Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: el!es-Verlag

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

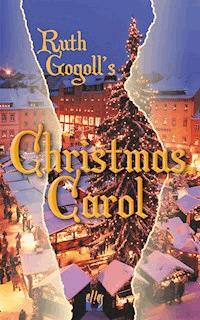

Ruth Gogoll's Christmas Carol is a new twist on an old classic. Christmas is coming and goodwill and merriment fill the town. It's not the best of times for everyone however ... Company president Michaela Wittling is all work and no play and Christmas is just another day. What's all the fuss about? The lights are a waste of electricity. They all expect time off and bonuses. Humbug! Faithful employee Ramona Benckhoff is all worry and no play. Will I keep my job? Will the boss find out I sometimes cut my hours short to go to the hospital? And, the most frightening question of them all ... Will my daughter live to see the New Year? Michaela thinks she has it all figured out. Ramona believes she has no hope and nothing figured out. One very strange night changes everything.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 181

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Ruth Gogoll’s

CHRISTMAS CAROL

Translated from the German by

© 2010édition el!es

www.elles-books.com [email protected]

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book, or portions thereof, in any form whatsoever.

ISBN 978-3-95609-177-3

Cover photo shows the Christmas market in Annaberg-Buchholz, Germany © Pixstore – Fotolia.com

“Leave me alone. I don’t want anything to do with bloody Christmas!” Just the thought of the upcoming holiday got Michaela’s blood boiling.

“Ms. Wittling, you can’t ignore it any longer, we have to talk about it now.” Her secretary, a calm and composed woman in her mid-fifties, was unwavering. Those many years working for the Wittlings had taught her perseverance. “Your employees are entitled to a few days off. Have you thought about the holiday bonus yet?” She raised a questioning eyebrow.

“What? Days off? A bonus?” Michaela asked, getting more and more agitated. “They are off all the time anyway; that alone costs a fortune! Now you want me to give them a bonus? For what? A Christmas bonus so they can go and spend money on gifts? Go shopping in their free time while I’m working? Nobody is giving me any gifts, why should I give them?”

“We’re not talking about gifts,” her secretary reminded her patiently. “Your employees are legally entitled to it all.”

Michaela Wittling, Mike to some and only on special occasions, rose to her imposing six feet two inches. Her dark hair fell into her face and made her look even more menacing. “Bad enough,” she said, “that the government is supporting this kind of extravagance and idleness.”

“May I . . .?” A blond woman of slight build stepped over the threshold of Michaela’s office and stopped.

“What?” Michaela barked at her as if this one employee was responsible for the misery she was facing at that moment.

“I’m sorry, I . . . please forgive me; I did not mean to interrupt.” The young woman began to withdraw.

“Come on, spit it out already.” Michaela drummed her fingers impatiently on the desk. “I can’t stand this kind of submissive behavior. Just tell me what you want!”

“I . . . I heard that the company won’t be closing over the holidays, that we are allowed to come and work. I thought . . . well, I mean . . . if it’s possible . . . I would like to take the opportunity and catch up on a few things and finish them before the end of the fiscal year.”

Michaela was stunned for a moment. Surprised, she raised her eyebrows, but quickly drew them together again. “Because of the double time, right? You let the work add up until it’s too late, and then you’ll be getting paid double because you’re working on a holiday.”

“No . . .” The young woman slowly raised a hand as if to ward off a bad spirit. “No, that’s not how it is. I just noticed last year . . . it’s simply not feasible to get the work done before the holidays. There are always so many orders coming in at that time. The balancing of the books gets delayed. That leads to trouble with the Tax Office. Then we’ll have to pay fines, which we could avoid if I work over the holidays. That way I could submit the annual balance sheets on time. I . . . I don’t even want to be paid any double time.” Her eyes had been searching the floor while she had spoken. Now she lifted them and looked up at Michaela, as if she were asking for approval of an outrageously audacious suggestion. “I just want everything to be correct and on time.”

“You are entitled to double time, Ramona; you can’t waive it,” Michaela’s secretary commented. “And I, for one, like your idea. We would save much more than we’d have to pay you extra,” she said with a sly sideways glance at Michaela.

Michaela sat down, still drumming her fingers on the desk, though much less impatiently and intensely as before. “Is that correct?” She looked at her secretary. “We would save something?”

“That’s right,” her secretary confirmed, nodding her head. “But, don’t you need to be with your daughter?” she asked Ramona. “Will she not miss her mother on Christmas Eve? She’s still quite small, isn’t she?”

“She –” Ramona started to sway. “She will have to be in the hospital over Christmas.”

“Over Christmas?” The secretary’s voice sounded appalled.

“There’s no other way, she – it’s a difficult treatment.” Ramona looked at the floor again. She was shaking so hard by now, she was wishing for a chair.

“All right,” Michaela said. She did not seem to have listened to that last exchange. “You’ll be working over Christmas. I will be here, too, as always.” She dismissed Ramona with an impatient wave of her hand.

“Would you have time now to speak with the representatives from the children’s charity?” Mrs. Majakowski poked her head through the door to Michaela’s office.

“Children’s charity?” Michaela frowned. “What is that supposed to be?”

“A charitable organization that helps children.” Mrs. Majakowski opened the door wide. “Please come in. Ms. Wittling has time for you now.”

“I don’t have –!” Michaela jumped up from behind her desk, but Evelyn Majakowski was already gone, and in her place two bundled-up people were standing in the room, a woman and a man.

The man approached Michaela with an outstretched hand. “Ms. Wittling. I’m pleased to finally meet you in person.”

I can’t say the same, Michaela thought, accepting the handshake only reluctantly.

The older woman loosened her scarf and opened the top button of her coat before she, too, extended her hand in greeting. “I can still remember your father – and your grandfather,” she said with a smile. “It was always a joy to meet with him. He gave from his heart.”

“Oh, that’s what it’s about.” Michaela sat down. “You want a donation.”

“There was a tradition in the Wittling Company to –”

“When my grandfather was still running the company – and my father,” Michaela interrupted the man. “I have not subscribed to this tradition.”

“It’s Christmas . . .”

“Oh, is it already?” Michaela swiveled around in her chair and looked at the big wall calendar, a present from one of their suppliers. “I hadn’t noticed. Times never change for me. All days are the same.”

“But, Christmas . . .” the man stammered.

“It’s not possible to miss out on Christmas, you mean?” Michaela gave the man an ironic smile that did not reach her eyes. “You are absolutely right. It’s an unfathomable extravagance. Everything is brightly illuminated, day and night. I don’t want to know the cost of all of that.”

“Christmas is only once a year.” The older woman tried to support her colleague. “And it’s the most important holiday of all, particularly for children. We try to bring joy to those children whose parents can’t afford to give them presents or those who don’t even have parents anymore. Many companies donate something from their own product lines –”

Michaela’s laugh sounded almost sincere. “Wine and liquor! Those are my product lines. Hopefully you don’t want to suggest I donate some of that to the children?”

“No, no.” The woman smiled. “That would not be appropriate, of course.”

“Well, there you are.” Michaela got up from her chair. “I can’t really donate anything. That would be that then.”

“But –” The man and the woman were perplexed. The woman was the first to regain her composure. “Your grandfather always –”

“I know what my grandfather did.” Michaela raised a hand. “But I can’t afford those kinds of expenses. Under my grandfather, the business flourished and the profits were good. Today, however, there’s hardly any profit to be made. Taxes, fees, personnel expenses, declining sales figures, you are probably aware of the current economic situation. I have to be glad I can afford to run the business.”

“Donations are tax deductible.” The man sounded desperate now.

“That doesn’t mean they will be reimbursed. They only lower the profit. And, if there is no profit, it can’t be lowered. So there would be no tax benefit.”

The two charity representatives were stunned into silence.

“And, by the way,” Michaela continued, “whatever happened to good old public welfare?”

“Social welfare, you mean,” the man squeezed out the words through white lips.

“Yes, that’s what I mean. Isn’t that what’s driving our country into ruins? Too much social spending? So, everybody is taken care of nicely, it seems.”

“It’s about the children,” the woman said in a pleading tone. “The poorest of the poor. There are also many people who are too proud to accept welfare. And then it’s again the children who suffer. They can’t apply for it themselves, you know.”

“Then they should start learning to,” Michaela said. “Or wait until they earn their own money.”

“If they’ll still be able to by then,” the man said. He put on his gloves. “Come on, Linda, it’s no use. I wouldn’t even have come, but you always said that old Wittling –”

“That old Mr. Wittling was a generous man, a great person,” the woman replied. “That’s what I remembered. I had forgotten that’s not necessarily been passed onto the next generation.”

They left the room without attempting to shake Michaela’s hand once more.

After a few minutes, Evelyn Majakowski entered the office. “You didn’t give anything?”

Michaela had already forgotten about her visitors. “What? Oh, right.” She looked up from her papers. “As far as I know, I wouldn’t get anything for donating something. What would be my return on investment?”

“Peace of mind,” Evelyn Majakowski said.

“Peace of mind?” Michaela raised an amused eyebrow. “My mind – and the rest of me – is at peace, don’t you worry. I sleep very well at night.”

“That surprises me,” Evelyn Majakowski commented. She sighed.

She usually did not justify her actions, but Michaela felt the need to explain her reasoning to the woman who had known her since childhood. “You knew my father,” she said. “You know what a squanderer he was. He ruined the company. I have inherited the extravagance of both my parents. That’s why I have to be careful. I could end up like them.”

“I don’t believe that for one moment, Michaela.” Evelyn Majakowski had not used Michaela’s first name in a long time; she sounded highly skeptical. “I don’t think you are susceptible to excess. If you were, you’d have shown signs of it by now.”

“My father’s compulsive gambling runs through my blood,” Michaela said. “I noticed it once. I’ve never gambled since, and I won’t ever again.”

“That only proves me right,” Evelyn Majakowski said and smiled. “You don’t need to be afraid. Your father had no self-control, but you do. You are not your father.” She gave Michaela a stern look. “Maybe your self-control is too rigid at times. Stinginess can be just as compulsive as extravagance.”

“I’d rather be stingy than wasteful,” Michaela retorted defiantly.

“You won’t go bankrupt if you allocate the money sensibly, including donations,” Evelyn countered. “What you give to others will come back to you a thousand fold.”

Michaela shook her head in disagreement. “I had no idea you were such an idealist, Mrs. Majakowski.”

“When you were a child, Ms. Wittling,” Evelyn returned to the formal address, “didn’t you like to celebrate Christmas, sitting by the Christmas tree and enjoying your presents?”

“I can barely remember that time,” Michaela growled.

“But you do,” her secretary insisted. “And now? Don’t you think you would enjoy sitting by the tree again with somebody and not just being there by yourself?”

“I don’t have a Christmas tree,” Michaela grumbled.

“Maybe you would have one then,” her secretary replied dryly.

“I have no idea what you are trying to say – and I don’t even want to know!” Michaela got impatient now.

“You know exactly what I mean. It’s not good to be alone. That’s even in the bible.” It took all of Evelyn’s energy to stay calm. Michaela was really behaving like a little child.

“Another one of those superfluous things!” Michaela looked at Evelyn. “Now, is that all?” She wanted to get rid of Evelyn as fast as possible. It was starting to get to her. First those beggars and now her secretary. She had a lot of work to do, and everybody was keeping her from it with these discussions.

“It’s late already,” Evelyn said, as if to hint at something. But Michaela didn’t catch on. “It’s Christmas Eve. We are the only ones still here. Everybody else has left; though, Ms. Benckhoff is coming back later. You know, she’s going to finish the year-end accounting.”

Michaela nodded, clearly not listening to her. She just wanted to be left alone.

Evelyn Majakowski sighed deeply. “Merry Christmas, Michaela,” she said in a soft voice and closed the door behind her.

“Can I go home with you, Mommy?” Leonie asked, her eyes shining.

Ramona was sitting at Leonie’s hospital bed and almost started to cry when she heard these words.

“I want to go home for Christmas.”

Ramona swallowed. She could not show her daughter how she was feeling. She tried to smile. “Not this year, sweetheart,” she said. “You see the IV and all that? It would be much too difficult to take that home. Our apartment is too small. There’s not enough room for all of it.”

Leonie made a face. “Do we have to take all of it with us? Can’t we just leave it here?”

Ramona tried to decide if she should lie to her daughter or tell her the truth. Maybe it would be better if she knew – but she was still so young. How was she supposed to understand this? “No, we can’t,” she said quietly and smiled. “You need it all, so you won’t feel bad again, like a few days ago. You don’t want to feel bad, do you?” She carefully brushed the hair from her daughter’s forehead. “But when you feel better, you’ll come home, and we’ll celebrate Christmas then, for sure.”

“Promise?”

“Promise.” Ramona struggled to keep her composure. She felt like collapsing on the bed and giving in to her tears. “I have to go now,” she said. “To work. I’ll be back tomorrow. You’ll probably be up and running around by then and teasing Florian.”

“He teases me!” Leonie’s little face was haggard, showing signs of fever, but she still had enough energy to protest.

“Of course. He teases you.” Ramona put on her most confident smile. She bent down and kissed her daughter’s cheeks, which were gleaming and wet with sweat.

When she stepped out into the corridor, she steadied herself against the wall. Then she slowly straightened. Maybe it was good after all that she could go to work now. She would not have to think of Leonie constantly, of what was lying ahead for her. For a few seconds, she would not see her little face in front of her, how she got smaller and smaller, weaker and weaker.

“Ms. Wittling? Would you have a moment for me?”

Michaela’s head snapped up. She had completely forgotten that there was somebody else in the office, despite Mrs. Majakowski’s announcement. “Yes?”

Ramona entered the dark room. There was only a small desk lamp that illuminated a tiny part of Michaela’s desktop. Even here she’s saving, Ramona thought. “I have a question about the accounts. Usually I wouldn’t bother you with it, but –”

“Get on with it!” Michaela was already growing impatient again. “What is it?”

“This receipt . . .” Ramona walked over to Michaela’s desk and tried to hold the paper into the tiny beam of Michaela’s lamp. “It’s simply wrong. I checked the warehouse. We had ordered one hundred bottles of champagne, and that’s also what the invoice says. But they only delivered ten bottles.”

“Beg your pardon?” Michaela stared at her.

“Yes, it’s true,” Ramona confirmed.

“Has the invoice been paid yet?” Michaela now stared at the piece of paper.

“Yes, unfortunately. Apparently, nobody made the effort to look. When the delivery came, the number was just checked off.”

“Ten instead of one hundred?” Michaela could not fathom it.

“Yes. To be honest, I don’t understand it either. But we definitely got only ten bottles, that’s for sure.”

“This is the most expensive champagne we have,” Michaela said.

“Yes,” Ramona confirmed again. One bottle cost more than she earned in a month – in several months.

Michaela got up and started pacing the room. “I don’t believe that was an accident,” she mumbled to herself.

“You think somebody stole them?”

“What? Yes.” Michaela answered absentmindedly. She had already forgotten that Ramona was in the room. “I’ll get to the bottom of this,” she said through clenched teeth. She sat down. “Thank you very much for pointing it out to me. Have you found any more irregularities?”

“None so far,” Ramona said. “It’s the first time I noticed something like this. But I’m not through with everything.”

“OK.” Michaela bent low over her desk to be able to use the small light source.

“Oh, Ms. Wittling?”

Michaela looked up with an irritated expression. She could hardly see Ramona in the dark of the room. “What is it?”

“I . . . I wanted to apologize for coming so late. I was at the hospital.”

“At the hospital? Are you sick?” Michaela’s questions sounded indifferent.

“No, I’m not. But my daughter.”

Michaela nodded automatically. “She’ll get better,” she stated, uninterested. “Children often have something.”

Ramona felt the tears stinging in her eyes. “My daughter is dying, Ms. Wittling,” she replied with a wavering voice, “and there’s nothing I can do about it.” Then she hurried out of the room.

A short time later Michaela heard the heavy front door falling closed.

It was late when Michaela headed home that evening. The streets were deserted. She entered her apartment where everything looked exactly as it always did. There were no Christmas decorations, no burning candles. Michaela missed none of it. What was all that humbug for anyway?

The apartment had only sparse furnishing; there was nothing unnecessary. Michaela’s idea of superfluous included a coffee machine, a refrigerator and a television. She had none of those.

She had moved into the apartment with the few pieces of furniture remaining from the previous tenant. She had been forced to sell her family’s house after she had inherited the company and discovered that she was nearly bankrupt. Her father had needed only a few months to ruin what had taken her grandfather decades and a lot of effort to build. At that moment, she had taken a solemn oath never to become like her father. Yes, he had always been everybody’s darling. However, Michaela was not after that. Popularity had no value. Money was the only thing that counted, never having to rely on anybody.

She crossed her apartment in the weak light streaming through the window from a street lamp. Why should she turn on a light? She knew where everything was. There was hardly any furniture, so there was not much opportunity to run into anything. She did not have to pay for the street lamp – although, that was not entirely true either, her taxes paid for it, much to her annoyance.

She just wanted to change out of her clothes, brush her teeth and fall into her bed. She had no use for Christmas. She did not notice that the light through the window seemed to be brighter that night because the street lamp was supported by the many colored lights shining out from the surrounding windows. Had she noticed, she would not have cared. At worst, she would have gotten upset about people’s wastefulness. Those people somehow felt the need to illuminate the street, which was a waste if they were inside.

She yawned and went to bed, shivering when her body hit the cold sheets. There was no heat in her bedroom. It would get warm under the blanket in a moment, as always. She was still waiting for all of her toes to adjust to the surrounding temperature when she started to drift off.

She had a strange dream. What was even stranger: She usually did not dream at all. While she was dreaming, she was not aware of that, of course.

She was running through a long corridor, searching for something, though she would not have been able to say what exactly she was looking for. She opened every door, of which there were incredibly many on the seemingly endless corridor, and looked inside. She found herself in front of storage rooms, bricked-up doors and windows, never finding what she was searching for. Once there seemed to be a room flooded with light behind one door, but when she wanted to look inside to see what kind of room it was, the door closed, and she was back in the dimly lit corridor. She noticed she was starting to panic. She knew, she had to find it . . . it . . . it . . . whatever it was.

“Mike . . . Mike . . .” A voice drifted through her dream. “Mike . . .”

She opened her eyes and peered into the darkness. Her bedroom faced the courtyard; not even the street lamps could cast a glow here. Still, her eyes adjusted quickly to the absence of light, and it was as if shadows populated the room, formless, faceless shadows.

“Mike . . .”

It sounded like an echo, a faraway echo without any substance, as if coming from nowhere, as if it had no origin.