Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

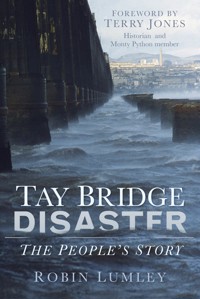

On Sunday, 28 December 1879, the 5.27 mail and passenger train from Burntisland to Dundee went out across the world's longest bridge on a black, fierce night, only to be dashed to pieces in the River Tay as the bridge collapsed during one of the worst storms in Scottish history. The Tay Bridge Disaster remains to this day the worst catastrophic failure of a civil engineering structure in Britain – the land equivalent of the Titanic sinking. In this book, author Robin Lumley brings a poignant human perspective to the fateful night in 1879 that shook Britain and the world of engineering to their core and sent a nation into mourning for the seventy-five souls lost to the dark, freezing waters of the River Tay. Packed full of personal tales and offering technical appendices for those who wish to further their specialised knowledge, Tay Bridge Disaster: The People's Story is a must-read for anyone interested in this tragic event in Scottish and British history.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 548

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Debra, Johanna, Charlie and Daniel and Robert Allanson (1929–2013)

And in memory of Bill Dow, ‘the Grand Old Man of the Tay Bridge’, who sadly passed away on 21 June 2013

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

Foreword by Terry Jones

Acknowledgements

Preface

Introduction

1 Working on the Railway

2 Tay to Forth: Across Fiobha, the Kingdom of Fife

3 Crossing the Forth

4 Duress Non Frango

5 Strangers on a Train

6 The Tay and Two Cities

7 The Rainbow Bridge

8 Heavy Weather

9 Iron and Cupar

10 The Last One Across

11 Train of Tumbrils

12 The Long Drop

13 Who Saw What?

14 Inquiry

15 The Rebuild

16 Coda

Appendix

Chapter Notes

Bibliography

Plate Section

Copyright

FOREWORD BY TERRY JONES

This is a stopping train, calling at all stations from Edinburgh (in the late nineteenth century) to Perth (in which town King James IV lifted the ban on playing golf in 1502) and Dundee (Perth’s great rival). On the way, the reader is taken on many detours down fascinating branch lines, as we follow the story of the ill-fated 5.27 Burntisland to Dundee train on that stormy night of Sunday 28 December 1879.

We get to know many of the passengers on that doomed train: giving us a peep-show of the lives of ordinary Victorian folk in stereoscopic detail, including Lady Baxter’s maid, Ann Cruikshanks, who, on that very day, may (or may not) have stolen her mistress’s entire collection of jewellery.

We discover the problems of early train travel – especially the perils of first-class passengers who were wearing rubber soles, and, when they reached their station, would find their feet stuck to their foot-warmers.

At the centre is the story of a reckless and arrogant designer, Thomas Bouch, and the catalogue of mistakes, errors of judgement and corner-cutting that led to the Tay Bridge Disaster.

After reading Robin Lumley’s detailed account of the correct method of iron casting, I feel like I’ve gone through quite an apprenticeship. I certainly now know that, when buying iron for bolts from the Cleveland Iron Works, ‘Best Iron’ is a euphemism for ‘Worst Iron’, since they grade their iron ‘Best’, ‘Best Best’ and ‘Best Best Best’.

Useful to know.

There is the dramatic story of the last train across, with the force of the wind ramming the carriages to the rails and producing showers of sparks, and the fact that the passengers and train crew wouldn’t know what a narrow escape they’d had when they reached the other side. And in the middle of the drama there is a wonderfully ludicrous moment, when the Rev. George Grubb, in the only first-class carriage, is subjected to a demonstration by a fellow passenger of the effect of opening a window facing the storm! If only they’d known how close they were to death.

And finally the fatal train itself makes its way across the already destabilised bridge, and meets its end plunging 88ft into the freezing black waters of the River Tay.

The final irony is that two of the members of the inquiry, sitting in judgement on what had happened, were hardly able to criticise the construction of the bridge, since they had approved Thomas Bouch’s designs, and indeed supplied information on which he had based those designs.

This is a slow train and not a 125mph express, with the result that you see more of the countryside, have more time to enjoy the details and ultimately have a more interesting journey for the same ticket.

Terry Jones

Terry Jones is a writer, broadcaster, historian, film maker and a founder member of the Monty Python team.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Serious and heartfelt thanks to everyone listed here, without whom the book would never have happened. For omissions I do apologise to anyone left out. But I must at the outset apportion some blame for the inspiration of this book. It’s all Kevin Ormsby and Julie Carter’s fault. Some years ago they ran a second-hand bookshop in Melbourne where I would occasionally browse and one day I bought a copy of The High Girders by John Prebble from them which jogged my memory about my great-grandfather Jamie Lee and his chance escape from death on the doomed train 133 years ago. Re-reading that book inspired me to write this one. Throughout the research and writing Kevin and Julie provided non-stop enthusiastic support.

So, big thanks to (and in no particular order):

David Kett, formerly Head of Reference Services at Dundee Central Library, who over the several years this book has taken to write, has been the prime mover par excellence in ‘on the spot’ research in Dundee. Ably assisted by Eileen Moran and the staff of the Dundee Local History Library, David has constantly come up with priceless information, gems of history and an ongoing e-mail dialogue about the whole subject of the Tay Bridge event, probably wearing out the library’s photocopy machine on my behalf. As time has passed, David and I have discovered much in common, not least a pleasantly warped and irreverent sense of humour. It is amusing to re-read the formality of our earlier correspondence and compare it to the lunacy of our current missives! Truly he is now a real pal and an utterly invaluable one for this book. I’ve constantly pestered him and probably been responsible for his early retirement and the shortening of his life.

Dr Peter Lewis, whose own book The Beautiful Railway Bridge over the Silvery Tay was published a few years ago: this is a paragon of meticulous forensic analysis about the Tay Bridge collapse, and Dr Lewis has been another long-term correspondent, providing a sounding board for some of my more madcap theories and allowing a healthy repartee with some sparky moments on the whole subject. He was kind enough to acknowledge this by including me in his own book’s ‘Thank You’ list, a fact of which I am most proud.

Ted Thoday is a magazine editor in his own right as well as being a walking encyclopaedia of all things railway, both model and 12in to the foot scale. He’s also a long-time friend and a great proof reader. Not only that, his constant faith in the project kept me going when I lapsed into despair. He was always there to supply the occasional gems of information. What a pal! Ta lots Teditor!

Alan Porter is a railway modeller with an encyclopaedic knowledge of the prototype. My thanks to him for always answering my questions.

Kylie Robertson rendered the map of the 5.27 train’s route on the fateful night. Using her formidable computing skills she transformed my biro scrawl into the cartographic perfection which now graces these pages. Many many thanks, Kylie!

Dr Mal Clark is another of those well-lettered chaps who didn’t mind demeaning themselves and having the patience to have long dialogues with a non-academic like me. Years of happy e-mail exchanges with Mal taught me lots, including how to remain wide-minded when perusing evidence. He must think I’m OK because we’re both busy working on the early stages of his own book about scapegoats in the world of engineering. If I can be of use to him, that will be small thanks for all the help he’s been to me.

Bill Dow, now a retired physicist, is the doyen of all Tay Bridge Disaster investigators. A local to the Dundee area, he’s been fascinated for ever by the night of 28 December 1879. His article in The Scotsman magazine in 1989 certainly inspired me to research further and although I haven’t always agreed with his conclusions, he remains the ‘Grand Old Man of Tay Bridge’ (that’s a compliment, Bill!) and he is someone for whom I have the deepest and greatest respect. I do so hope he enjoys this book, although he may fume a bit that an upstart should muscle in like this! In cahoots with Professor Rob Duck, Bill wrote the scientific paper on side-scan sonar analysis featured in the appendices. Rob is the only Dundee mentor I’ve actually met to date and is a geologist at St Andrews University. He helped me on the subject of river borings and is a splendid fellow. In fact absolutely everyone I’ve had dealings with deserves that epithet.

It’s said that one cannot choose one’s in-laws. Well that may be true but I couldn’t have been luckier with mine. My wife Debra’s parents, Bob and Beryl Allanson, have both been oracles for me. Bob is a retired steam locomotive driver and carefully checked all my footplate data while Beryl’s knowledge of historical clothing and footwear helped me immensely. Thanks to you both.

I’m very grateful to some folks who’ve been of significant help on specific subjects. Like husband-and-wife medical professors John Mills and Suzanne Crowe, who advised me on the physiology of drowning and burn damage to human flesh. And Professor Jeff Cooke from the Metallurgy Department of the University of Western Australia, who filled me in about casting iron and all the snags therein. Dr Dennis Wheeler from Sunderland University is a climatologist with a special interest in the impact of weather on historical events and through his correspondence I learned about the gusts inside a main storm that can wreak unexpected havoc. Thank you Dennis.

The help I’ve had from other meteorologists has been a tremendous boon. Like Sara-Jane Harris at the UK Met Office, who helped me decipher the language of synoptic charts, and the guidance from Bruce Underwood at the Australian Bureau of Meteorology.

You couldn’t write a book which involves the North British Railway without consulting the NBR Society, a historical club dedicated to that company. My contact there was Arch Noble, who was utterly marvellous in supplying information and a happy interchange of ideas. To him and the NBR Society as a whole, thank you all.

Ewan Crawford is a man who is passionate about the history of Scotland’s railways. His website RAILSCOT (http://railbrit.co.uk/) is a must destination for anyone researching that subject. But Ewan’s input went beyond allowing me to trawl his site; he’s been so very willing to help me personally. Ewan, you’re a star!

Thanks to Terry Jones for agreeing to write the Foreword after a bit of blackmail on my part. I reminded him that I’d sat through six episodes of his television series Ripping Yarns in one go (hardly a difficult task!) in order to help record a laughter track and he caved in, because he thought he owed me something. However, it’s nice to get an academic stamp of approval from such a well-accredited historian. Ta, TJ!

Audrey Brown at Kirkcaldy Central Library kindly provided loads of background information on Mr Linskill and his lucky escape from the train at Leuchars Junction, while the staff at Cheltenham Library sent contemporary newspaper clippings all about William Henry Beynon. All other books have him as ‘Benyon’, so I’m glad that his name has finally been spelt correctly in print.

Ian Nimmo White and Stuart Morris, Laird of Balgonie, have both been involved with the setting up of permanent memorials to the Tay Bridge victims and were most helpful to me.

Earlier in my research, Angus Kidd and I had a lively e-mail correspondence in which his local knowledge proved to be a boon. Ta, Angus!

Dundonian Cliff Blackburn, now a resident of Western Australia, gave me a large-scale streetmap of Dundee, which enabled me to work out the routes the people in the book used to get to work or to their homes. He also sent me a little book of historical Dundee photographs which helped to flavour my descriptive prose.

Janette Fly discovered the details of John Gosnell’s toothpaste containers while wandering through a Titanic artefacts exhibition.

Felicity Allen, an author in her own right, was kind enough to peruse some of my early drafts and helped my learning curve as a first-time writer in no small way.

Robert Styles has been a lifelong friend and eagerly followed the progress of my book, supplying constant encouragement and impetus. I hadn’t heard of the Ashtabula Bridge Disaster in the USA but Robert turned me on to it and I was able to incorporate the event into my story. Full marks, brave Sir Robert!

Andrew Holmes is a London-based film producer and supplied agent contacts for various ‘star names’ while I was searching for someone to write the Foreword.

Professor Charles McKean was a source of advice and vignettes concerning Tay Bridge, while Professor G. Sewell has written several books on NBR rolling stock. I happily used the information they supplied.

Historian David Swinfen has written his own book, The Fall of the Tay Bridge, which I gleefully raided with his permission.

Friend and neighbour Mick Bolto, himself a consummate man of letters, read a late draft and gave me some excellent advice on pacing and content.

Ian Biner, another old friend and author, was always there at the end of a phone to urge me forward on those occasions when I was flagging somewhat.

Jan van Schaik lent me a plethora of coloured diagrams on the workings of the Westinghouse Brake System, which cleared up a lot of mysteries for me.

Pillaging access to Alistair Nisbet’s photographic archives was most kindly permitted by the man himself and I have availed myself freely! Many of his pictures have never been published. Finding such items is always a problem with illustrating a book about the Tay Bridge. Alistair’s private archive solved everything. He is also the author of magazine articles and papers on the Tay Bridge subject and is a fellow aficionado of the event. Small wonder he’s turned out to be an e-mail friend at the very least and I’m very much looking forward to meeting him in person. So many thanks to Alistair Nisbet for all his photos and his efforts in sending them to me: my book is very much the richer for their inclusion.

Anna Carmichael and Chloe Day are my UK agents at Abner Stein who have been indefatigable in their help at the latter stages of the book. The History Press has an editor in Chrissy McMorris who is second to none and who imaginatively thought up the book’s title when I floundered and couldn’t think of anything new.

Finally the two most important girls involved: without my wife Debra Allanson and her long-term help with my analogue and non-computer mind I’d have tried to write this in longhand, I’m sure! Sorting out my pagination problems, proof-reading and general morale boosting were fundamental assistances which ensured an arguably sentient manuscript. She also endured seven years of rooms cluttered with research notes, piles of reference books and sheaves of NBR timetable photocopies from the National Archive of Scotland amongst other mess-making impedimenta. Debra put up with all this in a highly patient manner although, as a neat and tidy worker herself, her temper was probably bordering on homicidal.

Finally Lyn Tranter, my indefatigable agent who runs Australian Literary Management in Sydney and with only a ten-page resumé of the projected book, took me on as a client. Somewhat reckless of her I thought at the time, me being an unpublished first-time author. Even when I defaulted many times on deadlines, she always patiently kept the faith with the project and has endlessly supplied morale boosts when my enthusiasm flagged, as well as constantly providing valuable editorial advice. Always available on the end of a phone when I ran into problems, she was ever a mentor and ideas person and has now become a friend. Lyn made this book happen and for that I am deeply in her debt.

PREFACE

In 1879 a man called Jamie Lee lived at number 83 Peddie Street, Dundee, Scotland, only three doors away from a man called David Mitchell who was an engine driver for the North British Railway (NBR) Company. These men’s fates are bound together in this tale. Mr Lee was a butcher by trade and owned a number of shops in Dundee and across the county of Fife. Apart from a wife, he had a cat, a ferret, two white mice and a canary. His children had not at that time been conceived.

Early on the morning of Saturday 27 December 1879, he paid 12s 9d for a first-class return railway ticket from Dundee to Burntisland. He was on his way to a meeting with some business associates which was scheduled to be completed by the following day, when he planned to return home to Dundee. But the agenda took longer than anticipated, the meeting continued throughout Sunday 28 December and Mr Lee decided to postpone his trip home to Dundee until Monday morning, 29 December.

So it was that he didn’t catch the Sunday 5.27 p.m. Burntisland–Dundee train. As it was this locomotive and carriages which fell with the great Tay Bridge that night, killing everyone aboard, Jamie Lee believed he could discern the ‘Arm of Providence’ at work, preserving his life when so many had perished. So he kept the unused return half of the ticket in his wallet for the rest of his days as a reminder of God’s hand, his own mortality and proof that miracles can happen.

When I was a very small child growing up in Rosyth, Fife, in the early 1950s, Jamie Lee’s son, by then an old man, showed me the ticket that had been passed to him by his father. The son in this anecdote was my grandfather and Jamie Lee my great-grandfather. By not catching the 5.27 p.m. train that Sunday night, Jamie enabled my birth sixty-nine years later.

Ever since then, I have been entranced by my grandfather’s story of the primitive little steam engine pulling its train of tiny fragile wooden carriages which were only a small step up from stage coaches. Lit by guttering paraffin lamps, they lurched bumpily along on their four and six wheels, a world away from the monocoque, all-metal, air-conditioned, neon-lit bogie coaching stock of the twenty-first century. Out they went across the longest bridge in the world on a black fierce night, only to be dashed to pieces into the River Tay during one of the worst storms in Scottish history. The Tay Bridge Disaster remains to this day the most catastrophic failure of a civil engineering structure in Britain – the land equivalent of the sinking of the Titanic, given its repercussions not only in Britain but around the world in the sphere of engineering. Indeed, there are many parallels between the Titanic and the Tay Bridge Disaster: hubris, arrogance, incompetence and the ignoring of warning signs to name but a few.

Previous and subsequent accidents have taken a far heavier toll of human life and have caused a stir for a time, only to be forgotten. A good example is the SS Princess Alice disaster of September 1878.1 This accident occurred just fifteen months prior to the Tay Bridge collapse. Over 600 people (more than seven times the death roll in the River Tay) were drowned in broad daylight on a sunny summer Sunday evening in the River Thames near Woolwich. Yet this terrible catastrophe is now largely forgotten, while Tay Bridge has entered the world of legend.

This book’s narrative takes the form of a journey on the out-and-back ‘Edinburgh’ train from Dundee to Burntisland and return – well almost. This format enables us to meet many of the passengers and crew who would lose their lives in the disaster to come, as well as railway employees like signalmen, wheel tappers, stationmasters, ticket collectors and engine shed staff. As the trip progresses, we sidetrack to learn about the factors involved in the demise of the Tay Bridge. For example, how the great storm that blasted Scotland that night developed and why, the current state of weather forecasting, the character of bridge designer Thomas Bouch, the story of how the bridge was built and the intense rivalry between the two cities of Perth and Dundee, and how that affected the way the Tay Bridge was constructed. At the heart of the whole story is the River Tay itself and so we’ll learn of its influence on the whole matter. I’ve been able to weave into the narrative many pieces of Scottish history and observations on Scottish life at the time, including some fascinating anecdotal material concerning the city life of Edinburgh, Perth and Dundee, all of which, while being background, serve to enrich the whole story and add to the tapestry of the minutiae of a Victorian age now long gone.

This book is designed as a kind of living history to give readers an experience of the Tay Bridge event that is subjective and to make them feel part of it. Back then people were doing things that folk today will understand because in similar circumstances they may have reacted in the same way.

Period books tend to focus on the differences between ‘then’ and ‘now’. But folk were the same. Human nature was the same. People’s loves, hates and fears were the same.

Connecting to a momentous event in this way gives so much more resonance if the reader is there and aboard the train, as it were.

C.P. Scott, the editor of the Manchester Guardian in 1916, advised his journalists: ‘comment is free but facts are sacred.’

In writing Tay Bridge Disaster: The People’s Story, I have tried to adhere to that precept.

An old proverb used by Josephine Tey (pronounced ‘tay’) as a book title in 1955 says it all, since I’m writing this from a distance of over 130 years from the event: ‘Truth is the daughter of time.’

INTRODUCTION

AD 1879: THE YEAR IN PERSPECTIVE

To put 1879, the year of the Tay Bridge Disaster and the forty-second year of Queen Victoria’s reign, into a historical perspective, here’s a list of some of the events, anniversaries and trivia that occurred during that year, so one can see just what was going on in the world at the time.

In Britain, people were having a rough time in socio-economic terms compared to the present day with much of the population in bad health. Many suffered from tuberculosis, cholera, whooping cough, scarlet fever, measles, syphilis and a host of other infectious diseases. A man in the industrial working classes might only expect to live on average to thirty-eight years. Agriculture, once the main source of work, had been in decline for many years and by the 1870s less than 15 per cent of the population was still so employed. Many in these social strati decided upon emigration to pastures new, such as Canada and Australia. Disgruntled young men joined the army where, although discipline was severe and flogging still extant, they did have at least regular if paltry pay plus food and quarters. At the time of our story, the Prime Minister of Britain was the Conservative Benjamin Disraeli, whose government had held power since 1874.

The year 1879 saw the birthdays of some significant people, several of whom would have a great influence in the new century to come. Amongst these was writer Edward Morgan Forster – E.M. Forster, later to struggle with his homosexuality of which we only recently have cognisance – who shared a birthday on 1 January with William Fox, the founder of the Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation. Two giants of Communism breathed their first in that year: Josef Vissarionovich Dzhugashivi – later known to the world as Stalin – in Gori, Georgia on 21 December, and Lev Davidovitch Bronstein in Ianovka, Ukraine on 7 November; subsequently he would call himself Leon Trotsky.

Albert Einstein was born in Ulm, Germany on March 14, Paul Klee, the influential expressionist and surrealist painter, in Munchenbuchsee bei Bern, Switzerland, on 18 December and Frank Bridge, the British composer, arrived into the world in Brighton on 26 February.

Canadian Max Aitken, later in life Lord Beaverbrook, the newspaper magnate and Minister for Aircraft Production during the crucial months of the Battle of Britain (1940), was born on 26 March.

In the world of politics and warfare, after the catastrophic defeat of a British army at Isandlwana, South Africa by Zulu forces under King Cetewayo on 22 January, the following day saw the now legendary successful defence of the mission station at Rorke’s Drift by a handful of the South Wales Borderers under Lieutenant John Chard. This became the subject of Stanley Baker’s classic 1964 film, Zulu. The Zulu Wars ended on 4 July when Lord Chelmsford’s army defeated King Cetewayo at Ulundi. A peace treaty was signed on 1 September. Two days later and in another part of the world, Afghani forces massacred the British Legation in Kabul and the British invaded Afghanistan in October in an attempt to restore order, an activity which is still ongoing and an example of the lessons of history not being learned which, as we’ll see, was a factor in the fall of the Tay Bridge.

Meanwhile, Chile invaded Peru and Bolivia on 1 November. Between 24 November and 9 December in Scotland during the Midlothian constituency campaign, opposition leader and Scot William Ewart Gladstone denounced Disraeli’s government for imperialism and the mishandling of domestic affairs. The fall of the Conservatives came very soon after in 1880, helped to some degree by the stigma of the Tay Bridge Disaster.

An alliance between Germany and Austria was signed in Vienna on 7 October.

Science and inventions had a bumper 1879. German physician Albert Neisser discovered the bacteria responsible for gonorrhoea, US chemist Ira Remson discovered saccharin (which is 500 times sweeter than sugar), Henry Fleuss developed the first self-contained oxygen re-breather for divers – the forerunner of SCUBA, the acronym for Self-Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus – and Scotsman Dugald Clark invented the two-stroke petrol engine. Mitosis cell division was observed by Walter Flemming. On 4 November American bar owner James Jacob Ritty of Dayton, Ohio, patented the cash register, known as ‘Ritty’s Incorruptible Cashier’, while French engineer François Hennebique was the first to use reinforced concrete for floor slabs. Chemist Robert Chesebrough produced a petroleum jelly he called Vaseline. Werner Von Siemens demonstrated the electric street car in Berlin and Thomas Edison turned on the first electric light bulb in the USA, as did Joseph Swan in England – both illuminations in October. And the first telephone exchange for general use, as opposed to business use only, opened in London during August.

Amongst important personages’ death dates in 1879 were Rowland Hill (of Penny Black postage stamp fame) on 27 August, Saint Bernadette of Lourdes on 16 April and William Lloyd Garrison, anti-slavery campaigner, on 24 May.

When Scottish physicist James Maxwell Clerk, who was the pioneer of electromagnetic theory and who ushered in the age of modern physics, died on 5 November, it was a significant loss to the field of science.

Finally, here are a number of interesting things happened in the year that fall into the ‘miscellaneous’ category:

The Bishop of Durham proudly announced that the world was created at 9 a.m. on 23 October, 4004 BC.

The use of the ‘cat o’ nine tails’ lash as a Royal Navy punishment was abolished.

The British Goat Society was formed.

In Britain, Henry John Lawson marketed the ‘safety bicycle’, recognisably the forerunner of the modern bicycle, with pedals and a chain-drive. It cost around £12, about five weeks’ wages for an ordinary British working man in 1879.

The first Bulgarian postcard was printed on 1 May.

An eccentric jeweller in Iowa, USA, invented the airbrush.

Gilbert and Sullivan’s comic operettas HMS Pinafore and The Pirates of Penzance were both premiered.

The science of psychology was founded by Wilhelm Wundt of Leipzig while, again in Germany, Wilhelm Marr coined the term ‘anti-Semitism’.

The first funicular railway was opened on the slopes of Mount Vesuvius, Italy.

On 19 July, ‘Doc’ Holliday (made famous by the film based on true events Gunfight at the O.K. Corral) killed his first man in a shoot-out, and 30 May saw the renaming in New York of Gilmore’s Garden to Madison Square Garden. Still in the USA, a businessman called Frank Woolworth opened his first ‘Five and Dime’ store in Utica, New York State. His businesses were to proliferate worldwide as Woolworths and eventually Safeways supermarkets to this day (although in the UK Woolworths is not now trading, and Safeways has been taken over by Morrisons supermarkets).

On Monday 29 December, an 18-year-old badly deformed youth named Joseph Carey Merrick, later to be known as the ‘Elephant Man’, was admitted in a state of destitution to the Leicester Union Workhouse on a day when the whole of Britain was in shock, reeling from the ‘morning after’ news of the Tay Bridge collapse. That event provided the sorry climax to 1879.

1

WORKING ON THE RAILWAY

Unlike the motor car, which can be adequately controlled by a backward child, the steam locomotive needs intelligence and man-handling if it is to run at all.

Dr W.A. Tuplin

Dundee, Scotland, 5 a.m. Sunday 28 December, 1879. A cold, pitch-black winter’s morning and the upstairs bedroom windows at 89 Peddie Street were steamy with condensation. Mr and Mrs David Mitchell were fast asleep, but a continuous thudding noise against the glass panes woke David and made him scrabble in the dark for his matches.

Outside on the front wall below, a 14-year-old boy was wielding a long broomstick handle with a wad of cotton waste bound to the top end. He gently bumped this against the window glass, hoping that Mr Mitchell would wake up quickly so that he wouldn’t have to stand for too long in the chilly morning air. The sheets of old newspaper that were swathed around his legs and body beneath his clothing were marvellous for keeping out the wind but he was still very cold.

With the bedside candle now glowing through the window, the lad knew at once that Mitchell was up and about. Off he went to bang at another man’s window, for he was a ‘knocker up’ or callboy from Dundee North British Railway engine shed and every night he scuttled around the streets in the wee small hours to wake up engine crews rostered for early duties.

David Mitchell and his family had been living in Peddie Street since moving across the river from Tayport (formerly called Ferryport On Craig) nineteen months earlier. This was just as the ‘Stupendous New Tay Railway Bridge’ had opened as ‘The Wonder of The Age’ as the North British Railway described the structure in its advertising material. Indeed, the bridge had been the very reason for their moving home, for Mitchell was an engine driver for the North British Railway Company.

The son of a miller at Balbirnie Flour Mill in Leslie, Fife, 37-year-old Mitchell was a senior member of the locomotive department and, as such, earned about 7s a day. He drove the prestigious express trains between Burntisland and Dundee, nicknamed ‘The Edinburghs’, as they connected with the Edinburgh ferries crossing the Firth of Forth. He’d done the same sort of trips before the bridge opened and when Tayport had been the northern terminus but now, with the railway link extended across the Tay, he was based at the newly built Dundee (Tay Bridge) Engine Shed, just under a mile’s walk from his front door.

The duty Mitchell had pulled today was irksome. He was to take the out-and-back run of the Sunday ‘Edinburgh’, a turn of duty which he often performed. Ironically, this particular Sunday he wasn’t actually rostered for the job but had swapped shifts with Driver William Walker as a return favour for a previous exchange of duties. How such little moments decide life for one man and death for another … and this was indeed going to happen again on this raw morning as we’ll see.

On a weekday, his usual ‘Edinburgh’ train was scheduled to leave Dundee Tay Bridge station for Burntisland at 1.30 p.m. There was only a two-hour layover there until the train returned to Dundee at 5.02 p.m., having met the Edinburgh passengers off the ferry across the Firth of Forth from Granton.

But on Sundays the timetable was very sparse, with only two Edinburgh services each way as compared with eight on a weekday. Scottish railway companies, under pressure from the Sabbatarians, found it convenient to discourage Sunday travel. It seems that tardiness and discomfort were deliberately contrived. Branch line connections were few and infrequent – in fact most branch or feeder lines didn’t run on Sundays at all. Mitchell’s outward trip began at 7.30 a.m. and involved an eight-hour wait at Burntisland until the homeward leg at 5.27 p.m. With the need to book on ninety minutes before departure for engine preparation, this meant a total duty time of over fourteen hours, much of it mooching around at Burntisland, where there was really nothing to do. A gloomy ferry port in the middle of a winter Sunday was no place to be stuck all day but at least the enginemen could have an afternoon nap in the shed crew room.

Having lit his bedside candle David rolled out of bed, trying not to disturb his sleeping wife Janet. Mitchell, along with the rest of the working classes, couldn’t afford the new-fangled gas lighting which illuminated the streets and the houses of the wealthy.

Dressing quickly, he took a perfunctory wash, using the china water bowl. Then, thanks to a Christmas present just three days ago from Janet, he cleaned his teeth with John Gosnells’s Cherry Toothpaste, which came in a pale grey ceramic bowl with a lid. The wording on the top of the container proclaimed that the contents were ‘For beautifying and preserving the teeth and gums as well as being extra moist’ and that the ‘Cherry Toothpaste is patronized [sic] by The Queen’. In 1879 this was an expensive gift.2

Mitchell savoured the cherry taste as he brushed his teeth with a bone-handled toothbrush with horsehair bristles. Then he tiptoed towards the stairs.

On the way, he couldn’t resist taking a quick peek into the other bedroom where his children, boys David, Thomas and Andrew, aged 8, 7 and 5 years respectively, and wee 2-year-old lassie Isabella were all sleeping soundly. The youngest, Margaret, was still a babe-in-arms and slept in a cradle in her parents’ bedroom.

David Mitchell Junior had kicked out his blankets during the night so Mitchell Senior gently tucked his lad in once more. Smiling softly to himself, he went downstairs to make some breakfast and find his food for the rest of the long day ahead.

After lighting the kitchen oil-lamp, he raked through the glowing embers of the cooking-range fire and, with a couple of lumps of coal, soon coaxed it back into life. Mitchell put a kettle of water on to boil and opened a drawer in the kitchen dresser. The drawer was lined with thick brown paper and contained several soft grey lumps of cold porridge and buttermilk, each about the size of a cricket ball.

Janet had made these the night before, along with some ‘potted hough’ which was a stew of meat off-cuts and pig’s trotters that had now set solid in its own gelatine. Mitchell cut off a sizeable wedge, selected a couple of porridge lumps and wrapped the lot in more brown paper. He placed the little parcels in his food (or ‘tummy’) bag, sometimes called a ‘piece box’. For pudding, he made up some ‘jeely pieces’ – basically jam or marmalade sandwiches. These were a popular working-class dessert ever since the firm of James Keiller and Sons had begun producing marmalade and jam in Dundee at the dawn of the nineteenth century. Now the company’s factory in Chapel Street exported the preserves all over the world.

While waiting for the kettle to boil, Mitchell took a cardboard packet of Epp’s Cocoa Powder from the larder and tipped two liberal spoonfuls of it into a mug. He idly scanned the wording on the packet which extolled the virtues of Epp’s Cocoa as an excellent breakfast: ‘a delicately-flavoured beverage which may save us heavy doctor’s bills.’

With the boiling water, he made both his breakfast cocoa and a pot of tea, which, after cooling sufficiently, he decanted into two empty whisky bottles to be enjoyed as his drink while on the footplate of the engine. The tea would be drunk cold and without milk or sugar, for the era of the tea-can for footplate brew-ups was many years in the future – during the Second World War, in fact.

Warmed against the raw morning by his cocoa, Mitchell set off into the darkness and down the hill towards Perth Road and Nethergate, thinking that Sunday duties were a bit of a nuisance for a family man such as he. No matter, he’d be back home just after eight that night and would at least be able to tuck in his brood with a quick bedtime story: with his children all being under 10 years old they still believed in magic and fairytales. Then he would have a bite of supper with Janet, and some peace and quiet. For Mitchell was a sober and careful man with a gentle face and he had a great love for his family.

But now, the crisp December air was in his lungs as he walked purposefully to work to earn his 7s a day, dressed in clean white moleskin trousers, tweed peaked cap, blue pilot jacket, strong boots and a dark tweed waistcoat with albert watch-chain clinking. What with his jaw-line beard in the fashion of the day, he looked every inch the professional railwayman he most certainly was. A little earlier, his workmate for the day had left his own home at 18 Hunter Street, just over half a mile from the engine sheds. Bachelor John Marshall was 24 years old and had eight years’ service with the North British Railway, first as an engine-cleaner and now as a fireman.3

Mitchell and Marshall worked easily together on the footplate, as teamwork was essential in every way to the successful operation of a steam locomotive. Indeed that bonding continued in off-duty hours as the tall young fireman with dark hair was a frequent and welcome visitor to the Mitchell fireside. There, the talk was inevitably about engines, engines and more engines: the types and classes on the North British compared with those on the rival Caledonian Railway, their features and foibles and every aspect of driving and firing them.

Janet Mitchell often remarked that she might as well be living in the engine shed itself and if railwaymen lavished half the care on their womenfolk as they did on their engines, then there wouldn’t be a happier set of wives in the world! But at least husband David’s earnings from driving engines had enabled her to buy a new mangle from G.H. Nicholl’s Ironmongery Store in Bank Street. The Monday washing day chores were thus made a little easier and the big iron machine with its winding handle now dominated the kitchen.

Mid-Victorian enginemen were the elite amongst the ranks of the working class. Recently enfranchised in 1867, they were on a par with the policeman or schoolteacher: respectable, sober and God-fearing. The craftsmen of the steam age, they didn’t just go to work as other men did – they ‘proceeded to go on duty’.

It was the high noon era of engine smartness, with the gleaming brass and paintwork only seen nowadays on preserved railways. Engine cleaning, using ‘sockers’ of cotton waste and tallow, was a ritual strictly supervised and scrutinised. Dirty and unkempt engines were almost unheard of on goods trains, let alone on passenger services.4

Not only were the driving wheels and spokes cleaned but also the areas behind the spokes received attention. The inside-cylinder covers were scoured with brick dust until they shone like chrome.

Smoke box rings, brackets, dart handles, handrails and buffers all received the same treatment. The engine-cleaners would climb onto the smoke box footstep and pull themselves up by the grab rail until they could stand precariously on the boiler barrel itself, clasping the chimney to polish it, and the brass whistles at the front of the cab roof were burnished until they gleamed.

Unlike today, fourteen-hour shifts for enginemen were not uncommon. One driver spoke of being on pilot-engine duty for forty hours and complained, not surprisingly, that his faculties were impaired. When he reported his condition to his Superinten- dent, he was asked to retract his words or face dismissal. He refused and was fired!

Fatigue was found to be the cause of a nasty accident in 1873, in which the guard of the train had been on duty for nineteen hours and the driver and fireman had clocked up thirty-two hours. Some drivers had only six hours of sleep in a week.

In 1877, a Royal Commission was set up to investigate railway accidents and staff fatigue was found to be a frequent cause. The Commission displayed a peculiar reluctance for ‘any legislative interference prescribing particular hours for railway working’. Instead, the Commission thought: ‘It must be left to the companies to work the men as they feel best and most convenient.’

Often there was no proper uniform issue and a driver could be fined if his train arrived late or if he let an axle box run hot.5 However, pride in their craft and job security motivated the men over and above any of these hardships. One railwayman reputedly went to church on Sundays proudly carrying his shunter’s pole as his badge of office, so that all should know what he did.

So it was that, having enjoyed a pleasant if dark walk along Nethergate, passing the Morgan Tower and the new Gothic slab of St Andrew’s Roman Catholic Cathedral, David Mitchell turned down the lane leading to the Caledonian Railway’s engine shed at Dundee West station (the terminal of that line coming from Perth), passing in front of it and across its tracks to reach the NBR Tay Bridge engine shed which, named like the railway station lying adjacent to it, was a brand-new structure built for, and at the same time as, the bridge was constructed.

Greeting James Robertson, the Locomotive Shed Foreman, with a cheery, ‘Here for the Seven-Thirty’, Mitchell booked on duty at around 6 a.m., ready to drive the 7.30 a.m. departure for Burntisland. The round trip, which carried Her Majesty’s Royal Mail in both directions, was over by 7.20 p.m. on arrival at Dundee and was the last main-line train due to cross the Tay Bridge on a Sunday night. The last scheduled movements across the bridge were the branch-line trains to Tayport, the ‘church trains’ as they were nicknamed, leaving Dundee at 8 p.m. and returning by 8.50.

All very normal indeed – a rather ordinary train stopping at all intermediate stations, not really running to express schedules as if the North British Railway was loath to disturb the lethargy of a Scottish Sunday. So Mitchell concluded that he should be back home in the bosom of his family by mid-evening, as usual. What wasn’t usual was the choice of engine for the train.

Mitchell was informed that the previous night Locomotive Inspector James Moyes had failed engine No 89 Ladybank (or perhaps it was No 314 Lochee – accounts vary on this point) because of a minor mechanical fault. The small 0–4–2 tank-engine had been diagrammed6 for the job as was normal for the lightly laden Sunday ‘Edinburghs’.

David Mitchell carefully read the ‘Special Notices to Enginemen’ board, which listed any temporary speed restrictions, permanent way work, changes in signalling or alterations to timings. He then called in at the stores to draw oil bottles (actually made of tin) plus cotton waste in quarter-pound balls for cleaning hands and wiping down control levers. He found his mate John Marshall already busy preparing the replacement engine which Moyes had earmarked the night before and pronounced to be in first-class condition.

It was No 224, a 4–4–0 tender engine designed by Thomas Wheatley and one of a pair on the North British with that type of wheel arrangement. Built in 1871 at Cowlairs Works in Glasgow, Nos 224 and 2647 were now specifically diagrammed to work the weekday ‘Edinburghs’ and usually had Sundays off for minor maintenance and tube cleaning.

She was not a particularly big steam railway engine by twentieth-century standards, but for her day, No 224 was quite a monster. Sitting on the rails, she stretched along 27ft 6in of track, with another 17ft 10in of tender. She was powered by two inside cylinders, each measuring 17in bore by 24in long each in large iron castings. Considered in comparison to your car, it would be like having two dustbin-sized cylinders under your bonnet instead of an engine block.

The engine, including the boiler, which had 208 heating tubes running its length, and the firebox with a grate area of 15.75sq. ft, was carried on four 6ft 6in diameter driving wheels suspended on laminated springs under each axle box. Via connecting rods, the two inside cylinders drove the front crank axle.

Power was transmitted to the rear axle by a pair of coupling rods on the wheels themselves. A bogie of four 2ft 9in solid cast-iron wheels held up the front end. This front bogie helped to ease the engine through the sharp curves that abounded on the North British main line across Fife.

No 224 weighed 37 tons 1cwt in full working order – that is, with her boiler filled with water and her firebox stuffed with half a ton of incandescent coal. Of this weight, some 22 tons 8cwt was available for adhesion through the four-coupled driving wheels centred 7ft 7in apart. She towed a six-wheeled tender weighing in at 24 tons 17cwt, which was the supply cart for both firebox and boiler, carrying 3 tons of coal and 1,650 gallons of water.

She looked very handsome in her coat of pea-green paint, lined out in black and white. Her tender sides sported the gold letters ‘N B R’ and her combined number and works plates in cast brass were bolted to her cab side-sheets. The big dome on top of the boiler barrel was to collect the steam generated by the boiler itself and inside the dome was the regulator valve, which apportioned the amount of steam to reach the cylinders. The safety valves, which ‘blew off’ excess steam when full boiler pressure had been reached, were also fitted inside the top of the dome.

Imagine you are aboard No 224’s footplate and watching how the enginemen worked. The driver would be standing on the left side of the footplate with the fireman on his right in keeping with standard British railway practice. An exception was the Great Western Railway, whose footplate men stood the other way around.8

You’ll notice that the controls for a nineteenth-century steam engine were very few and basic. You’ll also notice that they all seem too robust and heavy for their purposes. This is because they have to withstand being belted with a coal pick, which is the most grab-able footplate tool to deal with a sticking control in an emergency. In the middle of the boiler back plate above the fire hole, the regulator handle controlled how much steam reached the cylinders, in effect the direct equivalent of your car’s accelerator. To the left by the cab side stood the 4ft-long steel reversing lever, which could be pushed forwards and backwards through several set positions of cut-off,9 these being marked on a brass quadrant. A ‘car’ comparison here would be the gearbox. In the middle of the boiler back plate, centrally positioned so that both driver and fireman could see it easily, was the boiler water gauge glass. This instrument was a thick glass tube standing vertically in a small metal frame. The water level in the tube corresponded exactly with the level of water in the boiler and was perhaps the most vital instrument on the footplate, considering the dire and literally explosive results should the water level be allowed to fall too low. In an emergency, if the gauge glass should shatter and no convenient moment was found to replace it, three test-cocks, mounted vertically above each other about 6in apart, could give a rough idea of the boiler water level.

Then there were two more levers on the driver’s side: the steam brake – which allowed steam-driven pistons to push cast-iron brake blocks against the driving wheels – and the other lever, that operated the Westinghouse continuous brake system.10

This ‘continuous brake system’ lever not only worked the engine brakes (through a device called a ‘triple valve’) but also all the brakes on the carriages of the train. The equipment was powered by compressed air from a pump fitted on the right-hand running-plate just in front of the cab, and this air was piped down the train by a series of flexible hoses. It formed a marvellous safety device because, should the couplings part and the train become divided, all the brakes would automatically go on and stop the train. The North British Railway was one of the earliest British companies to adopt this new American-designed system but by 1879 not all rolling stock had yet been fitted with it.

On the right side of the footplate was the live-steam injector handle. When the fireman turned on the water from the tender and then activated the steam jet to urge water via the injector into the boiler, there was initially a gurgling and then a sweet whistle. Footplate men have described this sound as ‘whistling like a linnet’.

Next to the injector11 was the blower control. Opening this tap allowed live steam to blow into the smoke box through a small-diameter copper pipe, pulling more air through the boiler tubes and thus the fire, acting like a set of bellows. Nicknamed ‘the fireman’s friend’, it was very useful if you needed to brighten up the fire and create more steam pressure in a hurry. Down near the floor on the right were the damper handles, which allowed the fireman to regulate the amount of cold air entering the fire grate from below, while down on the left were the cylinder draincock handles. As water cannot be compressed, any condensed steam in the cylinders could literally blow off the cylinder covers when the engine next moved, so on starting away, the draincocks were opened to allow any water to escape safely. Two small levers allowed dry sand to run down through pipes onto the rail under the driving wheels to prevent them slipping on wet days. The sand was stored in sandboxes, just under the running plate and in front of the leading driving wheel splashes on both sides of the engine. Finally, a pair of chains up in the roof sounded the whistles when pulled, one for goods, braking and shunting codes, the other for general warning use.12

There were but three instruments to watch. The steam pressure gauge was known as ‘the clock’ because it looked like one with its circular face graduated with increments of boiler pressure in lb/sq. in and indicated by a sweeping needle like the second hand on a watch. A red line against the poundage showed full boiler pressure and was the point when the safety valves, set at this maximum pressure, started to ‘blow off’ to vent excess steam. In No 224’s case this was at 150lb/sq. in.

The Westinghouse air gauge looked similar but its twin needles gave readings on the air pressure in the train pipe and the compressed air reservoir. The last instrument was the boiler water-level gauge or gauge glass, which we’ve just looked at above. There were no speedometers in use generally on British locomotives until the 1920s. Drivers were expected to ‘know’ how fast they were going.

Now Mitchell and Marshall didn’t have a little 0–4–2 tank engine as their mount, the two friends had to work a mite faster to prepare No 224, as she was a much bigger engine altogether. Booking on with the ‘wee tankie’ in mind, they’d allowed about an hour for the job, whereas the big Wheatley bogie would take longer to be ready for the road.

Unlike a diesel locomotive or a motorcar, both of which can be started with a key, a steam engine required a lot of skill and effort before it could move at all.

The cavernous engine shed had the stillness of a cathedral, with flickering weak gaslight cutting through the gloom to sparkle back from engines adorned with polished brass and copper. The peace was broken as Marshall’s shovel rasped through coal and the firebox doors were clanked open.

The fire had been lit a few hours previously by the night-turn shed crew. When he wasn’t ‘knocking up’ engine crews, the callboy would help with such duties. The firebox was lined with small lumps of coal, leaving a space in the middle. Firelighters, made from small strips of old timber nailed together and stuffed with paraffin-soaked cotton waste, were lit, placed on a shovel and lowered into that space in the firebox. Choice lumps of coal were then placed on top, the dampers opened and the firebox doors closed to within an inch. The gap increased the draught and brought the fire up more quickly. Four hours after lighting up, No 224 was on the simmer with about 40lb of steam showing on the pressure gauge, all ready for the fireman to build up his fire for the journey.

So now Marshall got out the pricker – which was like an overgrown domestic poker that was 8ft long – to reach right down the firebox and spread the fire more thinly over the grate. Thick ‘haycock’ fires are fine once on the road but don’t provide as much heat as a thin fire bed. With a half-turn on the blower, steam pressure soon started to rise more rapidly and No 224 was gurgling to herself and beginning to come alive. Meanwhile, Mitchell had disappeared into the access pit under the engine with his oil-feeder and a flare lamp to see his way. He filled up lubrication pots, checked the worsted trimmings13 and bearings and made sure that the ash pan wasn’t clogged. He called up to the footplate to get Marshall to move her forwards an inch as the spokes of the driving wheels were fouling his reach to the axle-box oilways. With Mitchell’s arm stretched through those spokes, there could be no risk of the engine moving even a quarter-inch, so his mate checked that the big reversing lever was in mid-gear, the hand-brake screwed hard on and the cylinder draincocks wide open.

After about forty-five minutes, the engine had been oiled all round, injector tested, sand-boxes topped up, smoke box door tightened, ashes swept off the front framing, footsteps and footplate cleaned and the tender coal ‘trimmed’: this term means that the coal is broken up with the coal pick into fist-sized pieces, the ideal dimension for effective combustion in the firebox.

The two men stowed their food bags and drinks before checking all their equipment – spare gauge glass, red flags, detonators,14 bucket, coal pick, pricker and firing shovels. Two shovels were always carried in case of accidental loss, either into the firebox or overboard, by slipping from the fireman’s hands; this could easily happen on a rough piece of road. An engine could get along without a lot of things but certainly wouldn’t go far without a shovel to stoke the fire. The second shovel had an unofficial use, for when nature called, enginemen would disappear into the dubious privacy of the tender with it!

With No 224 nicely on the boil, Mitchell, pleased as usual with Marshall’s careful preparation of the fire, took the locomotive off-shed to join the train of carriages waiting at Dundee Tay Bridge station.

Backing down gently onto the six carriages, the engine’s wheels squealed in protest against the sharp curves of the points as the flanges bit into the bullhead rail. Mitchell opened and shut the regulator in a series of short ‘blips’, keeping the engine just moving at about 3mph. He eased up No 224’s tender buffers to those of the leading carriage, so that they kissed gently with a solid double clunk. At the instant of contact, the regulator was opened and the steam brake applied at the same moment. This had the effect of compressing the buffers and catching the engine hard up against the train, making it easier to ‘hook on’.

Marshall hopped off the footplate and got down onto the track to hoist the heavy grease-laden screw coupling on No 224’s tender buffer-beam over the front carriage hook and then to wrestle together the fat black Westinghouse brake hoses.

Even at this hour of the morning, there were at least twenty passengers waiting to board the train. Most of them were making day trips to Fife or Edinburgh to visit kith and kin. The paucity of the Sunday service had enforced this early start but at least it gave them more time to spend with their friends and relatives on their only day off.

Some, like Robert Syme and William Threlfell, were travelling right through to Edinburgh. Twenty-two-year-old Robert, a clerk at The Royal Hotel, Nethergate, was visiting his father Adam. Robert was wearing a dark grey suit and a felt hat and carried a travelling bag initialled ‘RS’. William was 18 years old. He was a thin young man with fair hair and wore a black corded shooting coat, black doeskin trousers and a white shirt. Employed as a confectioner’s apprentice, he lived in Union Street with his mother and was making the trip to see his brother Andrew, a trooper in the Inniskillen Dragoons, whose barracks were at Edinburgh Castle.

Travelling together, David Cunningham and John Fowlis weren’t going far at all, only to St Fort, the first station after crossing the Tay Bridge. The name St Fort was actually a corruption of the old words ‘sann forde’, meaning sandy ford and indeed the area abounded in sand pits and shallow crossings of Motray Water.

David and John had been firm friends since childhood. They were now both 21 years old, both stonemasons and shared the same lodgings at 23 Pitalpin Street, Lochee. They did most things in life together and indeed they were both due to start work building the new asylum at Lochee. They’d decided to spend the day visiting their parents who both lived near Newport on the south bank of the Tay and so bought their nine-penny green third-class return tickets for the 7.30. Robert wore a felt hat, a muffler and a pair of gloves against the sharp December air and, apart from 19s 1d in cash, had his pipe, two books and a number of letters from his sweetheart. He was 5ft 10in tall and inclined to stoutness. David, at 5ft 9in, was also on the plump side and wore a silver watch with a leather ‘albert’ strap, scarf pins and had 11s and a ha’penny in money. Their close association ironically continued after death when they were buried together at Kilmany, Fife.

Also going to St Fort was 25-year-old mechanic George Johnston, 5ft 6in tall with fair hair and wearing light tweed trousers and a blue topcoat. He was paying a visit to his father, a keeper on the St Fort estate at Sandford. However, he was also looking forward to the return journey that coming night because he’d arranged to meet his sweetheart, Eliza Smart, on the evening ‘Edinburgh’ when it arrived there at 7.08 p.m. She was going to be travelling from Cupar, where she worked nearby at Kilmaron Castle as Lady Baxter’s housemaid.