13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

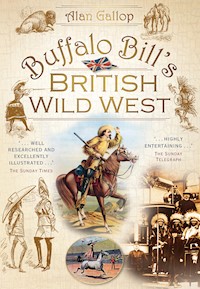

The story of how William F. Cody, army scout, Indian fighter, stagecoach driver and buffalo hunter, became an acting sensation with his Wild West show, playing to millions of people in America and Europe for over 30 years. This account highlights the tours of Victorian and Edwardian Britain. Includes details of the many towns and villages visited by Buffalo Bill and how the residents reacted to this incredible spectacular. This entertaining account of Buffalo Bill's tours of Britain is richly illustrated, with many previously unpublished photographs, cartoons, and posters.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2009

Ähnliche

Buffalo Bill’s

British Wild West

ALAN GALLOP

This book is dedicated to my family and to Major John M. Burke, first of the really great P.R. men, who blazed a trail I found easy to follow . . .

First published 2001

This edition first published 2009

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Alan Gallop, 2001, 2009, 2013

The right of Alan Gallop to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9998 7

Original typesetting by The History Press

Ebook compilation by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk

CONTENTS

Preface

Acknowledgements

Overture

A Very British Affair

ACT ONE

Scene One

Enter Buffalo Bill

Scene Two

Dime Novel Hero, Actor and ‘The First Scalp for Custer’

Scene Three

The Wild West, The Partners & ‘Little Sure Shot’

ACT TWO

Scene One

Eastward Ho!

Scene Two

‘The Yankeeries’, ‘Buffalo Billeries’ & ‘The Scalperies’

Scene Three

‘By Royal Command’

Scene Four

Heading North

ACT THREE

Scene One

Doing Europe

Scene Two

The Buffalo Bill Express

ACT FOUR

Scene One

Positively, Definitely and Perhaps the Final Farewell

ACT FIVE

Scene One

The Last Round-up

Scene Two

Postscripts and Curtain Call

Round-up of Buffalo Bill’s British Wild West Tours 1887–1904

Further Reading

PREFACE TO

YET ANOTHER BOOK ABOUT

BUFFALO BILL

I may walk it, or ’bus it, or hansom it: still

I am faced with the features of Buffalo Bill.

Every hoarding is plastered, from East-end to West,

With his hat, coat, and countenance, lovelocks and vest.

Ode to Buffalo Bill, The Globe, 1887

More books have probably been written about Colonel William F. Cody – ‘Buffalo Bill’ – than about Sir Winston Churchill, Princess Diana and President John F. Kennedy put together. There are hundreds of them if autobiographies, biographies, personal reminiscences, ‘dime’ novels, story and comic books produced in America and Britain between 1869 and 1959 are taken into account. So why the need for another?

Factual books about Cody’s life usually focus on Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, his brilliant recreation of life and scenes from America’s vanishing frontier, which played to millions of people in America and Europe for over 30 years. Apart from an occasional chapter or short reference, however, little detailed mention is made of Cody’s four tours of Victorian and Edwardian Britain with his company of cowboys, Indians,* western girls and ‘rough riders of the world’. The story of his adventures with Kings, Queens, commoners and the not-so-common in an alien country deserves to be told in depth, with the American section of his life taking second place for once.

Amazingly, many of today’s Americans have never heard of Buffalo Bill. British people – and until recently I was one of them – believe Cody to be a fictional character from television, cinema or comics; someone like Clark Kent, Sherlock Holmes, James Bond or a person whose life was given the Hollywood treatment and re-written for entertainment (which has certainly been the scenario in Cody’s case, thanks to the way his own life was chronicled in print and on the silver screen).

I bumped into Buffalo Bill by accident in a public telephone booth at London’s Earls Court. After dialling a number and waiting for an answer, I looked above the call booth, searching for nothing in particular. My eyes fell on a metal wall plaque carrying an engraving of a man with a goatee beard, long hair and wearing a large hat. Before the number was answered, I had a chance to read:

‘Buffalo Bill’s Wild West opened at Earls Court, May 9 1887 – the first appearance of the Wild West outside of the American continent coincided with Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee . . .’ The ringing stopped and the call was answered – but by now I was intrigued and told the person at the end of the line that I would call back later. I replaced the receiver and read the rest of the plaque:

‘. . . the show was so well received it remained for over 300 performances – two of them “command performances” for Queen Victoria.’

The plaque went on to explain the origins of the show in North Platte, Nebraska in 1882 and how Cody had become ‘a symbol of the most glamorous and colourful era in US history. He literally created and shipped a sample of the “old west” to centres of population around the world, giving millions of Americans and Europeans an opportunity to view at first hand a part of American history that had captured the popular imagination.’

The information on the plaque was enough to send me away wanting to know more and Buffalo Bill’s British Wild West is the result of that research. Few books by or about Cody are currently in print in Britain and the United States. Newspaper archives, however, are full of eyewitness accounts of how he came, saw, and conquered England, Wales and Scotland during the time of Queen Victoria, King Edward VII and the great days of the old British Empire. To gather material for this book I have referred to over 800 different British, Welsh and Scottish newspapers and magazines from those periods and examined numerous personal letters, journals, private papers and official documents in private and public collections on both sides of the Atlantic. As a result, much of the story told in this book about Buffalo Bill and the people he came into contact with appears in print for the first time.

For readers ‘new’ to Buffalo Bill – and I expect that to be many – I have included sections about his life in America, before, between and after the British tours. To appreciate Cody the man, his private and public persona, his successes and failures, it is necessary to fill the gaps between in order to bring him back to life once again on the following pages.

Finally, some terms and sources used in the book. In describing the Native Americans who travelled across Europe and America with Buffalo Bill, I have frequently resorted to use of the traditional ‘Indians’, although I am of course aware that, particularly in the United States, this term nowadays tends to give some offence. This is not my intention; however, I was keen to preserve the historical flavour of the book. I have quoted liberally, too, from contemporary letters and newspaper articles whose patronising tone at the time was quite breathtaking. Readers need not take offence from this, but merely marvel that such attitudes could ever have prevailed in ‘liberal’ Western society. The spelling and grammar of these too have been kept as ‘native’ as my editor would allow, demonstrating that progress has also been made in the field of education over the past 100 years or so.

* Native Americans.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A great many people provided me with assistance in gathering material for Buffalo Bill’s British Wild West and I am grateful to them all, especially:

Victor Bryant, Archivist at Earls Court–Olympia, who was my first port of call for research and who set me off on Cody’s British train; Gail Cameron, assistant curator for Later London History and Collections at the Museum of London; Andrew Kirk at the Theatre Museum; Mr Michael Bayley of Maidenhead, Berkshire, Mr Jim Carey of Slough, Berkshire, and Mr Roger Partridge of Surbiton, Surrey, who generously shared their family Cody memorabilia with me; Mr Bryan Mickleburgh, a talented artist and western historian of Hadley, Essex for allowing me to examine and reproduce documents about The Buffalo Bill Line; Pamela Clark at the Royal Archives Collection Trust at Windsor Castle for providing me with material from Queen Victoria’s private journals; Hugh Alexander at the Public Records Office Image Library, Kew; Mr Nate Salsbury of New Bern, North Carolina, for information about his grandfather; Eleanor M. Gehres and Kathy Swan at the Denver Public Library (Western History/Genealogy Department); Julie Logan and the Darke County Historical Society at the Garst Museum, Greenville, Ohio, and Bess Edwards, President of the Annie Oakley Foundation, Greenville, Ohio, for material on Annie Oakley; Susan Brady at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University for material on Nate Salsbury; Steve Friesen at the Buffalo Bill Museum at Lookout Mountain, Denver, Colorado for material on Johnnie Baker; Sam Maddra of Glasgow University and Maire Noonan of the Art Gallery Museum, Kelvingrove, for material on Glasgow’s ‘ghost dance’ shirt; Robert Hale Ltd for allowing me to reproduce an excerpt from Godfrey James’s book London – the Western Reaches (1950); my enthusiastic editors at Sutton Publishing, Jane Crompton and Paul Ingrams, whose ideas about style and design have contributed a great deal to ‘the look’ of the book; Barry J. Hughes for his enthusiasm, total support and belief in this book and last – but not least – the fantastic, always helpful and enthusiastic staff at the British Library’s Newspaper Library at Colindale, London NW9, without whom . . .

Overture

A VERY BRITISH AFFAIR

Well, Eighty-Seven at last then is here,

The Year of Rejoicing, the Jubilee Year!

Omens of peace, may they find full fulfilling!

With loyal good will every bosom is thrilling.

Everyone hopes an irradiant Gloria

May shine on the Fiftieth Year of Victoria.

Punch, January 1887

Britain was full of expectation during the early months of 1887. Her Majesty Victoria, Queen of Great Britain and Ireland and Empress of India had been on the throne for half a century – most of that time spent out of the public spotlight in mourning for her husband and consort, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, who died of typhoid in 1861, aged 42.

Mounting pressure from politicians, the press and public had forced the 68- year-old monarch to take a more public role in life again, something she reluctantly agreed to do on the occasion of her Golden Jubilee in 1887.

It was decreed that the entire year marking one of the greatest reigns in history would be one of celebration, climaxing in festivities and public holidays. It would include street parades through London, with Victoria herself in a carriage as its centrepiece – the first time she would be seen by so many subjects for over 25 years. There would be a Thanksgiving Service at Westminster Abbey, picnics, parties, grand balls, sporting and artistic events plus an extended holiday weekend during the month of June offering a chance for some fun.

Most of Europe’s crowned heads, along with Presidents, Prime Ministers and potentates from large and small nations, planned to be in London for the Jubilee. Half of Europe’s crowned heads already claimed connections with Queen Victoria through marriage, so the presence of Kings, Kaisers, Emperors, Queens, Princes, Princesses, Marquises, Grand Dukes and their equally Grand Duchesses was assured. A visit to London in June 1887 would demonstrate their close ties with Britain and allegiance to the most powerful nation on earth.

Victoria’s Jubilee was to be a very British affair. Foreigners were welcome to attend, witness, and marvel – but only from a distance. The event was a celebration of everything British; industrial power, artistic achievements, military victories and Imperial domination. It was an opportunity for the rest of the world to pay homage to the lady who had been dubbed ‘the widow of Windsor’ and who sat at the head of an Empire of tens of millions, most of whom would never see the plump little woman in black sitting on her golden throne.

But there was an exception. Without seeking anyone’s official permission, the United States of America announced its intention to send a large delegation to the festivities. Britain’s ‘American cousins’ planned to celebrate the Jubilee in a unique way, giving tens of thousands of Britons flocking to London for the event a special transatlantic treat.

Supported by a large body of influential politicians and businessmen (including Lord Randolph Churchill and his American-born wife, Jennie), the event was to be a showplace for America’s own achievements, inventions and resources. It was designed to demonstrate that the Yankees were every bit as good – perhaps better and even more advanced – than the British.

London was told to prepare itself for ‘a six-months long celebration of America and its achievements . . .’

What the Americans planned for London was a unique ‘American Exhibition’ right in the heart of Britain’s capital, showing off everything that they claimed to lead the world with at the time. It was set to rival Prince Albert’s own Great Exhibition of 1851, held in Hyde Park.

The American Exhibition was to be more than a trade fair presented by enterprising sellers for potential buyers. Entertainment, attractions, music, fine arts, food, drink and fun would also surround what the Illustrated London News predicted would be ‘a complete collection of the productions of the soil, and of the mines and the manufactures of the United States, than has ever yet been shown in England at any international exhibition.’ London was told to prepare itself for ‘a six-months long celebration of America and its achievements, transplanted three thousand miles from the New World into the heart of an old one.’

News about the American Exhibition was enthusiastically received. The Illustrated London News reported:

. . . it is an idea worthy of that thorough-going and enterprising people. We frankly and gladly allow that there is a natural and sentimental view of the design, which will go far to obtain for it a hearty welcome in England. The progress of the United States, now the largest community of the English race on the face of the earth, though not in political union with Great Britain, yet intimately connected with us by social sympathies, by a common language and literature, by ancestral traditions and many centuries of a common history, by much remaining similarity of civil institutions, laws, morals, and manners, by the same forms of religion, by the same attachment to the principles of order and freedom, and by the mutual interchange of benefits in a vast commerce and in the materials and sustenance of their staple industries, is a proper subject of congratulation . . . And we take it kindly of the great kindred people of the United States, that they now send such a magnificent representation to the Fatherland, determined to take some part in celebrating the Jubilee of Her Majesty the Queen.

The publication stated that the idea for an American Exhibition had been three years in the making, and: ‘after much thought and toil and the expenditure of many thousands of pounds, at length it assumed a definite shape . . . And Londoners and visitors from the country will be able to enjoy the results, in what promises to be one of the greatest, most original, and most instructive of similar Exhibitions.’

Advance information published in other British newspapers also revealed that the sole imported Jubilee event would include something called:

The British would take the American hero to their hearts for the next 17 years

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Exhibition . . . The preparations for this unique entertainment have been very extensive; they were made under the supervision of Major J.M. Burke, general manager of the Wild West. This remarkable exhibition has created a furore in America, and the reason is easy to understand. It is not a circus, nor indeed is it acting at all in a theatrical sense; but an exact reproduction of daily scenes in frontier life, as experienced and enacted by the very people who now form the Wild West Company . . . It could only be possible for such a remarkable undertaking to be carried out by a remarkable man; and the Hon. W.F. Cody, known as ‘Buffalo Bill,’ guide, scout, hunter, trapper, Indian fighter and legislator is a remarkable man. He is a perfect horseman, an unerring shot, a man of magnificent presence and physique, ignorant of the meaning of fear or fatigue; his life is a history of hairbreadth escapes, and deeds of daring, generosity, and self-sacrifice, which compare very favourably with the chivalric actions of romance, and he has not been inappropriately designated the ‘Bayard of the Plains’.

This and other articles provided British newspaper readers with their first encounter with the name of Colonel William Frederick Cody – ‘Buffalo Bill’ – although readers of cheaply produced ‘dime’ novels published in America and exported to Britain needed no introduction. The British would take the American hero to their hearts for the next 17 years and remember him fondly for generations afterwards. Cody was already a household name in America, a dime novel superstar, heroic actor playing himself in theatricals about fighting savage Indians, a frontiersman, army scout and buffalo hunter.

Now he was coming to London in the role which had made him so famous at home, as a showman reproducing life in America’s untamed west for folks living in the civilised east who had never seen genuine Indians or hard-living cowboys, ridden a stagecoach, witnessed sharpshooters in action or thrilled as a bronco buster hung on for life to the back of a wild mustang. Throughout the late Victorian and Edwardian era, he would imspire Punch cartoons, a souvenir industry and possibly some of the worst poetry ever written.

John Robinson Whitley, President of the American Exhibition, said that Buffalo Bill was: ‘every bit as much a genuine product of American soil as Edison’s telephones and Pullman’s railway cars.’

But who exactly was William Frederick Cody and was the excitement surrounding him really worth all the fuss?

Act One Scene One

ENTER BUFFALO BILL

Strike the tent! The sun has risen,

Not a vapour streaks the dawn,

And the frosted prairie brightens

To the eastward, far and wan.

Prime afresh the trusty rifle,

Sharpen well the hunting spear,

For the frozen earth is trembling,

And the noise of hoofs I hear.

‘Buffalo Hunting Song’ from More Adventures with Buffalo Bill

THE GENUINE ARTICLE – WILLIAM F. CODY’S BIRTH AND BOYHOOD – A HOSTILE INDIAN ENCOUNTER – BOY WONDER OF THE PONY EXPRESS – ‘A DISSOLUTE AND RECKLESS LIFE’ – STAGECOACH DRIVER – MISS LOUISA FREDERICI – HEADING WEST WITH ‘WILD BILL’ HICKOCK – GEORGE ARMSTRONG CUSTER – ROME IS (ALMOST) BUILT IN A DAY – BUFFALO HUNTING FOR THE KANSAS PACIFIC RAILROAD – CHIEF OF SCOUTS – THE BUFFALO BILL ‘LOOK’

The man known to millions as ‘Buffalo Bill’ was a genuine western article. He was named William Frederick Cody and born near the Mississippi in LeClair, Scott County, Iowa, on 26 February 1846 to Isaac and Mary Ann Cody. Will, as he was known to his pioneering parents, was the couple’s fourth child. Four more followed. The first six years of his life were spent on his parents’ farm, ‘Napsinekee Place’ – an American Indian name.

When Will was seven, the family moved to LeClair itself before Isaac took them across the plains to the unsettled territory of Kansas, where Congress had allowed permanent settlement in Indian territory. They travelled in horse-drawn prairie schooner wagons and a carriage. The family claimed land in the Salt Creek Valley, near Fort Leavenworth, where young Will saw ‘vast numbers of white-covered wagons’ pushing on even further west towards Utah and California.

Isaac traded with Kickapoo Indians, helped survey new towns and encouraged abolitionist settlers to move to Kansas to start new lives. His outspoken anti-slavery sentiments made him an enemy of pro-slavery vigilantes. While addressing a public meeting at a Kansas general store in 1854, he was wounded in the lung during a knife attack by a pro-slavery fanatic.

The Cody home became a refuge for freedom-loving emigrants, who filled up the family house and pitched their tents in its garden. In 1857, a severe outbreak of measles and scarlet fever killed four guests. In a bid to help, Isaac ran from one tent to another in freezing rain, doing what he could to assist the sick. He caught a severe chill which, combined with after-effects from earlier injuries, eventually killed him.

Mary Ann was now left alone to raise seven children – older brother Samuel having died after a riding accident at the age of 12 in 1852. At age 11, Will became head of the Cody household and its main breadwinner. Young Will learned to ride farm horses and by age eight he owned two ponies – ‘Dolly’ and ‘Prince’ – which his father had bought during an expedition in which the young child had his first experience camping out, sleeping under the stars and meeting native Indians who came into camp to trade furs for clothing, tobacco and sugar.

Many years later in his first autobiography, Will wrote: ‘All of these incidents were full of excitement and romance to my youthful mind . . . and which no doubt had a great influence on shaping my course in future years. My love of hunting and scouting, and life on the plains generally, was the result of my early surroundings.’ By this time, Will’s education had consisted of primitive schooling, which had taught him the basics of writing and reading, but little else. By age 11, his formal education was over for good when it fell to him to support his family by getting a job.

Mary Ann persuaded the overland freighting firm of Russell, Majors and Waddell to give her son work as a messenger carrying dispatches from the Leavenworth office to the fort three miles away. Spotting his potential and ability to handle a horse, Will’s employers gave him more important duties to perform, paying the boy a grown man’s wages ‘because he can ride a pony just as well as any man can’. He was paid $40 each month to herd cattle following wagons rolling west.

Will had his first encounter with hostile Indians before he was age 12 and claimed to have killed one in a moonlight attack on his wagon train. He could now handle a gun like a marksman. Two years later he was the ‘boy wonder’ of the Pony Express, an elite band of daring horsemen who sped mail between Missouri and California in ten days. Will’s first route was a 45-mile stretch from Julesburg, where he would ride 15 miles non-stop before exchanging his horse for a fresh one and riding onwards to the next relay station.

‘He can ride a pony just as well as any man can.’

Two months later, he was assigned a 116-mile run between Red Buttes on the North Platte to the Three Crossings of the Sweetwater River in Nebraska – dangerous Indian country. One day Will rode into Three Crossings to find his relief rider had been killed in a drunken fight. As no replacement was available, he climbed back into the saddle, rode a further 76 miles to the Pony Express station at Rocky Ridge where he passed on westbound mail and received eastbound shipments to take back to Red Buttes. The round trip was 384 miles, achieved in 21 hours and 30 minutes – the longest Pony Express journey ever made by one rider before the new telegraph service brought the operation to an abrupt halt in 1861 after less than two years.

‘Under the influence of bad whisky, I awoke to find myself a soldier with the Seventh Kansas.’

Will had now become Bill – or Billy – to his friends, who included the famous scouts Jim Bridger and Kit Carson and fellow Pony Express rider James Butler (later ‘Wild Bill’) Hickock. He remained Will to his family, to whom he returned in 1861 when his mother became ill. She died of consumption shortly afterwards. Will and sister Julia were at her side.

The two oldest Cody children were given the task of bringing up the remaining siblings, aided by Al Goodman whom Julia had married shortly before her mother’s death. Julia and Al became guardians of the remaining children, although for the rest of Will’s life, Julia became his ‘mother-sister’, and they remained in touch, even when separated by thousands of miles.

In his own words, Will now ‘entered upon a dissolute and reckless life – to my shame be it said – and associated with gamblers, drunkards, and bad characters generally . . . and was becoming a hard case.’

Will had promised his mother that he would never join the United States Army while she was alive, but within days of her death and ‘under the influence of bad whisky, I awoke to find myself a soldier with the Seventh Kansas. I did not remember how or when I had enlisted, but I saw I was in for it, and that it would not do for me to endeavour to back out.’

His 18-month spell as a soldier during the closing months of the Civil War was not distinguished, despite claims that he served as a spy gathering intelligence for the Union cause and ‘skirmishing around the country with the rest of the army’ as a private soldier.

Once out of uniform in 1865, 19-year-old Bill Cody became a stagecoach driver on a route between Kearney and Plum Creek. He had also: ‘Made up my mind to capture the heart of Miss Louisa Frederici, whom I greatly admired and in whose charming society I spent many a pleasant hour. . . . Her lovely face, her gentle disposition and her graceful manners won my admiration and love; and I was not slow in declaring my sentiments to her.’

Bill met Louisa – Lulu – while working as a hospital orderly in St Louis earlier in the year. The daughter of an immigrant from Europe, Lulu had been educated by nuns and had become a fine dressmaker. Her background and temperament were very different from the 20-year-old former cattle drover, Pony Express rider, and self-confessed ‘hard case’ now knocking on her parents’ door in St Louis!

The couple were married in March 1866 after Bill had obtained written permission from Julia and Al Goodman and given Lulu an assurance that he would quit the plains and settle into a quiet life. He later reflected: ‘From that time to this I have always thought that I have made a most fortunate choice for a life partner’. There would be later times when Buffalo Bill Cody would feel differently about the lady who had just become Mrs Cody.

Lulu and Bill’s marriage was not made in heaven – as the new bride was soon to discover when, an hour after their wedding, they left St Louis by steamboat to live at Julia and Al Goodman’s ranch upriver in Salt Creek Valley, Kansas. This would be Lulu’s first taste of country life, and she made it clear that she did not care for it.

Bill and Lulu rented a large house, which they turned into a hotel, called the Golden Rule. Reasoning behind the name was never clear, but Bill considered himself a good landlord who knew how to run a hotel, even if his own golden rule was to throw drinking parties for friends every night, dishing out free whisky and rarely charging money for rooms.

His sister Helen wrote later: ‘Will radiated hospitality, and his reputation as a lover of his fellow man got so widely abroad that travellers without money and without price would go miles out of their way to put up at his tavern. Socially he was an irreproachable landlord; financially his shortcomings were deplorable.’

The newly-weds gave up the hotel business after six months. ‘It proved too tame employment for me,’ claimed Bill. ‘And again I sighed for the freedom of the plains. Believing that I could make more money out West on the frontier than I could at Salt Creek Valley, I sold out the Golden Rule and started alone for Saline, Kansas, which was then the end of the track of the Kansas Pacific Railway, which was at that time being built across the plains.’

Bill kissed newly pregnant Lulu goodbye and headed west. Lulu stayed with other Cody family members before returning to her parents in St Louis, her first separation from Bill, who for the rest of his life never spent more than six months at a time at home with his wife.

On the way out west, Bill ran into old friend ‘Wild Bill’ Hickock, who was scouting for the government. He told Bill that more scouts were needed to help the US Army police the Arapaho, Cheyenne, Sioux and Comanche Indians who were resisting attempts to drive a railway track across their territory and onwards towards the Pacific. Bill followed Hickock to Fort Ellsworth, ‘where I had no difficulty in obtaining employment’.

That winter Bill scouted the Great Plains for the army and the following spring had his first encounter with the army’s most celebrated, courageous, impulsive and vain army officer – General George Armstrong Custer, who at age 23 was the Union army’s youngest general and famed for his daring raids behind Confederate army lines.

Custer needed a guide to escort him and ten others across 65 miles of prairie to Fort Larned and Bill Cody was given the job. The journey was made successfully and Custer offered the young scout more work whenever he wanted it. They became firm friends, although it would be some time before Bill could take up Custer’s offer. Hunting work for the railway, snaking its way across mountains and prairies at the rate of two miles a day, beckoned.

On the journey to the Kansas Pacific railhead, Bill learned of new towns springing up like mushrooms along the railway route. A man called William Rose told the young scout about a town he was thinking of laying out in a prime location to the west of Big Creek, near Fort Hays. The railroad company planned to lay tracks on its route towards California and build a depot complete with locomotive sheds, repair workshops and creating jobs for hundreds of labourers. Rose invited Bill to become a partner in the enterprise and: ‘Thinking it would be a grand thing to be half-owner of a town, I at once accepted his proposition.’ Once it was completed and populated, Cody and Rose planned to open a saloon and general store, make a mountain of money and enjoy an easy life.

‘We gave the new town the old and historical name of Rome’, wrote Bill, ‘and as a “starter” donated lots to anyone who would build on them, but reserved corner lots and others which were best located for ourselves.’

Bill sent for Lulu and shortly after arriving from St Louis, she gave birth to a daughter they called Arta. The Cody family lived in hastily built quarters at the rear of the Cody & Rose general store, which was taking shape just as hastily as the town itself.

The ancient city of Rome was not built in a day, but the new frontier railway depot town with the same name ‘sprang up as if by magic, and in less than one month we had two hundred frame and log houses, three or four stores, several saloons and one good hotel. Rose and I already considered ourselves millionaires and thought we had the world by the tail’, recalled Bill.

And so they had – until the Kansas Pacific Railroad got to hear about it. Angry at not being invited to become partners in the scheme, the railroad management announced they would build their own depot town, Hays City, a mile away from Rome. ‘A ruinous stampede from our place was the result’, remembered Bill. ‘People who had built in Rome came to the conclusion that they had built in the wrong place; they began pulling down their buildings and moving them over to Hays City, and in less than three days our flourishing city had dwindled down to the little store that Rose and I built. . . . Three days before, we had considered ourselves millionaires; on that morning we looked around and saw that we were reduced to the ragged edge of poverty. . . . Thus ends the brief history of the “Rise, Decline and Fall” of modern Rome.’

Lulu – pregnant again – and baby Arta were packed off back to St Louis while Bill reluctantly put his idea of becoming a millionaire on hold for the time being. Many more new business ideas and ‘get-rich-quick schemes’ would follow in later years. Some would be wildly successful. Others were glorious failures. But for the time being he reverted to his original plan of working as a hunter of fresh meat to feed an army of 1,200 track layers, graders, section hands and engineers slowly pushing the railway line west. Every day, construction gangs needed to be fed huge quantities of cheap, fresh meat and the vast buffalo herds roaming the plains over which the railway crossed provided the diet. The only problem was the ‘very troublesome’ Indians who made it difficult for railwaymen to get the quantities of meat required day after day.

Bill was hired for $500 per month to hunt and kill not less than 12 buffalo each day. Only the hindquarters and rump were to be brought back to camp. Because of the close proximity of Indian camps, this was considered dangerous work and buffalo hunters were expected to ride five to ten miles away from the railway track to locate herds. Only one other man driving a wagon could go along on the daily hunt for meat.

‘It was at this time that the very appropriate name of “Buffalo Bill” was conferred upon me by the road-hands. It has stuck to me ever since, and I have never been ashamed of it,’ Bill later wrote about this period in his life.

During his employment as a hunter for the railroad company – a period of less than eighteen months – Bill claimed to have shot 4,280 buffalo – 69 in one afternoon. He said that the best way of bringing the massive animals down was to ride his horse, Brigham, to the right front of a herd, shoot down the leaders with his 50-calibre Springfield rifle (nicknamed Lucretia Borgia), and crowd their followers to the left until they began to run in a circle, when he would kill all the animals required.

While the railroad companies were laying tracks between Nebraska and the Pacific, anything between 40 and 60 million buffalo roamed the plains of the United States and Canada. Indians depended on the herds for their existence, not just for food and clothing but also for hides to build their tepees, sinews for threads, horns and bones for tools and buffalo dung for fuel. The railway was responsible for buffalo destruction on a massive scale, bringing the species close to extinction, using it as a source of food for labourers and later as a means of transporting hunters and eastern-based sportsmen out west to kill them for the heads and hides. The railway also became an economical way of shipping hides east for fashionable fur hats and coats, horns for buttons and bones to manufacture fertiliser.

By the time Buffalo Bill’s Wild West was thrilling Victorian London audiences, herds had been reduced to a fraction of what they had once been. With the passing of the buffalo went the nomadic way of life of the Plains Indians who were reduced to dependence on government handouts on their reservations.

In later years Buffalo Bill himself was horrified by the destruction of the animal he had helped to wipe out in such vast numbers, unaware at the time that his contribution to their mass slaughter would almost remove the buffalo from the face of the earth. With the creation of his Wild West entertainment, Bill later became a buffalo preserver and by 1890 his herd – described in his show programme as ‘this monarch of the plains’ – was the third largest in captivity; a herd of ‘healthy specimens of this hardy bovine in connection with their instructive exhibition . . . interesting as the last of their kind’.

In 1868, a violent Indian war erupted on the Kansas plains and Bill was summoned by General Philip Sheridan to come to Hays City where he was appointed an army scout, later becoming Chief of Scouts to the Fifth Cavalry. He would eventually take part in 16 different Indian fights, be mentioned in numerous army dispatches for skill and bravery and take on the appearance of what has since become the ‘Buffalo Bill look’ – a buckskin suit trimmed with fringes and beads at the seams, broad-brimmed hat, shoulder-length hair, goatee beard and handlebar moustache.

‘When the mud is flying or the terrible rainstorms are pelting upon us, these hats are the best friends we have.’

Often Bill would also wear a crimson coloured shirt under the jacket, leather moccasins or knee-length leather boots with spurs and a huge belt with a massive buckle around his waist. As a civilian employed by the army, he could wear anything he wished. He later claimed that his famous clothing and appearance were practical for army work on the plains and in the mountains.

In May 1887 he told a reporter in London from Tit-Bits magazine:

It is the general impression of people in the east that the long hair, wide brimmed hats, huge spurs, fringed leggings and other striking accessories in a cowboy’s outfit, are worn simply for show and effect; but that impression is wrong. It was not a desire for picturesqueness that led to our ‘make up’ as it is today, although that effect has followed. Questions of necessity were the first considerations that prompted the adoption of our particular dress, from the big, cruel looking spurs to our hair like Samson’s before he was shorn. All these appurtenances may be ornamental, but their usefulness is many times greater than their ornateness.

Take for instance the cowboy’s big-rimmed hat. The fact that it has been worn without change for half a century shows that use dictated its origin and use . . . to turn wild cattle and horses in the direction you desire them to go, when the sun is scorching hot and there is a blister in every puff of wind, this great hat is much cooler than straw; when the wind is blowing the sand like hot shot in our faces we should suffer greatly but for the protection afforded our eyes by the big rimmed hat. When the mud is flying from the heels of stampeding cattle, or the terrible rain-storms of the plains are pelting upon us, these hats are the best friends we have.

As to why Bill wore his light brown hair down to his shoulders, he explained:

Our business is in the open, rain or shine, and in many changes of climate, and we have found from experience that the greatest protection for our eyes and ears is long hair. Old miners and prospectors know this well. Hunters, scouts, trailers and guides let their hair grow as a rule. Those who have been prejudiced against it have suffered the consequences of sore eyes, pains in the head and loud ringing in the ears. The peculiar result of exposure without the protection of long hair is loss of hearing in one ear, caused by one or the other ear being exposed more when the plainsman is lying on the ground. Healthy hearing and eyesight are of the greatest importance to a scout, hunter or herdsman. . . . Having found that the growth and wearing of long hair not only preserves but strengthens our sight, and makes our hearing more acute, we let nature have her way in the matter, and profit by it.

While Bill’s explanation about his appearance might have been true, few others at the time also wore tailor-made buckskins, crimson shirts, fancy belts and spent so much time on their personal grooming and appearance. Perhaps his friends ‘Wild Bill’ Hickock and General George Armstrong Custer influenced him. By the time Bill had been promoted to Chief of Scouts, Hickock was equally famous for his long flowing locks, buckskin clothing and a stylish way of wearing six-guns with handles pointing forward in the gunbelt. Custer’s hair also fell to his shoulders in ringlets. He was permitted to wear a uniform of his own design which included a velveteen jacket, trousers decorated in gold lace, a red kerchief around his neck and his hat positioned at a jaunty angle on his head.

Bill’s early clothing was custom-made for him by Lulu on all-too-infrequent visits home to see his wife and baby. Later versions of the Cody costume, however, were commissioned from top eastern tailors for his appearances with the Wild West show.

Thanks to daring deeds on the prairie, striking appearance and unconventional clothing, Bill was starting to be noticed and talked about and by 1869 he was on the eve of becoming a national celebrity.

Act One Scene Two

DIME NOVEL HERO, ACTOR AND ‘THE FIRST SCALP FOR CUSTER’

Nature’s proud she made this man,

This man Bill;

For it’s always been his plan

To help others when he can –

Kindly Bill!

During all these hard-time years

He’s been drying orphans’ tears

And relieving widows’ cares,

Has this Bill.

Often lightened hearts of lead,

Smiling Bill!

With your kind words and your bread

Both the soul and mouth you’ve fed,

Generous Bill!

An anonymous poem, sent to Buffalo Bill in 1886

NED BUNTLINE AND ‘THE KING OF THE BORDER MEN’ – DIME NOVEL HERO – BUFFALO HUNTING WITH ‘THE TOFFS’ – GRAND DUKE ALEXEI – ‘PAHASKA’ – A VISIT TO NEW YORK – AN ACTOR’S LIFE – INTRODUCING MAJOR JOHN M. BURKE – ‘WILD BILL’ BECOMES AN ACTOR – DEATH OF KIT CARSON CODY – ‘THE FIRST SCALP FOR CUSTER’

Bill claimed that he was first introduced to ‘Ned Buntline, the novelist’ by Major William Brown who told him that the storyteller – whose name was new to Bill – would be joining them on a scouting expedition into Indian territory.

Edward Zane Carroll Judson, who wrote blood and thunder stories under the pen name of ‘Ned Buntline’, had run away to sea at the age of ten and much later wrote about his experiences. As a young man he published the Western Literary Journal and Ned Buntline’s Own, full of adventure stories for easterners who could not read enough about life in the west. By 1849, Buntline had become America’s highest paid writer. With an annual income of £20,000, he earned more than Mark Twain and Walt Whitman. Now Buntline was taking a westbound train seeking inspiration for new stories for his eastern readers to devour.

Buntline was hoping for co-operation from Major Frank North, who had found fame following an episode later known as the Battle of Summit Springs. On the expedition, Bill had guided Major North and the Fifth Cavalry to a position from which soldiers could encircle and surprise Chief Tall Bull’s murderous Cheyenne warriors who had been terrorising settlers on the Kansas Plains. Two white women were being kept hostage at the Indian settlement. Major North won the credit, ably assisted by Bill who is said to have killed Tall Bull and captured his grey horse – also called Tall Bull – which he was allowed to keep and enter in local races.

Major North had no interest in talking to Buntline, and pointed across the parade ground to a wagon, under which a young man was sleeping off a hangover. The young man was 23-year-old Bill Cody, also known locally as Buffalo Bill. Buntline dragged him out, sat him in a chair, sobered him up and got him to talk about his exploits as a Pony Express rider, stagecoach driver, frontiersman and army scout.

On the following day’s expedition, Buntline heard more about Bill’s colourful life in the ‘wild west’ – which, with a few embellishments to heighten dramatic interest, became the first instalment of the serial story Buffalo Bill, the King of the Border Men in the 20 December 1869 edition of the New York Weekly.

When a copy eventually found its way back to Bill at Fort McPherson, Kansas, the star of the story was delighted and flattered by Buntline’s account of his life on the frontier. ‘Well, dog my cats!’ he is said to have remarked – an expression he used during the rest of his life whenever surprised or delighted.

At the same time as thousands of others were heading west to claim a piece of land offered by the Homestead Act of 1862, Lulu and baby Arta took a train from St Louis to join Bill at the fort. The army had agreed to build a house for their Chief of Scouts and very own storybook hero. Lulu was heavily pregnant with their second child and gave birth to a son while Bill was away scouting with the Fifth Cavalry, which was having more real-life adventures with Indians on the plains. Bill was also in demand as a leader of hunting parties made up of rich easterners and European tourists wanting to see the west, bag a buffalo head to hang from their drawing room walls and catch sight of a savage Indian or two.

Major North had no interest in talking to Buntline, and pointed across the parade ground to a wagon, under which a young man was sleeping off a hangover.

It was weeks before Bill returned to the fort to meet his new son. No name had been given to the child and Bill suggested Elmo Judson, in honour of Ned Buntline whose Buffalo Bill stories had now reached frontier readers, making Cody just as famous in his own back yard as he was in eastern cities. Officers and fellow scouts at the Fort objected to the name and it was agreed that the child be named Kit Carson Cody in honour of Bill’s famous frontier friend.

In later years, Buffalo Bill became the central character in hundreds of dime novels, the nineteenth century equivalent of today’s comic book heroes or characters in popular fiction. Following Buntline’s success with his serial story, others followed. Bill’s fame as a living fighter of real Indians and hunter of huge bison on the western plains created demand for more exciting tales. When Bill later appeared in person in plays about his exploits and his Wild West entertainment attracted millions of excited spectators, Buffalo Bill’s name was as well known in America as a top film star would be today. The public could not get enough of him.

Other writers took over where Buntline had left off. Colonel Prentiss Ingraham, later a publicist for the Buffalo Bill organisation, was responsible for over 200 dime novels with titles such as: Buffalo Bill, the Buckskin King, or Wild Nell, the Amazon of the West; Buffalo Bill’s Buckskin Braves, or The Card Queen’s Last Game; Buffalo Bill’s Sweepstake, or The Wipe-out at Last Chance and Buffalo Bill’s Sure-Shots or Buck Dawson’s Big Draw.

Buntline was surprisingly slow to capitalise on his own success. It would be some while before he wrote more serials about America’s popular frontier hero, but he eventually made a mint of money from converting his original story into a Buffalo Bill play for the theatre. He later collected his printed serials together and turned them into novels, wrote new ones and republished old stories right up until his death in the 1920s.

Although Bill had become a western storybook hero, the Cody family bills still had to be paid and there is no evidence that he received any fee for talking to Buntline and allowing his name to be used in stories. To supplement his income from scouting, Bill agreed to lead hunting parties on behalf of the military, made up of rich ‘toffs’ travelling out on new railway routes looking for wild west adventure – sportsmen, curiosity seekers and aristocratic tourists wanting to experience the thrill of the chase and shoot buffalo and wild game on the plains.

Friendly Indians were recruited to take part in expeditions and add ‘local colour’ to the frontier experience. They were called on to perform traditional songs and dances around the campfire for the amusement of the amateur huntsmen, and were well paid for their trouble. Bill also used the services of another white scout from Fort McPherson, John Nelson, who had married the daughter of an Oglala Sioux Chief. Nelson had been given the Indian name Cha-Sha-Cha-Opoyeo (or Red-Willow-Fill-the-Pipe). In later years Nelson, his squaw wife and their half-breed family, travelled across the great waters to be part of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in England.

Up to 16 supply wagons travelled with the hunting parties, one full of ice to make sure the champagne and vintage wines remained cold.

Hunting parties provided Bill with the extra income he needed to support his family, which had grown again with the birth of a second daughter called Ora Maude. As the Buffalo Bill legend began to grow, rich and influential easterners began asking for him by name. Hunting parties included the English Earl of Dunraven, James Gordon Bennett of the New York Herald, Charles L. Wilson of the Chicago Evening Journal plus wealthy eastern and mid-western sportsmen, business tycoons and Russia’s Grand Duke Alexei. They all called on the army to give them a chance to hunt buffalo on frontier safaris with the famous Buffalo Bill as their guide.

The sporting ‘toffs’ also paid for the privilege of going out on army scouting patrols and living the life of a frontier soldier – only their overnight accommodation and catering arrangements were worlds apart from the meagre rations and crowded tents experienced by the average trooper. Up to 16 supply wagons travelled with hunting parties, one full of ice to make sure the champagne and vintage wines remained cold. Another was crammed full of starched white linen, bone china, silver tableware and cut glass for multi-course dinners prepared by imported French chefs and served by waiters in evening dress. Life out west for a rich toff was often hard indeed. . . .

Bill soon discovered how to enjoy a champagne lifestyle. He acquired a taste for fine wines, rich food and influential company. All that were asked in return was plenty of dead buffalo for sportsmen to claim as their own at the end of the day. One party bagged over 600 buffalo and 200 elk – blazing a 194-mile-long trail of empty champagne bottles behind them.

The army agreed to host the frontier safaris to generate goodwill and favourable publicity for servicemen and officers stationed hundreds of miles away from civilisation. Newspaper stories about the hard life of a frontier soldier encouraged Washington politicians to appreciate how tough life in the west really was.

Stories about western hunting parties were eagerly followed in the east through dispatches cabled to newspaper offices in New York and Chicago. Thanks to these stories, people learned more about life on the plains ‘guided by the renowned and far-famed Buffalo Bill’. His reputation and legend among influential easterners was starting to soar.

Some ‘toffs’ were good shots who managed to bring down buffalo with one or two shells. Others were not so skilled with weapons, including Grand Duke Alexei, fourth child of Russia’s Tsar Alexander II, who was visiting America on a goodwill tour in 1872. After arriving in the United States with a Russian naval fleet as his escort, Alexei was given VIP treatment in New York and Washington. The young Grand Duke then announced that instead of returning home to St Petersburg, he wanted to travel west and participate in the first ‘Royal Buffalo Hunt’ ever to take place in the United States – with Buffalo Bill as his guide.

Bill’s old friend General Philip Sheridan was given the task of making sure the Grand Duke’s every need was catered for. He instructed Bill to mobilise the army and create ‘Camp Alexei’, a comfortable base for the hunt. Bill was also told to track down Spotted Tail, a Sioux Chief, and persuade him to send 100 Indians to put on a show for the Russian guest. Sheridan wanted the royal buffalo safari to be a spectacular entertainment – no expense was to be spared.

Chief Spotted Tail, not involved in hostilities with white men at that particular time, said he would be pleased to join ‘Pahaska’ (the name the Sioux had given Bill – it means ‘long hair’) and welcome another ‘great Chief from across the water’. Meanwhile, at Red Willow Creek, 40 miles away from the fort, troops were busy constructing ‘Camp Alexei’, complete with elaborate tents with wooden floors, carpets, pot-bellied heating stoves and fine furnishings shipped in by train from Chicago.

The special train carrying Alexei and a host of US Army top brass – including Custer and Sheridan – arrived at the camp to be met by a welcome party headed by Bill, Chief Spotted Tail, 100 Indian braves and a company of uniformed cavalry. The entire caravan immediately took off for the camp where a grand dinner was laid on and a fireside war dance cabaret was provided by the Sioux.

Next morning, protocol dictated that the first buffalo of the day be brought down by the Grand Duke, who chose to use a revolver. However, it soon became clear that Alexei was unable to hit a barn door from inside with the doors closed, let alone a giant buffalo. Bill had loaned Alexei one of his own horses – Buckskin Joe – and once the Russian had wildly emptied his pistol without success, rode up alongside the Grand Duke and passed him another fully loaded weapon. Again, Alexei missed every shot.

Bill takes up the story:

Seeing that the animals were bound to make their escape without his killing one of them, unless he had a better weapon, I rode up to him and gave him my old reliable Lucretia and told him to urge his horse close to the buffaloes, and I would then give him the word when to shoot. At the same time, I gave old Buckskin Joe a blow with my whip, and with a few jumps, the horse carried the Grand Duke to within about ten feet of a big buffalo bull. ‘Now is your time,’ said I. He fired and down went the buffalo. The Grand Duke stopped his horse, dropped his gun on the ground, and commenced waving his hat. Very soon the corks began to fly from the champagne bottles in honour of the Grand Duke Alexei, who had killed the first buffalo.

Thanks to rich ‘toffs’ and the Grand Duke Alexei, Buffalo Bill had begun producing his first Wild West shows.

Later that day Alexei killed a buffalo cow with his pistol and more champagne was opened. ‘I was in hopes that he would kill five or six more if a basket of champagne was to be opened every time he dropped one,’ noted Bill.

Thanks to Bill’s skill and patience – and some gentle urging from Custer and Sheridan – Alexei managed to drop a further six buffalo by the time the five-daylong safari ended. Alexei was allowed to hunt with Spotted Tail’s braves, seeing at first hand how they used a bow, arrow and lance to kill their prey. The Russian was thrilled with himself and sent a mountain of buffalo hides and trophy heads back to St Petersburg to display in his grand palace.

Before leaving, Alexei summoned Bill to his private carriage, where he presented his new American frontier-friend with some generous gifts – a large patchwork robe made from 57 different rare Siberian furs, a Russian fur coat and hat. Alexei also commissioned a pair of diamond-studded buffalo cufflinks and a tiepin to be specially made, which was sent to Bill as a farewell gift. Thanks to rich ‘toffs’ and the Grand Duke Alexei from Russia, Buffalo Bill had begun producing his first Wild West shows.

It was time for Buffalo Bill to be seen in person in the east and, in February 1872, he took 30 days’ leave of absence to accept an invitation from a New York newspaper to visit the city. The army gave their Chief of Scouts free railway passes, the newspaper’s editor cabled $500 for expenses and Bill was off to see the great city for himself, wearing the handsome fur coat given to him by Alexei.

He travelled via Chicago, where some hunting friends took him to a number of ‘swell dinners’ and a grand ball where he: ‘Became so embarrassed it was more difficult for me to face the throng of beautiful ladies, than it would have been to confront a hundred hostile Indians. This was my first trip to the east and I was not accustomed to being stared at.’

In New York, Bill stayed at the Union Club, where the newspaper’s editor and his influential friends gave their frontier guest a welcome reception and freedom to roam around the city on the Hudson: ‘Everything being new and startling, convinced me that as yet I have seen but a small portion of the world.’

Bill received so many invitations and letters from well-wishers wanting to show him a good time in New York that he accepted everything, disappointing many by failing to show up. Some invitations stipulated that he should attend in his buckskins, so keen were the eastern hosts and hostesses to see ‘the real Buffalo Bill’.

One of the people Bill wanted to seek out in New York was Ned Buntline, who lived in a stylish town house. Buntline had dramatised one of his Buffalo Bill stories, Buffalo Bill, the King of the Border Men and wanted to take his hero to a performance at the Bowery Theatre, where the actor J.B. Studley was playing the role of Bill.

Bill and Buntline watched the play from a private box. ‘I was curious to see how I would look when represented by someone else,’ remembered Bill, who was surprised to see the theatre full, with standing room only.

On learning that the genuine article was present in person in the theatre, the audience ‘gave several cheers between acts, and I was called on to come out on to the stage and make a speech’ [and meet the actor playing the title role]. ‘I finally consented, and the next moment I found myself standing behind the footlights for the first time in my life. I looked up, then down, then on each side, and everywhere I saw a sea of human faces, and thousands of eyes all staring at me.’

Bill attempted to make a speech: ‘And a few words escaped me, but what they were I could not for the life of me tell, nor could anyone else in the house. . . . I confess that I felt very much embarrassed – never more so in my life – and I knew not what to say . . . and, bowing to the audience, I beat a hasty retreat.’

Bill fled from the theatre pursued by the manager who called to the retreating figure in buckskins that he would pay him $500 a week to play the role of ‘Buffalo Bill’. Bill kept running, shouting back that he was no actor and was afraid of crowds. The play continued to be a success in New York and later toured other cities across the country.

Bill Cody continued to have a grand time in New York and sent a cable to the army asking for his leave to be extended by another ten days. The army agreed, and Bill continued having fun, seeing more plays with Buntline and talking to reporters about life out west.

No sooner was Bill back on a train to Fort McPherson, than Buntline had picked up his pen again to produce another serial for the New York Weekly –