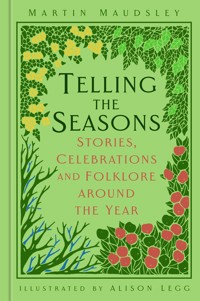

13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Telling the Seasons takes us on a journey through the twelve months of the year with stories, customs and celebrations. Drawing on the changing patterns of nature and the rich tapestry of folklore from the British Isles, it is a colourful guide into how and why we continue to celebrate the seasons. Here are magical myths of the sun and moon, earthy tales of walking stones and talking trees and lively legends of the spirits of each season. Original drawings, sayings, songs, recipes and rhymes, combine into a 'spell-book' of the seasons. Martin Maudsley tells tales around the year to children and adults, specialising in stories of the natural world and local landscapes. He can be found leading seasonal celebrations from firelit winter wassails to bright May Day mornings in rural Dorset where he lives.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

For Ruth,the one who makes the fun happen.

Special thanks to Matthew Pennington for the recipes in this book.

First published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Martin Maudsley, 2022

The right of Martin Maudsley to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 8039 9216 7

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Foreword by Adrian Cooper, Executive Director of Common Ground

Acknowledgements

Introduction: The Wheel of the Year

1 January

2 February

3 March

4 April

5 May

6 June

7 July

8 August

9 September

10 October

11 November

12 December

A Note on Songs

Sources

Common Ground

Matthew Pennington, The Ethicurean

Foreword

The seasons are part of all of our lives, our language and our culture. Seasonality is experienced in all places, rural and urban alike, binding us to nature and the passing of time. As a nation we have been fascinated with measuring and predicting daily and seasonal change, with sundials, weather kites, barometers and tide bells all invented to help people navigate daily life and foretell what the skies and tides will bring tomorrow. The seasons are part of us, embedded in the joy we feel when spring comes or the blues we feel in midwinter. Our culture and language are bristling with music, art, poems, sayings, metaphors and stories, all binding our feelings and thoughts to nature and the seasons. Red sky at night, clear moon frost soon. We can feel ‘right as rain’, have ‘sunny dispositions’ or feel ‘foggy’ in the morning. Some of us are ‘night owls’, some may prefer to ‘wake with the lark’, some are glad to be ‘mad as a March hare’.

Our deep relationship with nature and the cycle of the seasons has long been celebrated by communities in every corner of the country. May Day, Plough Sunday, Michaelmas, Lady Day, Twelfth Night; these were so important that they were fixtures in the cultural calendar, expressing a community’s reliance on nature and a need to celebrate together. Today, it may seem as if only a few of these seasonal celebrations have survived – Halloween, Christmas – but barely discernible under their commercial gloss. But beneath the surface of mainstream culture, in the nooks and cracks, there is a growing resurgence in communal celebration, a bursting of expression that resists the general trends of homogenisation in twenty-first century life. We may no longer be bound by harvest and husbandry to the cycle of the seasons, yet thankfully we cannot stop ourselves noticing the shifting seasons, telling our friends and neighbours about seeing the first snowdrops or bluebells, sharing news of the first returning swift or swallow. This need to share what we notice, to celebrate place and the passage of time, is deep-rooted. And stories have always been our most primal and essential way of sharing our experiences of the world. From parent to child, across communities, from one generation to the next, seasonal stories travel around and become important landmarks in an anxious, changing world.

For several years, Martin Maudsley has been a storyteller-in-residence for Common Ground, helping us demonstrate – from Dorset and Devon, to Manchester and Yorkshire – how seasonality can inspire new attitudes to understanding, while celebrating locality. In these pages, as he weaves old stories with new times, you’ll find the most sumptuous and beautiful gleanings of his rich life as an ecological storyteller, and enjoy each tale as it resonates through time and place. But don’t just keep them to yourself. These story-gifts are generous, and always have been. They do not belong to any one person or community. They are not fixed to a particular place. They are dynamic, borrowed, adapted, passed on. They are an offering for you to share too. Take them into your home, into your school or community, and use them to revive old celebrations or start new ones. Why not start an annual Apple Day celebration, a cake month, bluebell picnics, a full-moon walking club or a society of swift-nest mappers? Because celebrating your local wildlife and landscapes is the root of meaningful conservation, and bringing people together strengthens community resilience and cohesion through uncertain times.

Adrian Cooper, Executive Director of Common Ground

Acknowledgements

The process of gathering ideas and stories for Telling the Seasons stretches back over a period of twenty years as a professional storyteller, with many fellow storytellers (more than I can mention individually) kindly contributing along the way. A particular thank you to word-weaver Jane Flood, whose gentle wisdom infuses both her own storytelling and our long-standing friendship. I’m grateful also to Kevan Manwaring who took the time to read through and comment on the manuscript. A special mention also to Ian Siddons Heginworth, whose wonderful book – Environmental Therapy and the Tree of Life – has been a creative inspiration and constant companion in my own reflective journeys through the cycle of the seasons.

Tom Munro and his team at Dorset AONB provided many opportunities (and welcome financial support!) for storytelling projects and seasonal events that have helped to shape my thinking about the book’s content. I’m also grateful to Darren Moore at the Woodman Inn – a proper community pub – for hosting regular spoken word and folk music events that celebrate the seasons, including outings of Bridport Mummers’ Society (who are always well ‘paid’ in liquid assets). Jon Woolcot and Gracie Cooper from Little Toller Books kindly offered useful insights into the business of writing, during shared Tuesdays working in their fantastic little bookshop in Beaminster. I’m especially grateful to Adrian Cooper, editor at Little Toller and executive director of Common Ground, for reading early drafts, contributing the book’s foreword and all his generous advice and encouragement in writing about seasonal celebrations over the years. In my role as storyteller-in-residence at Common Ground, I’m pleased, and proud, to have been part of a long-term project in Manchester with Jane Doyle and Freya Morton, telling and recording stories around the wheel of the year. Many of the seasonal folk tales in the book were first told within a Forest School setting, with a wonderfully ‘wild’ group of children from St Mary’s Levenshulme RC Primary.

I’m extremely grateful for the hard work and artistic talent of Alison Legg in creating the wealth of original drawings within the text. It’s not an easy task to capture the essence of the written content, but her illustrations of plants, animals and cultural traditions are beautifully sensitive to the seasonal shifts in time. Similarly, Matthew Pennington has gone well beyond the bounds of duty in creating original recipes for each month. Drawing on both his passion for cooking and deep knowledge of wild food, he has generously spent many hours researching, testing and tasting, for which I am deeply indebted.

The main writing period of the book coincided with the Covid-19 pandemic and several lockdowns – not to mention periods of ‘writer’s block’. For helping to keep my head above the water in tricky times, I’m deeply grateful to my family and Bridport friends, including Dickie, Nick and Nathan, plus all the denizens of ‘Sadness Copse’. Most of all, my partner Ruth Mackay provided epic levels of support and legendary amounts of patience during the whole writing period. Also, huge hugs to my two amazing children Orran and Annie, who have listened to me telling stories many times. I’ve relished all our wild adventures through the seasons as a family – here’s to many more!

Introduction

The Wheel of the Year

‘There’s time … and there’s time,’ as storyteller Hugh Lupton once said. ‘Time that travels forward in a straight line, and time that travels round in circles.’*

This book is about circular time: the cycle of the seasons around the wheel of the year. It draws on folk tales and folklore, celebrations and customs, that together hold our shared experiences and cultural expressions of the turning seasons. Although many such traditions stretch back in time, accrued over past generations, they continue to offer insights and inspiration for us to connect with the recurring rhythms of nature. Our innate desire to gather together socially is also fulfilled through the auspices of the seasons: from midwinter feasts to midsummer fires; from May Day to Apple Day. Seasonal celebrations help us to navigate the year, through personal connections and communal interactions, engendering a deep-rooted sense of both time and place. There are many powerful reasons why we’re impelled to celebrate the seasons, but I’m reminded of a fable in fellow storyteller Peter Stevenson’s book, Welsh Folk Tales, briefly retold in my own words:

One springing morning a skylark rose up on her ladder of song above a little orchard where an old pig was tied to a tree. The boar looked up with small, squinting eyes and grunted loudly at the frivolous bird: ‘Why do you fly so high and sing so loudly, when no-one gives a fig for your song?’ The skylark replied: ‘I sing because it’s spring and the sun is shining, and because unlike you I’m not tethered to a tree.’

The Wheel of The Year

The word calendar derives from the Latin verb calare, meaning to ‘call out’, in reference to vocal acknowledgement of seeing the new moon each month from Roman times. Like skylarks, we have been merrily singing the seasons and calling out auspicious times of year since the dawn of humanity. The custom calendar in Britain and Ireland therefore comprises a rich mix of many cultural influences; underpinned by physical factors such as astronomy, climate and geography. In structuring the monthly chapters of this book, I have highlighted three main spokes in the festive wheel of the year: the stations of the sun as marked in the old Celtic calendar; the evocative Anglo-Saxon namings for months and full moons; and the parade of annual saints’ feast days through the Christian church’s liturgical year. Some prominent Roman rituals and festivals are also included, especially where they help illuminate the origins of familiar seasonal customs.

The Silver Apples of the Moon,the Golden Apples of the Sun

I talk with the moon, said the owl

While she lingers over my tree,

I talk with the moon, said the owl

And the night belongs to me.

I talk with the sun, said the wren

As soon as he starts to shine,

I talk with the sun, said the wren

And the day is mine.

In the Northern Hemisphere, the solar year is intrinsically divided into four equal quarters by the seasonal summits of winter and summer solstices (when daylight is at its lowest and highest) and the midpoints of spring and autumn equinoxes (when day and night are equal length). The specific dates vary slightly from year to year, but fall around the twenty-first day of the month in December, March, June and September, in succession. In the pre-Christian Celtic calendar, the year was sub-divided into eighths through four additional celebrations that herald the inception of each season: Imbolc (1st February) for spring, Beltane (1st May) for summer, Lammas (1st August) for autumn and Samhain for winter (1st November). The festivities generally began the night before, with the lighting of flames outdoors, and are often referred to as the four fire festivals, or sometimes as cross-quarter days. These moments of seasonal transition were particularly luminous, and numinous, in our ancestral past: ripe with superstition and in rich myths and legends, that continue to reverberate into modern times.

These markers might seem slightly out of phase with conventional meteorological definitions of the four seasons. However, they chime in tune with much of the farming traditions and seasonal folklore of Britain and Ireland, as well as with natural cycles. For example: there are many visible stirrings in the wild world by the beginning of February, from flowers to frogspawn, long before many people would declare for spring in mid-March. Alongside Celtic festivals based on the solar year, the Anglo-Saxon lunar almanac offers many descriptive insights into how we have adapted culturally and agriculturally to the seasons. Their traditional names for monthly full moons are particularly resonant, such as the widely recognised Harvest Moon, occurring closest to the autumn equinox in September. Others are less familiar now, such as Milk Moon in May or Hay Moon in July, but are equally vivid as seasonal descriptors in the climate and landscapes of these islands. It should be noted that the named full moons can vary slightly in which month they fall, due to discrepancies between lunar and solar cycles – they are realigned each year at spring and autumn equinoxes. There are also many Old English or Germanic names for the calendar months themselves that help highlight connections between people, place and time of year. These are often quite matter-of-fact and relatable in modern times, as in the designation of ‘mud month’ for February!

When the Saints go Marching in

The church calendar comprises a rich tapestry of high days and holidays that once offered many other occasions for social interactions and seasonal merry making through the year, particularly in medieval England. Some of the festivals of Christian saints were adopted and assimilated from earlier, pagan celebrations (e.g. Imbolc developing into St Brigid’s Day). Others simply gathered their own folk traditions over time (e.g. Michaelmas), helping to add resonance and relevance for those living in close connection to the land and the seasons. The original interpretation of the Latin paganus simply referred to a ‘country dweller’, so it’s likely that some Christian rituals were gradually ‘paganised’ through the everyday practices of rural people. With one or two exceptions, such as St Valentine’s Day perhaps, few of the saints’ days are widely or loudly celebrated anymore. However, they continue to provide meaningful markers through the year for folklore, food and festivities; and perhaps are ripe for renewal. The Church calendar also prescribed the four ‘quarter days’ that evenly divide the year, and once held huge importance in regulating agricultural practices, commercial arrangements and seasonal fairs. In England these were: Lady Day (25th March), Midsummer’s Day (23rd June), Michaelmas Day (29th September) and Christmas Day (25th December). Again, these dates are clearly closely aligned with older seasonal celebrations of the solstices and equinoxes.

Keeping Up with Tradition

Tradition is not the worship of ashes but keeping the flames alive.

Gustav Mahler

In many ways, this book is a collection of traditions: traditional tales, customs and celebrations. But use of the adjective ‘traditional’ should not be taken as being synonymous with old-fashioned, out-dated or behind the times. From its Latin roots, the word ‘tradition’ comprises two elements: trans (meaning ‘across’) and dare (meaning ‘to give’). Thus, its intended meaning could be expressed as ‘to give across’ or ‘hand over’. Tradition, therefore, refers to a mode of transmission: the passing on of stories, skills, information or ideas, by word of mouth, from person to person, across generations. As well as carrying an inherent sense of generosity, it’s also open-ended. Traditions survive, or are revived, because they still carry meaning and are valued within communities where they take place. Although rooted in history, many of the seasonal celebrations and customs highlighted within this book can be seen as living traditions, rather than traditional beliefs.

The prefix ‘trans-’ also relates to ‘change’, and there’s an implicit understanding that as traditions are passed on, they are free to change in the hands of the next person. There’s no compulsion to do things exactly as they’ve always been, yet they provide a helpful, familiar framework to start from, before weaving in new strands and associations. Traditional music sometimes shares the same sentiments, as folk singer Chris Wood once commented, ‘Tradition should be respected, convention should be broken.’ As well as being progressive, traditional customs are often highly non-conformist, subverting the norms of conventional living and breaking the routines of everyday life. What could be more radical than climbing a hill in the dark on a May morning to greet the sun, or standing in a cold orchard to toast the naked apple trees in January? Such seasonal traditions are inherently wild and playful in nature; but a glass of ale or drop of cider always seem to help participants revel in the occasion.

Well-Seasoned Stories

The question we should ask of myth is not is it true or false, but whether it carries meaning in our time.

R. Holloway, quoted in Richard Mabey’s The Cabaret of Plants

It’s unsurprising, given our long-standing and dependent relationship with the changing seasons, that they are deeply woven within the stories we’ve told each other over time. Folk tales, and folklore, offer both a window into past intimacies and also an abiding means of making sense of the world around us, with all its shifting seasonal subtleties. Each chapter of this book, from January to December, begins with a ‘framing’ story to set the seasonal scene for that particular month. These are retellings of traditional tales, mostly British and Irish; many of which I’ve told in person at seasonal events through the year. A few more folk tales are scattered through the pages to illustrate and illuminate the magic and mystery of each monthly moment. I’ve included one or two myths from other northern European countries that hold specific, unique symbolism of the seasons (e.g. Dawn and Dusk, an Estonian folk tale retold in June).

Folk tales often have their seasonal significance in terms of indicative plants and animals, from precocious snowdrops to springing hares and summer moths to autumn foxes. Several of the seasonal stories feature ‘shape-shifting’: the supernatural ability for humans to transform into animals or trees, and vice versa – perhaps highlighting our close relationship, biologically and culturally, with the rest of the natural world. Therefore, each chapter includes a few salient references to wild sightings and sounds for that month; that help us to ‘tell the season’. Geographical location clearly plays an important role in seasonal phenomena, such as the arrival of migrant birds and the timing of wild harvests. I freely, and happily, admit that my own observations and perceptions are biased towards south-west England, where I have lived and worked for many years. Within each chapter there are also several well-observed and finely drawn illustrations by Dorset artist Alison Legg. Like flowers pressed between the pages, they complement the stories and help conjure the imagery of the natural world through the changing seasons.

The capriciousness of nature, as well as the boom or bust nature of living from the land, are often vividly brought to life through traditional tales about the fairy folk. They are quick to anger and fickle in their affections, yet capable of unexpected and unbridled acts of generosity. Such ‘fairy tales’ seem to flourish at specific, seasonally sensitive times of year, in particular the start of summer (May), harvest time (August) and the onset of winter (November). Stories of the Good Neighbours remind us to keep, or restore, the covenant of customs between ourselves and the unseen forces that regulate the natural world. Several stories also feature examples of ‘folk magic’ – repeated rituals that make sense of, and hopefully mitigate, the unpredictability of the seasons and the vagaries of the weather (and/or the fairies). Perhaps, the underlying principles in such practices still ring true: being grateful for what we’ve got, satisfied with enough and remaining hopeful for the future.

A Taste of the Seasons

There’s nothing quite like food, glorious food for creating a sense of festivity and marking a moment in the cycle of the seasons. As well as a liberal sprinkling of food-related folklore throughout the book, there is also a bespoke recipe for each month – created by Matthew Pennington, owner/chef at the Ethicurean restaurant in Wrington, near Bristol. I’ve been lucky to work alongside the restaurant for many years at festive events, notably their annual winter wassail – a wild and well-fed affair. Around the year, they produce changing menus of fresh, local, seasonal, ethical, and above all delicious, food. No one pays more attention to when, where and how food is sourced and served. Under the heading of Flavour of the Month, Matthew offers twelve food and drink ideas; each tailored to the ingredients and inspiration of the season. The recipes are miniature stories in themselves; weaving together culinary traditions, foraged flavours and innovative techniques.

Old Roots, New Shoots

This book is not a comprehensive compendium of the whole calendar of British and Irish festivities – a gloriously bountiful and wide-ranging topic, and covered by a great many other volumes. Instead, the focus here is on celebrations and traditions that directly relate to aspects of seasonal phenomena in the outdoor world, both wild and cultivated. Also, as a storyteller, I have been drawn to celebrations with a strong narrative element, either in their origins or how they relate to existing myths and legends.

Since 2015 I’ve been storyteller-in-residence at Common Ground, a groundbreaking environmental arts charity based in Dorset. For many years, they have been at the forefront of championing both natural diversity and local distinctiveness through shared cultural expression. In the 1990s, under the inspired leadership of Sue Clifford and Angela King, Common Ground successfully established two brand new seasonal celebrations in the UK: Apple Day (in October) and Tree Dressing Day (in December). In doing this they incorporated wide-ranging traditions and current environmental concerns, whilst bringing new vigour to the festive calendar. Since then, there has been a conspicuous surge in the prevalence and popularity of revived or reinvented seasonal celebrations, from blossom festivals to winter wassails, and many others around the year. These locally expressed festivities foster tangible connections between people, place and time of year; whilst avoiding overtly religious, commercial or political affiliations.

Fuelled by this spirit of revival, and drawing on the ethos and innovation of Common Ground, the potential for recreating further seasonal celebrations are ripe and rife. Crucially these could, and should, feature a diverse range of seasonal highlights that resonate most strongly within different local communities. For instance: celebrating the return of swifts in late spring; revelling in the floweriness of a local hay meadow in high summer; and savouring the fruits or changing leaves of a local, landmark tree in autumn. It’s also an opportunity to draw deep from the well of local history, initiating an annual occasion for telling the tales of positive parochial characters that have helped to shape the nature of the local area. At the end of each chapter there is a short section, ‘Old Roots, New Shoots’, exploring some of these ideas, drawing freely on the cultural traditions and natural wonders of each month, with suggestions for new expressions. Hopefully, some scattered seeds will find fertile ground, widening and diversifying our calendar of seasonal celebrations yet further in years to come.

Changing Times

In the UK, and most of the western world, the year is chronologically organised according to the Gregorian calendar. The previous system, the Julian Calendar, failed to accurately account for the orbit of the Earth around the sun, and over time was slowly slipping out of phase. Many Catholic countries on the European continent were early adopters of the calendrical shift, but Britain didn’t accept the substitution until the Calendar (New Style) Act of 1750. The actual change took place in 1752: when 2nd September was followed by 14th September, overnight (losing 11 days). Although it was made law to adhere to the revised dates, the new style calendar was greeted with both confusion and resentment of time-honoured traditions being desecrated by the authorities. To this day, several seasonal celebrations still follow the Old Calendar – such as Old Twelfth Night for wassailing.

Such slips in time may have caused an uproar in their day, but on the whole annual celebrations more or less kept in touch with the seasons. More recent, man-made climatic shifts, however, are causing much more widespread, disruptive and worrying effects. The changing seasons themselves are now in a state of flux. Most notable in Britain and Ireland, perhaps, is the increasingly early arrival of spring. Phenology – the scientific study of natural phenomena – has documented a whole string of precocious arrivals, openings and behaviours. Recent evidence suggests that many spring ‘events’ now happen a whole month earlier than they did just forty years ago.

Sadly, and ironically, there are now several seasonal festivities that have become dislocated from their underlying cause for celebration: for instance, Cuckoo Fairs in April often take place without an appearance of their star attraction. On the other hand, continuing to intentionally mark the passing of the seasons through the year allows opportunity to regularly (re)connect with the natural world around us. Witnessing changes for ourselves, first-hand and in our own particular patch, can be the first step in caring, and then sharing, about what is happening in the wider wild world. What’s more, allowing ourselves to pay attention to circular, perennial time can engender a sense of reciprocity and self-restraint – the need to give back, in order to take out. Similarly, many traditional tales hold both stark warnings of the consequences of breaking natural constraints but also the redemptive possibilities of emotional and practical change. Finally, there is much inherent joyfulness in being an active part of local seasonal celebrations – it invigorates the spirit and defies despondency. ‘There’s a worse crime than crass destruction, and that’s crass despair,’ wrote Simon Barnes in How to be a Bad Birdwatcher. Celebrating the cycle of the seasons around the wheel of the year, outdoors and in good company, is the best antidote to despair of which I know.

Martin MaudsleyCandlemas, 2022

____________________________________

* Paraphrased from Christmas Champions, a musical storytelling show with folk singer Chris Wood about mummers’ plays. Hearing it was a personal inspiration in terms of both story-telling and seasonal celebrations.

1

January

We know by the moon we are not too soon,

We know by the sky we are not too high,

We know by the stars we are not too far,

We know by the ground that we are within sound.

The Twelve Months

Once there was a girl called Mary, who lived in a cottage at the edge of a forest. As she grew up, she brought great joy to both her parents: bright as spring, soft as summer and honest as autumn. But, one cold, cruel winter, her mother became ill and quickly died. Not long after, her father married again; believing his daughter needed a feminine presence at home. However, his new wife arrived with her own daughter and barely concealed contempt towards Mary. Whilst her father was working in the woods, the stepmother forced Mary to do all the housework, as well as feeding the chickens and milking the cow. The days were long and hard for Mary but, being sweet natured, she did all that was demanded of her, without mentioning anything to her father.

One January day, as cold northerly winds brought heavy falls of snow, her father had to go into town for a week. Poor Mary was left alone with her stepmother and stepsister, who gleefully saw an opportunity to be rid of Mary for once and all.

The next morning the stepmother came into the kitchen and said, ‘Mary, go into the forest and pick primroses. I want to see their bright yellow petals shining in my daughter’s hair.’

‘How could I do such a thing?’ replied Mary. ‘Primroses don’t grow in the snow!’

‘Do as I say, or your father will hear how horrible and rude you are!’

Unwilling to disappoint her father, Mary wrapped her thin woollen shawl around her shoulders and stepped outside into the cold. She had no idea where to go, so headed north into the white, winter weather. She walked until the snow slid down her boots, numbing her toes, and her face was pinched with icy cold. Eventually, she came to the forest and there, between the bare birches, was a flickering fire. Edging closer, she saw a circle of twelve men and women sitting round the fire; all different ages and all dressed differently. On the highest seat was an old woman wrapped in a wolf-skin cloak with flowing, snowy-white hair and skin as fair as frost. Her eyes glinted bright blue in the firelight. Mary was utterly amazed by what she saw, but feeling suddenly colder, she stepped forward and politely addressed the old woman: ‘Grandmother, please may I warm myself by your fire?’

The old crone smiled at Mary and beckoned her to come closer. ‘My name is Mother January. These are my brothers and sisters: together we are the Twelve Months. But what brings you to these woods on a cold winter’s day?’

Mary told her story, explaining that she needed to somehow find primroses to take back to her stepmother. Old Mother January shook her head sadly, but then stood up and walked over to one of the men in the circle. He was much younger than her – as slender as a willow sapling, with smooth skin and bright, green eyes. ‘Brother March, please take my place for a while,’ she said.

March swapped positions with Mother January. With his own ash wood wand, he started to stir the flames, which blazed bright green. Immediately, the snow melted, the birch trees burst into leaf and the ground was carpeted with pale yellow primroses beneath the trees. ‘Pick them quickly!’ said March, his voice lilting like birdsong.

As quickly as she could, Mary gathered a posy of primroses then, thanking Mother January and Brother March, she scampered home as fast as she could across the snow. When she opened the door, her stepsister and stepmother looked up with undisguised surprise – they’d assumed she was already frozen death in the snow. But they took the flowers to arrange in their hair, and ordered Mary to get on with her chores.

Early next morning, as Mary was laying the fire, the stepmother came into the kitchen and said, ‘Mary, we’ve decided that we want something sweet to eat for breakfast. Go and bring back ripe strawberries from the forest.’

‘What? Strawberries don’t grow in the snow!’

But the stepmother angrily grabbed Mary by the arm and pushed her out of the door, before she’d even had chance to put on her shawl. At least Mary knew the way: she walked through the snow and into the forest of birch trees, until she saw the flickering fire. Old Mother January was once more sitting at the head of the Circle of Seasons, stirring the flames. Mary stepped forward and bowed respectfully as she told of her task to find strawberries. Mother January smiled kindly, then approached the woman sitting exactly opposite her in the circle. ‘Sister June, please take my place for a while.’

Sister June was wearing a leafy gown of many different shades of green with a wreath of roses crowning her lustrous, golden hair. She readily swapped places with January, then began to stir the fire with an oaken wand. Instantly the flames leapt higher; yellow and orange, as bright as the sun itself. The snow suddenly melted and the trees were green again; small birds singing in their branches. Mary watched in wonder as underneath the trees, green plants with white blossoms started to produce ripe, red berries. ‘Pick them quickly!’ said June, warmly.

Mary picked the strawberries, popping a few in her mouth, but soon filling her wicker basket. Thanking both Mother January and Sister June, she ran home swiftly, still savouring the flavour of the strawberries. Her stepmother and stepsister were even more surprised to see Mary back this time – although their dismay soon turned to delight when they tasted the juicy strawberries, which they gobbled greedily until their chins were stained red.

Having enjoyed the sweet strawberries, the very next day the stepmother demanded Mary go back into the forest to bring a basket of ripe apples. Wearily, Mary left the house and set out into the cold. Once more she walked, through snow and forest, to the clearing where the Twelve Months were sitting round their fire. Mother January welcomed Mary. Then, after hearing of her new plight, addressed one of the older men in the circle. ‘Brother October, please take my place for a while.’

October was hale and hearty, dressed in brown deer-skins, his russet-red beard flecked with grey. He swapped seats with Mother January and stirred the fire with his apple wood wand, turning the flames a deep, crimson red. The snow melted away and the birch trees were again covered with leaves; not green but gold. Among the birches stood a solitary apple tree, its shiny red fruit hanging heavy on brown-leaved branches.

‘Shake the tree!’ said Brother October with a bristly grin. Willingly, Mary shook the tree and gathered the apples as they fell gently to the ground. She thanked Mother January and Brother October and ran home across the snow. This time the stepsister and the stepmother were waiting. They snatched the basket of apples and began to eat them immediately, biting through the thin skin and savouring the juicy flesh within. They’d never tasted anything so delicious and desirable in all their life. They looked at each other with greed glinting in their eyes.

‘If this miserable wretch can find winter fruits, just think what we could fetch from the forest. We’ll bring back bright treasures to live a life of luxury and leave Mary and her pathetic father to their own poverty.’

Wearing thick, fur coats and warm, leather boots, they set out into the wintry weather, following Mary’s footsteps through the snow and into the wild woods. There they wandered around for a while, getting colder and angrier, until eventually they found the clearing with the Twelve Months sitting around the fire. Without asking permission, they rudely burst into the circle to warm themselves in front of its flames.

‘What are you looking for?’ asked Mother January, her blue eyes flashing.

‘Give us diamonds and pearls, old hag!’ they shouted, rudely.

Then Old Mother January shook her snowy white hair and began to stir the fire vigorously with her rowan wand – the flames turning bright blue. An icy wind blew through the trees and a flurry of fat snowflakes began to fall; as thickly as feathers shaken from a pillow. By the time Mother January’s cold snowstorm had finished, the stepmother and stepsister were frozen solid where they stood – their still-open eyes shining like diamonds and their icy skin as pale as pearls.

A few days later, Mary’s beloved father came back. He hugged his daughter warmly then listened, with both sadness and astonishment, to the cold tale she told. Mary never saw the Twelve Months again, although she often thought of them sitting round their fire in the forest. She loved all the changing seasons, but her favourite time of the year was January; the first and oldest of all the months.

Out with the Old, in with the New

The Old Year now away is fled,

The New Year now is entered …