering everything from John Barry to Pink Floyd via Blow Up, the Electric Banana, Serge Gainsbourg, Magical Mystery Tour, David hemmings, Kubrick, Godard, Jodorowsdky and the London cast of Hair. With comprehensive listings of over 500 related features, documentaries, TV programmes and shorts, an unforgettable trip through the swinging 60s.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 354

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in 2016 by

Oldcastle Books Ltd,

PO Box 394, Harpenden,

AL5 1XJ, UK

oldcastlebooks.co.uk

@PsychedelicCel

© Simon Matthews, 2016

The right of Simon Matthews to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of the publishers.

Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN

978-1-84344-457-2 (Print)

978-1-84344-458-9 (Epub)

978-1-84344-459-6 (Kindle)

978-1-84344-460-2 (Pdf)

For

Candy and a Currant Bun

Contents

Introduction

Set the Controls for the Heart of W1

1965

The Knack

Help!

After Oklahoma…

1966

Alfie

Modesty Blaise

The Game is Over (La Curée)

Georgy Girl

In the Land of the Auteurs

Charlie is my Darling

Mick and the Droogs?

Blow-Up

The Family Way

1967

Anna

Just Like a Woman

Privilege

La Collectionneuse

Mord und Totschlag (A Degree of Murder)

Jeu de Massacre

Barry, Reed and Bown

The Jokers

Smashing Time

Whatever Happened to the Battersea Bardot?

Poor Cow

How I Won the War

To Sir, With Love

The Mini Affair

Tonite Let’s All Make Love in London

Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush

Bedazzled

Magical Mystery Tour

Popdown

1968

Separation

Mrs Brown, You’ve Got a Lovely Daughter

30 is a Dangerous Age, Cynthia

Up the Junction

Nerosubianco

The Swinging London

Renaissance Man

Only When I Larf

Wonderwall

Det Var En Lørdag Aften

Work Is a Four Letter Word

Yellow Submarine

Sette volte Sette

Baby Love

The Committee

The Bliss of Mrs Blossom

Better a Widow (Meglio Vedova)

The Girl on a Motorcycle

Otley

Sympathy for the Devil (One Plus One)

The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus

The Touchables

Joanna

1969

The Virgin Soldiers

The Guru

What’s Good for the Goose

The Tilsley Connection

If It’s Tuesday This Must Be Belgium

The Reckoning

Supershow

The Haunted House of Horror

More

Paroxismus

The Stones in the Park

Moon Zero Two

Pensiero D’Amore

The Magic Christian

All the Right Noises

Till Death Us Do Part

Kenny Lynch

1970

Scream and Scream Again

Take a Girl Like You

The Breaking of Bumbo

The Name’s Connery, Neil Connery…

Connecting Rooms

Let It Be

Cannabis (French Intrigue)

Exquisite Thing…

Loot

Twinky

Groupie Girl

Amougies (Music Power and European Music Revolution)

Eyewitness

Goodbye Gemini

This, That and The Other!

Entertaining Mr Sloane

Alba Pagana (May Morning)

The Beast in the Cellar

Bronco Bullfrog

Leo the Last

Deep End

Performance

Daddy, Darling

Groupies

The Body

Gimme Shelter

The Ballad of Tam Lin

Cucumber Castle

There’s a Girl in My Soup

Be Glad for the Song Has No Ending

1971

Hurray! We’re Bachelors Again

Percy

Girl Stroke Boy

Friends

Bread

Melody (S.W.A.L.K.)

Not Tonight, Darling

Extremes

Universal Soldier

Phun City: The Best Concert Film You’ll Never See?

Beware of a Holy Whore

How Hair! Made Oscar a Star…

Private Road

Hammer: The Pop Years

The Tragedy of Macbeth

Love and Music (Stamping Ground)

A Clockwork Orange

Fata Morgana

1972

Permissive

Christa

Continental Circus

The Four Dimensions of Greta

Glastonbury Fayre

La Vallée

Gold

Made

The Alf Garnett Saga

The Pink Floyd, Live at Pompeii

Dracula AD 1972

Death Line

Born To Boogie

1973

Psychomania

O Lucky Man!

That’ll Be the Day

The Final Programme

The Wicker Man

The Connoisseurs Guide to 60s Pop Film Music…

1974

Zardoz

Jodorowsky

Stardust

Son of Dracula (Count Downe)

Little Malcolm And His Struggle Against The Eunuchs

APPENDICES

1. Other Feature Films

2. Documentaries and Concert Films

3. Shorts

4. TV Musical Specials, Documentaries, Concerts

5. TV Dramas

Afterword

Index

INTRODUCTION

In his seminal study of the genesis, birth and flowering of UK pop culture, George Melly called it a ‘revolt into style’: the moment the UK collectively burst out of the monochrome cocoon of the 50s and into the dazzling colours, designs and optimism of the 60s. The rapidity of the change is something which – in itself – confirmed to Melly and other observers that, due to its transience, this was a truly ‘pop’ event. The enormous difference in style and approach between the two eras, concertinaed into just a few years, is best illustrated by watching two films directed by Michael Winner: West 11 and The Jokers.

A key early success for Michael Winner

The former, made in black and white and set in a dingy room in the then slum district of Notting Hill Gate (thus making it a companion piece to The L-Shaped Room), is resolutely ‘kitchen sink’, perhaps hardly surprising given that its script came from the pen of Keith Waterhouse, whose other cinema credits at this point included Whistle Down the Wind, A Kind of Loving and Billy Liar. West 11 is bleak. Dismal street scenes where gangs of children kick balls along canyons of ill-kept tall Victorian houses, pockmarked by bomb sites, unworried by traffic; the cast and extras wear nondescript clothes with no immediate or discernible style and eat hurried little meals in basic street corner cafes. The central character, played by Alfred Lynch, who after this rare leading role was seen mainly on TV, seeks solace in popping pills, rejects Roman Catholicism (shades here of Graham Greene) and hangs out at the local jazz club; a cramped basement, this features apparently unamplified performances from Ken Colyer’s Jazzmen and the Tony Kinsey Quartet. The former, respected and fiercely inscrutable pioneers of the UK ‘trad’ scene, the latter an offshoot of the Johnny Dankworth Seven, playing cool hard bop with a UK rather than a US tinge. The audience dances politely, jives (slightly), drinks coffee and orange juice or sits out numbers on the floors leaning back against the cellar wall such is the lack of furniture. Diana Dors cruises around, hoping to pick up a man, much as she did in Dance Hall (50). West 11, which came with a marvellously evocative title theme from Acker Bilk - quite the

best thing he recorded and now very hard to come by - was filmed in the spring of 63, some six months after That Was the Week That Was had begun knocking holes in the reputation of Harold Macmillan and was released at the point the Profumo scandal ushered in the brief era of Sir Alec Douglas-Home. Although The Beatles had already secured their first US number one with ‘She Loves You’, at the point West 11 appeared it still looks like the England of rationing, shortages and national service.

Just three years later, Winner was directing The Jokers… resolutely undingy… and featuring Oliver Reed (ascending to stardom via this film) and Michael Crawford, midway between his roles in The Knack and How I Won the War, skidding around the posh bits of London in a Mini Moke and narrowly avoiding the band of the Grenadier Guards en route to the Trooping of the Colour. Reed and Crawford spend much of their time at night clubs or society parties (during which the film includes split second appearances from two as yet unidentified pop groups of the era) before they career off to the strains of the Peter and Gordon title theme to rob the Tower of London. The film is in colour. The cast is mainly young. They wear the latest clothes. The interiors look like the 60s rather than the 20s. The script jettisons the social realism of West 11 and is amiable, contemporary, flip and paced like a situation comedy. The Jokers is clearly a pop film of the sort that would have been unthinkable a few years earlier… when pop music itself, before the sudden appearance of the pirate radio stations in 64, was confined in the UK to a mere five hours air time per week.

The best selling pop film of 1964 – and did better business in the US than Elvis Presley’s Viva Las Vegas

In his narrative, Melly, perhaps hardly surprisingly given his own Liverpudlian origins, identifies The Beatles as the key drivers of this change and punctuates his account with regular bulletins about their progress through the decade. The case for British pop cinema beginning – and ending – with The Beatles is indeed strong. Although there had been earlier pop films, and both Tommy Steele and Cliff Richard had reached film star status (in the UK domestic market, if nowhere else), neither the films nor their major players had a significant global impact, nor did their style permeate society as a whole. The huge success of A Hard Day’s Night – the ninth biggest grossing film in America in 64 – was the single event that brought serious US studio money to London and kickstarted the whole genre. Shot in early 64 and released in July that year, A Hard Day’s Night may have cemented The Beatles’ success

and brought dollars flooding into the UK. But is it a typical Swinging London film? Despite boasting sequences shot in John Aspinall’s W1 casino Les Ambassadeurs (one of the rarefied trend-setting pinnacles around which much of what followed would revolve), it much more closely resembles the preceding genre of ‘kitchen sink’ dramas. The characters emerge from the North of England. It is shot in black and white. The script is by Alun Owen, whose previous credits included many working class social realist TV dramas and the screenplay for the crime thriller The Criminal; the supporting cast includes Norman Rossington, previously seen in Saturday Night and Sunday Morning and the incomparable Wilfred Brambell, moonlighting here from his grotesque duties in Steptoe and Son. Its key difference was that it dropped the usual downbeat, grimy, approach of its predecessors and offered its audience instead an optimistic, zestful and youth-orientated narrative. These ingredients owed much to its director, Richard Lester, an astute choice for the gig. A child prodigy from Philadelphia, resident in the UK since the early 50s, Lester first came to attention directing the 61 pop film It’s Trad Dad, which, despite a hackneyed putting-on-a-show plot, was interspersed with superbly designed and shot musical interludes that predated music videos by two decades. He followed this with the Cold War/space race satire The Mouse on The Moon, which surprised many by being a modest success on the US college and campus circuit. Importantly, Lester had Goon connections too. With Lennon, in particular, holding the madcap surrealism of Milligan and Sellers in high regard, Lester’s work on the TV series A Show Called Fred in the mid 50s and his award winning short The Running Jumping and Standing Still Film (59) commended him further. Stylistically A Hard Day’s Night and the productions that flooded on to the cinema screens of Britain from 65 onwards also owed much to selected European cinema releases of just a few years earlier: the high fashion and seemingly improvised plot of La Dolce Vita, the freewheeling youthfulness of Jules et Jim, the classic young-people-in-a city storyline of Bonjour Tristesse and the elegant combination of sexuality and music in Una Ragazza Nuda/Strip-Tease (starring Nico with songs by Serge Gainsbourg). All are quite unlike the diet of war films, Rattiganesque drawing-room dramas and eccentric comedies that prevailed in the UK for many years after 45. The case for Richard Lester being the key auteur of the UK pop film of the 60s and 70s is strong indeed and it is ironic that the discarding of this baggage, and its replacement by films in which music, graphic design and inventive title

sequences predominated, owed a great deal to two external influences – a US director (Lester – whose first major success brought in US money) and European art house cinema.

Scene through the eye of a lens: Richard

Lester, auteur of the Swinging London genre

Flushed with the success of A Hard Day’s Night Lester moved quickly on to his next two projects. These appeared within a few weeks of each other in 65 and really did establish the UK pop film genre: an adaptation of the Ann Jellicoe play The Knack and Help!, a sequel for The Beatles. The former was an immaculate blend of dialogue, visual imagery, music and fashion that was so striking in its tone that at least one critic described himself as leaving the cinema in a state of euphoria after seeing it. The latter placed The Beatles at the centre of an absurd chase/caper plot – which would have suited Buster Keaton fifty years earlier – and had them performing a dozen songs in various costumes and locations. Slightly less successful than A Hard Day’s Night, it nevertheless inspired many imitations as well as the massively popular TV series starring The Monkees. It was, predictably, an enormous US success.

The big Hollywood studios now unveiled popular entertainments like Alfie, Georgy Girl and Modesty Blaise as well as Blow-Up, MGM’s venture into the serious ultra-stylish European art house market. During the course of 66, all of these outstripped Help! at the box office, whilst in 67 To Sir, With Love did better business than all of them, and remains the biggest grossing example of the type even today. The latish spin-off from the early 60s satire boom, Bedazzled, from 20th Century Fox, did well too. Such was the appetite for anything English that big US studios were happy to distribute virtually any film with a pop – or youth – angle, thus ensuring that finance could be raised for productions like The Jokers, How I Won the War (Lester again), Smashing Time, Up the Junction and Only When I Larf. Nor was the boom restricted to major UK and US film producers. Would-be independent auteurs flocked to London from many parts of the world, hoping for a slice of the action, discovering in the process that London was easy to film in, there were few permits or taxes that needed to be paid and professional domestic film crews were easily available. Both The Mini-Affair and Popdown were made by US independent film makers hoping to make a killing, whilst the mega-success of Blow-Up resulted, in time, in several European directors shooting in London and carefully incorporating – somewhere in their plot – the latest group or singer in either acting or musical roles. The launch in

late 67, by The Beatles, of their Apple boutique in Baker Street W1 (which duly appears in the film Hot Millions) seems emblematic of this first flourish of activity: a major happening combining music, fashion and design. But, again, it’s worth remembering that the striking mural on the side of the building (setting it aside from its rather dowdy neighbours) was designed by the Dutch design collective The Fool, which a year later would bring out their own folkrock LP, another rather ironic instance of how much of Swinging London came from abroad. Opening a hip clothes shop was not, as it transpired, the limit of The Beatles’ ambitions. In the summer of 67 they established Apple Films, to produce their BBC TV Special Magical Mystery Tour. The intention was that this would be the first of a series of pioneering and artistically adventurous credits from a new youth-orientated UK studio. The feature length cartoon Yellow Submarine and the psychedelic mood piece Wonderwall duly appeared as the earliest, and possibly the best, examples of its work.

The Apple boutique during its brief flowering on an otherwise dowdy London street corner

The US-funded boom in British films continued through 68 and 69 – despite Swinging London then beginning to recede somewhat – with productions such as Mrs Brown, You’ve Got a Lovely Daughter, Otley, The Bliss of Mrs Blossom, The Guru and If It’s Tuesday, This Must Be Belgium, the latter a major box office success. It even extended, remarkably perhaps, into explicitly UK dramas such as The Virgin Soldiers and The Reckoning. Some commentators wondered at the continued US preference for anything London – but films often take a long time to shoot, edit, dub and complete and money committed in 66-67 was still trickling through the system some years later. European finance was also significant during this period, whether being spent in London itself (Nerosubianco and Sympathy for the Devil) or elsewhere (The Girl on a Motorcycle). The phenomenon peaked in 69-70 when, bolstered by the apparent certainty of lucrative US distribution deals, UK filmmakers produced a crop of inventive releases including The Magic Christian, Take a Girl Like You, The Breaking of Bumbo (all adapted from novels), Loot, Connecting Rooms and Entertaining Mr Sloane (all plays) and completely original projects such as Joanna, The Touchables, Leo the Last and Performance. Most of these boasted a resident group or a singer in an acting role and had a strong eye on the burgeoning soundtrack LP market. A plethora of European art house releases also appeared at the same time, mining much the same seam – More, Paroxismus, Deep End, Cannabis and Alba pagana. Indeed,

by the end of the decade, the pop film style had seeped everywhere: into horror with The Haunted House of Horror, into sci-fi with Moon Zero Two and into comedy via What’s Good for the Goose. The last, an attempt to ingratiate himself with the youth market by veteran comedian Norman Wisdom, was not dissimilar to a number of dramas that appeared in the aftermath of the September 68 relaxation of censorship in the UK. Most had plots centred on the age of consent (All the Right Noises, Twinky) and generally featured middle aged men enjoying relationships with sexually available younger girls. It was a trend that, whatever its reasonably stylish and legitimate origins, spiralled down quickly into the tackiness of the 70s UK sex film.

Picking a moment when the canon peaked, one would surely settle on 70. By that point, two additional sub-genres had appeared, expanding the broader parameters of the pop film and reflecting the increased independence and spending power of youth compared to previous generations. The first of these was the concert movie, usually a sprawling semi-improvised documentary about a particular event (Supershow, Amougies, Love and Music and Glastonbury Fayre). Ironically, this had been pioneered in the UK with Charlie is my Darling, the 66 Rolling Stones film that never made it into the cinemas and later, on a modest scale, by DA Pennebaker’s Don’t Look Back; but only really took off after the massive US success of Monterey Pop (also Pennebaker) in the summer of 68. The second was the emergence of the serious experimental art film, decked out with progressive music, shown at film societies and in student unions on the ever expanding network of universities and polytechnics, at late night showings in Odeons, Gaumonts and ABCs and in the nascent independent cinemas: The Body and Continental Circus come to mind, as do early works by Werner Herzog and Rainer Werner Fassbinder.

DA Pennebaker zooms in on Dylan during his 1965 UK tour

1970 also saw the filming of A Clockwork Orange, which yielded the biggest selling pop soundtrack LP of the era and Get Carter. Both were astonishingly successful at the box office, only to be dogged by misfortune. The former was pulled from the distribution circuit after public demonstrations against its extreme sex and violence, whilst the latter, despite topping the US viewing charts for three weeks between Love Story and Summer of ‘42 – remarkable for such an impenetrably British film – quickly disappeared from sight. There would be no sequels, and Get Carter did not inaugurate a UK equivalent of

the French genre of realistic and creative crime dramas. In reality, something so dependent on US money and distribution deals couldn’t last and, once all the major US studios posted losses at the end of the 60s, the funding of ventures in London quickly dried up. Apart from purely internal Hollywood problems it can hardly have helped – in the perception that studio bosses had about the marketability of pop films – that The Beatles broke up in 70 (as did Herman’s Hermits and The Dave Clark Five, the two other most significant UK pop groups in terms of sales in the US in the mid and late 60s) and The Rolling Stones moved into tax exile not long after. The suddenness of the change is best illustrated by Terence Stamp who, when interviewed in 2013 (doing publicity for his role in Song for Marion), drily commented ‘… when the 60s ended, so did I…’ If one of the greatest faces of the era, internationally acclaimed after roles in Modesty Blaise, Far from the Madding Crowd and Poor Cow and a string of elegant European ventures such as Blue, Theorem and The Mind of Mr Soames, couldn’t command a single decent leading role, what hope was there for other stars created in such a fragile boom? With the exception of Michael Caine and Oliver Reed, very little it would seem. Rita Tushingham experienced a major career gap after 69, David Warner did little post 70, David Hemmings left for an abortive trip to Hollywood in 71 and Hywel Bennett spent more time in TV than film from 72. All had been major box office draws just a few years earlier and all had disappeared from sight by 73.

By the mid 70s, the UK film industry was in low gear. Although EMI remained active, there was less money around, less willingness to invest (even modestly) in original ideas or experimentation and a tendency, instead, to rely on reliable formulas, preferably with a nostalgic bent. For every Wicker Man or Zardoz there were innumerable TV adaptations. Hemdale, the major UK hope of only a few years earlier, faded away after producing Connecting Rooms, Melody and Boy Stroke Girl, none of which was a hit, and distributing the mega-flop Universal Soldier. The continuing reduction in cinemas and rise in TV ownership were also factors. Although the overall numbers of productions did not decline catastrophically, the figures tended to be bulked out by US (or foreign) films shot in UK studios. In terms of purely domestic product it would be fair to say that, by 73-74, it consisted of an annual Bond, a Carry On and a couple of Hammers, all graced by increasingly elderly casts, TV spin-offs, annual additions to the Adventures of and

Confessions of sex comedy series, and below that, a slew of adult only sex films – most now long forgotten – of almost no merit. Pop groups and pop singers in acting roles tended not to be seen at all. In the end, Apple, even Apple, underpinned by the riches of The Beatles, ended film production in 74 after releasing its last two productions Son of Dracula and Little Malcolm and His Struggle Against the Eunuchs, both of which had started shooting a couple of years earlier. They made almost zero impact when released and this effectively brought the era of the UK pop film to a close… a rather sad fizzling out of what had briefly seemed an era of limitless possibilities.

A few films with pop music did continue to appear, of course, but they were no longer representative of UK productions as a whole. Tommy (75), Ken Russell’s multi-star extravaganza, did well in the US and duly spawned Quadrophenia, which was filmed in 78 and premiered at Cannes in 79. The problem was: Tommy, with its enormous cast and big production values, was rather like a rock musical version of It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad World or Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines, whilst Quadrophenia, when it appeared, was already anachronistic in much the same way That’ll Be the Day and Stardust had been a few years earlier. The relative success (but only in the UK) of Quadrophenia was followed by Breaking Glass with its traditional glum rags to riches/road to ruin plot and The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle, a deliberate, and entertaining, pastiche (by Malcolm McLaren) of much earlier productions like The Tommy Steele Story and Expresso Bongo in a provocative style that owed more than a little to Serge Gainsbourg. Unlike Gainsbourg, though, McLaren did not go on to have a major career in film.

Thereafter, things were bleak indeed. Although George Harrison returned – with Handmade Films – to produce Life of Brian in 78-79 after EMI had pulled out, and followed this with The Long Good Friday and Time Bandits, anything to do with the contemporary British pop scene was conspicuous by its absence on screen. The major groups and singers of the 80s and 90s were not automatically drafted in to spy thrillers, offered major acting roles or casually seen in obligatory discotheque scenes. Nor were they the immediate choice for composing or performing film themes. Homage to the genre was a long time arriving, and when it finally did, came – as so much had between 65 and 74 – from the US. Austin Powers : International

Man of Mystery (97) appeared shortly after the first flowering of ‘Brit Pop’, whose major exponents Blur, The Verve, Suede, Oasis, Pulp and Elastica pillaged heavily from the musical legacy of the 60s and 70s with many – dozens, actually – of referential borrowings from and tributes to the UK pop films of the period. It is interesting, perhaps, to speculate that Austin Powers, which began shooting in 96, was seen as a commercially attractive project in Hollywood after the success in the US of Suede and Oasis. It starred a gormless central figure (apparently channelling the late Simon Dee) rigged out à la George Lazenby in his sole Bond outing in 69 in a blue velvet suit and ruffed shirt, who duly crashes through a variety of ludicrous encounters as a secret agent. Michael York co-starred – selected partly on the basis of his (much) earlier roles in films like Smashing Time and The Guru – and it even came with a contribution on its soundtrack by The Mike Flowers Pops (whose major hit during this period was an immaculately tongue-in-cheek lounge version of the Oasis song ‘Wonderwall’, whose title, of course, was culled from the 68 film), parodying the easy listening themes of Burt Bacharach. Austin Powers was sufficiently successful to spawn two sequels, which were enormous box office hits in 99 and 02 respectively. Thereafter, British cinema also caught up with its predecessors, producing a number of elegant and well made dramas of which Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels (98) and Layer Cake (04) were the most notable. The former borrowed heavily from the semi-comic crime capers of the 60s whilst the latter owed much to gritty realistic films like Get Carter. Like Austin Powers, both were noted for their soundtrack LPs, substantial artefacts in their own right, which mixed a wide variety of material culled from the present and past; something the films of the 60s and 70s would not have done, concentrating as they mainly did on completely contemporary music.

The ultimate homage to the world of late

‘60’s early ‘70’s UK feature films, albeit

played as parody, and created by Mike

Myers – a Canadian long resident in London

The narrative here could continue … but now is the time to look, one by one, at what makes up the mother lode. Selecting the films required defining – somehow – what should and should not be considered a UK Pop film. It seemed common sense that the definition should embrace any film featuring a UK pop singer (or group) of the period in acting roles, or appearing in a specific scene or credited on the soundtrack, usually, if in the latter capacity, performing the title song or theme. Beyond that, anything with a specifically ‘youth’ angle in terms of cast, plot, design or appeal seemed appropriate. Inevitably, though, even these parameters produced anomalies. What about the Bond

films? Although raided extensively for the Austin Powers franchise, and with some iconic music, Bond himself was hardly a child of the 60s: a fortyish leading man, who’d served in the war, he was clearly designed to appeal to adults. Putting 007 to one side, therefore, and starting with The Knack and Help! made sense, and treating A Hard Day’s Night, Darling and Morgan – A Suitable Case for Treatment as late examples of the preceding period justified. Over three hundred productions emerged, some from the fog of history, some hardly seen since their release (if indeed they were ever released), and are collected here in chronological order, irrespective of whether they are film or TV productions or whether they are UK or European in origin. As this book covers British pop, purely US films are generally excluded, though a few that featured British singers and bands did creep in to the listings. The appendices provide listings of features of lesser significance, shorts, documentaries and TV dramas… anything, in fact, that might seem relevant to the topic. Excluded are Top of the Pops, Ready, Steady Go! and many other UK TV series that ran for years on end and specifically featured the latest pop acts: compiling a listing of these was impossible (many episodes now being wiped) and this book is not an attempt to catalogue them. Travelling through the period and assembling images and an accompanying text yielded some strange facts. Who could identify which UK group appeared in, or contributed to, the highest number of film and TV ventures during this period? Neither The Beatles nor The Rolling Stones gained this accolade. The most prominent performers in front of the cameras between 65 and 74 turned out to be Pink Floyd, who worked on eight features and two shorts, appeared in a major Belgian TV special, can be heard on the soundtrack of two other features and might have had something to do with the Spanish film Salome (if anyone ever finds a copy and manages to investigate). They even had time to turn down A Clockwork Orange. Critics may yet speculate how much their musical development away from quirky psych-pop to the long tonal pieces that eventually made them the biggest band in the world in the mid 70s might have been down to the influence of composing music for films…

Now read on!

Set the Controls for the Heart of W1!

Not everyone would turn down the chance to work with Stanley Kubrick but the inability of Pink Floyd to agree terms about the use of ‘Atom Heart Mother’ in A Clockwork Orange – although a faux pas in subsequently denying them royalties from an astonishingly successful soundtrack LP – simply wasn’t that critical, for them, in terms of their career development.

Dubbed ‘the light kings of England’ by their US label Tower, their screen credits between 66 and 72 were prodigious: the Peter Whitehead short London 66-67, later expanded into the documentary feature Tonite Let’s All Make Love in London, a promo-film for their debut single ‘Arnold Layne’, live concert footage in Dope (co-produced by DA Pennebaker, but rarely if ever seen), a slot in the Belgian pop TV film Vibrato, an album’s worth of unreleased music for The Committee, live footage in the US documentary short San Francisco, an extract of ‘Interstellar Overdrive’ used in The Touchables, the soundtrack for More, another soundtrack, mostly unreleased, for Zabriskie Point, background music for the documentary feature The Body, appearances in two of the post-Monterey Pop concert films of the period, Amougies and Stamping Ground and the soundtrack for La Vallée. Other curiosities include the Spanish feature Salome (70) which claims to include on its soundtrack a rearrangement, by Jorge Pi (of the Bilbao Blues Band), of the Pink Floyd arrangement of ‘Salome’ by Richard Strauss and the use of their material in two Kung Fu films: Fist of Fury (71) and Intimate Confessions of a Chinese Courtesan (72).

Given that the group started out sharing a house with Mike Leonard, an architect who devised and built optical effects for use on stage and film, went on to use specially commissioned light shows by Peter Wynne-Willson and whose original lead guitarist Syd Barrett lived with pop artist Duggie Fields, with hindsight it’s hardly surprising that they spent almost as much of their time composing film music or appearing in front of the cameras as they did on tour and recording.

THE KNACK

Richard Lester directs Michael Crawford and Rita Tushingham star

A Richard Lester adaptation of an Ann Jellicoe play, originally performed at the Royal Court Theatre in 1962, The Knack stars Rita Tushingham – an absolutely iconic female star of the period after roles in A Taste of Honey, Girl with the Green Eyes and The Leather Boys – as a young, single woman arriving by train in London who ends up sharing a house with Ray Brooks (an immaculately dressed, very hip and predatory musician), Michael Crawford (a sex-starved teacher) and Donal Donnelly (an eccentric artist).

Beautifully made and the epitome of cool, Swinging London, the film projects an optimistic feeling that almost anything might be possible and is brilliantly shot in the style of Lester’s previous mega-success A Hard Day’s Night. Unlike preceding dramas in which anyone under 30 was, at best, just a supporting figure in a larger cast, The Knack – in which Crawford and Tushingham explore newly available sexual freedoms and clumsily try to get ‘the knack’ of successfully establishing relationships with the opposite sex – is almost entirely orientated towards young people. The Knack thus makes a good claim to be considered the first feature film to adopt this typically 60’s youth centric approach to its storyline whilst still being firmly targeted at the wider adult audience. Hugely liked at the time, it won the Palme d’Or at Cannes.

Rita Tushingham reads about Paul Klee

The very jazzy soundtrack was by John Barry, with contributions from Alan Haven and Johnny de Little (formerly vocalist in The John Barry Seven). Haven was an ideal choice – a jazz organist married to the then Miss World who had simultaneously composed and released ‘Image’ the popular instrumental used as a theme by Radio Caroline.

Released 3 June 1965, 85 minutes, black and white

DVD: released by Twentieth Century Fox, August 2004

SOUNDTRACK: released on United Artists in 1965.

Reissued on Simply Vinyl in 2001

HELP!

Richard Lester directs The Beatles star

For the second Beatles picture Richard Lester was given a significantly bigger budget than that available for A Hard Day’s Night. This allowed him to film in colour and to base some parts of the plot abroad: the sections in Help! set in a ski resort and the Bahamas duly followed. Shot by Lester almost simultaneously with his work on The Knack, the script was written by US novelist Marc Behm (whose previous credit was the Cary Grant-Audrey Hepburn thriller Charade) and UK playwright Charles Wood. This replaces the semi-documentary approach of A Hard Day’s Night with a surreal comedy-caper about an Indian cult chasing Ringo (not dissimilar in style to Lester’s previous credit Mouse on The Moon) interspersed with carefully set and choreographed songs, each resembling a music video – a format Lester had earlier used in It’s Trad Dad (1961). Leo McKern, Eleanor Bron and Victor Spinetti co-star, the last something of a fixture in The Beatles entourage at this point.

The Beatles on Salisbury Plain

An immense success at the box office, the film was noted for the high levels of cannabis consumed by The Beatles during its production. The end result resembles (and is arguably no better than) any single episode of the 50’s BBC radio series The Goons (with whom, of course, both George Martin and Richard Lester had worked) expanded here with the newly available funds to an indulgent length. The sequences, often loosely related to the storyline, of The Beatles performing in various costumes and settings quickly became the de rigueur template for most pop group films, being copied with great success by The Monkees et al.

The accompanying LP – which doubled as a soundtrack in the UK – was released in August 65 and reached no. 1 in virtually every territory.

Released 29 July 1965, 92 minutes, colour

DVD: released by Parlophone Records, November 2007

SOUNDTRACK: UK LP released 6 August 1965 contains solely material performed

by The Beatles. US release (13 August 1965) includes tracks from George Martin

and Ken Thorne and is billed as ‘Original Motion Picture Soundtrack’

After Oklahoma…

From its appearance in the early ‘50’s, the LP was closely associated with original soundtrack or original cast recordings of film and stage musicals: Oklahoma, South Pacific, The King and I, Gigi and West Side Story were the mega successes of their time with chart runs of up to 20 years, easily eclipsing anything produced by other genres. The desire by the wider public for a vinyl artefact with sing-along show tunes and brooding theme music continued after the emergence of The Beatles: Mary Poppins, My Fair Lady, The Sound of Music, Dr Zhivago, Oliver and Paint Your Wagon all sold in numbers most groups and singers could have only dreamt about. Only Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey came close to matching this.

The May 67 success of Blow-Up, with its brief placement in the lower regions of the US Top 200, was remarkable therefore – the more so because it was written and performed by Herbie Hancock, keyboards player in the Miles Davis Quintet, supported by several fellow jazzers. UK group The Yardbirds appeared on one track. A few months later To Sir, With Love became the first pop film to produce a major US chart LP, starting something of a minor trend there in 68-69 when Wild in the Streets (Max Frost and The Troopers), Candy (The Byrds, Steppenwolf) and Easy Rider (The Byrds, Steppenwolf, Jimi Hendrix) all sold well as a younger audience emulated their parents and bought mementos of a great night out at the cinema. In the UK The Pink Floyd were the only group to create complete soundtracks and enjoy significant commercial success with More and Obscured by Clouds; whilst the sprawling triple LP released to accompany the US concert movie Woodstock also sold well, as did the compilation double LP issued for That’ll Be the Day. By far the greatest success, though, for a pop or counter-culture film soundtrack during this period was A Clockwork Orange with its mixture of original classical, classical rescored for synthesizer and psychedelic folk.

During its peak the British pop film may have only produced a half dozen or so commercial soundtrack successes, but dozens of superb songs and hundreds of pieces of brilliant music were littered across the genre, to be disinterred, re-issued and sampled by the musical archaeologists in the decades that followed.

ALFIE

Lewis Gilbert directs Michael Caine stars

Michael Caine and co-stars

Independently produced and directed by Lewis Gilbert, whose best known previous credits included some of the most iconic UK war films of the 50s and early 60s, from a not particularly well known 63 Bill Naughton play, Alfie was not initially seen as obvious box office and had a troubled genesis. Prior to being accepted by Michael Caine, the lead role was turned down by Laurence Harvey, Anthony Newley and Terence Stamp, the budget was not overly generous and Shelley Winters had to be added as a co-star to ensure a US release. Strong supporting parts were played by Millicent Martin and Julia Foster. Martin had been a mainstay

of the TV satire show That Was the Week That Was whilst Foster had accrued an impressive set of credits: co-starring with Michael Crawford in Two Left Feet (where with hindsight his character of the hapless virginal young man was very much his dummy run for The Knack), with Anthony Newley in the Soho based drama The Small World of Sammy Lee, fitting in an acclaimed slot in NF Simpson’s absurdist hit play One Way Pendulum and with Oliver Reed in Michael Winner’s The System. Also featured was Jane Asher, a child star in the 50s who was, by this point, dating Paul McCartney.

The plot concerns the sexual adventures of an amoral young(ish) cockney Lothario (Caine) who – eventually – gets his comeuppance. Filmed almost entirely in and around London, it cost only 0,000 (£170,000) to make and was staggeringly successful, becoming the then biggest UK film ever in the US, and receiving 5 Academy Award nominations. Over the next few years, this duly resulted in many US studio-financed features being filmed in London whose storylines shared broadly similar parameters (tourist views of the capital + young cast + music + Swinging plot) in the anticipation that they would produce similar commercial returns. The central character proved to be so popular (the eternal single bloke, playing the field and getting into continual sexual escapades) that the film eventually produced Alfie Darling, a 76 sequel starring pop singer Alan Price.

The soundtrack was by jazz saxophonist Sonny Rollins and contained a Bacharach-David theme song that swiftly became one of the most widely heard and covered songs of the era. The UK recording, by Cilla Black, reached number nine when released in March 66 and was followed by US versions by Cher (number thirty two, August 66) and Dionne Warwick (number fifteen, May 67).

Released 29 March 1966, 114 minutes, colour

DVD: released by Paramount Home Entertainment, August 2002

SOUNDTRACK: LP released in UK on Impulse in 1966. Re-issued on CD in 1997

MODESTY BLAISE

Joseph Losey directs Monica Vitti and Terence Stamp star