18,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

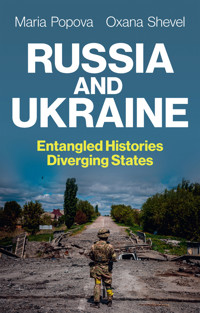

In February 2022, Russian missiles rained on Ukrainian cities, and tanks rolled towards Kyiv to end Ukrainian independent statehood. President Zelensky declined a Western evacuation offer and Ukrainians rallied to defend their country. What are the roots of this war, which has upended the international legal order and brought back the spectre of nuclear escalation? How did these supposedly “brotherly peoples” become each other’s worst nightmare?

In Russia and Ukraine: Entangled Histories, Diverging States, Maria Popova and Oxana Shevel explain how since 1991 Russia and Ukraine diverged politically, ending up on a collision course. Russia slid back into authoritarianism and imperialism, while Ukraine consolidated a competitive political system and pro-European identity. As Ukraine built a democratic nation-state, Russia refused to accept it and came to see it as an “anti-Russia” project. After political and economic pressure proved ineffective, and even counterproductive, Putin went to war to force Ukraine back into the fold of the “Russian world.” Ukraine resisted, determined to pursue European integration as a sovereign state. These irreconcilable goals, rather than geopolitical wrangling between Russia and the West over NATO expansion, are – the authors argue – essential to understanding Russia’s war on Ukraine.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 553

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Dedication

Title Page

Copyright Page

Abbreviations

Illustrations

Tables

Figures

Maps

Acknowledgments

Introduction: Russia’s invasion and Ukraine’s resistance

The root of the war: Russian re-imperialization vs. Ukrainian independence

Was the 2022 war inevitable?

Could the West have prevented the war?

Book outline

Notes

1 Entangled histories and identity debates

Entangled histories

From Kyivan Rus’ through tsarism

The turbulent twentieth century

A new page in the Russo-Ukrainian relationship

Competing visions of the Russian nation

Identity politics and imperialization

Competing visions of the Ukrainian nation

Identity politics and commitment to independence

Public opinion and Ukrainian identity

Notes

2 Regime divergence

Presidents vs. parliaments amid economic crisis

New constitutions and crony capitalism

Competitive authoritarianism’s end (one way or another)

The Orange-era divergence

Last chance for regime convergence

Was regime divergence inevitable and would regime similarity have made war less likely?

Notes

3 Historical memory, language, and citizenship

History and memory

Holodomor

The OUN and the UPA

Citizenship policy

Language policy

Notes

4 Ukraine, Russia, and the West

The collapse of the USSR

Defining the Russo-Ukrainian relationship

Orange is the worst color

Yanukovych, Russia’s last hope

Could the West have prevented the collision course?

Notes

5 Euromaidan, Crimea annexation, and the war in Donbas

Euromaidan (The Revolution of Dignity)

The EU association agreement: a geopolitical fork in the road

Protests begin: November 2013

Inconsistent repression, insufficient accommodation: December 1 – January 16

Repression, radicalization, and violence: January 16 – February 20

Regime collapse and the Yanukovych ouster: February 20–22

The aftermath of Yanukovych’s ouster

The southeast and separatism before Euromaidan

The southeast and Euromaidan

Crimea’s takeover, “referendum,” and annexation

Donbas conflict starts

The Minsk Agreements: Russia’s Trojan horse for Ukraine

Notes

6 The road to full-scale invasion

Electoral geography changes in post-Euromaidan Ukraine

Accelerating policy divergence

Deepening Ukrainization

Decommunization

Religion

Language

Building Ukrainian democracy better

Judicial reform

Anti-corruption reform

Decentralization reform

Ukrainian democracy and Russian aggression

Moving toward Europe

Russia comes to see Ukraine as the “anti-Russia”

Imperialization of identity in Russia

Krym Nash and Russian autocratization

The collision course

Minsk peace process failed

Military buildup and last-ditch diplomacy

Notes

Conclusion

Ukraine: state and society resilience

Russia: genocidal dictatorship?

Where do we go from here?

Ukraine: European, democratic, no longer “post-Soviet”

Post-war Russia: global re-integration will take more than Putin’s departure

Lessons for the West

Notes

References

Index

End User License Agreement

List of Tables

Chapter 1

Table 1.1 December 1991 independence referendum vote in Ukraine, and ethnic Russians and R...

List of Illustrations

Chapter 1

Map 2.1

Regions where pro-Western parties won the party list vote in parliamentary elect...

Chapter 2

Figure 2.1

Political regime divergence in Russia and Ukraine

Chapter 4

Map 4.1

Waves of EU enlargement

Map 4.2

Waves of NATO enlargement

Conclusion

Figure 7.1a

Support for EU membership in Ukraine (%)

Figure 7.1b

Support for NATO membership in Ukraine (%)

Figure 7.2

Growth of Ukrainian civic identity

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

ii

iii

iv

vi

vii

viii

ix

x

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

Dedication

To all Ukrainian children kidnapped by Russia.

May they come home soon to their families in free Ukraine.

Russia and Ukraine

Entangled Histories, Diverging States

Maria Popova

and

Oxana Shevel

polity

Copyright Page

Copyright © Maria Popova and Oxana Shevel 2024

The right of Maria Popova and Oxana Shevel to be identified as Authors of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2024 by Polity Press

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

111 River Street

Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-5736-3 (hardback)

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-5737-0 (paperback)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Catalogue Number: 2023932868

by Fakenham Prepress Solutions, Fakenham, Norfolk NR21 8NL

The publisher has used its best endeavors to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Abbreviations

ATO

Anti-Terrorist Operation

BSF

Black Sea Fleet

CBR

Central Bank of Russia

CCU

Constitutional Court of Ukraine

CEC

Central Election Commission

CES

Common Economic Space

CIS

Commonwealth of Independent States

CSCE

Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe

DCFTA

Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area

DNR

Donetsk People’s Republic

ECHR

European Court of Human Rights

EU

European Union

FSB

Federal Security Service

GUAM

Georgia, Ukraine, Azerbaijan, Moldova

KGB

Committee for State Security

KIIS

Kyiv International Institute of Sociology

KPU

Communist Party of Ukraine

LDPR

Liberal Democratic Party of Russia

LNR

Luhansk People’s Republic

MAP

Membership Action Plan

MP

Member of Parliament

NABU

National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine

NATO

North Atlantic Treaty Organization

NAZK

National Agency for Corruption Prevention

NDI

National Democratic Institute

OSCE

Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe

OCU

Orthodox Church of Ukraine

OUN

Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists

PIC

Public Integrity Council

PLC

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

PR

Party of Regions

ROC

Russian Orthodox Church

SAPO

Special Anti-Corruption Prosecution Office

SBU

Security Service of Ukraine

SMD

Single Member District

SPS

Union of Right Forces

UAOC

Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church

UGCC

Ukrainian Green Catholic Church

UNESCO

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

UNR

Ukrainian People’s Republic

UOC-KP

Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Kyiv Patriarchate

UOC-MP

Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate

UPA

Ukrainian Insurgent Army

USSR

Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

ZUNR

West Ukrainian People’s Republic

Illustrations

Tables

1.1 December 1991 independence referendum vote in Ukraine, and ethnic Russians and Russian-speakers in Ukraine’s regions, 1989 vs 2001

Figures

2.1 Political regime divergence in Russia and Ukraine

7.1 Support for EU and NATO membership in Ukraine

7.2 Growth of Ukrainian civic identity

Maps

2.1 Regions where pro-Western parties won the party list vote in parliamentary elections, 1998–2019

4.1 Waves of EU enlargement

4.2 Waves of NATO enlargement

Acknowledgments

In the frenzied first weeks of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the two of us, graduate school friends, who had worked on both Russian and Ukrainian politics for more than two decades, talked every day as we sought to make sense of how Putin could widen this criminal war of aggression when he should have known that Ukraine would resist with all its might. We also strove to counter the prevailing impression that Ukraine’s spirited resistance was surprising and, perhaps, futile. Had Louise Knight from Polity Press not approached us, we might have stuck to writing short pieces and op-eds and talking to the media. We are grateful to her for the encouragement to write a book where we could go deeper into the root causes of Russia’s war on Ukraine. We thank Louise and Inès Boxman for their guidance, responsiveness, professionalism, and flexibility throughout the entire process – from idea to finished product.

We are incredibly lucky to be part of a highly supportive network of colleagues and friends, who listened to our ideas, read early drafts, suggested relevant literature, helped edit, shared data, and offered constructive suggestions and criticism. Of course, all mistakes and omissions are our own responsibility. We started the book at a writing retreat in Budapest, which was organized by the BEAR Network, headed by Juliet Johnson and Magdalena Dembińska and managed by Sasha Lleshaj. We thank the Jean Monnet Centre Montreal, and especially Anastasia Leshchyshyn, for organizing a book manuscript workshop for us in Montreal, where we received invaluable advice from Dominique Arel, Yoshiko Herrera, Juliet Johnson, Andrew Kydd, Matthew Pauly, and Lucan Way. Dominique Arel, Juliet Johnson, Marko Klasnja, Mark Kramer, Alexander Lanozska, Anastasia Leshchyshyn, Catherine Lu, Lorenz Luthi, and Matthew Pauly read and commented on various parts of the manuscript and at various stages, and offered great suggestions. The anonymous reviewers also offered helpful advice. We thank Volodymyr Paniotto for sharing Ukrainian polling data. Yoshiko Herrera and Catherine Lu went above and beyond and were immensely generous with their time, knowledge, and friendly encouragement.

We thank our families for patiently bearing with us, while we often worked late nights, skipped family outings, and talked loudly on Zoom for hours. Thanks to George, Emilia, and Miljenko for making it possible for Maria to work around the clock when it was necessary and to Viktor, Anton, and Max for listening to many unsolicited lectures at dinnertime. Viktor also pitched in with some last-minute but much needed research assistance. Isabella wants to know why Putin attacked Ukraine and when she’s a little older she can read the book to find out. Sofia made it possible for Oxana to work at all hours and cheered her on. Oxana’s family and friends in Ukraine have not only been a source of encouragement but also a living proof of the resilience, faith in victory, and unbreakable spirit of the Ukrainian people.

Introduction:Russia’s invasion and Ukraine’s resistance

At dawn on February 24, 2022, rockets rained on Ukrainian cities and the nearly two hundred thousand troops Russia had amassed on Ukraine’s borders over months, allegedly for training exercises, rolled into Ukraine. A forty-mile Russian military column headed straight for Kyiv to take over the capital and overthrow President Zelensky’s government. In a nearly hour-long speech, Russian President Vladimir Putin justified this “special military operation” as an act of self-defense. The Kyiv government, Putin claimed, was controlled by “neo-Nazis,” was “perpetrating genocide” of Russian-speakers in eastern Ukraine, and the Ukrainian military, strengthened through Western training and armament, was posing a security threat to Russia. To reduce the danger, in Putin’s words, Russia had to “de-Nazify” and “demilitarize” Ukraine. Anyone trying to stop Russia would face consequences they had never seen in their history, Putin warned, in a thinly veiled nuclear threat.1 Western intelligence had warned for months about an expected Russian military incursion in Ukraine. But Russia shocked the world by unleashing the biggest land war in Europe since World War II to achieve the explicit and maximalist goal of conquering Ukraine.

The second surprise was Ukraine’s spirited and effective resistance. Putin, and many in the Russian army, expected that the “special military operation” would last mere days or short weeks, and that Russian troops would be greeted as liberators from “Nazi” rule by grateful Ukrainian citizens. The West’s estimation of Ukraine’s capacity and commitment to defend itself was similar. The German finance minister reportedly told the Ukrainian ambassador that Ukraine had just hours before it would be defeated by Russia. Military experts debated when Kyiv would fall, not whether. Pundits started thinking about what Russian occupation of Ukraine would look like.2 But reality turned out to be dramatically different. On February 26, Western partners offered President Zelensky evacuation options for him and his family to leave the capital but, instead of accepting them, he filmed himself in the center of Kyiv to rally Ukrainian defenders, saying “I am here. We are not putting down arms. We will be defending our country.”3 Volunteers flooded military recruitment centers, the government gave them arms, and civil society sprang into action to support the war effort by crowdfunding military supplies, organizing delivery logistics, and providing humanitarian aid.

By early March, the Ukrainian military and the territorial defense forces, where regular citizens enrolled to defend their home regions, stopped Russian armored columns on their way to Kyiv. By the end of March, Russia lost the battle for Kyiv, and had to withdraw from the capital region. By April, Putin’s blitzkrieg to overrun Ukraine was a clear failure, and Russia regrouped and continued to fight in the east and the south. By late May, Russia lost as many servicemen as the Soviet Union did in ten years of war in Afghanistan.4 In the fall of 2022, Russia tried to formalize its land grab by organizing sham referenda and then annexing four Ukrainian regions into the Russian Federation. Undeterred by nuclear saber-rattling, Ukraine started a counteroffensive, which liberated first areas around Kharkiv in the east, and then Kherson in the south, the only Ukrainian regional center that Russia had managed to capture in the beginning of its invasion. Russia’s mobilization in the fall and the recruitment of tens of thousands of convicts into the regime-sponsored private mercenary group Wagner did not help Russia regain initiative in the war, but only led to its mounting casualty counts. In 2023, Ukraine continued to try to push Russia out of all its territory and launched a counteroffensive in June, while Russia held on to its maximalist goal of conquering as much of Ukraine as possible.

The root of the war: Russian re-imperialization vs. Ukrainian independence

The scale of the Russian invasion and the effectiveness of Ukrainian resistance both defied expectations. Why did Russia try to overthrow its neighbor’s government and conquer the entire country? How did Ukrainians manage to withstand a full-scale invasion by the world’s second most powerful military? Why did diplomacy fail to avert Russia’s aggression? We argue that an escalatory cycle between Russian imperialism and Ukraine’s commitment to its independent statehood that started in the wake of the USSR’s dissolution in December 1991 led to this war. The 2022 Russian invasion was the culmination of this escalatory cycle and the final, destructive phase of the collapse of the Soviet empire. The more Russia sought to fulfill its vision of restoring control over Ukraine, the more Ukraine pulled away and tried to consolidate independence. Ukraine adopted domestic policies emphasizing the distinctiveness of the Ukrainian nation, de-emphasized links with Russia, and gradually shifted to a Euro-Atlantic foreign policy. Each such step was viewed with hostility in Russia and increased its imperial drive. The central place that Ukraine occupied in Russia’s national imaginary and its geopolitical centrality to any future Russia-led polity meant that Russia cared the most about Ukraine’s political trajectory relative to the rest of the post-Soviet states. The escalatory cycle was therefore the most obvious and the most consequential in Russia–Ukraine relations but it is a generalizable pattern that can be analyzed across the post-Soviet region.

The escalatory cycle produced two dramatically different polities. Russia became a consolidated autocracy led by a revanchist dictator, bent on restoring the empire, and sustained by a passive society, which appreciated great power status more than democracy. Ukraine built a competitive, if imperfect, democracy with a vibrant civil society, a strong sense of its nationhood, and a commitment to its independence. Moreover, by 2022, Russia and Ukraine perceived each other as their antithesis. Unwilling to accept or even acknowledge Ukraine’s homegrown commitment to forge its own domestic and foreign policies, Russia viewed its neighbor as a fundamentally anti-Russian project, steered by a hostile West. Having failed to bring the recalcitrant “younger brother” back into the fold through hybrid warfare – disinformation and destabilization through the intervention in the east – Russia escalated to a full-scale invasion. For Ukraine the coerced return to Russia’s new supranational project known as the Russian World (Russkii Mir) had become an existential nightmare. Resisting Russia’s invasion became Ukraine’s fight for survival as a state and a nation.

What triggered this escalatory cycle? And did the cycle lead the countries inexorably into a collision course – or could the divergence that it produced have been bridged? The trigger was the misaligned understanding of the 1991 dissolution of the USSR. Although Russian president Boris Yeltsin and his Ukrainian counterpart, Leonid Kravchuk, along with Belarusian leader Stanislau Shushkevich hammered out the Belavezha Accords, disbanding the Soviet Union together, they imagined the aftermath differently. Russia’s leadership assumed that the newly created Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) would be a union of nominally independent states, but united as before in the economic, political, and security spheres, with Russia in the lead. Over time, centripetal forces would bring the former republics back together, the process aided by successful market reforms that would increase Russia’s attractiveness as the center of gravity, many in Yeltsin’s camp reasoned. By joining other republics’ push for independence from the USSR, Yeltsin thought he was reinventing the union state, rather than destroying it.

The Ukrainian leadership, on the other hand, believed that the Belavezha Accords were a starting point on the road toward greater independence and separation between the former union republics in all areas, save possibly economic cooperation. In this sense, the CIS creation was, for Yeltsin, re-written vows for continued marriage, while Kravchuk famously called it a “civilized divorce.” In Ukraine, the majority of the political class united behind the idea of an independent state. For some, Ukrainian independence was a long-held dream for which they had long advocated and suffered repression under the Soviet rule. But for many others independent statehood held a practical rather than ideational appeal. Already in the late Soviet period some of the former communist elites in Ukraine decided to back independence, drawn to the idea by perceived economic opportunities, political prestige of being in charge of a state rather than a province, and autonomy to make decisions without Moscow oversight. This alliance between national-democrats ideologically committed to independent Ukraine, and centrist former communists supporting independence for pragmatic reasons was an informal grand bargain that shaped policies in Ukraine. Originally, the push away from Russia was the product of these elite decisions. While Ukrainians overwhelmingly voted for independence in 1991, the economic hardship of the 1990s created political divisions, with the median voter often taking somewhat more “pro-Russian” positions than the elites. Over time and, in part due to Russia’s actions, popular preferences evolved – first in the strategically important and electorally sizeable center of the country, and after Russia’s aggression in 2014 in the east and south as well.

Since 1991, therefore, Ukraine defied Russia’s expectation that it would be tied back to it, but the resistance was originally moderate, unfolding in fits and starts. Successive Ukrainian governments pursued nation-building policies that were more limited than the most committed Ukrainian nation-builders preferred, but still included symbolic statehood-strengthening measures such as Ukrainian-only state language, the rejection of dual citizenship with Russia, and the re-evaluation of shared history. Russia found all these policies objectionable. In foreign policy, Ukraine pushed against Russia’s re-imperialization initiatives and initially sought to develop a multi-vectoral foreign policy aimed at balancing between Russia and the West. Russia objected at each step even to modest Ukrainian attempts to craft an independent foreign policy, but reacted with only moderate interference.

Russia’s methods included both carrots and sticks: trade barriers, preferential energy prices or price gouging, and diplomatic pressure to sign on to supranational cooperation structures. The interference was moderate for two reasons. First, Russia was constrained by its own state weakness and domestic crises. Second, in the 1990s, it was reasonable for Russia to expect that moderate interference could be sufficient. By pressuring Ukraine through economic levers, obstructing some of Ukraine’s separation initiatives such as delimitation and demarcation of the shared border, and using the CIS framework to pursue integration measures, Russia could hope to halt and eventually reverse the separation process. However, the 1990s ended without a decisive re-imperialization success. Successive Ukrainian governments consistently resisted Russian attempts to establish closer political or military integration and committed to maintaining equal partnership with Russia and the West.

The end of the first post-Soviet decade saw a leadership change in Russia when President Yeltsin resigned and handed the reins to Vladimir Putin. Putin immediately embarked on the creation of a power vertical, which entailed regional centralization, strengthening state power over the economy, and consolidation of political power in the hands of the president. He started a second war in Chechnya, which hastened the erosion of civil and political rights. He also moved to impose control over the oligarchs who had emerged and wielded political power during Yeltsin’s term. Political competition in Russia rapidly declined.

Meanwhile, in some intended vassals, especially in Ukraine, the political trajectory pointed to strengthening political competition. First in Georgia in 2003, and then in Ukraine in 2004, authoritarian, pro-Russian incumbents lost their grip and ceded power after popular mobilization against electoral fraud. Both color revolutions (“Rose” in Georgia and “Orange” in Ukraine) were significant setbacks for Russia’s imperial ambitions. In Ukraine, popular mobilization prevented the pro-Russian candidate, Viktor Yanukovych, from taking office and instead brought to the presidency Viktor Yushchenko, a pro-Western reformist former prime minister. Yushchenko’s victory resulted in a Ukrainian government strongly committed to pro-Ukrainian identity politics and more ambitious about Western integration. Russia interpreted the Orange Revolution through its imperial lens, which could not envision a Ukrainian domestic political dynamic and majority popular sentiment that would be different from Russia’s. The imperial mindset could only conceive of Ukrainians’ mobilization as instigated and backed by the West and ultimately aimed at weakening Russia.

The color revolutions were highly contingent critical junctures. If they had failed, authoritarian regimes across the post-Soviet region would have entrenched. But those revolutions that did succeed in unseating the wannabe authoritarians fostered Russian paranoia that the West was “stealing” or “luring away” Russia’s rightful vassals and threatening Russian regime stability too. Russia started seeing the domestic politics of Ukraine as a tug of war between itself and the West, as opposed to a political process determined by the evolving preferences of the Ukrainian electorate and domestic political competition. The Russia–West relationship soured as a result.

In Ukraine, the Orange Revolution ushered in the first decisive departure from Russia’s preferred vision of Ukraine’s past and future. Yushchenko spearheaded legislation that recognized the murderous famine of 1932–1933 (Holodomor) as a genocide of the Ukrainian people. Russia vehemently objected, insisting on characterizing the famine as “a common tragedy of the Soviet people.” To Russia’s wrath, Yushchenko also tried, albeit unsuccessfully, to foster the creation of an Orthodox Church in Ukraine, independent of Moscow, and to legislate recognition as war veterans and fighters for Ukrainian independence to members of the Ukrainian nationalist formations who had fought against the Soviet Union during and after WWII. In foreign policy, Yushchenko rejected Ukraine’s status as Russia’s vassal and moved away from the multi-vector policy of his predecessors. He expressed Ukraine’s desire for a European future more forcefully. Under his leadership in 2007, Ukraine started negotiations with the European Union (EU) on a comprehensive and ambitious association agreement – Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA) – which could be a stepping-stone on Ukraine’s path to EU membership. Yushchenko also applied for a NATO Membership Action Plan (MAP) in 2008, but was rebuffed by NATO, which offered only a vague promise to consider Ukrainian membership someday.

In 2010, Ukrainians narrowly elected as president pro-Russian Viktor Yanukovych, who had lost the Orange Revolution elections. In the first few years of the 2010s, it seemed that Russia’s objective to turn Ukraine into a reliable vassal was on track to be realized. Yanukovych embarked on authoritarian power consolidation, bringing Ukraine’s political model closer to Russia’s. He quickly back-pedaled on the 1930s famine interpretation, revised memory politics to mimic Russia’s, elevated the legal status of the Russian language, extended Russia’s Black Sea Fleet presence in Ukraine, and reversed Ukraine’s expressed interest in NATO membership.

However, the strength of the pro-Western constituency in Ukraine, along with continued, though curtailed, political competition meant that domestic pushback prevented Yanukovych from taking pro-Russian policies too far. Yanukovych continued the Yushchenko-initiated negotiations with the EU, albeit more slowly and tentatively and, by the fall of 2013, Ukraine was ready to sign the association agreement. Russia did not tolerate this manifestation of an independent Ukrainian foreign-policy course. In 2011, Russia launched a competing supranational initiative to the EU (the Eurasian Customs Union, later Eurasian Economic Union) aimed at bringing the vassals closer and cutting off their road to EU integration. To stop Ukraine from pursuing the European integration path, in 2013 Russia mounted a trade war, meant to illustrate, in the words of Putin’s advisor, that Ukraine would be making a “suicidal step” by signing the EU agreement.5 Then, in November 2013, Putin and Yanukovych met in secret and Russia successfully strong-armed him at the eleventh hour to renege on the signing of the EU association agreement. The failed signing triggered a reaction in Ukrainian society that neither the Yanukovych government nor Russia could control. The Euromaidan street protests exploded in November, quickly swelled and, after violence escalated and the regime killed dozens of protesters, culminated in the crumbling of Yanukovych’s government and his flight from Ukraine. Like with the Orange Revolution, Russia interpreted Euromaidan through its imperial lens and saw the protest as an American-orchestrated coup “to steal” Ukraine from Russia and lure it to the West. Russia could not recognize it for the domestic mobilization that it was. Following Euromaidan’s victory, Russia lashed out against the new government in Kyiv, characterizing it as an “illegal fascist junta.” It then initiated a disinformation campaign, targeted at the Ukrainian, Russian, and Western public, claiming that Yanukovych did not flee Kyiv hoping to figure out how to hold onto power as his government crumbled, but was deposed in a US-backed coup.

The escalatory cycle between Russia’s desire to control Ukraine and Ukraine’s commitment to independent statehood helps us to understand why Russia reacted militarily against Ukraine in 2014, rather than employing the non-military means of pressure at its disposal and waiting for Ukraine’s regionally divided electorate again to bring to power a Russia-friendly president in the subsequent round of competitive elections. Euromaidan was a watershed event, as it ushered in a government that was the most pro-Western and, to Russia’s eyes, anti-Russian that Ukraine had ever had. To Russia, this fiasco demonstrated that the non-military levers it had used up until then to keep Ukraine in its sphere of influence had been insufficient. Russia concluded that a stronger reaction was now warranted, in order to achieve its goal of controlling Ukraine.

This reaction started with the annexation of Crimea immediately after Yanukovych fled, when “little green men” – Russian troops without insignia – seized state institutions and Ukrainian military bases. The success of the operation was facilitated by the presence of Russian troops and the Black Sea Fleet in Crimea to which Ukraine had agreed when the USSR fell apart, by the sheer surprise and speed of the brazen operation, and by the West urging restraint on Ukraine. Within barely two weeks, Russia staged a “referendum” in Crimea on the peninsula’s fate. The vote fell well short of international standards for free plebiscite but officially delivered a majority for Crimea leaving Ukraine and joining Russia.

The next step in Russia’s covert military aggression against Ukraine was the so-called “Russian Spring” project. The operation was supposed to drive a wedge between southeastern Ukraine and the new government in Kyiv. In the southeastern regions – Odesa, Kherson, Mykolaiv, Zaporizhzhia, Kharkiv, Dnipropetrovsk, Donetsk, Luhansk, labeled Novorossia in Russia, referencing an old imperial construct – Russia and Russian operatives amplified local dissatisfaction with the change of government in Kyiv hoping to trigger a regional rebellion that would break up Ukraine. This plan failed almost everywhere because Russia misjudged domestic sentiment in these regions. The Kremlin assumed that the Russian-speaking population in the south and east of Ukraine, many of whom had opposed Euromaidan, would also support separating their region from Ukraine. Only in parts of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, collectively known as Donbas, did Russia’s interference succeed in creating the self-proclaimed Donetsk and Luhansk “people’s republics” (the DNR and the LNR) and in fostering an armed insurgency, which challenged the central government militarily. In April, the Ukrainian interim government launched a military campaign to try to restore its control over Donbas. In the summer of 2014, Russia sent in regular troops, as the Ukrainian army was gaining the upper hand against the rebellion on the battlefield. Russia’s intervention turned the tide and forced Ukraine to sign two disadvantageous accords in Minsk in September 2014, and again in February 2015, to avoid losing even more territory.

The escalatory cycle between Russian imperialism and Ukraine’s commitment to its independent statehood played out by heightening anti-Russian sentiments in Ukraine in response to Russia’s 2014 aggression. Instead of scaring Ukrainians out of pursuing a pro-Western policy course and forcing them to accept that they were in Russia’s sphere of influence, Russia’s attempt to bring Ukraine back into the fold through force boosted support for EU and NATO membership in all regions of Ukraine. A September 2014 survey conducted by Gallup on behalf of the International Republican Institute showed that support for membership in the EU, which stood at 42% in September 2013, rose to 59% by September 2014, while support for joining the Russia-led Customs Union fell from 37% to 17%. Support for Ukraine’s membership in NATO, which in the years before Euromaidan hovered around 20%, also increased markedly. By September 2014, a plurality of 43% supported NATO membership. In the following months and years support for both EU and NATO solidified.

Post-Euromaidan elections produced successive, reliably pro-Western governments. Ironically, the annexation and occupation of Ukraine’s most Russia-leaning regions by Russia and its proxies took millions of pro-Russian voters out of the voting electorate, dramatically changed the electoral equation, and made the formation of a future pro-Russian Ukrainian government virtually impossible. The new electoral geography and shifting public opinion in Ukraine also meant post-Euromaidan governments adopted more policies which infuriated Russia. They signed the association agreement with the EU, which Yanukovych and Russia had sought to prevent, enshrined the goal of NATO and EU membership in the constitution, accelerated Ukrainization through a series of new legal measures, contributed to the formation of an Orthodox Church independent of Moscow, and launched decommunization aimed at removing a variety of Soviet-era legacies from Ukraine. As part of the new close relationship with the EU, Ukraine also started implementing a series of reforms of its state institutions (police, courts, local government, etc.), which put it on track to meeting membership criteria for the EU, and strengthened its democracy. Rather than returning to the Russian World, Ukraine was drifting farther away with each passing year.

In 2019, democratic competition produced another turnover in power. Post-Euromaidan president Petro Poroshenko lost to Volodymyr Zelensky, a Russian-speaker from the south of Ukraine, who campaigned on readiness to come to an agreement with Russia on Donbas as well as Crimea. Russia expected that its gamble from 2014 would finally pay off and the insurgent Donbas entities it fostered and consolidated after 2014 would serve as Trojan horses inside Ukraine. If given “special status” within Ukraine on the terms reflecting Russia’s preferred interpretation of the Minsk peace agreements, the LNR and DNR would wield de-facto veto power over the policies of the government in Kyiv, putting Ukraine back on the vassal track. However, even a conciliatorily predisposed Ukrainian president saw the danger to Ukrainian sovereignty that Russia’s reading of Minsk posed. Among the Ukrainian public, despite majority support for a negotiated settlement of the Donbas conflict, there was majority opposition to giving LNR and DNR the powers that Russia demanded. The Minsk process deadlocked and, with it, Russia’s objective of vassalizing Ukraine.

Russia’s response was to escalate its methods for achieving the vassalization of Ukraine yet again. First, it implicitly threatened a full-scale invasion by amassing troops along Ukraine’s border, starting in the fall of 2021. Second, in a bid to blackmail the West into delivering a vassalized Ukraine, Russia posed unrealistic demands to the NATO alliance. In December 2021, Russia handed to the US the text of a treaty it wanted the US to sign. The treaty demanded a ban on further NATO expansion, withdrawal of NATO troops and weapons from the post-communist member states, and a ban on all military cooperation between NATO and post-Soviet non-NATO countries, such as Ukraine. Taking these demands only to the US revealed that, just as Russia views its post-Soviet neighbors as vassals, it likewise views European NATO members as American vassals. The US could not agree to these demands, which were essentially an attempt at blackmail, and went against the principle of sovereign states having the right to decide their foreign-policy alliances, as well as NATO’s collective decision-making principle. Russia’s escalation and attempt to blackmail the West failed.

Ukraine also stood firm because it was committed to resisting reincorporation into the Russian World. Ukraine knew full well that neutrality and Minsk implementation on Russia’s terms were interim steps toward Russia achieving its ultimate goal of vassalizing it. Conceding neutrality after the annexation of Crimea and the loss of territory in Donbas would have been a creeping loss of sovereignty.

Acquiescing to separatist entities holding veto power over a swath of state policies would have cemented this sovereignty loss. For the Zelensky government, therefore, meeting Russia’s demands either on neutrality or on the implementation of the Minsk accords on Russia’s terms, while hypothetically possible, in practice was unrealistic because Ukrainian society would largely interpret the steps as unacceptable surrender to Russia. By early 2022, 62% nationwide and a majority in every region except the east supported NATO membership.6 Majority opposed concessions to Russia on Minsk – only 11% believed that Ukraine should be implementing the agreements.7 Had Zelensky tried to push through these measures, street protests and political instability were sure to follow and he would have most likely been unable to put together the legislative majority required to amend the relevant parts of the constitution. A likely failure to impose these measures on Ukrainian society would have denied Russia’s goal of vassalization, and thus put the Russian invasion back on the agenda. But Ukraine would be facing the invasion with a less trusted government, a weakened state, and a potentially more divided society.

In sum, over the last three decades, the escalatory cycle that characterized the Russian–Ukrainian relationship led to increasing divergence between the two countries in multiple dimensions: identity conceptions, regime dynamics, and geopolitical orientation. In Russia, the state and the nation became increasingly conceptualized in civilizational-imperial terms, whereas Ukraine solidified a distinct Ukrainian identity committed to independent statehood. Under Putin’s rule, Russia consolidated an increasingly repressive and personalistic authoritarian regime, which felt threatened by Ukrainian democracy’s progress and resented its increasingly pro-Western foreign policy. The robust civil society and vibrant political competition flourishing in Ukraine looked like a nightmare scenario from the perspective of Russia’s authoritarian regime – a dangerous example that Russia’s democratic opposition could try to emulate, with Western instigation. In foreign policy, Putin’s Russia became increasingly anti-Western and bent on asserting Russia’s dominance over the post-Soviet states, first and foremost Ukraine, at the same time as Ukraine committed to a European path. Russia’s imperial vision came to dominate policy-making vis-à-vis Ukraine, as Ukraine increasingly slipped away from Russia’s grasp.

The methods Russia used to push Ukraine to change course escalated from diplomatic pressure, energy flow carrots and sticks, information warfare, and cyber-attacks to military aggression. Each escalation of pressure by Russia prompted an ever-increasing share of Ukrainians to shift from pro-Russian to pro-Western positions, to embrace more distinctly Ukrainian identity, and to support more decisive Ukrainization policies. As a result, while each Ukrainian incumbent sought to balance between a pro-Russian and a nationalizing or pro-Western position, the equilibrium changed over time. Each pro-Western incumbent became more determined to pursue Euro-Atlantic integration, while each pro-Russian incumbent was less in step with public opinion. This trend in turn boosted Russia’s paranoia that the West was stealing Ukraine. The result of this escalatory cycle of divergent trajectories was two incompatible domestic equilibria – Russia became committed to resetting Ukraine as a loyal vassal, while Ukraine became convinced that it had to leave Russia’s sphere of influence altogether and join the West.

Was the 2022 war inevitable?

War is never inevitable. Russia’s President Putin made calculated decisions to invade Ukraine both in 2014 and in 2022. He could have instead continued pursuing the goal of establishing control over Ukraine through other means or he could have grudgingly accepted the reality of Ukraine’s distancing from Russia. Ultimately, the heavy moral responsibility for the murder and destruction of the invasion lies with him and his regime.

Our escalatory cycle argument developed in this book addresses whether the divergence between Ukraine and Russia was pre-determined and whether it was pre-ordained that divergence would produce a collision course between the two states, rather than mutual acceptance of the difference. We explain why both divergence and the collision course were the likely outcome but we also show that neither was inevitable and there were plausible alternative scenarios that could have averted the war. The war in 2022 was a logical step in the escalatory cycle, but throughout the post-Soviet period there were critical junctures where either Ukraine or Russia could have swerved and pursued a different trajectory.

The logic of an escalatory cycle between re-imperialization and independence centers on the compatibility between Russia’s and its neighbors’ foreign and domestic policies. When the vassals pursue parallel foreign policy and refrain from emphasizing “anti-Russian” identities domestically, Russia does not need to exert its imperial power. In relations with Ukraine, this compatibility would have been more likely if they had developed similar regimes. If both countries were autocracies, it would have been easier for Russia to re-establish control over Ukraine. An authoritarian trajectory for Ukraine would have meant a more pro-Russian course in foreign and domestic policies alike. Had Yanukovych prevailed during the 2004 Orange Revolution or successfully crushed Euromaidan, he could have entrenched himself as an authoritarian Ukrainian leader who would look to Russia for backing. As the price for its support, Russia would have demanded aligned identity politics and closer political integration.

If Russia had de-imperialized and accepted the sovereignty of its former vassals, a collision course also would have been unlikely. Russia would have recognized Ukraine’s right to formulate domestic policies without input or pressure, without taking Russia’s preferences into consideration. Even if Russia found such policies objectionable it would not have tried to change by force the domestic policies of a state whose sovereignty it accepted. Acceptance would have prevented Russia from perceiving itself in a zero-sum game with the West for control of Ukraine. This way, “either we control it, or they do; Ukraine as nobody’s vassal or proxy cannot exist.”

If Russia had managed to establish a democracy, even without de-imperialization, its imperial impulses may not have taken it all the way to military aggression either. Regular competitive elections could have empowered a variety of voices which, even if for the most part sharing imperialist goals, would have disagreed on the ways to achieve them. Minority voices advocating a non-imperial identity would have played a greater role in a democratic environment than in an authoritarian one. In this environment, military aggression would have become less likely also because advocates of alternative methods could have voiced their criticisms in public and influenced the policy-making process. Even among the imperialists who favored restoring the USSR or the Russian empire, the proponents of military aggression would have had to win over those favoring milder means toward similar goals, with Russian society further being in a position to affect the outcome of elite disagreements through electoral politics. Russia could have tried to build a liberal economic empire across the former Soviet region, as some Russian politicians have advocated. Such an empire might have been attractive to Ukraine, and Russia may not have had to resort to bullying, blackmail, and aggression to keep Ukraine in its orbit.

Neither of these things happened. Ukraine did not end up as a pro-Russian autocracy and Russia did not maintain political competition. Democratic competition in Russia peaked in the 1990s and only went downhill from there. By 2014, Ukraine was fully committed to independence and increasingly leaned West, while Russia came to see Ukraine’s full independence as an anti-Russian project engineered by the West, ultimately aimed against Russia, and was determined to destroy it. In several chapters, we discuss various windows of opportunity during which the escalatory cycle could have been broken and the processes, by design or by fiat, that slammed them shut.

Could the West have prevented the war?

Western containment of Russia may have stood a chance of averting the war. After Russia invaded Georgia in 2008 and Ukraine in 2014, some argued that the West should have concluded that it pushed Russia too much and disregarded its legitimate concerns about its waning influence in its neighborhood. But the West should have drawn the opposite lesson. Instead of worrying about provoking Russia, the West should have recognized that Russia sought to restore the vassal status of its neighbors left out of the EU and NATO, and 2008 and 2014 were just the beginning of an aggressive re-imperialization campaign. Redesigning Europe’s security architecture against, rather than with Russia could have preserved peace.

A Western containment strategy could have included sustained efforts to counter Russia’s efforts to undermine Western democracies through disinformation campaigns, illegal party financing, and electoral meddling. Instead of a “reset,” the US could have championed extensive sanctions after the 2008 Russian invasion of Georgia. A robust Western response to the intervention in Georgia could have deterred Russia from its opportunistic land grab in Ukraine in 2014. Instead, the equivocating Western response in 2008 led Russia to perceive the West as weak and declining, divided, and not committed to preventing Russia from re-establishing dominance over its neighbors. The 2008 financial crisis and the West’s introspection and focus on overcoming it through domestic reforms only boosted Russia’s perception that the opportunity costs of re-Sovietizing its neighboring region were going down.

In 2014, the West again decided against trying to contain Russia. More far-reaching sanctions and Western unity to isolate Russia could have made the costs of Russian imperialism high enough to deter the 2022 invasion. Europe, and especially Germany, should have reduced its energy dependency on Russia instead of proceeding with Nord Stream 2. The US under both the Obama and the Trump administrations should have provided more extensive military aid to Ukraine to drive home to Russia the message that it cannot hope to easily overrun Ukraine militarily. Instead, the West prioritized engagement and de-escalation, fearing that arming Ukraine would provoke Russia and rationalizing that arming Ukraine would not make a difference on the battlefield. We now know that engagement did not work. In hindsight containment seems like the better strategy to prevent the war.

The narrative of an aggressively expansionist West luring Eastern Europe into NATO and then setting its sights on Ukraine and other post-Soviet states is unconvincing and not supported by facts. On the contrary, the West prioritized a cooperative relationship with Russia and strove to include it in Europe’s security architecture, often over the objections and security concerns of the East Europeans. The West did not push the East Europeans into NATO. On the contrary, those who did make it into NATO campaigned hard and overcame initial Western skepticism to achieve it. The West was not only cognizant of Russia’s preferences, but tiptoed around them because it sought Russian cooperation more broadly on the international scene. The West hoped that engagement with Russia through trade and other forms of cooperation would be beneficial to all. After 2001, the West also solicited Russia’s cooperation in the management of conflicts in the Middle East and Afghanistan, in containing Iran’s nuclear program, and in counteracting Islamic terrorism. Even after Russia’s 2014 aggression against Ukraine, the West sought a solution that would be acceptable to Russia by backing the Minsk process, offering Ukraine modest military aid, and no security guarantees. The 2022 full-scale invasion is surely Putin’s fault, but the West should have tried harder to deter him.

Book outline

This book argues that the key to understanding Russia’s attack on Ukraine and Ukraine’s fierce resistance lies in examining the trajectories Russia and Ukraine pursued since the collapse of the Soviet Union, and how an escalatory cycle between Russia’s re-imperialization goal and Ukraine’s commitment to its independence produced increasing divergence. The 2022 aggression was a surge by an autocratic Russia increasingly confident in its ability to re-imperialize the former Soviet region, rather than the desperate reaction of a Russia, scared and cornered by the West. Ukraine’s resistance was a determined stand against its Russia-ascribed fate. Ukraine surprised not only Russia, which, seeing Ukraine as not a “real” nation, denied it any agency, but also many Western observers and analysts, who viewed the post-Soviet region through a Russocentric lens or focused on “great powers” dynamics.

The next chapter starts with a summary of Ukraine’s and Russia’s entangled histories and competing interpretations of this entanglement. These interpretations can present historical events as either justifications for “organic unity,” thus strengthening contentions that Ukraine and Russia have always been destined to be together, or, conversely, as evidence of Ukraine and Russia’s distinctions going back centuries, and Russia’s repeated attempts to suppress independent Ukrainian identity and its quest for political autonomy. The chapter then surveys the trajectory of identity formation in post-Soviet Ukraine and Russia, which were in large part informed by competing interpretations of history. The chapter explains how and why in Russia the search for a post-Soviet identity was a competition between a civic-territorial ideal and an imperial-expansionist one, with the latter one eventually gaining the upper hand. In Ukraine, there were also competing intellectual constructs of a “true” Ukrainian nation, but already in the late perestroika period, identity politics resulted in state elites embracing a conception of national identity that underscored Ukraine’s distinctiveness from Russia. The chapter explains how national-democrats ideologically committed to independent Ukraine and centrist former communists supporting independence for pragmatic reasons formed an informal Center-Right grand bargain, which shaped identity policies in Ukraine.

Chapter 2 focuses on the regime divergence between Ukraine and Russia. Why was Ukraine able to establish a competitive, if messy democracy, and why did Russia, after a period of political openness in the 1990s, revert to authoritarianism under Putin’s tenure? The chapter traces the parallel political and economic trajectories in the 1990s, pinpoints the beginning of decisive divergence to 2004 in the wake of Ukraine’s democratizing Orange Revolution, and then identifies the last opportunity for breaking the escalatory cycle and resuming parallel regime paths in the early 2010s. 2010 to 2014 could have brought about either collapse of Ukraine’s democracy and a decisive re-orientation away from the EU and toward Russia, or a democratization breakthrough in Russia, which could have put it on a de-imperialization path. Neither happened, but we discuss some counterfactuals to illustrate how things could have turned out differently.

Chapter 3 discusses how the divergence in identity politics in Russia and Ukraine discussed in Chapter 1 led to divergence in the specific identity policies that the two states adopted. As this chapter shows, starting already in the late Soviet period, Russia and Ukraine pursued increasingly contrasting policies in the sphere of historical memory, language, and citizenship. On the logic that the legitimacy of an independent state rests on the presence of a distinct nation, Ukrainian state elites – including those who themselves were Russian-speakers – pursued nation-building policies that legitimized and fostered a distinct Ukrainian nation. Russia disliked, regularly objected to, and sought to change Ukraine’s identity policies. Russia’s opposition to Ukraine’s nation-building agenda intensified with Putin coming to power and a re-imperialization of Russian identity followed. The persisting and growing divergence in identity policies illustrates the reinforcing cycle of Ukraine’s pull away from Russia and Russia’s unsuccessful attempts to reverse the process. The chapter also discusses how, originally, Ukraine’s identity policies were the product of these elite decisions taken within the logic of the Center-Right grand bargain, while popular opinion was divided, with the median voter position often more “pro-Russian.” Over time popular opinion evolved – first gradually, starting in the geographic center of the country, and after the 2014 Russian aggression more rapidly, and now unfolding in the east and south as well.

Chapter 4 discusses the geopolitical interaction between Russia, Ukraine, and the West until 2014. It explains that the domestic politics divergence between Russia and Ukraine gradually strained the relationship between the two countries. The harder Russia tried to reinvent a new supranational arrangement that would keep the two countries together geopolitically, the more Ukraine resisted and tried to break free. As Russia’s methods of pressure escalated, so did Ukraine’s commitment to a Euro-Atlantic foreign policy. And, as the confrontation between the former vassal and the wannabe suzerain intensified, the Russia–West relationship soured as Russia accused the West of trying to lure away Ukraine. Meanwhile, the West attempted to strike a balance between accommodating Russia’s concerns and helping Ukraine democratize and pursue the European integration path it had chosen. 2013 to 2014 would become a fork in the road for all three.

The fork in the road was the Euromaidan revolution, which opens Chapter 5. The popular uprising, known in Ukraine as the Revolution of Dignity, was triggered by Yanukovych’s last-minute attempt to reorient Ukraine away from the EU and toward Russia, but was sustained by fears of the regime’s growing autocratization and radicalized by the violent attempted suppression of the protest. After Euromaidan culminated in Yanukovych’s ouster, Russia lashed out against the new Ukrainian government, intervened and annexed Crimea, and spurred and backed an anti-Kyiv insurgency in Donbas. The chapter traces the momentous events of 2013 to 2014 and analyzes Russia’s goals in launching military aggression against its neighbor. We argue that, paradoxically, the Donbas war was not really about Donbas. Rather, by helping to jump-start and by supporting the separatist proxy statelets of Donetsk and Luhansk “people’s republics,” Russia was planning to use Donbas as a tool to bring about the vassalization of all of Ukraine. The Minsk peace accords were a Trojan horse that Russia sought to use to keep control of Ukraine. Russia wanted the proxy republics it controlled to get a de-facto veto power over policies of the central government through the Minsk accords.

Chapter 6 analyzes the consequences of Euromaidan, Crimea’s annexation, and the war in Donbas. 2014 was a watershed moment in Ukraine’s political trajectory, but not in the way Putin calculated. All the processes he aimed to reverse – Ukrainian identity consolidation, democratization, and a pro-European foreign-policy orientation – accelerated like never before. Rather than turning on each other, Ukrainians leaned into their independent statehood and distinctive identity. Rather than falling into political instability and dysfunction, Ukraine accelerated political reforms and made progress in democratic consolidation, the rule of law and anti-corruption reforms, and growing state capacity. Instead of accepting destiny as a Russian vassal, Ukraine’s government and society looked toward Europe and the West with increased enthusiasm and ambition. Instead of acknowledging that its own actions were pushing Ukraine further away, the Putin regime doubled down on the narrative of Western meddling in Ukraine. As the Minsk process failed to deliver a paralyzed and vassalized Ukraine, Putin eventually decided to escalate to the full-scale invasion of 2022.

The concluding chapter recaps the 2022 to 2023 war and illustrates that the invasion was another step in the escalatory cycle, one which has turbo-charged the divergence between Ukraine and Russia. The two countries are now decisively disentangled and Ukraine wants to win the war and complete its geopolitical, economic, and cultural rupture from Russia. The chapter also asks what lessons we can draw from the war for the broader security of Europe and the world, and argues that the West should not return to pre-war cooperation with Russia and the dominant pre-war Western vision of Ukraine as a buffer zone between the West and Russia. Those who argue that Russia is too big and important to be isolated are wrong. Stable peace in Europe requires the realization that as long as Russia remains governed by an autocrat and wedded to an imperialist reading of its history and its destiny, it will remain a threat to its neighbors and to European and global security and stability. Russia should be contained for as long as it takes for Russian society to bring about regime change and democratization. Ukraine should be integrated into the West through EU accession and NATO membership.

Notes

1

President Putin’s address on Ukraine, February 24, 2022.

http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/statements/67843

2

Washington Post

, February 21, 2022.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2022/02/21/ukraine-invasion-putin-goals-what-expect

3

President Zelensky’s address, February 26, 2022.

https://www.nbcnews.com/video/president-zelenskyy-sends-video-to-ukrainian-people-134108741773

4

Newsweek, May 23, 2023.

https://www.newsweek.com/russia-death-toll-ukraine-already-same-10-years-afghanistan-1708991

5

Sergei Glazyev quoted in D’Anieri, 2019, p. 200.

6

Rating Group poll, February 17, 2022.

https://ratinggroup.ua/research/ukraine/dinamika_vneshnepoliticheskih_orientaciy_16-17_fevralya_2022.html

, pp. 4–5.

7

Rating Group poll, February 16, 2022.

https://ratinggroup.ua/research/ukraine/obschestvenno-politicheskie_nastroeniya_naseleniya_12-13_fevralya_2022.html

, p. 9.

1Entangled histories and identity debates

In his February 21, 2022 speech, days before announcing a “special military operation” in Ukraine, Putin listed his vision of Ukraine’s past, present, and future. He claimed that Ukraine is “an inalienable part” of Russia’s “own history, culture and spiritual space.” “Since time immemorial, the people living in the southwest of what has historically been Russian land have called themselves Russians … Modern Ukraine was entirely created by Russia or, to be more precise, by Bolshevik, Communist Russia.”1 This theme of Ukrainians being “really” an organic part of a Russian pan-nation and an independent Ukrainian state being an artificial construct existing at the expense of “historical” Russia, or at the pleasure of contemporary Russia, is at the core of the current war. It has been a central tenet of Russia’s intellectual thinking even if it has not always driven post-Soviet Russia’s state policies. Ukraine and Russia’s entangled histories can be told through competing interpretations. One version presents historical events as justifications for “organic unity,” thus trying to strengthen modern-day contentions that Ukraine and Russia have always been destined to be together. An alternative view emphasizes evidence of Ukraine and Russia’s distinctions going back centuries, and Russia’s repeated attempts to suppress independent Ukrainian identity and crush Ukraine’s quest for political autonomy and its own state.

In the post-Soviet period, interpretations of history informed debates over national identity in both states. What were the “true” Russian and Ukrainian nations? Competing views of shared history came to inform alternative nation-building projects, which offered different answers to this question. In post-Soviet Russia, several intellectual constructs of a “true” Russian nation have co-existed, but only one of these intellectual imaginaries is compatible with the notion that Ukraine is a distinct nation and a legitimate independent polity. Later in this chapter we discuss how, by the middle of the 1990s, multiple factors prevented this option from becoming a guide to Russian state policies. Instead, Russian identity progressively imperialized, as the Russian state embraced the idea of Russia as a supra-national civilization, which included Ukraine.

In Ukraine, there were also competing intellectual constructs of a “true” Ukrainian nation but, already in the late perestroika period, identity politics resulted in state elites embracing a conception of national identity that underscored Ukraine’s distinctiveness from Russia. Over time, the Ukrainian state’s commitment to this identity option only strengthened, increasingly coming into tension with the re-imperialization of identity in Russia, both reinforcing each other in an escalatory cycle. The Yanukovych presidency in 2010 to 2014 was the period when the escalatory cycle could have been halted and potentially even reversed, but this option was foreclosed by Yanukovych’s ouster. In subsequent years, divergence accelerated – this post-2014 divergence will be discussed in greater detail in Chapter 6. Battles over identity were not the only cause of Russia’s 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine, but the war cannot be fully understood without the escalatory cycle generated by diverging identity projects in the two states informed by divergent interpretations of history.