Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Ian Fleming Publications

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

From the shores of Dieppe in 1942 to The Foreign Department in Kemsley House, from treasure hunting in Norfolk and fine dining in London to a golden typewriter in Jamaica, these are the writings of Ian Fleming. This collection of rarely-seen journalism spans Fleming's career as an author, encompassing reviews for the Sunday Times, Second World War documents, travel journalism and his correspondence with Raymond Chandler and Geoffrey Boothroyd. It also includes newly-unearthed articles that have not been available for over half a century plus two very early works of fiction.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 568

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iii

TALK OF THE DEVIL

IAN FLEMING

Contents

Introduction

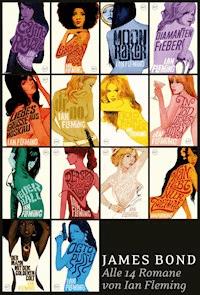

Ian Fleming is a unique literary figure, inasmuch as he is known for a single creation that has by now escaped any of the normal orbits of writer-to-subject relations. Of course, all authors’ reputations eventually become condensed into a phrase or even an adjective – we call something “Dickensian” or reference a “Graham Greene hero” – so the formula “Ian Fleming’s James Bond” or even just “Ian Fleming’s 007” is in its way an unsurprising epitaph. His name and reputation shine brightest these days in the title sequences of movies that have sometimes a close (CasinoRoyale) and sometimes a very remote (all the other recent Bond films) connection to his writing.

It’s an odd fate for an avid and ambitious author – one perhaps shared only by Arthur Conan Doyle, another good writer whose destiny was to be singly sublimated into his own invention. (Singly, at least, if one overlooks the truth that the Jurassic Park series is essentially derived from Conan Doyle’s Challenger series, and his TheLostWorld.) And so, the pleasure of this collection of miscellaneous prose that Fleming produced as a working journalist – chiefly over his prime creative years, the nineteen fifties – is to be reminded again of what a fine, evocative, sentence-by-sentence writer he was. Along with Conan Doyle and his close friend Raymond Chandler, Fleming is the best instance of the writer who, without literary pretension of any kind, wrote so well that his adventure stories, whatever their distorting thinness might be as mirrors of reality, keep their claim on our imaginations even when they lose their claim upon our surprise. He talked of himself as a writer of ‘suspense’, but his books still shine long after whatever suspense they contained is overwhelmed by time and familiarity. We know exactly how the stories will turn out and re-read them anyway. (In truth, we knew exactly how the stories would turn out when they were written – Bond is no anti-hero, he’ll alwaysprevail – and still we re-read them.)

For Fleming was, one realises turning these pages, above all an observational viiiwriter, one who could condense sights and sounds and tastes into a handful of memorable descriptive sentences. It is the atmosphericsof his Bond books that give credibility to their adventures, and his non-fiction, collected here, is pretty much a continuous distillation onto the page of those atmospheres, from London to Turkey to Jamaica and beyond. He makes moods not from self-consciously ‘poetic’ evocation but from an inventory of essential elements – from objects, things seen and sensed. He does it so well that every writer, in any genre, can still study his sentences and learn from them.

Fleming’s life, now recounted several times in successive biographies, was one of significant adventure in the Second World War, and a vivid life as a journalist, chiefly for the SundayTimesof London afterwards. Whatever work the winds and weather of the world did on his character, he was born into a daunting family; there’s a surprising glimpse of him in the art historian Kenneth Clark’s autobiography, who, talking about Fleming’s pretty mother who lived near a Clark family retreat in a remote part of Scotland, admits that he was scared away by “her formidably well-equipped sons, who terrified me then as much as they did when I encountered them in later life.”

It is always pleasing to have a pet theory about a writer confirmed by the writer, and not the least of the pleasures of this collection is that Fleming confirms a pet theory of my own. That is, that the writing and example of Peter Fleming, Ian’s older brother, was, so to speak, the missing planet X that explains the deviations and odd orbit of Ian’s own. Peter Fleming, as too few readers perhaps now know, was the author of several superior travel books in the nineteen thirties – BrazilianAdventureand TravelsinTartaryare the most famous – memorable for their almost Wodehousian humour and their deliberate note of self-deprecating irony. (Afterwards, he went on to write the “Fourth Leader” for TheTimes, the light-hearted ‘extra’ editorial that distinguished the paper then. Out of solidarity in anonymity – I used to do the same for TheNewYorkerin what was called “light Comment” – I for a long time collected “Fourth Leader” anthologies from the Peter Fleming era when one could find them in London bookstores. They rewarded the reader with high-hearted and charming sentences.)

This reader long imagined that the older brother’s adventures – and his tone of light-hearted and unboastful derring-do – must have affected the younger brother’s imagination of what a hero was, and indeed here is Ian, writing that, ix“In this era of the anti-hero, when anyone on a pedestal is assaulted (how has Nelson survived?), unfashionably and obstinately I have my heroes. Being a second son, I dare say this all started from hero-worshipping my elder brother Peter.” Photographs of the young Peter, for what it’s worth, look exactlylike Ian’s description of James Bond – with his otherwise puzzling and oft-insisted-on resemblance to the American songwriter and sometime character actor Hoagy Carmichael – more so than photographs of the younger Ian.

What is significantly different between brothers is the tone. Peter’s is self-consciously ironic and self-deprecating, in the manner of the Waugh and Wodehouse twenties; Ian’s is from early on, taut and essentially earnest, in the thirties and forties manner of Greene and Orwell. In all of these pieces he takes his subjects lightly, but he takes them seriously. The development of Interpol, the art of Raymond Chandler, even the Seven Deadly Sins – for all that he treats these subjects with dapper elegance, and sometimes dapper disdain, they seem to matterto him, and he wants to make them matter to the reader. Where Peter, for all that he had a ‘good war’ in the forties, was still very much a child of the Noël Coward moment, Ian seems to have been made by the War in ways that gave him a tougher inner iron than his brother. His memoir here of the raid on Dieppe, a legendary foul-up that may – or more likely, may not – have taught essential things for the later amphibian invasion of the coast of France, is tight-lipped and taciturn, pained in a manner that suggests a more searing experience than its unemotional tone allows – or, rather, one that its unemotional tone implicitly enforces.

Ian is modern. Though one had a sense from the Bond books that Fleming had many attitudes about foreign peoples typical, unsurprisingly, of a man of his time rather than ours, it is still cheering and unexpected to see how resolutely cosmopolitan he was. He was a fan of the nascent Commonwealth and, here, as in his ThrillingCities, published in his lifetime, he urged his British readers to “Go East, young man” – emigrating or at least living for a time in an emerging new world he saw as more healthily energetic than a sometimes-exhausted Europe. In his list of political desires, he makes paramount the “enthusiastic encouragement of emigration, but more particularly of a constant flow of peoples within the Commonwealth.”He had the inevitable prejudices of a British man of the end of the Imperial era, but any charge of significant racism is one that these pages seem to acquit him of.x

But above all we read his non-fiction for echoes of his fiction, and for clues as to its hardy excellence. Ian is very much a writer of the post-war boom that, for all the rationing and the stringency of the currency export conditions, still allowed ‘luxury’ goods and practices into Europe sufficiently to inform his prose. He always seems to be having a good time. Fleming is known, quite wrongly, as a ‘placement’ writer, someone who used proper nouns of products to give credibility to his work. But this is misleading. As he explains himself, deftly, it was his concentration on all of the specific objects of sight and sound and smell, that, for him, as for any real writer, gave his work its density and its credibility; the ‘product placement’ was purely accidental. He writes tellingly that:

“… the real names of things come in useful. A Ronson lighter, a 41 ⁄2 litre Bentley with an Amherst-Villiers super-charger (please note the solid exactitude), the Ritz Hotel in London, the 21 Club in New York, the exact names of flora and fauna, even James Bond’s sea island cotton shirts with short sleeves. All these small details are ‘points de repère’ to comfort and reassure the reader on his journey into fantastic adventure. I am interested in things and in their exact description. The technique crept into my first book, CasinoRoyale. I realised that the plot was fantastic, and I wondered how I could anchor it to the ground so that it wouldn’t take off completely. I did so by piling on the verisimilitude of the background and of the incidental situations, and the combination seemed to work.”

These straightforward words are not the words of a hack, à la Judith Krantz, trying to stuff the pages with chichi references; they are the words of a working writer, determined to lend credibility to fantasy – inventorying the things of this world in order to make credible a plausible alternative one that sits within it. Conan Doyle did the same, in his Victorian world, with his elaborately detailed train schedules and descriptions of bric-a-brac stuffed interiors and his general assertion of the thingnessof Holmes and Watson’s world. Each object credibly registered opens a path for fantasy to enter into.

Elsewhere in these pages, Fleming states with admirable succinctness that “I am excited by the poetry of things and places,” adding that “it is surely more stimulating to the reader’s senses if, instead of writing ‘He made a hurried meal of the Plat du Jour – excellent cottage pie and vegetables, followed by home-made trifle’ you write ‘Being instinctively mistrustful of all Plats du xiJour, he ordered four fried eggs cooked on both sides, hot buttered toast and a large cup of black coffee.’ … four fried eggs has the sound of a real man’s meal, and, in our imagination, a large cup of black coffee sits well on our taste buds after the rich, buttery sound of the fried eggs and the hot buttered toast.” He concludes the self-analysis with another memorable aphorism: “What I endeavour to aim at is a certain disciplined exoticism.”

A disciplined exoticism! This is surely what every writer of thrillers of Fleming’s kind aims at, and too rarely achieves – and not just writers of thrillers. When we take pleasure again in re-reading OnHerMajesty’sSecretServiceor Thunderballit is less for the fantasy or ‘action’ sequences, well-rendered though they are, but for the way that Fleming’s knowledge of ‘things and places’ gives his work, exactly as he wanted, its peculiar poetry. Fleming crisply offering all that he knows about the place and social history of the Boulevard Haussmann in Paris is what makes that locale work, however improbably, as the headquarters of SPECTRE, complete with secret meeting room and Blofeld’s electric-executioner’s chair.

W.H. Auden once wrote of the centrality of the ‘mythopoeic’ imagination to literature, meaning the ability of words to conjure up people or places, à la Tolkien, that seem to exist independent of their creators and of the tales their creators tell. He offers Sherlock Holmes as a prime instance – we can always imagine more mysteries for Holmes to solve and we do – and Bond surely takes his place alongside him. But the secret of the mythopoeic imagination, this book reminds us, is not imaginative extravagance but atmospheric specificity: we know Holmes by his fogs, and Bond by his island. Or rather, by the dramatic contrast of white and grey, placid, peaceful London, with its Chelsea squares, with the green and yellow tropics – exactly what he meant, perhaps, by ‘disciplined exoticism.’ Of all the places that Fleming evokes in these pages, none is evoked with such pleasure and specificity as his beloved Jamaica. Though one senses a certain disappointment on the author’s part at being in such bondage as to never become quite as significant a literary artist as he thought he might be – his efforts at a more ‘literary” Bond book, in the original TheSpyWhoLovedMeand Quantumof Solacenever quite worked – that the Bond books allowed him to work and write on his island seems some recompense. His evocation of the island is quite as stirring, in its lulling way, as Hemingway’s of Cuba: “Coral rocks and cliffs alternate ‘South xiiSea island’ coves and bays and beaches. The sand varies too, from pure white to golden to brown to grey.The sea is blue and green and rarely calm and still. A coral reef runs round the island with very deep water beyond and over the reef hang frigate birds, white or black, with beautifully forked tails, and dark blue kingfishers. Clumsy pelicans and white or slate grey egrets fish at the river mouths.” Lovely and loving sentences! That they formed the background for the most resonant of modern adventure stories is, one feels reading them, almost a lucky by-product of watching a writer at a writer’s real work, which is, simply, watching.

Adam Gopnik

October 2024

TWO STORIES

A Poor Man Escapes

This is one of the earliest known stories by Ian Fleming. It is thought that he wrote it in 1927 at the age of nineteen while under the tutelage of Ernan Forbes-Dennis and Phyllis Bottome in Kitzbühel, Austria. The manuscript resides in the Michael L. VanBlaricum Collection of Ian Fleming and Bondiana in The Rare Book and Manuscript Library at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

It was Christmas day. Snow paved the streets of Vienna and tiled the roofs of the houses with white. It wasn’t a kind Christmas day, for every now and then a sharp wind reached down into the slim streets and whipped the surface snow into a blizzard. There was little traffic and few people abroad. Those who were out of doors hurried along with pinched blue and red faces clutching their fur collars up round their ears and sometimes breaking into sharp little runs as the wind snapped round their legs. Heavy flakes of snow were falling sparsely, muffling the air and the ground so that there was little to be heard but the tread and scuffle of hurrying feet, and the occasional ssh-flop as a heap of snow slid off a tall roof on to the pavement.

In the Himmel Strasse, a small cul-de-sac blocked by a thin crouching church, even these soft noises were absent. Heaven Street was undoubtedly an optimistic name for such a disreputable and retiring little lane. Even the snow, clinging to the roofs of the stooping little houses and the 50 yards of cobbled way, could only accentuate the disgraces and poverties of this little street. Even the church, the only excuse for such a glowing title, had half crumbled into ruin as if ashamed of the part it had played in causing such an error. The people who overcrowded the half-a-dozen little houses were in most cases as disreputable as their quarters. Thieves, tinkers, hawkers, street cleaners and the like, with their wives 4and families, made this street their stronghold and formed a small but self-sufficient community.

Amongst the leading lights of this community was a certain Henrik Akst. Some said he was a Pole, others a Norwegian (what was he then?), but he had lived in Vienna 30 out of the 40 years of his life and was generally accepted as a Viennese. He was a news vendor; but on Christmas Day he had no papers to sell and instead he sat watching his wife die. The process was brief, but painful, and when he rose to cover the now tranquil face his own eyes, besides tears, held a wild drawn expression of pain, while his features already thin with hunger assumed a new gauntness.

Leaving the bed, he crossed in two strides to the window which he opened to the drifting snow flakes, and at once the small heat of the room was drained out into the street mercifully taking with it the heavy smell of disinfectants which hung round the bed.

Henrik tidied up the room methodically for the first time in his life. All his meagre belongings he stuffed into his pockets. A razor, a knife, two spoons, a fork, a photograph of his wife in a gilt frame, and other objects as worthless. He made a parcel of some plates and cups, and with this in one hand and an old pair of boots in the other he left the room shutting the door carefully, but without another look for the still figure on the bed. But in a minute he was back to take, with still averted eyes, the bottle of disinfectant from beside the bed, then the door closed finally.

Out in the street, however, he did so far forget himself as to look up at their window, as he always did when he went out, to see his wife waving and smiling at him, but he at once looked away again, and soon he had left the narrow cul-de-sac for the trampled whiteness of a larger street.

The pawnbrokers was open even on Christmas day. He attempted to be genial but with reserve for little of value but stolen goods could come from such a man as the news vendor.

‘Selling presents already, eh, my man?’ he said, rubbing his hands and eyeing with disfavour the poverty and dejection of his customer.

But Henrik merely greeted him with the customary ‘God bless you’, and piled his treasures on the wooden board which served for a counter.

At first the pawnbroker was indignant. ‘When I’m a rag and bone man, then you can bring that sort of stuff to my shop,’ he said, but soon, for he was 5a kind-hearted man in his way and it was Christmas, he offered two Austrian shillings for the lot. Henrik accepted at once and after blessing the pawnbroker and leaving the shop, he set out towards the distant spires of the cathedral in Stephansplatz and the centre of the town. He hadn’t gone far before he felt the thud of something against his hip as he walked. He remembered at once, of course, the medicine. What a pity, he might have got an extra few groschen for the bottle – well, well, it would do for another time! But then he suddenly remembered – but there would be no other time, at least not for about six months, that would be about what he would get. He was about to throw it away – it was a dark red colour – what a lovely pink smudge it would make if he threw it hard into the snow and it broke. No, perhaps it might be some good – he stuffed it back into his pocket. A gust of wind licked round his legs and he broke into a weak, stumbling run, clutching his meagre coat about him with one hand and the two shillings in the other. Curse that bottle. It bumped against him as he ran, and it seemed to weigh a lot, but perhaps that was only because he was so weak, he had eaten nothing for two days. All his small earnings had gone to feed his dying wife. But now, the wind had flicked a little warmth into his body, he clutched the 2 shillings tighter and ran faster.

The Café Budapest was full. The breath of the people and the heat of the stoves and of the kitchen had turned to moisture on the window so that the lights shone out into the street like haloed golden stars. An old couple by one of the tall plate glass windows had rubbed away a little square of moisture, so that they could see the figures outside, and so that the less fortunate people outside could see and envy, and perhaps recognise them, and say afterwards to their friends, ‘Do you know who we saw at the Budapest today, why it was the Kirnskys’, and everybody would be envious and say, ‘but I thought they were so poor, and they’re so old now and never go out anywhere.’ Frau Kirnsky grinned to herself, old people didn’t die as easily as that and besides it was Christmas. She looked affectionately at the old man, who sat mumbling over a cup of coffee, nodding his disjointed old head in time to the music. Hullo, who was this, a musty black shape moved across the window, and bent down to the space which she had cleared. Good heavens, they couldn’t allow that sort of a person into the Budapest. There, thank heavens he had gone. But next moment the inner door had opened quietly and Henrik was peering through a slit in the heavy curtain which covered the double doors and kept away the cold. All 6the waiters seemed engrossed. He noticed an empty table over in a corner, and in a moment he had slipped in and across among the tables to the corner, had hidden his lower half under the tables and was industriously reading a paper held close across his chest. The waiter came up and saw only a pale gaunt little face with a mop of unkempt hair peering at him over the paper. Nothing very extraordinary about this. ‘Coffee and double Vermouth,’ said Henrik. The waiter moved away and the few people who had noticed his entrance with surprise decided he must be all right if the waiter accepted him. Only the Kirnskys had risen and were moving puzzlingly towards the door, looking with disgust at Henrik. But Henrik noticed nothing, but that he had arrived.

He beckoned to a man passing with a tray of cakes and selected three of the richest paying for them with his 2 shillings. ‘Keep the change,’ he said magnificently and his position was fairly established. Soon his coffee and vermouth arrived and he was stuffing and drinking away as hard as he could, still holding up the paper as if he was tremendously interested in something he had found in it. In reality he sensed nothing but a blank whiteness in front of him and a wonderful feeling of warmth and triumph. The heat of the room was thawing his body, which was tingling all over, and inside was a little nucleus of fire which was the vermouth, but above all his heart was warm with triumph and a splendid feeling of not caring what happened afterwards. He nodded and the paper dropped a few inches exposing a ragged scarf which concealed the fact that he had no shirt; but he was instantly awake again and pretending to read as hard as ever. But soon again his head was falling forward, the music came to him in waves, which alternated with waves of noise and talk and clatter of cups and spoons, like the rattle of the shingle when a wave has fallen and is sucked back down the shore like a boomerang to be thrown again and again.

Everything was rose coloured and gold. He was floating through an infinite sunset, across green hills towards a distant range of mountains. If only he could get there. He strove to reach them, when suddenly the sunset collapsed beneath him and he fell – thump – thump – thump. He gradually woke up. The waiter was shaking him and hitting him on the back to wake him. Luckily it was the cake waiter to whom he had given the tip.

‘You know you shouldn’t be here at all – and at any rate if you want to sleep go to a hotel – mind don’t do it again or the manager will see and turn you out.’ He moved away.

7People were staring. Henrik was dazed and still half asleep, but he raised the paper again and held it close before his face. He nodded but pulled himself together – ‘Now then Henrik – you don’t want to be arrested yet do you – quite time enough when the bill comes and you haven’t got any money to pay it with – Quite time, quite, quite – .’ The paper fell to the floor and Henrik’s chin sank on to his chest. Again he saw the distant line of ragged peaks – black against the last range of the sunset – again came the sudden desire to reach the black distant goal, and again as he seemed certain to reach it the dream gave way around him, and this time it was the manager who was knocking him on the shoulder.

‘Here, clear out of this’, said a voice from the distance, and the shaking became rougher. Henrik got up displaying all his rags to the scandalised manager and the disgusted onlookers, who had been longing for something to happen to the sleeper.

‘But I’ve paid for my food,’ said Henrik grasping at his brief luxury as he saw it escaping before him.

The manager didn’t heed him. ‘Wait there,’ he said, and pushed Henrik back into his seat. He didn’t want the indignity of having to lead Henrik out himself with the possibility of a vulgar brawl.

A tear crept from the corner of each of Henrik’s eyes and crept down his cheeks. How lovely it had all been while it had lasted. He sank his head on his hands in despair, the sound of the manager calling to the policeman at the corner reached him – what could he do to keep this wonderful world of light and wealth. As if to mock him the music began again, a Viennese waltz drifted through the warm air into the coldness of his despair.

Suddenly he noticed that he was uncomfortable – he was half sitting on something hard which was sticking into him – Of course the medicine bottle. He took it out and looked at it – furtively under the table – and suddenly he noticed the label

Poison

For external use only

or according to the doctor’s instructions

and the word ‘Lysol’ printed in red on a large slip of paper across it. Why, of course. He could have cried out in his happiness – here was his world given 8back to him – no more of the cold and the snow – no more poverty and squalor – instead the lovely dream, and what was it – oh yes, those mountains perhaps he might reach them one day too.

A vague moment of hesitation came to him, but he heard the policeman scraping the snow off his boots on the wire mat outside and stamping. Quickly he raised his newspaper and under cover of it the precious bottle. A terrible spasm clutched at his body – the bottle fell from his fingers and smashed on the floor – His whole frame stiffened and then relaxed – shuddering. His head fell forward on to his breast.

‘There he is,’ said the manager, entering with a burly policeman – ‘There he is, asleep again – he has no money – arrest him – he can’t pay his bill.’

But Henrik had paid and was rich for the first time in his life.

The Shameful Dream

Ian Fleming was advised that the character of Lord Ower in this story, written in about 1951, resembled too closely his employer, Lord Kemsley, and it was never published. It appears to be unfinished though it is not certain that this is the case.

The fat leather cushions hissed their resentment at the contact with the shiny seat of his trousers and hissed again as he leant back while the chauffeur tucked mutation mink round his knees. The door of the Rolls closed with a rich double click and with a sigh from the engine and a well-mannered efflatus from the bulb horn the car nosed with battleship grace away from the station approaches.

Caffery Bone, literary editor of OurWorld, eased himself forward and reached for the cigarette case in his hip pocket and took out a cigarette – ‘selected with care an ivory tube’ he reflected and for a moment pulled down Elinor Glyn, Ouida and Amanda Ros from the boxroom and sniffed at their dust. Where were the euphemisms of today? Perhaps only in America: ‘Comfort Station’, ‘Powder Room’, but then we talked of Public Conveniences and ‘Loos’. Perhaps they had just been stripped from all languages down to the lingering taboo words, down to sex and lavatory. Yes, there they were: petting, charlies, go somewhere, pansies, a veritable mine of them. ‘The Last Shy Words’ would make a good title. But not for OurWorld. Good God no. He could hear the telephone ringing already: ‘Mr Bone?’ Yes. ‘Linklater speaking. The Chief says would you slip up a moment.’ He could feel the soft pile carpet and see the drooping walrus moustache saying ‘Sit down Mr Bone.’ Then the shiny leather of the single chair, known throughout the building as ‘The Hot Squat’, then the redoubtable ‘Icy Pause’, then ‘Mr Bone, my attention has been drawn …’

10Bone found that his body had tensed and that the ash had grown long on his cigarette as he stared wide-eyed at the television screen which was the chauffeur’s back. He fiddled with the gadgets in the fat leather arm of his seat in search of an ash tray. Silently the glass driver’s partition slid down and a voice issuing from the walnut panelling near his right ear said, ‘Yes Sir?’ Bone started and the ash fell on to the mink rug. ‘Oh, er, nothing,’ he said. He fiddled some more and the partition quietly closed, but in a moment there came a soft crackling of static and the Nutcracker Suite sounded down from the ceiling. Bloody box of tricks thought Bone as he ground out his cigarette on the sole of his shoe and pushed the stub down between the leather cushions. Different kettle of fish to the modest Sheerline saloon which carried Lord Ower to and from his offices in Fleet Street. Must be Lady Ower’s car. Everyone said that she was the one who spent the money.

Bone stared moodily ahead at the rain and the dripping hedgerows and at the shaft of the headlights probing the wet tarmac of the secondary road which would bring him in due course to The Towers.

He still had not solved the problem of the invitation. It really was most disturbing. It could not possibly bode well – only ill. But how ill? That was the question which had occupied Bone’s mind all Friday night and all Saturday and was still, at about seven o’clock on Saturday evening, involving him in anguished speculation.

He had the note in his pocket now. He had carefully brought it with him just in case there had been some ghastly mistake. In case it had been meant for someone else, or for another Bone or perhaps for someone called Tone or Cone or even Bole. Directly the butler said, ‘I don’t think his Lordship is expecting you, sir’, Bone would nonchalantly pat his pockets. ‘I wonder if I kept the invitation. Ah, yes, let me see, here we are.’ Then, as the butler stammered his apologies, Bone would be firm. ‘There’s clearly been some confusion,’ he would say smilingly. ‘But I shall really be very glad to get back to London. Important supper party. If the car could perhaps take me back to the station. And please give my compliments to Lord Ower and show him the invitation. I’m sure it will all be cleared up on Monday. No. No. I’m afraid I must insist. Very kind, but I really must be getting back.’

But the chauffeur had definitely enquired ‘Mr Bone?’ at the station and had been quite sufficiently deferential and somehow the wording of the invitation 11typed by a secretary in that fat type used, so far as Bone was aware, only by Lord Ower and Sir Winston Churchill had been quite explicit.

Lady Ower and I would be very glad if you would come down to The Towers tomorrow evening and spend the night. There is an excellent train from Waterloo arriving at Maidstone at 6.45 and there will be a car to meet you.

O.

On the heels of the expensive white envelope brought down by one of the commissionaires on the fourth floor had come a telephone call from the social secretary, Miss Buckle. Yes, he would be delighted. No. A written acceptance would not be necessary. Bone had placed his elbows on his desk, had lowered his head carefully between his hands and while his mind raced he stared unblinking out of the office window into the November dusk.

Bone had been at Ower House for five years. Originally he had been taken on to buy serial rights in English and American fiction for the Big Five in the Ower chain, OurWomen(four million), OurFamilies(over two million), OurBeauty(just started and already past the million mark) and OurBodiesthe sturdy seed from which the whole crop had sprung. This once lively publication, progressively expurgated in step with its founder’s advancing wealth and station, had withered from over four million to 750,000 in the three years that it had taken plain Amos to graduate through Sir Amos to Lord Ower of The Towers, Bearsted, Hants.

A year after Bone’s arrival, Our World had been founded and Bone became its literary editor.

OurWorldwas designed to bring power and social advancement to Lord Ower whose title and riches had made him increasingly sensitive to jokes about his periodicals. In the old days when he was peddling pornography from his little press off the Charing Cross Road he had gladly suffered ribald enquiries for copies of ‘OurOldMan’ and worse, far worse. In fact he found they helped him to get advertising when he did the rounds of the truss manufacturers, the restorers of falling hair and arches and ‘vital forces’ every week and he would laugh jovially at each ghastly new jape and even invent and retail others so that he would seem clubbable and one of the gang. But those 12bad days were shrouded in the mists of time and now the jokes were more painful and for the matter of that more spiteful, particularly in the House of Lords where his rare visits unleashed a barrage of bad puns and ribaldry which only the man with a skin of an armadillo, which fortunately Lord Ower possessed, could have borne.

Then there was Lady Ower to consider – Belle Ower, a fine lower-middle-class woman from Guernsey with something of the presence and splendour of a Mrs Hackenabusch and with social ambitions that could only be described as atomic. Her most kindly soubriquet was ‘The Bellyful’, but it was almost a tradition at Ower House that anyone who was sacked should write her an anonymous letter in which ‘Our’ was conjugated with every obscenity in the book.

All this made Lord Ower put all his periodicals into a subsidiary company and transfer their publication to Manchester where they continued to prosper greatly but relatively out of sight of Westminster and Mayfair. Ower House was cleared of its nose-picking inky-fingered scriveners, Wilton carpet was laid in the corridors and the highest salaries in Fleet Street, laced with generous expense allowances, soon filled it with one of the best second-class newspaper staffs.

For three months they worked in great secrecy, or so the proprietor imagined, on dummies until, just four years before Caffery Bone got his invitation to The Towers, OurWorldwas born.

Lord Ower was a very shrewd man and he hit on just that gap in readership which no other publisher had perceived or had had the courage to tackle. The formula, the weekend newspaper on sale on Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays, had already been vindicated when the Daily Mirror group started Reveille and ran it up to over three million circulation in four years. But that was a 3d. paper for the working classes and Lord Ower was after power and prestige rather than profits from mass entertainment. He aimed where Northcliffe would have aimed, at the new educated classes catered for at the weekend by the SundayTimesand Observer, and by the NewStatesmanand TheSpectator, and when he examined this field he discovered a significant, a very significant fact.

On weekdays, more educated people read adult newspapers than they did on Sundays. There was a gap, a fat gap to be filled for the asking. The Telegraphsold a million a day, TheTimes250,000, the Guardian150,000 – a total 13of 1,400,000 educated people. But the combined circulations of the SundayTimes and the Observer only came to a million and only about 100,000 read the NewStatesmanand TheSpectator. Even forgetting the high class readership of the NewsChronicle(1,500,000) and God knows what they read on Sundays, you still had a gift of 300,000 who appeared to dislike all the weekend reading. With OurWorld, aiming somewhere between the Observerand the SundayExpressand on sale for 6d. from Friday to Sunday, Lord Ower decided to round up that 300,000 like a sheep dog rounds up sheep and, he chuckled grimly, then start cutting into the quality Sundays as well.

And how right he had been, reflected Bone as he stared out of the window of his office just four years later. 400,000 in the bag, advertising rates up every six months or so, all the best writers stolen or bought from the Sundays and thanks to the Labour policy of the paper, a certain Viscountcy for Lord Ower when this government was out.

And Bone had risen with it until he was now the most sought after literary editor in London and certainly the best paid. Why, three thousand a year and five hundred expenses was almost as much as a cabinet minister and when one added on the sale of review copies, perhaps fifty a week, at several shillings a copy, and the innumerable free lunches with publishers and authors and reviewers, and occasional work for the BBC on The Critics’ Circle and so forth it all added up to being just as well paid as a cabinet minister, if not better.

And yet, and yet. On that Friday evening Bone had fingered the stiff sheet of Basildon Bond and had read again the invitation which he already knew by heart. And yet how impermanent it all was, how unstable, how fraught with inevitable doom and the certainty of the sack. The mere fact of appointment to Lord Ower’s staff was the first step down that steep place into the sea, not with the mad rush of a Gadarene pig, but with slow inching progress slipping down towards the rocks and foam through the samphire and the centaury, the campion and the thrift. For Lord Ower sacked everyone sooner or later, harshly if they belonged to no union or with a fat cheque if they did and were in a position to hit back. If one worked for Lord Ower one was expendable and one just spent oneself until one had gone over the cliff edge and disappeared beneath the waves with a fat splash. There was a moment’s hush in the big building, as there is in prisons at the moment of an execution, and then 14the cleaners would come in and prepare your office, your oubliette for the next man.

And Bone was ripe for it. He knew he must be because for one thing, of all the senior men on OurWorld, of all the possible targets, he had been there the longest, and that alone made him vulnerable enough. But worse still, only that morning had there appeared, threateningly over the horizon, a cloud maybe no larger than a man’s hand but in hue as devilishly black as the very pit. He had been discussing his pages with Waterhouse, the editor, when Waterhouse had suddenly looked up from the proof of a review by Angus Wilson and a short exchange of words had taken place which now, on reflection, seemed to Bone infinitely sinister.

‘I should take out “anal-eroticism”.’

‘But, good heavens, why? We’ve had it in before.’

‘Well, I just would, that’s all.’

And with a smile of sympathy, which Bone now saw had been a smile of pity, he put his blue pencil through the words.

It was all so exactly like the way Bone had often tried to save a contributor from dismissal, by juggling with his copy, cutting out phrases or opinions which might provide pegs for an ultimatum from Lord Ower (‘Mr. Bone, this man Madariaga must go. His last review caused great offence to the Spanish Ambassador’) or even by inserting, at the cost of many friendships and much self-respect, slavish reference to Lord Ower or his interests. Bone grimly remembered his successful and ingenious rescue of Frith, his poetry reviewer, who had unfortunately been seen by Lord Ower wearing a black tie at a ball in aid of the National Theatre which had been attended by minor royalty (‘Doesn’t do the paper any good, Mr. Bone. Not quite our man, perhaps’).

This had been on a Thursday evening with the paper just about to go to bed with a review by Frith of a new book on the life of Shelley which seemed to offer no loophole for any reference, laudatory or otherwise, to Lord Ower.

Bone, who liked Frith and knew that Frith’s wife had just had a miscarriage, sat at his desk in despair, desperately rummaging his mind for any means, however hideously inappropriate, of linking Lord Ower’s name with Shelley. Then he dashed down in triumph to the printing room and just caught the literary page on the stone.

Next morning a bewildered Frith read as the last sentence of his review: 15‘The author closes his fascinating study with a reference to the great poet’s death at the early age of 33. Curiously enough this is just a year short of half the age of that great contemporary patron of literature, Lord Ower, thanks to whose wisdom and generosity so much space on this page is devoted to the consideration of poets and poetry.’

‘I hear Mr. Frith’s work well spoken of, Mr. Bone,’ said Lord Ower some weeks later. ‘What money’s he getting?’

‘Twenty-five, Lord Ower.’

‘Don’t let us be parsimonious, Mr. Bone. Good men are hard to find. Make it thirty.’

And now, thought Bone, Waterhouse knew something and was doing his best to protect his literary editor. But what did he know? Had it only been a hint from Lord Ower that the literary page was getting a little ‘off-colour’ (Lord Ower’s euphemism for pornographic) or had there been a conversation rather like this: ‘Er, Mr. Waterhouse, what is your impression of Mr. Bone’s work?’

‘It’s very good, Lord Ower.’

‘Doubtless, Mr. Waterhouse, but is it the best available to us?’

‘Well, er …’

‘It has been suggested to me, Mr.Waterhouse, that Mr. Bone is getting lazy in his choice of reviewers. Confidentially, er, quite between these four walls, you understand, it has come to my ears that Lord Simonstown was very disappointed not to be asked to review Sir Winston Churchill’s last volume. Not the sort of man we want to offend, I’m sure you will agree.’

‘Certainly not, Lord Ower.’

‘He also seems to have been at pains to avoid commissioning work from Sir Ambrose Borrage, a name I would very much like to see in the paper. A very eminent public servant, I’m sure you will agree, Mr. Waterhouse.’

‘Yes, Lord Ower.’

‘Well, Mr. Waterhouse, perhaps we’ve had the best work out of Mr. Bone. I’d be glad to have your thoughts on the problem in due course. Let me have one or two names. We can’t leave an important part of the paper in bad hands particularly with the Christmas book season so closely upon us. Thank you. That’s all for now, Mr. Waterhouse.’

Had it been like that? Bone certainly felt guilty about Lord Simonstown. 16He had known that the dreadful man was a close friend of the Chief’s and that he had been furious when the Churchill book had been done, and done brilliantly, by Isaiah Berlin. And as for the unspeakable Borrage, that literary dung-beetle, that cringing hyena, he would sooner commission the children’s book reviews from the Dusseldorf murderer than allot him an inch of space on the book page. But then, it didn’t matter much what the excuse was. If Lord Ower got tired of your name in the paper or wanted to find room for some new protégé, any peg would do to hang the sack on.

And this invitation had certainly looked on Friday night, and still looked this evening, like the summons to the Last Supper, that dread meal to which senior men were always invited just before they were fired. And Bone had always admired the fiendish invention when its working had, early in his career at Ower House, been explained to him. It seemed such a brilliantly effective piece of inquisitorial machinery, so clean, so final and so devastatingly just and proper, like the moment of truth when the matador looks the bull in the eye and the path of the sword through the air is only a formality.

Take the case of John Dance, a former editor of OurWorld. Bone ghoulishly collected every detail he could of these Last Suppers and then polished them up into little case-histories for his private morgue. Dance drank too much, but he was an excellent editor and the only reason Lord Ower wanted to sack him was because Dance would not support the Labour Party right or wrong, and Lord Ower feared for his half-promised barony unless Our Worldfollowed exactly the political line of the DailyHerald. So Dance was invited to dinner and to stay the night at The Towers. Whisky was put in his bedroom and he naturally helped himself while he was dressing for dinner. A galaxy of fashionable and distinguished guests was assembled in the drawing room when he came downstairs, including, he noticed with alarm, two Labour cabinet ministers and a Bishop. He was offered a cocktail and drank it slowly and carefully but directly it was finished Lord Ower jovially pressed him to another. They went in to dinner and there was sherry with the soup. When he refused it, the butler seemed not to hear him, and before the next course, Lord Ower leant towards him.

‘Rather special sherry, don’t you think, Mr. Dance?’

‘Quite excellent, Lord Ower,’ said Dance and drank it with reverence.

With the fish came a heavy Beaune. Dance drank a glass and was surprised 17when the enigmatic butler filled it up again. There came a pause in the conversation.

‘And what do you think of my modest white wine, Mr. Dance?’ enquired Lord Ower. ‘Not too heavy for your taste I hope.’

‘Certainly not Lord Ower,’ said Dance, and hastily gulped it down.

Burgundy was served with the roast pheasant and again the unwary Dance finished his glass, only to find when he turned back from his neighbour that it had been charged again.

‘It’s very fortunate that you are here this evening, Mr. Dance,’ said Lord Ower a few moments later. ‘I’m trying out some new Burgundy. Now you’re quite a connoisseur, I believe. Give me your honest opinion of it.’

There was a deferential silence round the table while Dance went through the motions of savouring the wine and sipping it.

‘Ah, Mr. Dance, but with a Burgundy you must surely let it reach the back of the palate. Now,’ and Lord Ower fairly twinkled with joviality, ‘take a man’s draught, and let me know what you think.’

Dance obliged, but in his embarrassment, very nearly did the nose-trick. Lord Ower immediately called to the butler, waving aside Dance’s expostulations. ‘Jelks, a bottle of the ’45. This ’43 is clearly not to Mr. Dance’s taste.’

And so it went on through the sweet (‘Now Mr. Dance, which is your preference between these Yquems?’) to the coffee and brandy (‘They say it’s Napoleon, Mr. Dance, but I really can’t believe it. Can you?’) and all the while general conversation was proceeding round the table and no-one could have said that Lord Ower was being anything but a most solicitous host.

When finally they rose, it was without Dance. Quite plastered and totally oblivious to his surroundings, he just wanted to sleep, and, resting his head on his arms amid the glasses and the nuts, he knew nothing more until he found himself being carried to bed by the butler and one of the footmen.

Nothing remained to be said on either side. There was no need for goodbyes, let alone for a farewell cheque. In the morning, Dance quite naturally and humbly took the train for London, went to the office and collected his salary from the cashier, who appeared not to be surprised, and walked out into Fleet Street. The whole operation, he explained to Bone, just before leaving to take up a modest post on the NigerianEcho, had been as clean as a whistle and as just as the execution of a murderer.

18Bone had whistled, in sympathy, but also in admiration.

Miss Fairbanks, the editress of OurFamily, had been handled with equal brutality but greater finesse.

In private life a fervid supporter of Our Dumb Friends’ League and the R.S.P.C.A., all her frustrated parental urge and love of children was transferred to dogs, of which she kept as many as she could in the back garden of her suburban bungalow.

Now, on the face of it, there was absolutely no reason why Lord Ower should have know of this secret passion and therefore no reason to accuse him of bad taste or cruelty to Miss Fairbanks when, at a well-attended dinner-party at The Towers, at which she was one of the guests, he took a most decidedly zoophobic line when Lady Ower brought the conversation round to a recently published report on road deaths.

‘Nobody,’ Lord Ower turned with friendly concern to Miss Fairbanks who sat on his left, ‘nobody can be more distressed at the anguish caused to families by the loss of a dear one in this needless fashion than our excellent Miss Fairbanks, who is of course,’ he spoke to the table at large, ‘editress of OurFamily.’

Miss Fairbanks blushed in the sudden limelight and murmured her heartfelt agreement. Everyone assumed expressions of concern with the problem and sympathy with Miss Fairbanks’ distress at the casualties it caused amongst her readers.

‘There is a partial remedy,’ continued Lord Ower, ‘and,’ he beamed benignly, ‘I am going to take the unusual step of inviting Miss Fairbanks to propose this remedy, this partial remedy, in the leader columns of OurWorld.’ There was a murmur of assent and applause and Miss Fairbanks positively squirmed with pleasure, while making a small bow of flattered acquiescence. ‘My attention has been drawn,’ Lord Ower gazed sternly down the table, ‘to the fact that a sensible proportion, a very sensible proportion of these accidents is caused by loose dogs upon the highway. These dogs must,’ he slapped the table gently, ‘be put away, put, ah, painlessly away whenever they are found abroad. Only thus,’ and now Lord Ower was peaking in rich leaderese, ‘can our British families be spared a proportion, a sensible proportion, of these dreadful wounds.’

Amidst the qualified expressions of agreement which followed, the small 19cry of pain which came from Miss Fairbanks and the dumb weaving of her protesting hands went unnoticed even, apparently, by Lord Ower.

He turned and gazed blandly into her tortured eyes, and with a gesture of parental authority he silenced whatever she might have been about to say.

‘No, no. Do not be modest, my dear Miss Fairbanks. I have every confidence that you are quite up to the task which I have set you. What you write will be inspired, I am sure, by the very creditable sympathy you feel for the bereaved readers of OurFamily. No considerations, least of all bashfulness, will come, I know, before your paramount duty to your readers and to, ahm, to Ower House.’ Then, more firmly, ‘And let me see your copy first thing on Monday morning, please. Address it to me personally. This is a subject which is very close to my heart.’ And he glanced across to Lady Ower who immediately rose and swept the ladies out of the dining room.

That night, Bone reflected, when he heard the grisly tale, must have been sleepless for Miss Fairbanks. On the one hand, she must have argued, pacing her bedroom in her Jaegar dressing-gown, on the one hand certain dismissal (‘You have lost my confidence, Miss Fairbanks. The paper must always come first’) and on the other betrayal of her loved ones and the loss of her soul. And yet the leader would after all be anonymous. And it would certainly have no effect.

Miss Fairbanks wrote the leader on Sunday evening with a breaking heart but with fire in her pen and still she did not see the catch, the tails-you-lose, until Mr. Boot, the group editor-in-chief, sent for her on Monday afternoon.

‘Sit down Miss Fairbanks.’ Mr. Boot seemed genuinely, profoundly disturbed. He puffed busily at his pipe and his gaze hunted the wall above Miss Fairbanks’ head.

‘Miss Fairbanks, are you a supporter of the Dumb Friends’ League?’

‘Yes indeed, Mr. Boot,’ said Miss Fairbanks brightly.

‘You have many pets, yourself? Many little dogs?’

‘Oh yes, Mr. Boot. I love them.’

Mr. Boot quietly pushed a galley-proof across the table. Miss Fairbanks bent forward and a glance at the opening sentence was sufficient. Someone had added in bold type the heading ‘Our Dumb Enemies’. She blushed to the roots of her hair. Her limbs turned to water. She clutched the table. Finally she faced Mr. Boot. He sat looking at her coldly.

20‘But, Mr. Boot, Lord Ower told me to. I … I simply had to. I …’

‘Lord Ower knew nothing of your private life or your devotion to animals. He learnt of your hobby this morning. He is quite profoundly shocked, scandalised in fact by your extraordinary breach of journalistic ethics. He described it to me as the worst example of spiritual treachery which has ever come his way. I was only just able to prevent him from referring the facts to the executive of the National Union of Journalists. But for his generosity, it would certainly have been impossible for you to find another job in journalism.’

Miss Fairbanks burst into tears.

‘But it was he …’

‘Miss Fairbanks, I understand that it was quite a casual suggestion over dinner. Did you protest at the time? Did you try to avoid writing this leader? Did you put forward your point of view?’

‘No, but, but …’

‘Then I am afraid, Miss Fairbanks, that there is no more to be said. Lord Ower feels that something sacred has been betrayed. He asks me to tell you to try and strive higher in the future, wherever that future may take you. Your resignation is accepted. Good afternoon.’

And Miss Fairbanks had gone sobbing from the room.

Bone, when he heard the tale, was staggered by its simplicity and its neatness, like the snap of a handcuff, short, sharp and final. Compared with it the slaughter of the Reverend Percy Trimble, author of ‘From My Full Heart – A Weekly Handclasp’ which appeared in several of the Ower periodicals, had been almost clumsy, at the best inartistic. It was as if the simple cleric was thought to rate no better than a casual side-swipe of the mailed fist, but a knockout blow just the same.

On the Monday morning, as Bone understood it, after a particularly genial weekend at The Towers, the Reverend Trimble had entered his office at Owers House with the feeling that his stock was high with the Chief. Humming the opening bars of the Dresden Amen he sat down to his desk, packed his pipe with Barneys and turned to his voluminous mail on top of which lay a neat paper parcel about the size of a book, a review copy he supposed, until he saw that it bore no stamp or postmark but only his name and the superscription ‘absolutely private and confidential’, heavily underscored.

21Inside the top wrapper was a letter, on the heavy paper used by Lord Ower’s private secretary, and then another parcel, bearing the words ‘To be opened only by the Rev. Percy Trimble’.

The letter was from Linklater, the private secretary. It read:

Dear Mr. Trimble,

Lord Ower instructs me to return to you this book, which was found by one of the maids at The Towers under the pillow in your room after your departure this morning.

Would you kindly acknowledge its safe receipt.

Lord Ower instructs me to say that in the circumstances which he does not wish to discuss with you, your contributions to the group publications will no longer be required.

Yours faithfully,

Albert Linklater

Feverishly the Reverend Trimble tore the wrapping off the inner parcel. It contained a much thumbed copy of FannyHillwith etchings by Felicien Rops. A random glance at the rosy interlaced bodies was sufficient. Trembling, the Reverend Trimble snatched at the telephone.

‘Linklater speaking.’

A torrent of words poured into the apparatus. ‘… scandalous mistake … never heard of the book … who does he think I am … won’t stand for it … blackening my name … libel action … wrongful dismissal …’

Patiently, coldly, Linklater finally broke in.