10,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

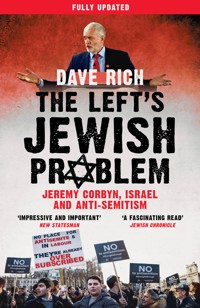

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

New, updated edition of an important and timely critique of Anti-Jewish sentiment on the left. There is a sickness at the heart of left-wing British politics, and in recent years it has silently spread, becoming ever more malignant. Today, it seems hard to believe that until the 1980s, the British left was broadly pro-Israel. And while Jeremy Corbyn's leadership may have thrown a harsher spotlight on the crisis, it is by no means a recent phenomenon. The widening gulf between British Jews and the anti-Israel left, now allying itself with Islamist extremists who demand Israel's destruction, did not happen overnight or by chance: political activists made it happen. This book reveals who they were, why they chose Palestine and how they sold their cause to the left. Based on new academic research, Dave Rich's nuanced and thoughtful guide brings fresh insight to an increasingly fraught debate. As the question becomes more urgent than ever, this new, fully updated edition, taking in events since 2016, provides an essential guide to the left's increasingly controversial 'Jewish problem'.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

‘Impressive and important … this powerful work should be read by everyone on the left.’

DAVID PATRIKARAKOS,NEW STATESMAN

‘A fascinating read.’

JEWISH CHRONICLE

‘How a party that was once proud of its anti-fascist traditions became the natural home for creeps, cranks and conspiracists is the subject of Dave Rich’s authoritative history of left antisemitism, which is all the more powerful for its moral and intellectual scrupulousness.’

NICK COHEN, THE OBSERVER

‘Essential reading for anyone seeking to understand modern British politics.’

STEPHEN POLLARD,DAILY EXPRESS

‘As a guide to a contemporary malady that is undermining the integrity of the left, Rich’s book is essential reading.’

BENJAMIN RAMM, JEWISH QUARTERLY

‘A remarkable, methodical documentation of the growth of left-wing anti-Semitism in Britain.’

JENNI FRAZER,TIMES OF ISRAEL

‘Thoroughly researched and penetrative analysis … This combination of academic research and practical involvement has enabled Rich to produce a detailed, informed, and incisive account of changes in left-wing thinking in the past sixty years, but particularly of the recent convulsions in the British Labour Party … Rich’s book is an important one that should be read by all those seeking to understand the New Left’s obsession with anti-Zionism and its inability to recognize, let alone deal with, its own antisemitism.’

LESLIE WAGNER, ISRAEL JOURNAL OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS

In memory of

Yoel Kohen Ülçer z”l

1 January 1984 – 15 November 2003

and

Dan Uzan z”l

2 June 1977 – 15 February 2015

Who gave their lives protecting their communities

CONTENTS

PREFACE TO THE NEW EDITION

In 2011, I began work on a history PhD about the growth of left-wing anti-Zionism in Britain from the 1960s until the 1980s and how it affected relations between Jews and the left. It looked mainly at a narrow part of left-wing politics over a relatively short period of time and, like most PhD theses, I assumed it would be of interest only to a limited audience. Yet, by the time I graduated in 2016, the subject of my research was no longer a matter of history and had returned to the front pages of Britain’s newspapers. The election of Jeremy Corbyn as Labour Party leader had, for one reason or another, made antisemitism and left-wing attitudes to Jews, Israel and Zionism a subject of national debate. It left me in the position of having something new to say about an old subject, and I set about converting my thesis into a political book explaining why this had happened. I expected it to have a short shelf-life: in the period between completing the first edition of this book at the end of June 2016 and its publication in early September of that year, most of the shadow Cabinet resigned, Labour MPs overwhelmingly backed a motion of no confidence in Corbyn and he was fighting a second leadership election in twelve months, having been forced to take legal action just to get onto the ballot paper. Yet, two years later, Corbyn is not only still leader of the Labour Party; his control of the party is stronger than ever, its problems with antisemitism have become more, not less, entrenched, and his relationship with the mainstream Jewish community in Britain ranges from non-existent to hostile. The day may still come when antisemitism can be left to historians, but for now, sadly, it seems as topical as ever.

This updated second edition tells the story of why this is the case. It has two new chapters covering the period from Corbyn’s election as Labour leader in September 2015 to Ken Livingstone’s resignation from the party in May 2018, in addition to the original six chapters of the first edition, which remain unchanged. Taken together, they explain the origin and growth of these political trends on the British left, where they came from, how they ended up in the Labour Party, and the impact they have had on Labour’s relations with British Jews. The early chapters draw on my original PhD thesis, but this book is quite different in both content and style and is hopefully more readable as a result. While my thesis ended in the 1980s, this book brings the story up to date, with new research covering the period since the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the war in Iraq and the profound change in the leadership and membership of the Labour Party.

When this book was first published in September 2016, I was grateful that most reviews were positive, but writing a second edition gives me the opportunity to consider criticisms that were made by some reviewers. One was that its primary focus should have been the alleged Israeli mistreatment of Palestinians and enduring occupation of Palestinian land, which, so these critics argued, is sufficient explanation of why relations between British Jews and the left have deteriorated so much. This misses the point: as I explain in the Introduction, this is not another book is about the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, but rather about attitudes and responses to that conflict on the British left that at times, however unwittingly, have incorporated or invigorated traditional antisemitic stereotypes and tropes. Another criticism was that I did not state whether I believe Jeremy Corbyn to be personally antisemitic, or whether anti-Zionism is invariably a form of antisemitism. The first question is one I address in the new material in this edition. On the second point, I argue throughout the book that while in theory a non-antisemitic form of anti-Zionism is possible and in the past has been quite common, in practice the dominant forms of anti-Zionism found on the left nowadays are usually antisemitic, whether by motivation, language or impact.

The most negative reviews and comments about this book came largely from anti-Zionist left-wing Jews. They paid it much more attention than any Palestinians did. It was as if they saw it as a threat to their own politics and to the position they have carved out for themselves as valued Jewish voices in parts of the left that are largely hostile to, or uninterested in, the concerns of the rest of the Jewish community. If that is the case, they will dislike this second edition even more than the first. The new chapters in this edition argue that Jewish anti-Zionists, in defending their own small patch of political ground, have done a great deal of damage to the left’s relations with the wider Jewish community. They are central to the story of Labour antisemitism under Corbyn’s leadership.

One challenge in writing about political history as it happens is that it can quickly go out of date, but, as this book explains, the political trends on the left that brought the problem of antisemitism into the Labour Party long predate Corbyn’s leadership and are unlikely to disappear any time soon. Corbyn’s rise is a symbol of the problem; whatever happens to him and his party in the near future, the issue of antisemitism on the left of British politics is unlikely to go away. Another challenge is that political language changes over time. In the 1960s and 1970s, large parts of the world were collectively described as the ‘Third World’. This generally included those parts of Africa, Asia and Latin America that had been colonised by European powers and were seeking and gaining independence during the post-war period. The term feels anachronistic and rather crass nowadays and has been superseded by ‘Global South’. Despite this, I have chosen to use ‘Third World’ where appropriate in this book, mainly for consistency. At that time there was a form of left-wing internationalism known as ‘Third Worldism’ that championed the rights and interests of those countries. It plays an important role in this book and had no other name. However, I appreciate the term may jar for some readers, for which I apologise.

The other problem with writing about left-wing politics is that the smaller groups on the Marxist and Trotskyist left have a habit of splitting and creating new groups, or just changing their own names, every few years. I have tried to follow and explain these changes as simply as possible whenever it is essential to do so, without overcomplicating the story. I expect some devotees of political esotericism may feel I have been too loose with my organisational attributions at different points in the text, but this book is not supposed to be a catalogue of British Marxism. It is an explanation of the different ideas and ways of thinking about Jews, Israel and Zionism that circulate on the British left. As such, the precise divisions between the left’s component parts are less relevant.

There are several people who supported me throughout my academic research and who helped me turn it into this book. The Community Security Trust funded my studies and, as my employer, allowed me the time to pursue my research alongside my regular work. I particularly value Mark Gardner’s support, advice and friendship over many years. Professor David Feldman at the Pears Institute for the Study of Antisemitism, Birkbeck, University of London, has been a source of wisdom and good humour during and since my studies. Dean Godson, Andrew Roberts and Robert Hardman helped to plot the path from academic to political writing. Philip Spencer offered some astute observations on one of my chapters. Simon Gallant’s legal advice was as reassuring as ever. Mike Day at the National Union of Students and Martin Frey at the Board of Deputies of British Jews facilitated access to the archives of those two organisations.

Many of the people who were involved in the events described in my thesis, and in this book, volunteered their time so that I could interview them for my research. Some extended their assistance further by providing me with documents or putting me in contact with other potential interviewees. It would be impractical to list all of them and unfair to single any out, not least because some asked to remain anonymous: I am indebted to each and every one for the thoughts, memories and opinions they shared with me. Since the first edition of this book was published there have been several other people in the Labour Party, Jewish and not, who have shared their experiences of antisemitism with me. I am especially grateful to them.

The idea for my PhD thesis, and some of its preliminary research, originated in a chapter I contributed to Antisemitism on the Campus: Past and Present (Boston: Academic Studies Press, 2011), edited by Eunice G. Pollack. I am grateful to Eunice for giving me that original opportunity and for granting permission to reuse some of the research in this book. Iain Dale, James Stephens, Olivia Beattie and all their colleagues at Biteback Publishing have been a pleasure to work with and I appreciate all they have done in making both editions of this book a reality.

Finally, I owe the biggest debt of all at home to Miriam and our children, who put up with this project intruding on our family life for years and who supported me throughout. When I finished the first edition, our children made me promise I would never write another book. Writing a second edition keeps the letter of that promise but, I concede, not its spirit. They have been very forgiving; my love and gratitude for them is limitless.

INTRODUCTION TO THE NEW EDITION

‘Tomorrow evening it will be my pleasure and my honour to host an event in Parliament where our friends from Hezbollah will be speaking. I’ve also invited friends from Hamas to come and speak as well … the idea that an organisation that is dedicated towards the good of the Palestinian people and bringing about long-term peace and social justice and political justice in the whole region should be labelled as a terrorist organisation by the British government is really a big, big historical mistake.’

JEREMY CORBYN, LONDON, 30 MARCH 2009

‘The JC rarely claims to speak for anyone other than ourselves. We are just a newspaper. But in this rare instance we are certain that we speak for the vast majority of British Jews in expressing deep foreboding at the prospect of Mr Corbyn’s election as Labour leader … If Mr Corbyn is not to be regarded from the day of his election as an enemy of Britain’s Jewish community, he has a number of questions which he must answer in full and immediately.’

JEWISH CHRONICLE EDITORIAL, 12 AUGUST 2015

Since 2016, antisemitism has become a national political issue in Britain for the first time in decades. Stories about antisemitism lead the news and it is the subject of sharp exchanges in Parliament. This hasn’t come about because of a surge in support for neo-Nazism or a spate of jihadist terrorism against Jews. It has happened because of a crisis in Britain’s party of the left, a party that defines itself by its opposition to racism and which has enjoyed Jewish support for most of its history. Antisemitism is a headline story because of the Labour Party. It is important to acknowledge just how strange this is. The left has always seen itself as a movement that opposes antisemitism, opposes fascism and defends Jews and other minorities from bigotry and prejudice. This is a proud history that has always attracted Jewish support. Yet, in the first six months of 2016, the Labour Party felt the need to hold three different inquiries into antisemitism and found itself abandoned by Jewish voters. In March 2018, the leadership bodies of the British Jewish community took the extraordinary and unprecedented step of holding a demonstration outside Parliament to protest about antisemitism in Labour. The decline in the relationship between the Labour Party and Britain’s Jewish community has intensified since Jeremy Corbyn’s election as Labour Party leader, but it is fuelled by trends on the wider left that have been building for many years. There are socio-economic reasons for the long-term drift of Jewish voters from Labour to the Conservatives, but these reasons alone do not explain the scale of the change, nor its recent acceleration. A long-standing supporter of the Palestinians and opponent of Israel, Corbyn came into post facing a list of questions about alleged associations with people accused of Holocaust denial, antisemitism and terrorism. Beyond these immediate questions about Corbyn’s personal associations and views, his rise to the Labour leadership personifies a widespread left-wing hostility to Israel that alienates many Jews. It is symbolic that while the last two Labour Prime Ministers, Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, were both patrons of the Jewish National Fund (an Israeli body that was instrumental in buying land for the new Jewish state before and after its independence in 1948), Corbyn is patron of the Palestine Solidarity Campaign. However, this is not just a story about the left’s disenchantment with Israel. It is also a story about the growth of antisemitism on the left, the failure of many on the left to recognise and oppose antisemitism when it appears, and the extent to which people on the left and in the Labour Party even endorse and express antisemitic attitudes themselves.

Most British Jews feel a personal, emotional or spiritual connection to Israel. Most have visited the country and have family and friends there. According to a 2010 survey by the Institute for Jewish Policy Research, 95 per cent of British Jews said Israel plays some role in their Jewish identity, 82 per cent said it plays a central or important role and 90 per cent said they see Israel as the ancestral homeland of the Jewish people. A similar survey by City University London in 2015 found that 90 per cent of British Jews support Israel’s right to exist as a Jewish state, while 93 per cent said it plays a role in their Jewish identity. For most Jews, this is what Zionism is: the idea that the Jews are a people whose homeland is Israel (wherever they actually live); that the Jewish people have the right to a state; and that Israel’s existence is an important part of what it means to be Jewish today. This deep, instinctive bond doesn’t necessarily translate into political support for Israeli governments or their policies: both surveys found strong support for a two-state solution and opposition to expansion of Jewish settlements in the West Bank. For many Jews, their relationship to Israel is not a political statement at all. The idea that Israel shouldn’t exist, or that Zionism – the political movement that created Israel – was a racist, colonial endeavour rather than a legitimate expression of Jewish nationhood, cuts to the heart of British Jews’ sense of who they are. Whether it is in arts, culture, education, religion, politics or cuisine, Israel is at the heart of global Jewish life, and British Jews are part of that world.

Meanwhile, sympathy for the Palestinians and opposition to Israel has become the default position for many on the left: a defining marker of what it means to be progressive. Find out what somebody on the left thinks about Israel and Zionism and you can usually divine their positions on terrorism, Islamist extremism, military interventions overseas and the historic wisdom of allying Britain to American power. Many who oppose Israel blame it for, amongst other things, the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the grievances that lead to jihadist terrorism, and the growth of prejudice towards Muslims in North America and Western Europe. The Israeli–Palestinian conflict has come to symbolise much more than a struggle between two peoples for the same small strip of land on the eastern Mediterranean. It is the epitome of Western domination, racism and colonialism, and the Palestinians have come to represent all victims of Western power and militarism. ‘In our thousands, in our millions, we are all Palestinians,’ Corbyn told a rally in 2010. Or, as Seumas Milne – then a Guardian journalist, now Labour’s executive director of strategy and communications – put it, Palestine has become ‘the great international cause of our time’.

One way to appreciate the gulf that has opened up between British Jews and Corbyn’s part of the left came via two significant anniversaries in 2017. That year marked fifty years since the Six Day War, when Israel defeated the combined armed forces of its Arab neighbours, swept through the Sinai Peninsula, the Golan Heights, the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, and began its military rule over the Palestinian population of the latter territory that continues to this day. It was also the centenary of what many consider to be the starting gun for the entire conflict: the Balfour Declaration, when the British government promised to ‘view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people’, and to ‘use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object’. Whether someone considered these to be anniversaries worthy of celebration or occasions for deep remorse depends on where their political sympathies lie. The Balfour Declaration either began the process of redemption of the Jewish people via the sovereignty of national independence, or it was an act of immense colonial dispossession and betrayal of the Palestinians by Britain. The Six Day War was either a miraculous military victory that ensured the survival of the young Jewish state, or a campaign of aggressive conquest that began the occupation of Palestinian territory that has endured for half a century. Jeremy Corbyn has made his view of both clear. The Balfour Declaration, he wrote in 2008,

became an iconic symbol for the Zionist movement and led to the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948 and the expulsion of Palestinians … Britain’s history of colonial interference in the region during the dying days of the Ottoman Empire and its role as the mandate power from the end of the First World War to 1948 leaves it with much to answer for.

Corbyn turned down an invitation to attend an official dinner in London to celebrate the centenary of the Balfour Declaration in November 2017, sending shadow Foreign Secretary Emily Thornberry in his place. As for the Six Day War, it is one of several events in the history of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict that Corbyn once included in what he called ‘the macabre list of inhumanity’ inflicted by Israel on the Palestinians since Israel’s creation.

Britain has played an important role in this history and continues to do so. The Balfour Declaration was issued by the British government in part due to the activism of a group of Zionists in Manchester that included Chaim Weizmann, who went on to become Israel’s first President. Britain was the colonial power in Palestine from 1922 until Israel’s creation in 1948 and the influence of this period can still be felt in Israel. Yet, by the 1980s, according to historian Colin Shindler, London had become ‘the European centre of opposition to Israel’s policies – and in a growing number of cases opposition to Israel as a nation-state’. British left-wing anti-Zionism grew out of international networks and continues to have global resonance. In 2010, the Reut Institute in Israel, a think tank that undertook a large research project into anti-Israel political activism, argued that London’s role as a centre for international media, NGOs, academia and culture, all operating in the English language, made it ‘a leading hub of delegitimization [of Israel] with significant global influence’. Furthermore, Reut claimed, ‘London is the capital of the One-State idea – the concept of the One-State Solution is discussed and advanced in London more than anywhere else, and disseminated throughout the world.’ What happens in Britain, and on the British left, matters well beyond its shores.

Disagreements over where the boundaries lie between antisemitism, anti-Zionism and criticism of Israel underpin much of this problem. This is not just a disagreement about Israel and Palestine. There are also profound differences about what antisemitism is, where it is found and how it manifests. This book is an effort to explain how and why antisemitism appears on the left, and an appeal to the left to recognise and expel antisemitism from its politics. It is a truism that criticism of Israel – even harsh or inaccurate criticism – does not constitute antisemitism. This book is not intended to be a defence of Israel or an objection to criticisms of its behaviour. Criticisms of Israeli policies and practices that use the same kind of language used to criticise similar policies and practices of other governments are highly unlikely to be antisemitic. This language might involve discussion of human rights, or inequality and discrimination, or occupation and war crimes. Criticisms of Israel become suspect when they use language and ideas that draw on older antisemitic myths about Jews. These may include conspiracy theories about Jewish wealth and secret influence, or nods to the medieval ‘blood libel’ allegation that bloodthirsty Jews delight in killing children. Alarm bells should ring if Israel’s Jewish character is enlisted as an explanation for its alleged wrongdoing. Comparisons of Israel to Nazi Germany are a new and insidious form of antisemitism, which exploit the lasting pain of the Holocaust – the Jewish people’s greatest modern trauma – to attack the world’s only Jewish state. However, normal political criticisms of Israeli policies, or sympathy and support for Palestinian rights, are not antisemitic, and, crucially, they are not anti-Zionist either. If Zionism is simply the belief that the Jews are a people deserving of a state and that Israel is that dream made real, this allows for a wide range of views about what the policies, citizenship and borders of Israel should be. It is possible to be a Zionist, to criticise Israeli policies and to support Palestinian statehood, all at the same time – and many people, Jewish and not, do all three with no contradiction at all.

Just to confuse matters further, there are different types of anti-Zionism. In its basic form, anti-Zionism is an ideological position based on the belief that the State of Israel should not exist and, for some, denial of the very concept of Jewish peoplehood. When political Zionism first emerged in the late nineteenth century to call for the creation of a Jewish home in what is now Israel, many Jews rejected it as an unrealistic and dangerous proposal. Orthodox Jews had theological reasons to oppose the creation of a secular Jewish state. More assimilated, secular Jews in the Diaspora feared that Zionism endangered their status because it might encourage their non-Jewish fellow citizens to view them as belonging to an alien nation, rather than being loyal to the countries of their birth. Marxists argued that Jews should seek emancipation via socialist revolution rather than through their own national movement. Over time Zionism won the struggle for the loyalty of most Jews, largely due to the cataclysmic shock of the Holocaust and the redemptive hope found in the creation of Israel, and it is now by far the dominant view amongst Jewish people worldwide; but that does not mean the argument is over. Jewish anti-Zionists continue to pursue their own brand of Jewish politics, but, having lost the ability to appeal to the mass of Jews, instead seek support and solidarity from Israel’s other opponents – some of whom are motivated by more sinister instincts. In addition, from the 1950s onwards, the Soviet Union developed a line in overtly antisemitic anti-Zionism that portrays Zionism as a global conspiracy with Israel as its tool, powered by the wealth of Jewish capitalists and responsible for war and economic exploitation. This antisemitic anti-Zionism has little to do with how Jews define Zionism and employs strikingly similar language to that used by antisemites when they defame Jews. It can now be found in far-right, Islamist and far-left circles. Its appeal to these different political extremes is a testament to the power and durability of conspiracy theories, especially when they involve the conspiracy theorists’ favourite demon: the Jews. The pro-Palestinian movement in Britain includes anti-Zionists who object to Israel’s existence through reasoned argument, those who do so as part of a conspiracy theory of global Zionist domination, and critics of Israel who want to see a Palestinian state created alongside, rather than instead of, Israel.

These differences can sometimes feel quite academic and unrelated to the practical realities of how left-wing attitudes to Israel and Zionism actually work. Whenever violence flares between Israel and Hamas in Gaza, or with Hezbollah in Lebanon, tens of thousands of people march through the streets of British cities in protest. Left-wing leaders and commentators condemn Israel’s actions, often accusing it of committing massacres or even genocide. Jeremy Corbyn, before he became Labour leader, would usually be found at the head of the march or speaking from the platform at these demonstrations. The issue generates more anger and activism on the left than any other overseas conflict. This anger and intense focus on Israel makes many Jews feel uneasy. It doesn’t help that whenever such wars take place, the amount of antisemitic hate crime recorded in Britain usually goes up. Yet, just next door to Israel, the number of people killed in the Syrian civil war dwarfs the total number of dead in all of Israel’s conflicts. There are no large left-wing demonstrations in Britain to protest against massacres of Syrians by its own government. Nobody chants: ‘In our thousands, in our millions, we are all Syrians.’ This begs the question: why Israel?

There are various simplistic answers to this question, none of which are satisfactory. Israel’s opponents would say that Israel, quite simply, is one of the worst human rights abusers on earth and is a uniquely racist, violent and oppressive state. Even worse, it does all of this as a Western ally. According to this view, the reason that the left opposes Israel is because of what Israel does, and because of the West’s complicity as Israel’s political backer and armourer. There are a few problems with this explanation. Firstly, people on the left have viewed the same events in radically different ways at different times in Israel’s seventy-year history. For example, Israel’s creation in 1948 was once viewed by most of the British left as a necessary and welcome act; now it is lamented by many as a dreadful mistake. These shifts have as much to do with political changes in the British left over that period as with the nature of those events themselves. Secondly, criticism of what Israel does often becomes criticism of what Israel is – and from there to an argument that it shouldn’t have been created and shouldn’t continue to exist in the future. Thirdly, there are other countries, also closely allied to the West, whose human rights abuses do not provoke anything like the same reaction from the British left. Turkey is a NATO ally and has been occupying the territory of an EU member state in Cyprus for almost as long as Israel has occupied the West Bank. It buys substantially more arms from Britain than Israel does. Its conflict with its Kurdish minority over many years has involved terrorism, heavy loss of life, repression of Kurdish national identity and restrictions of basic freedoms, yet this elicits little activism from the British left.

Another simplistic explanation is that the left’s hostility to Israel is nothing other than a modern expression of the same old antisemitism that Jews have faced for centuries. According to this argument, Israel is the world’s only Jewish state and the left’s disproportionate focus on its behaviour is a modern reenactment of Europe’s long history of anti-Jewish prejudice. Instead of persecuting individual Jews, now it is Israel that is always held to a higher standard and never forgiven for its (real and imagined) wrongdoing. This also fails to pass muster. Sympathy for the Palestinians and opposition to Israeli policies needn’t involve antisemitism. Many of Israel’s left-wing critics do not oppose its existence and would support a two-state solution to the conflict. The criticisms of Israeli policies found on the British left are also heard within Israel – indeed, many of them originate there. Most of Israel’s left-wing critics are avowedly anti-racist and explicitly opposed to antisemitism. Many are Jews and say they act in the name of what they believe to be Jewish values. Even if these promises to oppose antisemitism remain unfulfilled and the mobilisation of Jewish identity to criticise Israel is cynically done, this still makes opposition to Israel different from the antisemitism that affected European Jewry in past centuries. Antisemitism does play a role in this story, but for the most part it does not involve people who are consciously antisemitic. Rather, it is a problem of antisemitic ideas and ways of thinking about Jews, Zionism and Israel that have spread, mostly unwittingly and often unchallenged, in what is supposed to be an anti-racist movement. It is possible to believe antisemitic stereotypes about Jews while not feeling any visceral hostility towards them and to still think of yourself as an anti-racist. This apparently contradictory phenomenon is found across British society. In September 2017, the largest ever opinion survey of British attitudes towards Jews and Israel was published by the Institute for Jewish Policy Research and the Community Security Trust (full disclosure: I worked on this project for CST). It found that only a small proportion of people in Britain are consciously antisemitic (between 3 and 10 per cent, depending on how the question is asked), but 30 per cent believe at least one negative stereotype or attitude about Jews. In other words, antisemitic attitudes are much more common than antisemitic people. This survey also found that the more anti-Israel a person is, the more likely they are to have antisemitic attitudes: 74 per cent of people with strongly anti-Israel views held at least one antisemitic viewpoint, compared to 30 per cent of the general population. Yet the same survey found other people who are just as strongly anti-Israel but have no antisemitic attitudes at all. This all suggests that the relationship between antisemitism, opposition to Israel and anti-Zionism is complex and differs from individual to individual. For some, anti-Israel activism is a socially acceptable way to express their anti-Jewish prejudice; for others, it is simply another political issue to campaign on and has nothing to do with antisemitism at all.

This book is an attempt to answer this question in a different way, by looking at how these ideas first emerged and have spread through activist groups and networks, from grassroots campaigners into the Labour Party; and how they have informed the thinking of Britain’s left and Corbyn’s Labour Party on the subject. This inevitably means that some parts of the left are given more attention than others in these pages. This book does not include a complete history of Labour Party Middle East policy, for example, or every twist and turn of Britain’s myriad Marxist and Trotskyist organisations. These do feature in this book, but only when they are relevant to the main story. This book is also not about the Israeli–Palestinian conflict itself. There are already plenty of books that tell the histories of Israel’s creation, Palestinian and Jewish refugees, wars, terrorism, occupation, current politics and colonial legacies. They are written from a variety of viewpoints, some more obviously politicised than others. That history and the ongoing conflict provide the backdrop to this book, but they aren’t its subject. Nor does this book look in detail at the appeal of the Conservative Party to British Jews and the broader socioeconomic reasons why many Jewish voters have drifted rightwards since the 1980s. This book is specifically about the British left: how people on the left have tried to make sense of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, why the political ideas and campaigns they came up with in response to it have sometimes involved antisemitic methods, language and ideas, and how this explains the problem of antisemitism in today’s Labour Party.

To understand how Israel, of all the countries and conflicts in the world, has come to be a touchstone issue for the left, it is necessary to go back to the beginning. How did this left-wing anti-Zionism begin, what are its founding values and influences and what is its political vision? This change didn’t happen by chance. It took activists, organisations and ideas to make it happen. To find an answer, this book begins by shining its light mainly at what was called the New Left – the 1960s, radical, youthful left – that played a decisive role in flipping left-wing opinion from being overwhelmingly pro-Israel to its current pro-Palestinian consensus. This political world was the seedbed for the ideas and activist groups that created the kind of left-wing anti-Zionism that is familiar today. The allegations that Israel is a product of Western colonialism, that Zionism is a racist ideology, and that both deserve the same opprobrium previously directed at apartheid South Africa came from that world. It is the part of the left that explains the politics of Jeremy Corbyn, Ken Livingstone, George Galloway, the Stop the War Coalition, the Palestine Solidarity Campaign and similar groups and people. Our story begins in the 1960s, a decade when left-wing attitudes to everything – including Israel – were turned upside down.

CHAPTER ONE

WHEN THE LEFT STOPPED LOVING ISRAEL

However permanent it feels today, the idea that being on the left means being opposed to Israel and Zionism is, politically speaking, a relatively recent development. It is true that opposition to Israeli policies, sympathy for the Palestinian cause and to a lesser extent outright anti-Zionism are now commonplace, although not unchallenged, across all parts of the British left. However, this only began to take shape in the 1960s, when some New Left thinkers and movements in Europe and North America came to view Israel as a part of Western colonialism rather than a progressive expression of Jewish nationhood. Having emerged on the radical fringes, this central idea gained momentum in the 1970s and burst into mainstream left-wing thinking in the 1980s. Prior to this development, left-wing opinion was broadly sympathetic to Israel and the political movement that founded it – Zionism – for most of the twentieth century, while left-wing parties and organisations attracted the support of many Jews.

The creation of the State of Israel in 1948 enjoyed the support of the Soviet Union and was welcomed across the British left. Israel was created by Jews from within the European left tradition, so most European leftists saw Zionism as a socialist project worthy of support. It was born out of a violent insurgency against the British forces that occupied Palestine under a United Nations mandate from 1922 to 1948. This insurgency during the final years of the British mandate period gave Zionism grounds to claim an anti-colonial aspect, which helped attract Soviet approval. In the years immediately following the Second World War, Stalin sought to weaken and divide the Western imperial powers, and this Zionist insurgency represented the strongest active threat to the British presence in the region. In contrast, much of the Arab leadership at that time comprised monarchies and hereditary sheikhdoms that were hostile to communism.

Soviet support for Israel came in weapons and votes. When the United Nations proposed in November 1947 to divide Palestine into two states, one Jewish and one Arab (with Jerusalem under international administration), the Soviet bloc at the UN supported the plan, effectively voting in favour of the creation of a Jewish state. The weapons came from Czechoslovakia, which was a vital source of arms and aircraft for Israel in 1947 and 1948. Shortly after five Arab armies had invaded their new Jewish neighbour in May 1948, the Soviet representative at the United Nations, Andrei Gromyko, criticised them for trying to suppress ‘the national liberation movement in Palestine’ – a striking choice of words, given that so much left-wing opposition to Israel today is based on the idea that Zionism is a product of Western colonialism rather than a liberation movement against it. However, Soviet backing for Israel was always more pragmatic than ideological and turned out to be both superficial and temporary. It began to ebb as early as mid-1948 and the arms supplies came to a complete halt the following year. The two countries broke off diplomatic relations for a short period in 1953 following a series of antisemitic show trials in the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia. In 1955, Egypt signed its own arms deal with Czechoslovakia, becoming a client state of the Soviet bloc, and relations between Israel and the Soviet Union were hostile thereafter.1

Significantly, even when the Soviet Union gave diplomatic backing to Israel in 1947 and 1948, it never endorsed Zionism as an ideology. Soviet support for Israel was based on sound foreign policy reasons but the thought it might lead to support for Zionism amongst Soviet Jews alarmed the Soviet authorities. Their fears crystallised when thousands turned out to welcome the new Israeli ambassador, Golda Meyerson (who later became Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir), at Moscow’s Grand Synagogue for the festival of Yom Kippur in 1948. A predictable crackdown on Jewish cultural and political activity in the Soviet Union followed. Official Soviet policy had always disapproved of Zionism as a bourgeois political movement amongst Soviet Jews, even while helping the Zionist movement to achieve its ultimate goal of a Jewish state. Thus, when Gromyko and others explained their support for the partition of Palestine in 1947, they spoke only of the ‘Jewish people’ or the ‘Jewish population’ in Palestine, thereby observing a careful but crucial distinction between the national rights of Jews living in Palestine, and Zionism as an ideology or political movement. It was an important choice of words, given the historic (and future) hostility of Marxist–Leninism to Zionism, and the conspiratorial role Zionism was accorded in post-war antisemitic propaganda spread by the Soviet Union and its satellite states in Eastern Europe. Nevertheless, support for Israel in 1948 brought the USSR into line, at least temporarily, with the political sympathies of the wider British left, where admiration for Zionist efforts to build a new society in Palestine along socialist lines merged with sympathy at the plight of Holocaust survivors marooned in post-war Europe, and pragmatic recognition that nowhere other than the new Jewish state was willing to take in large numbers of Jewish refugees.

The Labour Party consistently supported the creation of a Jewish national home in Palestine from the Balfour Declaration of 1917 until the end of the Second World War. The socialist Zionist organisation Poale Zion affiliated to the Labour Party in 1920 and in 1944 the party even endorsed a proposal to transfer Arabs out of Palestine to make way for Jewish immigration. This enthusiasm was tempered by Labour’s post-war Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin, who was more sympathetic to Arab claims on Palestine and feared that a socialist Israel might be pro-Soviet. He also had a habit of making antisemitic remarks about Jews. Under Bevin’s watch, Britain abstained in the 1947 UN vote to partition Palestine, but generally speaking the ties between the Labour Party and Israel remained overwhelmingly friendly and supportive. There were strong links between the British and Israeli Labour Parties, both directly and as sister parties in the Socialist International. Labour Friends of Israel was formed in 1957 and at the time of the Six Day War, support for Israel remained consistent throughout the parliamentary party, constituency Labour parties and the trade union movement. During the 1960s, the TUC gave funding to its Israeli equivalent, the Histadrut, to train African trade unionists at its Afro-Asian Institute in Tel Aviv. Even Tribune, the newspaper of the Labour left, was firmly pro-Israel until the 1960s. ‘The cause of Israel is the cause of democratic Socialism,’ it wrote in 1955.2

This relationship between Jews and the left worked both ways: Jews were found in disproportionately large numbers in Socialist, Social Democratic and Communist parties across Europe and North America in the latter part of the nineteenth and early to mid-twentieth centuries. It is estimated that in the late 1940s and early 1950s, 10 per cent of activists in the Communist Party of Great Britain were Jewish, when Jews formed less than 1 per cent of the UK population. For much of this time, Jews and the left were intimately involved in each other’s stories. Australian academic Philip Mendes went so far as to claim: ‘It can, in fact, be argued that from approximately 1830 until 1970, an informal political alliance existed between Jews and the political left.’ If this is perhaps stretching things too far, it does attest to the familiarity between the left and European Jews in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. ‘The history of the socialist movement since the 1930s’, Belgian Trotskyist Nathan Weinstock wrote in 1969, ‘shows that many of the decisive issues the working class has had to face have involved the Jewish question.’3

This all began to change in the 1960s. The Six Day War of June 1967 was greeted by an outburst of radical left-wing criticism of Israel, although – as we shall see – the roots of this critique were visible before that date. By the end of the decade, Britain’s radical New Left had begun to actively campaign for Palestine, and in the 1970s the first grassroots activist groups dedicated specifically to the Palestinian cause were launched. This swelling support for Palestine started to have an impact on Labour Party policy in the 1980s, a decade when relations between the party and British Jews began to noticeably sour. Since then, the view that emerged from the New Left of Israel as a colonial, militaristic and racist state preventing the Palestinians from achieving self-determination has spread widely across the left in general. It is easy to overstate the extent of this change. Israel retains support within the Labour Party, notably from its last two Prime Ministers. However, opposition to (at the very least) aspects of Israeli policies in relation to the West Bank and Gaza Strip, and sympathy for the Palestinian national cause, now dominate British left-wing opinion on the subject, while anti-Zionism is axiomatic for much of the Marxist left.

To understand these changes, it is necessary first of all to appreciate how the left as a whole changed during that period. The New Left that formed in Britain in the 1950s and 1960s was quite different from the Old Left of trade unions, Communist Party branches and – ironically, given its current leadership – the Labour Party. The world that had defined the left since the 1880s, in which socialist labour movements, in both trade union and parliamentary forms, campaigned for the rights of working-class communities formed by mass industrialisation, was beginning to crumble by the 1950s. Its political foundations were increasingly eroded on one side by rising post-war prosperity across Western societies, and on the other by radical, left-wing causes that did not fit within the old class politics. Society was changing in other ways, too. The combination of the post-war population boom and sustained economic growth in Western Europe in the 1950s created a new phenomenon of young people with money to spend, who would provide the foot soldiers of the 1960s New Left.

This new political generation was marked by a lack of deference for authority and an organisational fluidity that spawned a bewildering array of single-issue pressure groups and campaigns. The old left-wing politics of mass labour mobilisation and class struggle were directly challenged, and at times replaced, by race, gender, sexuality, peace and the environment as the causes that shaped the New Left and continue to animate many left-wing activists today. It has spawned many well-known campaign groups: from the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and the Anti-Apartheid Movement in the 1960s, to the Stop the War Coalition and the Palestine Solidarity Campaign today. As New Left superseded Old, so identity politics replaced class politics as its primary mobilising idea. It was all very different from the Old Left that was forged in the hardships of the 1930s and the sacrifice of the wartime struggle against fascism. Instead, the New Left effectively represented a new social class, rooted in intellectual and cultural professions, populated by public sector workers, and whose political agenda would come to be dominated by identity and iconoclasm. It is no coincidence that anti-Israel sentiment and activism is prominent in the cultural, intellectual and academic parts of modern Britain, given that these are precisely the sectors where New Left politics has always found the greatest support.

As well as a new set of political ideas, the New Left also represented a new political attitude. While the 1950s New Left in Britain had been largely an intellectual movement, the 1968 version was much more activist, militant and confrontational. It forced its way into the national consciousness with large (and sometimes violent) demonstrations in central London against the Vietnam War. Direct action tactics, sit-ins and cultural change were as much a part of the New Left as marches and rallies, while it was the beginning of a connection between youth culture and political radicalism that remains to this day. Britain saw a wave of protests at university campuses in the late 1960s, while France experienced a much larger student insurrection against the state itself.

There is, admittedly, an element of mythology about all of this. While many of those who were present like to think that they were part of a global uprising of revolutionary youth, the reality was often rather more mundane. In Britain, most student protests related to parochial issues like night-time curfews, dress codes and exclusion from university decision-making bodies rather than more glamorous international campaigns. Shirley Williams, who was Minister of State with responsibility for higher education at the time, felt that ‘the student revolution was pretty artificial … it was exciting all right, but pointless’. Nevertheless, student protests were part of a wider erosion of deference to generational authority, both within the left and in society as a whole. By the late 1960s, the split between Old and New Left was as much a case of mutual incomprehension across generations as any kind of political schism. The Old Left, defined by its collective ethos and economic deprivations, had little time for the student left, with its sense of individualism, cultural experimentation and consumer aspirations.4

The New Left is Jeremy Corbyn’s political home. Born shortly after the war, he joined the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in the early 1960s, demonstrated against the Vietnam War in the late 1960s and did voluntary work in post-colonial Jamaica before travelling around Latin America. He is a patron of the Palestine Solidarity Campaign and has been chair of the Stop the War Coalition for most of its existence. Coming from a relatively comfortable background and working for two trade unions before becoming a Labour MP, Corbyn is a typical product of the 1960s New Left. His journey to the Labour Party leadership symbolises the New Left’s gradual reshaping of the cultural sensibilities of left-wing politics: the ultimate New Left triumph, rather than a return to Old Labour. The disregard for NATO shown by Corbyn, Ken Livingstone and others on the left of the Labour Party fits perfectly with this New Left tradition and highlights how much it is a departure from Labour’s own history. Corbyn has criticised NATO for expanding into Eastern Europe and said that it should have been wound up in 1990, at the end of the Cold War. Livingstone has questioned whether Britain should remain a member. Yet NATO owes its existence in large part to the same Labour government that created the National Health Service. It was a Labour Foreign Secretary, Ernest Bevin, who insisted that a post-war West European defence pact required American involvement. Efforts to rebuild a shattered Europe along social democratic lines would only succeed, so the thinking went, if further Soviet expansion could be deterred. But while Labour’s creation of the NHS has become a sacred part of the left’s own history, NATO is viewed with suspicion as a manifestation of American militarism.

Anti-Zionism and hostility to Israel are also part of this New Left worldview. The idea that Zionism is a racist, colonialist ideology, and Israel an illegitimate remnant of Western colonialism in the Middle East, came directly from the New Left of the 1960s. Anti-colonialism, race and the Cold War were formative in the New Left’s development and created a framework that left Israel and Zionism on the wrong side of its political thinking. The British New Left was born in November 1956, when the Hungarian and Suez crises occurred in the same week. In Hungary, an uprising of students and workers demanding democratic freedoms and an end to Soviet domination was crushed by a Soviet invasion. Meanwhile, Britain, France and Israel secretly arranged a three-pronged invasion of Egypt that would allow Britain and France to seize the Suez Canal that had been nationalised by Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser in July. The day after Soviet forces attacked Budapest, British and French troops landed in Egypt, ostensibly as a peacekeeping move in response to the Israeli invasion of the Sinai Peninsula the week before, but in fact to seize control of the Suez Canal. The cynicism and violence of events in Hungary and Egypt, with Communism and the Western democracies both involved, caused huge disillusionment across the left. Communist parties across Europe had already been shaken that year by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev’s ‘secret speech’ to the 20th Congress of the Soviet Communist Party, in which he denounced crimes committed under Stalin’s leadership. Some 10,000 members left the Communist Party of Great Britain in protest at its support for the Soviet invasion, most of whom also departed organised Marxist politics for good. Many sought a new type of left-wing politics with an independent position beyond the two Cold War blocs, combining opposition to Western imperialism with freedom from the ideological constraints demanded by Stalinism. A series of dissenting publications emerged from academic and intellectual circles inside and outside the Communist Party, the most important of which, the New Left Review, was launched in 1960 and remains the house journal of the intellectual left in Britain today.

These crises, and the formation of the New Left, happened against a political backdrop in which decolonisation and race were increasingly prominent and urgent issues. The Algerian war of independence had begun in 1954, the same year in which Labour MP Fenner Brockway founded the Movement for Colonial Freedom; 1955 saw the first Afro-Asian Conference in Bandung, where a bloc of newly independent, post-colonial states began to take shape; and in May 1956 Ghana became the first black African nation to gain independence from Britain. The Anti-Apartheid Movement was formed in London in 1960 and would go on to be the most successful of all New Left single-issue campaigns. The civil rights movement in America and the impact of commonwealth immigration to Britain in the 1950s and 1960s added to the sense that race would play an increasingly pivotal role in both domestic and foreign affairs. Anti-colonialism began as a campaign for European colonies to gain their independence, and morphed into a general political support for those new states after they had become independent. The sheer scale of change as decolonisation gathered pace and European empires were dismantled was reflected in the membership of the United Nations, which grew from fifty-one members at its formation in 1945 to ninety-nine members by 1960 and 142 by 1975. The new states that emerged from this process formed an ostensibly neutral bloc in international relations that was formalised into the Non-Aligned Movement at successive conferences in Cairo and Belgrade in 1961. As might be inferred from these two locations, although the Non-Aligned Movement was theoretically neutral in the Cold War, it was usually more closely aligned with Soviet interests than with Western ones. It provided fertile soil for the idea, now commonplace on the mainstream left, that Zionism is a European colonial movement and Israel is a bastion of white European settlers rather than a legitimate nation state in its own right. This is the basic intellectual and political framework through which Zionism and Israel are explained in New Left politics. It didn’t happen by chance, and its development was a product of the radical anti-colonial politics of the 1960s.

This was a decade when some on the left gave up on the revolutionary potential of the Western working class and looked overseas for radical inspiration. By this way of thinking, the bloc of post-colonial states (and the national liberation movements that were fighting for decolonisation elsewhere) held the promise that the part of the world then known as the Third World might supplant the Western proletariat as the global engine of revolutionary change. The weakening of left-wing institutions and growing prosperity at home made socialist revolution in the West an ever more remote prospect. In contrast, the Maoist vision of workers’ and peasants’ revolutions overthrowing colonial rule, thereby weakening the power of capitalism at home, offered a new focus for the dreams of Western radicals. America’s military troubles in Vietnam seemed to show what was possible. Some took this logic a step further and argued that the Western working class was not only incapable of revolution, but was even complicit in the colonial crimes of its own countries. Where the Old Left dreamed of class solidarity across nations, the New Left argued that colonialism created an insurmountable framework of conflict between occupiers and occupied. In this way of thinking, all of Europe was permanently cursed with the sin of colonialism, transferred since the Second World War to its imperialist offspring, the United States.