Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

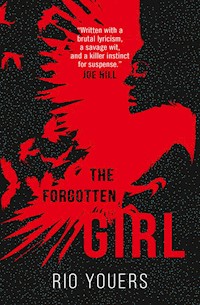

A dark mystery unfolds in Rio Youers's riveting tale, for fans of Paul Tremblay and Joe Hill.Harvey Anderson is a twenty-six-year-old busker who enjoys his peaceful life, but everything is turned upside down when he is abducted and beaten by a group of nondescript thugs. Working for a sinister man known as "the spider", these goons have spent nine years searching for Harvey's girlfriend, Sally Starling. Now they think they know where she lives. There's only one problem: Sally is gone and Harvey has no memory of her. Which makes no sense to him, until he discovers that Sally has the unique ability to selectively erase a person's memories. An ability she has used to delete herself from Harvey's mind. But emotion runs deeper than memory, and so he goes looking for a girl he loves but can't remember... and encounters a danger beyond anything he could ever imagine. Political corruption and manipulation. A serial killer's dark secrets. An appetite for absolute, terrible power... For Harvey Anderson, finding the forgotten girl comes at quite a cost.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 554

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Also by Rio Youers and Available from Titan Books

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Acknowledgments

About the Author

THEFORGOTTENGIRL

Also by Rio Youers and available from Titan Books

Halcyon (July 2018)

THEFORGOTTENGIRL

RIO YOUERS

TITANBOOKS

The Forgotten Girl

E-book edition ISBN: 9781785659850

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First Titan electronic edition: May 2018

Names, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© 2018 Rio Youers

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

What did you think of this book?

We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at: [email protected], or write to us at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website.

For Emily, Lily, and Charlie

Family Hug

ONE

I’m not a coward. This will become evident as we move forward, but I want to put it out there nonetheless. A definitive, no-bullshit statement: I am not a coward. I’ll admit that I’m sensitive, and that my stomach tightens at the mere suggestion of confrontation; I’ll walk away from an argument before it gets too heated. I inherited this from my mom: a gentle-hearted pacifist and vegetarian who, like Linda McCartney, died of cancer anyway. Violence is how stupid people negotiate, she once said to me. I was maybe twelve or thirteen at the time. I smiled and told her that she was brilliant and beautiful. I’m paraphrasing Asimov, she replied, kissing my forehead. Mom never took credit for anything.

I got into a few scrapes in high school. It happens when you’re just south of ordinary. I was never the instigator, though, and I always tried to make peace. It’s not that I was afraid of getting hurt; I simply found the whole exchanging-blows thing unnecessary. So I proffered the white flag and bore the chickenshit denomination. I could forgo being popular for those few ugly years of adolescence, if it meant keeping my integrity. But allow me to state again: I am not a coward. I wasn’t in high school, and I’m not now. I just have zero capacity for violence.

Or so I thought.

* * *

His fist jackhammered the left side of my face—three swift, blunt blows that sent fluorescent particles swirling across my field of vision. The pain felt as if it were wrapped in cloth: a thing both large and round-edged. My cheek swelled and blood spouted from a cut beneath my eye. I slumped to my knees. My emotions shifted from fear and confusion to outright terror. These men were going to kill me.

I crawled a short distance and watched the blood drip between my hands. I imagined them having to scrub it later with bleach, perhaps using a toothbrush to get into the fine cracks in the cement. They would dispose of my body efficiently. My crazy father would assume I’d been abducted by aliens.

“Please . . .” Blood dripped from my mouth, too. The inside of my cheek had been smashed against my teeth.

Another thug—boots like Frankenstein’s monster—kicked me in the stomach and all the air rushed out of me. I rolled onto my side, knees drawn to my chest. More of those fluorescent particles whirled before my eyes. I blinked them away and staggered to my feet. There was another thug—how many of these guys were there?—guarding the door and I stumbled toward him. I thrust my shoulder into his chest and bounced off him. He shoved me back into the middle of the room. I turned a slow circle, wiping my face with trembling hands.

“What do you want from me?”

My vision swam. Five of them. No . . . six. Maybe seven. They surrounded me, as robust as trees, and all grim-faced. That was when I started to cry. And no, that doesn’t make me a chickenshit. Jesus, I was terrified—anybody would cry. Even those ballsy, testosterone-jacked Neanderthals from high school.

My tears brought no pity, though. No reprieve. Some brick-headed dude with fists as hard as bowling balls dropped me with one punch. My head struck the cement floor and chimed. I felt it then: the first toxic pangs of rage. I thought of the many confrontations I’d turned my back on—the punches I could have thrown but hadn’t. It was like I had banked all my aggression and now I was cashing it in. Adrenaline surged like a whale breaching. I got to my feet and made fists of my own. Be damned if I’d go down without a fight.

I stepped toward the thug with the monstrous boots and threw a sizzling right hook. I imagined it an asteroid that would impact the planet of his skull and split it to the core. Instead, I tripped over my own feet and my fist sailed harmlessly wide. I caught my balance in time for one of those boots to connect with my bony ass. Down I went again. The rage was flushed from me, as if it had never been there to begin with. I curled onto my side and whimpered. Thug one—Jackhammer—rolled me onto my back. He placed his foot on my chest like a victorious barbarian.

“Tie this skinny motherfucker up,” he said.

* * *

So I have this theory: that we all have tunnel vision; we move through life seeing only what’s directly in front of us, with little interest in the periphery. I mean, when was the last time you really looked around, a 360-degree appreciation of your environment, where you note—at once—the architecture of that building, the sun-washed red of that stop sign, the black car idling in a different spot every day? We see these things, but—because they exist beyond the conveyor belt of our lives—we rarely absorb them. It’s a remarkable form of blindness.

My old man once claimed that we have microchips implanted into our brains at birth, that we’re essentially automatons hardwired to certain corporate logos and propaganda. Conspiracy-theorist paranoia, of course, but I can’t help but believe that something is scrambling the signal. Something is blinding us.

They’d been watching me the past few days. That black car idling first outside the Bank of America, then in the Cracker Barrel parking lot. That stranger standing two behind me in the line at the post office. That brick-headed dude walking past my apartment every few hours, often wearing a different jacket. They occupied the periphery, but I didn’t really see them because I—like everybody else—have tunnel vision.

It had been an average Tuesday: get up at 9 a.m., a breakfast of quinoa flakes with almond milk, thirty minutes of Ashtanga yoga, shower and teeth. Tuesday mornings I busk beneath the Tall Man statue in Green River Park. It’s a sedate vibe, where people go to read, relax, just be. I play Joan Baez, James Taylor, Jim Croce. Mellow tunes to complement the setting, and the money in my guitar case at the end of the session suggests that people appreciate it. Tuesday afternoons I hit the sidewalk outside the Liquor Monkey, where I break out the blue-collar rock. After a couple of hours there, I go to the bank to unload the small change. Then I buy bread, return to Green River Park, and feed the birds: a little spray of color at the end of the day. Sometimes I’ll play to them, too. Sweet acoustic melodies. Birds dig it.

Average Tuesday, then I returned home and everything was turned upside down. The door to my apartment hung ajar and I stepped inside tentatively, wondering if Mr. Bauman, my landlord, had let himself in for some reason, and forgot to close the door afterward. Stepping into my living room, I saw this wasn’t the case: my apartment had been ransacked. Bookshelves had been cleared. Drawers had been emptied. Chairs were overturned and my few pictures shattered in their frames. In the bedroom, my clothes were strewn across the floor and my mattress flipped. There was similar disarray in the kitchen and bathroom. I dropped my guitar and it struck a muted, tuneless chord from inside the case.

“What the hell?” I said. There was too much chaos to tell if anything was missing. I stepped into the kitchen, where I kept a roll of twenties—maybe four hundred dollars—in a Ziploc bag at the bottom of an empty cookie jar. The jar was broken. The money was still there.

“What the hell?”

My computer hadn’t been stolen, either, but I suspected it had been tampered with. I always put it into sleep mode and closed the lid, but now it was open and wide awake, my Beatles-themed screensaver going through the motions. It occurred to me then that whoever had turned over my apartment wasn’t interested in money. They wanted information.

A case of mistaken identity. Must be. Because I had no information. I was a twenty-six-year-old street performer from Green Ridge, New Jersey. I didn’t mingle in other people’s affairs. I kept blissfully to myself. Just south of ordinary, remember?

Something else occurred to me: that the door to my apartment hadn’t been forced, which meant they’d either picked the lock, or Mr. Bauman had let them in. I thought I should pay him a visit—he’d need to know what had happened anyway—before calling the police.

The landlord’s apartment was on the first floor (I was on the third) and the quickest way down was the stairwell. The elevator worked but it was slow as hell and swayed ominously as it descended. I’d just rounded the second flight of stairs when I came across two of the thugs blocking my way to the exit. Even then it didn’t click—I didn’t see them. I scooched to one side so we could pass without bumping shoulders, but instead one of them grabbed my T-shirt and threw me against the wall. My head cracked off the concrete and I saw the first of those fluorescent particles. I realized then that—for some unknown reason—I was in shit of the deepest variety.

I tried doing what I always do in the face of confrontation: I turned away. Or in this case, ran away. A deft spin-move took me out of the thug’s clutches and I darted toward the stairs, heading for the second floor. Footsteps echoed around me. I looked up and saw another thug—Brickhead—descending from the third. Only one option available: I crashed through the doorway onto the second floor and staggered toward the windows at the far end of the hallway. The fire escape was only accessible through the apartments, but I hoped—courtesy of too many cheesy action movies—that I might be able to leap into a dumpster, or perhaps onto the back of a truck.

Voices behind me: thug one and thug two, with their unmoved expressions and granite shoulders. I passed the elevator and saw it standing open. It appeared I had another choice after all. The doors rattled closed as I reeled toward them, but I squeezed through the gap and into the stale-smelling cube. I saw the thugs in the inch-wide strip of hallway before the doors came together. Frantically, I punched P for the parking garage. There was a moment’s hesitation—a pondering of counterweights and pulleys. I thought the doors would obligingly open again, allowing my pursuers access, then I heard a reluctant ding and the car began its descent.

Slowly.

There was a dulled mirror on one side and I noted my reflection wildly drawn: screwball cousin to the coolheaded dude who’d sat down to his quinoa flakes that morning. The car swayed and clanged like antique clockwork. I imagined the thugs patiently making their way to the parking garage. The doors would open and they’d be waiting. I tried the emergency button, hoping the car would stop—that the frickin’ Bat-Signal would illuminate the sky over Green Ridge. The red light above it sputtered but that was all. “Help me,” I shrieked, jabbing the button like a kid with a video game. “This is Harvey Anderson, apartment eighteen. I’m being—”

Cables swinging, creaking. The car stopped with a bang. I wondered if the emergency button had worked, after all, then the floor indicator displayed a mockingly bright P and the doors rumbled open.

The thugs were there. Four of them. They weren’t dressed like secret service agents, and were nothing like the muscle you see on TV. They didn’t have eye patches or neck tattoos. These looked like regular guys. Jeans and jackets. Designed to blend into the periphery.

“You’ve got the wrong man,” I said.

One of them stepped into the elevator. A baton telescoped from his sleeve. It swept toward me with a hummingbird purr—caught the ridge of bone behind my right ear. I went down and wavered for a moment on the rim of consciousness. Another thug placed a cloth bag over my head. It smelled of oil. I dampened the fabric as I sucked for air.

And then . . . nothing.

Nothing until I came to in a small room with a cracked cement floor and cinderblock walls. A dim lightbulb buzzed behind a wire mesh set into the ceiling. A tender bump had risen behind my right ear and I examined it gingerly. It felt as large as a knot in a bed sheet.

The thugs circled me. I pushed to my knees and implored the blurred face of the one closest.

“What the fuck, man?”

They came at me.

Jackhammer first.

* * *

I was pushed into a creaky wooden chair and my wrists bound to the slats behind me. I bled onto my T-shirt and screamed. The thugs waited for me to burn myself out. My blood darkened and dried.

Jackhammer stepped toward me. I flinched as he reached out, placed his fingers beneath my chin, and tilted my head so I could see him.

“And now it’s down to you,” he said.

I rasped something. Begged him with my eyes.

“We’ve shown you how serious we are.”

My blood was smeared across his knuckles.

“What do you want?” I asked.

“Information,” Jackhammer replied. “Cooperate and we’ll let you go. Hold back and we’ll kill you.”

There was no character to his voice. It could have been his shadow speaking. His face, too, was remarkably blank. No moles or scars. His eyes were not a striking shade of blue and his nose not too flat. I imagined describing him to police as “nondescript” and having them roll their eyes. The facial composite would look as generic as a grapefruit.

He removed his fingers from beneath my chin. My head slumped.

“It’s your choice,” he said.

“You’ve got the wrong man,” I said.

“Harvey Nathanial Anderson. Born: zero-four, zero-four, eighty-nine. Mother: Heather June Anderson. Deceased. Father: Gordon Anderson. Served with the Ninth Infantry Division in Vietnam. Lost the left half of his face to fragments from a Viet Cong grenade.”

Lost his mind, too.

“How am I doing, Harvey?”

“Is this about my father?”

“Your father doesn’t concern me,” Jackhammer said. “To be honest, you don’t concern me, either.”

“Then what is it about?”

His nostrils flared as he inhaled. He brought his hands together in a bony ball and leaned forward, studying my expression, looking for any hint of recognition.

“Sally Starling,” he said.

There had been three unsolved murders in Green Ridge in the last three years. All women. Beaten, raped, stabbed to death. The killer was extremely careful, leaving no incriminating evidence. For a while the town was at condition orange. We even checked our peripheries, like the entire nation in the months following 9/11. It must have worked, because there hadn’t been a murder for sixteen months. The townspeople had since slipped into their usual zombie state.

That name—Sally Starling—was vaguely familiar, and I wondered if she’d been one of the three victims. Perhaps if I hadn’t been so scared, I could have identified it, but all I found in my mind was an empty space.

“I don’t . . .” Tears filled my throat. I inhaled sharply and the sound was drain-like. “It’s not . . . please—”

Jackhammer’s fist drummed off my jaw and the chair teetered sideways. A flare exploded in my skull and set an alarming glow over everything.

“Did I mention how serious we are?”

I spat a red ribbon from my mouth.

“Sally Starling.”

He pronounced the name slowly. Four precise syllables. I churned through my bruised mind but there were only blanks. A terrible thought occurred to me: that if Sally was one of the murder victims, these guys likely believed I was her killer. They could be vigilantes, or Sally’s stricken family, taking the law into their own hands.

I lowered my eyes and groaned miserably, then recalled Jackhammer saying that they wanted information. Cooperate and we’ll let you go, he’d said. It didn’t jive with the vigilante theory.

“I don’t . . . don’t—”

He hit me again. More an open-handed slap. My head rocked to the side so viciously that capillaries erupted in my neck.

“NO,” I screamed. “Jesus fucking Christ.” I coughed up blood and snot and spat it down the front of my T-shirt. The pain encircled me. “I’ll help you if I can. I swear. I fucking SWEAR.”

Jackhammer’s lip flared. He flexed his fingers.

“Sally Starling,” he said. “Where is she?”

“I don’t know, man. I don’t even know who she is.”

“You’re lying.”

“I swear.”

“WHERE IS SHE?”

That diamond of a fist drew back yet again and I braced myself, thinking the next blow would shut out the lights, perhaps cause permanent brain damage. I thought, bizarrely, of Swan Connor, Green Ridge’s celebrity resident. Swan had been a big-time record producer in the seventies and eighties—back when people actually bought records and there was money to be made. He was always so engaging and bright, happy to share an anecdote or a smile, but a recent stroke had turned him into a maundering imbecile. I’d seen him just the week before, stumbling down Main with the aid of two canes. He was drooling like a teething infant and had a thick green booger on his upper lip. That would be me after this punch landed. There’d be deep crevasses in my brain where cognitive functions and motor skills used to live. I would eat mashed potatoes with plenty of ketchup. I would wear eight-dollar track pants and maunder with Swan.

I waited, but the punch never landed. Another thug had stepped forward and placed his hand on Jackhammer’s chest.

“She got to him,” he said.

“I know,” Jackhammer said.

“She’s powerful.”

“I know that, too.”

I had no idea what they were talking about, but—for the time being, at least—the beating had stopped and that was a positive. Albeit a meager one. I lowered my head and started to cry again. Jackhammer loomed over me. He rolled back my head and used his thumb and forefinger to peel my swollen eye wide.

“We should make sure,” he said.

* * *

We often think of our memory as a vast library containing volumes of information—a place where “books” are stored and sometimes lost. It’s a romantic notion, but an inaccurate one. In truth, it’s more like a factory, with forklifts speeding along the neural pathways and production lines operating 24/7. In recalling a childhood Christmas, for instance, we don’t send some dusty librarian to hunt through the holiday department, but rather assemble a team of neurons from pertinent regions of the brain to encode and reconstruct the desired memory. It’s an efficient system, but complex and susceptible to malfunction.

Memories deteriorate. They get lost forever. I don’t know—nobody does—whether they actually disappear, or if the conjunctions necessary to reconstruction become damaged. I favor the latter theory. You ever smell something—a perfume, home cooking—that whips you back in time, floods your brain with recollection? Sure you have. I like to believe that all lost memories are equally recoverable. They just need the correct stimulus.

It’s a little different when certain memories have been stolen—plucked from your head like they were never there to begin with. Scientists argue that this isn’t possible, but I know that it is.

“We need to find her.”

“I can’t help you.”

“We’ll see about that.”

Jackhammer had procured a chair from somewhere and sat opposite me. His expression hadn’t changed. He could have been waiting for a bus. Again, I considered my father’s theory about microchips in the brain and automatons. Maybe he wasn’t so crazy.

“We are proceeding under the assumption that you are telling the truth, and that Ms. Starling has performed her little party trick on you.” He linked his fingers and leaned toward me. The chair creaked, offering the impression of a tree bowing in the wind. “Let’s just see if there’s anything left.”

I nodded, as if that were all fine with me. As if they were suddenly being reasonable. Something warm trickled from my swollen left eye.

“Sally Starling isn’t her real name,” Jackhammer said. His blank eyes felt like the backs of cold spoons, placed on my cheeks. “She was born Miranda Farrow, June 1991. That makes her twenty-four years old. She used the name Charlotte Prowse after her parents abandoned her at age fifteen, then became Sally Starling when she moved to Green Ridge six years ago. Places of employment include Marzipan’s Kitchen, Pennywise Used Books, and the Health Nut.”

I knew those places well, but nothing stirred in my brain.

“Her last known address was apartment eighteen, Passaic Heights, Green Ridge, New Jersey.”

My address.

“We spoke to the landlord: Mr. Ralph Bauman. He told us that you and Ms. Starling had been living there for five years. Good tenants. Quiet. Always paid your rent on time. He hadn’t seen her for a week or so, but had no reason to believe she’d moved out. She certainly didn’t notify him. No forwarding address or number where she could be reached.”

“This is . . .” I couldn’t find the right words. My body was slumped and something inside my skull hissed like a cracked pipe. “This is all news to me.”

A folder appeared in Jackhammer’s hand. I didn’t see which of the thugs had handed it to him. Possibly the one who purchased his footwear at the same place as Frankenstein’s monster. From it, Jackhammer pulled a sheet of paper. He studied it for a moment, then held it up for me to read.

“The rental agreement for your apartment,” he said. “Signed August twentieth, 2010, by co-tenants Harvey N. Anderson and Sally Starling. Tell me, Harvey . . . is this your signature?”

I looked at my strike-through scrawl, identifiable even through the tears in my eyes, and nodded. Sally Starling’s signature—a vivacious, bubble-like cursive—sat beside mine. I was positive I’d never seen it before.

“Mr. Bauman was kind enough to make a copy,” Jackhammer said. I thought I detected a smile in his voice, but when he lowered the agreement I saw that his mouth was a humorless gray line. “We can be very persuasive.”

“Yes,” I said stupidly.

“Jogging any memories, Harvey?”

“No.”

“Nothing?”

“Nothing.”

He blinked, slid the agreement back into the folder, and took out a color photograph. It was a headshot. Sally Starling, I assumed. Tousled, mousy hair. No makeup. The kind of girl my heart gallops for. She had a zit on her chin that she hadn’t tried to hide. There was a crusty something—perhaps dried tzatziki—on the bib of her Health Nut apron.

“Seems absurd,” Jackhammer said, “to ask if you recognize a woman you lived with for five years.”

“I don’t recognize her,” I mumbled. The woman in the photograph—agreeable as she was in her crunchy, au naturel way—was a stranger to me.

“Very private, your girlfriend,” Jackhammer said. “Very careful. Like you, she doesn’t own a cell phone or subscribe to social media—the things that tie you to society. It was difficult to find a current photograph of her. But once we determined her location and the alias she’d adopted, we found this: the Health Nut’s employee of the month for February 2015.”

I looked at her again, because it was far more appealing than looking at my blood on the floor, or any one of my dour tormentors. She had hazel eyes, the color of turned leaves, and her nose was slightly off-center. Her face shape, though, was perfectly oval, and I imagined how it would complement the cup of my palm—how I could cradle her brow or jaw, and it would be the counterpart to my hand. I wondered if the rest of our bodies would enjoy a similar harmony, and if we’d make love like strawberries and cream.

“Anything, Harvey?”

And yeah, there was . . . something. But was it a memory, or imagination? I closed my eyes and concentrated. A woman, swaying her hips to music I couldn’t hear. Her dress was knee-length. It switched between blue and yellow.

“Harvey?”

“Dancing,” I said distantly.

“Sally?”

Impossible to tell. She had no face.

“Tell us what you see.”

That blue/yellow dress flickering around her knees. Her arms making flowing motions. I pushed deeper, but there was nothing more. It was a sketch done in pencils, partially erased.

My eyes crept open. Jackhammer was leaning forward in the chair, only inches from me. I could smell his breath, which had decidedly more personality than his face.

“Harvey?”

“I think I’ve been brainwashed,” I said.

He stood quickly and the chair toppled backward. I though the was going to beat the dancing woman from my mind. Instead, he ran a hand through his average hair, righted the chair, and looked at the others.

“Make the call,” he said.

* * *

I can’t tell you how long I was in that boxlike room, alone and bleeding, tied to a chair. There was no window, so I couldn’t use the light to measure time, and my body clock had been damaged by Jackhammer’s fists. It could have been a day, or three days, or a week. I faded in and out like a ghost in an old movie, never unconscious or asleep, but caught in a surreal daze where pain and fear were ever present. My throat was too dry to scream.

Escape was out of the question; I was too weak, and the thugs kept guard outside the door. I heard them shuffling their feet, clearing their throats. If they spoke to one another, I didn’t hear them. I told myself that if they were going to kill me, they would have already. It was a small comfort.

So time passed in mysterious excerpts. I suffered deeply and prayed shallowly, and worried for my father, whom these thugs knew all about, and who was delicate and paranoid. I imagined them bringing him here, wide-eyed and confused, and Jackhammer pressing a gun to his forehead. Dig deep, Harvey, the thug would say expressionlessly. Tell us about the dancing girl. And my old man would puff out his chest and regard me through his single whirling eye. Goddamn Russian sleeper agents, he’d say. The red hammer is falling.

My wrists flexed weakly at the rope binding me to the chair. I counted my pains and wept. It felt like a circular saw was buzzing around the inside of my skull, scoring the bone, and with any sudden movement my head would fragment like a fortune cookie. My dreadlocks—clotted as cows’ tails—had absorbed blood like sponges.

I faded in . . . and out.

Was it average Wednesday? Or slightly-better-than-average Friday?

Out . . . and in.

Three words kept floating into my mind, and sometimes they’d lodge there like arrows in a bull’s-eye: Make the call. What did that mean? Who were they calling? It couldn’t be good, right? Let him go. Now that was good. But make the call . . . no, that sent unpleasant vibes racing through me.

I default to my mom in moments of duress. She was a beacon of strength—my only beacon of strength—when she was alive, and I could always rely on her celestial wisdom. On this occasion, however, I turned to the girl without a face—the dancing girl. She lured me with the timing of her hips, the flash of her dress, and I went to her meekly. Who are you? I asked, stepping into the partially erased scene. Why can’t I remember you? I took her featureless face in my hand and cradled it perfectly, and I knew for certain, from somewhere deeper than my mind, that this was a memory.

Who are you?

I felt the tick of her hips against mine. The warming pressure of her breasts. I searched for greater detail—my brain fighting to pull together elements that simply weren’t there. I cupped the other side of her face and that, too, was perfect.

Sally . . . is that your name?

Her hair smelled of nothing. Her skin smelled of nothing.

Why can’t I . . . ?

Time passed. Sometimes I was wide awake, with a wildfire of emotion burning through me. Other times I slumbered in that exhausted daze. Eventually, the door opened and Brickhead strolled in. He placed smelling salts beneath my nose and I popped to full alertness. A series of cracked sounds eked from my mouth. He held a small glass of water to my lips and I drank with my throat pumping.

“Please let me go,” I said, and followed him with my eyes as he left, slamming the door behind him.

Sally danced in my mind.

Make the call.

Moments later the door opened again, and in crawled the spider.

TWO

He was an older man—just into his sixties, I thought—with a pale, lined face and dark eyes. His forehead was dominated by angular eyebrows and a silvered widow’s peak that glimmered in the overhead light. He wore an unremarkable gray suit, given character by a red flower pinned to his lapel.

“Harvey,” he said. His voice was sure and strong. I detected a hint of the South in his accent. He took the seat opposite me (a pillow had been placed on it, I noticed), his long arms and legs folding neatly as he made himself comfortable.

“Who are you?” I asked.

“I see my hunt dogs have been heavy-handed with you.” He gestured with one finger at my battered face. “They find the aggressive approach to be expedient. I’m always called upon as a last resort—when their weakling minds are empty of ideas.”

The thugs appeared unfazed by this insult. They formed a semicircle behind the older man.

“Who are you?” I asked again.

“You”—the finger pointed now, straight as a ruler—“don’t need to know. Suffice to say that Miranda Farrow—or Sally Starling, as you know her—knows me very well. Almost as well as I know myself.”

I shrugged and winced, then shifted in the chair. My left leg was numb. I imagined that if they ever cut my binds, it would take me ten minutes to stand. Another twenty to walk to the door. The man in the suit watched me, breathing coolly.

“I need to find her,” he said. “She took something extremely valuable from me.”

“And you think I know where she is?”

“That’s what I’m here to find out.”

“Are you going to torture me?”

A thin smile touched his lips. He regarded me with those Emperor Ming eyes, and I could only imagine the wickedness behind them. A new, great fear rose through my stomach and lodged in my throat. I lowered my head and trembled.

“We searched your computer as well as your apartment,” he said. The smile had slipped from his face but that cool air remained. “We went through all your files and folders, your browsing history, your e-mail. Came up empty. But it’s easy to erase data from a computer. You just right-click and hit delete. Empty your trash and it’s gone forever. You can even wipe your entire hard drive. It’s effortless.”

This was a nightmare. It had to be. A long, brutal nightmare.

“The human brain is a wildly different creature,” he continued. “We immodestly think of it as some kind of supercomputer, but it’s far more complex. We have our instincts, our emotions, our memories. A surfeit of knowledge and experience. Erasing this data is more demanding than a simple right-click. There are methods, of course—lobotomies, electroconvulsive therapy—and medications that repress emotional triggers. But to go into the brain and hand-select certain memories for deletion . . . impossible. So how do we begin to explain what has happened to you?”

I shook my head. My eye was drawn to the red flower on the man’s lapel. Two shades lighter than my blood.

“Your other memories are intact,” he said. The lines at the edges of his eyes deepened. “You know your name, where you live, where you went to school. I’m sure you remember events from your childhood, computer passwords, the lyrics to your favorite songs. Everything appears in working order. And yet you cannot remember the woman you lived with for five years.”

“I still think you’ve got the wrong man,” I said. “You tell me I know this woman, but the only proof you’ve got is a rental agreement that could’ve been forged. So what are you going to do? Torture me—kill me—for information I don’t have?”

“I know this is upsetting for you.”

“Just let me go.”

He sat back in the seat and regarded me silently. His eyes were like hands, touching where they shouldn’t.

“I can’t help you,” I said.

“I need to be sure of that.”

“But I don’t—”

“It’s incredibly difficult to track a person who leaves such dainty footprints.” He smiled again. Full and false. “Miranda—sorry, Sally—puts down few roots, and adopts an unremarkable image so that she doesn’t stand out.”

I considered the periphery and sighed.

“No driver’s license, social security number, or passport. She worked for mom-and-pop stores and was paid under the table, limiting her paper trail.” His eyebrows came together, forming a bird shape across his forehead. Not a sparrow or chickadee, either, but a raptor. Something with claws. “Nonetheless, my hunt dogs sniffed around Green Ridge. They discovered where she lived and worked, and that her boyfriend busks for quarters outside the Liquor Monkey. Other than that—and although she lived in Green Ridge for six years—nobody knew anything about her. A dainty footprint, indeed.”

The thugs stood silently, like monoliths, staring straight ahead. Hunt dogs, the man called them. I wondered how much power he wielded and felt sick inside.

“That doesn’t explain why I can’t remember her,” I said.

“Then allow me to spell it out for you,” the man said, and I detected the first suggestion of impatience in his voice. “Sally Starling possesses a unique and powerful ability. Just like we can erase data from a computer hard drive, she can—selectively—erase the memories from a person’s mind.”

“Bullshit,” I said. Growing up with my old man—who believed in government-engineered hurricanes and little green men—I had become remarkably adept at sniffing out bullshit. Hell, I was a hunt dog for bullshit.

“She fled Green Ridge a few days ago, a frightened girl, no doubt, forced to begin a new life in a new city, with a new name and a fabricated background. Before leaving, she cleared your apartment of anything that could be associated with her. Photographs. Clothes. Possessions. Any triggers . . . gone. There’s nothing on your computer, so it’s fair to assume she scrubbed that data, too. Simply accessed the relevant files and hit delete. She did the same thing with your mind.”

“Bullshit,” I said again, but my heart made a forlorn, hurt sound in my chest, and that sickening feeling deepened. “You’re saying this woman—my so-called girlfriend—deleted parts of my mind?”

“Your memories, yes. Specifically, your memories of her.”

“Why would she do that?”

“Because her life is fraught with danger, and she doesn’t want you involved.” He spread his long-fingered hands. “This is the only way she could make a clean break without worrying that you might follow.”

“I guess she didn’t count on you guys getting to me.”

“She knew we’d find you, I’m sure, but likely thought your absence of memory would protect you.”

The bird shape took wing again. His dark eyes gleamed.

“She was wrong.”

* * *

“As I’ve already noted, the human brain is expansive and intricate. Given the additional complexities of memory, it’s entirely possible Sally left something in your mind.”

I closed my eyes and there she was, swaying her hips, matching the rhythm of a song I couldn’t remember.

“Even if she has,” I began hesitantly, my good eye slowly opening, finding that red flower again. “Even if I suddenly remember everything about her, I still wouldn’t know where she is. If what you’re saying is true, she would never have told me.”

“That’s true, but in the time you spent together, she may have mentioned something—a longing, a wanderlust—that could offer some clue as to where she went.” He extended his upper body toward me, his hands curled into bony fists. “That’s all we want, Harvey. A slice of information. A partial of that dainty footprint.”

“I’ve got nothing,” I said. “I’m a waste of time, I promise you.”

“He remembers something about a dancing girl,” Jackhammer offered.

“That could be anyone,” I said, knowing it wasn’t. “A scene from a movie. A drunk aunt at a wedding.”

“Explore it,” the man in the suit said.

“I have.” I shook my head. It rattled with pain. “It’s too hazy. She doesn’t even have a face, for God’s sake.”

“We’ll soon see,” the man said. He receded into the seat and breathed deeply. I sensed the tension illuminating his chest, like neon in a plasma globe, that would snap colorfully toward me if I dared touch him. Not that I could, of course. Or would. My fear, already ramped up, created a similar thrum. If we bumped chests, it’d be like lightsabers colliding.

“I want to go home,” I said. A hopeless statement. It made me feel so small.

“Some scientists believe,” the man said by way of a reply, “that when we store a memory, we do so multiple times throughout the cortex. It’s kind of like backing up your hard drive. If information becomes lost or damaged, there are ways of restoring it.”

“Hypnosis,” I muttered.

“Perhaps,” he replied. “Although the theory suggests we draw upon the backup without being aware we are doing so—our brains instantly retrieving information from the nearest undamaged source.”

I looked at his eyebrows again, recalling the hypnotists I’d seen depicted in countless movies and comic books, usually with spiraling eyes and mysterious rays emanating from their skulls. See THE GREAT MESMERO demonstrate his amazing MIND-BENDING abilities. They all had stupid names, and they all had the same eyebrows as this dude.

“Are you going to hypnotize me?”

“No,” he replied. Another thin smile. “My method is far more . . . effective.”

That didn’t sound altogether reassuring.

“But I would like to avoid that,” he said. “If possible.”

“Yes,” I said.

“I need you to explore your memories, Harvey. The smallest detail could unlock any duplicates Ms. Starling may have missed, and trigger at least a partial recall.”

“I tried that already,” I said, gesturing toward the muscle standing blandly behind him. “With your goons—your dogs. I’ve got nothing.”

“I urge you to try again. Try harder.” His upper lip flared. I saw his teeth. Neat and white. “The alternative will not be pleasant.”

A knife held to my throat would not have been more threatening. I swallowed blood and nodded weakly.

“Good.” He leaned toward me again, bowed over his bunched fists. “Concentrate on the dancing girl. Explore her. Every minute detail.”

“There’s nothing to explore,” I said. “She’s dancing. That’s all.”

“Where is she? A party? A nightclub?”

“I don’t know; it’s just an empty space.”

“Is she dancing with you? Are you with friends?”

“I don’t have many friends,” I said. “I find people to be overrated. Go figure.”

“What is she dancing to?”

“I can’t hear anything.”

“Music is a powerful memory trigger.”

“There is no music.”

“Concentrate!” It was the first time he lost his cool. An eruption of anger that had the dull impact of an underwater explosion. I leapt in the seat as much as my binds would allow. Even the hunt dogs flinched.

“I’m trying,” I whispered.

“Not hard enough.” He rose to his feet and took a long stride toward me. I pulled away and almost spilled backward. “Last chance, Harvey.”

His closeness unnerved me. The dice-like clack of his teeth when he spoke. The hollows of his temples, which I could see now, veined with blue and deep enough to cup eggs. He looked like he’d crawled from the pages of a comic book. Not one of the good guys, either. This put me in mind of something my old man always said, that the world had gone tits-up because there were too many supervillains.

“Go deep,” he implored.

I shook my head and sniveled. A string of snot glued itself to my upper lip.

The man retreated. I gazed at that odd red flower as he backed away. His chest crackled impatiently and his nostrils flared. He was hoping for some kind of neural connection—a memory cascade—but there was nothing. If Sally Starling really had removed all my memories of her, she had been incredibly efficient. Only the dancing girl remained, and I began to wonder if that was deliberate.

“Okay,” the man said. “It’s time to do this the hard way.” His long body affected a precise right angle as he leaned forward. I noticed his flower wasn’t a flower at all, but a cluster of red feathers.

“The hard way?” I said. Voice like ash.

He wasn’t smiling anymore.

* * *

He looked at the thugs—the hunt dogs—and nodded once. Frankenstein’s Boots broke from the semicircle, left the room. The door slapped closed behind him. I smelled dust and rusty water. I’d thought I was in the basement of some old house, but imagined now an abandoned warehouse with a polluted stream running beside it. The kind of place where bodies were dumped.

“What’s going on?” I searched the man’s dark eyes, my shoulders rolling as I struggled against the ropes. “I told you everything I know.”

He nodded, as if he believed me, when clearly he did not. The heels of his fine shoes tapped off the cement floor as he stepped closer. Would he wipe the blood off them himself, I wondered, or have one of the hunt dogs do it for him?

“Please,” I begged. “Whatever you’re thinking of doing—”

“I need to look for myself.”

“What? I . . . what?”

“This will be excruciating,” he said. “Not so much pain, but an unfathomable sense of violation. You will cry and scream and plead. It will feel like your brain is being unspooled from the inside out.”

“No—”

“Like your mind has been raped a thousand times.”

“Please, no—”

“And when I’m finished, you’ll feel haunted, degraded, and shared.” The bird on his brow again. A savage thing, and so close. “The nightmares will never stop.”

The door opened. Boots entered pushing a wheelchair ahead of him. An oxygen mask was looped over one of the handles. The sight of it silenced me. I blinked in shock. The fear now was beyond scale, shaped like a thing reaching.

“What are you going to do to me?”

The man didn’t reply. He took off his gray jacket and placed it carefully over the back of the chair.

“Let’s begin,” he said.

THREE

He crawled into my mind. Spider. I felt each of his eight legs tapping and the soft thump of his abdomen along my consciousness. It was, instantly, the most harrowing and invasive thing I’d ever experienced. Ice replaced the marrow in my skeleton. I screamed and curled stiffly at the waist, as if some drawstring connected to my spine had been pulled tight.

He was cold and slick and plump.

* * *

Now, let’s see . . .

I heard him clearly, as though he’d spoken out loud. That soft, southern tinge. He was inside me, scurrying along my memories and dreams. I tried to shake him loose—jibbing and rattling in my chair—but he held tight. I envisioned the sole of some gigantic sneaker slamming down and crushing his fat body into the grooves of my brain.

A sneaker? That’s cute, Harvey.

“Get out of my—” Blood frothed at the corners of my mouth and I spluttered, drawing deep, gurgling breaths. I finished the sentence in my mind: —FUCKING HEAD.

He skittered, explored. His many legs stretched, touching neurons throughout my brain, acting as conductors that drew the separate elements of memory together. I tried to thwart him, to imagine a blank brick wall, but he was beyond that. He crawled into the folds of my temporal lobe, stimulating electric impulses, uncovering memories with formidable ease.

Is this Mom? Why, she’s pretty.

Fuck you, man.

She stood in a stroke of sunlight at our living room window, her hair so gold it was almost white. I recall this with unnerving clarity; the day she told me she had breast cancer. The memory shifted to her lying in an eco-coffin made from hand-woven rattan and organic cotton. Her face was a pastel mask.

The spider burrowed. I jerked and cried out, the cords in my neck announcing themselves like tension wires.

Get OUT.

Not until I’m satisfied.

They’re my memories . . . MINE.

Mr. Kinshaw, my science teacher in eighth grade, crying at his desk after calling Jermaine Robinson a “stupid little nigger,” knowing his career was over. Sitting alone in the school cafeteria after someone had pinned a sign—STINK-HIPPIE—to the back of my sweater, and it was Mr. Kinshaw who had removed it. Watching my old man sharpen lengths of bamboo for a Vietnamese punji trap he was building in the backyard.

Where is she?

My teeth clattered and blood vessels cracked in my good eye. It felt like I was being electrocuted, but there was no pain, only a stream of cold energy. The chair creaked and scraped across the floor.

Snapshots of my first guitar; my first kiss; combing Mom’s hair while she sang “God Bless the Child”; picking peaches at Uncle Johnny’s farm; jamming with Steve Van Zandt at a bar on the shore; masturbating in the shower; masturbating in the kitchen; masturbating on a train.

The spider crawled. He saw it all.

My memories. My life.

Blood trickled from the corners of my mouth. The ice in my bones melted and I voided myself, bladder and bowel.

The spider said, This hasn’t even started to be uncomfortable yet.

He went deeper.

* * *

And he found her. The dancing girl. He groaned with a sad kind of satisfaction and gathered the memory close, as if it were precious, as if it were his.

There you are. My little bird.

He crawled into the middle of her empty face and paused there. His fat abdomen throbbed as he worked to recall her features, using his legs to bridge damaged connection points, but to no avail; her face—as she had appeared in this moment—was gone. He assembled a likeness based on the employee of the month photograph Jackhammer had shown me, but it wasn’t the same.

I know it’s you. I can feel you.

I felt her, too, and wondered if she was connected to his soul like she was connected to mine. Did our respective—and perhaps opposite—emotions resonate equally?

The spider scurried along the angle of her jaw, onto her throat, then onto her dress. Another pause as he repaired a damaged connection, and her dress stopped switching color. Blue. It was blue. Recalling this singular detail caused a miniature cascade, and the scene gained greater depth.

Her dress was blue. Exactly the same color as the sky. We were outside. A clear, hot day. Sound and smell of the ocean. People milling around. Sunglasses and tanning oils. The wooden planks beneath our feet were laid in a herringbone pattern. In the distance, the faded green shell of a building with punched-out glass and a sign that read CASINO.

Where is this? the spider asked.

It’s the boardwalk at Asbury Park.

When?

I don’t know.

He delved deeper. His long legs ticked and grabbed, the fine hairs on them sensitive to all brain activity. My eyes looped back inside my skull and I yammered senselessly. I felt the warmth of my body waste but everything else was cold.

More detail emerged, like an old film being brought into focus. The boardwalk flushed with life: lovers holding hands, people pushing bicycles, joggers wending like fish, their muscles wet in the heat. The dancing girl laughed and threw her arms wide. Her mousy hair caught the merest breeze and flowed around that invisible face.

You can’t hide forever.

Aromas of grilled fish, lemongrass, coconut. There was a restaurant to the right with boardwalk seating. A three-piece band, tucked in the corner, played their instruments silently. A slow-tempo number, judging from the way they played, and the rhythmic tick of Sally’s hips.

What song are they playing?

I can’t remember.

You’re a musician. Do you recognize the guitar chords?

I was looking mainly at Sally when this memory was recorded, but I caught glimpses: C . . . E-seven . . . G-seven. Could be one of ten—fifty—thousand songs.

That doesn’t help, I said.

His legs curled with agitation. He first explored my brain to see if I was telling the truth, then attempted to repair the damage, hoping the music—such an effective trigger, as he’d already noted—would activate a more detailed cascade.

But the song, like her face, was gone.

* * *

He scurried from my mind in an instant and I screamed, slumped forward. Pressure in my face, like hot dough filling the front of my skull, oozing into the cavities and fissures, cooling slowly. Blood leaked from my mouth and nose. I vomited bile in strands thin as spiderweb.

* * *

I wasn’t the only one hurt and bleeding; the man had slumped into the wheelchair. He wheezed and trembled—made weak grabbing motions with his right hand. Boots stepped forward, looped the oxygen mask over his face, turned it on. The man—the spider—sucked long, clean breaths into his chest. The inside of the mask fogged. Blinking my tears away, I saw tiny drops of blood in the corners of his eyes. His face appeared more deeply lined, and his hair more white than silver.

* * *

I don’t know how long he sucked on that oxygen, his breathing growing deeper, steadier. Maybe as long as an hour. Time was beyond me. Eventually, he lowered the mask and gestured for Jackhammer to come close.

“It’s a long shot,” he said, and coughed. His lips were dry, tinged blue. He took another shot of oxygen, then continued: “Asbury Park, New Jersey. I don’t think she’s there, but sniff around. And go gently.”

Jackhammer nodded. “You want me to go alone?”

“Is Corvino still MIA?”

“Yes.”

“Then no . . . definitely don’t go alone.”

* * *

Jackhammer left with thug four. I prayed it was the last time I’d ever set eyes on him.

“Can you still feel me inside you?” the spider asked.

“I can feel where you’ve been,” I murmured. “Your legs.”

They gave me more water. I drank some of it, but most spilled down my chin. I shivered and ached.

“I still feel the girl.” The spider’s voice was cracked and whispery. His hands trembled when he moved them. “Nine years later, I can feel the impact—the emptiness of what she took from me. A great famishment of the mind.”

I shifted my upper body and groaned. My shoulders throbbed and my wrists felt slick, bleeding where the rope had chafed them.

“She took memories from you,” the spider continued. “But you feel no emptiness. And why? Because she was like a surgeon, operating so precisely and efficiently that you’re unaware of anything missing.”

I considered this enigmatic girl, blithe enough to swirl in the ocean breeze, dangerous enough to excise entire moments from my life. She terrified, fascinated, mystified me. I wanted to track her down and reclaim my memories. I wanted to run away and never look back.

“With me, she was a bird—a beautiful, savage bird.” The spider blinked, and a single bloody tear trickled from his left eye. “She clawed away so many memories, leaving me with morsels of everything. Just enough to feel loss.”

“You’re suffering?”

“Yes.” He pulled on the oxygen once again. “I am.”

Good, I thought.

“She took my power, too. Much of my power.” He wiped his face. Smeared one of the tears. A pink smudge colored his cheek like rouge. “As you can see”—he indicated his weakened state—“I’m not the force I used to be. I’m like a car running on a single cylinder, or a battery at five percent power. As soon as I find her, I’m taking back what’s mine. And more besides.”

He was a monster to me. The thought of him with greater power was terrifying.

“I wouldn’t help you if I could,” I said.

“You have no say in the matter.”

I felt him scratching at my mind again. Mockingly. His eyes grew hazy and he cleared them with another blast of oxygen.

“I would kill you now,” he said. “Split your brain like a tomato.”

“Why don’t you?”

“You’re a link to the girl, however broken.” Another red tear curled from his eye. “You may be of use to me yet.”

I shook my ruined head and listened to the cold hiss of oxygen through the mask.

* * *

He attacked me again. A final scurry through my mind to ensure he’d left no stone unturned. I found energy enough to scream, and to vomit most of the water they’d given me. Then I drifted to the edge of consciousness, barely attached to who—where—I was, but feeling the spider’s plump body squeezing into my most secret places.

* * *

I felt devitalized, picked apart . . . as empty and faded as the casino at Asbury Park, with my glass shattered and the wind blowing through me. Eventually, I found the strength to gather the pieces of my brain—separated along their fissures, clogged with cobwebs—and slot them together with a watchmaker’s care.

I opened my eyes. The walls swam into focus first. Too close, too solid. Then I saw the spider, huddled in the wheelchair, his gray suit drooping off his withered frame, his face raglike beneath the oxygen mask.

One of the hunt dogs—his face a smudge—stepped toward me. The knife in his hand was small but sharp. I clenched my entire body, except for my jaw, which trembled.

“You might be tempted to go to the police,” he said blandly. “But consider, carefully, what you’ll tell them, and if they’ll believe you. And then look over your shoulder. We just might be there.”

He stepped behind me, cut my binds.

I spilled to the floor and stayed there for some time.

* * *

I lay in my hot stink as the pain in my head waned to a dull but constant thud. When I looked up, I saw that I was alone in the room. I cried and rolled onto my side. My ribs screamed and my spine fired off a series of explosive cracks.

Deep, burning breaths. Time ticked unevenly.

At length, I pushed myself to my knees, and then to my feet. I managed two agonizing steps before the door swung open.

The spider walked in.

I collapsed again.

* * *

He was stronger. Walked with a silver-tipped cane, but there was no wheelchair, no oxygen mask. His face, though, was the same gray color as the walls.

The thin smile had returned.

“Some people,” he said, “find the best way to remember something is to write it down. Others prefer repetition, visualization techniques, or mnemonics.”

I struggled to one knee and looked up at him, trying not to feel like a serf before his king.

“I find,” he said, “that creating associations is incredibly effective.”

He pulled the cluster of red feathers from his lapel, plucked one of them free, twirled it before my eyes.

“You won’t forget me . . . will you?”

I shook my head.

“No.” That feather was so red. “You won’t.”

I hated being on one knee, so I fought the pain and struggled to my feet. Our eyes came level. His were penetrating. Mine tear-struck and sore.

The feather followed me. He blew on it, and it bristled.

“I don’t think Sally Starling will contact you,” he said. “But if she does, you should alert me immediately. Likewise, if you happen upon information that may be of use, or uncover some deeply buried memory strand . . .”

Fuck you, I thought. I didn’t care if he read my mind.

“The pain. The threat,” he said, and his dark eyebrows took wing. “The humiliation. The violation. I’m sure you’ll do anything to avoid a repeat of what has happened here. Or something worse.”

The feather rolled between his thumb and forefinger, so bright it could burn.

“You’re on my radar now. If you try to run away, or even consider keeping information from me . . . I want you to look at this feather.”

He took my hand, placed it in my palm.

“This is how you’ll remember me.”

* * *

I kept the red feather. It’s a little worse for wear (we’ve had some adventures, that feather and I), but still bright and remarkable, each filament replete with the memory of what I endured.

Not that I needed association to help me remember. That particular ordeal runs deep—so deep that I don’t think even Sally could remove it from my brain. Some memories, for better or worse, touch the soul. That’s just the way it is.

It was the same with Sally. She was a part of me, occupying a place the spider could never reach, and it didn’t take me long to realize that I needed to find her. For the sake of my sanity, of course, but also because—as powerful as she was—I wanted to protect her. That may sound crazy, given what I went through, but hey . . . she was my girl. I knew this even though I couldn’t remember a damn thing about her.

So yeah, I kept the feather. Partly to remind me that bad things exist in the periphery, and that sometimes they can spill right in front of your eyes. But mostly to emphasize what Sally would go through if the spider and his hunt dogs ever caught up with her.

The pain. The threat. The humiliation. The violation.

I turned the feather from an ugly association to a symbol of justness and determination.

You’re on my radar now. If you try to run away, or even consider keeping information from me . . .

My old man was a Jedi Master when it came to bullshit, but he was right on the money when he said that there were too many supervillains in the world. I’d spent my whole life turning my back on confrontation. But not this time. I couldn’t—wouldn’t—let them win.

Not a coward, remember?

That red feather . . .

My tiny superhero cape.

MOMENT: BABY-BLUE SCHWINN

C