Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

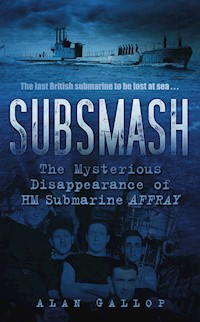

In April 1951, the disappearance of HM submarine Affray knocked news of the Korean War and Festival of Britain from the front pages.Affray had put to sea on a routine peacetime simulated war patrol in the English Channel. She radioed her last position at 2115hrs on 16 April, 30 miles south of the Isle of Wight - preparing to dive. This was the last signal ever received from the submarine. After months of searching, divers eventually discovered Affray resting upright on the sea bottom with no obvious signs of damage to her hull. Hatches were closed tight and emergency buoys were still in their casings. It was obvious that whatever had caused Affray to sink, and had ended the lives of all those on board, had occurred quickly. Sixty years later, in this compelling maritime investigation, Alan Gallop uses previously top secret documents, interviews with experts and contemporary news sources to explore how and why Affray became the last British submarine lost at sea - and possibly the greatest maritime mystery since the Marie Celeste.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 415

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

SUBSMASH

SUBSMASH

The Mysterious

Disappearance of

HM Submarine AFFRAY

ALAN GALLOP

Front Cover Illustrations: HMS Affray photographed from the starboard bow before leaving for Australia in October 1946, copyright of Wright and Logan, Royal Navy Submarine Museum (top). Members of HMS Affray’s crew in its engine room, Crown copyright (bottom).

First published in 2011

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

All rights reserved

© Alan Gallop, 2007, 2011

The right of Alan Gallop, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 7296 6

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 7295 9

Original typesetting by The History Press

This book is dedicated to the seventy-five brave officers and ratings who sailed in HMS Affray on Exercise Training Spring on Monday 16 April 1951 and never returned

CONTENTS

List of Illustrations

Foreword

Acknowledgements

1.

1951: Postwar Blues, Radio Times

2.

The Silent Service and His Majesty’s Submarine

Affray

3.

‘Dear Dad, I Think This Boat Is Just About Finished . . .’

4.

Exercise Training Spring

5.

Monday 16 April 1951: ‘Cloak and Dagger Stuff’

6.

Tuesday 17 April 1951: Subsmash

7.

Wednesday 18 April 1951: ‘Communication Has Been Established With

Affray

’

8.

Thursday 19 April 1951: The Flame Burns Low

9.

Heartfelt Sympathy, Personal Effects, Inventions and Visionary Suggestions

10.

Friday 20 April/Saturday 21 April 1951: ‘One of the Great Unfathomable Mysteries of the Present Time’

11.

Sunday 22 April/Monday 23 April 1951: ‘No Escape Was Possible by Any Means’

12.

May–June 1952: The Ugly Duckling

13.

The Broken Snort

14.

Engineers Examine the Snort Mast

15.

The First Sea Lord and Commander-in-Chief Collude

16.

The Board of Inquiry Investigates

17.

The Board Calls Witnesses

18.

‘We Do Not Concur’ and a Question of Salvage or Scrap

19.

No Mark Upon Their Common Grave

20.

‘Should I Be in His Shoes, I Should Ask For a Court Martial’

21.

A Roll-Call of Honours

22.

The

Sunday Pictorial

Exclusive: ‘We Were Not Fit to Go to Sea’

23.

‘It Happened Suddenly and None of Us Expected it,’ said the Spectre

24.

‘Who Had the Right to Send my Father to Sea in a Death Ship?’

25.

Taking Credit and the Conspiracy

26.

What Happened to the

Affray

? A Professional Perspective

27.

The Strange Case of Steward Ray Vincent

28.

‘As I Looked Down, She Looked Very Peaceful’

29.

Questions Demanding Answers

Appendix: List of Crew

Bibliography

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

1.

‘A’ class submarine snort mast and periscope, 1949.

2.

Affray

before leaving for Australia, October 1946.

3.

Affray

, Simonstown, South Africa, December 1946.

4.

Crew of

Affray

, September 1950.

5.

Jeffrey Barlow and shipmates on board

Affray

.

6.

Affray

’s Engine Room crew.

7.

Control Room, HMS

Affray

.

8.

Officers and ratings on board

Affray

, Casablanca, October 1950.

9.

HMS

Affray

and HMS

Tiptoe

, Gibraltar, 1950.

10.

HMS

Affray

, Tangier, Morocco, October 1950.

11.

The game of ‘Uckers’.

12.

Down the hatch on

Affray

.

13.

Lt Cdr John Blackburn on board HMS

Sea Scout

, spring 1950.

14.

Padre with naval ratings prepare to join the search party for the

Affray

.

15.

Search-and-rescue pilots.

16.

Ships search for

Affray

, English Channel, 17 April 1950.

17.

HMS

Amphion

.

18.

‘A’ class submarine searches for

Affray

.

19.

Annotated newspaper photograph of

Affray

.

20.

Lt John Blackburn, aged 28.

21.

Lt Derek Foster,

Affray

’s ‘Number One’.

22.

AS George Leakey.

23.

AS John Goddard.

24.

LS George Cook.

25.

Telegram sent by AS John Goddard.

26.

Marine Sgt Jack Andrews.

27.

Telegraphist Harold Gittins.

28.

HMS

Reclaim

.

29.

W. Rosse Stamp and Jock Phillips on board HMS

Reclaim

.

30.

Diver from

Reclaim

.

31.

ASDIC reading confirms location of

Affray

, 12 June 1951.

32.

‘Ugly Duckling’ casing for the underwater television camera.

33.

Underwater photograph of

Affray

’s bridge.

34.

Underwater photograph of broken snort mast.

35.

Snort mast is raised onto the deck of

Reclaim

, 1 July 1951.

36.

Snort mast undergoes tests, Admiralty’s Central Material Laboratory, Emsworth.

37.

The television camera ‘receiving station’ in the Captain’s cabin on board HMS

Reclaim

.

38.

Snort mast collar.

39.

Detail of the broken snort mast.

40–3.

Scale model of HMS

Affray

as it was found on the seabed.

44.

David Bennington’s letters reproduced in the

Sunday Pictorial

, December 1951.

45.

Submarine memorial, Royal Navy Submarine Museum.

46.

Memorial service sheets, Portsmouth, Gosport and Chatham, April and May 1951.

47.

Commemorative first-day cover, fiftieth anniversary of the loss of

Affray.

48.

Disaster Relief Fund Scheme.

49.

Grand Performance, HMS

Affray

Disaster Fund, Sunday 3 June 1951.

Diagram

Annotated profile of HMS Affray, Acheron Class Large Patrol

Submarine. (Drawn by Gary Symes)Page 8FOREWORD

Few people today have heard of HMS Affray, the Royal Navy’s ‘A’ class submarine which made its way out into the English Channel in April 1951 with seventy-five officers and ratings on board, dived and never again returned to the surface. And why should they have? Affray was the last British submarine to be lost at sea and she dived for the final time nearly sixty years ago, triggering the largest military sea-air search ever mounted in this country before, or since.

But there are sufficient numbers of people still alive who do remember the mysterious disappearance of the Affray and for some of them the memory still hurts and haunts. After all this time they still ask questions, answers to which have never been satisfactorily provided.

They ask: what really happened to Affray? What prevented her from resurfacing after she dived on the evening of 16 April 1951? Why were so many men summoned to join the submarine and then sent ashore again minutes before she sailed? What might have happened to her once she had disappeared beneath the waves? Was the submarine in a fit state to sail? Was she overcrowded? Was her crew experienced enough? Were there spies on board?

Perhaps there are no answers to these questions, but this book sets out to tell the true and in-depth story of Affray for the first time, throw new light on many issues surrounding her last ‘cruise’ and offer suggestions about what may – or may not – have happened to her. To do this, I have been fortunate to have enjoyed the co-operation of four people who lost a husband, father or brother on the submarine and others who either participated or observed the attempts to find and rescue her.

Experienced submariners – including a respected submarine commander – have also kindly provided me with their own professional perspectives, and a technical deep-sea diver describes what the vessel looked like sitting on the sea bed half a century or so after she went missing (and before diving was banned on underwater military graves).

There are many questions that could not be answered in 1951 because the technology needed had not been invented at that time. But it does exist today. When an underwater television camera was lowered into the sea for the first time from the deck of HMS Reclaim and identified a mysterious cigar-shape object on the seabed as Affray, it marked a great leap forward for salvage operations. Today’s sophisticated, highly portable X-ray and salvage equipment could be used on the wreck to obtain those answers without any need to disturb the last resting place of seventy-five men.

If the sixteenth-century Tudor warship Mary Rose could be raised from the Solent in 1982, why could the mid-twentieth-century submarine Affray also not be salvaged, too? Admittedly, Affray sits in nearly 300ft of water and a metal submarine weighs considerably more than a wooden Tudor warship. But we know that the Mary Rose was top-heavy and sank after keeling over. We do not know what caused Affray to fail – and may never find the answer, even if it were possible to carry out a detailed underwater survey. Evidence of an explosion in her battery tanks or the position of a hidden snort mast valve may – or may not – provide answers. If the Affray failed because of human error, as is suggested later in this book, it is unlikely that any hard evidence will ever be produced.

This author is not and never has been a submariner, or even a Sea Scout. The nearest he has come to a submarine is being shown over HMS Alliance at the Royal Navy Submarine Museum at Gosport (which is highly recommended) and, as a child in 1958, seeing the American submarine USS Nautilus arrive at Portland Harbour following her groundbreaking (icebreaking?) voyage under the North Pole.

I first heard about Affray from a friend who, as a boy sailor in 1951, was on guard duty at the gates of the Royal Navy Dockyard at Portsmouth when news was circulated that the submarine was overdue reporting her position while on a war patrol exercise. For some reason, the record book in which names of all visiting dockyard arrivals and departures was entered was requested by a senior officer – and never returned.

Preposterous rumours began to circulate: she had been captured at gunpoint by the Russian navy and the crew taken prisoner, there had been a mutiny on board, she had been run down by a ship while cruising at periscope depth, a pair of young female ‘passengers’ had been smuggled onto the submarine and the Navy did not want to salvage her as it would identify serious gaps in its security. And there were others, including more realistic suggestions that Affray was unfit for sea, was ‘a leaking sieve’, had not been properly tested with a deep dive before putting to sea and had some serious problems with oil appearing in one of her battery tanks. All of this, some of this or – possibly – none of this may be true.

This book avoids ‘being technical’, but where a technical term must be used, I have attempted to make sense of it and appreciate that this may rankle some submariners. During my research I learned many things about submarines: that they are often called ‘boats’, that their commanders are often referred to as ‘captains’, and operating one (and maintaining its balance and ‘trim’) is a most difficult task requiring team work of the highest order. Which is, perhaps, why HMS Affray met the unfortunate end that it did in the spring of 1951.

Subsmash first appeared in 2007 and this new and revised paperback edition has been produced to coincide with the 2013 unveiling of a new memorial to the crew of HMS Affray. In its own way, this book is the only public memorial to the Affray and her crew and I am happy for it to be considered this way.

Since publication of the first edition, I have received scores of letters, emails and telephone calls from readers across the UK and from as far as Australia and New Zealand wishing to comment on the book, share memories about their own personal connections with the Affray and her crew, pass on their own ideas about what might have happened to the submarine in 1951, or comment on what should – or should not – be done at the site where the vessel has been resting on the sea bottom for the last 60 years.

Not all of my correspondents are happy with the book. A small number told me that it should never have been written (even though they were prepared to buy a copy and read it) and that the book has stirred up sad memories from their past. One person even claimed the entire book was a pack of lies. The majority, however, were kind enough to state that they were glad Subsmash had been published because it was the first time the full – and true – story of HMS Affray had appeared in book form. Many, like others quoted in this book, lost loved ones and friends in the submarine and they told me they had learned things about the disaster that they never knew before. Others said the book is a fine way of relating how the last British submarine was lost at sea for people who had never heard about the disaster or were not around in 1951.

A small number of politicians and people from more obscure branches of the Royal Navy have also fired water pistols in my direction and challenged certain statements in this book. Since rising to their challenges and supplying them with the source of my information, I have heard nothing more from them.

This book is by no means the last word on HMS Affray. I am certain that there is more to be told in the years ahead – although it is unlikely to come from anyone mentioned in the above paragraph . . .

Alan Gallop

Ashford, Middlesex, March 2013

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author extends sincere thanks to everyone who gave me their time, shared their memories, provided images and access to personal papers, opened their archives, loaned me material and took the trouble to answer my questions.

I am particularly grateful to those who lost loved ones on HMS Affray and were prepared to revisit that time and speak to me about their memories and feelings. Sincere thanks in particular to Mary Henry (widow of Lieutenent Derek Foster), Joy Cook (widow of Leading Seaman George Cook), Robin Andrews (brother of Marine Sergeant Jack Andrews) and Georgina ‘Gina’ Gander (daughter of Able Seaman George Leakey). Thanks also to Margaret Goddard, whose husband, Leading Seaman John Goddard – who retired from the Royal Navy as a lieutenant – was one of the men discharged from the submarine before she sailed and who later did much to keep the story of Affray alive.

I also wish to thank three special people at the Royal Navy Submarine Museum at Gosport – a visit to which is highly recommended to people of all ages, especially those who want to actually go on board a submarine – for their patience and interest shown in my research for this book: Commander Jeff Tall, OBE, MNI, RN (former Director), George Malcolmson (Archivist) and Debbie Corner (Keeper of Photographs/Temporary Exhibitions Coordinator).

Many other people also took the trouble to contact me by telephone, letter and e-mail and I am grateful to: Dave Lowe, Dave March, Gordon Selby, Bernard Kervell, Brian Collis, Gordon Chatburn, Val Clements, Roma Maw, Ron Leakey, David Dyer, Alice Graham, Richard Pilgrim, Douggie Elliott, Mike Draper, Geraint Ffoulkes-Jones, W. Rosse Stamp, Peter Stephens, Captain W.H. Kett, DSC, RD, RNR, Michael Kenyon, MBE, BEM, John Rogers, Leonard Lowe, E.V. Bugden, Peter Sampson, Jeffrey Barlow, Roy ‘Tug’ Wilson and ‘MJS’.

Finally, I extend my appreciation to the unseen backroom ladies and gentlemen at The National Archives, Kew, and the British Library Newspaper Library, Colindale, whose swift efficiency ensures that researcher and authors always get what they have requested in the fastest possible time.

Chapter 1

1951: POSTWAR BLUES, RADIO TIMES

Although the war had been over for nearly six years, it was taking a long time for Britain to start feeling good about itself again. Times were hard and for many the country remained a gloomy place, lingering in an extended post-war depression not helped by wartime rationing, still in place in the spring of 1951 after twelve long, austere years.

Rationing of bread, canned and dried fruit, chocolate biscuits, treacle, syrup, jellies, soap and clothes had been lifted, but restrictions on the sale of petrol and most types of meat continued and it would be another fifteen months before rationing was completely lifted. Food quotas had been forced on the British public in January 1940, four months after the outbreak of the war when limits were placed on the sale of bacon, butter and sugar. Two months later all meat was rationed and clothing coupons introduced.

Slowly – very slowly – popular consumer products were creeping back into the shops. Bristow’s Lanolin Shampoo had returned to shelves at all good chemists in 1949, price 1s 3d or 2s for the family size. Britons no longer needed to wash their hair using carbolic soap.

Top footballer Billy Wright told newspaper readers through advertisements that ‘Quaker Oats is my food for action! (Price 9½d or 1s 7d for a bumper box)’. As there was little variety available in food, the British public took Mr Wright’s word and went into action buying the expensively priced product until the shelves were bare. HP Sauce returned to ‘improve all meals’ while Churchman’s No. 1 cigarettes had never left the tobacconist’s counter during the war and in 1951 remained ‘the 15 minute cigarette for extra pleasure and satisfaction’.

While the war in Europe was now a thing of the recent past, the country remained on a war footing. After six years of peace, it was still difficult for many people in large towns and cities to become re-accustomed to life again without air raids, sirens, separations from loved ones for months – sometimes years – or the possibility of a knock on the door from a telegram boy bringing bad news.

Abroad there was armed conflict in Korea. Armed communists had retaken the city of Seoul and United Nations and South Korean forces had crossed the 38th parallel. There was unrest in Malaya where rebels were attacking British-owned rubber plantations and demanding independence. China had occupied Tibet and British and American relations with Russia were heading towards a period soon to be known as ‘the Cold War.’ Winston Churchill had dubbed the USSR and communist countries surrounding it the ‘Iron Curtain’ and newspapers referred to the ‘Red Menace’ almost daily. Trouble was also brewing along the Suez Canal after King Farouk ordered British troops from the zone and there was talk of sending warships in to take it back.

In April 1951, the Daily Mail told readers there was likely to be a reshuffle in Prime Minister Clement Atlee’s new Labour government following the recent death of Earnest Bevin and illness of Sir Stafford Cripps, ‘compelling the PM to look for new and younger men for the cabinet.’ A cabinet reshuffle, however, was the last thing on 68-year old Atlee’s mind at the time. He was lying ill in St Mary’s Hospital, Paddington, recovering from a major operation to remove a duodenal ulcer and instructed by physicians not to sit up and work under any circumstances.

The Daily Mail also said that currency restrictions for British tourists visiting the Continent would end soon. Not that many people took foreign holidays, the majority either staying at home or spending hard-earned wages at British seaside boarding houses. You needed to be posh to stay in hotels.

Other newspapers said that millions of people in India were starving and forced to eat snails and that Randolph Turpin was ready to fight Billy Brown in a middleweight championship in Birmingham (which Turpin subsequently won by a knockout in round two). Humphrey Bogart and his wife Lauren Bacall decorated the pages of the popular press after arriving in London from the United States for a few days before going on to Africa to film The African Queen.

Radio listeners had a choice of three BBC radio stations to tune into on their Bakelite sets powered by an accumulator. Although the BBC had been transmitting programmes into British homes since the 1920s, it was during wartime years that the corporation really came into its own. For the majority of the population, a daily BBC diet of news and current affairs, music and entertainment, education and culture were a lifeline to daily information and amusement. The country loved and trusted the BBC.

On the Light Programme listeners could tune into Housewife’s Choice – ‘popular gramophone records played for the nation’s wives at home while their husbands are at work.’ The programme was followed by Joseph Seal ‘on the organ’ and the fifteen-minute long daily radio serial Mrs Dale’s Diary in which the star character (a doctor’s wife played by Ellis Powell) told the nation frequently that she was worried about her son Bob (played by Nicholas Parsons).

The Light Programme was liberally sprinkled with news bulletins and current affairs programmes surrounding other daily favourites, including Listen with Mother, another fifteen-minute show featuring children’s songs, nursery rhymes and a daily story introduced by a phrase asking children: ‘Are you sitting comfortably? Then I’ll begin . . .’ By 1951 the programme was heard by more than 1 million children (and their mothers) across the nation and other countries painted bright pink on the world map.

Listen with Mother was followed by Woman’s Hour – still a firm BBC favourite with listeners of both sexes – and later in the evening millions tuned into the latest episode of a new daily drama series, which had begun transmission four months before. It featured characters living at Brookfield Farm in a fictitious town called Ambridge and was called The Archers. People rushed home from work to eat their tea (most working people ate ‘dinner’ at lunchtime) to the sound of The Archers. Like Woman’s Hour, The Archers still has a strong radio following in the twenty-first century.

The Home Service was more a more serious station offering plays and music. Daytime programming was directed at schools and produced to be played through large Bakelite radio sets in post-war classrooms with children sitting quietly at their desks listening to BBC academics discussing geography, history, science and literature.

Programmes lightened up during the early evening hours when the noise of rush-hour cars and buses boomed out of radio sets and an announcer shouted: ‘Stop!’ And the traffic noise miraculously ceased. In more modulate tones, the announcer continued: ‘Once more we stop the mighty roar of London’s traffic and, from the great crowds, bring you some of the interesting people who have come by land, sea and air to be In Town Tonight!’

Children’s Hour (actually a fifty-five-minute long programme) comprised stories, talks, plays and drama serials and became a much loved national institution heard by millions of youngsters – mainly boys – eager to catch up with the latest adventures of schoolboy hero Jennings and boy detectives Norman and Henry Bones. In the evening, Home Service listeners tuned into Twenty Questions and The Brains Trust – programmes designed to fulfil the BBC’s charter to ‘educate, inform and entertain’ the public at large.

The Third Programme was the BBC’s heavyweight station dedicated to discerning or ‘high-brow’ listeners preferring serious classical music, concerts and plays to popular light music and 1950s’ versions of today’s soap operas. It was the corporation’s least popular channel.

Although the BBC had started broadcasting television in 1936 and Britain was first in the world to have regular scheduling of programmes, TV was still a novelty in 1951. Less than one million people owned a television set – referred by many as ‘the box in the corner’ – and spent time watching eight hours of intermittent daily programmes. BBC Television opened up at 3 p.m. with a film followed by an hour-long children’s programme starting at 5 p.m. This was followed by a two-hour long ‘interval’ before BBC Newsreel at 8 p.m. when most stories featured the ‘newscaster’ reading the news from a script like on radio with a small number of stories on film. The rest of the evening was made up of variety programmes and drama before a final news bulletin and weather forecast closed the station down at 10 p.m. sharp.

It was thanks to dramatic newspaper and radio coverage and a British cinema film that stories about submarine disasters and escapes were commonplace in the immediate post-war years. The nation was shocked in 1950 when HMS Truculent, a Royal Navy ‘T’ class submarine, was accidentally rammed by a Swedish tanker while cruising along on the surface on a cold, dark January night following sea trials in the Thames Estuary. Six men died immediately as a result of the collision and five others who had been on the bridge fell into the icy Thames water. They were rescued nearly one hour later.

Damage to Truculent’s forward section caused the submarine to sink 60ft to the bottom of the estuary, where the sixty-seven men still on board gathered in the Engine Room to prepare for emergency escape using special breathing apparatus designed to take them to the surface. All the men were able to get out of the wreck, but only ten lived to tell the tale. The night was so cold and dark and the estuary ebb tide so strong that they quickly died of drowning or exposure. The loss of Truculent and her men was the Royal Navy’s worst peacetime disaster and few thought that anything on a similar scale could ever happen again.

In the year before the Truculent disaster, British film director Roy Baker had begun shooting a feature film about a submarine disaster for the Rank Organisation entitled Morning Departure. It starred box office favourites John Mills and Richard Attenborough. After careful consideration, the Navy had agreed to cooperate with Baker, considering the film to be an accurate depiction of submarine life and an opportunity to show potential submariners that it was possible to escape from a trapped submarine. In return for lending a real submarine to the film-makers – HMS Sirdar – and allowing access to the dockyard at Portland, the Navy was allowed to suggest script changes that would more accurately reflect what was happening in the modern world of post-war submarine defence. Baker agreed and filming commenced in the summer of 1949.

In the film, Mills, playing Lieutenant-Commander Armstrong, takes his submarine – named HMS Trojan for the story – out on a short exercise. His crew are all experienced men who get along with each other, apart from Attenborough’s character – Stoker Snipe – a shy loner with marital problems at home.

At the start of the film Mills is seen telling his wife that he would be home in time for tea and later his fellow officers talk about playing cricket and meeting girlfriends when they returned to shore in the evening. Soon after diving, Mills peers through the periscope and spies an electronically operated German mine left over from the war floating on the surface. It is too late to avoid the mine and Trojan is rocked by an explosion sending it to the seabed. As both time and air begin to run out, Mills gathers the survivors together. The majority get out of the submarine using escape equipment, but the explosion has damaged some escape kits and a handful of men – including Mills, Attenborough and Able Seaman Higgins (James Hayter) – must remain behind in the stricken sub until help arrives.

Up on top a storm is raging, hampering rescue attempts by a depot ship. Down below air and food are running low. The captain of the depot ship says that further attempts to rescue Trojan would be dangerous to his men – and he orders the cables winching the sub to the surface to be cut. On hearing that rescue must be abandoned, Commander Gales of the depot ship (Bernard Lee) tells seamen on deck that the men below will die as ‘a combination of two things that might happen to anyone at sea – bad luck and bad weather’.

In the stricken submarine Mills, Attenborough and Hayter sit around the wardroom table waiting for the end to come.

MILLS: I wonder what day it is?

HAYTER: Sunday, Sir.

MILLS: Six-o-clock Sunday morning. They’ll be just about getting up for early service on the depot shop.

ATTENBOROUGH: What’ll it be like, Sir? It’s not that I’m frightened, Sir. It’s just that I’d like to know. Be the end of everything, I suppose.

MILLS: Maybe the beginning. (He reaches for a prayer book from the shelf.) Don’t you chaps think it might be rather a good idea if we joined those fellows in the depot ship? (Begins to read the Seaman’s Prayer out aloud as lights in the submarine grow dim and the camera pulls back to show the injured Trojan on the seabed and a marker buoy tossing around like a cork in the stormy water above).

The End.

While the film was being edited for release, the Truculent disaster hit the headlines. For the Royal Navy, the true story of HMS Truculent and fictitious HMS Trojan was too similar to be true and the Admiralty asked J. Arthur Rank himself to delay its release. In the end, the Royal Navy and British movie mogul arrived at a compromise: A statement would be made at the start of the film:

This film was completed before the tragic loss of HMS Truculent and earnest consideration has been given as to the desirability of presenting it so soon after this grievous disaster. The producers have decided to offer the film in the spirit which it was made, as a tribute to the officers and men of HM Submarines and the Royal Navy of which they form a part.

The Navy also insisted on a final caption at the close of the film:

The Producer gratefully acknowledges the co-operation and facilities given by the Admiralty and the officers and men of HM Submarines and the Salvage Service in the making of this film, which does not portray the latest developments in submarine escape and salvage.

Morning Departure was a 1950 British box office hit and despite its occasional stiffupper-lip approach to life in the submarine service in the face of disaster, it remains a gripping and convincing piece of cinema. The public loved the film and the press were not slow to draw parallels between what had happened in the Thames Estuary earlier that year and the story unfolding on the silver screen a few months later. Recruitment into the submarine service also doubled everywhere Morning Departure was shown.

Another major news story grabbed the headlines the following year. It was an event designed by the country’s new post-war Labour government to cheer up British people and offer a gesture of hope for the country’s future as the austerity years dragged on. It was called the Festival of Britain and took the form of a gigantic outdoor and indoor spectacle costing £11 million and celebrating the battered old country’s post-war industrial, architectural and cultural achievements. The event was to be presented on two massive London sites – a bombed out area near Waterloo Station on the south bank of the Thames, which would house the exhibition, and Battersea Pleasure Gardens, which would be home to a giant fun fair. It was held in April 1951 exactly 100 years after Prince Albert’s famous Great Exhibition had been staged in London’s Hyde Park.

The Festival of Britain was a five-month long showcase for all things British – architecture, industry, furniture, interior decoration, cars, food and the arts. The main centrepieces were the brand new Royal Festival Hall, a ‘dome of discovery’ and a strange vertical sculpture looking like a space rocket with pointed ends at the top and bottom, ‘The Skylon’. The official programme described this piece of art as ‘symbolising the spirit of new hope . . . announcing that drab, grey, funless times are conclusively over’. At night Skylon would be illuminated from within making it appear to hang in the sky with no visible means of support.

There were pavilions celebrating ‘The British land and its people, minerals of our land, power and production, sea and ships, health, sport, television, telecinema and design.’

Festival of Britain stories began appearing in newspapers months before building gangs moved onto the two sites to clear thousands of tons of blitzkrieg debris to make way for the wonders of modern Britain. Readers, listeners and a tiny handful of TV viewers were treated to daily updates about how work on the event was progressing. The public began planning day trips to London to experience the Festival of Britain for themselves, feeling they had earned the right to enjoy their country’s achievements at first hand, determined that nothing was going to knock their favourite story out of the spotlight.

But with just nineteen days to go before King George VI was to officially open the Festival and tour the site, a Royal Navy ‘A’ class submarine was easing its way from its berth at Gosport and into the Solent to take part in a peacetime ‘war game’ exercise and signalled to shore that it was about to dive. It never surfaced again and for the next four days all excitement about the Festival of Britain was forgotten while the entire nation tuned into the radio and held its breath.

HMS Affray

British ‘A’ for Acheron Class Large Patrol Submarine

This illustration shows HMS Affray as she would have looked when finally commissioned by the Royal Navy in November 1945. Affray received its snort mast in January 1950 and at the same time lost its 4in and 20mm anti-aircraft weapon to create more room for the device. The mast and its hoisting gear were fixed to the port side of the aft deck and when not in use, laid flat along the deck and ocked into position in a ‘collar’ at the side of the conning tower.

Built by: Cammell Laird & Co Ltd,

Birkenhead

Laid down: January 1944

Launched: April 1945

Commissioned: November 1945

Lost at sea during Exercise Training Spring in April 1951, with 75 officers and men on board

Reason for loss: ‘Unknown’

Pennant number: P421

Motto: ‘Strong in Battle’

Dimension: Length 281ft 9in

Beam 22ft 3in

Depth 16ft 9in

Normal crew complement: 61

(75 on board at time of loss)

Propulsion: 2 sets diesel engines

2 sets electric motors

Twin screws

Range: 10,500 miles at 11 knots surfaced

16 miles at 8 knots submerged

90 miles at 3 knots submerged

Speed: 18.5 knots surfaced

8 knots submerged

Commanding Officer at time of loss:

Lieutenant Commander John Blackburn,

DSC

(Illustration drawn by Gary Symes from information contained in original Admiralty documents)

Chapter 2

THE SILENT SERVICE AND HIS MAJESTY’S SUBMARINEAFFRAY

Submarines have been around since 1620, when a Dutchman in the service of King James I of England built a vessel, which was navigated at a depth of 12–15ft for several hours in the Thames. The first mechanically powered ‘submarine boat’ to successfully dive and resurface was christened Le Plongeur (The Diver). It was launched in Rochefort, France, in April 1863 – ten years before Jules Verne created his fictional submarine Nautilus in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea about which a character describes ‘an enormous thing, a long object, spindle-shaped, occasionally phosphorescent and infinitely larger and more rapid in its movements than a whale’.

For years sailors and maritime engineers had attempted to devise ways of producing a weapon of war that could travel underwater to attack their enemies. Propelled by compressed air stored in twenty-three large tanks to power its engine, Le Plongeur was a super-size submarine. The engine could generate up to 80hp (60kW), enough to travel distances of up to five nautical miles on the surface. Le Plongeur could not travel far or fast, but she was the first of her kind.

The submarine made its first dive the following year, but the engine was unable to cope with excessive amounts of compressed air pumped into it and Le Plongeur ran into the quay. After modifications, it dived to 30ft a few days later. The submarine never managed to dive below 33ft, but if proof was needed that a vessel could successfully submerge and travel underwater, Le Plongeur confirmed it could be done.

As late as 1900 the British Admiralty declared: ‘We are not prepared to take steps in regard to submarines because the vessels are only the weapons of the weaker nations.’ Fortunately, a group of young English naval officers decided otherwise and their exertions compelled the Admiralty to buy early-twentiethcentury submarine technology from an Irish-American designer named John Phillip Holland.

Holland’s first submarine, built by Vickers, Sons & Maxim Ltd in Barrowin-Furness in 1901, was named Holland 1 after the designer. It was while working as a teacher in New Jersey that Holland had developed an interest in the potential of developing submarines for warfare. Sponsored by an Irish revolutionary group, the Fenian Brotherhood, he built a small one-man submarine, which the US Navy bought for $150,000.

Holland accepted a commission from the Admiralty to design an eight-man craft to assist the Royal Navy’s coastal defences. It was equipped to carry and fire three 18in torpedoes and fitted with one of the first ever periscopes allowing men to watch what was happening on the surface from a safe depth below the waves. While Holland’s periscope could turn through 180 degrees, the image appeared upside down.

Powered by a 70hp electric motor and fitted with 60 battery cells located beneath the deck, Holland I could travel up to 20 miles underwater at speeds of 7 knots and dive to a depth of 100ft. She measured 58ft in length with a beam of 11ft. She weighed 100 tons and was lifted out of the water by a crane. The bridge consisted of a handrail and on it was no protection of any kind.

When surfaced she was driven at 7 knots. Fumes were so obnoxious that, as a matter of course, officers and men either fainted or became intoxicated. The wardroom was smaller than a modern-day passenger lift and conditions on board were so dangerous that the Admiralty issued a ration of white mice to be used (like canaries in coal mines) to test the atmosphere. Holland 1 was called ‘the pigboat’ and the men who sailed in her ‘pigmen’. The names were used to describe submarines and submariners for several decades afterwards.

Admiralty top brass hated the submarine, branding Holland I ‘a damned un-English’ weapon of war. Although early submarines killed more of their own men than of the enemy’s, it was no longer possible to regard them as freakish toys.

The first British-designed submarine, known as the ‘A1’, was launched in 1902. She was lost with all hands when the steamer Berwick Castle rammed her off the Nab Lightship in March 1904. But despite these early disasters, the Navy became convinced that submarines had a future and this was confirmed after enemy U-Boats came close to winning the First World War for Germany.

A publication produced for the Admiralty by the Ministry of Information in 1945 to attract volunteers to the submarine service stated:

To the layman, the submarine is a novelty, strange and little understood and the Submarine Branch of the Royal Navy is cloaked in mystery. It is the most silent branch of a silent service, for many of its activities must be kept in secret and some of its finest triumphs will remain unrecorded until after the war. The men who man the submarines must not only be specially qualified and trained but peculiarly fitted for their duties. In wartime they are not all volunteers, but it is rare for a submariner to request to go back to General Service.

British and Allied submarines played a vital part in winning the war at sea in the Battle of the Atlantic. They had helped to cut Rommel’s supply lines in the Mediterranean, supply Malta at the height of the siege, smuggle Allied generals to England and virtually destroy Japan’s merchant shipping fleet in the Pacific. They were used to carry landing parties who demolished railways and bridges, hoping that luck would enable them to return to the submarine under cover of darkness. Submarines were used to creep into the very heart of enemy harbours and blow up warships at their moorings.

By the time HMS Affray – pennant number P421 – was completed by Cammell Laird & Company Ltd of Birkenhead and received by the Royal Navy ‘without prejudice to outstanding liabilities’ at 1600 hours on 2 May 1946, submarines had proved their worth many times over. Like all ‘A’ class submarines manufactured during wartime, Affray was intended for conflicts in distant war zones such as the Far East. Following the outbreak of war in the region, submarine designers were forced to rethink how boats should be modified since existing models were unsuitable for tropical climates or large expanses of ocean.

‘A’ class vessels were specifically designed for such conditions. At 281ft 9in long, a beam measuring 22ft 3in and a height of 16ft 9in, they were more streamlined than their predecessors and could travel up to 10,500 miles at surface speeds of 18.5 knots, and 10 knots instead of the usual 8 while submerged. Affray could dive to a depth of 500ft but could go deeper if necessary without risk of her hull collapsing.

The boats also offered better conditions for their crew of officers and ratings – up to sixty-one in peacetime and sixty-six in war conditions – and although submarines were cramped and claustrophobic, ‘A’ class boats were fitted with air-conditioning and refrigeration, making life inside more comfortable. Most submariners, however, felt the extra half-crown a day they were paid for working on submarines made any discomfort worthwhile and only a few regretted ‘signing up to go down’.

Many perceived submarines as dark, cold, damp, oily, cramped and full of intricate machinery. Edward Young, who joined the submarine service as a sub-lieutenant in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve in 1940 and went on to command HMS Storm, remembered his first visit to HMS Otway at Gosport in his classic memoir, One of Our Submarines:

I was rather disappointed at the fragile and ratty appearance of this submarine. It was so different from the sleek, streamlined craft of my imagination. I was unaware that most of what I could see was a sort of outer shell which filled with water when the submarine dived. The whole of the long, narrow deck, and most of the bridge structure, were in fact pierced by innumerable holes, so as to allow this outer casing to flood when diving and drain away when surfacing. As we were led for’ard and told to climb down through a round hatch into the innards of this monster, I don’t think any of us felt very happy about it.

Once inside, Young was astonished by the size of the boat and the fact that he was able to stand up to his full height and walk about with ease. He found the hull was wider than a London tube train and was surprised by the brightness of the lighting everywhere.

‘In the messes there were wooden bunks and cupboards and curtains and pin-up girls and tables with green baize clothes. I had not expected to find so much comfort and cosiness,’ he recalled.

Affray’s accommodation space, divided between the fore-ends and the boat’s control room, was far from spacious. While messes were crowded places and wooden bunks used by the crew were short, submarine crews were quick to adapt and there were few complaints. In addition to a kit bag, the only other item submariners brought on board was their ‘ditty box’ – a plain, unpainted wooden box in which they kept personal items such as photographs, a writing pad, plus a sewing and wash kit.

The bunks concealed one of the submarine’s most vital systems – half of the boat’s 224 large lead-acid batteries, each weighing half a ton, which powered the submarine while submerged and supplied power to numerous auxiliary circuits. One hundred and twelve batteries hidden beneath the accommodation section and held in place with asbestos string, supplied the starboard switchboard and main motor while the remainder, located underneath the heads (toilets) and washroom, also supplied the main motor and port switchboard.

Officers and chief petty officers had their own bunks near their wardroom, but junior ratings wishing to sleep after a long watch sometimes had to search for a ‘hot bunk’ – a nice warm bed recently vacated by the man coming on watch. Newly joined submariners quickly learned not to be too fastidious about sharing. Not that it mattered as everyone on board hummed with the same all-pervading smell of diesel fuel which clung to clothing in the open air and on shore.

The captain was the only person on board with space to himself – a small watertight cylindrical shaped ‘room’ positioned inside the conning tower, allowing him to gain access to the bridge or the control room equally quickly. Most captains hated this arrangement, preferring to live in the wardroom with other officers where they could be in touch with everything going on – even while asleep.

Other ‘A’ class innovations included an all-welded hull, radar that could be worked from periscope depth and a night periscope. The submarines were only marginally quieter than their predecessors. Engine noise has always been a dangerous thing in submarines, allowing them to be detected by the enemy or quickly located thanks to anti-submarine sonar systems. ‘A’ class boats, however, were hardly silent beasts. Thanks to the complexity of their engines, there was no part of the boat that officers and ratings could escape for peace and quiet. Over time, submarine crews became used to the thundering mass of metal and machinery and after a while they hardly noticed the continual engine churn night and day, above water and while submerged.

Affray could carry a larger weapon load than other conventional submarines, avoiding any need to return to base from far-flung patrol areas every time its torpedoes had been fired. Its bow section was taken up by six 21in torpedo tubes (two positioned externally) and a stern compartment fitted with four 21in diameter tubes. A further four torpedo tubes – two of them external – were positioned in the stern of the boat. Each of the twenty torpedoes on board weighed around one and a half tons and carried an 805lb explosive charge. They were moved from their storage space into the firing tubes using chains, block and tackle and a great deal of sweat and muscle from the crew.

The forward torpedo stowage compartment served as the boat’s community centre. It was here that films were screened and church services held on Sundays at sea. The captain conducted services as an unpaid parson with the off-watch crew crammed into the section in between and all around torpedo tubes. The area was also one of Affray’s main escape compartments with an evacuation hatch positioned amidships. If crew needed to evacuate from their boat quickly in an emergency, they would hastily don specially designed Davis Submerged Escape Apparatus – invented by Sir Robert Davis in 1910 and better known as DSEA – and while the compartment was flooded to equalise pressure and allow the hatch to be opened, they would breathe pure air from an in-built system in the apparatus.

Affray’s control room was positioned directly beneath the conning tower and contained practically everything necessary to dive and navigate the submarine. To a newcomer, the space was a confusion of pipes, valves, electric wiring, switches, dials, wheels, levers, pressure gauges, depth gauges, junction boxes, navigational instruments and other mystery gadgets covering every inch of the area apart from the floor.

Diving and surfacing was a simple procedure. Like all submarines, Affray rose on the air in its main ballast tanks, which ran along the hull on the outside of the boat. Large free-flood holes in the bottom were always open and as soon as the main vents were hydraulically released from the control room, supporting air was released and water flooded the tanks to take her underwater. The main vents were shut when fully submerged allowing the boat to return to the surface at any time by blowing water out of the main ballast tanks using high-pressure air injection.

On-board WCs – known as ‘the heads’ – and washrooms were positioned alongside a passageway leading to Affray’s engine room. The submarine was equipped with two fresh-water distillers, but they used too much electric power to run continuously and water was always in short supply while on patrol. On longer patrols it was rationed to one gallon per man per day for all purposes, including cooking and washing up. There was no spare water for bathing and crew had to rinse dirt, oil and grease from their hands in a communal bucket before undertaking a more thorough wash in one of the washroom’s steel basins. Crew members on long patrols rarely washed, as the lyrics of a popular submariner’s song testifies:

For I don’t give a damn wherever you’ve been,

Nobody washes in a Submarine.

The Navy think we’re a crabby clan,

We haven’t had a wash since the trip began.

We’ve been at sea three weeks or more,