Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

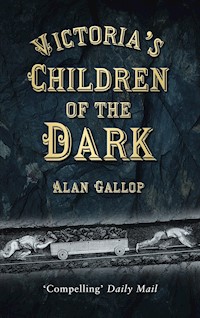

Victoria's Children of the Dark tells the story of Queen Victoria's invisible subjects - women and children who laboured beneath her 'green and pleasant land' harvesting the coal to fuel the furnaces of the industrial revolution. Following the real fortunes of seven-year-old Joey Burkinshaw and his family, Alan Gallop recreates the events surrounding the 1838 Husker Pit disaster at Silkstone, Yorkshire - a tragedy which helped lead to better working conditions for miners. Chained to carts and toiling half-naked for eighteen-hour shifts in near darkness, children as young as four were employed by mine owners. Yet it was not until the catastrophe at Silkstone when twenty-six children were drowned in a mineshaft that Victoria and her subjects realised that many Britons were existing in virtual slavery. This powerful and dramatic account exposes the real lives and working conditions of nineteenth-century miners. A gripping human story, Victoria's Children of the Dark brings history, particularly the history of childhood, vividly to life.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 446

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

This book is dedicated to the memory ofJack Wood –and the children . . .

Previously published as Children of the Dark in 2003This edition published in 2010

The History PressThe Mill, Brimscombe PortStroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QGwww.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

All rights reserved© Alan Gallop, 2003, 2010, 2011

The right of Alan Gallop, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 6927 0MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 6928 7

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Acknowledgements

Preface

Introduction: Welcome to the Silkstones

PART ONE

The Clarkes and the Silkstone Seam

Gentry, Traders and the Tommy Shop

A Collier’s Life

A Multitude of Terrifying Calamities

Moorend, Husker and the Day Hole

A Thunderstorm of the Most Terrible Character

The Exterminating Angel

PART TWO

Lord Ashley and the Royal Commission

Mr Symonds and Mr Scriven Come to Call

PART THREE

An Enormous Mischief Has Been Discovered

Out of Darkness and Into Plight

Decline and Fall

Postscript: Weeping in the Playtime of Others

Bibliography

Diagram of the Husker Pit, Silkstone, showing the day hole and Door No. 2. (Author)

Acknowledgements

Three people provided me with an abundance of material for this book. Each was wonderfully helpful and gave me more information than I could possibly have hoped for. Thanks then, to:

Jack Wood, whose own locally-produced book about the Husker Pit disaster, published in Silkstone in 1988 to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the tragedy, made me want to dig even deeper and find out more about life in his village in the nineteenth century. Jack, who passed away in August 2002, was a ‘mine’ of information and patiently answered my questions, showed me around his village and brought its history to life. Jack, you are missed by a great many people. . . .

Ian Winstanley, author and historian, whose publishing enterprise, Picks Publishing of Ashton-in-Makerfield, Wigan, has made mining history more accessible. His Coal Mining History Resource Centre website (www.cmhrc.pwp.blueyonder.co.uk) is highly recommended to anyone interested in the subject. Ian’s personal interest in this book has resulted in my obtaining rare source material and many of the illustrations reproduced on later pages. Ian’s passion for mining history is highly infectious. . . .

John Goodchild (and ‘Fern’) of the John Goodchild Collection, an independent treasure-trove of mining history, carefully catalogued and wonderfully displayed in cosy rooms below the Central Library in Wakefield. John kindly located several books for me to examine which I had previously found difficult to obtain – and produced several more rare ones he thought might also be of interest to my study. They were! John tells me that on his death, his large collection passes to the ownership of Wakefield District Council. May that day be long away. . . .

I am also indebted to: My friend Gary Symes for re-drawing an old and complicated map of the Silkstone township from 1842 which has been reproduced on the endpapers of this book; Alison Henesey at the National Coal Mining Museum for England at Caphouse Colliery, Overton near Wakefield, which provides a wonderful opportunity for people to actually travel down a real coal mine and journey into the past to experience mining history at first hand; the friendly and helpful staff, both at the Sheffield Archives (where valuable documents relating to the Clarke Family of Noblethorpe Hall, Silkstone – NRA Ref: 6593 – are made available to the public) and the British Library’s Newspaper Library at Colindale, London NW9; Robert Frost at the Yorkshire Archaeological Society, Leeds; Kath Parkin at the Barnsley Chronicle and Colin Bower of Silkstone Parish Council, who both provided me with valuable information about how the Husker pit disaster has recently – and surprisingly – forced its way back into the public conscience on two occasions, reminding us that Britain’s bad old days are never really very far away. . . .

Since Children of the Dark first appeared in 2003, I have received tremendous support from a great many people in South Yorkshire who have taken the book to their hearts, their homes, classrooms and local stages via dramatised versions. They include numerous descendants of children killed in the 1983 Husker Pit disaster who have joined together on various occasions to keep the memory of their ancestors alive. Thanks also to Jim and Dorothy Travis, Rev. Simon Moore, Margaret Bower, Doris Stubbs, Les Young, Jim Ritchie of Silkstone’s Roggins Local History Group and Stuart Berry from the National Coal Mining Museum for England near Wakefield.

Preface

This is a true story about women and young children working in Britain’s coal mines during the first half of the nineteenth century, a time when industrial labour was cheap and certain jobs could only be undertaken by those who were very young or very small. Many of the incidents and characters featured in Victoria’s Children of the Dark have fallen through cracks in British history books and much of the story related here is being told for the first time.

The Clarkes of Silkstone, the Burkinshaw brothers and their Dad and ‘Mam’, James Farrar, the Revd Henry Watkins, Jellinger Symonds, Samuel Scriven and David Swallow were all real people whose names rarely – or never – appear in more conventional books about the period popularly known as the ‘industrial revolution.’ With the exception of Lord Ashley, who gained later fame for his achievements when he inherited his father’s title of Lord Shaftesbury, these characters are unknown to the general public – but in their own way played an important part in our understanding of what it was like to work in, own or observe what went on in a Yorkshire coal mine in early Victorian times.

I came across the story of the 1838 Husker Pit disaster one Easter while visiting relatives in Yorkshire with my wife and children. My mother comes from a small village near Barnsley, my grandfather and some of my uncles had worked as colliers in the area and the sight of winding gear, spoilheaps and railway sidings for coal wagons had been familiar to me since I was born – until they were all removed following pit closures in the 1980s. Even my father, who came from ‘down south’, worked at a South Yorkshire colliery for a short time after his army discharge in 1945.

A leaflet highlighting things to see and do in and around Barnsley mentions the tragic accident, which killed 26 children when a mineshaft through which they were travelling in the small township of Silkstone flooded during a freak rain and hail storm. It showed two memorials – one marking a mass grave in which the children were laid to rest and another close to the site where the accident happened.

The former was easy to locate, rising sharply out of the ground in the local churchyard, but the second took some finding and enquiries among Silkstone’s younger locals drew blank looks. For some reason, this both annoyed and disturbed me. Annoyance because, in my opinion, they should have known where an important monument such as this was located and disturbance because I felt that the ‘children of the dark’ had been forgotten and their story lost in the mists of time.

I was therefore glad when I eventually discovered the memorial, which had been placed in a quiet spot at the edge of a wood by the people of Silkstone in 1988, 150 years after the tragedy had occurred. The children had not been forgotten at all and everyone walking their dogs, birdwatching or strolling through this beautiful place is reminded of what happened close to the spot each time they pass the memorial.

Later research directed me to coverage of the disaster in newspapers from the period and a chance meeting with Mr Jack Wood, a retired collier, lively local historian and lifelong Silkstone resident, whose own fascinating little book about the accident has sold over 1,000 copies through sales in a local pub and church.

I was also directed to archives containing documents, letters and records kept by Silkstone’s first mining family in the 1880s, the Clarkes; and a huge report produced between 1840 and 1842 by a Royal Commission appointed to examine the working conditions of women and children in the country’s mines. Until recently, the complete version of this document was hard to come by, but thanks to the energetic Lancashire writer and mining historian, Ian G. Winstanley of the Coal Mining History Resource Centre and Picks Publishing, it is now readily available. Ian has personally entered every one of the half-million – or more – words contained in the report into his computer and he will produce copies from different regions for a small charge.

A story began to emerge from this material, but, rather than write yet another industrial history, I was keen to write a human tale; the story of how people lived in those dark, distant days, what it was like for a 7-year-old child to work deep underground, what his life was like at home above ground. I wondered: could he read or write, did he get enough to eat, what mischief did he get up to? I tried to imagine what must have been going through his young mind as his first day at work approached.

The thought that the accident happened just a few days after a young girl called Victoria – no older than some of the children killed in the disaster – was crowned Queen, provided the final inspiration for this all-too human tale. The result is a story which weaves a small amount of fiction in with fact – but all of the fiction is based on fact and designed to move the story along in (what I hope) is an interesting and unusual way, relating history to people who might not normally read a history book outside school.

George and Joey Burkinshaw really worked with their Dad in the Silkstone mines. On the following pages I have put certain words into their mouths and placed them in situations which are of my own making – but practically everything that happens to them, their family and their township is based on hard evidence.

In order to make the words I have given them to say as real as possible – along with genuine testimonies given to Lord Ashley’s sub-commissioners by a variety of people – I have toned down the beautiful Yorkshire dialect speech patterns that these folk would have used in their time. Jack Wood, who, like members of my family, had a wonderful, broad Yorkshire accent, tells me that the dialect spoken in the 1880s would probably be impossible for anyone outside Yorkshire to understand today. However, I have attempted to retain a little of the rich flavour of the dialect and language of that time on these pages.*

Accounts of how colliers lived their lives at work and play, what took place at a mining village Sunday School, how a coal mine worked, what happened in Barnsley at Queen Victoria’s coronation feast, how colliers enjoyed blood sports, were evicted from their homes by minemasters, became involved with early trade unions and a hundred other details, both great and small, significant and trivial, have been drawn from a number of sources which are fully acknowledged elsewhere in this book.

* The spelling of Husker pit, for instance, is disputed: opinion tends to Husker as being closer to the original and I have used it throughout, for the later Huskar.

Introduction: Welcome to the Silkstones

A great place to be born, to grow up, to live, to grow old and to die.

Silkstone Parish Council

The township of Silkstone and its neighbouring community at Silkstone Common nestle in the foothills of the Pennines 4 miles away from the famous market town of Barnsley, once the coal mining heart of Yorkshire. The Silkstones are 177 miles north of London, 19 miles south of Leeds, 15 miles west of Doncaster and 37 miles east of Manchester.

Today, Silkstone is a quiet, pretty (some might say fashionable, estate agents will say ‘highly desirable’) and picturesque village with a population of around 2,000. Although coal was still mined from the neighbouring township of Dodworth until the late 1980s, the last ton of coal was hacked out of the ground at Silkstone in 1923, many years after its great days as a coal mining community had passed – and nearly 100 years before the rest of South Yorkshire’s mining industry collapsed during the 1980s pit closure programme, when the government of the day decided that coal-fired power plants were too expensive and natural gas and other fuels more acceptable. Coal could no longer pay its way, it was environmentally unattractive and the mines had to go. Thousands of people across South Yorkshire suddenly found themselves out of work.

In the years following pit closures, mining communities that had once been dominated by the sight of winding gear, railway shunting yards and spoilheaps – locally known in Yorkshire as ‘slagheaps’ – were transformed. It didn’t happen overnight, but as the winding gear came down and the railway lines and sleepers were torn up, pits were filled. Millions of tons of coal still lie underground and will probably never now be mined.

Without a colliery providing employment at the end of the street, thousands of Coal Board employees found it difficult to find alternative work or retrain for other occupations. And if they did find jobs, many who had only ever worked as colliers or one of the other trades at the pit top, found life on the factory floor or in a DIY superstore warehouse very different to what they, their fathers, grandfathers and great-grandfathers had been used to.

New industry eventually came to the Barnsley area, but provided nothing like the same scale of employment that British Coal plc (formerly the National Coal Board) once generated. Where collieries once dominated the skyline now stand self-assembly furniture factories, ‘high-tech’ computer manufacturing plants, foreign companies producing chemicals, pharmaceuticals and spare parts for cars.

In 2003 UK Coal plc, Europe’s largest independent coal mining company, said it was losing £26 million each year, producing around 20 million tons of coal annually in 13 mines in Central and Northern England – 5 million tons less than was produced by British mines in 1838 and nothing like the 200 million tons a young National Union of Mineworkers official (who later became president) called Arthur Scargill told the government his members could produce in 1966.

In 2010 UK Coal remains Britain’s biggest producer of coal, supplying around 6 per cent of the country’s energy needs for electricity generation. In 2009 the organisation’s deep and surface mines produced around 7 million tons of coal – 13 million tons less than in 2003. The UK Coal Group now operates just 4 deep mines and 4 suface mines (with planning permission pending for further mining projects) and employs 3,100 people in an industry that once provided jobs for 180,000 members of the NUM in Britain’s 172 coal mines at the time of the 1984-85 coal strike.

Recent casualties are UK Coal’s ‘superpits’ at Selby – Wistow, Stillingfleet and Ricall – opened by the Queen in 1966 as ‘the future face of coal’, and which ceased working in 2004, and the Prince of Wales Colliery in Pontefract, opened in 1860 and one of the country’s most consistently successful pits, extracting 1.5 million annual tons of coal for power stations. Its closure in 2002 left an estimated 8 million tons of virgin coal still to be mined from the colliery’s 5,000 metres of underground tunnels. UK Coal blamed previously undetected geological disturbances in an area where new mining operations were scheduled to take place as the main reason for the closure; problems similar to those found at Selby, where output has dwindled from 11 million tons at its peak to less than 4.5 million tons as reserves become exhausted. UK Coal claimed that if it continued mining in the area, the Selby and Pontefract collieries would sustain annual losses of around £50 million each year – ‘and that is a financial burden we cannot contemplate,’ said the company’s spokesman. And so a further 2,590 UK Coal employees have found themselves either taking special severance payments or jobs at UK Coal’s last few remaining pits.

Deep coal mining in Scotland, an industry that at its height employed more than 150,000 colliers, ended in April 2002 after 17 million gallons of water flooded the Longannet mine in Fife into receivership. Before the flooding, 500 Scottish Coal colliers extracted 30,000 weekly tons of coal. Reserves were thought to be in the region of 30 million tons of low-sulphur coal and £41 million had been invested in the mine. Scottish coal mining now continues from just 10 opencast pits.

This is very different from the coal industry’s early boom years. In 1840, 30 million tons of coal was raised, rising to 63 million tons in 1850 and 72 million 10 years later. Over 210,000 colliers worked in the country’s deep mines in 1850 and each was responsible for producing 300 tons. In 1861, Edward Hull of the Royal Geological Survey estimated that 79,843 million tons of coal still existed underneath Britain – ‘enough to last for 1,100 years’. In 1873 the organisation revised its estimates to 90,000 million tons.

Hull, however, predicted that by 1900 the country would be producing 288 million annual tons, rising to over 1 billion tons by 1940, over 4 billion by 1980 and 9 billion by 2000. ‘The total available supply will be exhausted before the lapse of the year 2034,’ wrote Hull, who then predicted: ‘America will then come to our aid in assisting the supply of coal to the world after that time.’

In a footnote, Hull added: ‘The reader will, however, concur with me in the opinion that prognostications extending to the three centuries are useless as they are likely to prove erroneous.’

With a prophetic eye to the far distant future, a learned journal of ‘instruction and leisure’ called Leisure Hour posed the question in November 1873:

Is it likely that, with all the spirit of invention on the one hand, and scientific research on the other, can do for us, we shall at some far distant day be brought to a commercial standstill for lack of coal? And will that be, as the croakers will have it, Finis Britanniae? We will not think it. We will rather think that long before our coal beds are exhausted, coal will have become competitively valueless, owing to the discovery of other and better means of producing the heat we desiderate, whether for our manufactures or for our domestic convenience and comfort. There is nothing at all absurd in the idea that science in the coming ages shall exercise a far more potent sway than man has ever yet dreamed of; and that our descendants may look upon the abandoned, not exhausted, coal mines as monuments of the ignorant energies of their forefathers, and even on the steam engine itself as a relic of a barbarous and unenlightened age.

At one time during the early years of the twenty-first century it looked as if coal mining would completely disappear from the British landscape. But in September 2008 The Observer newspaper asked readers: ‘Could King Coal reign again in Britain?’ It added: ‘When Maerdy, the last colliery in the Rhondda Valley, closed in 1989 it was hailed as the end of an era. Now British Coal seems to be back in business, with the country’s coal production set to grow for the first time since 2001 thanks to spiralling world energy prices.

Scottish Power has signed a deal with Scottish Coal to buy 2 million tons of coal a year, which the mining group says will lead to pits being opened and 100 jobs created. Powerfuel has reopened the Hatfield colliery near Doncaster, South Yorkshire, and Energy Build is reopening the Aberpergwim mine in West Glamorgan. Meanwhile, owners of Unity mine are in negotiations to sell the colliery for more than £100 million.

There is estimated to be more than 500 million tons of British coal still sitting in the earth. British coal producers meet only about a third of UK demand. The rest is imported from overseas. In 2005, 44 million tons of coal were imported.

Coal mining, more than any other industry, played a central role in the development of the British economy for nearly 300 years. Coal was of fundamental importance for industrialisation, the fuel that drove the steam engines, smelted the iron and warmed the people. It provided work for generations of men – and, for a while, women and children, too. The boom years began in the early reign of Queen Victoria, continued through the ruling years of ‘King Arthur’ Scargill and ended during the turbulent offices of Edward Heath and Margaret Thatcher.

Most of Barnsley’s slagheaps – a district across which the local newspaper the Barnsley Chronicle once proudly boasted it was ‘the voice of the coalfield’ – have been removed or landscaped and now appear as rolling green hills, country parks or scars on the landscape. Former railway shunting yards have become playing fields, golf courses and business estates. Streets of back-toback terraced houses, which surrounded every colliery, now look out of place without a pit at the end of the street. The local Miners’ Welfare – once the community tavern and meeting place of every collier – has become a themed pub or a wine bar. But how many of its inhabitants would willingly go back?

* * *

Silkstone’s stone houses, the blackened walls, flying buttresses and weird gargoyles of All Saints’ parish church, stand above a wooded glen containing oak, silver birch and a dozen other species of tree. The brownish-yellow Silkstone Beck twists and turns its way through the village towards the River Dearne, cutting a narrow, yet deep gorge through the trees and past meadows full of grazing cattle.

There is evidence that, when it rains heavily, the stream becomes a torrent, cutting a route past banks rising 5ft high in some places, between 15 and 20ft across on the bends and up to 8ft across elsewhere. The Silkstone Beck carries with it a profusion of rocks and pebbles of different shapes and sizes, all of them coated with a chocolate-brown film. When pebbles are removed from the bed of the stream and gently rubbed, the film falls away revealing normal coloured stones beneath. Silkstone people refer to the colour of water in their stream and the film covering the surface of the pebbles as ‘okker’ – or ochre; naturally produced iron oxide that finds its way into the water from deposits deep in the surrounding hills.

In summertime, Silkstone’s woodlands are cool and protecting. In the winter when it snows, they look wonderful. When it rains, their footpaths quickly turn into sticky quagmires.

The Silkstones betray little of their rich industrial past. In the early years of the nineteenth century, this was one of the most productive coal mining and agricultural communities in the region, directly and indirectly employing most of the area’s able-bodied men – and a high percentage of its women and children. In the late 1830s, it is estimated that around 30 per cent of Yorkshire’s entire mining workforce was under the age of 21, and a high proportion of that figure under 15.

Four and five-bedroom detached ‘designer’ houses with satellite dishes, double garages and smart cars parked outside now stand next to the Silkstone Beck close to original labourer’s cottages that have been modernised inside and whitewashed out. There is a golf club nearby. An artist has built a studio in one of the older houses. Village pubs have hanging baskets and some offer ‘karaoke’. There is a new pharmacy and a Co-Op selling petrol, newspapers, groceries and lottery tickets, which doubles as a post office. Silkstone residents are justly proud of their garden centre and a trendy café and bistro converted from a former industrial building.

In 2000, Silkstone was judged one of the country’s top 7 villages, winning the award for the Northern England region in a competition sponsored by the Daily Telegraph. Silkstone’s Parish Council claims that the village ‘is a great place in which to be born, to grow up, to live, to grow old and to die.’ It was not always the case.

Silkstone’s mining history becomes evident when visitors enter the large churchyard surrounding All Saints’ church, referred to in ancient documents as the ‘Minster of the Moors’. A large, dark, 4-sided stone obelisk rises 12ft into the air and an inscription on its eastern face informs readers in true Old Testament blood and thunder style (which the church’s published history now states is ‘a theology no longer accepted’) that:

THIS MONUMENTwas erected to perpetuate the re-membrance of an awful visitationof the Almighty which took placein this Parish on the 4th day of July 1838.On that eventful day the Lord sent forth His Thunder,Lightning, Hail and Rain, carrying devastation beforethem, and by a sudden irruption of Water into theCoalpits of R.C. Clarke Esq., twenty six human be-ings whose names are recorded here were suddenlySummon’d to appear before their Maker.READER REMEMBER!Every neglected call from God will appear against Theeat the Day of Judgement.Let this Solemn Warning then sink deep into thy heart &so prepare thee that the Lord when He cometh may find theeWATCHING.

Side inscriptions on the obelisk are shocking to read, revealing that ‘deposited in graves beneath lie the mortal remains’ of 15 boys and 11 girls who had once toiled in the dark, cruel, subterranean world of Robert Couldwell Clarke’s Husker Pit during the first few days of Queen Victoria’s reign. Their ages ranged from 7 to 17 years.

Passages from scripture appear around the stonework: ‘Take ye heed, watch and pray: for ye know not when the time is – Mark XIII, verse 33.’ ‘Boast not thyself of tomorrow – Proverbs XXVII, verse 1.’ ‘Therefore be ye also ready – Matthew XXIV, verse 44. There is but a step between me and death – 1 Samuel XX, verse III.’

The names and ages of each child are etched in black letters on the lower portion of the memorial, girls on the south face, boys on the north. The first two names on the boys’ side are: George Birkinshaw Aged 10 Years and Joseph Birkinshaw Aged 7 Years – Brothers.

In 1838, the stonemason incorrectly spelled their surnames or perhaps failed to check if he had got them right. Samuel ‘Horne’, for instance, was Samuel Atick. Over 160 years later, it is too late to correct them – they were the Burkinshaws – or the tragic events which took place at Silkstone one hot and stormy afternoon in July 1838, although some tried, and eventually succeeded in changing the conditions in which colliers worked during the century which followed.

This is a story of that time.

JOEY’S STORY

Monday, 25 June 1838 – about 4.00 am

Joseph Burkinshaw – known at home as ‘our Joey’ – slowly opened his eyes. Moonlight flooded through the open window, and it was bright inside the small, single-storey miner’s cottage he shared with Dad, Mam, big brother George, age 10, and the bairns – both lasses age 3 and 12 months – next to the village green in Silkstone.

Joey hated the dark. It frightened him. But he liked bright moonlit nights and you didn’t get many of them. It was nice to lay there in the sacking and straw beds which stretched across the floor from one side of the small room to the other, listening to the sounds of the night. He felt safe.

The older bairn was curled up soundly in between George and himself in a bed on one side of the room while Dad, Mam and the new bairn slept at the opposite end in the other one, everyone’s feet meeting in the middle of the tiny room.

Outside he could hear Robbie, the family’s new dog, scratching around on the end of his long rope trying to capture a rat just out of reach, an owl in a tall tree on the village green, the gentle rustle of the shallow Silkstone Beck as it flowed over mossy stones and other noises he couldn’t readily recognise. Was it one of those bats living in the tower of the Church swooping passed the window? Or was it the ghost of Sir Thomas Wentworth, escaped from his tomb in the side chapel and clanking down the road in the moonlight in the ancient armour he wore on his life-size memorial stone?

As he lay there, it dawned on Joey that darkness was something he would soon have to get used to. Now that Joseph Burkinshaw was 7 years old, a small space without any light would be part of his world – in the same way as working in Mr Robert Clarke’s Husker Pit stopped Dad and George from seeing the sun for hours and sometimes days at a time.

In just one week and a day Joey would became a trapper, a wage earner, a working man. But between now and then there was time to enjoy all sorts of adventures. There was Queen Victoria’s big Coronation feast in Barnsley tomorrow, followed by a holiday weekend in which he would slip out of his clogs and take part in running races, lake out with his pals and try to get out of going to Sunday School.

It was too soon to begin worrying about how dark it was underground. He would postpone that worry for a few more days.

His Dad coughed loudly in his sleep. More recently, George had started coughing in the night, too. Sometimes Dad would cough so violently he would wake up, get out of bed and double over, coughing, coughing. This would wake up the bairns and before you knew it, everyone was awake.

But not tonight – or was it early morning? Who could tell? From his place in the makeshift bed, Joey could see the moon still high in the sky as he turned over and drifted back to sleep to dream of sunshine, races, teacakes – and a large dark hole in a field into which men, women, boys and girls slowly descended. . . .

PART ONE

The Clarkes and the Silkstone Seam

One of the most important coal fields in the kingdom

The Mining Journal

There are no Roman ruins at Silkstone, but a community is thought to have existed on the site of the present township when Caesar’s legions sailed home in AD 410, leaving Britain to govern itself.

Four centuries later the Abbots of the Peterborough diocese granted land for the digging out of a ‘colepitte’ in the village of ‘Silchestone’, and, when their Graces’ early colliers arrived with their primitive picks and shovels, they discovered that the local populace had long beaten them to it, keeping themselves warm and making a living from coal which had outcropped on the surface in surrounding woods and countryside.

In 1306, Parliament petitioned King Edward I to prohibit the use of coal as fuel on the grounds that smoke from fires polluted the air and that coal mines were unsafe places. An Act of Parliament was passed banning its use but rescinded a few years later when a new act was passed stating, in part, that ‘There is the custom of paying the King 2d. per chaldron on all coals sold to persons not franchised by the Port of Newcastle’ – the only place in the country at the time with anything like a developed coal industry. At that time coal was known as ‘sea coal’ because ships distributed it around Britain’s coasts from Newcastle.

A man was arrested, tried, convicted and hanged for using coal in his burner. According to a 1413 Court Roll from the time of King Henry V, a group of 5 men were fined for ‘seeking out coal beneath the Lord’s waste without his consent’ in Darton, one of Silkstone’s neighbouring villages.

Top quality coal was first mined commercially in Silkstone in 1607 when an agreement was signed between two London gentlemen, Messrs Sawyer and Rodyer Royce Elmhurst, and a pair of coal miners and iron smelters from Silkstone called Robert Swift and Robert Greaves, known locally as the ‘Silkstone Smithies’. The 4 men agreed to build mills to mine both ironstone and coal found in seams outcropping in fields and woods around the village.

Swift lived in part of Silkstone known as Knabbs (or sometimes Nabs), which his family had owned since 1426. Knabbs, and its neighbouring area of Moorend, eventually became one of West Riding’s most productive mining districts and, by the mid-seventeenth century, several shallow pits in and around the immediate area produced coal in profitable quantities for local use. Robert Thwaites, a landowner who once held the manorial rights of Silkstone and owned property at Silkstone Common, operated local coal pits valued at £26 13s 4d per annum in 1649.

At this time mines were also in operation on Shiers Moor in Barnsley Manor, leased out for 60 years to Robert, Daniel and William Walker, a family of merchants and landowners with business interests in Yorkshire and London.

The first reported explosion in the district took place at the Barnsley Colliery in 1672. One man was killed, James Townende – from Silkstone. Over the next 300 years, thousands more miners would lose their lives toiling for a living beneath West Riding’s hills, farms, villages and towns.

Silkstone’s Moorend district remained productive and in 1736, Mr Cotton, a local resident, leased land there from Lord Strafford for 16 years and built the Rockley Furnace to extract ironstone and coal from the outcrops. Coal was mined from shallow bell pits, so called because on digging shafts or wells down to sizeable seams, workings were widened into the shape of a large traditional church bell. When the roof was in danger of caving in, the bell pit was abandoned and another opened further along the seam. All these primitive mines needed was some kind of human or horse-powered winding gear to raise coal to the surface from a depth of no more than 30ft.

Coal was also mined from day holes – also known as drift mines or adits – which took the form of a horizontal tunnel driven into the side of a hill or ridge, which did not require early colliers to descend into deep shafts. The tunnels were as long as ventilation or the primitive tools available would allow. By 1745, Percival Johnson of Green House, Knabbs, was selling coal from a series of day holes at 10 ‘pulls’ (coal containers) for 1s; 8 pulls equalling 1 ton.

Three generations later, his grandson, A.A. Johnson, was working coal in the same district, mining hundreds of tons of the best Silkstone coal every year. By that time some day holes led to man-made shafts connected to seams of solid coalface running like walls deep in the earth. Miners could walk down slopes to the pit bottom or be lowered in primitive wicker baskets attached to manual winding gear from where they could crawl onwards to the coalface.

At this time coal mining remained a secondary ‘cottage’ industry after agriculture, something farmers could turn to when other jobs on the land had been completed. Coal extracted was sold locally and the notion that it would become a massive industry in its own right, upon which the entire country would depend, was the last thing anyone thought about in the early 1780s.

Things, however, were about to change.

* * *

News that Silkstone was sitting on top of a potential fortune first arrived in the form of an unexpected letter in 1779 addressed to William Parker, an iron smelter with premises throughout England and Ireland – and at Field Head, Silkstone. Parker, who received the letter during a business visit to Ireland, had been purchasing coal for his foundries from opencast mines in Barnsley – and was generally dissatisfied with its performance. Excess amounts of sulphur in the coal prevented Parker’s ovens and forges from retaining the heat needed to keep furnaces white hot and productive throughout the working day. The letter, from Parker’s Silkstone manager, George Scott, told his employer in language which would not disappoint a modern-day wine connoisseur that tests had been conducted in the foundry using coal from an outcrop (referred to in the letter as ‘the Fall Head or Middle Bed’ of coal) discovered at the top of Bridge Field, owned by Mr A.E. Macaulay:

I told John Butler we must see what we could do with the Field Head coal, and he informed me that in forging with it, he observed by selecting it he had found some that he could take good heats with, and which he thought would do for the furnace, and we both determined to put up a small furnace and every night after the men were gone, make repeated trials, how far the Field Head coal that was sulphurous injured the ironstone; and we also determined to try some of the Fall Head or Middle Bed of coal and see if that were better than the Field Head coal. But before we made these trials we traced the top or Field Head bed to the outbreak and the middle bed to the same, and walked over and looked carefully where it was likely to be seen in hopes of finding it sweeter in some part than the part we had opened, in doing which one of the labourers informed us of a place where he had seen a coal, and I have the satisfaction to inform you that it proves to be a new coal, perfectly sweet and different in kind from any we have seen in this country.

It lies in two beds five feet thick asunder, the uppermost bed is 33 inches thick, the lowest 31 inches, both beds free of sulphur. We have gotten two cartloads of each bed, and I have not seen the least bit of brassy coal in getting the four cartloads. It is not strong coal for house use, but it is a tender coal that burns to a white ash and is likely to answer for the iron trade. This coal we found below Field Head House . . . next to the turnpike road, just above Mr Stanhope’s quarry. This bed of coal is not mentioned in Mr Perkins’s . . . account (of local coal mining seams) . . . I shall write again once I have received your reply to my last letter, but I could not under the circumstances of such importance rest a moment without informing you of it, for now we can do without the Barnsley coal.

Mr Perkins requests that you will send the piece of Irish butter as any amount of it can be sold in Wakefield Market.

I remain, dear sir,

Your most obedient humble servant,

George Scott.

Boreholes were sunk near the outcrop and 10yd below the surface a 4ft-high seam was discovered. A second black band of coal of around the same height was found 25yd deeper and at 86yd a third seam revealed itself. One hundred and forty-eight yards below the surface of Mr Macaulay’s field, a two and a half feet thick lower seam was uncovered, bringing the total to four seams, each on top of the other and all running more or less in the same north-west to south-easterly direction. In later years the seam was found to stretch from the outskirts of Wakefield and across South Yorkshire to Alfreton, Derbyshire. Duly, it was given a name – the Silkstone seam.

* * *

In 1787, Silkstone landowner Sir Henry Bridgeman circulated a notice around the district through his land agent Thomas Fletcher, telling anyone with the ability to read and money to spend:

For Sale, all that complete farm, situated at Noblethorpe in the parish of Silkstone and the West Riding of Yorkshire containing good enclosed lands in the possession of J. Walton as tenant at will, who shows the premises. There is a good bed of coal in most of the estate. Applications to be made to Mr Fletcher, Whitwell, near Worksop, Notts.

Noblethorpe comprised 152 acres of rolling parkland and arable fields on the edge of Silkstone. A stone farmhouse stood at the centre of the property, built at the top of a knoll and looking down on the rest of the village and towards the place where the road divided, bearing off left towards the township and to the right across the fields in the direction of Silkstone Common.

The notice passed into the hands of Jonas Clarke, an ambitious 28-yearold Barnsley-based attorney at law and businessman, who had made a fortune from wire-drawing and nail-making shops, farms and cottages in the village of Hoylandswaine, to the west of Silkstone. Clarke was looking to advance his rank and standing in the district and seeking a modest property, which he could later expand into a substantial mansion surrounded by plenty of land. Or, as Samuel Taylor Coleridge would write later: ‘To found a family, and to convert wealth to land, are twin thoughts, born of the same moment, in the mind of opulent merchants, when he thinks of reposing from his labours.’

In 1787, Jonas Clarke entertained no thoughts about reposing from his labours but he was now married to a young wife, Elizabeth, 21, and did have thoughts to ‘found a family and to convert wealth to land.’ It took Clarke five years to generate the £2,220 needed to buy the Noblethorpe estate but in 1792 he moved Elizabeth and their baby son Joseph into the farmhouse containing one good-sized room and a kitchen area downstairs, two bedrooms upstairs and space for domestic servants in the attic.

The large, workable coal beds outcropping on land surrounding the house were an attractive proposition and an opportunity to become associated with an up-and-coming industry – coal mining. Possibly, Clarke had come across a copy of a popular publication called The Complete Collier or The Whole Art of Sinking, Getting and Working Coal-Mines, &c As Is Now Used in the Northern Parts by ‘J.C.’ which had been in circulation for nearly 80 years. If Clarke had seen a copy, he would have been inspired by the following introduction:

Collieries, or the Coal Trade being of so great Advantage to the Crown and Kingdom, I have thought fit to publish this short Treatise thereof (having not met with Books of that Nature hitherto) in order to encourage Gentlemen (or such) who have Estates or Lands wherein Coal Mines are wrought or maybe won, to carry on so useful and beneficial an Imployment [sic], as this is, which I need not mention the Particulars of, both in respect of Fires, for private and publick use, as also in respect of the Revenue it brings in Yearly, or in Respect of the great Advantage it is . . . in respect of its imploying so many Thousands of the poor in these Northern parts of England, which are maintained by it, who must otherwise of Course be Beggars, or would be Starved, if Coal Mines were not carried on. . . .

The opening paragraph was enough to tempt any would-be gentleman with land sitting directly on top of coal to begin mining, and ‘J.C.’s’ little book told readers how to go about it in the form of a discourse between two imaginary characters on the best methods of harvesting coal.

Another factor influenced Clarke to buy property in Silkstone. Before moving into the farmhouse, the young entrepreneur had attended a meeting of local landowners at which plans for a 4-mile extension to the Aire and Calder Canal between Barnsley and an area east of Wakefield were presented. The proposed Barnsley Canal, would address a number of problems facing local coal and iron producers, the main one being the lack of an effective method of transporting minerals out of the narrow and steep-sided valley to market. The journey between Barnsley and Wakefield was an arduous one for a man with a packhorse or horse-drawn cart full of coal or iron. Roads were rough and turned into muddy quagmires whenever it rained for more than a day. When they dried out, deep ruts made by horse-drawn traffic made the going slow and unpleasant.

A further offshoot branch of the canal, heading from Barnsley towards the rich coal-producing communities of Silkstone and Cawthorne via a horse-drawn plateway, was agreed at a public subscription meeting in Barnsley in October 1792, presenting opportunities for the township’s iron ore and coal to be transported efficiently in barges directly from the district to the rest of the country via Wakefield, Leeds, Manchester and the Humber Basin.

An Act of Parliament incorporated the new canal in June 1793 and the project was completed 6 years later at a cost of £95,000. Shareholders included Dukes, Earls, Lords, Baronets and a Dowager Countess, who all recognised that the Barnsley area was becoming a major player in coal production and that commercial operators, including Clarke, desperately needed a better way of transporting large quantities of mineral to their buyers.

The Noblethorpe estate promised to be a most attractive investment for the Barnsley businessman and his family and one year after moving to Silkstone, Jonas Clarke, along with Earl Fitzwilliam of Wentworth Woodhouse and Walter Spencer-Stanhope of Canon Hall, Cawthorne, became shareholders in the canal extension from Barnsley through to Barnby, midway between Silkstone and Cawthorne. Sixty of the eighty-six investors, including Jonas Clarke, each put up £880 as their share in the enterprise, while Stanhope produced the rest – an impressive £1,600. It opened for operations in 1810.

The investment allowed Jonas Clarke to exploit the canal that he part-owned and fully intended to use to sell his mineral wealth to the highest buyers. With the means to transport his rich coal, Clarke would soon become one of four prominent – and rival – local ‘Coal Kings’ dominating the Barnsley mining district for the next century, exploiting outcrops, opening day holes and sinking deep shafts for coal which would be transported from Silkstone to other parts of Yorkshire and, eventually, to the rest of the country.

Although mining in this part of Britain was still an underdeveloped industry when Clarke began commercial operations on his land, value and demand for good quality coal outside of Yorkshire began to outstrip supply as soon as the canal was opened. Thanks to Jonas Clarke, and his main competitors – Earl Fitzwilliam in Elsecar, the Thorp family in Gawber and Thomas Wilson in Silkstone – it soon became a highly productive industry in its own right, eventually creating employment for hundreds of men, women, boys and girls of all ages; wretched, backbreaking, miserable, prematurely ageing and life-threatening employment, of which most of coal-hungry Britain remained for the next half century in blissful ignorance.

* * *

William Parker, the iron smelter, needed a business partner to help fund the cost of sinking boreholes across the neighbourhood in a bid to track the path of coal seams, reach agreements with farmers and proclaim their right to mine minerals from pits he intended to open. He approached Jonas Clarke, who was ready to further expand his business interests, and entered into partnership with the owner of Noblethorpe.

Together, they began exploiting the black treasure which lay beneath Silkstone’s soil, and which occasionally rose to the surface, making it relatively easy to harvest. Like other mine owners, they gave names to sections of their seam, reflecting areas under which it passed or the direction in which it headed – Whinmoor, Penistone Green, Barnsley, Halifax, New Hill, North Wood, Swallow Wood and Parkgate. Other mine owners taking coal elsewhere from the same seam named sections after people connected with early mining – hence the names Fenton’s Thin (a narrow seam), Walker’s Coal (and, presumably, nobody else’s) and Howard Coal.

Clarke and Parker discovered that all 12 seams running through the Barnsley area produced top-quality coal for use both domestically and for industry – but coal from the Silkstone seam was generally regarded as being the best fuel for manufacturing. The seam appeared in 10 separate outcrops across the village, rising to the surface at an angle of around 45 degrees before diving deeply down into the earth again. At their best, Barnsley seams varied in thickness between 5 and 10ft, although the Silkstone seam was rarely more and sometimes less than 3ft thick. In neighbouring Flockton, seams varied between 10 and 30in and from 13 to 27in in pits around Bradford and Halifax.

Clarke’s commercial interests prospered, while Parker’s iron foundry continued to obtain ore from 6 good workable Silkstone veins, which, in turn, led to the discovery of other coal beds. Silkstone coal sold for 1s 10d per ton at this time and the partners were soon operating a profitable enterprise in the township.

At the same time as workmen were digging out the canal extension towards Barnby – which would eventually become known as Barnby Basin – the Clarke-Parker partnership began sinking a new shaft on to the Silkstone seam at a small pit adjacent to where the terminal would eventually be sited. Coal from the new pit, called Basin Colliery, plus pits on the Noblethorpe estate, would eventually be shipped from this new section of canal to Goole and other parts of East Riding. Clarke also exploited local limestone deposits and opened a kiln on the canal side from which to produce a primitive form of building material called lime, similar to concrete. Landowners and farmers came from the surrounding district to purchase the product, which when mixed with sharp sand and water was used for building and repairing walls, laying down pathways and floors in outbuildings and small houses.

A larger-than-life local character called Thomas Fearn was employed by Clarke to run his lime kilns. He once went to a local ‘feast’ – or carnival – and drank too much ale at the festivities. Coming home, he became lost and curled up and went to sleep in a pig-sty next to the roadway. Silkstone’s village poet, John Ford, wrote later:

Just in his best and freshest prime,A famous hand at burning lime,A droughty man, a regular stickerTo jolly ale, that famous liquor,Great quantities of which he drinksUntil he hangs his head and winks;Like lime it takes a lot to quench him,A gallon won’t above half drench him;But when at length he’s got his fill,He falls like lime within his kiln.

* * *

In 1804, Jonas Clarke was corresponding with captains of ships and London-based merchants with a view to breaking the monopolies of North-East coalmasters by exporting his fine Silkstone coal south to the capital. Captain Richard Pearson, of Thorne (east of Barnsley, near Doncaster) furnished him with the cost of freighting coal from Yorkshire to London. The price worked out at around 45s per 27cwt, and he advised him not to go ahead on the grounds that such a small profit margin would make the venture not worthwhile.

But Clarke was a determined man with every confidence in the quality of his coal. In 1805 he made arrangements for a trial 40-ton cargo of Silkstone coal to be sold on the London market. The coal was carted to Barnby Basin from where it was loaded on to a barge bound for Goole. There it was transferred to the Ripon, bound for London, where it sold for 46s per chaldron. Commission and transportation fees plus payment to an agent co-ordinating the transaction amounted to 25s 6d per ton, leaving Clarke just 6s 10d per ton, making it hardly worth the trouble – despite remarks from a London coal merchant that ‘this was the best sample of Yorkshire (coal) that have come to the market’. It would be some years before Clarke’s Silkstone coal appeared on London’s coal markets again.

While the lime kilns became a commercial success, the canalside colliery was a failure. In 1805 an explosion occurred at the pit and 7 colliers, including women and young girls, were killed – plus John and Mark Teasdale, who had travelled to the colliery from County Durham to sink a deeper shaft. The explosion was caused by firedamp, the most destructive and awful of colliery calamities, when carburetted hydrogen (methane) gas naturally occurring in coal seams escapes into poorly ventilated shafts and tunnels. Firedamp could often be heard escaping from the mine through a low, hissing sound and when it came into contact with a lighted candle, it caused a blast, killing everyone working underground at the time.

A large funeral took place in Cawthorne, where most of the pit workers lived, and a memorial stone placed in the churchyard was inscribed:

Stop, passenger, dread Fate’s decree peruse,One stone stands here for seven interred, thou views.

Following the accident, Clarke closed the canalside pit to concentrate his efforts on his other Silkstone mines. It would not be the first time that the Clarke name would be synonymous with mining accidents resulting in loss of life or injuries to colliers.