Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: epubli

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

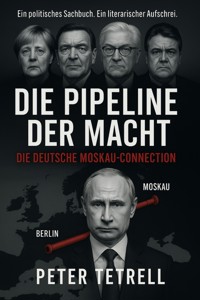

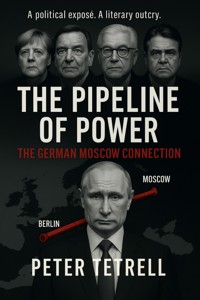

What this book is – and what it is not This book is not an indictment. It is a record. A dissecting look back at decisions, speeches, treaties, protocols, reactions. Everything is documented. Everything can be read. Nor is it a polemic. Where the facts speak, pathos is silent. But it is not a neutral report either. For neutrality, where human dignity is at stake, is not a virtue – it is a betrayal of the Enlightenment. The architecture of deception Germany's policy toward Russia over the past 25 years can be described as a pipeline—not just made of steel, but of decisions: •2001: Putin's speech to the Bundestag – the beginning of an illusion •2004: Schröder calls him a "flawless democrat" •2007: Putin threatens in Munich – Germany remains silent •2008: War in Georgia – and Nord Stream is built anyway •2014: Annexation of Crimea – and Nord Stream 2 is approved •2022: War of aggression against Ukraine – and some remain silent Every stage is documented, every decision can be analyzed. Who bears responsibility? It does not lie with any one individual. It belongs to a system that turned cowardice into loyalty and economic opportunism into moral argument. A system that was supported by democratically elected actors – with open eyes but closed files. The question for all of us Why was this policy able to persist for so long? Why did the media, parliament, and the public look away for so long? Was it just economic calculation? Or is there a deeper failure behind it – a failure of political judgment, of historical sensitivity, of responsibility toward future generations?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 352

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Table of contents

1. The deception: how it all began

How Schröder, as chancellor, sought closeness to Putin. The beginning of the friendship – and the promise of cheap gas.

2. Years of rapprochement

Frank-Walter Steinmeier's role as the foreign policy architect of the opening to the East, his closeness to Lavrov, and the ideological foundation.

3. Putin's vision of power

Merkel's ambivalent role: a cold face, a warm pipeline. Nord Stream 2 as geopolitical capitulation – and her silence after the war.

4. Anatomy of a project

How two pipes through the Baltic Sea became a symbol of Europe's dependence. Contracts, constructions, billions. Chancellor Schröder as Putin's extended arm.

5. A turning point in the Bundestag

Schröder's decline from representative of the people to Gazprom man. Who went with him – and who left him behind.

6. A continent under pressure

Former ministers, state secretaries, business leaders. A cartographic analysis of the network.

7. The sabotage

"An explosion in the depths – and on the surface, a decade of German-Russian energy policy is shattered."

8. Germany, Europe's faltering hegemon

How Kiev has been warning since 2006 – and how Berlin listened but said nothing.

9. The media and the fairy tale of change through trade

How narratives were established. Who wrote them. And who never questioned them. Putin cheerfully continues to murder.

10. The SPD – a party in Moscow's shadow?

Connections, party foundations, city partnerships. Why the SPD was particularly deeply entangled.

A chronology of looking away. The last attempt to acknowledge responsibility – before the archives close.

Foreword: The silence of the years

Later, people will say they didn't know.

People will make excuses, saying they only did what everyone else did. That they had good reasons – economic, diplomatic, party political. They will refer to files, to conversations, to the lack of alternatives. And they will hope that no one asks what they really knew – and when.

This book is a response to the silence. A chronicle of omissions. An examination of the naivety, the turning of a blind eye, and the deliberate complicity – over 25 years of German policy toward Russia.

It's not just about Putin. It's about us.

It is about a political class that traded cheap energy for moral integrity. About ministers, chancellors, lobbyists who knew who they were getting involved with – and did it anyway. About networks that turned business relationships into habits, friendship into dependence, interests into servitude.

It's about the SPD – but also about the CDU. About leftists who used the Kremlin narrative. About right-wingers who stylized Putin as a bulwark against the West. And about a Germany that didn't want to listen when journalists, dissidents, secret services, and Ukrainian presidents had long been sounding the alarm.

This is not a neutral book. It makes a claim: to truth, to naming, to transparency. It does not mince words, and it does not hide behind well-formulated retrospectives.

For the history of German policy toward Russia is not a history of diplomacy. It is a history of repression, stupidity, fear—and self-interest.

Anyone who asks today how things could have come to this should start with themselves. And with those who were elected to protect the German people – and instead broke their oaths in exchange for warm offices, stable election results, and career guarantees.

This is not a book for the archives. It is a book for investigative committees.

And for all those who wonder how much a country can forget before it loses itself.

Prologue

The man with the flowers

"It is the silent part of history that screams the loudest."

Berlin, a cloudy November morning in 2022.

A man steps out of an armored limousine. Dressed in black, wearing a coat down to his ankles, he holds a bouquet of flowers in his hand—white roses, freshly cut, no ribbon. He walks slowly across the damp cobblestones, past rows of graves of Russian prisoners of war, past memorial stones engraved with dates that meant war for other generations – 1917, 1941, 1945.

The man has grown old. His gait is stooped, his face gray, but he carries the pride of a man who has never explained himself. No press entourage accompanies him, no microphones, no official recorders. Only a single bodyguard remains at a distance.

He stops.

In front of the grave of Alexei Nikolayevich – who fell at Stalingrad. Next to it is a memorial plaque for a certain W. Putin, donated by a Russian veterans' organization. The camera of a passerby captures the moment, but she does not recognize him. The scene is lost in the digital noise of the day.

The man is Gerhard Schröder.Former chancellor.Gazprom lobbyist.The lost son of social democracy.And symbol of a political era whose legacy continues to this day.

A quarter of a century of deception

The story told in this book is not a simple tale about natural gas, pipelines, and East-West dialogue. It is the story of a mistake—a historical mistake that was not made out of ignorance, but out of arrogance, vanity, and cowardice.

A mistake that shaped Germany for over 25 years.A mistake that began with applause in the Bundestag – and ended with sirens in Kiev.

A mistake that was not made by dictators alone, but by democrats who should have known better.

This is not just about Schröder.

It's about Frank-Walter Steinmeier, who helped shape the SPD's Ostpolitik for years and was never held accountable.

It's about Angela Merkel, who provided political cover for Nord Stream 2 and is now writing a book about "freedom" as if she had nothing to do with this story.

It's about Manuela Schwesig, Sigmar Gabriel, law firms, lobbyists, business leaders.

It's about banks, supervisory boards, foundations.

And it is about a country that could see – but did not want to see.

Gas in exchange for silence

Over two decades, Germany built a political energy architecture based not on reason but on wishful thinking:– That change through trade would work.– That it was possible to negotiate with autocrats on an equal footing.– That Russia was brutal internally but useful externally.

These assumptions permeated ministries, party conferences, and economic summits.They determined arms decisions, sanctions – or the lack thereof.And in the end, they cost not only political credibility, but also human lives.

What this book is – and what it is not

This book is not an indictment.It is a record. A dissecting look back at decisions, speeches, treaties, protocols, reactions. Everything is documented. Everything can be read.

Nor is it a polemic.

Where the facts speak, pathos is silent.

But it is not a neutral report either. For neutrality, where human dignity is at stake, is not a virtue – it is a betrayal of the Enlightenment.

The architecture of deception

Germany's policy toward Russia over the past 25 years can be described as a pipeline—not just made of steel, but of decisions:

2001

: Putin's speech to the Bundestag – the beginning of an illusion

2004

: Schröder calls him a "flawless democrat"

2007

: Putin threatens in Munich – Germany remains silent

2008

: War in Georgia – and Nord Stream is built anyway

2014

: Annexation of Crimea – and Nord Stream 2 is approved

2022

: War of aggression against Ukraine – and some remain silent

Every stage is documented, every decision can be analyzed.

Who bears responsibility?

It does not lie with any one individual.It belongs to a system that turned cowardice into loyalty and economic opportunism into moral argument.A system that was supported by democratically elected actors – with open eyes but closed files.

The question for all of us

Why was this policy able to persist for so long?Why did the media, parliament, and the public look away for so long?

Was it just economic calculation?Or is there a deeper failure behind it – a failure of political judgment, of historical sensitivity, of responsibility toward future generations?

A final look

The man with the flowers has long since left the place.All that remains is a grave.And a story that was never told to the end.

This book begins where official memory politics ends.It reconstructs what was said, decided, and omitted.Not out of revenge—but because memory also demands justice.

Chapter 1: The Pipeline of Power

The deception – How it all began

"Those who want to divide Europe offer peace and deliver gas."

Berlin, September 25, 2001 – Plenary Hall of the German Bundestag

Bundestag President Wolfgang Thierse (SPD) welcomes the Russian president:

"Mr. President! Mr. Chancellor! ... This honor ... confirms the interest of Russia and Germany in mutual dialogue."

Seated in the front row were:

Chancellor Gerhard Schröder (SPD)

Vice President Anke Fuchs (SPD)

CDU parliamentary group leader Friedrich Merz

CSU Deputy Leader Rudolf Seiters

Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer (Greens)

FDP Vice President Hermann-Otto Solms

PDS Vice President Petra Bläss

This group represented the Presidium of the 14th Bundestag – in other words, Germany's political leadership at the time.

Putin's speech – German, charming, inconsequential

Two weeks after September 11, Putin appeared as a speaker in the Bundestag for the first time. He began his speech in Russian, then continued in almost flawless German. He evoked a "Greater Europe" stretching from Lisbon to Vladivostok, emphasizing shared culture, democracy, and cooperation against terrorism. There was repeated applause – and even a standing ovation at the end.

But his rhetoric contains warnings: he criticizes NATO's eastward expansion as a potential danger, laments an incomplete Europe, and points to the need for a separate security architecture without US dominance (German Bundestag).

First doubts – who leaves, who stays

Green Party MP Werner Schulz then demonstratively leaves the chamber, which is interpreted in Germany today as an early sign of mistrust ( FAZ.NET ). But the majority remain seated – impressed, uncritical, euphoric.

The context around 2001

Putin's domestic policy developments

were already evident: censorship, consolidation of power, arrest of oligarch

Mikhail Khodorkovsky

(2003). The West hardly resisted.

On the other side stands Germany's policy:

After the Chechnya War (2004), Schröder called Putin a "flawless democrat."

Steinmeier (Foreign Minister) focuses on dialogue – even after the 2007 Munich Security Conference.

Merkel is still new in office, but remains diplomatically reserved.

The first crack in the façade

In his speech, Putin makes it clear that Europe must redefine itself – without constraints and stereotypes. The audience applauds, but at the same time Germany misses a historic moment of clarity.

A published Bundestag transcript and numerous media reports (FAZ: "Putin in the Bundestag: How he wrapped everyone around his finger in 2001") attest to a mixture of fascination and dangerous naivety in the chamber ( FAZ.NET ).

First conclusion: the silence of power

Germany applauds, Putin's speech ends as a symbol of fatal misjudgment. The political elite—Schröder, Merz, Fischer, Steinmeier, Solms, Seiters—leave the historic signal uncommented: The pipeline of power does not begin with concrete pipes, but with words that were misunderstood.

Summary – what happened

Event

Date

Importance

Putin's speech in the Bundestag

Sept. 25, 2001

First German stage for Putin; supportive atmosphere despite warnings

Presence of German politicians

SPD, CDU/CSU, Greens, FDP, PDS; government and opposition leaders

Symbol of political unity without critical distance

Werner Schulz leaves the hall

immediately after speech

Individual protest vs. majority applause

First signs of authoritarian development

2001

No political reaction to consolidation of power in Russia

Putin's appearance and the German applause mark an early turning point: Germany deliberately underestimated the strategic dimension of this man. The political will to maintain a critical distance was lacking – despite all the warning signs. This failure would later have costly consequences.

Chapter 2: The pipeline of power

Section 2.1. 2001–2007: Years of rapprochement – How Germany made Putin's system socially acceptable

Sept–Dec 2001: Euphoria after the speech – and the first ties

The speech in the Bundestag on September 25, 2001, reverberated in Berlin – not only in the arts pages, but also in ministries, party foundations, and boardrooms.

Joschka Fischer, then foreign minister, told the Tagesspiegel newspaper in October 2001:

"We have a historic opportunity to build a new security architecture with Russia."([Source: Tagesspiegel archive, Oct. 2001])

Wolfgang Clement (then Minister of Economics, SPD) meets with a Russian delegation from the Ministry of Energy in November – topic: "Long-term energy supply for Europe" – a euphemism for Gazprom connection.

The first strategic papers on the "energy partnership with Russia" are being drafted in the Federal Chancellery under the leadership of Frank-Walter Steinmeier. Internal memos from the Foreign Office, which came to light in 2016 through investigative research by Correctiv, show that as early as the end of 2001, there were considerations to turn to Russian gas in the long term – with political backing.

Chapter 2 – Section 2.2

2002: Schröder, Putin – and Gazprom's invisible hand

"Personal closeness is a poor guide in foreign policy. Unless it replaces the compass."

March 2002 – Schröder to Moscow

In the spring of 2002, German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder traveled to Moscow for a two-day working visit. On the official agenda: talks on energy, counterterrorism, and “building economic bridges.” What sounds harmless is in fact a meeting of strategic importance – in retrospect, even the beginning of a deep economic interdependence with Russia, the consequences of which would only become apparent years later.

Vladimir Putin did not receive Schröder in Sochi or at an EU summit, but in a small circle in the Kremlin. The images that later appeared on ARD's Abendschau news program showed two men who not only understood each other but also appeared to be almost friendly: shoulder pats, laughter, an almost intimate tone of voice that one otherwise only hears in one's own living room.

That same evening, the German Press Agency (dpa) sends out a quote from Schröder that causes a furor—not in Germany, but in Poland and the Baltic states:

"We can trust Russia because we know it is a reliable partner."(dpa, March 12, 2002)

The message is clear: Putin is no longer a security risk – but an economic option.

April 2002 – Gazprom on quiet feet

Parallel to Schröder's visit, confidential talks begin in Berlin between Gazprom subsidiary Gazexport, BASF, the Federal Ministry of Economics, and selected legal advisors. The subject: long-term gas supply contracts with terms of up to 30 years. It is the first technical outline of what will later develop into a "strategic partnership."

Wolfgang Clement, then Super Minister for Economics and Labor in Schröder's cabinet, notes in a memo with Aleksei Miller (then the new head of Gazprom) that "a technical connection between German markets and Russian sources is highly attractive from an economic perspective."

What is described here at the ministerial level as a "connection" is in reality the development of energy dependence.

June 2002 – G8 summit in Canada

The G8 summit takes place in Kananaskis, Canada. In the run-up to the summit, Schröder advocates greater integration of Russia into economic forums. Although Moscow officially only has guest status, Berlin actively works behind the scenes to secure Russia's permanent inclusion in G8 formats – against resistance from the US and the UK.

Joschka Fischer, then head of the Foreign Office, remains skeptical but supports the course. Internally, an official notes in the Foreign Office minutes:

"The federal government is pursuing a long-term course of political normalization with Russia through economic integration."(Internal Foreign Office memo, quoted in: FAZ reconstruction from 2018)

In the summit communiqué, Russia is then described for the first time as an equal economic partner – a symbolic act, but one with enormous political significance.

July–September 2002 – Exchange of elites

In the summer months of 2002, the German-Russian exchange machinery gets rolling:

The

German-Russian Raw Materials Forum

is founded with the help of the Committee on Eastern European Economic Relations.

Numerous foundations with links to the SPD (Friedrich Ebert Foundation, Friedrich Naumann Foundation) begin to develop cooperation formats with Russian think tanks.

In the federal states (especially

Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania

,

Brandenburg

, and

Lower Saxony

), initial talks began on possible industrial and energy settlements with Russian participation.

Schröder, Steinmeier, Gabriel – they are all regularly cited as "bridge builders," "voices of reason," and "mediators between East and West." In reality, a network is emerging that elevates proximity to Moscow to a political project.

October 2002 – Gerhard Schröder in St. Petersburg

On the sidelines of an EU-Russia summit in Saint Petersburg, Schröder meets Putin again. In confidential talks, they discuss the possibility of direct gas deliveries bypassing "unstable transit countries," as diplomatic dispatches later reveal. They are referring to Ukraine and Poland.

These talks are the conceptual nucleus of Nord Stream 1 – and they are not taking place at the EU level, but rather as a bilateral initiative.

Political reactions in Germany: none

In 2002, there was no substantial debate in the Bundestag or among the opposition about Germany's new Russia strategy. There were no hearings, no critical assessment of the energy talks, and no systematic risk analysis.

Instead, German-Russian relations are conducted under the label of "normalization" – a term that conceals a great deal and explains very little.

The year 2002 is a turning point. Not because something explodes, but because everything quietly solidifies: the rhetoric, the closeness, the network.

Putin is courted by Schröder, not scrutinized.

Gazprom does not act as a political player, but as a supposed market player.

The opposition remains silent because dialogue with Moscow is considered common foreign policy.

Germany builds bridges—politically and economically—to an authoritarian system. And it does so with a calm voice, a smile, and its eyes wide open.

Chapter 2 – Section 2.3

2003: The Khodorkovsky case – How Russia disciplined its oligarchs and Germany remained silent

"In Russia, you can be rich – but not independent."— Mikhail Khodorkovsky, February 2003

I. Who was Khodorkovsky?

Mikhail Borisovich Khodorkovsky – born in Moscow in 1963, son of an engineer, member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union until 1991, chemist, software developer, later financial manager. He was one of many young men who turned the economic ruins after the collapse of the Soviet Union into money – a lot of money.

But unlike many other oligarchs of the time – including Abramovich, Berezovsky, and Deripaska – Khodorkovsky was different: he believed in Western principles.

He wasn't just rich – he was educated, ambitious, and Western-oriented. And he wanted influence.

II. Yukos – The Empire

In the 1990s, Khodorkovsky took over the ailing Soviet oil company Yukos in one of the infamous "loans-for-shares" deals organized under Yeltsin. He acquired a majority stake for a fraction of the value – and turned Yukos into one of Russia's most modern and transparent energy companies.

Introduction of Western accounting

Collaboration with McKinsey & Co

Stock market listing and international joint ventures

Disclosure of ownership structures

At the same time, Khodorkovsky began to establish contacts in the US and Europe with the aim of merging Yukos with an American or British oil company. Negotiations with ChevronTexaco and ExxonMobil were already in full swing in 2002.

This was a thorn in Vladimir Putin's side.

III. February 2003 – The famous scene in the Kremlin

During a meeting in the Kremlin, broadcast on Russian television, the moment that is considered the turning point occurs.

Khodorkovsky publicly confronts Putin with a dossier on corruption in the state-owned oil company Rosneft. He speaks openly about bribery, black money, and officials with offshore accounts. Putin, visibly stunned, replies:

"I would advise you to mind your own business."

What would have been legitimate discourse in a Western democracy was a death sentence in Putin's Russia – politically, economically, and later also legally.

IV. October 2003 – The arrest

On the morning of October 25, 2003, Khodorkovsky's private jet lands at the airport in Novosibirsk. He is on his way to a business meeting in the Siberian oil region. While still on the tarmac, masked men from the FSB (the successor to the KGB) storm the plane, handcuff him, and take him directly to Moscow – without a court order or formal charges.

The charge: tax evasion – later supplemented by fraud, money laundering, and embezzlement.

In reality, however, it was a political move – a signal: anyone who opposes Putin's vertical power is not warned, but removed.

V. The trial – a show trial

The first trial began in Moscow in 2004. The judges were young and intimidated, and the prosecution had a thin case file – but a clear mission.

Khodorkovsky is paraded in a glass cage, and the image is seen around the world: Russia's most modern oligarch – like a criminal in a cage.

The end result: nine years in prison, exile to Siberia.His company Yukos is broken up – the prime assets are taken over by Rosneft, a state-owned company with close ties to the Kremlin, led by Igor Sechin, Putin's close confidant.

VI. German reactions: cautious to non-existent

In the Federal Chancellery under Frank-Walter Steinmeier, the case is classified internally as a "Russian judicial matter." Schröder says nothing publicly – unofficially, it is said that they do not want to strain relations with Putin.

J

oschka Fischer is critical of the "nature of the public spectacle," but his comments are nothing more than empty phrases. An official condemnation? None.

German business leaders – including BASF, Wintershall, and Siemens – do not distance themselves, but signal that "business continuity is not affected."

VII. The role of the EU – a shadow

Brussels is also reacting hesitantly. Although the EU Parliament has expressed "concern" about the proceedings, there are no sanctions or political steps.

Why?

Because Yukos was not European

Because Russia was needed as an energy supplier

And because Khodorkovsky, as an oligarch, never received the sympathy that dissidents such as

Navalny

later did

VIII. What really happened

Khodorkovsky's arrest was not just a personal tragedy – it was a signal from the system:

The Russian state does not tolerate any economic power base outside the Kremlin

Companies with a commitment to transparency and a Western orientation are a risk

Critics, even if they grew up loyal to the system, are eliminated

It was the birth of Putinism 2.0 – the merging of state, power, security apparatus, and raw materials economy under absolute control.

IX. And Germany?

Germany could have made this moment a turning point – politically, economically, and morally.

But instead, the opposite happened:

2004

: Schröder calls Putin a "flawless democrat."

2005

: The idea of Nord Stream takes shape

2006

: German companies increase their investments in Russia

Putin's lesson: You can arrest an oligarch, break up a billion-dollar company, undermine the rule of law – and the West will do nothing.

Conclusion: Section 2.3

The Khodorkovsky case was not an internal power struggle, but a global signal. Russia under Putin had made its choice: autocracy, isolation, concentration of power.

Germany, Europe, the West – should have recognized this.They should have responded.

But they responded with silence.

Chapter 2 – Section 2.4

2004: The school of violence – Chechnya, Beslan, and Schröder's "flawless democrat"

"He is a flawless democrat."— Gerhard Schröder on Vladimir Putin, 2004

I. Russia in war mode – The shadow of Chechnya

In the spring of 2004, the Second Chechen War was raging in the North Caucasus. Officially, it had been declared over in 2000 – but in reality, the Russian state under Putin was waging a merciless war of occupation against any form of resistance in the region.

Satellite images from Grozny show a city that is more rubble than settlement. Human rights organizations such as Memorial, Human Rights Watch, and the Council of Europe speak of

systematic torture in "filtration camps"

the disappearance of opposition figures

use of heavy artillery against residential areas

extrajudicial executions by Russian special forces

The Russian central government calls this "anti-terrorist measures."Vladimir Putin speaks of "stabilization through strength."

II. The Beslan massacre

On September 1, 2004, 32 armed men—presumed to be Chechen separatists—occupy Primary School No. 1 in Beslan (North Ossetia). They take over 1,100 hostages, including nearly 800 children.

The Russian government decides on a military solution.

On the third day, without prior negotiations, Russian special forces storm the school building with rocket-propelled grenades and machine guns. The result is catastrophic:

334 dead

, including

186 children

Chaotic command and control

Firefights that remain unexplained to this day

Blocked aid corridors, no transparency regarding causes of death

Putin subsequently speaks of a "victory against terror."The mothers of the children killed in Beslan form a citizens' initiative – to this day, they are monitored and, in some cases, threatened in Russia.

III. The German reaction: a quote that sticks

Shortly after the massacre, Gerhard Schröder gives an interview to the Hamburger Abendblatt. The question: How does he assess Russia's development, also in view of Chechnya and Beslan?

His answer:

"Putin is a flawless democrat."— (Hamburger Abendblatt, November 23, 2004)

It is a sentence that burns itself deeply into the memory of the republic, but also into the record of German policy toward Russia.

Whether Schröder said it deliberately provocatively or out of strategic loyalty remains unclear. One thing is certain: he never took it back.

IV. Frank-Walter Steinmeier – architect of silence

As head of the Federal Chancellery, Frank-Walter Steinmeier is the central foreign policy coordinator of the federal government during this phase. All Russia-related issues cross his desk. Minutes from the Foreign Office, later published by Wikileaks, show that there were internal reports of human rights violations in Chechnya.

A memo from the Russia department (AA, Department 206) dated October 2004 warns:

"The violence in Chechnya has taken on systemic characteristics. The security forces are operating outside the framework of the rule of law."– (AA, internal memo, quoted in Süddeutsche Zeitung, 2013)

The reaction of the Chancellor's Office: none.

The memos were noted but not turned into policy.

V. SPD and foreign trade: no change of course

Despite the events in Beslan and Chechnya, there has been no break in economic relations:

The German Committee on Eastern European Economic Relations is sticking to its Russia agenda

BASF and Wintershall are intensifying their contacts with Gazprom

Siemens and MAN are supplying infrastructure components

Sigmar Gabriel, then SPD secretary-general, speaks publicly of a "responsible foreign policy with Russia on an equal footing."

In the federal states, too, SPD-led state governments – including in Brandenburg, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, and Lower Saxony – begin to establish cooperation with Russian energy partners.

VI. Merkel remains silent – but observes

At this time, Angela Merkel is the leader of the opposition in the Bundestag. In September 2004, she comments cautiously on the Beslan massacre, calling Putin's handling of the situation "worrying" but avoiding any direct criticism.

Her foreign policy spokesman, Friedbert Pflüger, said:

"We must not isolate Russia, but we must not accept everything either."

The "but" remains.

VII. The media – debate without effect

Beslan is an outcry in the arts pages.

The

Frankfurter Allgemeine

speaks of a "state crime without admission of guilt."

Die Zeit

headlines:

"Russia's war on children."

The

taz

calls Putin's Russia "a controlled democracy with a license to use violence."

But at the political level, the impact fizzles out.The debate remains in the arts pages—no sanctions, no official resolution in the Bundestag, no breaking off of talks with Moscow.

VIII. Vladimir Putin – strengthened by the silence

In a press conference after Beslan, Putin stands up and says:

"The Western world has no moral right to point the finger at us."

This attitude remains Putin's standard formula to this day:Violence is part of the order – anyone who criticizes it does not know Russia.

And Germany?

It conforms. It continues to seek understanding, agreements, a way of dealing with Putin – not on the basis of values, but on the basis of interests.

2004 was a year in which Russia made its authoritarian line unmistakable:

war in Chechnya

massacre in Beslan

systemic violence under Putin's command

And Germany?

Gerhard Schröder calls the man at the top a

"Flawless democrats."

Frank-Walter Steinmeier takes note of this—and does nothing.

The economy cooperates. The media criticizes. Politicians remain silent.

It is the year in which it should have been possible to recognize that Putin's Russia is not a partner – but a system that does not tolerate dissent.

It could have been recognized.If one had wanted to.

Chapter 2 – Section 2.5

2004: The Orange Revolution – and Germany's maneuvering between Kiev and Moscow

"Those who want to be rewarded with peace in Moscow must remain silent in Kiev."— (internal comment from the State Department, anonymized, 2005)

I. A country between two worlds

In the fall of 2004, Ukraine stands at a crossroads.Presidential elections are scheduled for October 31 and November 21, but what should have been a democratic transfer of power turns into a political showdown. On one side is the pro-Russian candidate Viktor Yanukovych, supported by the Kremlin and openly backed by Putin. On the other is Viktor Yushchenko, Western-oriented, pro-European, and supported by civil society movements, student groups, farmers, and trade unions.

In the weeks leading up to the runoff election, events come thick and fast:

Yushchenko is poisoned with dioxin on September 5.

His face is disfigured; an assassination attempt is suspected.

Russian media defamed him as a CIA puppet.

The Kremlin sends "election observers" who turn out to be political agents of influence.

On November 22, Yanukovych is declared the winner through electoral fraud.

II. The uprising begins

Within hours, hundreds of thousands of people gather in Kiev's central Maidan Square. It is the beginning of the "Orange Revolution" – a mass movement led by students, pensioners, intellectuals, and veterans. They demand:

A recount of the votes

Resignation of the Central Election Commission

EU observers

Free and fair new elections

The images are broadcast around the world: thousands of tents on Maidan Square, improvised stages, speeches in the snow, chains of lights, folk songs. The Ukrainian flag flies alongside orange banners – a symbol of hope and resistance.

III. Moscow's reaction – and Putin's interference

Vladimir Putin congratulates Yanukovych on his victory on the night of the controversial runoff election – before the international election observation mission has given its assessment.

Putin's message:"Ukraine belongs to Moscow's sphere of influence."

Plans for a closer customs union, energy dependence, and economic integration are already circulating in Moscow. From the Kremlin's point of view, Ukraine should not become a bridgehead for the West.

IV. Germany reacts: cautiously, hesitantly, diplomatically

At this point, Joschka Fischer is still foreign minister, but the line is increasingly being set by the chancellor's office under Frank-Walter Steinmeier. Officially, the German government calls for "restraint on all sides" and "respect for democratic processes."

Gerhard Schröder does not comment directly on the allegations of fraud.Instead, in an interview with the FAZ (November 28, 2004), he emphasizes:

"The stability of the region must not be jeopardized by hasty political intervention."

Between the lines: they don't want to upset the Kremlin.

V. Frank Walter Steinmeier – The balance manager

At Schröder's request, he organizes the so-called "troika solution": negotiations between Russia, Ukraine, and the EU. It is a diplomatic balancing act that seems clever at first glance, but in reality is a strategy of delay.

An internal memo from the Foreign Office, later made public by Wikileaks:

"The German government's position is based on the premise that strategic reliability toward Moscow takes precedence over public partisanship for Kiev."— AA Russia Department, confidential, Dec. 2004

The US, on the other hand, positioned itself early on on Yushchenko's side.Condoleezza Rice and Colin Powell speak of a "test case for European democracy."

Germany, however, remained silent. And took action.

VI. The West looks on – Berlin vacillates

While hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians endure the snowstorm, the German Federal Ministry of Economics sends out invitations to a conference for investors in Russia in Frankfurt. BASF and Siemens are attending, as is Wintershall. No one wants to risk political solidarity with Kiev provoking economic retaliation from Moscow.

Joschka Fischer finally travels to Kiev – late.

He meets with Yushchenko, Yanukovych, and representatives of the opposition. But his words remain vague. No open accusations. No solidarity in the media. Just one sentence:

"The European Union is monitoring the situation with the utmost attention."

A sentence tailor-made for diplomatic evasion.

VII. The Constitutional Court decides – the protests win

On December 3, 2004, the Ukrainian Constitutional Court declares the runoff election invalid. The election is repeated on December 26.Viktor Yushchenko wins – under international observation.

The "Orange Revolution" prevails – not because of European support, but despite European hesitation.

The assassination attempt – how Yushchenko's face became a political message

"They didn't want to stop me. They wanted to disfigure me – to show what happens when you rebel."— Viktor Yushchenko, BBC interview, 2005

I. The eve of terror

September 5, 2004, Kiev.Viktor Yushchenko is invited to dinner – informal, supposedly confidential, supposedly harmless. The host: Ihor Smeschko, then head of the Ukrainian secret service SBU, a man with close ties to Moscow.

Also present: Volodymyr Satsyuk, deputy head of the SBU, a figure who would later find himself at the center of international investigations.

While still at the table, Yushchenko feels the first signs: headaches, nausea, blurred vision. Hours later, he collapses.

II. The diagnosis: dioxin

Within a few days, Yushchenko's condition deteriorates dramatically:

his face swells grotesquely

his skin becomes scarred, his left eye droops

his liver and pancreas almost completely fail

The case is investigated at the Rudolfinerhaus Clinic in Vienna. After months of tests, the diagnosis is clear:

dioxin poisoning – 1,000 times above the permissible limit

Such a level is no accident – it is planned.And it is a signature. Not murder, but a lifelong warning.

III. What dioxin means

Dioxin rarely kills immediately – it is not an agent for assassins in a hurry. It is a political poison. Its effects are slow, painful, visible. It disfigures the face – and that is exactly what it is intended to do: create a memorial.

The enemy lives – but he is marked.He carries his punishment with him, in the mirror, in the media, on every election poster.It is psychological warfare using chemical means.

IV. Putin's line of control

Russia denies any responsibility.But Western intelligence agencies and investigative journalists – including Der Spiegel, the BBC, and Radio Free Europe – suggest that

The substance used was

highly purified TCDD

– which can only be produced in special laboratories.

Access to this substance was only available in

state or military facilities

Volodymyr Satsyuk

, the host of the dinner,

went into hiding in Moscow shortly after the assassination attempt

Russia has refused to extradite Satsyuk to this day

The suspicion: The assassination was not a spontaneous attempt by the Ukrainian government, but part of a coordinated intelligence operation with the acquiescence – if not the direction – of Moscow.

V. The international reaction: shock and silence

The attack causes horror around the world.

Tony Blair speaks of a "moral low point in the post-Soviet space."

George W. Bush calls the attack "an affront to all who want democracy."

And Germany?

Gerhard Schröder does not comment.

Frank-Walter Steinmeier speaks internally of "a regrettable escalation."

Joschka Fischer avoids direct accusations and emphasizes "the complexity of the situation."

Restraint prevails, even though a man has been publicly poisoned—on the orders or with the tacit approval of forces with which Berlin continues to negotiate agreements.

VI. What the assassination really revealed

The assassination attempt was not just an attack on Yushchenko.It was a demonstration of strategic cruelty. A message to Ukraine, to Eastern Europe, to the West:

Anyone who opposes the Kremlin will not simply be fought politically—they will be deformed.

It was Putin's signature before the world was ready to recognize it.

VIII. Looking back: a missed opportunity

Germany could have set the tone with clear words, an active diplomatic offensive, and economic pressure on Moscow—not against Russia, but for democracy.

But it remained stuck in a state of indecision.

Because the gas talks with Gazprom were ongoing

Because Schröder and Putin did not want to alienate each other

Because Steinmeier was committed to stability

And because Ukraine was not seen as a key geopolitical country – but as a disruptive factor in relations with Moscow

The Orange Revolution was a turning point – for Ukraine, for Europe, for Russia.

But Germany was not on the Maidan, but on the Kremlin phone.

While thousands fought for freedom, Berlin stuck to the principle of non-interference – a principle that in reality legitimized Moscow's interference.

E

It was the year that showed thatWhen forced to choose between democracy and a gas pipeline, Berlin often chooses the pipeline.

Chapter 2 – Section 2.6

2005: Schröder's departure – and the quiet transition to Moscow

"I have made my decision. And I know why."— Gerhard Schröder on criticism of his work for Gazprom (2006)

I. The end of a chancellorship

The vote of confidence – Schröder's calculated departure

"I am calling for a vote of confidence because I no longer see the support of the majority."— Gerhard Schröder, July 1, 2005

I. The political background

Spring 2005: The red-green federal government is under pressure. The SPD is losing one state election after another. Unemployment is over 5 million. The reform policies of Agenda 2010 are dividing its own electorate. In North Rhine-Westphalia, once an SPD stronghold, the party loses the state election in May 2005 – a symbol of the nationwide loss of confidence.

Gerhard Schröder realizes that political support in the country has been exhausted.

But instead of resigning or muddling through in office, he plans a bold move – under controlled conditions.

II. The idea: bringing about new elections

The Basic Law only provides for new elections if the Bundestag withdraws its confidence in the chancellor – or if the chancellor himself calls for a vote of confidence and loses. This is exactly what Schröder is aiming for.

On July 1, 2005, he calls for a vote of confidence in the Bundestag. He does not link it to a specific decision, but to a political assessment:

"I am convinced that this coalition is politically exhausted."

A remarkable move: the chancellor is asking his own parliament not to confirm him – in order to force new elections.

III. Controlled loss of control

In the run-up to the vote, the SPD parliamentary group votes tactically:

Some members of parliament abstained from voting

Others deliberately vote "no."

The Greens go along with it

The result: The chancellor loses by 151 votes to 296.

The stage is set for new elections.

A clear political signal—but also a legally questionable maneuver, because the Basic Law requires a genuine loss of confidence, not tactical maneuvers.

IV. The Federal Constitutional Court – and its ruling

Two members of the Bundestag file a lawsuit against the dissolution of parliament: former CDU member Werner Schulz and lawyer Johann Lang.

The Federal Constitutional Court hears the case on August 25, 2005. The ruling is handed down at 10 a.m. on August 25:

"The Federal President has discretion in assessing the loss of confidence."— BVerfG, 2 BvE 4/05

In other words: Schröder's maneuver is permissible—both politically and legally.

V. Why this phase is decisive

Between July and September 2005, a temporary power vacuum opens up: Schröder is chancellor, but no longer unchallenged. During this transitional period,

he did not introduce

any strategic legislative initiatives

travels to

Moscow and Sochi several times

– among other things for an informal exchange with Putin

he is

more politically free than ever before

, but

below the media radar

These weeks mark the beginning of the secret preparations for Nord Stream – it is precisely during this phase that Schröder's political influence is monetized.

VI. The moral question

The problem was not the legal legitimacy of the vote of confidence.The problem was what Schröder did with this political loophole.

He used the period between the vote of confidence and the election defeat to set economic and strategic courses that served his future employer.

He traveled – as has been proven – to Moscow in the summer of 2005, where he met with Gazprom boss Alexei Miller and Putin, while still chancellor.

The vote of confidence was not an act of desperation – it was a calculated power play with which Schröder paved his way out of politics without taking responsibility.

He lost – but on his own terms.He stepped down – but remained at the table.

And while the country believed that a chapter had been closed, he was already preparing the next one in Moscow.

On September 18, 2005, Gerhard Schröder lost the federal election to Angela Merkel. It was an extremely close election: the CDU/CSU won 35.2% of the vote, the SPD 34.2%. The parties spent weeks negotiating possible coalitions, with Schröder initially claiming the office for himself in a last-ditch effort. But in the end, he had to give up.

On November 22, 2005, Schröder hands over the chancellorship to Merkel.Frank-Walter Steinmeier becomes foreign minister, Peer Steinbrück finance minister.

The Schröder era is officially over.

What hardly anyone knows at this point, however, is that preparations are already well underway for one of the most controversial post-chancellor careers in German history.

VII. The letter from Moscow

Just a few weeks after the election, a confidential letter arrives at the Federal Chancellery:

Gazprom subsidiary North European Gas Pipeline Company (NEGP) announces its intention to appoint a prominent European chairman of the supervisory board for the Nord Stream project, which is currently under construction – preferably Gerhard Schröder.

Officially, it is a "proposal."

In reality, it is a political agreement between Vladimir Putin and Schröder that dates back to the summer of 2005, while Schröder was still in office.

The letter is not made public.

Instead, initial talks begin between Gazprom, Schröder's lawyers, and the German chancellor's office – now under Merkel's leadership.

The letter – Schröder's appeal from the Kremlin

"The offer came as no surprise – it had been prepared."

I. The letter – and its true story

The letter from Moscow that arrived at the Chancellery in November 2005 was not merely an invitation, but a political statement. Sender: Gazprom via the NEGP Company (North European Gas Pipeline), based in Zug, Switzerland. Contents: A request for approval of Gerhard Schröder's appointment as chairman of the supervisory board of the pipeline company.

But this letter was not the beginning, but rather the end of a process – and this process did not begin after Schröder's departure, but rather in the middle of his chancellorship, presumably between spring and summer 2005.

What is known today – based on research by Spiegel, Süddeutsche Zeitung, Correctiv, and statements by those involved – paints the following picture:

Schröder and Putin

agreed back in spring 2005

that the strategic management of the Nord Stream project had to be secured not only technically but also politically.

Schröder was

involved in developing the financing concept

, including German guarantees and credit lines through KfW-affiliated institutions.

The letter in November was

not an application – it was confirmation of a deal

that had long since been decided.

II. Political context: Back channel to Moscow

What looks like an "offer" was in fact a reward for political efforts made in advance:

Schröder had

campaigned heavily for Nord Stream 1

, against Eastern European protests and internal concerns.

In the Bundestag, he had always described the project as "economically necessary" – even though everyone knew that it

was geopolitically motivated

.

He had blocked

any debate

on alternatives (e.g., LNG terminals, transit routes via Poland).

And he had played a key role in shaping

the legend of the "strategic partnership with Russia

.

"

Putin's Russia thanked him with a highly remunerated post, access to Russian networks, personal proximity, and international visibility.

III. Did Russia want to buy influence?

Yes. And it succeeded.

What we know today:

Gazprom was

not just a corporation

– it was an

instrument of power for the Kremlin

, controlled by Putin's close confidants, above all

Alexei Miller

and

Igor Sechin

.

The Nord Stream project was

strategically motivated

: to bypass Ukraine, divide Europe, and achieve bilateral dominance over Germany.

Schröder as chairman of the supervisory board meant that