Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

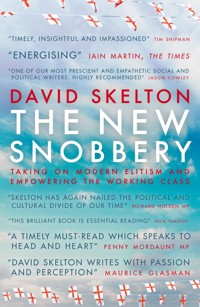

"Timely, insightful and impassioned." – Tim Shipman "David Skelton is, once again, excellent … This brilliant book is essential reading." – Nick Timothy "One of our most prescient and empathetic social and political writers. Highly recommended." – Jason Cowley "Skelton gets it … A timely must-read which speaks to head and heart." – Penny Mordaunt MP "Vital … Skelton makes a compelling case." – Jon Cruddas MP *** An insidious snobbery has taken root in parts of progressive Britain. Working-class voters have flexed their political muscles and helped to change the direction of the country, but in doing so they have been met with disdain and even abuse from elites in politics, culture and business. At election time, we hear a lot about 'levelling up the Red Wall'. But what can actually be done to meet the very real concerns of the 'left behind' in the UK's post-industrial towns? In these once vibrant hubs of progress, working-class voters now face the prospect of being minimised, marginalised and abandoned. In this new updated edition of his rousing polemic, David Skelton explores the roots and reality of this new snobbery, calling for an end to the divisive culture war and the creation of a new politics of the common good, empowering workers, remaking the economy and placing communities centre stage. Above all, he argues that we now have a once-in-a-century opportunity to bring about permanent change.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 305

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

“David Skelton was talking about levelling up and the potential for a Conservative breakthrough with the abandoned working class long before either was a glint in Boris Johnson’s eye. In this timely, insightful and impassioned book, he explains how a new snobbery is alienating the progressive left from the working people of Britain. If you want to know why the Red Wall is turning Tory, and how the post-Brexit political realignment might become permanent, read this book. I suspect Boris Johnson will have half a dozen copies on his bedside table before too long.”

Tim Shipman, political editor,Sunday Times

“David Skelton is, once again, excellent. For those baffled by the new snobbery – the disdain directed towards working-class people for daring to think for themselves or for wanting a better future for their families and local communities – this brilliant book is essential reading.”

Nick Timothy, former Downing Street chief of staff,Daily Telegraph columnist and author ofRemaking One Nation: The Future of Conservatism

“If you want to understand why Labour’s Red Wall crumbled and why the Conservatives are not only winning but changing, read this thoughtful book by one of our most prescient and empathetic social and political writers. Highly recommended.”

Jason Cowley, editor-in-chief,New Statesman

“Skelton gets it. Levelling up is about practical change, but it is also about how we value others, release potential and restore respect and appreciation for one another. A timely must-read which speaks to head and heart.”

Penny Mordaunt MP ii

“Insightful and informative, The New Snobbery is a must-read for anyone aiming to understand the politics of the 2020s.”

Nadhim Zahawi MP

“For many years David Skelton has been a political pioneer in his attempts to develop a distinct ‘blue-collar’ conservatism. In recent times, with talk of ‘levelling up’, his party has moved decisively in his direction. In this vital book Skelton urges them to complete the journey by embracing a new pro-worker settlement: one built around dignified and fulfilling work, which renews our vocations, empowers and rewards workers and strengthens their voices and communities. He makes a compelling case, not just in terms of political calculation but in the name of justice. I don’t know if the Tories will listen to and embrace Skelton’s ideas, but if they do, my party should really start to worry.”

Jon Cruddas, Labour MP and author ofThe Dignity of Labour

“David Skelton writes with passion and perception about the fear and loathing that progressives feel for the working class.”

Maurice Glasman, Labour life peer and director of the Common Good Foundation

“Skelton has again nailed the political and cultural divide of our time: the prejudiced, narrow and increasingly hysterical elite versus the mass of decent, moderate people who just want to see themselves, their families and their long-ignored communities stand tall again. If the Conservatives want to hold on to not only the ‘Blue Wall’ but also No. 10, they should listen to Skelton.”

Richard Holden MP

“The New Snobbery is an energising book that will be read and digested by ministers and policymakers.”

Iain Martin,The Times

iii

v

‘Some ideas are so stupid that only the uneducated can believe them.’

The Observer, November 2019

‘It’s time for the elites to rise up against the ignorant masses.’

Foreign Policy, June 2016 vi

CONTENTS

PREFACE

WHY HAVE I WRITTEN THIS BOOK?

Why did I decide to write this book? And why now?

The first reason is very personal. I might not live in Consett any more, but my friends and family do, and I have spent the past few years listening to them being routinely insulted by people who regard themselves as ‘progressive’ and ‘enlightened’. Wrapping up the writing of this book was difficult, because every day brought a new example of (generally, but not always) left-wing people finding new ways to describe the working-class as bigoted or stupid. I saw prejudice against people I care about and places I love become acceptable in so-called ‘polite society’, in progressive Britain and in parts of the media. The people I know and love who voted for Brexit and (after much soul-searching) voted Tory for the first time in 2019 aren’t stupid, bigoted or racist – in every way they’re exactly the opposite. The real prejudice is coming from the elitists who use political disagreement as an xexcuse to throw around snobbish abuse. I’m not prepared to stand back and let my friends and family be insulted in this way; I think it’s important that this snobbery is called out for what it is – hence my decision to write this book.

The second reason is political. The years since the Brexit referendum have seen the Tory Party move in the direction I’ve long been advocating: towards a genuinely One Nation politics that embraces an active state in order to bring about economic renewal to places that badly need it. I don’t need to be persuaded of the importance of ‘levelling up’. I saw my hometown devastated by the loss of the steelworks that gave it pride and identity, and then be forgotten about by generations of politicians who had simply moved on. I’ve seen proud work replaced with insecure jobs that provide neither meaning nor dignity. I want this book to be a reminder that working people should not be forgotten any more and that the call they made for change in the referendum of 2016 and the election of 2019 must be responded to with the kind of decisive economic reform that dramatically improves people’s quality of life.

Now is a once-in-a-century opportunity to achieve a permanent realignment in British politics, based on a multi-racial, working-class Conservatism, with Conservatism always acting in the interest of workers. Just as my last book, Little Platoons, saw the real potential for towns in England’s north and the Midlands to set the path xitowards a Tory majority, this book seeks to suggest the kind of lasting change that would make the realignment of December 2019 into a permanent one. The May 2021 elections, with the Conservatives taking the Hartlepool by-election with a dramatic swing and Labour losing councils as symbolically important as Durham, showed that December 2019 was not a one-off. Now is the time to be bold and deliver the kind of change that voters in Hartlepool and County Durham voted for.

The third reason is about timing. Now that Brexit is done, we have the autonomy and the tools to remake our economy. The grimness of the Covid crisis has shown how significant so-called ‘elementary’ workers are to the economy and has also illustrated the importance of having a strong manufacturing sector. Post-Brexit and post-Covid presents the opportunity for a remaking of the economy along the lines I set out in this book, where dignity of work is central, working people are respected and represented throughout society and a revived manufacturing base restores pride to towns across the country, as well as creating millions of skilled jobs.

The fourth reason is about what I have learned over the past few years since I wrote Little Platoons. I have had the good fortune to be able to see in person what the ‘Asian Tigers’ – Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan – were able to do with intelligent industrial policies to create a strong manufacturing base, just as other countries xiiwere giving up on industry. This has reaffirmed my view that British policy-makers have had much too narrow horizons for too long. Rather than endlessly trying to relitigate the British political arguments of the 1970s and 1980s, or having pointless arguments about street signs, it is surely about time we looked to those countries who have developed strong manufacturing bases, skilled work and strong communities and see what we can learn from them.

INTRODUCTION

THE BIRTH OF THE NEW SNOBBERY

The 2016 referendum on EU membership marked the first time in generations that the once industrial working class flexed its political muscles and helped to change the direction of the country – against the almost universal advice of the ruling political, business and cultural class. Three years later, the same voters proved pivotal to the result of the 2019 general election, with the so-called Red Wall crumbling and 120 years of class-based partisan loyalties melting away as dyed-in-the-wool Labour voters abandoned the party, handing the Conservatives their biggest majority since Margaret Thatcher’s heyday. After decades of being ignored and left behind, working-class voters seemed to be central to politics again. And this resurgence came not a moment too soon; working-class voters have continued to face the prospect of being economically marginalised, minimised in cultural life and abandoned educationally. 2

Sadly, for too many this new-found working-class voice is a source of regret rather than celebration. A new and insidious snobbery, aimed squarely at these voters, has taken root in part of elite society. For too many people, these election results didn’t just mark a political disagreement, they also represented an unacceptable displacement of the natural order of things.

All of a sudden the ‘wrong people’, apparently uninformed and driven by bigotry, had proven decisive in electoral events. As a particularly angry editorial in Foreign Policy magazine put it, the divide was seen as ‘between the sane and the mindlessly angry’.1 To disagree with the status quo was to display a level of ignorance that shouldn’t just be disagreed with but blatantly disregarded as ‘insane’ or based on mindless stupidity. This effortless superiority, writing off much of the country as barely worthy of being taken seriously, has become the calling card for much of contemporary progressive Britain.

Large parts of the often liberal, professional elite seem to believe that working-class views are not of the same worth as professional views; working-class jobs are not as valuable as middle-class jobs; and working-class places are less desirable to live in than middle-class places. This has created a new snobbery, through which it has become socially acceptable for the economically successful to look down on working people.

What actually constitutes working class is obviously a 3discussion that has raged for centuries. For the purposes of this book, we’ll largely define working class based on education (not in receipt of a degree) and occupation, although it is also worth noting that the majority of people still define themselves as working class, despite decades of commentary suggesting the opposite. The British Social Attitudes Survey indicates that 60 per cent of people regard themselves as working class, and notes that ‘the proportion who consider themselves working class has not changed since 1983’.2 Only around 35 per cent of the country had a degree when that was measured in 2012, but because of the expansion of higher education this figure could well be higher now.

TWO TIERS

For too much of elite Britain, a tone of disdain against the traditional working class represents the only socially acceptable form of prejudice. This is particularly, but not exclusively, on the liberal left, where the disdain is based sometimes on pity, sometimes on rage.

Words like ignorant and racist are thrown around freely and unfairly. Despite polling evidence that levels of racism in the UK are declining and are lower than in most of Europe, critics are keen to stereotype Brexit Britain as a dystopia of bigotry. The response to political changes driven by working-class voters isn’t to accept that such 4alterations were based on considered choices and legitimate grievances but instead to insist that views that the managerial elite personally disagree with must be based on poor education, parochialism or a lack of sufficient enlightenment. For many politicians of the left, which is now a largely middle-class, city-based movement, the working-class vote now represents a reactionary obstacle to their progressive worldview.

Some Labour politicians in working-class areas have long regarded many of their constituents as some kind of embarrassing elderly relative, to be humoured come election time but otherwise largely ignored. As part of an explosive post-election argument, the former MP for Doncaster claimed that a Labour frontbencher and Islington MP told an MP from a Leave-voting constituency that she was ‘glad my constituents aren’t as stupid as yours’. Although Emily Thornberry has strongly denied making the comment, the fact that such stories are believable says much about the resurgence of snobbery. As former Home Secretary Alan Johnson reminded a leading Corbynista on election night: ‘The working classes have always been a disappointment’ for the left.3 Another Labour MP, Dawn Butler, said, ‘If anyone doesn’t hate Brexit … then there is something wrong with you.’4 The political decisions that have been galvanised by working-class towns have led commentators and politicians to lament a crisis of democracy, otherwise defined as democracy producing the wrong results. 5

Comedians, who are first to loudly claim to be offended in most circumstances, are the first to savage so-called ‘crap towns’ within the UK and ridicule narrow-minded, proletarian values. The likes of the BBC’s The Mash Report and Radio 4’s The News Quiz had a regular habit of punching down. Now popular theories allege that white working-class voters are the arch representatives of the newly popular concept of ‘white privilege’ or ‘white fragility’. Working-class men are either caricatured as football hooligans or ‘gammons’. Working-class patriotism is condemned and belittled, with book titles such as 52 Times Britain Was a Bellend causing a stir amongst the anti-patriotic new snobs. Parts of the professional middle class have shown themselves unwilling or unable to treat many working-class views, attitudes and cultures with anything other than contempt. A left-wing radio DJ commented on a poll giving the Conservatives a lead in the Hartlepool by-election with the musing that the town’s voters backing Tories was down to ‘forelock-tugging stupidity’, adding that the voters were ‘thick as pigshit or pig ignorant’.5

Once the scale of the Hartlepool defeat for Labour had become clear, elements of the left indulged in another round of electorate blaming. One claimed that the problem for the left was that ‘a huge number of the general public are racists and bigots’ and asked, ‘How do you begin to tackle entrenched idiocy like that?’ Another claimed, ‘We don’t have an opposition problem. We have 6an electorate problem.’ Hartlepool was yet more proof that the electorate don’t take particularly kindly to being sneered at and being told repeatedly that they are wrong, stupid or both. Results like the Hartlepool by-election and Labour losing control of Durham Council, the first it had gained as a party in 2019, was further evidence that a realignment, accelerated by left-wing snobbery towards working people, was continuing apace.6

THE PERMANENT CITADELSOF THE NEW SNOBBERY

Whilst working-class voters have been making their voices heard at the ballot box for the first time in decades, the new snobbery has strengthened its hold over other important institutions in British life, including the judiciary, upper echelons of the media and government agencies. Despite an obsession with diversity, decision-making bodies in culture, business and broadcasting have little or no real representation of working-class life nor provincial towns. This results in decisions that often seem made in defiance of the majority of UK citizens. Activist judges and power-sucking quangos have gradually increased their power over the years. These bodies have become permanent institutions of minoritarian dominance, the embodiment of the managerial elite, very much separate from the democratic sphere and using their power to 7entrench norms and values anathema to many working-class voters.

Universities, despite conscious efforts to broaden their social bases, have remained resolutely middle class (only 13 per cent of white working-class boys on free school meals attend). Indeed, attending university has almost become an inherited right amongst the professional middle class, building up borders and boundaries between them and the so-called uneducated majority. Vocational education is routinely mentioned as ‘a good idea’ by politicians and commentators, but for the professional middle class it is only a good idea for other people’s children.

Underpinning this new snobbery has been an all-embracing cult of meritocracy: the belief that success is always and everywhere down to hard work and talent, whilst lack of success is based on individual failure. Hence the snobbery of the successful towards the views of the less successful is seen as being justified by merit and talent. This has coincided with a two-tier economy created by the decline of skilled manufacturing and the growth of graduate jobs. Deindustrialisation created a social and economic blight that impacted several generations and is still being felt today. ‘Wealth creators’ have become lionised; professional careers have been defined as the only reasonable option; and superstar CEOs have grown used to seeing their views venerated in a cult-like way. At the other end of the social scale, many jobs have been robbed 8of dignity and respect and workers have found their voices ignored.

TILTED POLITICS AND ECONOMICS

For over three decades, politics, economics and culture became tilted in favour of the metropolitan middle class and the south-east and London. Politicians were predominantly from this professional background, and economic policies were predominantly designed to benefit these voters. This approach to economics saw a focus on delivering ‘value’ for shareholders and executives rather than investing in and respecting workers. Prosperity, success and growth tended to be pooled amongst the successful. Others saw decades of stagnation. The only possible goal for those ‘left behind’ was to aspire to join the professional middle class themselves. This tilting saw working-class voters robbed of economic power, political representation and cultural engagement.

The tidal wave of snobbery that accompanied the attempt to restore some economic dignity and political control was based on the overriding belief amongst much of the professional middle class that they had the right to have the game tilted in their favour. The snobbery didn’t emerge with Brexit or the collapse of the Red Wall, but those events made such views seem acceptable and pushed them to the forefront of political discourse. And 9this denigration of the traditional working class came at a time when they needed political and economic backing more than ever. As mentioned above, these communities have been hit by decades of stagnation since the loss of industry, damaged by languishing real wages since 2008 and were amongst the hardest hit by the economic impacts of Covid. Political inequality has seen working-class voices marginalised, with some 85 per cent of MPs being graduates; economic inequality has seen hard work go unrewarded, with almost two decades of stagnating wages; educational inequality sees less intelligent rich children overtake poorer children by the age of six. White working-class boys – hardly a fashionable group to champion – have become the most educationally disadvantaged group in the country.

NEW SNOBS AND OLD SNOBS?

For a while, snobbery seemed to be restricted to a few cranks and eccentrics. The old school tie still mattered, and a handful of people still became agitated over whether ‘loo’ or ‘toilet’ was the right word to use. But the old concept that there was a link between social background and human worth seemed old fashioned half a century ago. People would have been incredibly reluctant to express this snobbery in public and would almost certainly have been castigated for it if they had. 10

The new snobbery is different from the old and is, in many ways, more harmful. It is much more likely than the old to doubt the ability of the poorer and less well educated to play a proper and informed role in a democracy. Indeed, in many ways modern snobbery has more in common with the anti-democratic oligarchs of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries than the often ridiculed snobs of the post-war period. The old snobbery often went unspoken, whereas the new often dominates cultural output. A shared national experience, including the sacrifice of world wars, helped to erode class boundaries and bolster national solidarity, whereas the new snobbery is built from diminished national solidarity and limited shared experience. Today’s snobbery seems worryingly acceptable and bites at the heart of modern Britain. A successful professional elite feels that they owe their position to talent rather than birth and feels comfortable making public their disregard for the views, habits and culture of the working class.

More and more, the elite not only live separately from the rest of society, with mixed communities a thing of the past, but have next to no social interaction whatsoever. Aside from a social and economic gap, too often the impression is given that a great swathe of metropolitan, professional Britain doesn’t much like their fellow citizens and feels at best resentful of any economic and political influence they might have. The common patriotism that 11used to unite people is now often not felt by the metropolitan class. Social bonds and sympathies are limited, and institutions that once bound the classes together are no longer in existence. A snobbery at the top has often been responded to with resentment from those being looked down upon, as threads of solidarity have frayed. This gulf in understanding is not inevitable. It could be replaced with a pro-worker politics of the common good that aims to recapture a feeling of social solidarity and provides greater power and representation to working people.

TOWARDS A PRO-WORKER POLITICS

Our goal must be a politics that delivers power, accountability and opportunity to people long deprived of all three, helping to restore a sense of societal solidarity and the common good. This will mean moving beyond rhetoric and pushing forward an agenda that involves a genuine and lasting shift of power to working people. If the Conservative Party wants to make the temporary realignment of Labour voters in 2019 into a permanent one, only an agenda that genuinely enhances the strength, pride and esteem of working people will suffice. This will mean ending the disproportionate power of capital over labour; restoring the dignity of work and the strength of vocation and manufacturing; and giving working people a voice in the as yet impenetrable cultural bastions. 12

241Notes

1 ‘It’s time for the elites to rise up against the ignorant masses’, Foreign Policy, 28 June 2016.

2 British Social Attitudes Survey 33, 2016.

3 Benjamin Butterworth, ‘Jeremy Corbyn “couldn’t lead the working class out of a paper bag”, Alan Johnson says after exit poll result’, i, 13 December 2019.

4 ‘Dawn Butler: “If anyone doesn’t hate Brexit – even if you voted for it – there’s something wrong with you”’, Turning Point UK, 13 December 2019.

5 Terry Christian, tweet, 10.16 a.m., 4 May 2021, https://twitter.com/terrychristian/status/1389509343222157312

6 Dan O’Hagan, tweet, 7.07 a.m., 7 May 2021, https://twitter.com/danohagan/status/1390548709537157121; Alex Green, tweet, 9.12 a.m., 7 May 2021, https://twitter.com/GlexAreen/status/1390580177378463745

CHAPTER ONE

THE POLITICAL MARGINALISATION OF THE WORKING CLASS

‘These fat old racists won’t stop blaming the EU when their sh*t hits the fan … Absolute sh*tbag racist w*nkers.’

Labour MP, September 20201

‘An ex-miner sitting in the pub calling migrants cockroaches … is not the [sort of] person we are interested in.’

Paul Mason, 20192

‘The proletariat has discredited itself terribly.’

Engels to Marx in the 1860sas working-class voters supported ‘reactionary’ parties following the extension of suffrage.3

Early on EU referendum night in June 2016, the emphatic Leave vote in Sunderland made the political establishment aware that things were not going entirely 14to plan for the Remain campaign. Equally emphatic votes then followed in town after town, and it was clear that the working-class vote was driving a shuddering rebuke to the political, cultural and business elite. The entire establishment had lined up behind the Remain campaign as part of what David Cameron ensured voters was a ‘once-in-a-lifetime decision’. The final poster of the Remain effort couldn’t have been more emphatic: ‘Leave’, it promised, ‘and there’s no going back.’

Despite these fine words, once the Sunderland vote became clear, social media brimmed with righteous indignation and angry words. ‘Ignorant idiots,’ from places described as ‘sh*tholes’ and worse by angry Remain supporters, were condemned for ‘stealing our future’. As dozens more towns like Sunderland, including my hometown of Consett, delivered equally resounding verdicts, the class hatred from parts of middle-class Twitter became more and more virulent. A viral petition the day after the vote, calling for the result to be overturned because of the folly of the masses, gained momentum, with another eventually gaining over 4 million signatures.

Snobbery was back. But the modern snob had dispensed with the monocle and waistcoat and was instead armed with a social media account, a mountain of self-righteousness and, in many cases, an angry opinion column. The belief that Brexit was the result of something between mass hysteria and mass stupidity allowed 15a lingering sense of suspicion about less-educated people to boil over into open snobbery. This new snobbery was more damaging than the old because it was deemed to be socially acceptable. The elite who had dominated the politics and economics of the previous decades were quick to denounce the ill-informed mob, with the same virulence that many of their predecessors in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries had used to warn of the ‘dangers of democracy’.

As the dust settled in the days and weeks after the referendum, many of the modern elitists made clear their view that this was an unacceptable overturning of the natural order of things. The British meritocracy had, they argued, ensured that the most talented were doing well in the new knowledge economy and the least talented, without the ambition or the get up and go to succeed, had been ‘left behind’ by their own lack of education and intelligence. The new snobs screamed repeatedly that these ignorant fellow citizens should not be able to crush their European dream.

Leave voters were quickly derided as low-information, low-intelligence people and were accused of being sold what John Major mocked as a ‘fantasy’. The elite response was both hostile to the working class and, in some ways, virulently anti-northern. This backlash was marked by anger at the working class for ignoring the warnings of their perceived betters. We were repeatedly told that 16they were ‘turkeys voting for Christmas’ without the sufficient nous to understand that they were apparently voting against their own economic interests. At times, the snobbish backlash descended into outright nastiness, such as when Remainers said they hoped the Nissan plant in Sunderland would close because Sunderland’s ‘stupid Leave voters would deserve it’. Others said they would be ‘pleased’ if the fishing industry was harmed by Brexit as ‘they [my emphasis] got what they voted for’.

Few took a step back and considered why a political and business elite responsible for the Iraq War, the banking crash, and the biggest growth in insecurity and squeeze in living standards for almost two centuries should be meekly thanked by a grateful electorate for their superior wisdom. Instead, great swathes of the elite turned their anger on the voters who had dared to point out that the status quo wasn’t working for them. They didn’t consider that voters in the north, who had seen the economy go from industrially dominant to one of the least productive in Europe, might have had a point when they refused to celebrate south-eastern prosperity and the loss of investment and infrastructure in their areas. The fact that, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies, the UK is one of the most geographically unequal economies in the OECD wasn’t regarded as a justifiable reason to protest through the ballot box, following a referendum campaign that had celebrated what was described as decades of prosperity. 17It wasn’t considered logical that voters in the north-east, long ignored or taken for granted, had a legitimate grievance that their GDP per person had shrunk to less than half of that in London. The new snobs instead returned to pre-democratic language that questioned the ability of the mass of voters to make up their own minds.

The post-industrial working class might have been pivotal in two of our most recent major electoral events, but many of their political opponents could not hide their contempt in their reactions. A bulk of these residual Remainers had done very well out of the economic modernisation that had left so many behind. Many professional circles in big cities simply assumed that their educated colleagues had voted Remain, and many couldn’t hide their disdain for those from other parts of the country and in less successful parts of the economy. Few even stopped to acknowledge that this phase of political polarisation was partially driven by an economic polarisation that decision-makers had long ignored.

OPEN SEASON FOR SNOBBERY

Open snobbery towards working-class voters has been on display since the 2016 referendum – a blatant lack of belief in the ability of lesser educated voters to make valid political decisions, combined with ugly, often contemptuous, language. This snobbery is accompanied by more 18systemic disengagement of the working classes. Despite the increased political importance of these voters, they remain badly unrepresented across politics and shut out from a variety of institutions.

The Labour Party, the traditional vehicle for working-class interests, is now, in the words of its own internal report, the party of ‘high-status city dwellers’.4 The political left has come to represent a credentialed and wealthy elite with what Christopher Lasch described as ‘a satisfying sense of personal righteousness’, who often see working people as reactionary barriers to progress.5 The Conservatives have started to transform their voting coalition and now command greater working-class support than Labour. They have done so by backing away from market fundamentalism, but a large portion of the right-wing element of the political class remains in thrall to the economic liberalism that caused many of the issues we face today.

The political class continues to be dominated by high-status, professional graduates with the views and values generally representative of that group. Some combination of freedom of movement, freedom of capital, unfettered free trade and various elements of economic and social liberalism are common currency amongst them. Often vapid TED Talks are venerated, and counterculture imagery is used to obscure the fact that priority is 19given to policies that benefit the professional class, such as open borders and the abolition of tuition fees, rather than policies that would benefit the wider population, such as building dignity at work or tackling the housing crisis.

Praiseworthy social progress, such as the legalisation of gay marriage, can’t obscure the fact that the politics of the pre-referendum period had been almost predominantly run in the interests of the professional middle class, and that working people have continued to fall further behind. Although politicians have courted the working class with appeals to ‘strivers’ or ‘alarm-clock Britain’, governments of all parties have consistently promoted finance over manufacturing and graduates over non-graduates. In ten years, spending on higher education increased by 43 per cent, whilst spending on further education fell by up to 23 per cent.

Not only has politics has become less representative of working-class voters, with almost 90 per cent of MPs now being graduates, there is also a growing values gap between mainstream voters and the political class. As we will come to in more detail later in this chapter, the views of voters in general, tilting to the left economically and to the right culturally, remain badly underrepresented. That class remains highly devoted to social or economic liberalism (or both). Those members of the political class 20who understand the need to tackle economic insecurity are often devoted to a cultural liberalism, and those who understand cultural insecurity are often devoted to policies that accelerate economic insecurity.

The only possible route for British politics is one that backs away from snobbish attitudes and focuses on ensuring everybody, whether they have a university degree or not, is able to make a good, secure, dignified living, and one that allows working-class voices to again be represented at the heart of British life.

ALL OPINIONS ARE EQUAL, BUT SOME OPINIONS ARE MORE EQUAL THAN OTHERS

To paraphrase Orwell, too many people in modern Britain believe that ‘all opinions are equal, but some opinions are more equal than others’. The traditional working class now see their views sneered at and frowned upon from across the political spectrum, but particularly on the modern left. Elites, long used to having their worldview accepted unquestioningly, have reacted to the renewed importance of working-class voters with barely hidden disdain. Political difference, apparently, isn’t down to logical thought or first-hand experience but due to ignorance, racism and stupidity.

This has led to a democracy in which large parts of 21the elite hold the views of the public in different levels of esteem, with the views of the traditional working class having less validity than the opinions of the professional middle class. Elements of the elite, happy to accept the misplaced view that economic success is down to talent rather than good fortune, have extended this concept to the belief that the professional middle class are the modern equivalent of philosopher kings – better able to make public policy decisions than their less educated and less economically fortunate countrymen.

Professional disdain for working-class views has created a grotesque inequality of political worth. This is multiplied by the existence of what some academics have described as educationalism or credentialism, with intolerance based on levels of educational achievement seen as the only acceptable type of prejudice. This is particularly injurious in the UK, where working-class young people are consistently let down by the education system. This then leads to a situation where the traditional working class are not only let down educationally but also marginalised economically and either ignored or mocked politically. One poll in the US even found that almost a fifth of American liberals would be upset if an immediate family member married somebody who hadn’t been to university. It would be a surprise if such a result wasn’t replicated in the UK. 22

A cross-university study in 2016 concluded that

in contrast with popular views of the higher educated as tolerant and morally enlightened, we find that higher educated participants show education-based intergroup bias: they hold more negative attitudes towards less educated people than towards highly educated people … Less educated people are seen as more responsible and blameworthy for their situation … meritocracy beliefs are related to higher ratings of responsibility and blameworthiness, indicating that the processes we study are related to ideological beliefs.6

In other words, lack of education, which is increasingly correlated to class, is now used by the better educated to justify prejudice against poorer citizens. The research also showed that many wealthier, better educated citizens were unapologetic about feeling this disdain and happy to blame the less successful for their own misfortune.

French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu went as far as condemning a bigotry of intellect. This allowed the creation of what he called a ‘theodicy of the elite’, which justified the social order and rationalised existing privileges. Such a pattern can clearly be seen in the way the political views of less educated citizens are all but written off by many parts of the professional elite. A healthy democracy 23cannot be one that sees a large part of the elite regarding the majority with contempt.

BIGOTS? HOW POLITICAL SNOBBERYBURST OUT INTO THE OPEN

Post-referendum research showed that professional (AB) voters were the only social group to have a considerable Remain sentiment, backing continued EU membership by around 18 per cent. For finance workers in the City of London, the gap was over 40 per cent.7