Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

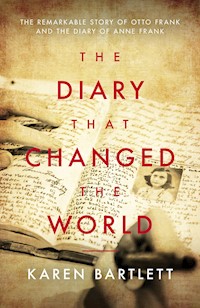

"A meticulous account of the fascinating, convoluted and sometimes ugly publishing history of the world's most famous diary. Karen Bartlett's book is all the more relevant at a time of untruths and fake news." – Caroline Moorehead, bestselling author of Village of Secrets: Defying the Nazis in Vichy France *** When Otto Frank unwrapped his daughter's diary with trembling hands and began to read the first pages, he discovered a side to Anne that was as much a revelation to him as it would be to the rest of the world. Little did Otto know he was about to create an icon recognised the world over for her bravery, sometimes brutal teenage honesty and determination to see beauty even where its light was most hidden. Nor did he realise that publication would spark a bitter battle that would embroil him in years of legal contest and eventually drive him to a nervous breakdown and a new life in Switzerland. Today, more than seventy-five years after Anne's death, the diary is at the centre of a multi-million-pound industry, with competing foundations, cultural critics and former friends and relatives fighting for the right to control it. In this insightful and wide-ranging account, Karen Bartlett tells the full story of The Diary of Anne Frank, the highly controversial part it played in twentieth-century history, and its fundamental role in shaping our understanding of the Holocaust. At the same time, she sheds new light on the life and character of Otto Frank, the complex, driven and deeply human figure who lived in the shadows of the terrible events that robbed him of his family, while he painstakingly crafted and controlled his daughter's story.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 432

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

v

For my father

vi

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

‘I identified with her situation, and therefore the lessons of that tragedy sunk more deeply in our souls and encouraged us. If a young girl of thirteen could take such militant actions then so could we…’

Nelson Mandela, on readingThe Diary of Anne Frank in prison

When Otto Frank unwrapped his daughter’s diary with trembling hands and began to read the first pages, he was discovering a side to ‘his Anne’ that was as much a revelation to him as it would be to the rest of the world. It was late 1945, and in Amsterdam life was bleak: Europe had been torn apart by war; the city was recovering from a brutal Nazi occupation and years of famine and hardship. The few returning Jewish refugees straggled back to an unwelcoming country that had once been their home. For many the fate of their families was unknown. In unwrapping the package before him Otto must have felt he was handling a miracle – opening a portal to the past that offered the chance to reconnect with his lost life, and the people he had loved. x

Otto read the first words and was quickly overcome with emotion. He did not know that he would take the bundle of handwritten pages before him and turn his daughter into an icon, placing a teenaged girl with dark hair, a fiendish temper and a lopsided smile at the heart of a debate about twentieth-century history – with themes about growing up, persecution, human values and religion still as contested today.

As a man who had survived Auschwitz only to discover that his entire family had perished, Otto Frank must have believed he had already experienced the worst that life could hold. Undoubtedly that must be true, but he had many painful struggles ahead. Little did he know that his desire to share his daughter’s story with the world would spark a bitter battle over the nature of the diary and Anne’s legacy that would embroil him in years of legal battles, driving him to a nervous breakdown and eventually into a new life in Switzerland.

Since Otto Frank arranged the first publication of The Diary of Anne Frank in 1947, it has sold more than 31 million copies and been translated into seventy languages. There have been five different editions of The Diary of Anne Frank, two graphic biographies, five books for children, seven feature-length documentaries, one BBC TV series and three feature films. An animated film, Where Is Anne Frank by Israeli director Ari Folman, debuted at the Cannes Film Festival in 2021, while books like Nathan Englander’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank continue the debate about Anne’s legacy. In Amsterdam, 1.2 million people visit the Anne Frank House every year to see the secret annexe where the diary was written, while more than a million people in the UK have seen the touring Anne Frank exhibit. To those who weary of her singular fame, xiit sometimes seems like everyone who ever met Anne Frank has written about their acquaintance, however fleeting.

Anne’s journey through adolescence, set against the backdrop of the Holocaust, quickly became an iconic text of the twentieth century, as widely read and resonant in Japan and Cambodia as in the US, Germany and the UK. Upon its publication, thousands of young people wrote to Otto to express how much the book reflected their own teenage years, while world leaders, including Nelson Mandela, who read the book during his incarceration on Robben Island, sought inspiration from Anne’s message of hope and humanity.

This remarkable impact was driven by the determination of one man: Otto Frank. Once an ordinary loving father of two girls, Otto became the guardian of Anne’s memory – overseeing every aspect of the diary’s publication and its legacy to the point of obsession. From its inception, The Diary of Anne Frank would test Otto to his limits.

Hard as it now seems to believe, from the very first reading people opposed the publication of the diary. In Amsterdam the influential Rabbi Hammelburg called Otto ‘sentimental and weak’ and said all ‘thinking Jews in the Netherlands’ should oppose the ‘commercial hullabaloo’ of the diary and the Anne Frank House. Later, in 1997, Cynthia Ozick of the New York Times said, ‘The diary has been bowdlerized, distorted, transmuted, reduced; it has been infantilized, Americanized, sentimentalized, falsified, kitschified, and, in fact, blatantly denied…’ Criticism of how the diary was interpreted could be harsh and emotional – and sometimes justified.

Yet Anne’s story touched a chord. Within three years the diary had been translated into several languages, with critics commenting xiion the ‘mixture of danger and domesticity that has a particular poignancy…’ Undoubtedly it was the publication of the diary in the US that would catapult the story of Anne Frank to worldwide fame, but this also marked the beginning of Otto’s relationship with a supporter who would turn into a nemesis. Meyer Levin was an American writer who would go on to fight Otto over control of Anne’s legacy in a series of bitter court battles and engage public figures on his behalf, including even Eleanor Roosevelt.

While Otto fought in the US courts to preserve his control of the diary and its dramatic rights, he was also forced to defend its authenticity in Germany, where Holocaust deniers brought a series of claims against him alleging that the diary was a fake that Otto had written himself. The Diary of Anne Frank was now at the heart of the battle over Holocaust denial, and controversy would rage for decades, exacerbated by the revelation in the 1980s that Otto had personally withheld five pages from publication. An unexpurgated publication of the diary in the 1990s prompted another round of soul-searching over Otto’s editing of the original script.

One young girl’s diary had touched millions of lives. Over the years thousands of readers wrote to Otto, seeing him as a father figure in their own lives and taking up long correspondences with him, which he meticulously answered sitting in his study in Switzerland, day after day. In Germany young people founded Anne Frank clubs and there was even an Anne Frank Village for refugees. In Japan the diary became a runaway bestseller, offering a chance to discuss a war which was largely taboo. The diary broke other taboos in Japan too – young girls read it as it was one of the first books to speak about menstruation, and soon girls began to talk about having their ‘Anne Frank’. xiii

Anne Frank and the diary meant many different things to many people – none of which Otto could have envisaged in 1947. By the time Otto died in 1980 he had become symbolic of one view of the Holocaust, and humanity, which downplayed – in some people’s eyes – the full horrors that the Jewish people had suffered, the diary ending as it did before Anne’s capture and death in Bergen-Belsen.

Otto, the saintly father figure, was as sanitised as Anne had become herself. The reality was more complicated, and more compelling. Otto lived many lives, enjoying a privileged childhood at the pinnacle of German society only to lose everything in the 1930s and restart his life almost as a door-to-door salesman in Amsterdam. He strove above all to protect his family but was powerless to prevent their horrible deaths at the hands of the Nazis. Returning to Amsterdam as a shattered man, he was gripped by the absolute conviction that his daughter’s handwritten diary had a message for the whole world. He was a loving, sensitive and traumatised man who found happiness again with his second wife but was at the same time often overwhelmed with nervous exhaustion and fits of deep depression. He was driven by an obsession with Anne and Anne’s legacy that overrode all else, and arguably blotted out even the memory of his other daughter Margot.

Today, almost eighty years after Anne’s death, that battle to define what she means to the world is still intense, with the future of a multi-million-pound industry at stake as competing foundations, cultural critics and former friends and relatives clash over the legacy of Anne Frank – and who should control it.

This book goes beyond conventional biographies of the Frank family to examine the story of The Diary of Anne Frank, the xivhighly controversial role it played in twentieth-century history and publishing and the fundamental role it has played in our understanding of the Holocaust. Moreover, this book will examine the way in which the diary holds a mirror to the second half of the twentieth century and how the ongoing conversation about its role and authenticity still has relevance to our discussions about religion; the rise in antisemitism; gender; culture and cultural appropriation; bias in the writing of history; the commodification of tragedy; and suspicion regarding corporate charitable fundraising. At the same time, the book will shed new light on the life and character of Otto Frank, the complex, driven and deeply human man who lived in the shadows of the terrible events that robbed him of his family while he painstakingly crafted and controlled his daughter’s story.

In the end, it’s arguable that, for Otto, his mission to spread awareness of Anne’s diary was, if anything, too successful. His work resulted in an unstoppable momentum and appetite for her story, and her worldwide popularity has often rendered her an abstract symbol for a variety of individuals and interest groups. That may be its greatest weakness – or the source of its strength and enduring power. At the heart of The Diary of Anne Frank is the relationship between Anne and Otto, who together crafted a story that has been ceaselessly reimagined by successive generations of readers. All this makes it simultaneously one of the best-loved and most controversial – and certainly one of the most potent – books ever published. One young girl’s diary changed the world.

CHAPTER 1

‘QUITE CONSCIOUSLY GERMAN’

BASEL, DECEMBER 2014

The Christmas decorations and markets light up Basel, making this small Swiss city on the borders of both France and Germany seem uncommonly cosy and cheerful. Like many people in their seventies and eighties, two Basel residents, Buddy Elias and his wife Gertie, are downsizing – clearing out the attic and getting rid of several generations’ worth of papers, clutter and possessions from their family home. Unlike most other pensioners, however, Elias is Anne Frank’s cousin and one of the last living relatives who remembers her. The papers and artefacts are not family trivia, meaningful only to a few close relatives and destined for the dustbin, but an extensive testament to the Franks and the Eliases. They are a remarkable and rare history of a German Jewish family that will be part of a permanent exhibition at the new Frank Family Center, housed at the Jewish Museum of Frankfurt. Researchers from the centre have been staying with Elias and his wife for a week, sorting through final 2possessions, and now the removal trucks have arrived to take the archive north into Germany. ‘When the chair goes, I will be sad,’ Elias says, referring to a small chair that Anne used to sit on when she visited him as a girl on holiday. ‘I was a lively boy, Anne was a lively girl and her sister Margot was a reader. I had a jack-in-the-box theatre at home, with a grandmother that popped out and a crocodile. I’d play it for her, and she loved that.’

Elias lived a double life for decades: on the one hand a successful German-speaking actor who made his name as an ice-dancing clown in Holiday on Ice; on the other president of the Anne Frank Foundation in Switzerland, where he fought numerous battles over the years to make sure his cousin’s work was not exploited. The rehousing of the artefacts will turn out to be one of Buddy Elias’s last acts as the keeper of the family flame – reminding the world that the Franks were once a proud German family. ‘Amsterdam was an asylum for Anne and her family for eleven years during the Nazi time. But it cannot be regarded as their home. Now the artefacts have to go back to the place where the Frank family lived since the seventeenth century; that’s Frankfurt.’

Buddy’s uncle was Otto Frank. Tall, dashing and witty, Otto was, as his daughter Anne described him in her diary, ‘extremely well brought up’. Radiating charm and kindness and drawing on an ample supply of money, he was perfectly well-placed to enjoy the life of a wealthy young man in the early years of the twentieth century. For upper-class Europeans, these were halcyon days – before wars, financial crises and social uprisings would irreparably alter their way of life. The Frank family were happily settled in a large suburban villa in Frankfurt, where Otto and 3his brothers and sister came of age, spending their days engaged in rounds of tea parties, dancing, horse riding and becoming embroiled in blossoming – and then failed – romances. Otto’s life was particularly gilded in that it included university study in Heidelberg and the glamour of a first job with Macy’s department store in New York City. The fact he crossed the Atlantic several times by ocean liner, something no ordinary German could have dreamed of, was testament to the family’s wealth and position. For young Otto, the future looked promising, and the present was great fun.

Otto’s father, Michael Frank, had left his hometown of Landau in 1879 at the age of twenty-eight and settled in Frankfurt. Seven years later he married 21-year-old Alice Stern, a member of a well-known and prosperous family, and moved into stockbroking and banking, as well as investing in various businesses, including two health farms and a company that made cough lozenges. The Franks’ first child Robert was born in 1886, followed by Otto on 12 May 1889, Herbert in 1891 and Helene (known as Leni) in 1893. In 1901, Michael Frank founded the Frank bank, specialising in foreign currency exchange, and then moved his wife and children into their family home – a large semi-detached villa at 4 Mertonstrasse with long balconies and landscaped gardens.

The Franks fitted into their place in the upper echelon of German society perfectly. Except for one thing, of course: they were Jewish. Frankfurt had long been a centre of Jewish life in Germany and was the home of great banking dynasties like the Rothschilds. Yet Germany in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was rife with antisemitism, as nationalist groups employed vile rhetoric and lies to try to force Jews from 4every area of public life. Jews were increasingly viewed as a race rather than a religious group, and in Germany antisemitism was flavoured with what historians like Daniel Goldhagen argue was a distinctly ‘eliminationist’ character that was entrenched in German culture. Between 1899 and 1939, Germany passed 195 laws, or acts of discrimination, against Jewish people, while Great Britain passed eight and France one.

If this encroached on Otto Frank’s otherwise enjoyable life it was, at first, only dimly. ‘There was at this time some anti-semitism in certain circles, but it was not aggressive and one did not suffer from it,’ Otto remembered. Like many families in their economic strata, the Franks considered themselves German first, Jewish second, and Otto pointed out that he would not have become an officer in the First World War if he had not felt ‘quite consciously German’. Later he admitted this had made no difference in the eyes of his persecutors.

Firmly non-religious, Otto did not have a bar mitzvah or learn Hebrew. While the family valued Jewish traditions, they ate pork and ignored religious holidays. His family, he later wrote, never set foot in a synagogue.

As a boy, Otto first attended a private prep school and then the local Lessing Gymnasium, where he was a popular student. His cousin remembered him as ‘outgoing and fun and he became an accomplished cellist, enjoyed writing for the school newspaper, and developed a love of classical German literature’. Although he was the only Jewish student in his form at Lessing, this fact would not become important to him until much later in his life – when he angrily replied to a classmate who had written a book about their time at the school, stating, ‘I was unpleasantly struck by your apparently knowing nothing about the 5concentration camps and gas chambers, since there is no mention of my Jewish comrades dying in the gas chambers.’ Otto reminded him he was the only member of his family to survive the horrors of the Holocaust.

At the time, however, Otto was only concerned with seeking out new and stimulating experiences. Bored with parties and balls, waltzing and dinners, a trip to Spain in 1907 sparked what would be a lifelong passion for foreign travel, and, after passing his Abitur in 1908, he left again for a long trip to England.

When he returned to Germany, Otto enrolled for a short spell studying economics at Heidelberg University, where he met and became close friends with Charles Webster Straus, a young American on a year abroad from Princeton. Although Otto left Heidelberg after only a couple of terms, his friend Charlie invited him to the United States for a year’s work experience at Macy’s department store, where his father was part-owner. Straus Senior assured Otto that if he enjoyed the job, a good career at Macy’s awaited him. By this time Otto had already embarked on a training programme with a bank in Frankfurt and was engaged to be married – but he seized the new opportunity, sailing for New York in September 1909 on the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse. On board, Otto spent the long and rainy voyage enjoying the magnificently appointed accommodation and writing letters to his sister Leni to celebrate her sixteenth birthday. After only a few days in New York, however, his dream was shattered when he received news that his father was dead.

Michael Frank had died suddenly of a heart attack on 17 September 1909. He had said what turned out to be a final goodbye to his son Otto on the docks in Hamburg only a few weeks earlier. When Otto returned to Germany his carefree 6youth was over: Alice Frank had taken control of the bank, but without Michael the future of the family business seemed uncertain – and Otto’s fiancée had spectacularly broken off their engagement.

Otto had been romancing a girl before his departure for New York and asked her to wait for him. She did not. According to Otto’s cousin Milly Stanfield, he took the break-up of his youthful love affair ‘very hard’, and he withheld the references Anne made to his first failed love affair in the published edition of the diary. ‘It can’t be easy for a loving wife to know that she’ll never be first in her husband’s affections, and Mummy did know that…’ Anne had speculated. Whether his disappointment really did stretch over decades is unknown (a later account by Stanfield suggested that it did not), but certainly by Christmas 1909, a dejected Otto returned to New York in very different circumstances to resume his work at Macy’s.

Otto stayed in New York, off and on, for two years, socialising for the first time with other wealthy Jewish families, learning the ropes of working for a big department store, attending charity balls and immersing himself in local politics, when Charlie announced his decision to run for office. Eventually, though, he returned to Germany for good. In 1911, Otto took up a position with a metal engineering company in Düsseldorf and appeared to pick up his old life as it had been, with lavish lunches, trips to the circus, visits to his mother and family holidays in Switzerland. Milly Stanfield described a visit to the Franks after Otto’s return where they held ‘a big luncheon with an enormous ice-cream gateau decorated with fairy-tale figures, and Tanti Toni invited us all to the circus’. Despite outward appearances, though, the world was changing. When Milly returned on 7her next holiday from London in July 1914, she found the house convulsed in near hysteria at the prospect of the outbreak of war, and the French branch of the Frank family, Otto’s Uncle Leon, Aunt Nanette and their sons Oscar, Georges and Jean-Michel, described the extreme antisemitism they suffered in Paris. By August, Milly and her family were advised by the British Consulate to return to England, and they departed from a chaotic Frankfurt train station feeling that a wall of fire now separated Germany from the Allies.

Like many young men on both sides, Otto entered the war with energy, excitement and the optimism of certain victory. Although German military academies had previously made it very difficult for Jews to enrol, the advent of the First World War meant that 100,000 Jewish men would be drafted into battle. After a year on loan to a company doing war work, Otto joined the army in August 1915 and wrote a cheerful letter to his family from the training depot in Mainz. ‘All in all I think I’ve got it good,’ he noted. Adding that the food was ‘pretty good’ and that he’d had to clean the windows and polish his boots, he concluded that he’d rarely spent a more amusing train journey than the one to the training depot. Some of the officers drank like fish, but he was quite content, even if not looking forward to the prospect of sleeping on a straw bed. He summed up: ‘Everyone wants to join in the victory!’

In 1916, Otto was sent to the Western Front, where he was attached to the infantry as a range finder and survived the Battle of the Somme before being promoted to lieutenant in 1917. Throughout the war he would continue to write thoughtful letters to his family back home, usually offering advice on daily matters to his little sister and rarely, if ever, describing the 8horrors he witnessed. In June 1918 he told Leni he was in a good mood, sitting in fine weather looking at some roses – longing for the ‘easy life’ to start again.

As a surviving soldier from the Western Front, Otto understood perhaps more than anyone that, in truth, the ‘easy life’ had vanished for ever. He returned to the family home on Mertonstrasse in January 1919 to face his worried family, who had been expecting him weeks earlier. After listening to Otto’s explanation that he had been honouring his word and returning two horses to a farmer in Belgium, Alice Frank flew into a temper and threw a teapot at his head. Life for the family had been far from easy in their years apart. The French part of the family had been decimated when Uncle Leon committed suicide by jumping out of a window after the deaths of his sons Oscar and Georges in the war. Aunt Nanette had been committed to a mental hospital – leaving only the one remaining son, Jean-Michel, behind. In Frankfurt the family bank was in severe trouble after Alice’s investment in war bonds wiped out a large part of their wealth. Faced with such dire circumstances, Otto reluctantly took over running the bank and the family cough-lozenge business. For several turbulent years he steered the business, navigating the plummeting German mark, political instability, growing extremism and rising antisemitism.

In the early 1920s, Otto attempted to set up a foreign currency trading arm of the bank in Amsterdam, but when the attempt failed he returned to Frankfurt in 1925 and, to the astonishment of his wider family and friends, promptly announced his engagement to the unknown Edith Holländer, a young woman from a wealthy Jewish family in Aachen. At the relatively advanced age of thirty-six, Otto was finally getting the family he 9had told his sister he craved, but equally importantly, he would benefit from a large dowry that he hoped would help save the family business.

Otto had spent a romantic youth, but his marriage, which took place in Aachen on 12 May 1925, his thirty-sixth birthday, was a ‘business arrangement’. Later he would admit that he had not been in love with his first wife, but they settled down together into a comfortable and secure union. The Holländers were a more religious family than the Franks and had founded their family fortune on a scrap-metal empire. On the eve of her marriage, at twenty-five years old Edith was described as shy, family-orientated and academic – yet she also had a wide circle of friends, played tennis, cut her hair in a stylish 1920s bob and danced the Charleston. While Anne was often tempted to muse over her father’s passionless imprisonment – ‘What kind of marriage has it turned out to be? No quarrels or differences of opinion – but hardly an ideal marriage. Daddy respects Mummy and loves her, but not with the kind of love I envision for a marriage … Daddy’s not in love’ – Otto himself was more sanguine. He wrote to Edith on their wedding anniversary in 1939 that while they had been buffeted by the whims of fate, ‘the most difficult situations haven’t disrupted the harmony between us’. Commending Edith for her spirit and solidarity, Otto added, ‘What is still to come nobody knows, but that we will not make life miserable for each other through little arguments and fights, that we do know. May the coming years of our marriage be as harmonious as the previous ones.’

After a honeymoon in San Remo in Italy, Otto and Edith returned to live in Frankfurt. At first they lived in the family home in Mertonstrasse, with Otto’s mother, his sister Leni, now 10married to Erich Elias, and her family, including her second child Buddy. On 16 February, Otto and Edith’s first daughter, Margot Betti, was born, and one year later the family took the unusual step of moving out of the family home and into their own large apartment on Marbachweg, which they rented from landlord Otto Konitzer, a Nazi Party supporter. Cementing their happiness, their second daughter was born at 7.30 a.m. on 12 June 1929 – Annelies Marie. Writing in Anne’s newly started baby book, Edith says, ‘Mother and Margot visit the baby sister on 14 June. Margot is completely delighted.’

Otto was a loving father to both girls, taking over bathtime and reading them bedtime stories when he returned from work – including one he invented himself called ‘The Two Paulas’, about two sisters, one good and one bad. From the beginning, though, he had a special bond with Anne, who was as wilful and lively as Margot was tranquil. Anne was ‘a little rebel with a will of her own’, Otto said. When she woke through the night it was Otto who would go to her, soothe her and sing to her.

Despite the injection of Holländer money, however, the Frank family bank and business was floundering due to the dire state of the German economy – and the Franks were finding themselves subject to increasingly virulent antisemitism as the Nazi Party rose to power.

In 1929, Otto’s brother-in-law Erich Elias left Frankfurt to open a branch of Opekta in Switzerland. Opekta was part of a company that manufactured pectin, used as a gelling agent in jam, and would play an important role in the Frank family – although Otto did not know it at the time. Leni and son Buddy joined Erich in Basel the following year.

Back in Frankfurt, the Frank family bank and the lozenge 11business had seen an enormous dip in profit due to the Wall Street Crash, and Otto began what would become a familiar round of downsizing – moving both businesses into a smaller, cheaper premises.

To make matters worse, the following year Otto’s brother Herbert was arrested and sent to prison for committing illegal foreign exchange transactions. Their mother Alice was forced to travel to Paris to ask her nephew Jean-Michel to lend her money to keep up mortgage payments on the house in Mertonstrasse. Although she had managed temporarily to keep the wolf from the door, Otto wrote to her and questioned whether it still made sense to hold on to the house ‘from an economic and political point of view’.

The ‘political point of view’ was already impinging more significantly on the life of the Frank family. Otto had been forced to move his family from their spacious home in Marbachweg when his Nazi landlord decided he could no longer ‘stomach’ taking rent money from a Jew. The family had moved into a smaller apartment in Ganghoferstrasse, but in December 1932 they were forced to leave there too due to their dire economic circumstances, and go back to the family home on Mertonstrasse.

Otto understood he was merely playing for time. In July 1932, the Nazi Party (NSDAP) had won 230 seats in the Reichstag, and in January 1933 Otto and Edith were visiting friends when they heard on the radio that Hitler had been made Chancellor. Otto recalled that he looked across at Edith and saw her sitting as if turned to stone, but their host for the evening cheerfully piped up: ‘Well, let’s see what the man can do.’ The Franks were already aware of what he could do. Their former domestic 12servant Kathi Stilgenbauer recalled asking who the ‘Brownshirts’ were in 1929, and while Otto had tried to make light of it, Edith had looked grave and said they would all find out the answer to that soon enough.

By the time Hitler took power, Otto and Edith had heard the stormtroopers marching past singing ‘when Jewish blood spatters off the knife’, and they were already discussing how to leave Germany. Yes, the scale of it was daunting, and Otto had already tried and failed to set up a business in Amsterdam in the 1920s. But a new law decreeing forced segregation in schools made the Franks determined to leave. Margot’s teachers had been dismissed in favour of Nazi Party officials, and she was forced to sit apart from her non-Jewish classmates. Still, for Otto the question remained: how would he be able to support himself and his family if they went away and gave up more or less everything?

Otto turned to Erich Elias for help, and Erich suggested that he set up an independent branch of Opekta in Amsterdam, financed by an interest-free loan of fl. 15,000 repayable over five years. Otto accepted and the family prepared to leave Germany, with Otto travelling directly to the Netherlands while Edith and the girls stayed in Aachen until they could find a suitable home in Amsterdam. It was an enormous and emotional decision. ‘My family had lived in Germany for centuries,’ Otto recalled. ‘We had many friends and acquaintances but by and by many of the latter deserted us, incited by the National Socialist propaganda.’

Otto took his last photo of his family in Germany in March 1933, using his trusty Leica camera. In the picture, Edith and the children look serious, clutching each other’s hands as they stand in Hauptwache Square in central Frankfurt. Three weeks later, on 1 April, the Nazis incited a nationwide boycott of Jewish 13businesses and began to pass a series of laws banning Jews from most parts of business and social life.

By August, Otto and his family had left Frankfurt, the city of Otto’s happy childhood and family life, and embarked on a precarious journey into the unknown. Otto wrote that when the people of his country had turned into nationalist hordes and cruel antisemites, his world had collapsed. He had to face the consequences, and though it hurt him deeply he realised that Germany was not ‘the world’ – and he left for ever.

For the first few months in Amsterdam, Otto rented a room and travelled to his small Opekta office by tram. During the autumn of 1933 Edith visited him often as they looked for a family home together – finally settling on a modern, light, three-bedroom apartment at 37 Merwedeplein in the Rivierenbuurt, where many other Jewish immigrants were settling. The Franks rented the apartment in December 1933, and by February 1934 both Margot and Anne had joined them. ‘One must not lose courage,’ Edith Frank wrote to Gertrud Naumann a few days after her arrival, for, unlike her husband and children, Edith was desperately homesick for Germany, lamenting the poorer quality of Dutch clothes, her smaller home, the superiority of German sweets and the hard-to-learn Dutch language. While Otto, Margot and Anne had the advantage of quick assimilation into Dutch culture through work and school and soon began speaking equal parts Dutch and German to each other, Edith struggled through unsuccessful Dutch lessons with a neighbour and began to lean more on her religion – paying weekly visits to the liberal synagogue.

The Franks were only four of the more than 25,000 German Jewish immigrants to enter the Netherlands between 1933 and 141938, and their arrival prompted often hostile and prejudiced reactions. Speaking German on the streets was discouraged. ‘It was not about antisemitism then. There was a lot of anger and dislike towards us because we were German. It didn’t matter that we were Jewish Germans arriving in the country for fear of our lives; we were simply Germans to the Dutch,’ recalled Laureen Nussbaum, whose parents had known the Franks in Frankfurt before emigrating to the Rivierenbuurt in 1936. Nor were the immigrants always greeted warmly by the existing Dutch Jewish community, who often resented their more affluent homes and lifestyles. In the 1930s the Dutch authorities strongly pressured new arrivals to move on to a third country and be resettled elsewhere through the Committee for Jewish Refugees.

By 1939 the number of Jewish people in the Netherlands had grown to 140,000, 60 per cent of whom lived in Amsterdam. In that same year the Dutch government began constructing a large refugee camp, Westerbork, which was later to play a crucial role in the deportment of Jews to Nazi concentration camps.

Despite Edith’s homesickness and an undercurrent of anti-German sentiment and antisemitism in Amsterdam, for a few years at least the Franks settled into a happy family existence. Still, it was certainly not the life they had been used to in Germany; Otto travelled constantly to grow his business, but it remained unprofitable until the 1940s, and for many years he relied on family loans. Friends reported that he often looked tired and exhausted. Edith worried about the looming Nazi threat on the border and urged Otto to consider emigrating to somewhere safer, but he did not want to. There were personal tensions too. In 1935 and 1936, Otto employed a Dutch woman, Jetje Jansen, as a tester at Opekta, and her husband Joseph to build display 15stands for trade exhibitions. In the course of their employment Joseph became convinced Otto and Jetje were having an affair, which sparked a deep hatred towards Otto that lasted for years. The couple divorced, Joseph joined the Dutch SS following the Nazi invasion, and his grudge towards Otto has been suggested, in an unproven claim, as a possible reason for the family’s betrayal in 1944. Whatever the truth, it would not be the last time Otto’s friendship with a woman led to unhappiness.

For the children, at least, life was less complicated. More families arrived in Merwedeplein, and the Franks made new friends and adopted a cat. Anne and Margot went on holiday to Basel, where their grandmother Alice now lived with Aunt Leni and cousins Stephan and Buddy, learning to ice skate in the winter and spending summer afternoons running around in mountain pastures. Edith’s mother, Rosa, also visited from Aachen, and Edith took the girls into the city for visits to shops and museums. Margot was clever at school and wanted to grow up to be a nurse in Palestine. Anne, by contrast, hated mathematics and only worked at the subjects that interested her. ‘Anne was a normal, lively child who needed much tenderness and attention and who delighted us and frequently upset us. When she entered a room, there was always a fuss,’ Otto recalled. ‘Margot was the bright one. Everybody admired her. She got along with everybody … She was a wonderful person.’

Visiting relatives and friends remembered the sense of warmth in the family. Writing home, Anne and Margot’s cousin Stephan reported that he slept very well in his fold-up bed, and that Anne would sit and chat with him at 6 o’clock every morning before Otto woke up and joined them and Margot jumped down from the top bunk. Anne’s best friend, Hanneli Goslar, 16said Otto was ‘a wonderful father’ and remembered that he would sit with them every night, drinking a beer and tipping the glass up and up, and they would sit open-mouthed waiting for him to spill it – but he never did.

At work Otto had been joined by new employees, some of whom would become family friends and an important part of the Frank family story – most notably Miep Gies, who herself had emigrated to the Netherlands from Austria as a child in 1920. Miep and her husband regularly visited the Franks at home, and she remembered how the Opekta employees had stood silently around the radio when the Nazis swept into Austria and Hitler announced the annexation in 1938. For Edith Frank it was an ominous turning point, and she begged Otto to emigrate to America, where other members of the family had settled. Otto, however, took a more optimistic view and regarded Amsterdam as ‘a haven’, expecting that the Netherlands would remain neutral and untouched as it had in the First World War. By the time he was forced to face the truth, it was too late.

On 1 September 1939, Germany invaded Poland and two days later was at war with Britain and France. The Second World War had begun, and the Nazi invasion of Denmark and Norway in April 1940 meant that even the Netherlands could no longer ignore the threat on its borders. Otto’s cousin Milly recalled getting a letter from Otto saying ‘how terribly unhappy he was because he was sure that Germany was going to attack’. While the Franks put on a calm front for their children, they were now frantically working to get out of the country, with Otto using all his old contacts in New York to get immigration papers. His efforts failed. Edith’s brothers Walter and Julius had emigrated to Massachusetts and found work with a box company. After 17growing close to the owner, they got him to agree to sign the necessary papers to bring the Franks to the US, but by the time this had been agreed time was short – and soon the borders had closed. Cousin Milly suggested they might at least send Margot and Anne to live with her in England but, after discussing it, Otto and Edith turned down her offer, saying they could not go through with it. Their daughters meant too much to them, and they could not bear to be parted.

It was a fateful decision. On 10 May 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. During four terrifying days of attacks by paratroopers followed by a bombing raid, thousands of Jewish residents tried every avenue of escape – running down to the harbour when they heard, falsely, that boats there would carry them to England. By 14 May the Dutch royal family, the Prime Minister and his Cabinet had fled to England in exile and the Netherlands had capitulated to German rule. The country was now to be governed by Reich commissioner Arthur Seyss-Inquart, who had formerly ruled the Nazi-annexed Austria and instituted a reign of terror against the Jews there.

For the first few months, however, the Nazis proceeded cautiously, not wanting to alienate the Dutch population, who they believed were naturally ‘Aryan’ and very similar to Germans. Gradually, though, a series of anti-Jewish laws were passed, each more punitive than the last. Jewish companies were required to register, and Dutch citizens were asked to pinpoint Jewish homes on maps. By 1941 Nazi laws prohibited Jews from participating in almost all professions and all areas of social life and entertainment, including going to the beach, the cinema and parks. Jewish children were expelled from their normal schools and sent to special Jewish schools.18

During this time Otto and Edith tried to maintain a normal family life. Otto wrote,

When I think back to the time when a lot of laws were introduced in Holland, due to the occupying power, which made our lives much harder, I have to say that my wife and I did everything in our power to stop the children noticing the trouble we would go to, to make sure this was still a trouble-free time for them.

As ever, he was closest to Anne, choosing to take her away with him for a few days to a hotel in Arnhem, where he could rest and recuperate. Edith held birthday parties for both girls, and they were encouraged to give whatever they could to poor beggars who came to the front door asking for food. At school, Margot continued to study hard, while Anne began to develop crushes on local boys.

Beneath the façade, however, life was becoming intensely difficult for the Franks. At home, Rosa Holländer, who was now living with them, developed cancer and died in 1941 – something Edith and the children found particularly devastating. Under the new laws the entire family was required to register as Jewish with the Nazi authorities, and Otto had been forced to ‘Aryanise’ his businesses, officially signing them over to the ownership of Dutch members of staff while he secretly continued to run them behind the scenes. Otto’s companies were now supplying the German Army with the gelling agent pectin and other goods – but their lives and livelihoods were put under direct threat when Tony Ahlers, a violent antisemite and Nazi collaborator, appeared in Otto’s office on 18 April with a blackmail letter.

The letter Ahlers carried was from Joseph Jansen, who had 19been nursing his hatred of Otto since the suspected affair with his wife years earlier. In it, Jansen claimed that Otto was supplying the German Army but had been heard to say anti-German things in conversation, including that the war would last years and Germany would suffer terribly. Ahlers demanded a payment to stay quiet – which Otto handed over immediately, sealing the start of an ongoing blackmail relationship which would haunt him. Miep Gies recalled that after Ahlers left the office, Otto emerged looking ashen. According to biographer Carol Ann Lee, Miep said,

Mr Frank read me the letter and I remember, still today, that it was written in the letter that the Jew Frank was still tied to his company and had expressed himself in an anti-German fashion during a conversation. I don’t know who signed the letter, but I deduced from the content that it had been written by the Jansen I knew.

Under such pressure it was hardly surprising that Otto was beginning to crack. Writing in her diary on 7 May 1944, Anne recalled, ‘I have never been in such a state as Daddy, who once ran out onto the street with a knife in his hand to end it all.’

It was becoming increasingly clear that the only option for the family was to go into hiding, and hopefully to remain there until the end of the Nazi occupation. It was an eventuality that Otto had been preparing for since 1941, identifying the upstairs annexe of his office at 263 Prinsengracht as the most suitable hiding place, papering out windows and doors and recruiting his trusted staff to begin carrying in supplies of food, plates, cutlery, linen and all that they would need to sustain them.20

On 12 June 1942, Anne celebrated her thirteenth birthday, receiving amongst other gifts a diary from her parents. It was a momentous gift, although no one realised it at the time. During those weeks Otto and Edith began preparing the children for the fact they would soon be leaving their normal lives behind them. On 4 July, Otto wrote to his family in Switzerland that everything was fine, although they knew that day by day life was getting harder. ‘Please don’t be concerned,’ he added, ‘even if you hear little from us.’ In another letter to Julius and Walter, he said he regretted that he would not be able to correspond with the family but was sure they would understand.

The day came on Sunday 5 July, when sixteen-year-old Margot Frank was ordered to report to the SS for deportation to a Nazi labour camp. Thousands of Jewish boys and girls in the Netherlands received a similar order that day, the first in the series of systematic deportations of Jews to the concentration camps that would continue, without pause, for the remainder of the war. Many complied with the order, afraid but not wholly understanding what a terrible fate awaited them.

Margot’s friend Laureen Nussbaum claimed that some of her friends wanted to go when the call-up came. They did not expect anything too bad to happen, but their parents begged them to stay and hide. Other parents made their children obey the call-up, in order to save the rest of the family.

The Franks were in no doubt about what it meant, and Otto had already warned his friends about the true atrocities that were occurring in the concentration camps:

It was said that life in the camp, even in the camps in Poland, was not so bad; that the work was hard but there was food enough, 21and the persecutions stopped, which was the main thing. I told a great many people what I suspected. I also told them what I heard on the British wireless, but a good many still thought these were atrocity stories.

On the day after the call-up, the Franks decided that their only option was to immediately go into hiding. Swiftly they left their apartment at Merwedeplein for the final time, leaving behind clues that they had fled to Switzerland – and abandoning, much to her distress, Anne’s beloved pet cat. On 6 July 1942, Otto, Edith, Margot and Anne entered their hiding place in the annexe of 263 Prinsengracht, and life for all of them changed irrevocably.

The family would live in the annexe for more than two years, sharing five small rooms with four others – a family they were already acquainted with, Hermann, Gusti and Peter van Pels, who joined them on 13 July 1942, and then dentist Fritz Pfeffer, who arrived on 16 November.

It is this group, with their daily activities, their hopes and fears and the shifting dynamics of their relationships, that is so evocatively chronicled by Anne in her diary. In it she writes of her teenage troubles with her mother, her ever-closer relationship with Otto, her growing sexual awareness, the day-to-day irritation of those around her – in particular Fritz Pfeffer, whom she was forced to share a room with – and her blossoming romance with Peter van Pels. Yet her diary is far from just a record of the minutiae of daily life; in it she notes down stories, edits her own previous entries, plans to become a great writer and looks out on the chestnut tree growing in the yard backing onto 263 Prinsengracht, with dreams full of freedom and the future.

Otto, who had previously been nervous and drawn, became a 22supremely calm and unifying figure, structuring the days of the people in the annexe to give a feeling of purpose. Miep Gies noticed that he carried a new sense of composure and displayed a veneer of total control:

Only with a certain time allocation laid down from the start and with each one having his own duties could we have hoped to live through the situation. Above all the children had to have enough books to read and learn. None of us wanted to think how long this voluntary imprisonment would last.

Under Otto’s leadership, they followed a silent timetable of reading, writing and studying in the day. When the offices below were closed, they could then speak, play music and board games and recite poetry. Under the leadership of Edith and Fritz, the group celebrated the Friday-night Sabbath and religious holidays and cooked Jewish recipes.

‘I have to say that in a certain way it was a happy time,’ Otto later wrote. How fine it was to live in such close contact with the ones he loved, to speak to his wife about the children and future plans, to help the girls with their studies, to read classics with them and have discussions about all kinds of problems and all views about life. All this would not have been possible in a normal life, when he was working all day. ‘I remember very well that I once said – when the Allies win, and we survive, we will later look back with gratitude on this time that we have spent here together.’

Those familiar comforts could not keep the world at bay, however, and as they crowded around the radio in the evening, they listened with trepidation to news about the war and Nazi 23atrocities. Otto said the radio connected them to the world, but prohibited BBC broadcasts told that Jews were regularly being killed by the Nazis by machine-gun fire, hand-grenades – and even by poisoned gas.

Nor was their family time free of the tensions and strains that might be imagined if eight people are crammed into confinement together for two years. Anne wrote unapologetically about her emotions at this time, and it was many of these entries that were controversially edited or excluded by Otto from the first versions of the published diary in the late 1940s.

In an entry on 3 October 1942, relatively soon after they entered captivity, Anne wrote,

I told Daddy that I’m much more fond of him than Mummy, to which he replied that I’d get over that … Daddy said that I should sometimes volunteer to help Mummy when she doesn’t feel well, or she has a headache; but I shan’t since I don’t like her and I don’t feel like it. I would certainly do it for Daddy, I noticed that when he was ill. Also it’s easy for me to picture Mummy dying one day, but Daddy dying one day seems inconceivable to me.

Otto edited this entry substantially in the first published diary, wanting to spare his wife’s memory and writing, ‘In reality she was an excellent mother, who went to all lengths for her children.’

Other entries vanished completely, including this one:

I used to be jealous of Margot’s relationship with Daddy before, there is no longer any trace of that now; I still feel hurt when 24Daddy treats me unreasonably because of his nerves, but then I think, ‘I can’t really blame you people for being like that, you talk so much about children and the thoughts of young people – but you don’t know the first thing about them!’ I long for more than Daddy’s kisses, for more than his caresses. Isn’t it terrible for me to keep thinking about this all of the time?

In the closing paragraphs of the diary, Anne expresses her fury at her mother:

I can’t talk to her. I can’t look lovingly into those cold eyes, I can’t. Not ever! If she even had one quality an understanding mother is supposed to have, gentleness or friendliness or something, I’d keep trying to get closer to her. But as for loving this person, this mocking creature – it’s becoming more and more impossible every day!