Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

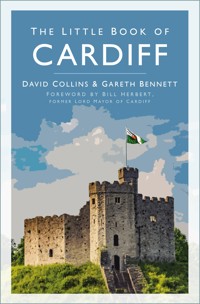

Did you know? - The city's coat of arms reads Deffro, mae'n ddydd – 'Awake, it is day' - Cardiff City Football Club played in chocolate-and-amber colours before they became the 'Bluebirds' - Brains Beer, said to be Wales' most famous drink, was first brewed in Cardiff during the 1800s Authors David and Gareth take a trip through the places, peculiarities and past practices of Cardiff, stopping off to sample the culinary (and alcoholic) delights of the city along the way. From Clark's Pies and a heaped helping of 'half and half' to the oddities of the 'Kaairdiff' accent, this fact-packed compendium reveals the contributions Cardiff has made to the history of the nation and recalls some of its famous faces – Shirley Bassey, Charlotte Church and Shakin' Stevens amongst them – and popular attractions. This book is sure to entertain, amuse and surprise everyone who picks it up.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 250

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS & BIBLIOGRAPHY

Much of the information on what Cardiff used to be like came, initially, from conversations with my father Keith Bennett. From the age of about 12, I had to hear all this stuff, and I suppose at some point during my 20s, I started actually listening to it! There were also recollections from my mother, Joan Withers, and stepfather, Frank Withers.

When I began reading newspaper pieces on ‘old Cardiff’, I found that Bill Barrett, Brian Lee and Dan O’Neill were a big help, although Dan, of course, does not deal in ‘nostalgia’ alone. I met Bill at the office of the Cardiff Post, and after I mentioned ‘nostalgia’, a reporter named Martin Donovan quickly intervened (jokily) with ‘Nostalgia?! You mean local history …’ Well yes, Martin, you were right, but at some point, one runs into the other – I note from reading David’s Splott piece that Bill was an influence on him, too, because he was his junior school teacher. Small world.

Once I started writing this with David, I raided my father’s book collection. I also had a book on Canton by Bryan Jones. This was very useful, not only on Canton itself (which ended up not being featured in this book, due to lack of space), but on the social changes which the country underwent during the twentieth century, and how they affected Cardiff.

Another useful source of information has been the Letters column of the South Wales Echo, where points of historical interest are sometimes raised. Personal experiences are a crucial source, although we have to bear in mind that often people disagree about what happened – so the more people who write in to verify such-and-such a point, the better. There is a chap who often writes to the Echo called Graham Williams. He gets ‘bees in his bonnet’ about place names, and half the stuff he writes I disagree with, but he is at least keeping discussions alive about places, place names and other things that might otherwise disappear entirely from our folk memory.

Bill Herbert’s colourful life story A Life Still Living formed part of David’s research on several chapters – an enjoyable read he assures me. David’s memories of Splott are also, as you will have seen, deeply personal.

His recollections of pop music, nights out and other escapades have informed many chapters, but he wishes to thank Grange Albion stalwart Tony Hicks for his input into the baseball piece and the staff of The Hollybush in Pentwyn for supplying the excellent pints of Brains he was able to enjoy in his research about beer! Let’s look at each chapter in a bit more depth though.

1: Cardiff – Where’s ’At, Then?

This chapter has multiple sources, including John Davies, A History of Wales (Penguin, 1994); The Chronology of Cardiff Castle by the Theosophical Society; and Tim Lambert, ‘A Short History of Cardiff’ in World History Encyclopedia.

2: Food and Drink

This chapter is almost entirely the recollections and experiences of David Collins – who doesn’t need reference books! However, he has spoken to others about some parts – including staff at Cadwaladers and his mate who actually works for Clark’s Pies. The Patrice Grill piece was simply what David could remember through the foggy haze of memory.

3: Civic Society

Information on the ‘Birth of a City’ section came from various sources. ‘Going Back to My Routes’ was written with reference to Bryan Jones’ Canton book, The Archive Photographs Series: Canton (Chalford, Stroud, 1995); Stephen Rowson & Ian Wright, The Glamorganshire & Aberdare Canals (Black Dwarf, 2001); D.S.M. Barrie, The Taff Vale Railway (Oakwood Press, 1982). Alan Price-Talbot’s recollections of travelling to London by train in the 1930s appeared in a letter to the South Wales Echo. The swastika story is recounted on the ‘Babylon Wales’ website. A tour of David’s attic also unearthed the wonderful volume Cardiff 1889–1974: The Story of the County Borough (Corporation of Cardiff, 1974). We also found some great leaflets about the City Hall up there and, finally, David looked up a few former colleagues at City Hall for their recollections of days gone by.

4: Sporting Cardiff

Cardiff City FC: David Collins, Born Under a Grange End Star (Sigma Leisure, Wilmslow, 2002 – one he did earlier!); Grahame Lloyd, C’mon City!: A Hundred Years of the Bluebirds (Seren, Bridgend, 1999); Richard Shepherd, The Definitive Cardiff City FC: A Statistical History (Tony Brown, Nottingham, 2002).

I have also derived much information, over the years, from the John Crooks books, self-published by the author in the late 1980s and early ’90s – a time when not too many people were interested in Cardiff City. I also interviewed Jim Wilson, son of CCFC founder Bartley, for O Bluebird of Happiness fanzine in 1990; still an important source of info about City’s early years.

Cardiff Rugby FC: David Parry-Jones (ed.), Taff’s Acre: A History and Celebration of Cardiff Arms Park (Collins, 1984); D.E. Davies, Cardiff RFC: History & Statistics 1876–1975 (Starling Press, Risca, 1975); Dai Smith and Gareth Williams, Fields of Praise: The Official History of the Welsh Rugby Union (University of Wales Press, 1980); David Parry-Jones, The Rugby Clubs of Wales (London: Hutchinson, 1989)

5: Around the Districts

Ely: Nigel Billingham and Stephen K. Jones, The Archive Photographs Series: Ely, Caerau and Michaelston-super-Ely (Stroud: Chalford, 1996); recollections by Keith Bennett.

Rhiwbina: Additional information from the late Malcolm Bennett (G.B.’s uncle), a long-time Rhiwbina resident. David also visited the Garden Village one sunny afternoon to gain a better feel of the place.

6: Going Out

We’re Going Down the Pub: David Matthews, The Complete Guide to Cardiff’s Pubs (Welsh Brewers, 1995); Brian Glover Cardiff Pubs and Breweries (Tempus, 2005); Brian Glover, Brains: 125 Years (Breedon, 2007).

Picture Palaces: Sources include Gary Wharton, Ribbon of Dreams: Remembering Cardiff Cinemas (Mercia Cinema Society, 1998); Mr Barker, various letters to the South Wales Echo; and recollections by Joan Withers and Keith Bennett.

Cardiff’s Nightspots: Information from Joan Withers and Keith Bennett; personal recollections of D.C. and G.B.; bits of info from other books, like Bryan Jones’ Canton book.

And the Band Played On: Recollections of Sarah Boubaker and a handy list of Capitol gigs from days gone by.

7: Where’s ’At Again?

David is grateful for information on the growth of Welsh in the city provided by the magazines of RhAG – Rhieni Dros Addysg Gymraeg. David also consulted the Cardiff Local Development Plan 2006–2026, which will set the planning framework for the city up until 2026, in researching this chapter.

Anyone who should have been mentioned but wasn’t – sorry, I forgot!

CONTENTS

Title

Acknowledgements & Bibliography

Foreword by Bill Herbert

Introduction

1 Cardiff – Where’s ’At, Then?

2 Food and Drink

3 Civic Society

4 Sporting Cardiff

5 Around the Districts

6 Going Out

7 Cardiff – Where’s ’At, Again?

Copyright

FOREWORD

I have seen so many changes in Cardiff, so many changes in South Wales.

I came to Cardiff after the Second World War. Before the war, I was a miner in Blackwood. I come from a world of pit ponies, pennant slab floors and chitlins for dinner. But the city of Cardiff offers a hearty welcome to outsiders – if they are willing to ‘make a go of it’ – as well as its own. And so, in time, this boy from Blackwood made it to Lord Mayor of the capital city of Wales.

Sometimes I shake my head at the memory and ask myself, ‘How did that happen?’ And sometimes I look at all the changes in the city over the years and I ask myself the same question.

This book has brought back so many memories for me. Of Tiger Bay, Shirley Bassey, Cardiff City FC – where, for my sins, I was a season-ticket holder for fourteen years – and, of course, the rugby. The whole city is spread out before you in these pages.

It has also got me thinking of other things, which are not included in these pages. Of political battles for the old Cardiff Central ward. Of so many names and faces that helped to shape the city. And of schemes which were proposed, but never came into being – like the Hook Road development, which would have cut Cardiff in half. They even wanted to knock down the Animal Wall once. I wasn’t having that!

In this book you can read about long-demolished steelworks, pubs that have been lost but not forgotten and the origins of our leafy suburbs. About life in Splott, Ely and Rhiwbina. About the finest civic centre in the country – and Caroline Street. It’s a colourful tale of the ever-changing tapestry of our city.

But this book is not all about the past. It’s about the present and even the future of the city. For, like time and the River Taff itself, our city flows ever on.

I was pleased to support this book. I hope you enjoy the many stories the boys unfold.

Here’s another one, which I was proud to share with them: Many towns and cities have a mayor. Some have a Lord Mayor. But only five have a Right Honourable Lord Mayor, and Cardiff is one of them! There are few other places like Cardiff.

Enjoy the book.

Foreword by William Penry Milwarden Herbert

Rt Hon. Lord Mayor of Cardiff, 1988–89

(But you can call me Bill!)

INTRODUCTION

This is a book about Cardiff. There have been books about Cardiff before, but we have written another one.

Why have we written it? Well, we wrote a couple of books about Cardiff City Football Club and our publishers, The History Press – who have printed a series of books about different cities, entitled The Little Book of … – asked us if we wanted to do The Little Book of Cardiff. So we said yes.

We have read some of the other books about Cardiff, and about parts of Cardiff. Many of them are built around photograph collections. Photos of ‘old Cardiff’ are a wonderful thing, which often show vividly (and more vividly than words) how Cardiff used to be. We have used some photos to help illustrate the book, but this is not primarily a photo collection.

We have tried to put everything we could think of that was interesting about Cardiff into this book. Ultimately, we had to leave a whole load of things out, because there was a limit to how much we could fit into the space. Hopefully it will be a bit different from other books that have been published about Cardiff. And maybe, if enough readers find it interesting, we might put the rest of the stuff into The Little Book of Cardiff, Volume II.

The year 2015 is a fairly momentous one for Cardiff. It marks 110 years since the place was granted city status (in 1905) and sixty years since it was officially designated as the capital city of Wales (in 1955). Perhaps equally importantly, the proliferation of ‘big-name’ stores in the city centre, and the run of major football finals that the Millennium Stadium has staged in recent years, have put the city very much ‘on the map’ as a leisure and tourist destination for people throughout the UK – and further afield. Cardiff is now, for instance, a frequent location for stag and hen weekends, which has added to the colour of the city’s nightlife.

A couple of other quick points: This book has been put together by two people and we have presented it in two different fonts, so that the readers can see who has written what. So Gareth’s stuff is written like this, and David’s is written like this.

This is a book about both the present and the past. I (Gareth) have been around for only a small bit (45 years) of this past, and David for a few years longer. But neither of us are ‘as old as Methuselah’. We have drawn our material not only from our own experiences, but also from printed sources and from the memories of people older than us.

Mistakes can sometimes arise, however, due to ignorance, misconceptions, misunderstandings, ‘urban mythology’ and even – heaven forbid! – false memories. I have been the principal editor of this work, so the final responsibility for such mistakes lies with me. If you do find any then I apologise in advance. But I hope there will only be a small number. Fingers crossed …

Gareth Bennett

2015

1

CARDIFF – WHERE’S ’AT, THEN?

An initial question: why is Cardiff there at all? I mean, why did they build a town in that exact spot? First of all, we will have to do a little bit of geography. But don’t worry, it won’t take long, and I’ll try not to make it too boring.

THE TWISTS OF THE TAFF

First things first, then: why is Cardiff there at all?

The answer to that question lies in a little stream that forms in some mountains up in mid-Wales, called the Brecon Beacons. This burbling backwater trickles for a bit, then joins another small brook. After dribbling on a bit further, twisting this way and that, it becomes a recognisable river. It has a name, too: the Taf Fawr or, in English, the Big Taff. A bit further on, a tributary joins it (the Taf Fechan, or Little Taff) and it becomes a bigger river. It gets less waggly and begins to flow in a distinctly southerly direction.

Our river wends its way through mountain passes and then drops down, forming a narrow valley. This is the Taff Valley. Eventually the people living in the whole region of Wales bore the nickname, lent by this river, of ‘Taffies’. (This tag of ‘Taffy’ sometimes amuses people from North Wales, who grew up living nowhere near the River Taff.)

There is nothing particularly special about the Taff. There are many other rivers like it, running south from these mighty mountains – the Beacons – into the Bristol Channel. These include the Usk, the Ogmore, the Afan, the Neath and the Tawe and their many tributaries. Together these rivers form a distinctive region known today as ‘the South Wales Valleys’.

Let’s forget about these other rivers now and concentrate on our river: the Taff. The River Taff, now in a narrow valley, carries on running south and is enlarged by the water running into it from its own various tributaries. The Cynon runs into it from the west, followed by the Rhondda. From the other side, a smaller river, the Taff Bargoed, joins it.

The Taff continues to work its way south, until the valley widens and almost vanishes, becoming instead a wide gorge (the Taff Gorge). Then the river enters a wide floodplain, flows for a few miles further, and empties into the sea at a large bay.

This bay was once called Tiger Bay, but is known today as Cardiff Bay. Around this bay, and in the floodplain, was built a town, and this town became known as Cardiff. In time, the town became a city. This book is about that city.

A Bit of History (Not Much, Mind)

We are going back a bit now, just for a little while, so bear with us. We are going back to the year 50 BC.

In those days, the whole of Britain was inhabited by people who spoke various Celtic dialects, all of them related to the language we now call ‘Welsh’. So you have to imagine a Britain where nobody spoke any English.

There was no single ruler of the island, as there were thirty-odd different Celtic tribes, each with their own chief. So, at this time, there was no England, Scotland or Wales, there was just one island, with about thirty different ‘countries’ or tribal territories contained within it.

THE SILURES – THE ORIGINAL CELTIC WARRIORS

In what we now know as Wales, there were three main Celtic tribes. In south-east Wales, the area that concerns us, were the Silures.

The Silures farmed the rich pastures of the Vale of Glamorgan. The Vale is a flat area just west of Cardiff, where calcium carbonate deposits in the soil have created fertile farmland. However, before the Celts came over from south-western Europe (possibly Spain) in about 500 BC, nobody knew how to farm this area.

The problem was that lowland soils were harder to plough than upland soils. The ancient people who were in Britain before the Celts used wooden ploughs, which were not strong enough to break up this soil, so the Celts introduced iron ploughs. Soon the soil was suitable for rearing cattle (who also pulled the ploughs) and growing crops. Thus began the agricultural tradition of the Vale of Glamorgan, which continues to this day.

The Silures also fashioned tools and weapons out of bronze and iron, and made clothes. They lived in huts with roofs of arched timber and walls made of wicker and thatch. Their religion involved worshipping sun gods and their priests were called Druids. They also had some chaps who wrote poetry, who were called bards. These were important too, because there was no written language yet, so the bards related the history of the tribe through poems and folk songs, which were passed from one generation to the next.

The Silures were mainly peaceful. But then again, you would not want to mess with them – they did not make their weapons for nothing. They built a large hill fort just west of the River Ely, called Caerau. From there, Silure watchmen could look down and spy the approach of any invading tribes.

The Silure kingdom extended from, roughly, the River Wye in the east, to the River Loughor in the west. Beyond the Loughor lay the land of the Demetae, a different Celtic tribe. The Brecon Beacons formed a northern frontier, a large physical barrier between the Silures and the Ordovices of North Wales. To the south lay the Bristol Channel, and across the channel lived the Dumnonii.

Although these tribes shared similar cultures and dialects, they did not regard one another as ‘fellow Celts’. That is a label that has been given to them by the professors of today, to distinguish them from other ethnic groups, such as the Anglo-Saxons, who came to Britain later. At the time in which they lived, the Silures and the other tribes were quite likely to fall out – over a border dispute, for instance, or persistent cattle-rustling – and start a war against one another.

When they fought, the Celtic tribes fought hard. They often raced into battle naked, covered from head to foot in blue paint called woad, screaming at the top of their voices like banshees. (Not Siouxsie and the Banshees, just banshees. If you don’t know what a banshee is, Google it!) When they killed rival tribesmen, they tended to cut their heads off and hang them on their belts. Nice.

However, the Celtic tribes were not always fighting one another. In times of peace, there was trading between them. Trade also went on with other Celtic tribes who lived in France and north-western Spain.

THE ROMAN INVASION OF SOUTH WALES

The Dumnonii had discovered tin down in Cornwall and began mining it. Some of the tin was shipped over to the Continent and sold or exchanged for luxury goods like wine and pottery. The Demetae in West Wales had similarly discovered gold in the Towy Valley, which they exported.

The British trade in tin and gold came to the attention of the Romans, who were busy building a huge empire spreading out from the Mediterranean. The Roman leaders decided that, if this island, Britain, had large deposits of tin, iron ore and gold, then it might be worth ‘having a look at’. The Romans didn’t bother much with trade treaties and such like; they had a large army, so they normally just ‘sent the boys in’. So, in AD 43, the Roman invasion of Britain began.

In South Wales, the Silures, led by the great warrior Caradoc, put up a fierce resistance. But the Romans had a clever idea. They thought that if they controlled the coast and the rich coastal plain of the Vale, the Silures would be forced up into the mountains, where it would be difficult for them to live. The Roman military leaders saw the River Taff flowing into the sea at the big bay and thought this would be an excellent place to build a proper castle.

So in AD 55, the Romans constructed this castle on the banks of the Taff. They built a bridge at the first place up the river where it was feasible to do so (Canton Bridge). Then they built their fort on the east side of the bridge. The castle still stands in the same place today.

This castle also gave Cardiff its name. The Silures saw the castle, gasped in wonderment at the solid construction, and named it Caerdaff, meaning ‘Fort on the Taff’. Over the years, the name mutated into Caerdyf and then Caerdydd. This name proved to be too tongue-twisting for the later settlers – the English – who changed it to Cardiff. To the Welsh speakers, it is still Caerdydd.

The Silures carried out guerrilla warfare from the mountains for a few years, but eventually had to give in and make peace on the Romans’ terms.

After that, everything changed. The Romans built a series of forts to control coastal Wales. The main one was at Caerleon, where their troops were garrisoned. Modern roads were then built linking these forts. One linked Caerleon with Cardiff and Neath: the original A48! Another one went from Ystradgynlais, across the heads of the Valleys, then down the Rumney Valley to Cardiff – the last section being the original North Road.

The Celtic leaders now spoke and wrote in the Roman language of Latin and adopted Roman culture. This persisted for 350 years, until around AD 400. Then, the Roman troops had to evacuate Britain to deal with threats to Rome from northern barbarians called Goths.

Nobody is now sure how many people remained in Cardiff after the Roman soldiers left. It may be that the fort was abandoned and that there was only a very small community of subsistence farmers left in the area.

ENGLAND AND WALES

One of the main things about Cardiff is that it is the capital of Wales. It is also the largest city or town in Wales.

But why is there a ‘Wales’ separate from ‘England’ at all? This is a question that puzzles many people in England – I know, because I used to live there.

Well, once the Romans left, there was a political vacuum in Britain. The Celts were now more united than before, with one leader, known as Vortigern, who came to power in about AD 425. But there was still a tendency for the Celts to revert to their old tribal differences – so nobody was very sure how united Britain would be if it came under attack once again.

A significant ethnic minority during this era was the English (or Angles). These were fair-haired people from Northern Europe – from the areas we now call Holland, north-western Germany and Denmark. They began to come to Britain during the Roman occupation, as soldiers working for the Romans. Many of them, after retiring, were allowed to settle in Britain, and English communities began to spring up on the east coast.

To the north of Britain, beyond the wall which the Roman emperor Hadrian had built, lived a fierce, warlike tribe of Celts who had never accepted Roman rule. These were the Picts. Vortigern was worried that, with the Romans gone, the Picts would launch sea-borne attacks on Britain’s east coast. To prevent this, he encouraged more English to settle on the coast, granting them land in return for defending the coast. This turned out to be a disastrous political policy instigated by Vortigern, as in around AD 440 the English mutinied against their Celtic rulers and tried to establish their own independent kingdom.

This began 250 years of warfare between the Celts and the English. It ended with the English living (in seven different kingdoms) in an area which eventually became known as England, while the Celts were pushed west into an area which became known as Wales.

A Note on Ethnic Terms

A quick note here on terminology: the Celts, whom we will now call the Welsh, did not call the English ‘English’. Their Celtic word for them was saes, meaning foreigner. From saes we also have similar words, such as saeson and saesneg. We also get variations like sassenach (a Pictish, and later Scottish word for the English) and saxon.

Mostly, though, these foreigners called themselves Angles, as many were from the area of Angeln, between Germany and Denmark. Their term of Angleland for their new land was eventually shortened to England; and so the Angles became the English.

The Angles’ name for foreigner, at this time, was wylisc. From this term we get the word Welsh – and also the Angles’ name for the land of these Welsh: Wales.

Of course, the Welsh didn’t call themselves ‘Welsh’ at this time. They called themselves and their land Combrogi or Cymru, and their language Cymraeg. (Other variations include Cambria and Cumbria, which remained Welsh for a long time.)

In AD 780, one of the Saxon kings, Offa of Mercia, started to build a huge earthworks (Offa’s Dyke) to signify the border between ‘England’ (which now consisted of three Saxon kingdoms of Northumbria, Mercia and Wessex) and ‘Wales’.

Hopefully that’s cleared up how ‘Wales’ and ‘England’ came into being. Now we need to get back to Cardiff …

THE NORMAN TAKEOVER OF SOUTH WALES

In 1066, the situation in England was transformed by another invasion. The Normans, a bunch of French-speaking Viking descendants, sailed over and beat the Saxons (aka the English). Led by William the Conqueror, they then took over the whole of England.

This need not have affected Wales, but the Normans were a greedy bunch, who ‘wanted the lot’. They quite fancied the nice farmland in the Vale of Glamorgan and, further west, in Pembrokeshire. William needed to reward the Norman lords who had sailed over with him, and whose men had fought for him. He did this by awarding them land.

As the Normans had not conquered the Welsh, Wales was at first left alone. But then William’s son, King William II, awarded his mate Robert Fitzhamon the title of ‘Baron of Gloucester’. Fitzhamon reckoned this title meant he ‘owned’ the whole of South Wales. He moved his forces west across the Wye in around 1090 and quickly took possession of the old Roman fort at Cardiff, which was then rebuilt in the Norman style. From this base he set about taking over South Wales, and by the end of the century the conquest was complete.

Fitzhamon ruled everything south of the Brecon Beacons, from Gloucester to Cardigan. He was one of the so-called Marcher Lords, who built castles along the Welsh border and coastline to keep the unruly Welsh hemmed in.

For a while, Wales retained some independence. But by 1536–42, when the so-called ‘Acts of Union’ were passed, the region had come totally within the jurisdiction of English law and government. John Bassett became the first MP to represent ‘Cardiff Boroughs’ in the English Parliament that year.

Of course, there was still a massive cultural difference between England and Wales: the most obvious being that the common people of Wales all spoke Welsh. But in constitutional terms, it could be argued that ‘Wales’ after 1542 was, more or less, part of ‘England’.

Yes, I know, we are getting off the subject again. When are we going to get back to Cardiff? Well, we are just getting there. Now, in a minute.

FROM THE NORMANS TO THE AGE OF THE ‘BLACK GOLD’

Okay, back to the story of Cardiff. We have covered a few invasions now, and it may be getting confusing. To sum them up: the Romans built Cardiff Castle and established the town; the Saxons pushed the Welsh out of England and into Wales, but didn’t get to Cardiff. The Normans did get to Cardiff, and took over the castle – and the town.

We have missed out the Vikings, who raided the South Wales coast in between the Saxon and Norman invasions, in around AD 850. They seem to have used Cardiff as a base during this period, and some Cardiff street names – such as Womanby Street and Dumballs Road – supposedly derive their names from Viking terms.

One imagines the Viking ships sailing up the Taff to just below Canton Bridge, which had become a dock. You have to picture Westgate Street as being the course of the river, which it was way back then, before the river was redirected to run west of it. So what is now Quay Street led from St Mary Street to an actual quay, where ships were loaded and unloaded. Further up from Canton Bridge, the river became quite twisty and unnavigable.

But the Vikings did not conquer South Wales or settle here. They came, they moored, they raped and pillaged, drank some pots of lager – and then they left.

Back to the Normans. After the Norman lords moved into Cardiff Castle, the township around the castle began to grow. Town walls were built, with gates at western and eastern ends (hence Westgate Street), and by 1126 a local Norman bigwig had become the town’s first mayor.

However, having an imposing stone castle in the centre of town did not guarantee that there would not be ‘disturbances’ from time to time. Welsh feudal chiefs did not like their loss of power to the Normans, and every so often there would be a rebellion. In 1158, Ifor Bach, the Welsh lord of Senghenydd, attacked the castle and carried off the local Norman ruler, William, Earl of Gloucester.

There were further attacks on the castle in 1294 and 1315. Then, in 1404, the last Welsh tribal uprising occurred when Owain Glyndwr