5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

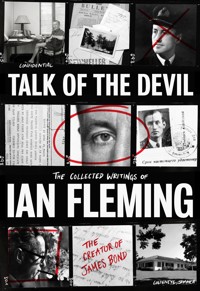

- Herausgeber: Ian Fleming Publications

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

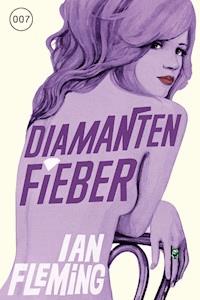

'One day in April 1957 I had just answered a letter from an expert in unarmed combat writing from a cover address in Mexico City, and I was thanking a fan in Chile, when my telephone rang…'The Diamond Smugglers is the true story of an operation responsible for smuggling millions of pounds worth of precious gems out of Africa. Ian Fleming, creator of James Bond, drew on interviews with the reluctant hero of the diamond companies' counter-attack to explore the world of the real master criminals of his time.The result rivals Fleming's greatest spy novels.An essential piece of reporting, written in Ian Fleming's own clear and vivid prose. Rediscover this incredible piece of historical writing.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 164

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

The Diamond Smugglers

The Diamond Smugglers

IAN FLEMING

Contents

Preface

1: The Million-Carat Network

2: The Gem Beach

3: The Diamond Detectives

4: The Safe House

5: Enter Mr Orford

6: The Million-Pound Gamble

7: Senator Witherspoon’s Diamond Mine

8: The Heart of the Matter

9: Monsieur Diamant

Postscript

Preface

The fishing and game-watching holiday in the St Lucia estuary of Zululand was something I had been looking forward to for a very long time. I had just locked the front door of my house in Johannesburg and was getting into the car for the 450-mile drive to the coast when a grey uniformed postman pedalled up with a telegram. I felt a strong temptation to leave the thing unopened, but luckily thought better of it and found it was from Ian Fleming. Fleming’s cryptic message was to lead to one of the pleasantest episodes I have had in a varied career and, what was more important, it involved no interference with my trip to Zululand. Fleming merely wished to know what time and where he could contact me by telephone within the next few days. I cabled back ‘St Lucia Hotel Zululand any evening’ and, hardly expecting to hear any more, off I drove with my fishing-rods.

I did, in fact, hear quite a lot more, and after a spate of telegrams between London, St Lucia and Tangier my meeting with Fleming took place just as he describes. On arrival at the El Minzah Hotel, Tangier, I was greeted by the porter with a note which I still have (alas, I have been taught to keep even the most trivial notes!):

‘Welcome! I’m in Room 52. Would you give me a ring when you arrive and we’ll have a drink. Good to have you here.’

IAN F.

This seemed a promising beginning and I was not to be disappointed. Fleming’s company during the next ten days or so was a stimulating experience.

One of the things I liked about him was his informality. He was known to quite a few members of the British community in Tangier and he automatically included me in the various luncheon and dinner parties they gave for him.

This is where my ‘cover’ came in, and now is my opportunity to offer an apology for my part in the deception practised on a lot of charming people who were much too well-bred to ask awkward questions at the time.

Polite formalities at the Minzah soon gave way to down-to-earth discussion about the form and scope of this book.

I made it plain from the start that, although the decision to tell the story was taken entirely on my own authority, I wanted to be sure that the published version would be free from security and all other objections. Ian Fleming, as a former naval intelligence officer, entirely agreed and, as things turned out, had to tone down a few of my rather critical opinions, and some interesting names and details had to be withheld altogether. It was my desire that the story would offend no one but the crooks; and that, I think, has been achieved. To some extent Fleming was helped by the fact that I had brought with me a private diary of my own activities which I had been compiling in idle moments over a long period, and it was these notes and my memories which he has most skilfully forged into a connected narrative.

This bizarre meeting in Tangier had its origins in November 1953, when Sir Percy Sillitoe had retired as head of MI5. He told me when he asked me to join him how it had all come about. He was enjoying his leisure at Eastbourne when a letter arrived from Sir Reginald Leeper, the former British Ambassador, and then, as now, Chairman of the London Committee of De Beers Consolidated Mines.

Sir Ernest Oppenheimer had asked him, as he put it, to see if Sir Percy would be interested in giving his advice and assistance on a matter which he hoped to have an opportunity of putting before Sir Percy.

‘The matter’ turned out to be the enormous illicit traffic in diamonds, and Sir Ernest Oppenheimer’s desire that Sir Percy should set up an organisation to combat it.

Who would not have been interested? Sir Percy at once flew out to Muizenburg, just outside Capetown, where Sir Ernest was spending his summer holiday.

Sir Percy was immensely struck by Sir Ernest Oppenheimer – by his charm and by his razor-sharp mind – and he couldn’t understand why his biography had never been written: the story of the man who started in Kimberley in 1902 as the representative of a small diamond firm and who, in less than fifty years, built up the largest combined diamond, gold, coal and copper empire in the world.

It seems that Sir Ernest was indulgent about Sir Percy’s total ignorance of the diamond industry up to the moment when diamonds get set into engagement rings. He explained the basic process of mining and marketing diamonds and the points at which, in his opinion, there were possibilities of leakage. He then suggested that Sir Percy should make a personal examination of the mines themselves all over the African Continent and return to Johannesburg and report on the prospects of plugging the leaks at least at the producing end of the business.

Sir Percy agreed and, in March 1954, set off with two of the team he had by that time selected, on an itinerary which in six weeks included Accra, Aquatia, Freetown, Yengema, Leopoldville, Tshaikapa, Bakwanga, Luluabourg, Dundo, Elizabethville, Lushoto, Dar-es-Salaam, Mwadui, Lusaka, Salisbury, Pretoria and Johannesburg – a journey I am astonished that, at the age of sixty-six, he managed to complete without collapsing by the wayside.

Unfortunately there had already been leakage to the Press, and Sir Percy thought it advisable to call on his old friend Mr Swart, Minister of Justice, and also Major-General J. A. Brink, the Commissioner of the South African Police, and tell them in confidence of his assignment. He gave them his assurance that in no circumstances would he employ an agent or informer for use in South Africa without the consent of the Commissioner of Police. He also endeavoured to meet Brigadier Rademeyer, then head of the CED. It was he who had set up the Diamond Detectives branch of the South African Police with headquarters at Kimberley. As ill luck would have it he was on holiday at that time, and it came as an unwelcome blow to Sir Percy to read in one of the South African newspapers that Brigadier Rademeyer was very critical of his proposed and alleged activities and had commented adversely on the fact that he had not paid him a visit. But I must say that later, when IDSO (we called ourselves the International Diamond Security Organization) was in full operation, all of us found Brigadier Rademeyer most co-operative and helpful, particularly when he had succeeded Major-General Brink as Commissioner of Police.

In his six weeks’ tour of the diamond mines Sir Percy told me that he was dazzled by the thousands upon thousands of diamonds, from pea to walnut in size, which were laid out for his inspection at the different mines, and he began to absorb some of the sinister fascination which has always surrounded these coldest of all gems. Objects so small and at the same time so valuable were obviously destined for ever to have crime, and even murder, attached to them and, having seen the way they were handled up to the moment when they were posted to London for sale by the Diamond Corporation, Sir Percy said he was only surprised that the annual leakage by theft, smuggling and illicit digging did not add up to many more millions than the figures which had been given him. Not only Sir Percy but all of us acquired real admiration for the various company officials through whose hands pass every day gems worth perhaps a hundred times their annual salary.

Sir Percy’s plans were approved and he flew back to London and took me on to complete his team, and that was how, three years later, I came to meet Ian Fleming in Tangier. I treated my time in Tangier rather like the reward of a chocolate after swallowing a dose of medicine. The main difference was that Tangier was unexpected. Working for the International Diamond Security Organization was not ‘fun’. The only ‘prize’ was the satisfaction of Sir Percy Sillitoe – a man who is not easily satisfied, but who, from time to time, sent us signals of encouragement as we set about our main tasks. These were, first, to increase security at the mines and, secondly, to discover beyond doubt the major channels of leakage to Europe, the Middle East and the Iron Curtain countries.

The latter task was the more difficult of the two, but at least we had the advantage of being able to adopt one method of attack – buying from the smugglers themselves – which was not available to the police forces owing to lack of money. Our undercover buying in Liberia and Rhodesia was not expected to lead directly to convictions, but it did result in the penetration and exposure of whole networks of smuggling rings which had hitherto been hidden.

The normal police system of attacking the IDB [Illicit Diamond Buying] problem had in the past largely relied on the ‘trap’ method whereby a selected suspect is approached by a plain clothes policeman and invited to buy ‘police’ diamonds. At the critical moment, when the suspect falls for the policeman’s offer, he is arrested. The operation is concluded without gleaning a single item of genuine intelligence.

The persistent operation of the trap method no doubt served the useful purpose of preventing IDB from establishing the upper hand in countries like South Africa, but the police inevitably came in for severe criticism from the Bench after instituting proceedings based on a trap. Thus, in the High Court of South-West Africa in September 1953, Mr Justice Claasens, in finding a father and son named Vlok not guilty of IDB, said there were two kinds of trap. One was for those suspected of dealing in diamonds and the other was to induce innocent people to do what they normally would not do. This case, he pronounced, was of the latter type, with the additional aggravation that the decoy was a relation of the accused. ‘These cases,’ said the Judge, ‘come close to the prostitution of the police and of the Courts.’ We in IDSO agreed with this view and thought very little of trapping of any sort.

During its short life, IDSO’s relations with most police forces, particularly those of British Colonial territories and protectorates in Africa, were extremely happy. Most of these forces had more serious problems on their hands than IDB, but of those plagued by the latter, Sierra Leone had easily the worst of it. The Commissioner of Police, Bill Syer, and the head of the CID, Bernard Nealon, could not have been more co-operative and, from Sir Percy down, we were deeply grateful for their attitude.

As we have lately seen, the situation in that unfortunate territory is still far from good, though many of IDSO’s recommendations for improving security have been gradually implemented. The permission granted by the Sierra Leone government to the Diamond Corporation to set up diamond buying posts in the vast diamondiferous areas of swamp and jungle in the interior has completely altered the legal and commercial basis of diamond mining and dealing. The basic issue now resolves itself into a straight commercial fight between the Diamond Corporation on the one hand and the IDB on the other. The winner will be whichever side captures the goodwill and output of the thousands of recently legalised African diggers. The IDB have the advantage of being able to fix their prices without taking into account export duty and, in some cases, they are backed by unlimited resources from behind the Iron Curtain. The Diamond Corporation on the other hand has the advantage of official government support, stable prices and, I hope by this time, adequate deterrent measures against smuggling across the Liberian frontier.

Already a very substantial proportion of the illegal traffic has been diverted into the official channels provided by the Diamond Corporation, but the commercial battle is not likely to be decided within a month or a year.

Ian Fleming describes how the Diamond Corporation of Sierra Leone, under the chairmanship of Philip Oppenheimer, has set about its task with tremendous energy and enthusiasm. The Government of Sierra Leone is equally determined to clear out – and keep out – the illegal immigrants from neighbouring French territory who are battening on Sierra Leone. Similarly the thousands of Syrian and European dealers who have acted as middlemen in the past will be obliged to jump off the fence between legality and illegality if they wish to continue either living in or visiting Sierra Leone. The Governor of Sierra Leone recently stated that one dealer alone had sold diamonds to the value of £80,000 to the Diamond Corporation and to the value of £240,000 to the illegal dealers. This man is notorious and it is a pity that his name, like many others, must for the time being be suppressed.

I will end with two general comments on this book.

First, Ian Fleming has adopted the convenient literary device of making one individual, myself, the chief and omniscient operator for IDSO, but I should make it quite clear that the IDSO was a team whose success, such as it was, should be credited to Sir Percy Sillitoe and to the Organization as a whole.

Secondly, I would be the first to admit that our work was by no means completed. Today there are still dotted round the world powerful criminals living beneath a cloak of sunny respectability in an affluence which still comes from diamonds smuggled out of Africa.

These men will hear of this book and they will read it, out of fear or vanity, to see if their activities have been revealed or their names are mentioned.

A word of warning to these far from gentle readers. It is most unlikely that the name of any one of them was not on the files of IDSO in London or Johannesburg; and, though IDSO itself has been disbanded, ‘international diamond security’ is not a transient organisation, but a permanent function of the police and the Customs men.

‘JOHN BLAIZE’

1

The Million-Carat Network

If you write spy thrillers you are apt to have an interesting postbag. One day in April 1957 I had just answered a letter from an expert in unarmed combat writing from a cover address in Mexico City, and I was thanking a fan in Chile, when my telephone rang.

It was a friend. He sounded mysterious. ‘You remember that job Sillitoe was on? Well, it’s just finished and his chief operator says he’ll now tell you what it was all about. He’s amused by your books, particularly that diamond-smuggling one. He thinks you’d be able to write his story. He’s ready to tell you everything within reason – names, dates, places. I’ve heard some of it and it’s terrific. But you’d have to meet him in Africa – Tangier probably. Can you get away?’

I knew something about Sir Percy Sillitoe ’s job. When he retired as head of MI5, De Beers had hired him to break the diamond-smuggling racket. Paragraphs about his goings and comings had leaked into the papers from time to time over the last few years. It seemed that the racket had been losing the Diamond Corporation stones worth more than ten million pounds a year. If this unnamed spy would really talk it would obviously be worth sacrificing my Easter holiday. I asked one or two questions. Would these revelations be made with the blessing of De Beers?

They would not. In that case, were there any security objections to the story being told? My friend was of the opinion that there weren’t. I said I would go.

My friend gave me the man’s name – John Blaize – which was one of his aliases, and a telephone number, improbably enough in Zululand.

There followed a week of meetings – with an informative friend from Scotland Yard; in my club with a mild little man from Antwerp – and a flurry of cables with Blaize of Zululand. I had tried telephoning him, but was told that he was out trying to photograph a white rhinoceros – another touch of the bizarre. Then I took off by Air France to the Hotel El Minzah in Tangier, to wait until, on the thirteenth of the month, John Blaize would contact me.

I had found out what I could about Blaize – public school and Oxford, Bar examinations and then into the office of the Treasury Solicitor. When war came he joined up as a private in a county regiment, but after his commission he was posted to Military Intelligence, where he had done extremely well and ended up as a lieutenant-colonel. After the war he was tempted into MI5 and had been one of the team which eventually broke the Fuchs case. He had then concentrated on penetrating the Communist underground – an unsavoury and sometimes dangerous job which had taken him round the world. In 1954, Sir Percy Sillitoe, one of whose gifts is knowing really good men, enticed him away with a glittering salary to help on the diamond operation.

After that, for three years, Blaize had gone to earth in Africa, whence his activities had sounded echoes in Beirut, Tangier, Antwerp, Paris, Berlin and even Moscow.

Now the job was done, the main leaks plugged, the final arrests made, and Blaize was on his way out of the shadows and back into the light of day.

Blaize duly turned up on time, and we met in my bedroom at the Minzah.

He was a man of about forty, dressed in the typical uniform of the Englishman abroad – Lovat tweed coat, grey flannel trousers, a dark blue rope-knit sweater, nondescript tie, and rather surprisingly, a fine white silk shirt of which he later confessed he owned twenty-four. He had inconspicuous but attractive good looks. He had dark hair flecked with grey, and shrewd, humorous, slate-coloured eyes that turned up slightly at the corners. His smile was warm and his voice quiet with a hint of hesitation. He spoke always with a diffident authority, and whenever I interrupted he would carefully turn over what I had said before replying.

When he was consulting his notes, he was a don or a scientist – head thrust forward, shoulders a little stooped and sensitive, quiet hands leafing through his scraps of paper, but when he crossed the room he looked like a cricketer going out to bat: gay, confident, adventurous.

He was a typical example of the English ‘reluctant hero’, and I got to like him enormously.

He was tired when he arrived – with a tiredness that came from more than his journey; and shy. He was also rather nervous about being spotted in Tangier, and during the week we worked together he insisted on our meeting at odd places and at odd times. Then he would unburden himself of his story, verifying dates and facts from untidy scraps of paper.

When he had finished I would get the story down and he would later correct what I had written. It was desperately hard work, but we enjoyed it.