Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

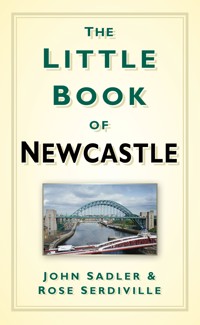

The Little Book of Newcastle is a funny, fast-paced, fact-packed compendium of the sort of frivolous, fantastic or simply strange information which no-one will want to be without. Here we find out about the most unusual crimes and punishments, eccentric inhabitants, famous sons and daughters and literally hundreds of wacky facts (plus some authentically bizarre bits of historic trivia). John Sadler's new book gathers together a myriad of data on Newcastle. There are lots of factual chapters but also plenty of frivolous details which will amuse and surprise. A reference book and a quirky guide, this can be dipped in to time and time again to reveal something new about the people, the heritage, the secrets and the enduring fascination of the city. A remarkably engaging little book, this is essential reading for visitors and locals alike.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 279

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE

LITTLE

BOOK

OF

NEWCASTLE

THE

LITTLE

BOOK

OF

NEWCASTLE

JOHN SADLER & ROSIE SERDIVILLE

First published 2011

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© John Sadler & Rosie Serdiville, 2011, 2013

The right of John Sadler & Rosie Serdiville to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUBISBN 978 0 7509 5400 6

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1.

Crime & Punishment

2.

History – Murder, Mayhem & Money

3.

Anatomy of a City – an Urban Landscape

4.

Citizens of Note & Notoriety

5.

Movement – the Transport Connection

6.

City of Commerce & Culture

7.

Ministers, Ranters & Witches

8.

Blood, Snot & Bile

9.

Howay the Lads! This Sporting Life

10.

Images of Tyneside

11.

On this Day in Newcastle

Bibliography

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors owe a debt of gratitude to the following: staff at Newcastle City Libraries, the Society of Antiquaries Library, North East Centre for Lifelong Learning, Tyne & Wear Archives, Robinson Library, Literary and Philosophical Society, Northumberland Archives, Gateshead Library, Adam Goldwater and Gillian Scott of Tyne and Wear Museums, Colm O’Brien of the North East Centre for Lifelong Learning, Dr Jo Bath for advice on witchcraft and witch-hunters, John Mabbit for his outstanding work on the City Walls of Newcastle, Richard Stevenson for his work on the Great Fire of 1854 and also to Chloe Rodham for the illustrations, another successful collaboration.

INTRODUCTION

Some four decades ago, the city of Newcastle formed a backdrop for the 1970s cult gangster movie Get Carter. So successful was Michael Caine’s performance as Kray-type henchman Jack Carter that a whole ‘Get Carter Heritage’ was inspired and begotten. Forty years on and the city looks very different, though the Get Carter connection of Gateshead’s toweringly squalid 1960s monstrosity of a municipal car park was of sufficient weight to grant numerous stays of execution.

The Little Book of Newcastle is not a full history or gazetteer, but a series of anecdotes drawn from the city’s rich history and cultural heritage. What we have tried to do is to give our readers an impression of the place, with all its many quirks and idiosyncracies.

Newcastle has a long and eventful history, from the days of the Romans to the Millennium Bridge, through centuries of bitter warfare, the heyday of coal mining and its status as powerhouse of the industrial revolution. It has its great Norman keep and long stretches of medieval walls, the famous Tyne bridges, a varied cultural, musical and theatrical heritage, ghosts, witches, body-snatchers and rock stars.

Then there’s football, of course.

John Sadler & Rosie Serdiville, 2011

Oh Newcastle by Irv Graham

Is there such a place as Eden

Lovely and serene

Oh yes there is my bonny lad

Valley of emerald green

Eden of my father

Newcastle upon the Tyne

Eden of my childhood

Wondrous and sublime

Could there be a spot of heaven

Abandoned by the Gods

Sitting here on earth

To survive against the odds

Look around my bonny lad

Each treasure will be thine

Such it is your heritage

Oh Newcastle upon the Tyne

1

CRIME & PUNISHMENT

RIOTOUS BEHAVIOUR

The year 1740 was a difficult one, more noticeably so for the poor. Harvests were meagre and unscrupulous grain merchants, identified as part of the urban elite and including Mayor Fenwick, were driving prices up by hoarding and profiteering. In barely half a year, prices shot up by a meteoric 160 per cent. By early June the swelling tide of discontent had expanded to riotous proportions. On the 9th of that month, keelmen and miners, acting in concert, helped themselves to the cargo of a grain vessel, a version of the Tyneside Wheat Party. Alderman Ridley was dispatched to negotiate and offered, more in panic than policy, a cap on prices; a bargain he was unable to support having no civic authority to barter on such terms.

As the situation continued to deteriorate and sensing indecision on the part of the wavering corporation, belligerent keelmen, on 26 June, marched towards the Guildhall, a raucous mob at their back. In rising terror, aldermen deployed a body of militia who, bayonets fixed and gleaming, barred the way at Sandhill. Someone fumbled or panicked, a musket flashed and banged, one youthful rioter tumbled lifeless. The protesters surged forward, overrunning the Saturday night soldiers and assailing the Guildhall as though storming the Bastille. The terrified merchants had barricaded themselves in as volleys of stones burst through glass like round-shot and the stout doors finally yielded. No more blood was spilt but the place was thoroughly sacked and the Corporation’s cashbox or ‘hutch’ became an early casualty. Wealth in the not inconsiderable sum of £1,200 was summarily redistributed.

Having failed to resist the mob, the chastened militia were ‘escorted’ back to their billets, many a felon released from custody and retailers encouraged to sell at the capped prices Ridley had offered. By dusk, however, their ire spent and dissipated through serious lubrication, the rioters dispersed. Next morning, yeomanry from the shires rode through deserted streets, rounding up the few who could be found. These, perhaps forty or so, were unlucky as summary trial and transportation awaited them.

LAW AND DISORDER

For several centuries a rich mercantile clique whose influence was based upon coal monopolies, known as ‘Hostmen’ (of whom rather more later) dominated civic life at all levels and extended their trade cabals to control the offices of local government. Affinity was the key to influence. Newcastle was a city much directed by an interlocking web of bonds. Circuit judges were entertained liberally by the Corporation as hosts. Relationships worked on several levels, both a web and layer cake. One example was Judge Jeffreys who, no stranger to the delights of cellar and table, was noted for ‘drinking to filthy excess till two or three o’clock in the morning, going to bed as drunk as a beast, and rising again with all the symptoms of one who has drunk a cup too much.’ To fortify himself for the arduous business of law, the judge continued to imbibe during sessions, allowing his particular brand of gallows humour ample free passage.

Newcastle was perhaps unique in the history of English urban settlement as, for centuries, it remained an outpost. Built as such by Romans, it was to stand in an embattled landscape until 1603, when the Union of the Crowns finally brought the border wars to an end. As a centre for the administration of justice, its gaols were to house some choice rogues, not all of whom accepted their captivity with passivity.

OF GAOLS AND GAOL-BREAKS

Newcastle was blessed with two major gaols for a large span of its history. Until the end of the fourteenth century, the town was under the jurisdiction of the County Sheriff. In the year 1400 Newcastle was awarded a grant of separate county status. Thereafter, the town maintained its own court within the Guildhall and lodged felons in Newgate Barbican. The castle itself and surrounding enceinte remained as part of the wider county process. This was both necessary and inevitable given that Newcastle was an island of urban settlement in a wild frontier landscape. The border wars effectively created a no-mans-land in the upland dales of Northumberland, largely depopulated and then resettled after the Scottish raids unleashed in the wake of Bannockburn in 1314. For over a decade the Scots enjoyed military hegemony, despoiling as far south as York, wasting the shire and levying blackmail from those settlements able to pay.

For just over four centuries the castle in Newcastle remained a gaol; filthy, dark and unsanitary, an echo of squalor and despair is still etched into the bare masonry of the guardroom where most prisoners were housed. One reformer, visiting during the late eighteenth century, criticised the vile conditions and deprecated the practice of showing prisoners like zoo exhibits to the public at 6d (2½p) a time. Categories of prisoners were not separated, nor indeed were the sexes with inevitable consequences. A number of the county and town’s citizens entered the world in the dread confines of the gaol.

CASTLE KEEP

At few points in its long history could the castle keep ever be defined as offering high security. One of the more notorious escapees was Sir Humphrey Lisle who got away in 1527. This knight had done good service against the Scots but meddled in Scottish border politics, thereby incurring the wrath of the Douglas Regent. Lisle and his son judged it wisest to withdraw to Newcastle to escape but the regent had a long reach and procured their arrest. Most likely both were held in the ancient prison adjoining the Black Gate, traces of which can still be viewed. Both Lisles escaped, with or without the collusion of their guards, joyfully ‘trashing’ their place of confinement in a burst of furious vandalism. Sir Humphrey went on to develop a new career as a reiver, allying himself with the Armstrongs and Liddesdale riders. He rode once too often, however, and, on his second visit to Newcastle, two years after his escape, fell once again into the hands of the authorities. He was immediately hanged without incarceration.

REBELLIOUS EARLS

When the Rebellion of the Northern Earls erupted in 1569, Newcastle was a frontier bastide in a situation which threatened to degenerate into civil war. The earls were soon corralled, however, by resolute local officers and one of their supporters, a notorious Armstrong rider, ‘Jock of the Side’, found himself in the keep awaiting execution. Little Jock had enjoyed a career that was both colourful and dramatic even by reiver standards and latterly became the subject of a celebrated border ballad. He could scarcely hope for clemency. Nonetheless, his Liddesdale cohorts had not forgotten him and they staged a daring raid on Newcastle. Like the later, even more famous escape of Kinmont Willie Armstrong from Carlisle, the operation proved a complete success. Jock was sprung and, well-mounted, he and his rescuers spurred northwards in a bid to reach the sanctuary of their own dark glen. Though a posse from the garrison, doubtless humiliated and outraged, spurred after, the Armstrongs made clean away, swimming the Tyne at Chollerford.

They scarce the other brae had won,

When twenty men they saw pursue;

Frae Newcastle toun they had been sent,

A’ English lads baith stout and true

Jock ’O The Syde

SHADOW OF THE GALLOWS

Maintenance of law and order was somewhat haphazard during the earlier period, no regular police forces existed and Newcastle was not infrequently a garrison town. Berwick, wrested from the Scots first in 1296 with a vast spillage of blood, would change hands no less than fourteen times until Richard of Gloucester, Shakespeare’s ‘Crookback Dick’, won it back for the final time (to date), nearly 200 years later.

It was not until 1763 that the Town Guard was formed, a rather ad hoc formation, many of whom were former soldiers distinguished by their dark greatcoats and bearing lanterns. Remunerated at the princely rate of half a guinea per week with a full guinea bonus, paid quarterly, their base was the porch of St Nicholas’ Church from whence, on the stroke of ten, they set off on nightly patrolling. Theirs was an unenviable task; dank, unsanitary wynds were a rookery of thieves and footpads, though each arrest was worth an extra shilling! Newcastle did not institute a regular police force until 1836; an attempt had been launched four years earlier but foundered in the face of vociferous protests from ratepayers, angered by the costs!

Things were certainly lively enough to justify it. In 1836 the chief constable noted the presence of 71 brothels and 46 houses of ill repute in the city. Action seems to have been inadequate; eighteen years later the number had grown to over 100. Presumably they drew a lot of trade from more than 500 pubs and beer shops. By the 1950s there were 44 of them on Scotswood Road alone.

Newcastle invented the high-speed chase. In 1900 a policeman commandeered a passing car to pursue a drunk on a horse. The car won but it was a close run – they only caught up with the horse a mile later.

The Elswick Riots in 1991 were widely reported nationally. They started when two young men burgling a house in Hugh Gardens were disturbed and climbed up onto a roof. People rampaged through the streets smashing cars, front windows and street furniture. It happened again a decade later: this time the main casualty was a local pub. Oddly enough, local crime writer Martin Waites set his novel White Riot in the same area.

OUTLAWS

We nearly had our own wild west. Butch Cassidy’s mam was born in Brandling Village. Ann Sinclair Gillies moved to America with her parents when she was a child (that’s my mam’s maiden name!).

The police box at the top of the Bigg Market was the first in England.

A HANGING MATTER

For many years Newcastle’s Town Moor was one of the most popular venues for any decent hanging. Invariably these outwardly sombre occasions were guaranteed crowd-pullers. In 1532 thirty members of the Armstrong affinity, notorious reivers all, were turned off en masse, albeit at the equally popular Westgate gallows. Their severed heads provided a gruesome garnish to the castle’s walls. The litany of crimes which merited death was a long one and the Corporation retained the services of an appointed hangman. This was no sinecure, the appointee would be called upon to earn his stipend:

21 August 1752, Richard Brown (keelman) hanged for the murder of his daughter

19 August 1754, Dorothy Catinby hanged for the murder of her illegitimate children

7 August 1758, Alice Williamson (sixty-eight) hanged for burglary

21 August 1776, Andrew McKenzie (soldier) hanged for highway robbery

21 August 1776, Robert Knowles (postman), hanged for opening letters and stealing from them

JANE (‘JIN’) JAMESON

Hangings combined due solemnity with free festive cheer. As Jane Jameson was led to her execution in 1829, the cavalcade comprised the town sergeants on horseback with coked hats and swords; the town marshal also on horseback in his official costume; the cart with the prisoner sitting on her coffin, guarded on each side by eight free porters with javelins, and ten constables with their staves; then came the mourning coach containing the chaplain, the under sheriff, the gaoler and the clerk of St Andrews. Jane, or ‘Jin’ as she was commonly known, ‘a disgusting and abandoned female of most masculine appearance, generally in a state of half nudity,’ sold whatever she could scrounge and, despite her unprepossessing looks, her favours by the Sandgate fountain.

Nor was her temperament calculated to endear. She was addicted to drink, foul-mouthed and fouler-tempered. Both her illegitimate offspring died young. Her mother, an altogether more respectable pensioner, lived in no. 5 the Keelman’s Hospital, the nearest thing to sheltered accommodation that nineteenth-century Newcastle had to offer. For some time Jane resided with her mother, also giving house to her current partner, Billy Ellison.

The pair celebrated New Year 1829 in their favoured, gin-soaked manner and, having exhausted their own slender purses, attempted to persuade Jane’s mother to fund the ongoing binge. A fearful and protracted row ensued, culminating in Mrs Johnson accusing her daughter of the murder of both her children. Jane, in a paroxysm of drunken rage, seized a poker and drove it spear-like through the old woman. Despite the dreadful wound, Mrs Jameson did not die immediately but survived for several days. Even then, she attempted to divert blame from Jane, alleging she’d fallen onto the poker by accident. Nobody believed her, including the jury at Jin’s trial for murder. The verdict was never really in doubt and Jane went to the gallows on 7 March.

GOING OFF IN STYLE

Much imbibing accompanied these popular civic occasions and the accused was expected to play his or her part by treating the crowd to a suitably rousing or witty oration. Highwaymen particularly, as befitted their cavalier trade, could usually be relied upon to go off with aplomb. One Henry Jennings, whose neck was stretched for rustling in August 1786, ‘gave an explanation of the cant terms used by robbers and pickpockets etc which he desired to be published for the benefit of the public’.

O’Neil the highwayman, hanged in 1816, was another who met his obligations to an attentive public:

The cart stopped, and on being drawn under the gallows, O’Neill addressed a few words to his two brothers. He gave one a handkerchief and a watch. He then embraced and took affectionate leave of them. He shook hands with the gaolers and executioner. The cap was drawn over his head and after a few private ejaculations he was suspended. The executioner fulfilled his office well. O’Neil’s struggles were short and there was but one evolution of nature.

Once the barber-surgeon pronounced life in the condemned man to be extinct, the corpse was taken by friends and family to be ‘waked’ at a nearby hostelry before a more solemn interment in St Andrews.

Mark Sherwood was the last man to swing on the Town Moor when, in 1844, he was condemned for murdering his wife.

BAD BEHAVIOUR

For the citizens of Newcastle the town had yet more unseemly pleasures to offer besides public executions. Today’s ne’er-do-wells who stagger down the length of the Bigg Market are unwittingly maintaining a long tradition of unruliness and bad behaviour. Only the lighting has markedly improved. As far back as 1745 the Newcastle Courant was complaining of ‘outrages and disorders lately committed in the Bigg Market’ – in this instance some twenty-eight offenders were arrested, four of whom were flogged, one sent to don a red coat and another quartet gaoled. Many a Journal reader would no doubt thoroughly approve. As a port and, to all intents and purposes, garrison town, Newcastle offered a range of services. For example, the Quayside was long the haunt of loose women. Writing in the 1820s Aeneas Mckenzie, with suitably Calvinistic disdain, warned his readers of the moral dangers of consorting with those Cyprian Nymphs who flaunted their charms so openly on the bustling waterfront and in the maze of narrow chares behind.

Sir Walter Scott offers a pen portrait of the Catholic or ‘Recusant’ gentry of eighteenth-century Northumberland in Rob Roy – the Osbaldistones of Osbaldistone Hall, hard-drinking, hard-riding, swift of temper and as swift to draw steel. In 1752 in the smoky confines of Pinkney’s rather notorious Bigg Market Ale House a soldier from General Guise’s regiment, Ewan MacDonald, took exception to the anti-Scottish nature of a fellow drinker’s ribaldries and, in the brawl, ran him through. This was a busy year for matters of honour – ship surgeon Henry Douglas choked out his life-blood on the Quayside at the conclusion of a sanguinary duello with Edward Holliday.

THE MAN WHO SIMPLY WOULDN’T DIE

Even as he mounted the scaffold, however, MacDonald’s story was to take a rather sensational twist. At this final moment, the ex-soldier panicked as the noose was placed and, kicking at the hangman, threw him clear from the gallows. Doubtless such inconveniences were something of an occupational hazard and, undeterred, the executioner returned to his task and this time MacDonald was left kicking air. The body, in the usual way, was taken to the Surgeons’ Hall for anatomical dissection (see below). Only a single student was in the building and, to his mounting horror, he witnessed the dead man come back to life! This time the hangman, perhaps diverted by his fall, had bungled the job. MacDonald, reviving, began to plead for his life. He was wasting his time as the student calmly bludgeoned him to death – a case of third time unlucky. When the student bludgeoner, who had boasted of his swift remedial action, was soon after kicked to death by a skittish horse, some whispered the dead man’s spirit had entered the animal!

AN AFFAIR OF HONOUR

One of the most notorious encounters between gentlemen of the better sort took place by the old White Cross on Newgate Street. The ‘feid’ (feud) or vendetta was a long-established Northumbrian and border custom. John Fenwick of Rock and Ferdinando Forster of Bamburgh were both men of substance, the latter being an MP. Both were guests at a grand jury luncheon held in the Black Horse Inn on Newgate Street. A drink-fuelled altercation followed, each seemingly encouraged by the raucous company. Next morning, when heads should have cleared and blood should have cooled, a chance encounter sparked a resumption of verbal abuse followed by swords. Both men were skilled at arms and for a while the blades bickered and parried without hurt. Forster suddenly lost his balance, slipped and stumbled; his enraged opponent delivered a killing stroke. The White Cross and Black Horse Inn are long gone, though Forster’s impressive tomb survives in the chancel of Bamburgh church.

A SURFEIT OF LEAD

In the early hours of a midsummer’s morning in 1764, the respectable Mrs Stewart, wife to a pawnbroker, found her slumbers disrupted by the drunken chorusing of Robert Lindsay, keelman and noted reveller who was serenading all Sandgate from their yard wall. The lady ordered the drunkard to be off but he became abusive, her resolute assault with a handy pair of hearth tongs easily rebuffed. Now Mr Stewart was awakened and threatened the garrulous intruder with an unloaded blunderbuss. The couple’s first joint attempt at a warning shot proved little more than a flash in the pan, a failure which reduced Lindsay to paroxysms of laughter. His last, however, for a second shot, blasted in anger, killed him instantly. On 27 August 1764, Stewart paid for ill temper with his life, his name added to the long list of those who danced to the hangman’s tune on Town Moor.

THE MYSTERIOUS CASE OF THE SAVINGS BANK MURDER

The work of John Dobson as architect and Richard Grainger as developer changed the face of Newcastle and created the magnificent sweep of Grey Street, acknowledged as one of the finest in Britain. Now destroyed and a bare facsimile hidden away beneath the ghastly pile of Swan House, sits the rump of the Royal Arcade, completed in 1832. Superbly located, as was hoped, adjacent to the likely site of a new main station, this development was quickly snapped up. One of the key lettings was to the prestigious Savings Bank. This initial burst of affluence was short-lived and, with the station now constructed elsewhere, the Royal Arcade went into swift and irreversible decline.

None of this was apparent a mere six years after the grand opening. On 7 December 1838 firemen responded to the alarm when smoke was seen pouring from the building. When they entered nothing could have prepared them for what they saw. Joseph Millie, an employee, reposed in the sack-like indifference of death, his blood and brains garnishing the room. The murder weapon, a bent and spattered poker, lay nearby. The dead man’s pockets had been stuffed with paper in an attempt, quite plainly, to remove all traces by fire. The victim was not alone for beside him was the semi-conscious form of Archibald Bolam, a senior figure in the bank.

Bolam’s story was a bizarre one. He claimed he had been the recipient of a series of menacing letters, the last of which had arrived at the bank that very day. He averred that this made him fearful for the wellbeing of his housekeeper and he had returned home to warn her. It was thus after hours when he re-entered the bank. He found Millie already dead and was himself suddenly and savagely assaulted by a largely unseen assailant who had then fled, leaving him for dead. His story simply did not hold up, the firemen did not believe he was actually unconscious when they entered; nor did the physical evidence tally. Over the next few weeks following his arrest on suspicion of murder, investigation revealed Bolam was far from being as respectable as he claimed. His housekeeper was also doubling as live-in mistress and he was a gambler and frequenter of bawdy houses.

While his account of events on the fatal day clearly did not add up, there was little or no motive for a murderous assault upon Joseph Millie. The two were habitually on good terms; there was no sign of embezzlement on Bolam’s part. In his summing-up at the trial, the judge directed that at worst he was guilty of manslaughter brought on by some inexplicable fit of murderous madness. Suitably impressed, the jurors returned a manslaughter verdict and Bolam cheated the rope. Rather, he was transported to Australia where the Botanical Gardens in Sydney still features an ornamental sundial gifted by Bolam who had served his time and then prospered. The truth of the case will never be known.

GETTING EVEN WITH THE REVENUE MAN

One of the many entrepreneurs who created what would now be termed ‘small and medium-sized enterprises’ in the heady Victorian era of expansion was Mark Frater, a former tax-collector who had invested in building up an omnibus company. One of the rising city men, just past fifty years of age he kept an office at no. 2 Blackett Street. On 1 October 1861, a fine autumn morning, the omnibus proprietor paused at the entrance to his office building to chat with a friend. In an instant, this mundane scene was transformed into one of horror.

George Clark who resided, appropriately, close to St Nicholas’ churchyard was a failed artisan who had allowed a petty dispute over an unpaid dog licence to escalate. In those days, Frater, as collector, had levied distraint upon Clark’s tools. Brooding upon his loss Clark became obsessed with his intended victim. Already of a morose and violent disposition, this obsession soon turned to a murderous rage. On that fateful day, he struck, driving a 5in blade deep into his unsuspecting victim’s neck. The mortally wounded Frater was carried into his office where he quickly succumbed to shock and blood loss. Clark was to spend the rest of his days in an asylum for the criminally insane.

MURDER ON THE ALNMOUTH TRAIN

On 18 March 1910, John Innes Nisbet, bookkeeper at Stobswood Colliery near Widdrington, aged forty-four, was found shot dead on the morning train at Alnmouth station. Outside of Agatha Christie novels, railway murders are relatively rare.

The victim, a resident of Heaton, had boarded at Newcastle. His attaché case contained a substantial sum in wages (£370 9s 6d), which he’d been due to pay out. Clearly, then, robbery was not a motive. Police established that the killing must have been committed between Stannington and Morpeth stations, although no murder weapon was found.

The crime became something of an overnight local sensation and the victim’s funeral was well-attended. A reward was posted and, three days later, a bookmaker’s clerk, Alexander Dickman, was arrested and charged. Evidence against the accused was scanty despite widespread and lurid speculation concerning a supposed relationship between alleged killer and victim. Dickman’s subsequent trial and its ‘guilty’ verdict seemed, to many observers, as resembling something of a travesty. Nonetheless and despite a nationwide appeal for clemency, no appeal was allowed and the convicted man was hanged, still protesting his innocence.

RESURRECTIONISTS

Condemned murderers and criminals whose necks had been stretched upon the gallows were still destined for a measure of civic duty once departed. That is, in terms at least of their mortal remains, for there was a thriving trade in dead flesh. Even notorious cases like Jane Jameson, aged thirty at the date of her execution, provided meat for the dissection table. The Surgeons’ Hall, a fine classical edifice, stood aloof from the surrounding squalor of Pandon and Manors, where the carcasses of dead felons such as Jane were displayed for some hours in the courtyard as a ghoulish diversion. After the public had tired of this spectacle the corpse was boiled and flayed to create an anatomical exhibit which eminent practitioners such as John Fife could use as a tool for lecturing. Once the cadaver had been probed and dissected, the remains were simply cremated. Now, of course, we have PowerPoint.

This constant need for anatomical specimens had engendered the pernicious trade of ‘resurrectionists’. Nobody on Tyneside quite matched the notoriety which Burke and Hare achieved in Edinburgh, although the pair had spent some time as immigrant labourers in Sunderland where, perhaps, they began their ghastly trade. The Anatomy Act of 1832 was intended to relieve pressure upon medical schools needing a constant supply of recent corpses for teaching and experimentation purposes. The statute provided that any cadaver, remaining unclaimed for 48 hours post mortem, could be properly handed to a medical school.

Prior to this, a decent cadaver might fetch 10 guineas; no mean sum. John Fife was much taken with a local pie-seller, John Cutler, who was physically handicapped. The vendor’s anatomical deformity led Fife to offer 10 guineas for dissection rights upon his death. Cutler was not at all offended and readily accepted the offer. The Newcastle Courant recorded a funeral in 1826 when the deceased, clearly not greatly mourned, was being carried to his funeral and the mourners, losing interest, found the lure of an ale house more compelling. With only the undertaker and pall bearers remaining in the diminished cortège, the group simply shifted tack to the Surgeons’ Hall where the deceased, a miser in life, together with coffin was simply traded on to the dissectors!

A CORPSE TOO SOON

John Fife was not just an eminent medical practitioner but a local politician of radical leanings with links to Chartism, anathema to his more conservatively minded contemporaries. He served twice as mayor and made a virulent enemy of his successor and rival John Carr. On 7 December a certain Mrs Rox died in All Saints’ Workhouse. Her relatives, being unlettered, were unaware of the provisions of the Anatomy Act referred to above and assumed, naïvely, that the cost of interment would be borne, as previously, by the parish. Not so of course. No sooner had the time period elapsed than the deceased was whisked off to Surgeons’ Hall. The family were outraged. Being devout Catholics, their fury spread like wildfire through the hovels and tenements of Pandon. Mayor John Carr was not normally one to espouse popular unrest – indeed, this was what he detested most in Fife – but his hated rival was, of course, a leading surgeon.

It was Carr, the high Tory, who led a ranting, steaming mob to the gates of Surgeons’ Hall (now the Medical School). Carr demanded entry and proceeded to threats when nervous inmates demurred. Thoroughly intimidated, the students unbarred their portal and the mob streamed it. Just in time, the late Mrs Rox was due for ‘processing’ and her mortal remains snatched from the dissecting table in the very nick of time to be transported in semi-regal state to a lusty wake and finally burial in All Saints’. It is clear nobody had troubled over the fate of this unfortunate woman while she still lived. The magistrates subsequently fined the Medical School, deciding the porters had been a mite overzealous in removing Mrs Rox’s body ahead of the statutory deadline; for John Carr, his consorting with the mob provided a neat little win over his radical opponent, Fife.

The iron railings around All Saints’ churchyard were not intended purely for decoration. These, and many like them, were erected to deter body-snatchers – resurrectionists. Surgeons were apt to ask few questions if any and 10 guineas proved a significant incentive. Frequently it was more outlying cemeteries which were targeted. In response, metal frames or ‘mort-safes’ were positioned over fresh burials until sufficient time to allow decomposition to spoil market opportunity had elapsed. So pernicious was the curse of the body-snatchers that some communities erected watch towers and stationed guards over their graveyards.

LEFT LUGGAGE AT THE TURF HOTEL

Prior to the construction of Lloyds’ fine new banking hall on Collingwood Street, this was the site of the Turf Hotel, a noted coaching inn, where the York to Edinburgh coaches halted. The booking office provided temporary storage for all manner of goods in transit, some of which might abide there for a period if a connection was missed. Coaches did not run on Sundays out of deference to the Sabbath. In September 1825, the clerks were alerted to a rather nauseous odour apparently emanating from a sealed trunk. This was destined for a James Syme, whose address was given as no. 6 Forth Street, Edinburgh. The watch was summoned and a magistrate present when the chest was rather gingerly opened up. Inside was the body of a teenage girl, almost certainly one who had died of natural causes and whose body had been stolen to feed this rapacious medical market. She was never named and subsequently laid in a paupers’ grave.