Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

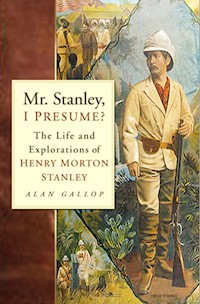

Famous for having found the great missionary and explorer Dr David Livingstone on the shores of Lake Tanganyika and immortalised as the utterer of perhaps the four most quoted words of greeting of all time - 'Dr Livingstone, I presume?' - Henry Morton Stanley was himself a man who characterised the great wave of exploring fever that gripped the nineteenth century. Yet his life and achievements are too little known and even his nationality has been mistaken. Alan Gallop draws from books, newspaper dispatches, letters by Stanley and from family archives to give a truly fascinating account of a man whose name is well known but whose life is largely unfamiliar. Often thought of, and portrayed as, an American, Stanley was born in Denbigh, Wales. Brought up in a workhouse, he fled to America in his teens and began his varied and exciting life by fighting as a soldier - on both sides - during the American Civil War and working as a journalist. It was this last job which led to the event that made him famous: he was commissioned by the New York Herald to find Dr Livingstone. His success made him a hero and during the next few years Stanley attempted to discover the source of the Nile, explored and won the Congo for Belgium and mounted a daring and disastrous - expedition to rescue the mysterious Emin Pasha from certain death at the hands of rebel forces. A rover and opportunist by nature, Stanley's journalistic outlook and forceful methods soon began to generate fierce criticism from a public who preferred their explorers to be gentlemen. Never fully accepted by the establishment - even during his more conservative later years - Stanley, as revealed by Alan Gallop, seems now more like a figure from the modern media world than from the nineteenth century.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 745

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2004

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Mr Stanley,

I PRESUME?

The Life andExplorations ofHENRY MORTONSTANLEY

Alan Gallop

This book is dedicated to the memory ofHazel Mansonwho gave encouragement to everyone she met –and who loved a good story

Title-page: Henry Morton Stanley, from Leisure Hour,25 January 1873.

First published in 2004 by Sutton Publishing

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Alan Gallop, 2004, 2013

The right of Alan Gallop to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9494 4

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

Preface

1. John Rowlands – Bastard

2. The Outcast

3. The Windermere

4. Meeting Mr Stanley

5. Life with ‘Father’

6. The Shopkeeper at Cypress Bend

7. Dixie Greys and Yankee Blues

8. Shiloh

9. A Prisoner at Camp Douglas

10. When Johnny Came Marching Home

11. Lewis Noe and Trouble in Turkey

12. Another Homecoming

13. Hancock, Hickok and the Wronged Children of the Soil

14. Mr Bennett and the New York Herald

15. Theodorus and Magdala

16. Romantic Interlude

17. The Good Doctor

18. ‘Find Livingstone!’

19. ‘Forward, March!’

20. ‘Mirambo is Coming!’

21. Life with Livingstone

22. ‘On Stanley, On!’

23. Mission Accomplished

24. ‘What Had I to Do with My Birth in Wales?’

25. ‘The Most Gigantic Hoax ever Attempted on the Credulity of Mankind’

26. New York Triumph and Disaster

27. Coomassie

28. A Living-stone

29. Lady Alice

30. Mtesa and Mirambo

31. Leopold II

32. Brazza

33. Dolly Tennant

34. Emin Pasha: Man of Mystery

35. The Rear Column

36. The Escape from Equatoria

37. Marriage and Controversy

38. The Member for North Lambeth

39. Furze Hill and Happiness

40. Loose Ends (1904–2002)

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

PREFACE

In 2002 the BBC asked viewers and listeners to name 100 men and women from history and contemporary life whom they considered to be the ‘Greatest Britons’. Over thirty thousand people voted in the poll in which Sir Winston Churchill emerged as the figure the majority wanted as the top of their personality pops. Marie Stopes came in at 100th position; others nominated included Ernest Shackleton (11), Queen Elizabeth II (24), David Beckham (33), Captain Scott (54), Cliff Richard (56), J.R.R. Tolkien (92) and Dr David Livingstone (98).

Henry Morton Stanley (1841–1904) did not rate a mention. The man whom The Times identified on his death in 1904 as ‘one of the greatest pioneer explorers and one of the most striking figures of the nineteenth century’ had been confined to history’s ‘B’ list during the last half of the twentieth century, making him an unsuitable candidate for inclusion in a table of the 100 most popular Britons. By 2002 there were insufficient numbers in Britain who were aware of Stanley and his achievements to vote him into their hall of fame.

The centenary of Stanley’s death (in 2004) is a good time to reassess the life and accomplishments of this complex, controversial and most private of men; a man whose name will forever be associated with African exploration and the subsequent fever for colonisation of the land he named ‘the dark continent’. It was his direct and indirect achievements that resulted in Africa’s subdivision among European powers and inspired the ‘Scramble for Africa’.

For most of his life, Henry Morton Stanley attempted to conceal his true identity and background. When challenged with the truth, he lied. It was only in later years when he had mellowed in appearance and manner that he agreed to confront ghosts from his past and begin drafting his memoirs. Even then, Stanley often felt a need to be economical with the truth, embellish facts or fail to mention people and events if they threatened to get in the way of his story.

Stanley died before completing his memoirs and it was left to his widow, a sensitive and capable woman, to finish the job using her husband’s unpublished journals and notes. By the time they appeared in 1909, shady figures from Stanley’s earlier life had begun to re-emerge, suggesting to Lady Stanley that they possessed evidence damaging to her late husband’s heroic reputation. Miraculously, each was in a position to part company with their evidence, written or otherwise – providing Lady Stanley was prepared to buy the material and their silence. The possibility that her husband’s reputation might be tarnished filled her with horror – and she succumbed to the blackmail. As a result, Stanley’s memoirs are heavily edited and names and identities of important characters and incidents are omitted.

Stanley set out to present an honest account of his life. The ageing former explorer stated:

There is no reason now for withholding the history of my early years, nothing to prevent my stating every fact about myself. I am now declining in vitality. My hard life in Africa, many fevers, many privations, much physical and mental suffering, bring me close to the period of infirmities. . . . Without fear of consequences, or danger to my pride and reserve, I can lay bare all circumstances which have attended me from the dawn of consciousness to this present period of indifference. . . .

Who, then, was Henry Morton Stanley, the man who admitted: ‘I was not sent into the world to be happy, nor to search for happiness. I was sent for special work’? Why did he live his life as a lie, denying his true identity and the fact that he was a poor Welsh boy, born a bastard, brought up in a workhouse, and tell the world he was an American? Who was this soldier who fought on both sides during the Civil War, this roving newspaper correspondent on the American frontier, this adventurer who walked across Africa searching for an elderly and broken Scottish missionary and, when he found him, enquired: ‘Dr Livingstone, I presume?’

From what and from whom was he running when he marched from the Indian Ocean to the Atlantic to complete Livingstone’s work, follow the mighty Congo River to the sea and claim a slice of Africa the size of Western Europe for a land-hungry European monarch? And why was he prepared to lead a daring rescue mission to relieve a mysterious and reluctant colonial official and his people from annihilation in equatorial Africa?

Stanley made a broad and deep mark on his generation. One hundred years after his death is not only a good time to re-evaluate his life and achievements but also, perhaps, to rehabilitate his reputation in a fair and objective way. To do this, it is necessary to go back to his earliest beginnings. . . .

Chapter 1

JOHN ROWLANDS – BASTARD

The ancient market town of Denbigh is one of the most historic in North Wales. Denbigh, or Denbych, derives its name from the Welsh language and means ‘a fortified place’. Fortifications take the form of a ruined thirteenth-century castle, built in 1282 for Edward I, that look down on the town and rich pastures of the Vale of Clwyd.

Visitors in the vicinity of the High Street pass the fifteenth-century timber-framed archway of the Golden Lion Inn, the sixteenth-century County Hall and narrow cobbled alleys before arriving in front of No. 7 Highgate, a medieval stone gabled building which towers above the rest of the street. A steep path leads to Burgess Tower and the entrance to King Edward’s old walled town. Tower Hill passes St Hilary’s Terraces and an unusual medieval house with battlements along the top and the castle gatehouse, from which an unpaved track leads to the site where a tiny cottage known as Castle Row once stood. It was demolished long ago, but was where one of the Victorian world’s most controversial figures is understood to have been born.

There is speculation that the baby baptised ‘John Rowlands, Bastard’, who in later life took the name of Henry Morton Stanley, may have been born in London. He wrote: ‘One of the first things I remember is to have been gravely told that I had come from London in a band-box and to have been assured that all babies came from the same place. It satisfied my curiosity for several years as to the cause of my coming; but, later, I was informed that my mother had hastened to her parents from London to be delivered of me; and that, after recovery, she had gone back to the Metropolis, leaving me in the charge of my grandfather, Moses Parry, who lived within the precincts of Denbigh Castle.’

Old Moses Parry moved into the small, whitewashed cottage known as Castle Row in the shadow of the ruined castle in 1839 when the town had a population of some four thousand. He took the property because he was a butcher and needed a house with outbuildings that could double as a slaughterhouse for cattle bound for the meat market. Years later, Dr Evan Pierce, Denbigh’s local physician and bard, told the Denbighshire Free Press he had been present at the cottage when Moses Parry’s eighteen-year-old unmarried daughter, Elizabeth – known to many as Betsy – gave birth to a son on 28 January 1841. He claimed to have recited Welsh poetry to the mother while she was in labour. Less than a year before, Betsy had left home to enter service in London where, according to her son, she had ‘thereby grievously offended her family’. By ‘straying to London, in spite of family advice, Betsy had committed a capital offence’ – in other words, she had become pregnant outside marriage; a serious and shocking thing to happen to a small-town chapel-going girl from Victorian Wales.

Denbigh’s parish register confirms that John Rowlands’s baptism took place in St Hilary’s Chapel, Denbigh on 19 February 1841 and states he was ‘illegitimate’, with the parents named as ‘John Rowlands, farmer, Llys, Llanrhaiadr and Elizabeth Parry, Castle, Denbigh’. However, a census taken in June of the same year shows no sign of Betsy and her baby living in the cottage, the new unmarried mother having fled from Denbigh in shame and disgrace with her son to return to London and work as a domestic servant. Baby John, though, was soon brought back to Wales to be cared for by his eighty-year-old grandfather and a pair of bachelor uncles in their Welsh-speaking household.

Moses, described as ‘a stout old gentleman clad in corduroy breeches, dark stockings and long Melton coat, with a clean-shaven face, rather round, and lit up by humorous grey eyes’, occupied the upper floor of the cottage with baby John, while Young Moses and Uncle Thomas inhabited the lower rooms. Young Moses later married ‘a flaxen-haired, fair girl of a decided temper’ called Kitty and ‘after that event . . . [they] seldom descended to the lower apartments’.

Stanley never knew his father: ‘I was in my “teens” before I learned that he had died within a few weeks after my birth.’ This is the first of many untruths, inaccuracies or misleading statements the elderly Stanley made while relating the story of his colourful early life. ‘John Rowlands, farmer’, in fact, passed away thirteen years after his son’s birth. He is known to have been a drunkard and his burial entry in the Llanrhaiadr Parish Register states that he died in May 1854 of ‘delirium tremens’, a severe psychotic condition that affects alcoholics. Rowlands contributed nothing to his son’s welfare, upkeep or well-being. He showed no interest in the boy after his birth or, it would appear, in the young girl he is said to have impregnated in 1840.

A Denbigh legend, persistent since the mid-nineteenth century, suggests that James Vaughan Hall, a local solicitor, alderman and leading citizen may have been Stanley’s real father. In 1840 Betsy Parry worked in a bakery shop next to offices Vaughan Hall shared with another solicitor in Vale Street. Vaughan Hall, who had a second home in London where Pigott’s Directory states he was ‘a Master Extraordinary in Chancery and Commissioner in all the Courts at Westminster’, is said to have seduced the young baker’s girl and when she discovered she was pregnant with his child, in order to safeguard his marriage and position in Denbigh society, bribed John Rowlands into claiming he was the father.

Many affluent Victorian middle-class employers considered servants and working girls ‘fair game’, and Vaughan Hall’s frequent excursions to London to undertake official duties in Chancery while his wife remained in Denbigh, would have provided plenty of opportunity to seduce young women in his employ. Dr William Acton, who practised in London from 1840, noted in his book Prostitution: ‘Seduction of girls from the lower orders is a sport and a habit with vast numbers of men, married and single, placed above the ranks of labour.’

Another local story suggests Betsy Parry was a girl with loose morals, an amateur prostitute who was having simultaneous relationships with both John Rowlands and James Vaughan Hall – and when her pregnancy was discovered, had no idea which man was the true father of her unborn child. Betsy went on to have more illegitimate children by two other men, one of whom she subsequently married. Her second illegitimate child, a daughter called Emma born in 1842, was to a man called ‘John Evans, Liverpool, farmer, late of Ty’n’ y Pwll, Llanrhaiadr’. One may well speculate that if Betsy had been employed as a servant at Vaughan Hall’s London home, she could easily have been ‘fair game’ for the solicitor, resulting in the birth of one – possibly even two – children out of wedlock, with John Evans similarly bribed into falsely admitting he was father of the second offspring.

So, was young John Rowlands, born to Elizabeth ‘Betsy’ Parry in 1841, really John Vaughan Hall? It is unlikely the young man ever discovered the identity of his real father. The only thing certain was that the stigma of being born out of wedlock in a provincial Victorian Welsh market town was sufficient to leave a deep scar on the psyche of the strongest men – and something that pursued the man, later known to the world as Henry Morton Stanley, for the rest of his life.

Stanley was aged four when he accidentally dropped a glass jug he was carrying to collect water from the castle well. It smashed to pieces and on hearing the crash grandfather Moses came to the door and ‘lifted his forefinger menacingly and said, “Very well, Shonin, my lad, when I return, thou shalt have a sound whipping. You naughty boy!”’ With that, grandfather Moses left the cottage to attend to some business in a nearby field where he promptly fell down dead. A jury at the inquest returned the verdict he had died through ‘the visitation of God’, which was their way of explaining any sudden fatality of this kind.

The death of Moses Parry was just the excuse Young Moses, Uncle Thomas and Aunt Kitty needed to rid Castle Row of their tiny nephew. The boy was transferred to the care of an elderly Welsh-speaking couple, Richard and Jenny Price, caretakers of the local bowling green 400 yards from Castle Row. Their cottage was appropriately named Bowling Green House and the two uncles agreed to pay the couple half a crown a week for his board and lodgings.

At infant school in the crypt at St Hilary’s Church, the lad was never going to be tallest in the class, but the Prices’ dismay at his increasing appetite resulted in the elderly couple asking the uncles for extra money for his upkeep. By now they were both married and were expected to bring home decent wages to keep their spouses happy. The wives told the Prices that times were hard, they could no longer afford to pay for the up-keep of their nephew and there was no room for him at Castle Row – ‘so the old couple resolved to send me to the workhouse’.

In 1847, the Prices’ son, Dick, was given the task of taking the boy to the St Asaph’s Poor Law Union Workhouse under the pretence they were going to visit an aunt called Mary in Ffynnon Beuno 6 miles away. Stanley recalls:

The way seemed interminable and tedious, but he did his best to relieve my feelings with false cajoling and treacherous endearments. At last Dick set me down from his shoulders before an immense stone building, and, passing through tall iron gates, he pulled at a bell, which I could hear clanging noisily in the distant interior. A sombre-faced stranger appeared at the door, who, despite my remonstrances, seized me by the hand, and drew me within, while Dick tried to soothe my fears with glib promises that he was only going to bring Aunt Mary to me. The door closed on him, and, with the echoing sound, I experienced for the first time the awful feeling of utter desolateness.

St Asaph’s Workhouse was an institution to which the aged poor and superfluous Welsh-speaking children of local parishes were taken ‘to relieve the respectabilities of the obnoxious sight of extreme poverty, because civilisation knows no better method of disposing of the infirm and helpless than by imprisoning them within its walls’.

St Asaph’s was created in 1837 and its operation ruled over by an elected board of 24 guardians representing 16 local parishes. The large red-brick workhouse was built between 1839 and 1840 at a cost of £5,499 16s 8d on a site 6 miles east of Denbigh and south of the village of St Asaph. It was intended to accommodate 200 inmates and for most of its early life its grey and dismal wings and dormitories were full to bursting. Its design followed the popular ‘cruciform’ layout with four separate accommodation wings, known as ‘wards’, for different types of inmate – male or female, young or old, infirm or able-bodied – radiating from an octagonal central house containing the institution’s offices and the residence of the schoolmaster, James Francis – ‘soured by misfortune, brutal of temper and callous of heart’.

Everyone entering the workhouse was subjected to a rigorous means test to assess ‘suitability’ for admission. Only ‘deserving’ cases were allowed in: the unemployed, the ill, the aged, orphaned families and individuals with nowhere else to go. Once inside, inmates were forced to undergo prison-like discipline, living in cheerless surroundings, eating plain and monotonous meals in silence. Visitors were not encouraged and occasional gifts left at the door by benefactors rarely found their way to inmates, being considered an unnecessary relaxation of workhouse regulations.

Inside the institution, young John Rowlands quickly found that the aged were subject to stern rules and assigned useless tasks, while children were chastised and disciplined in a manner that ignored the rules both of justice and charity. To the old, St Asaph’s was a house of slow death; to the young, it was a house of torture. Paupers were the failures of Victorian society and their fate was to eke out the rest of their miserable existence within workhouse walls, picking loose fibres out of discarded ropes to be re-threaded into new coils.

Male and female inmates were lodged in separate sections of the workhouse, enclosed by high walls with every door locked, barred and guarded to preserve the questionable ‘morality’, a practice which went on in hundreds of similar institutions across the British Isles. Each inmate was required to wear regulation clothing made from cheap fabric: men were clad in grey blanket trousers, matching jacket and collarless cotton shirt with hair shaved close to the skull, the women in striped cotton dresses, their short hair making one inmate indistinguishable from another.

At 6 a.m. sharp, inmates were roused from their sleep and by 8 p.m. they were locked in their wards. Bread, thin soup, rice and potatoes were the daily diet. On Saturdays inmates had to undergo a severe scrubbing in a tin bath and on Sundays were forced to sit through long services on hard bench pews in the chapel. The routine was designed to afflict minds and break spirits, which it successfully achieved within a short space of time.

Like John Rowlands, the majority of workhouse children spoke only Welsh and lessons in the St Asaph’s classroom were conducted entirely in that language, although religious instruction was given in English.

Meticulous records of daily life at the St Asaph’s workhouse are stored at Hawarden Records Office. They give the names of every arrival and departure, details of those who absconded – and were dragged back – of visitors and comments about activities and incidents. In 1847, weeks after John Rowlands entered St Asaph’s, a committee was formed to investigate conditions at the workhouse and report its findings to the Board of Education. It noted that young girls were brought into close association with prostitutes and ‘learned the tricks of the trade’. Inspectors observed that ‘the men took part in every possible vice’, children slept two in a bed, an older child with a younger, resulting in their starting ‘to practice and understand things they should not’. The inspectors’ findings were subsequently published as a report by the Commission of Education in Wales, 1849, but comments about sexual depravity at St Asaph’s were diluted.

Four decades after leaving St Asaph’s, Stanley’s resentment at how Dick Price had tricked him into the workhouse was still evident. ‘Dick’s guile was well meant, no doubt, but I then learned for the first time that one’s professed friend can smile while preparing to deal a mortal blow, and a man can mask evil with a show of goodness. It would have been far better for me if Dick, being stronger than I, had employed compulsion, instead of shattering my confidence and planting the first seeds of distrust in a child’s heart,’ he recollected.

Not that young John Rowlands received any special treatment from James Francis, a former collier from Mold who had lost his entire left hand in an industrial accident years before and wound up as workhouse schoolmaster. He won the job over other applicants because he could communicate in broken English. According to Stanley, Francis was a violent and brutal man. ‘The ready back-slap in the face, the stunning clout over the ear, the strong blow with the open palm on alternate cheeks, which knocked our senses into confusion, were so frequent it is a marvel we ever recovered them again,’ he recalled. ‘Whatever might be the nature of the offence, or merely because his irritable mood required vent, our poor heads were cuffed, and slapped, and pounded, until we lay speechless and streaming with blood.’

For young Rowlands and fellow youthful inmates, Francis’s cruel blows with his bony right fist were preferable to deliberate punishment with the birch, ruler, or cane ‘which, with cool malice, he inflicted’ from a selection of instruments never far from his reach. Even the smallest classroom error caused Francis to reach for ruler or cane. Woe betide any child who managed wrongly to answer several questions in a row for ‘then a vindictive scourging of the offender followed, until he was exhausted, or our lacerated bodies could bear no more’.

The boy’s own first flogging from Francis happened on a Sunday evening during the early part of 1849. The eight-year-old was sitting with other children listening to Francis reading aloud from Genesis 41, a passage referring to Joseph, sold as a slave by his brothers and elevated to high rank by the pharaoh. Francis suddenly looked up from his Bible and demanded to know from John Rowlands who in the story had interpreted the pharaoh’s dreams. The boy replied: ‘Jophes, sir.’

The master thundered: ‘Who?’

‘Jophes, sir.’

‘Joseph, you mean?’

‘Yes sir, Jophes.’

Francis reached for his birch and ordered the boy to ‘unbreech’, unaware he had merely mispronounced Joseph’s name. Stanley tells us that the master ‘rudely tore down my nether garments and administered a forceful shower of blows, with such thrilling effect that I was bruised and bloodied all over, and could not stand for a time. During the hour that followed I was much perplexed at the difference between “Jophes” and “Joseph” as at the particular character of the agonising pains I suffered. For some weeks I was under the impression that the scourging was less due to my error than to some mysterious connection it might have had with Genesis.’

Floggings were part of daily life at many workhouses, where it was not uncommon to see little wretches flung onto the flagstones in writhing heaps or standing with frightened eyes and humped backs to receive the shock of a sadistic schoolmaster’s birch. Nothing exists to suggest that life at St Asaph’s was any different.

The boy received another thrashing in 1851 when cholera was raging through North Wales and inmates were forbidden to eat fruit of any kind. John Rowlands and another boy were sent to town on an errand and on the journey back gorged on blackberries picked from a hedgerow. On their return to St Asaph’s, tell-tale fruit stains on fingers and around mouths gave the game away and it was only a matter of time before Francis appeared in the dormitory doorway. He reminded everyone that he had expressly forbidden them to eat fruit and ‘then, giving a swishing blow in the air with his birch, he advanced to my bed and with one hand plucked me out of bed, and forthwith administered a punishment so dreadful that blackberries suggested birching ever afterwards’.

Information on how the St Asaph’s Workhouse was organised was meticulously recorded in the North Wales Gazette, which sent a reporter along every fortnight to cover meetings of the parish guardians. On 17 July 1850, the paper reported:

Mr. J.J. Foulks thought there was a great deal of difference between the charge for the keep of the officers of the house and its inmates. The charge per head being 6s 6d and only 2s allowed for rations to the paupers. A discussion took place upon the subject but nothing particular was done towards remedying the complaint.

Details of the regime under which St Asaph’s inmates suffered eventually reached the ears of the Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald, which in later years accused James Francis of ‘coming in drunk’ and ‘taking indecent liberties’ with female staff. Strangely, this was never mentioned in Stanley’s account of his workhouse years.

Inmates were expected to fulfil difficult tasks, including sweeping the playground with brooms more suited to giants than little children, washing stone floors, hoeing the frozen ground wearing thin clothing that provided scant protection from the raw winter wind, and being forced to commit whole pages of text to memory during the space of an evening. ‘In these and scores of other ways, our treatment was ferocious and stupid,’ Stanley recalled.

‘Ferocious and stupid’, perhaps, but the overall standard of education at St Asaph’s was often better than at other schools in the Denbigh area. Stanley says that by the time he had reached age ten, several boys had demonstrated qualities superior to others students at the best public schools. Naturally, he himself was one of them. One boy, named ‘Toomis’, was a born mathematician, while ‘another was famous for retentiveness of memory’. George Williams was ‘unusually distinguished’ for quick comprehension, while ‘Billy’, with his big head and lofty brow, astonished Her Majesty’s Inspector, who prophesied great things of him in future.

Notable workhouse visitors included a bishop, local parsons, the Chairman of the Board of Guardians and school inspectors who found most workhouse children to be above average in intelligence, their education based on religion and industry while in other schools the curriculum was more secular and less physical. Workhouse guardians attempted to turn St Asaph’s boys into farmers, tradesmen and mechanics ‘and instead of the gymnasium, our muscles were practised in spade industry, gardening, tailoring and joiner’s work’. Several St Asaph’s inmates went on to become businessmen, ministers of the Church, lawyers – and African explorers. Of himself at that time, Stanley writes: ‘I, though not particularly brilliant in any special thing that I can remember, held my own as head of the school.’

The workhouse was also responsible for Stanley’s zealous passion for order and cleanliness that remained with him throughout his life. When it was his turn to clean dormitories and make beds, he was seized with an all-consuming desire to arrange bed covers without a single crease, produce folds with mathematical precision, dust and polish cupboards and window sills until they were spotless and make dormitory flagstones shine like mirrors. Years later, the former workhouse boy would ensure his camps in the African interior were arranged in similar fashion and each occupant of a canvas tent brought its contents out to be aired before taking them back inside to be arranged with the same precision as those within his own tent.

Whether James Francis was as brutal as Stanley would claim in later life is open to conjecture. Indeed, it appears that young Rowlands was something of a teacher’s favourite, often left in charge of the class when Francis left the room or was called away. The schoolmaster is remembered as ‘having a high opinion of young Rowlands and used to put him in charge of the boys in his absence’, according to a Denbigh Free Press article published after Stanley’s death.

The boy was quite equal to the task of maintaining discipline. He would allow no one to question his authority. Rather than suffer anyone to take liberties with him, he would give the boys a good thrashing all round, and this he used to do so effectually that no one was found bold enough to dispute his authority. The boy was particularly fond of geography and arithmetic, and seemed never so happy as when, pointer in hand, he was allowed to ramble over the map at will. He seemed to the boys to have the latitude and longitude of each place at his fingers’ ends. He was also a good penman, and on this account was often selected by the porter to enter the names of visitors in a book kept for that purpose and at times he was even invited into the clerk’s office to help with the accounts.

The owner of a cake shop near the workhouse told the Denbigh Free Press that he remembered John Rowlands. ‘Whenever [Francis] received a few shillings from friends to spend for the benefit of the workhouse boys, he used to visit her shop and generally brought Rowlands with him to carry the cakes home. He brought the boy with him . . . because he was very fond of the boy and thought much of him. Again and again he used these words with reference to Rowlands: “You mark me, this boy will be a great man some day.”’

One of the most popular boys in the institution was Willie Roberts – ‘a boy of about my own age. Some of us believed he belonged to a very superior class to our own. His coal-black hair curled in profusion over a delicately moulded face of milky whiteness. His eyes were soft and limpid, and he walked with a carriage which tempted imitation.’ While confined to the infirmary ‘with some childish malady where I lay for weeks’, rumours circulated that Willie had died and his body been taken to the ‘dead-house’, a room set aside and sometimes used as a morgue.

On returning to St Asaph’s, some boys suggested it was possible to view Willie’s dead body,

and prompted by a fearful curiosity to know what death was like, we availed ourselves of a favourable opportunity, and entered the house with quaking hearts. The body lay on a black bier, and, covered with a sheet, appeared uncommonly long for a boy. One of the boldest drew the cloth aside, and at the sight of the waxen face with its awful fixity we all started back, gazing at it as if spellbound. There was something grand in its superb disregard of the chill and gloom of the building, and in the holy calm of its features. It was the face of our dear Willie, with whom we had played, and yet not the same, for an inexplicable aloofness had come over it. . . .

The sheet was drawn back further, to reveal scores of dark weals and bruises covering young Willie’s body. The boys quickly replaced the sheet and withdrew from the dead house, convinced that Francis’s brutality was the cause of their friend’s death.

This author could find no trace of a boy called William – or Willie – Roberts having been admitted to or having died at St Asaph’s workhouse between 1850 and 1854. Deaths were entered into workhouse records in a neat hand leaving no room for error. Either John Rowlands dreamt up the story while in a state of delirium in the infirmary, or an elderly man called Henry Morton Stanley invented the tale as yet another piece of fiction to add spice to the story of his early years.

In later life Stanley was adamant that ‘there are two things for which I feel grateful to this strange institution of St. Asaph. My fellowman had denied to me the charms of affection, and the bliss of a home, but through his charity I had learned to know God by faith, as the Father of the fatherless – and I had been taught to read. It is impossible that in a Christian land like Wales I could have avoided contracting some knowledge of the Creator, but the knowledge gained by hearing, is very different from that which comes from feeling. Nor is it likely that I would have remained altogether ignorant of letters. Being as I was, however, the circumstances of my environment necessarily focussed my attention on religion, and my utterly friendless state drove me to seek the comfort guaranteed by it.’

John Rowlands was aged nine (although he wrote in his memoirs ‘I must have been 12’) when he came to realise a mother was indispensable to every child and that his own mother, Elizabeth ‘Betsy’ Parry, had been admitted to St Asaph’s workhouse ‘with her bastards’, Robert, aged two and Elizabeth, aged one year old, on 3 December 1850. The boy’s first feeling ‘was one of exultation that I also had a mother and a half-brother and a half-sister, and the next one was of curiosity to know what they were like and whether their appearance portended a change in my condition’.

It was Francis who pointed out Betsy to her son when inmates were assembled in a hall. He indicated ‘a tall woman with an oval face, and a great coil of dark hair behind her head’ and asked the boy if he recognised her. He told the master he did not.

‘What, do you not know your own mother?’ asked Francis.

Apart from passing a few days with her following his birth eleven years before, he had spent the rest of his life with relatives, strangers and, for the last five joyless years, at St Asaph’s. The boy directed a shy glance at the woman and thought she, too, was regarding him with a look of ‘cool, critical scrutiny’. He had expected to feel tenderness for her but her expression was so chilling ‘that the valves of my heart closed as with a snap’. The phrase ‘honour thy father and mother’ had been repeated to him scores of times, ‘but this loveless parent required no honour from me. After a few weeks’ residence my mother departed, taking her little boy with her, but the girl was left in the institution; and, such is the system prevailing, though we met in the same hall for months, she remained as a stranger to me.’

Betsy and her other two children were discharged from St Asaph’s on 2 April 1851, but two months later her eight-year-old daughter ‘Emma Jones, a deserted bastard’ was admitted to the workhouse. Betsy had farmed her second child out to a family called Morris who lived near Castle Row. The child is described in workhouse day relief books as ‘Emma Jones, alias Parry’ and later as ‘Emma Parry’. She remained at St Asaph’s until discharged, aged fourteen, in March 1857 when it is recorded that ‘she has gone upon trial to Mr. C. Owens, joiner, Rhyl’, and it is to this half-sister that Stanley refers as ‘the stranger’. Emma died in Denbigh, aged thirty-seven, in 1880. She lived long enough to boast about her half-brother’s African exploits and, after marrying local man Llewellyn Hughes, named her second child Emma Stanley Hughes and her third Henry M.S. Hughes in honour of her ‘American’ relative.

Long hours locked in a dormitory gave John Rowlands time to read, write and draw. A local chaplain visiting the workhouse left some pictures of cathedrals and, with nothing better to do, the boy copied them and discovered he possessed a natural talent for drawing. Someone else gave him pencils and a drawing book and word soon travelled around the workhouse that young Rowlands was the institution’s ‘resident artist’. Word of his talent reached the Right Reverend Thomas Vowler Short, Lord Bishop of St Asaph’s, who, on his next workhouse visit, rewarded the boy with a Bible in recognition of his diligent application to his studies; it was one of the first things the boy actually owned outright and could claim to be his and nobody else’s.

Unlike his frame, the boy’s talents in choral singing and public speaking began to grow. By his early teens, John Rowlands was still small in stature. Fellow inmates who had entered St Asaph’s at the same time, began leaving the institution to enter service or take jobs with Denbigh employers. But no one came to claim young Rowlands and he remained at St Asaph’s, becoming its oldest junior inhabitant.

He was thirteen years old when he learned an important lesson in dealing with other people; it was one he would always carry with him. One day Francis was absent from St Asaph’s and John Rowlands was deputised to supervise a class. The sight of a slightly built boy standing in front of thirty other children made him a target for unruly pupils and those who preferred a day’s play while their schoolmaster was away. A youth who had earlier bullied Rowlands in the playground decided to make the tiny temporary teacher’s life more difficult and persisted in disrupting the class. Following Francis’s usual practice, Rowlands ordered the boy to stand in the punishment corner. The boy refused and demanded a classroom fight. For once, Rowlands managed to come out on top and with the aid of a woollen scarf tied up the disruptive boy and ‘conducted him to the opprobrious corner, where he was left to meditate, with two others similarly guilty. From the hour when the heroic whelp was subdued, my authority was undisputed. Often since have I learned how necessary is the application of force for the establishment of order. There comes a time when pleading is of no avail.’

The parting of the ways for John Rowlands and St Asaph’s workhouse came suddenly and unexpectedly, but the precise circumstances are open to debate. It was an event which he later described as having ‘lasting influence on my life’ and had it not occurred, he might eventually have been apprenticed ‘to some trade or other, and would have mildewed in Wales’. The account is almost certainly fictitious.

Stanley states that by the age of fifteen he had unconsciously contracted ‘ideas about dignity’ and that ‘the promise of manhood was manifest in the first buds of pride, courage, and resolution’. Francis, however, had failed to notice any change in the boy. In May 1856 a new softwood table was delivered to the workhouse and its surface dented ‘by some heedless urchin’ who had climbed on it. When Francis discovered the damage he erupted into a rage and reached for his birch, intent on thrashing anyone in his sights.

The schoolmaster burst into the classroom demanding to know who was responsible for damaging the table. The inmates were ignorant that a new table had been delivered, let alone that it had been damaged. ‘Very well then,’ screamed Francis, ‘the entire class will be flogged – unbutton!’

Francis began thrashing the children closest to where he was standing, gradually beating his way through the class. Normally young Rowlands would have been convulsed in fear as his turn approached, ‘but instead of the old timidity and other symptoms of terror, I felt myself hardening for resistance. He stood before me vindictively glaring, his spectacles intensifying the gleam in his eyes.’ Glowering at John Rowlands, he spat out: ‘How is this? Not ready yet? Strip, sir, this minute; I mean to stop this abominable and barefaced lying.’

Calmly, the boy replied: ‘I did not lie, sir. I know nothing of it.’

‘Silence, sir. Down with your clothes.’

‘Never again!’ shouted the lad, surprised at his own audacity. Before anything else had time to sink in, Francis’s one good hand grabbed the boy’s collar, swung him into the air and down onto the bench where he was kicked in the stomach. Then the savage master lifted the boy and flung him onto some desks.

Stanley takes up the story of what happened next:

Recovering my breath, finally, from the pounding in the stomach, I aimed a vigorous kick at the cruel master as he stooped to me, and, by chance, the booted foot smashed his glasses, and almost blinded him with their splinters. Starting backwards with excruciating pain, he contrived to stumble over a bench, and the back of his head struck the stone floor; but, as he was in the act of falling, I had bounded to my feet, and possessed myself of his blackthorn. Armed with this, I rushed at the prostrate form, and struck him at random over his body, until I was called to a sense of what I was doing by the stirless way he received the thrashing.

The boy was puzzled about what to do next. His rage had disappeared and he began to think he should have taken his punishment. But why? He had done nothing. Someone suggested the schoolmaster be dragged from the classroom and some boys pulled the lifeless figure towards his private rooms. Those remaining began to cry for fear of what might happen next.

John Rowlands had to find a way out of this mess. His friend Moses ‘Mose’ Roberts asked what they should do. It occurred to them that Francis might be dead and the wrath of the law would come down on them all – especially on John Rowlands. Mose said they must run away, but not before sending someone to check whether Francis was still breathing. A boy peeped into his rooms and found the schoolmaster had staggered to his feet and was washing his bloody face at the sink.

Together John and Mose slipped over the workhouse garden wall and took off across the fields. They ran with a belief that things could only get better. In fact they were soon to get much worse.

The story of how John Rowlands and Moses Roberts absconded from St Asaph’s workhouse is uncannily similar to a parallel incident in Charles Dickens’ Nicholas Nickleby. Substitute St Asaph’s workhouse for Dotheboys Hall, James Francis for Wackford Squeers, John and Moses for Nicholas and Smike and readers are presented with a retelling of the classic story relocated to North Wales. The real circumstances surrounding John Rowlands’s and Moses Roberts’s departure from the workhouse were in reality very different.

The entry concerning John Rowlands’s discharge recorded in parish workhouse records makes no mention of any conflict between the boy and his schoolmaster. Inmates absconding from the institution were always named and reasons for their leaving explained. Moses Roberts is shown to have ‘run away’ from St Asaph’s on 24 July 1855 – almost a year before John Rowlands left. Records show Moses’s conduct was ‘good’, but no effort seems to have been made to bring him back to the workhouse. At age fifteen he would soon have left to take employment.

No other boys were discharged on the same day that John Rowlands was permitted to leave – not ‘run away’ from – St Asaph’s on 13 May 1856, ten years after admission. The entry reads: ‘Gone to his uncle at the National School, Holywell’. Apart from mistakenly stating ‘uncle’ – actually his ‘cousin’ – the entry is correct. Denbigh legend has it that as John Rowlands left the workhouse, Francis stood at the doorway and handed him a shiny new sixpence as a farewell gift.

It is possible there was conflict between the schoolmaster and Moses Roberts, forcing the boy to run away, although nothing confirming this appears in workhouse records. The episode in which a student thrashes a schoolmaster, therefore, appears to be a fantasy invented by Henry Morton Stanley to give his workhouse reminiscences a thrilling climax.

Whatever the true circumstances, in 1863 Francis was committed to the Denbigh Lunatic Asylum, by which time John Rowlands was working as a lawyer’s clerk in Brooklyn, New York – a world away from Wales and St Asaph’s workhouse.

Chapter 2

THE OUTCAST

In Stanley’s version of the story, John Rowlands and Moses Roberts were now on the run, still wearing rough workhouse clothing and identifiable to anyone searching for them. He states that they made their way through back roads towards Denbigh where Moses led them to ‘a dingy stone house near a bakery’ where a woman in the doorway recognised the boy. ‘When Mose crossed the threshold he was received with a sounding kiss, and became the object of copious endearments. He was hugged convulsively in the maternal bosom, patted on the back, his hair was frizzled by maternal fingers, and I knew not whether the mother was weeping or laughing, for tears poured over smiles, in streams. The exhibition of fond love was not without its effect on me, for I learned how a mother should behave to her boy,’ Stanley recalled.

The woman asked the boys whether they were in Denbigh on an errand – or had they run away? Moses related incidents leading to their departure from St Asaph’s and then allowed his companion to introduce himself as ‘the grandson of Moses Parry, of the Castle, on my mother’s side, and of John Rowlands of Llys, on my father’s side’.

She said she knew the family and asked if the boy planned to visit his paternal grandfather, old John Rowlands. The boy replied that he had indeed considered visiting him along with Young Moses, Uncle Thomas and his cousin, Moses Owen, who worked at a Church of England school at nearby Holywell. The woman told the boy that old John Rowlands was now a prosperous landowner, but a ‘severe, cross and bitter’ old man, unlikely to offer help. She said that the boy’s father had ‘died many years ago, 13 or 14 years, I should think’. He had, in fact, died two years before.

The following morning, the runaway grandson of wealthy farmer John Rowlands and son of the late John Rowlands, set off to visit his relatives, hoping they would take pity on him and welcome him into their home. He arrived at a large farm, stocked with well-fed animals, with an image in his mind of a severe and sour old man. He prayed it would be wrong.

Stanley recalled:

Nothing is clear to me but the interview, and the appearance of two figures, my grandfather and myself. It is quite unforgettable. I see myself standing in the kitchen of Llys, cap in hand, facing a stern looking, pink complexioned, rather stout, old gentleman in a brownish suit, knee breeches, and bluish-grey stockings. He is sitting at ease on a wooden settee, the back of which rises several inches higher than his head, and he is smoking a long clay pipe.

He asked the boy who he was, what he wanted and sat back in his seat puffing on his pipe while the boy provided answers. ‘When I concluded, he took his pipe from his mouth, reversed it, and with the mouth-piece pointing to the door, he said: “Very well. You can go back the same way as you came. I can do nothing for you, and have nothing to give you.”’

This rejection, whether it happened as Stanley relates it or at another time in his young life, remained vivid in his mind into old age. He states: ‘The words were few; the action was simple. I have forgotten a million things, probably, but there are some pictures and some few phrases that one can never forget. The insolent, cold-blooded manner impressed them on my memory, and if I have recalled the scene once, it has been recalled a thousand times.’

Later, the boy returned to Castle Row where Young Moses had become prosperous after acquiring his late father’s butchery business. His wife Kitty received the boy ‘with reserve’. He was given a meal, ‘but married people with a house full of children do not care to be troubled with the visits of poor relations, and the meaning conveyed by their manner was not difficult to interpret’.

Next he knocked at the door of the Golden Lion, a pub kept by Uncle Thomas, but there was no room at the inn for a workhouse runaway and in a last-ditch attempt to find someone prepared to give him shelter, John Rowlands made his way towards Brynford and cousin Moses Owen the schoolteacher at the new National School who lived in lodgings next door.

Cousin Moses, ‘a tall, severe, ascetic young man of 22 or 23’, was surprised by his unexpected visitor. He asked the boy questions both academic and personal and appeared satisfied with the answers. To the boy’s surprise, cousin Moses offered him a job as a classroom helper, payment to be made in clothing, board and lodging. Moses was unable to take the boy into the school immediately, so packed him off to his mother’s home at Tremeirchion, where he was told she would provide clothes suitable for a young scholar. He would be sent for the following month.

At last, it appeared as if someone was prepared to admit an ex-workhouse boy into their lives, give him a chance – and, perhaps, some affection. The following day, full of high expectations, he walked to the village and a stone house called Ffynnon Beuno, or St Beuno’s Spring, where a sign over the door told anyone who could read that Mary Owen owned the house and was licensed to sell groceries, tobacco, ‘ale and spirituous liquors’. As he knocked on the door, the boy offered up a silent prayer that his aunt would be as gracious as her schoolmaster son seemed to be.

A woman with ‘a bony and narrow face’, who turned out to be Aunt Mary, opened the door and the boy handed over his letter of introduction scribbled by her son the previous evening. Its contents appeared both to surprise and annoy her and the boy felt she would rather not have received the news that he had come to stay.

In between serving ale and groceries to customers, Aunt Mary plied the boy with questions. Later, he overheard snatches of conversations with patrons and most were about how rash, extravagant and stupid her son Moses had been, offering this strange new boy in workhouse clothes a job and shelter in her home.

In return for board and lodgings, young John helped his aunt around the shop and farm. Over the following weeks he ‘had abundant opportunities to inform myself of the low estimate formed of me by the neighbours’. By eavesdropping on conversations between men drinking his aunt’s home-brewed ale, he learned he was the son of Aunt Mary’s youngest sister, Elizabeth, also known as Betsy, now mother of three other children who ‘had thereby shown herself to be a graceless and thriftless creature’.

Soon the boy also discovered that his situation at the house-cum-shop-cum-pub at Ffynnon Beuno was little better than he had endured at St Asaph’s. To her four sons, Aunt Mary was the best of mothers, but her sister’s young bastard she kept at arm’s length until the requisite month had passed and the next part of the boy’s life was to begin at the National School.

Wearing his first suit of smart school clothes, John Rowlands was driven to the school by his aunt in her pony and trap and the following day was appointed an assistant to his cousin who was in charge of the second class. He discovered that in some subjects, other boys were more advanced in their knowledge, but in history, geography and composition, young John Rowlands was best in the school. During evening hours, he was encouraged to study Euclid on geometry, algebra, Latin and grammar. He was allowed to read books from the school library and during weekends spent most of his waking hours engrossed in adventurous literature. The boy found it difficult to make friends. During his first few days at Brynford, boys learned ‘of my ignoble origin’ and workhouse background, resulting in taunts, jibes and social exclusion.

Although only in his early twenties, cousin Moses was a hard taskmaster, finding much to criticise in young John’s efforts. ‘With every spoonful of food I ate, I had to endure a worded sting that left a rankling sore. I was a “dolt, a born imbecile, and incorrigible dunce”. When the tears commenced to fall, the invectives poured on my bent head. I was “a disgrace to him, a blockhead, an idiot” . . . and [he would] say: “I had hoped to make a man of you, but you are bound to remain a clodhopper; your stupidity is monstrous, perfectly monstrous . . . your head must be full of mud instead of brains. You must go back whence you came. You are good for nothing but to cobble pauper’s boots.”’

The boy’s self-esteem plummeted. A long period of inactivity at the school had made him plump with a round face and rosy cheeks, which made him a target for more cruel jibes from students. Despite his academic achievements, the boy received no encouragement or praise from cousin Moses.

The violence began all over again. When Moses, wearing his ‘kill-joy mask’ ran out of spiteful words to hurl at John’s head, he reached for a birch, boots or anything else that came to hand and hurled them towards his young relative. After nine months of verbal and physical abuse, the lad returned to Ffynnon Beuno for a long weekend, never to return to the National School. He helped on the farm and in the shop under the stern and watchful eye of Aunt Mary, always in the habit of reminding her nephew he would ‘shortly be leaving’.

Quite where young John Rowlands would be going and with whom was never mentioned. He was encouraged to apply for a job as a platform assistant at Mold railway station, but nothing came of it, and Aunt Mary urged him to write to his Uncle Tom Morris and Aunt Maria in Liverpool to ask if they might find him suitable employment. Shortly afterwards, Aunt Maria arrived and told Aunt Mary that there was plenty of work to be found in the city and that her husband, Uncle Tom, had influence with the manager of an insurance company. The boy’s future as an office assistant was assured.

As the packet steamer carried the boy and Aunt Mary towards Liverpool and the coastline of North Wales disappeared from view, young John ‘was astonished to see dozens of huge ships sailing, under towers of bellying canvass, over the far reaching sea, towards some world not our own’. In his tin trunk was a new Eton suit paid for by his aunt, an overcoat and little else. Soon, the smoke-filled horizon of Liverpool came into view and, as they approached, the boy saw a mass of houses, tall chimneys, towers and groves of ships’ masts stretching as far as the eye could see.

They disembarked and boarded a public carriage that drove past berths where docked the scores of ships that sailed in and out of one of the world’s largest seaports. The air was acrid with the fumes of pitch and tar and the noise from the horse-drawn traffic that bumped along the street was deafening. For a boy who had spent the first fifteen years of his life in the quiet of the Welsh countryside, Liverpool’s clash and clamour came as a surprise.

The carriage stopped outside a hotel, where Aunt Mary handed the boy over to Aunt Maria who was waiting at the entrance. Aunt Mary could not stay; she had to return to Ffynnon Beuno, her business and customers. Reaching into her bag, she pulled out a sovereign and pressed it into John Rowland’s hand. She told him to be a good boy and make haste to get rich. Then she was gone.

Aunt Maria ushered the boy into another cab and told the driver to head towards Roscommon Street in the city’s Everton district. There Uncle Tom was waiting with cousin Teddy. Suddenly the boy had acquired more of a family than he had thought possible.

Uncle Tom was a genial man who had once occupied a responsible post with a railway company. Thanks to his influence, a man called Mr Winter had secured a position with the company and this same Mr Winter was said to be the man who would arrange for Uncle Tom’s new nephew to begin a job in an insurance office. At some point, Uncle Tom had left the railway company and was now a lowly paid worker at a textile mill. Mr Winter, however, had risen to a managerial role and was in charge of an entire department. The reason why Uncle Tom toiled away at a poorly paid job while Mr Winter sat behind a large desk issuing instructions was not made clear to John Rowlands.

The boy’s first days in Liverpool were spent exploring the busy streets leading from Everton to the docks. And then the day was announced when Uncle Tom would take the boy in his new Eton suit to call on the famous Mr Winter, through whose guidance the foundations of his future prosperity would be laid. Uncle Tom told John he had befriended Mr Winter some years earlier when he had moved in more affluent circles. Then Uncle Tom’s influence had resulted in Mr Winter’s promotion and his promise to repay the favour one day – and today was that day.