27,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Newly published for the first time in English translation, Carl Schmitt’s 1934 tract, State Composition and Collapse of the Second Reich: The Victory of the Bourgeois Citizen over the Soldier, is an important addition to the corpus of Schmitt’s work in English. Written and published at the height of Carl Schmitt's entanglement with National Socialism, this work outlines Schmitt’s historical and propagandistic account of the collapse of the Second German Empire and of Germany’s defeat in the First World War and sets the stage for his account of what should come next.

In this swiftly paced polemical history, Schmitt locates the roots of Germany’s defeat in the First World War in constitutional compromises between the Prussian soldier state and the liberal bourgeois citizenry forged in the course of the nineteenth century. These compromises left unresolved the tension between liberal constitutionalism and an executive-led strong state built on military power, preventing the Reich from being able to mobilize German society in order to wage a successful war effort. Schmitt’s account of how the Bismarckian Reich was undermined from within serves as a guide, in his view, for how the Nazi regime should avoid a similar fate.

A work of crisply riveting and, at times, haunting prose, Schmitt’s State Composition and Collapse of the Second Reich will be a source of persistent historical interest to all students of history, politics, Nazism, political thought and the First and Second World Wars.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 177

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Editor’s Note and Acknowledgments

Foreword

Notes

State Composition and Collapse of the Second Reich

I. Prussian Soldier State and Bourgeois Civil Constitutionalism

1. The insoluble conflict between soldierly Führer-state and bourgeois rule-of-law state

2. The soldier state spiritually on the defensive

3. The Plea for Indemnity

4. The People [Volk] without political leadership [Führung]

5. The State without Government

Notes

II. The Collapse

1. Unfolding of the internal state cleft in the World War

2. The three constitutional-historical days: 5 August 1866, 4 August 1914, 28 October 1918

3. The Weimar Constitution as posthumous victory of the liberal bourgeois citizen over the German soldier

4. The Reichswehr in the Weimar Party-state and the Prussian coup [Preußenschlag] of 20 July 1932

Conclusion

Notes

Appendix: Carl Schmitt, “The Logic of Spiritual Subjection” (1934)

Notes

Bibliography

Index

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Editor’s Note and Acknowledgments

Foreword

Begin Reading

Appendix: Carl Schmitt, “The Logic of Spiritual Subjection” (1934)

Bibliography

Index

End User License Agreement

Pages

iii

iv

vi

vii

viii

ix

x

xi

xii

xiii

xiv

xv

xvi

xvii

xviii

1

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

State Composition and Collapse of the Second Reich

The Victory of the Bourgeois Citizen over the Soldier

Carl Schmitt

Edited and translated by Samuel Garrett Zeitlin

Foreword by Reinhard Mehring

polity

Originally published in German as Staatsgefüge und Zusammenbruch des zweiten Reiches. Der Sieg des Bürgers über den Soldaten. Copyright © 2011 Duncker & Humblot GmbH, Berlin. “Staatsgefüge und Zusammenbruch des zweiten Reiches” was first published in 1934 by the Hanseatischen Verlagsanstalt, Hamburg. “Die Logik der geistigen Unterwerfung” was first published in Deutsches Volkstum, 1 3. 1934, pp. 177–182.

This English translation © Polity Press, 2026

Polity Press65 Bridge StreetCambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press111 River StreetHoboken, NJ 07030, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-6625-9

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2025941012

The publisher has used its best endeavors to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website:politybooks.com

Editor’s Note and Acknowledgments

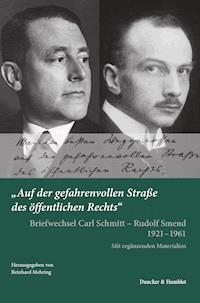

Writing in the Historische Zeitschrift in 2005, the German historian Dirk Blasius noted that “In the capacious Schmitt literature his treatise on the collapse of the Kaiserreich hardly receives any attention.”1 Several decades later, Blasius’s judgment might be reiterated almost unaltered. Nonetheless, the present edition and translation have benefited substantially from Blasius’s studies,2 as well as the studies of Joshua Smeltzer, Lars Vinx, Günter Maschke, and Reinhard Mehring. It is thus fitting that this edition opens with a foreword by Professor Mehring.

This translation of Carl Schmitt’s State Composition and Collapse of the Second Reich aims to produce as accurate a translation of Schmitt’s German history within the limits of English readability, preserving Schmitt’s paragraphing and sentence structure, the precision of Schmitt’s political vocabulary, as well as the rhythm and tone of Schmitt’s prose. The German term Bürger, present in Schmitt’s subtitle and thematized throughout the book, does not distinguish between bourgeois and citizen, and for this reason Bürger is rendered throughout as “bourgeois citizen.” A critic may argue that by “Bürger,” Schmitt means “bourgeois” – which is not false. Yet, as Schmitt would go on to defend the Nuremberg Laws in 1935 (the year immediately after the publication of this book) and to persistently defend stripping Jews of their civic and citizenship rights in Germany (and in Nazioccupied and allied lands), the concatenation of bourgeois and citizen within the term Bürger should not be effaced. Within Schmitt’s political arguments from the 1930s, the soldier should triumph over the bourgeois, and a particular subset of those whom Schmitt inscribes as “bourgeois” are, from Schmitt’s advocacy, to be stripped of citizenship and civic rights.3

The edition and translation was made on the basis of Günter Maschke’s edition of Schmitt’s German text (Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 2011) checked against Schmitt’s 1934 German original (Hamburg: Hanseatische Verlagsanstalt, 1934). Within the edition, Schmitt’s own notes to the main text of State Composition and the Appendix are footnotes to the main body of the text in Arabic numerals whilst the notes to the Foreword and the editorial notes are endnotes marked with Roman numerals.

For the chance to prepare this edition and translation for Polity, I am thankful to John Thompson and to Elise Heslinga and Evie Deavall, and to conversations with Susan Neiman.

Clara Maier and Martin Ruehl generously read the entire translation through and saved it from numerous errors. Those that remain are those of the translator.

At University College London, I am thankful for my colleagues in its storied department of History, Valentina Arena, Margot Finn, Alex Goodall, Angus Gowland, Fabian Krautwald, Patrick Lantschner, Sophie Page, Jason Peacey, Benedetta Rossi, John Sabapathy, Peter Schröder, Antonio Sennis, Julietta Steinhauer, Iain Stewart, and Florence Sutcliffe-Braithwaite. At the Institute for Historical Research, I am grateful for the chance to co-convene the “History of Political Ideas” seminar with Callum Barrell, Hannah Dawson, Andrew Fitzmaurice, Niall O’Flaherty, Angus Gowland, Dina Gusejnova, Humeira Iqtidar, Gareth Stedman Jones, Julia Nichols, Paul Sagar, Quentin Skinner, and Georgios Varouxakis.

Not least, I am thankful for the love of my family – to my sister, Ellie, my mother, Elizabeth, and my partner, Joanna.

The work of this translation is dedicated to Professors Valentina Arena, Angus Gowland, and Peter Schröder, with gratitude and intellectual esteem for their scholarship.

Samuel Garrett Zeitlin University College London

London, 17 April 2025

1.

Dirk Blasius, “Carl Schmitt und der ‘Heereskonflikt’ des Dritten Reiches,”

Historische Zeitschrift

281 (2005), pp. 659–682, at p. 678: “In der umfangreichen Schmitt-Literatur findet seine Abhandlung über den Zusammenbruch des Kaiserreichs kaum Beachtung.”

2.

Ibid. See also Dirk Blasius,

Carl Schmitt: Preußischer Staatsrat in Hitlers Reich

(Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2001).

3.

See Carl Schmitt, “Die Verfassung der Freiheit,”

Deutsche Juristen-Zeitung

40, no. 19 (1 October), Sp. 1133–1135, reprinted in Carl Schmitt,

Gesammelte Schriften 1933–1936

(Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 2021), pp. 282–284. For Schmitt’s defenses of the Vichy revocation of the Crémieux Decree in 1940, stripping Algerian Jews of their French citizenship, see Carl Schmitt, “The Forming of the French Spirit via the Legists,” in Carl Schmitt,

The Tyranny of Values and Other Texts

, ed. Russell A. Berman and Samuel Garrett Zeitlin (Candor, NY: Telos Press, 2018), pp. 51–90.

“Spiritual Subjection”? On the “Tragic” Tone of Schmitt’s TextA Foreword to State Composition and the Collapse of the Second Reich

Reinhard Mehring

Schmitt’s tight polemical text from early in the year 1934 is manifestly contemporary. Indeed, the questions concerning the relation between army and state, political constitution and military constitution, pose themselves anew after the “return of war” to Europe, in the Near East, and other regions of the world today, where the United States reorients itself toward a runoff with China and takes its distance from the “trans-Atlantic West.” Everywhere in Europe, the European Union as well as NATO must newly adjust the mentality and constitution of state and society to military threats. Though it may sound odd, dissonant, crazy, or improbable, might a calculated National Socialist programmatic text by Carl Schmitt here be capable of stirring contemporary thought? Its critical questions concerning the “parliamentary army,” “budgetary right,” military service, and the constitutional weakening of political leadership and “unity” are, in any event, posed again today.

The brochure stands in a row of polemical and programmatic texts, which Schmitt published in swift succession after his decision for National Socialism: after the so-called Enabling Act (Ermächtigungsgesetz) of 24 March 1933, up until the summer of 1934 alongside a plethora of lectures, articles, and journal pieces.i If Schmitt was not only an opportunist and careerist, but rather a political author, constitutional theorist, and “thinker of order” who also disposed of fundamental answers and formational proposals, then this must show itself precisely in the programmatic brochures. As “crown jurist,” Schmitt was already controversial in 1934: in April 1933, Schmitt, though not yet a member of the Nazi Party, was already participating as a legal-technical counselor in the formulation of the Reich Governors’ Law (Reichstatthaltergesetz) for bringing the German states into line with Nazi policy, already lost in the course of the year 1933 as “state counsel” contact to Hermann Göring, and had to set himself more upon the Reichsrechtsführer Hans Frank, who did not belong among the first guard and the innermost circle with Hitler.

Schmitt’s first programmatic text for the formation of the National Socialist Führer-state – State, Movement, People – remained extremely vague and recommended, according to the model of Göring’s “state counsel,” in terms of concrete constitutional politics little more than the erection of a “Führer’s counsel” in parallel or as an alternative to the transmitted executive cabinet system; Hitler, however, persisted with the state and the Party. Up until the summer of 1934, Schmitt now wrote, from January 1934 onward, his brochures On the Three Types of Juristic Thinking, StateComposition and Collapse as well as National Socialism and International Law, which all grew out of lectures. Up until 30 June 1934 and the liquidation of the heads of the Sturmabteilung (SA), as well as one-time opponents of Hitler, with a portion of whom Schmitt was personally as well as politically connected; Schmitt then reacted with a ground-shaking alteration of perspective and of strategy, which he immediately signaled multivalently in a highly contested article, Der Führer schützt das Recht [The Führer Protects the Law]. Schmitt’s hope for a constitutional capacity of National Socialism, and his exertions (in Schmitt’s terminology) to elevate a state of exception into the normal condition of a strong “Führer-state,” had failed. From then on, Schmitt saw himself again within the state of exception, viewing National Socialism as the Leviathan, and for further political-theological legitimation, grasped strengthened in the semantic arsenal of anti-Semitism and of apocalypticism.

State Composition and Collapse of the Second Reich is Schmitt’s most thoroughgoing attempt to define the relation between state and movement of Hitler’s “legal revolution.” The text proceeds from a lecture on “Army Order and Complete Political Structure” [“Heerwesen und politische Gesamtstruktur”], which Schmitt held on 24 January in the aula of the Berlin University, repeated on 13 February at the urgent request of his fellow-traveler Carl Bilfingerii in Halle, and which Schmitt promptly published in an abbreviated version under the title The Logic of Spiritual Subjection in the journal Deutsches Volkstum. Schmitt then rebuilt the text after the completion of Three Types of Juristic Thinking into the brochure. In his diary, Schmitt noted on 17 April, that, in the train en route “to Ernst Jünger and my godson” from Berlin to Goslar, he brought the manuscript “into order.”iii

Since 1930, Schmitt was closely befriended with Ernst Jünger (1895–1998), a highly decorated war hero of the First World War, epitome of the idealized “Soldier.” Jünger was an opponent of the Weimar Republic as well as of National Socialism. After a search raid on his house, Jünger withdrew from the firing line of Berlin to Goslar in December 1933. Despite the still-contrary assessment of National Socialism at the time, Jünger invited Schmittiv to assume the godfathership of his second son Carl Alexander, whom Schmitt called a “new Earth soldier” in a congratulatory letter dated to 15 March 1934.v The Hüter der Verfassung [Guardian of the Constitution] had approvingly cited Jünger’s “total mobilization”; State Composition and Collapse repeats this.vi In 1932, Jünger published his famous essay, Der Arbeiter: Herrschaft und Gestalt [The Worker: Rule and Figure],vii to which Schmitt responded with his discourse of the “Victory of the Bourgeois Citizen over the Soldier.” State Composition and Collapse speaks without Jünger’s stately confidence rather resignedly of an “opposition of human types”: “education and possession against blood and soil,” and of strife “concerning the figuration of the German himself.”

The brochured series edited by Schmitt, Der Deutsche Staat der Gegenwart [The Contemporary German State], in which Schmitt’s programmatic texts appear as volumes 1 and 6, Ernst Rudolf Huber published as volume 2, at that time the economic-legal sketch Die Gestalt des deutschen Sozialismus [The Figuration of German Socialism]. In a letter dated to 1 May 1934 addressed to Huber, Schmitt mentions a “difference of opinion concerning the concept of figure,”viii which refers to a “very deep philosophic question.” By this, is perhaps meant the anthropological or characterological shaping force: whether military service or the industrial economy and factory shapes the “type” more. Schmitt does not assertively participate in the then-present controversies concerning philosophic anthropology, although he knew all the main participants – Max Scheler, Helmuth Plessner, Paul Ludwig Landsberg, Arnold Gehlen – closely; the Concept of the Political in particular approvingly referred to Plessner’s text Macht und menschliche Natur. Fundamentally, however, Schmitt, like Jünger, shunned disciplinary controversies. Constitution in the absolute sense, it is said at the outset of Constitutional Theory, means “the concrete way of being given by itself with every existing political unity.”ix It exists positively in the “self-assertion” of a political will, which, according to Schmitt’s Concept of the Political, shows itself also and precisely in the military self-assertion and in “readiness for death and killing.”x This will to political existence: distinction between friend and enemy, Schmitt finds missing in the German citizen, who, under the influence of “liberal thought,” no longer desires to be a soldier, but rather descends into the “bourgeois” and consumer. The questions were already posed by Oswald Spengler at the outset of the Weimar Republic in his text Preußentum und Sozialismus.xi Behind this stands Nietzsche’s question concerning the “Übermenschen” and the expressionistic search for the “new Menschen.” From Spengler to Jünger the questions were posed against the “left” labor movement and Marxism. Hitler and National Socialism saw themselves in this line.

Schmitt’s search for the constitution, type, and figure of a “strong” state is mostly discussed in scholarship from the vantage of the end and decline of the Weimar Republic and the role of the presidential system: often in the alternative Papen or Schleicher, although Schmitt sought proximity to both, while Brüning and the Catholic Center Party thoroughly ignored him. Here begin the riddles around the constitutional-political interpretation of Schmitt’s polemical text from 1934: instead of the decline of the Weimar Republic, it considers the “collapse of the Second Reich” and thus makes Bismarck and the Kaiserreich co-responsible for the “collapse.” Where, before the Leipzig State Court in the trial of Preußen contra Reich at the end of 1932, Schmitt had defended Papen’s Reich executive action against the Social Democratic government of Prussia (the striking down of a situation of civil war via a Reich executive action Schmitt had already experienced in 1919), Schmitt now plays the “soldier state” and “Prussian honor” against the “dualistic” structure of the late Wilhelmine era, which, early in the year 1934, could be understood as opting for the Reichswehr against a “second revolution” (by the SA), but also as a warning about polycratic developments and about the failure of the “One Party State”xii in the construction of unity.

Is it really an historian who is writing here? Does Schmitt not rather argue for the present with an historical parallel? Does he thus warn in 1934 of a possible “collapse” of the “Third Reich”? In any event, the text is not tuned by “victory” but more by “spiritual subjection” and “collapse.” Beyond the constitutional historical theses, fronts, and battles of 1934, the text in its pathos reads more like an historical drama or a tragedy of fate, for which, within Schmitt’s canon, Grabbe, Hebbel, and Kleist may perhaps be named. One could read out of this a fascistic “aestheticization of politics,”xiii as Walter Benjamin diagnosed it almost simultaneously in the case of Italian futurism, whilst Schmitt, like other anti-bourgeois extremists of the interwar period, was more literarily shaped by German expressionism (Däubler). Retrospectively, Schmitt swooned for the “tragic geniality of Hölderlin.”xiv

With his Concept of the Political, Schmitt personalized and polemicized the political event. He speaks of “betrayal” and “spiritual subjection,” “defensive” and “lost positions,” of an “heroic path” and “decline.”xv He declares the Minister of War to be a “tragic figure,”xvi and, indeed, even the Hitlerloyal Werner von Blomberg, Minister of War from 1933 to 1938, with whom Schmitt had spoken intensely “on the humanity of the soldier”xvii on 15 January 1934, was later dismissed under humiliating circumstances, to say nothing here of others like the Resistance of 20 July 1944. The “true causes of the catastrophe” Schmitt grounds in the “logic” of “spiritual subjection,” which he fixes particularly “like the development of an illness” on “pathognomic moments” and “instances.” The term of the “pathognomic moment” is, as a citation, placed in quotation marks without reference. What is meant is a set of symptoms without clear causes. Schmitt thus relativizes his pointed emphasis upon some decisions and withdraws them from intentional attribution and causal responsibility. Schmitt’s interpretations of Bismarck’s Indemnity Declaration have persistently irritated historians.xviii Schmitt, however, places it in a transpersonal “logic,” treats the Indemnity Declaration more as a didactic example and symptom, and speaks of a “solely coherent line of development” and of a “law,” which follows no natural causality, but rather an idealistic logic of “legal concepts”: “first the inner political spiritual subordination of the Prussian soldier state under the legal concepts of the bourgeois civil rule-of-law and constitutional state; then the subjection under the spiritual war aim of the enemy …; and finally the open renunciation of the Prussian soldier state.”xixSchmitt’s enemy in 1934 is not actually Versailles, Weimar, or Geneva, but rather “spiritual subjection” under a system of “liberal thought,” as had already been criticized in the Concept of the Political.

Indeed, the brochure may be read as a prise de parti on behalf of the Reichswehr and as an appeal to the construction of political unity. After 30 June 1934, Schmitt also promptly justified the state murders as “rightful state necessity” of an “immediate justice,”xx which proclaimed legitimacy against legality. Yet the text also asks anew with tragically resigned tone and tenor about the politically existent “way of being” and the ruling “human type.” After 1933, Ernst Jünger withdrew more into literature and in the following years wrote literarily significant works. Jünger’s figurative vision of 1932 he poetized in a dystopian manner in an allegoric reckoning with National Socialism in 1938 with On the Marble Cliffs.xxi Schmitt replaced the alternative of “bourgeois citizen” and “soldier” later, with Land and Sea, via the distinction between a “maritime” and “terrestrial” political existence, and identified the “son of the earth” as the legitimate political actor finally in the “figure” of the “partisan,” whom he positively elevated above the terroristic world-revolutionary.

At that time Schmitt glossed his personal copy of State Composition and Collapse of the Second Reich:xxii He expanded it with numerous references, pasted an early review from the Berliner Tageblatt of 7 June 1934 into his copy, but above all renamed the subtitle with light irony; the Victory of the Bourgeois Citizen over the Soldier now became