Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

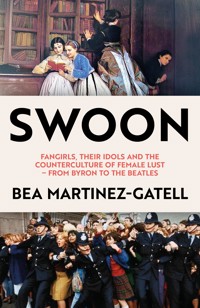

Swoon is a prehistory of the fangirl. From the Byromaniacs of Regency London to the screamers of Beatlemania, it revisits six defining moments in book, film and music history through the eyes of the girls and women who gave birth to pop culture as we know it today. Far from passive consumers, these women were tastemakers, visionaries and cultural disruptors. Their obsessions shaped literary canons, built Hollywood icons and turned musicians into messiahs – long before social media came along. But with power came panic, especially when female fans and male stars were involved. Fandom became a moral and cultural battleground. What was at stake was women's right to want things they weren't supposed to want, feel things they weren't supposed to feel and express all these things loudly, shamelessly and in public.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 559

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

“Stunningly original. Swoonreads like a novel, a pop culture history and a feminist manifesto rolled into one. Like Greil Marcus – but sexier.”

Graham Coxon, Blur guitarist and author ofVerse,Chorus,Monster!

“A groundbreaking study of female love – and lust – from Byron to the Beatles. Right from the first page, Bea Martinez-Gatell hooks you in with sensational stories of scandal but then unfolds a serious message. The policing of women’s desire, Swoonargues, says so much more about us, the society we live in and our fears of feminine sexuality than it does about the individuals involved. What a pleasure it is to read something that takes women’s pleasure seriously!”

Dr Kirsty Sedgman, cultural studies expert and author ofOnBeingUnreasonable

“With wit, precision and empathy, Bea Martinez-Gatell fever-charts the evolution of passionate female fandom – the swoon – and playfully (but wisely!) breaches the facades of the objects of desire who provoked and stoked it.”

James Kaplan, author ofFrank: TheVoiceandSinatra:TheChairman

“Swoonwon’t just sweep you off your feet – it will make you think and laugh, too. Finally, a book that takes fangirls as seriously as we deserve!” ii

Zan Romanoff, author ofBigFan

“Though the fangirl has been derided and dismissed by the male press and mainstream culture for 200 years, her passion and persistence created the brightest stars in the celebrity galaxy. Bea Martinez-Gatell’s Swoonis a fascinating cultural history of fangirls and their enormous yet overlooked impact on pop culture and beyond.”

Dr Candy Leonard, author ofBeatleness:How the Beatles and TheirFansRemade theWorld

“An enthralling and revisionist history of modern celebrity, shifting our attention from the usual cast of culture heroes to their female fans. Bold in its transatlantic and transhistorical reach and written with real passion and authority, Swoonshows how these frequently disparaged women and girls have challenged expectations around gender and art and pushed for social change. From Byromania to Lisztomania to Beatlemania, these are voices and stories that continue to resonate.”

Dr James Grande, literary scholar and editor ofThe Keats-ShelleyReview

“Tender, hilarious and profoundly moving, Swoonreveals the fascinating and often complex relationship between artists and audiences through the ages. This is a page-turning history of love, lust, fandom and cultural change that reminds us of what it means to be human.”

Cristina Cordero, Cuarteto Casals violist

iiiiv

v

She gazed in wonder, ‘Can he calmly sleep, While other eyes his fall or ravage weep? And mine in restlessness are wandering here – What sudden spell hath made this man so dear?’

– Lord Byron,The Corsairvi

Contents

Preface

Ridiculed, derided and brushed into the margins of history, the fangirl has had many names. Today, she might be a Swiftie, an Arianator or just plain Stan. At the turn of the twentieth century, she was the Matinee Girl, shamelessly swooning and weeping in the stalls of the Edwardian theatre. Her hero was the Matinee Idol – the dashing star of romantic melodramas and musicals. ‘Usually she is in bunches,’ wrote one critic, ‘two or three in a crowd, and invariably she is noisy. All through the play one hears snatches of conversation such as: “Isn’t he just darling!”, “I think he’s the most handsome man I ever saw.”’1

Theatre critics were not impressed. Forcing audiences to consume increasing amounts of ‘dramatic saccharine written to appeal chiefly to the limited intelligence of immature girlhood’ was having a damaging effect on the theatre, they said.2 And as I sit writing the final pages of this book two days before Christmas 2024 and thousands of TikToks scattered with pink glitter and heart emojis transform Ivy League valedictorian turned alleged CEO killer Luigi Mangione into a thirst trap, inappropriate adoration is still making headlines: ‘Why is the world swooning over an alleged killer?’ The historical hotties in this book are not murderers, but nearly all of them provoked a fusion of bafflement and concern when the girls xstarted swooning in their days. The Matinee Girl may well have been labelled the most harmful influence on the American theatre of 1907, but there was no denying the power of her pocketbook or the potential influence of her daydreams.

I’ve been studying fangirl history since I arrived at university as an excitable, newly feminist film and literature student still recovering from an acute case of Leomania in the early 2000s. I was surprised to be informed, in my first ‘film, gender and identity’ class, that the gaze was male. If the gaze was male, then what were all those Titanic posters for? Two DiCaprio dissertations (filled with important photos required for academic purposes) later, I graduated and the Romeo + Juliet posters came down. The Jean-Luc Godard ones went up, eventually to be replaced by pretentious abstract art prints in proper frames. As my interests and obsessions changed, so did the fangirl. She had a name now. And a verb: people were fangirling about everything from Donald Trump to ice cream. The internet had pushed her so far into the mainstream that I’d almost forgotten about looking back – until Baz Luhrmann released his 2022 Elvis biopic. How could the man who had given the wonder and beauty of Leo and Claire Danes falling in love through a fishtank to the fangirls of the ’90s have done this to the Elvis girls of the past!?

Luhrmann’s Elvis is a story we know well: handsome male genius unleashes his sexual magnetism on the world and women lose their minds. In Elvis’s first concert scene in Luhrmann’s film, girls begin involuntarily releasing monstrous otherworldly screams as he shakes those famous hips for the first time. They look both ecstatic and terrified, as if they don’t understand what it is they’re feeling, let alone doing. Soon they’re up and out of their seats like zombies rising from the dead, grabbing at our hero as he backs away from them in terror. ‘Are you trying to kill my son!?’ screams his ximama. In line with countless male star mythologies, the fangirl in this film is either a sexually aggressive monster or a vapid, clueless idiot. It’s Elvis’s divine genius that makes him a star, not the power (and pocket money) of his largely female early fanbase. By the time I walked out of the cinema, I had decided it was time to write this book.

From Frank Sinatra in the 1940s to Robert Pattinson or Harry Styles more recently, many of the biggest male stars in pop culture past and present built their early careers on their romantic appeal to young women. The dreamy swooning teenager gazing at pictures of her idol in magazines or screaming in hordes at a pop concert is a stock character in the textbooks of fame. And yet no history book has, until now, told her story from the start. Is it because she’s too trivial? Someone in publishing once advised me it might be better off as a blog post (‘Are you sure there’s enough material to fill a whole book?’). Too repetitive perhaps? Apart from the outfits, and the guy signing autographs, is there really a difference between one hysterical crowd of screaming, crying, grabbing girls in 1844 and another in 1944? Or is it because we’re still bound by centuries-old assumptions about which audiences – and which feelings – deserve to be taken seriously?

When I sat down to begin researching this book, I was looking forward to a joyfully lovestruck exploration of early movie, music and book culture. The plan was to look at the six moments in pop culture history when fangirl ‘manias’ erupted most fervently around a particular star – I’m sure you can guess a few. These were superficially heterosexual fandoms in which the male stars’ success was thought to be founded on their romantic appeal to young women – a phenomenon that was seen as both troubling and ridiculous. Very often, these men – like Elvis, Frank Sinatra and of course the xiiBeatles – went on to shed their dreaded initial ‘teen idol’ status and be reborn as some of the most iconic artists of all time. The fangirl has always been a footnote in their stories; a stepping stone on her idol’s road to later, more ‘serious’ stardom. I wanted to use this book to take the ‘not serious’ phase seriously. What was it about these stars, in their early days, that elicited such passionate, all-consuming devotion from their fans and how did these swoonish beginnings shape the ‘more serious’ artistry to come?

What I discovered was that these stories had both everything and nothing to do with the men at the centre of them. These were six moments in history when gender and society themselves were going through seismic moments of change. Who we choose to swoon about is as much, if not more, about us and the times we live in as them. Behind every swoon and every squeal, the seeds of a revolution were stirring.

Fans are everywhere these days, and their cultural and economic power is undeniable (just ask Taylor Swift), but in the earliest days of celebrity and pop culture, polite society was at first confused and then concerned – especially when female fans and male stars were involved. Fandom became a moral and cultural battleground. What was at stake was women’s right to want things they weren’t supposed to want, feel things they weren’t supposed to feel and express all these things loudly, shamelessly and in public. By the time we come to the ’60s, where this book ends, the history of the fangirl is subtly but inextricably linked to the birth of the women’s liberation movement itself. And it doesn’t end there. In much the same way that they turned their heroes into icons, those silly, screaming, swooning girls were giving birth to pop culture as we know it today.

It’s impossible to write an authentic history of the fangirl without engaging emotionally – I learned that after a few false starts xiii– so this is not an objective history. It’s a map of the human heart in all its messy, beautiful, fascinating weirdness. From daydreaming about saving Lord Byron’s soul to swooning with my friends over pictures of John, Paul, George and Ringo in old copies of Beatles Monthly magazine, I’ve fallen in love with every star in this book, but I’ve fallen in love with their fans even more. These were girls and women who, in big and small ways, broke all the stifling, repressive rules about how they were supposed to think, feel and behave in eras when passionate self-expression often came at a real cost. I hope that as you step into these six very different moments in time with me, you will fall in love with them too.

Bea Martinez-Gatell

Barcelona

December 2024 xiv

NOTES

1 Gaylyn Studlar, ‘Barrymore, the Body, and Bliss’, in Fields of Vision: Essays in Film Studies, Visual Anthropology, and Photography, edited by Leslie Devereaux and Roger Hillman (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), p. 166.

2 ‘The American Girl’s Damning Influence on the Drama’, in Current Literature, 43 (December 1907).

Prologue

The Heroine

In November 1813, two portraits sat next to each other on display at Thomas Phillips’s art studio in Central London. The first, a man, was easily recognisable. With his dark wavy hair, flowing open collar and deathly pale, eerily marble-like complexion, Lord Byron could have stepped straight off the pages of a Gothic romance novel. Fresh from the publication of The Bride of Abydos, his latest ‘heroic poem’, Byron was the literary sensation of the moment. Long before the Hollywood star factory of the 1920s and ’30s perfected the recipe for celebrity, Byron was inventing it for himself.

For the past year, Europe had been in the grips of Byromania. His books were wildly popular, each one selling more copies than the last, but it was gossip about his life that was just as important to his success. Equally thrilling and scandalous, the public devoured every new tale of Byron’s misdemeanours and affairs with the same fervour as they did the romances from his pen. For the first time in history, the brooding, soulful heroes on the page and their handsome, enigmatic creator were intoxicatingly interchangeable.

Byron enjoyed walking the fine line between infamy and celebrity: his poems were filled with mysterious allusions to dark rumours about his own life. But just how autobiographical were they, really? The latest rumour – an incestuous affair between Byron and his xvihalf-sister Augusta – might finally have been a step too far, even for him. In Phillips’s studio however, unphased, he looked serenely out of his portrait and across the room towards the second painting: a young woman dressed in a pageboy uniform, blonde hair cropped short, seductively offering up a tray of fruit to someone just beyond the frame.

Lady Caroline Lamb had not been pleased about the portrait display or everything that the positioning of that particular portrait of her next to Byron’s implied. The previous year, after receiving an advanced copy of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, the book that would make Byron’s name, she had sent him a fan letter. It was uncommon, at the time, for people to write letters like this to authors they’d never met, but there was something about Byron’s writing that drew people in. He wrote with an openness and intensity that made readers feel as if they knew him. His poetry seemed to cry out for participation.

‘I have read your Book & can not refrain from telling you what I think,’ wrote Caroline. ‘I think it is beautiful. You deserve to be and you shall be happy. Do not throw away such talents as you possess in gloom & regrets for the past.’1 She went on to explain that, as a lady, it wouldn’t have been appropriate for her to include her name, but it should be easy enough for him to find out who she was, if he so wished. She asked him to burn the letter – she knew how inappropriate it was to be writing to him like this – but closed with a flirtation: her greatest wish was to one day meet him and to know him.

Over the coming years, Byron would receive hundreds of letters like this one. The anonymous authors, nearly always women, would express being compelled, as if by some supernatural force, to write to him. His poetry, they said, made them feel all kinds of new xviisensations: intense, physical emotions – feelings they couldn’t quite explain but didn’t have a name for either. Often, like Caroline, they wrote to console him. He seemed so melancholic and despairing in his poems. They hoped their letters would, in some way, be of help. Other times, sensing in Byron a kindred spirit, they sent copies of their own poems or wrote to share tragic or sometimes even mundane anecdotes from their own lives.

At first, he’d been perplexed. He couldn’t understand why these strangers were writing to him on such intimate terms. It was so unusual, in fact, that the first time he received a fan letter, he presumed it was from a relative. But as this collection of strange love letters grew, so too did his understanding that a new type of relationship was forming. The power he had over these readers was intense, but the relationship seemed to go two ways. He now belonged to his readers as much as he belonged to himself.

Byron had resolved early on that he would never answer these letters, but there was something about Caroline’s that was different. A poem she’d included was rather good, and he was intrigued by the idea that she might be of noble birth like him. After making enquiries, he discovered that she was the eccentric wife of the Hon. William Lamb, MP and future British Prime Minister. At twenty-six, Caroline was just a few years older than him and known not just for her wit and intelligence but also for her headstrong and passionate nature. Rumour had it she’d been illiterate until her teens, married for love (unusual for the time) and had just come out of a shockingly indiscreet affair with a soldier. The world of the Regency aristocracy was rife with infidelity, but Caroline sounded either nonchalant or actively contemptuous of the unwritten rules of secrecy and silence that safeguarded reputations. Byron had a taste for ‘wild women’. He was now just as intrigued as she was. xviii

Byron and Caroline moved in similar social circles, so it was inevitable that they would meet. When they finally did, they were intensely drawn to each other. They shared an irreverent attitude to life, a mutual curiosity for the world and a deep love of the arts. Caroline, who saw herself as a romantic free spirit, admired Byron’s poetry, as well as his refusal to live by the rules and expectations of society. Byron, in turn, was impressed by Caroline’s intelligence and sharp sense of humour. He was also intrigued by her rebelliousness and emotional intensity. He described her as ‘the cleverest, most agreeable, absurd, amiable, perplexing, dangerous, fascinating little being that lives now or ought to have lived 2,000 years ago’.2 Their relationship began as a true intellectual friendship, but soon neither could deny the intense physical chemistry they shared as well. ‘When you first told me in the carriage to kiss your mouth and I durst not,’ Caroline later wrote to him, ‘and after thinking it such a crime it was more than I could prevent from that moment – you drew me to you like a magnet and I could not indeed have kept away.’3

The melodrama that followed quickly became one of the set-pieces of the Byron myth. It seemed to both confirm the extreme, unholy power of his celebrity and be the perfect metaphor for everything that Regency society feared about his potentially dangerous effect on women and fans.

Through the early summer of 1812, the couple shamelessly appeared together in public. Caroline’s husband was forced to look the other way, but the scandal seriously threatened to put an end to his burgeoning political aspirations. They were so ‘torturously in love’ that they began making plans to elope, but Caroline’s behaviour became increasingly obsessive. ‘She absolutely besieged him,’ recalled the poet Samuel Rogers, a mutual friend. ‘After a great party xixat Devonshire House, to which Caroline had not been invited, I saw her – yes I saw her – talking to Byron, with half her body thrust into the carriage which he had just entered.’4 Other times, knowing how he liked her to dress as a boy, she would disguise herself as a pageboy to visit him unseen. Frequently, these visits were welcomed and planned, but when she arrived unannounced, bitter arguments would be followed by passionate, apologetic reconciliations.

Byron had strong feelings for Caroline, but he was selfish, easily bored and – ironic for a celebrity known for flouting the rules and expectations of society – concerned for both of their reputations. When he finally broke off the relationship after a few short months, Caroline refused to go quietly. She bombarded him with letters pleading with him to press on with the elopement. One letter, signed ‘your wild antelope’, contained a rose gold locket with a lock of her pubic hair inside. ‘I asked you not to send blood,’ she wrote, ‘yet do – because if it means love I like to have it – I cut the hair too close & bled much more than you need – do not you the same … sooner take it from the arm or wrist.’5

No blood was returned. Byron was hiding from Caroline in Scotland at this point, but Caroline – heartbroken, desperate and increasingly distressed – threw herself into winning her lover back at any cost, including any fragments of her reputation that remained intact.

She resurrected her pageboy act to break into his house in Piccadilly. The plan had been to get him alone to talk to him about their future together, but finding him absent, she was overcome with rage. When Byron returned home later that night, he found the words ‘REMEMBER ME’ scrawled in the flyleaf of his copy of the Gothic novel Vathek – a twisted fairy tale of sin, sex, fallen angels, ghosts and a hero’s slow, debaucherous descent into hell due xxto his own insatiable desires and ungodly life choices. The incident would inspire a suitably Gothic response; one of Byron’s bitterest and cruellest Caroline poems:

Remember thee! Remember thee! …

Remorse and shame shall cling to thee

And haunt thee like a feverish dream! …

Thy husband too shall think of thee …

Thou false to him, thou fiend to me!

Still undeterred, Caroline’s rampage continued. The rumour mill was aghast at reports that she had smashed a glass and threatened to stab herself after a tense exchange with Byron at a ball. She didn’t stab herself, but there was a scratch deep enough to draw blood. Or was it that she actually had stabbed herself with a pair of scissors? Accounts were conflicting. Some people said she’d fainted multiple times, others that she’d been carried home by her mother-in-law, dress soaked in blood.

It wasn’t until December that Caroline finally conceded defeat. Just before Christmas, she held a Byron burning ceremony. Caroline led an army of girls, dressed in white, around a bonfire in the village of Welwyn, near her country estate of Brocket. Her servants wore livery with shiny new buttons. She’d had them engraved with the words ‘Ne crede Byron’ (‘Don’t believe Byron’), an inversion of the Byron family motto. As her homemade effigy went up in flames, she threw relics and mementos of their relationship onto the pyre and recited a poem she’d written especially for the occasion:

Burn, fire, burn, while wondering boys exclaim,

And gold and trinkets glitter in the flame. xxi

Ah, look not thus on me, so grave, so sad,

Shake not your heads, nor say the lady’s mad.

Judge not of others, for there is but one

To whom the heart and feelings can be known.

Upon my youthful faults few censures cast,

Look to my future and forgive the past.

Caroline would never be forgiven in the eyes of polite society. By the end of the year, Byron had cemented his reputation as ‘mad, bad and dangerous to know’ (a phrase coined by Caroline herself shortly after meeting him). But Caroline was just mad. Obsessed with her idol and living in a fantasy world, she was the most famous and tragic victim of Byromania. As Byron himself wrote to a friend, her imagination had been ‘heated by novel reading which made her fancy herself as a heroine of romance and led her to all kinds of eccentricities’.6 When she published Glenarvon, a fictionalised account of the affair a few years later, she cemented her fate. For the rest of her life, Caroline would be defined by her Byron obsession – her refusal to let go, her desire to be him as well as be with him and the shameful public spectacle she had made of the whole thing.

Caroline was a complicated person. Recent historians have argued that she most likely suffered from bipolar disorder, but her vilification, regardless of diagnosis, reflected an intense double standard. While Byron’s larger-than-life reputation as a scandalous figure only added to his mystique, the narrative of Caroline’s social downfall reduced her to passivity. She was an erotomaniac. A sex addict. A disturbed victim of lust for a man that had completely escaped from her control. If Byron was the world’s first celebrity, then Caroline was the world’s first celebrity stalker fan. Her literary efforts were dismissed as a kiss and tell or, as Byron put it, a ‘fuck xxiiand publish’.7 Her influence on his work was forgotten. Her depiction as a deranged groupie, even today, in many modern accounts of the affair, casts Byron as the victim of rabid female desire that will stop at nothing to consume him as well as his literary works.

Caroline’s story was unique, but this nightmarish depiction of Byron’s female fans was not. Contemporary reviews were filled with references to the ‘insatiable’ appetites of hysterical readers said to be far more interested in Byron’s body than his body of work.8 ‘The feelings, the earthly desires, the animal passions, are alone and always the object’ of Byron’s appeal, contended one review in the London Magazine.9 And it wasn’t just reviews. Byron’s own writings were rife with allusions to female readers as soul-sucking vampires feeding on his books to satisfy their lust for him. ‘I’ve been more ravished myself than anybody since the Trojan War,’ he once famously wrote.10

As Byron’s ‘most famous fan’, the story of Caroline’s Byromania was more than a melodramatic tale of unrequited love and celebrity obsession or even a tragic story of undiagnosed mental illness. It reflected deep cultural anxieties about the changing role of women in society and a nervousness about women’s relationship with popular culture and visible expressions of female desire that would continue well into the twentieth century. Like Bertha Mason, ‘the madwoman in the attic’, the Byronic Mr Rochester’s first wife in Jane Eyre, Caroline’s crime was not her ‘madness’ – it was her visibility. She was a physical embodiment of the ‘strange, wild and disturbed friendship’ that Byron seemed to have formed, through his writing, with his fans.11 Bertha, after all, is most terrifying because her passion, sexuality and capacity for rage are a part of every woman, including Charlotte Brontë’s pious heroine Jane. Bertha, sent mad by that passion, hidden away from the world by xxiiiher husband, is a warning. A reminder, to Jane, of what happens to nineteenth-century women who allow themselves to be ruled by feeling, emotionality and lust.

There’s a large box in the Murray Archive at the National Library of Scotland. It was once tied with pink ribbons. It is stuffed full of letters from women – from courtesans to schoolgirls – of every walk of life and social class. Many are gushing, adoring and flirtatious; they talk of ‘enthusiastic fire’, ‘melting hearts’ and ‘animated souls’. Many are also bold, self-reflective and self-aware.

Byron, and the majority of his biographers, may have dismissed these ‘foolish’, ‘lovesick girls’ as neurotics, reading the letters as symbols of his power over women, trophies that he hoarded until his death. But in putting pen to paper and expressing their romantic fantasies and often complicated feelings and emotions to a man who was not only a stranger but a lord – far above them in social class – these women were actually doing something quite radical.

In a world that required women to sit down and shut up; a world where Caroline Lamb’s legacy would be as a madwoman and not, as Dickens would later describe her, as ‘a really clever woman – a heroine, in a way’; a world where female desire existed almost completely in relation to needs, rules or expectations of men, in their small way, as we shall see, every fan letter was an insurrection.12

NOTES

1 Caroline Lamb, The Whole Disgraceful Truth: Selected Letters of Lady Caroline Lamb, edited by Paul Douglass (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), p. 77.

2 Leslie Marchand, Byron: A Portrait (London: John Murray, 1971), p. 124.

3 Paul Douglass, Caroline Lamb: A Biography (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), p. 110.

4 Samuel Rogers, Recollections of the Table-Talk of Samuel Rogers (London: Edward Moxon, 1856), p. 231.

5 Douglass, p. 120.

6 Frances Wilson, ‘An Exaggerated Woman: The Melodramas of Lady Caroline Lamb’, in Byromania: Portraits of the Artist in Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Culture, edited by Frances Wilson (London: Macmillan, 1999), p. 196.

7 Alexander Larman, Byron’s Women (London: Head of Zeus, 2016), p. 124.

8 Ghislaine McDayter, Byromania and the Birth of Celebrity Culture (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), p. 47.

9London Magazine, 9 (1824), p. 425.

10 Lord Byron, Byron: Selected Letters and Journals, edited by Leslie Marchand (London: John Murray, 1982), p. 233.

11 John Wilson, Edinburgh Review of Childe Harold Canto IV, in Lord Byron: The Critical Heritage, edited by Andrew Rutherford (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1970), p. 152.

12 Charles Dickens, All the Year Round, 29 (1892), p. 201.

xxiv

Forbidden Fruit, Auguste Toulmouche (1865)

© Glasshouse Images / Alamy Stock Photo

1

Imagination, London, 1812 Bad Romance

The line raced through the girl’s fingers. Her imagination had rushed away. It had sought the pools, the depths, the dark places … And then there was a smash. There was an explosion. There was foam and confusion. The imagination had dashed itself against something hard. The girl was roused from her dream. She was indeed in a state of the most acute and difficult distress. To speak without figure she had thought of something, something about the body, about the passions which it was unfitting for her as a woman to say.

– Virginia Woolf, ‘Professions for Women’ (1931)

I sabella Harvey was seventeen when she first wrote to Lord Byron. She knew it wasn’t a good idea, but she couldn’t stop thinking about him. He was on her mind constantly. In her thoughts, her prayers, her daydreams. It was odd to feel this way about a person she’d never met, she knew that. But at the same time, it felt completely normal – like he was a part of her in some way. Whatever their souls were made of, it was the same thing. What was stranger than her feelings was the violent, irrepressible urge to write.

If she was going to do this, she decided it was best to do it under a pseudonym. She settled on the name ‘Zorina’ after an Italian school 2friend. It had a continental glamour that seemed to fit with the heroines of his poems: Medora, Gulnare, Zorina. He would like that. But more importantly, she would have any replies sent to Mr Weston’s Post Office on Fitzroy Street – no one in her family could know about this. Aristocratic ladies like Caroline Lamb might be established enough to break the rules and damn the consequences, but for middle-class girls like Isabella, virtue and reputation were everything. Byron was not the type of man a young lady should be corresponding with. Especially not a letter like this. ‘Zorina’ was the perfect solution.

There’s something special that happens when a person writes anonymously: it frees them. ‘Man is least himself when he talks in his own person,’ said Oscar Wilde (himself a massive Byron fan). ‘Give a man a mask and he will tell you the truth.’ For women in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, this was even more resonant and potentially explains the Regency obsession with masquerade balls. There were very few places that a girl or woman could experiment with who she was or express herself at all.

According to ladies’ conduct books with stern titles like An Enquiry into the Duties of the Female Sex or Strictures on the Modern System of Female Education (recommended reading for ladies at the time and nearly always written by men), the ideal woman of the ‘long’ eighteenth century was passive and passionless by nature. Her key words to live by were modesty, chastity and restraint. This extended to every part of a woman’s life – from ideally not eating in public to making sure no one ever found out that you were too funny or clever. Even reading too much or reading the ‘wrong things’ in the ‘wrong way’ were thought to be bad for a woman’s health as well as her reputation.

And then there were the rules on chastity. Since passion and desire were seen as unnatural in women, the concept of chastity covered all impure ‘irregular thoughts’ or imaginings that a woman 3might have, as well as anything she might do about them. Female desire was about repression, denial and inhibition of self. This was arduous and isolating, but girls were taught that it was about self-protection. Men were said to be so sexually rapacious and predatory that potential seduction (leading to pregnancy and therefore ruin) was everywhere. Just so much as looking at a man in the wrong way could ‘inflame his desire’, putting a lady at risk.

Corresponding, amorously, with a man you weren’t married or engaged to was something to be approached with extreme caution. As the author of The Complete Art of Writing Love Letters; or, the Lover’s Best Instructor advised women in 1795:

Either the man conceals his basest designs under the cover of the most virtuous and honourable pretences; or the Lady encourages those addresses which she is resolved to disappoint … It behoves our youth to walk with the utmost wariness in this dangerous path, which though strewed with roses and lilies … they too frequently tread on serpents that lurk beneath the beauteous and fragrant flowers.1

HOT-PRESS DARLING

Byron wasn’t the type of guy who even bothered to conceal his ‘basest designs’. At the peak of Byromania in 1812, as his fanmail from women began to pile up, he wrote to his publisher John Murray to complain about the fact that his admirers were anonymous. ‘If I can discover them & they be young as they say they are, I could perhaps convince them of my devotion.’2

On the surface, Byron was exactly the type of rakish seducer that ladies’ conduct books had been warning young women about 4for years. He was said to ‘fall on chambermaids like thunderbolts’, drink his wine out of a cup made from a human skull he’d found in his garden and on his wedding night, he (literally not metaphorically) apparently set fire to his bed while screaming, ‘Good God, I am surely in hell!’3 Wherever he went, he left a trail of broken hearts and fallen women in his wake.

These rumours were true. What was also true – though he would never have liked to admit it – was that Byron knew a lot about isolation, secret hidden desire and victimisation himself. Born in 1788, a year before the French Revolution, George Gordon Byron was the only son of fortune-hunting sea captain ‘Mad’ Jack Byron and Catherine Gordon, an impoverished Scottish heiress (she had not been impoverished when she first married Jack). He was born with a deformity to his right foot, then known as a ‘clubbed foot’, that would cause him shame, insecurity and a limp for the rest of his life. He believed it was a sign that he was cursed by the devil. He was emotionally and physically abused by his mother, sexually abused by his nanny and bullied by nearly everyone at school. When he was fifteen, in an incident that would mark him for the rest of his life, he overheard his cousin Mary Ann, who he was secretly and madly in love with, cruelly deride him: ‘Do you think I could care anything for that lame boy?’4

Resolved not to be defined by his disability, Byron worked hard to become a great athlete. His sport was swimming. By the time he left school, he had grown into a handsome, charming, popular young lord. He liked to read, party and buy clothes. ‘That Boy will be the death of me and drive me mad – I fear he is already ruined. At eighteen!!!’ wrote his mother.5 But beneath the jokes, the reckless spending and perpetual debauchery, something deeper felt wrong.

Throughout his life, Byron would be in love with the idea of being in love but – perhaps due to this childhood of trauma and abuse – never 5fully able to grab hold of it in reality. This was compounded by the fact that he was bisexual, often finding it easier to form closer attachments with men. In England, homosexuality was a criminal offence. Like his female readers, Byron was forced to hide and sublimate a secret, desiring part of himself. And just like Zorina and his other anonymous fans, he often found it easier to write behind a mask.

The first flush of Byromania came in the weeks and months after the publication of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, a fictionalised account of Byron’s travels through Europe during his ‘grand tour’ the previous few years. Freed from the stuffy, repressive confines of Regency society, the trip had been a revelation.

Harold, his literary alter ego, is a young knight with a dark, mysterious past. Tired of his decadent partyboy lifestyle back in England – ‘with pleasure drugge’d, he almost longed for woe’, he says – he decides it’s time for a ‘change of scene’. A precursor to countless spirit-of-the-age travelogues from the restless, tortured brotherhood of self-mythologising man-genius (think Hemingway, Kerouac and Dylan) who set off for foreign lands, or hit the road in the quest for authenticity and freedom, there’s no direction to Harold’s wanderings. His search is for himself.

Like Byron, the poem was a bundle of tantalising contradictions – inspired by the classics but startlingly modern in its politics and sentiment. It felt epic but also, seemingly, deeply personal. As Harold mopes and glowers his way across Europe, his world-weary disillusionment is tempered by a deep and genuine longing for something more. This spoke to a whole generation of readers, struggling themselves from jadedness and ‘Weltschmerz’ (world grief) in 6the fallout from the French Revolution and subsequent Napoleonic Wars. They connected with Harold, felt his pain and saw themselves in his words. But they were also curious about the mysterious, broken-hearted young lord who had written the book. This confessional-style writing was completely new. Was it fact or fiction? Rumour had it, Lord Byron was just as tortured and romantic as his protagonist. Also that he was gorgeous. And single. That old adage ‘a reformed rake makes the best husband’ suddenly felt true again.

In his preface to the poem, Byron had flirted with readers. ‘It has been suggested to me by friends, on whose opinions I set a high value, that in this fictitious character, “Childe Harold”, I may incur the suspicion of having intended some real personage,’ he wrote. ‘This I beg leave, once for all, to disclaim – Harold is the child of imagination.’ Readers were having none of it. There were far too many similarities between Byron and Harold for them to believe that. It would have been impossible, they thought, for anyone to have written so beautifully and so truthfully about love, melancholy and Weltschmerz without having experienced those feelings firsthand. They became convinced that Byron was Harold, and he was only too happy to let them run with it.

Until then, as a charming but eccentric debt-ridden minor lord who believed he was cursed by the devil, Byron had existed on the periphery of the British aristocracy. Now, he was the darling of London. His fame seemed to ‘spring up, like the palace of a fairytale, in one night’, recalled his friend and fellow poet Thomas Moore.6 The whole thing had been ‘electric’. There was so much hype around the book that the first print run of Childe Harold sold out in three days, carriages jostled outside his apartment with invitations to dinners and balls, anyone who knew anyone who knew him (even vaguely) implored them for an introduction and the letters from 7admirers streamed in. ‘This poem is on every table, and he himself courted, visited, flattered, and praised,’ wrote the Duchess of Devonshire. ‘He really is the only topic of almost every conversation – the men jealous of him, the women of each other.’7

It seemed that the whole of London had gone ‘stark mad about Childe Harold and Byron’. But when Caroline Lamb’s 22-year-old cousin, the high-minded Annabella Milbanke, coined the term Byromania, it was the women she took aim at. In her poem, ‘The Byromania’, Annabella depicted Byron as a dangerous cult leader, bringing women under a poisonous spell. That rake reform fantasy that seemed to beckon, so irresistibly, from the stormy depths of that wounded, feeling heart was a trap:

Woman! How truly called a ‘harmless thing!’

So meekly smarting with the venom’d sting

Forgiving saints! – ye bow before the rod,

And kiss the ground on which your censor trod …

Reforming Byron with his magic sway

Compels all hearts to love him and obey

This was the summer of the Caroline–Byron affair, but Caroline was not the only woman Byron was involved with. Nor was she the only woman who seemed to have completely lost her mind at the shrine of Childe Harold.

Lady Falkland, for example, the widow of Byron’s friend Lord Falkland (killed the previous year in a duel), had become convinced that Byron was secretly in love with her. She had apparently discovered this while reading Childe Harold, which she interpreted to be addressed to her. ‘It is not a loveless heart I offer you,’ she wrote to him, ‘but a heart where every throb beats responsive to your own.’88

This type of romantic melodrama was typical of Byron’s fan letters from this period, which were arriving with increasing frequency: ‘You must excuse this madness’, ‘I can resist no longer’, ‘instantly destroy what was intended for your eyes only’, ‘an impulse grateful as irresistible impels me to acknowledge your pen has called forth the most exquisite feelings I have ever experienced’, ‘should curiosity prompt you, and should you not be afraid of gratifying it, by trusting yourself alone in the Green Park at seven o’clock this evening you will see Echo’.9

Annabella was devoutly religious and therefore horrified at the undignified, unwomanly spectacle of Byromania. She reserved her most barbed couplets for Caroline and the other women who increasingly seemed to be attempting to channel their hero themselves:

See Caro smiling, sighing, o’er his face

In hopes to imitate each strange grimace

And mar the silliness which looks so fair

By bringing signs of wilder Passion there

Is human nature to be cast anew,

And modelled on your Idol’s Image true?

Then grant me, Jove, to wear some other shape,

And be an anything – except an Ape!!

These lines would be strangely prophetic. By the time Annabella wrote them, Byron (apparently boyishly playful and good-humoured in private around friends) had fully embraced the theatrical anguish of his Childe Harold persona in public. His fans couldn’t get enough of it, and big feelings (preferably wild, melancholic and/or devoured by passion and remorse) had become the hot new thing.

Within a few years, as his celebrity continued to grow beyond 9anything the world had seen before, Byron and ‘being Byronic’ would become symbols of youthful rebellion and sex appeal as our hero trailed ‘the pageant of his bleeding heart’ across Europe.10 Admirers learned his poetry word for word and were said to ‘practise before the glass in the hope of catching the curl of the upper lip and scowling brow in imitation of their great leader’.11 And if Byron was what women wanted, then Byron was what they were going to get. Young men ‘caught the fashion for deranging their hair, or of leaving their shirt-collar unbuttoned’ – ‘open shirt collars, melancholy features, and a certain dash of remorse were … indispensable’, according to Edmund Reade in 1829.12 But who exactly was imitating who?

Between 1812 and 1816, a period he would later refer to as his ‘reign’, Byron put out a flurry of new works, known collectively as the ‘Turkish Tales’. Today, he’s better known for his more ‘serious’, ‘mature’ works like Manfred and Don Juan, but these romantic swashbucklers would be the making of him. Like a Hollywood franchise that found a winning formula, The Giaour, The Bride of Abydos, The Corsair, Lara and The Siege of Corinth all featured the most crowd-pleasing elements of Childe Harold:

A sexy, brooding anti-heroAn exotic foreign locationIdealised tragic loveScandalous adventuresReportedly drawn from real life.With every new tormented hero – the pirate captain of The Corsair, the vampiric infidel of The Giaour or the incestuous lover of The Bride of Abydos – standing in for the poet himself, readers had unique access to Byron and his world. The heady mixture of scandal and the 10beauty and honesty with which Byron apparently laid his tortured soul bare were irresistible. Although, as the literary historian Andrew Elfenbein has pointed out, Byron’s most scandalous escapades (the dramas that are, today, most closely associated with his legend) actually began after his Childe Harold success. ‘His scandalous aura arose almost as if to justify the qualities of his poetry,’ he says.13

Was it that fame had finally given Byron the freedom to admit and indulge his darkest, most immoral impulses? Or was he just method acting – giving his adoring audience the infamous Lord Byron of their nightmarish daydreams? Either way, there was (and still is) something incredibly sexy about an outlaw. Byron had known this for a long time. His literary ancestors were the great anti-heroes of the past, most notably Milton’s smouldering fallen archangel, Satan, from Paradise Lost. Cast down from heaven for daring to challenge the tyranny of God, Satan was – until Byron – the ultimate poster-boy for the tormented pursuit of moral individualism.

What Byron added to the mix (in addition to his beautiful, terrible, most confounding self) was romance. This was the hero-villain as lover. The great-grandfather of a long line of moody, brooding sex symbols from Mr Darcy through Heathcliff to Edward Cullen and Christian Grey, Byron taught the world that ‘girlish innocence can triumph over manly experience through the redemptive power of love’.14 Both hero and victim, the Byronic Hero’s cynical, remote exterior is really just an act of self-protection – a product of the ravages of the world that have forced him to harden his heart. What lies beneath is the most feeling and sensitive man. As Byron himself wrote in The Corsair:

His heart was form’d for softness, warp’t to wrong

Betrayed too early, beguiled too long.

11These lines were the most quoted across all of Byron’s fan letters. And it is an achingly compelling fantasy. Lone, wild and strange the Byronic Hero may be, his darkness and misanthropy only serve to intensify his connection with his beloved – the one woman in the world with the power to see the real him. It makes her goodness and her love even more radiant. She is the purest good. The only truth. The one thing in the world that can give meaning to his otherwise hellish existence.

There’s no God in Byron’s world. She is his only possibility for redemption, which is strangely empowering – in a way. Imagine being the one person in the world with the power to calm that storm. ‘Without one hope on earth beyond thy love / And scarce a glimpse of mercy from above,’ he writes:

Yes – it was love – if thoughts of tenderness

Tried by temptation, strengthened by distress

Unmoved by absence, firm in every clime

And yet – oh more than all! – untired by time;

Which nor defeated hope, nor baffled wile,

Could render sullen were she to smile

The infinite depths of his torment are really just a promise of his profound capacity to love the right woman passionately.

It’s no surprise that Byron’s earliest fans, women who felt they had gotten to know the ‘real Lord Byron’ through his writing, were attempting to save him. This was the model of love he had given them, and he seemed to be desperately in need of it.

‘You are unhappy – a being feared and mistrusted,’ wrote one anonymous admirer. ‘The interest I feel – the eager wish for power to contribute (tho’ but a mite) to your happiness arises from sympathy adding strength to compassion.’ She included a copy of the 12Bible with her letter, urging him to embrace Christianity as an antidote to his pain. Another woman, similarly anonymous, explained that it was his writing itself that had proved his goodness to her: ‘I am told my Lord Byron is an infidel but no, it cannot be, I have fought your cause and said, he who can so feelingly describe the purest of sentiments, must acknowledge a God of love.’15

Even Annabella Milbanke – the woman who had initially mocked the idea of ‘reforming Byron’ – came over to the dark side in the end. After finally meeting him at a party, she caught the Byromania herself. She remembered the exact moment her feelings changed. They’d been standing together in the middle of the room:

I felt that he was the most attractive person; but I was not bound to him by any strong feelings of sympathy till he uttered these words, not to me but to my hearing – ‘I have not a friend in the world!’ … I vowed in secret to be a devoted friend to this lone being.16

Annabella became convinced that she was the one woman in the world who actually could save that beautiful, tortured soul. And for a brief enchanted moment – fuelled in part by the fact that Byron had mounting debts and Annabella was a wealthy heiress and in part by his need to distract the public from escalating rumours that he was sleeping with his sister – he wondered if it might actually be true.

‘I am thankful that the wildness of my imagination has not prevented me from recovering the path of peace,’ he wrote to her. ‘My plans – my hopes – my affection into love – I could almost say – devotion to you – forgive my weaknesses – love what you can of me … and I will be – I am whatever you please to make me.’17 Reader, she married him. 13

I know it may be painful to imagine now, but rake reform (aka taming fuckboys) was advertised as a manifestation of girl power in the eighteenth century.

Young women, like Annabella and Byron’s anonymous saviours, were raised to believe that female power lay in virtuous domesticity. If a man like Byron could be reformed and therefore ‘tamed’, through marriage to a good woman, into renouncing his rakish vices and philandering ways, that was a win for the fairer sex – an expression of female power and a vindication of domestic life. The sharing of feelings, especially of sympathy as mentioned by many of Byron’s anonymous reformers, were thought to be an important part of the ‘conversion process’.

The belief that rakes could be reformed, and that it was the mission of virtuous women to help them, was propagated by sentimental novels like Samuel Richardson’s Pamela: England’s first bestseller and the first novel to spark a wave of popular enthusiasm that we would recognise as fandom today. It’s the story of a fifteen-year-old servant girl, Pamela, who finds herself in a morally questionable situation when her new employer, the rakish Mr B, begins making unwanted sexual advances. Through the novel, which is told as a series of letters, Mr B’s attempts at seduction become increasingly dark, manipulative and scheming, but Pamela remains steadfast in her virtue. By the end of the novel, Mr B has been converted to goodness.

In the novel’s pivotal scene, Mr B reads the letters that Pamela had been writing to her friends and family, which describe her experience of his abuse. Seeing the world through her eyes is the turning point in his path to redemption. Pamela and her virtue make him want to be a better man. They fall in love, get married and are finally able to consummate their love with Pamela’s saintly virtue still intact. This good girl/bad boy redemption story would 14become a staple plotline in novels of the second half of the eighteenth century and – from Bridgerton to Beauty and the Beast – is still with us today.

Feminist literary critics like Tania Modleski who have studied the enduring popularity of these stories have theorised that part of women’s enjoyment of good girl/bad boy narratives, which most often culminate in marriage, is the power struggle. When the bad boy gets down on one knee to propose, he literally is on his knees: the woman has dominated him. Modleski calls this a ‘revenge fantasy’, but the revenge is over the patriarchy more than the bad boy himself.18 In forcing him to connect with his feelings, it’s a victory of emotion – something that both eighteenth-century men and women were, on the whole for different reasons, required to repress.

Byron was a perfect candidate for reform because his inner softness and ability to feel were already so visible in his poems. It wasn’t just that he needed to be saved; he wanted to be saved! His fanmail is filled with heartfelt confessions of female feeling and often suffering too. ‘I have known what it is to have my youth blighted by unkindness, to be feared, hated, neglected,’ said the lady who sent him the Bible. Another, who called herself ‘Rosalie’, was bolder: ‘Has he a mind that possesses the power of friendship? And that feels the ingratitude, and malice of an unfeeling, prejudiced and misjudging world? … Does he seek a virtuous, innocent and faithful friend?’ She explained that she couldn’t share her identity, but he could reply by posting a message in the Sunday Observer ‘bearing the name Antonio’.19

This was more than sympathy or even romance. Byron’s confessional writing – in all its messy, tortured, feeling humanness – connected with people in a way that poetry never had before. As yet another woman who said she ‘could not affix her name’ explained: 15

I must be allowed to observe that your Lordship is not addressed by one of those frivolous beings, who conclude that it is very sentimental and captivating to sigh away an hour over Lord Byron’s poetry, merely because it is what is deemed the fashionable reading of the day, but it is one, whose deeply wounded spirit was occasioned in early youth, for several years past to shun all society as an intolerable annoyance.

His fans were writing to him because they identified with the feelings and emotions he described – and because his impassioned, confessional writing had given them a model and language that they could use to express these thoughts and feelings in themselves. That so much of his fanmail came in the form of poetry is testament to this fact. As modern readers, we might look at these letters and see only cringeworthy torrents of hyperbole and melodrama, but in 1812, that was the point. In sitting down to write to Lord Byron, these women had found a safe place to feel and express – to experiment with being Byronic themselves.

For many women, this emotional connection was born out of the magic of reading itself. They often described reading Byron in almost supernatural, mystically eroticised terms, as if, through the alchemy of his words, Byron had become a physical presence in their lives. ‘Often have I wandered in these gardens with your poem for my companion & with thee conversing have forgot all time,’ wrote Anna from Kensington Palace. ‘I have hung in rapt attention over every line of Childe Harold. I am not a critic but an inexperienced young woman, but the language of genius & of nature must be felt.’20

Sometimes they struggled to make sense of these feelings, even when writing to Byron himself: ‘This empire you obtained over me by means of your writing,’ wrote Zorina. ‘How intimately I 16connected with the author and his works. This was natural, but how happens that the author is now more to me than his writings, that he is the food of my thoughts, the impulse of my life … the bright dream of my existence.’21 The infamous courtesan Harriette Wilson was less confused. She wrote to tell Byron that she’d taken her copy of Don Juan to bed with her and that it had kept her up all night.

Byron was notoriously ambivalent about his female readers. In public, he scoffed at the idea of catering to female tastes: ‘I have not written for their pleasure; if they find theirs in the perusal of my works, it is because they wish it … I have no intention of writing books for women.’22 But in private, particularly in the early days, he understood the importance of the women’s market, monitored which books sold best with women and enjoyed his status as a Romantic heart-throb. ‘Who does not write to please women?’ he asked his friend Thomas Medwin, admitting that he was most pleased with the success of The Corsair than any other book ‘because it did shine, and in boudoirs’.23

By the time his year-long marriage to Annabella fell apart in a storm of revelations so shocking (and potentially criminal) that he was forced to leave England never to return, Byron wasn’t just a celebrity. He was an otherworldly multimedia event. A fictional character in real life. Holed up in Villa Diodati, a beautiful mansion on the shores of Lake Geneva, brooding on past regrets and unspeakable sins, the incarnation was complete. ‘He had Childe Harolded himself,’ wrote his friend Sir Walter Scott, ‘outlawed himself into too great a resemblance with the pictures of his imagination.’24 But let’s not forget that it was his fans’ fantasies, as much as his own, that had given birth to all this.

Byromania was born in a whirlwind of curiosity about one, very real, man. But, as we know too well these days, the power of celebrities is not who they are. It’s what they mean. For Byron’s female 17fans, this was often deeper and more complex than the ‘reforming Byron’ fantasy of Annabella’s poem. Byron and his celebrity had created new ways for people to enjoy and engage with books. And as his fan letters were beginning to prove – consciously or not – he was inviting women to become active participants in the story. His idealised soulmate may have been virtuous, pure and true, but she was also a lot like him. In his narcissistic fantasies of love as connection with a perfect other self, Byron (one of the most misogynist writers of the Romantic era) was inadvertently creating a radical vision of equality:

She was like me in lineaments – her eyes

Her hair, her features, all, to the very tone

Even of her voice, they said were like mine …

She had the same lone thoughts and wanderings

The quest of hidden knowledge, and a mind

To comprehend the universe.25

BAD READERS

By the time he went into exile in 1816, the word ‘Byron’ was hot property. It wasn’t just his books that were big business. Anything associated with Byron that could be marketed and sold was marketed and sold, and even things that couldn’t be marketed or sold gained special currency if they were even slightly connected with him.