Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

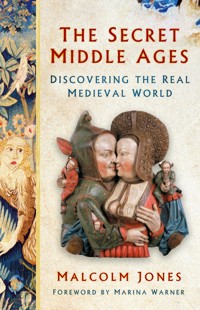

The Middle Ages are known as a god-fearing time, a time of hard work and of squalid living conditions for the majority of the population – or as a time of opulence that graced only the courts and halls of the reigning monarch. In The Secret Middle Ages, Malcolm Jones presents a completely fresh view of the medieval world that will blow all stereotypes out of the water. Using a wealth of little-known and recently discovered artefacts, and drawing particularly on humbler artworks, Jones paints a compelling picture of the visual environment of the great mass of ordinary people between 1200 and 1550. The picture that emerges is of a civilisation that is both like and unlike our own – one that teems with the richness of life and its contradictions. We find beliefs and traditions rendered memorable by the vivid, creative imagination and strong visual culture of the Middle Ages. Love, hatred, crime and punishment, proverbs, heaven on earth, husband-beating – all feature in the jewellery, tableware, illustrations, carvings and textiles of the period. A major reassessment of the high medieval period, this revised and updated edition of The Secret Middle Ages is essential reading for anyone curious about their ancestors. As Jones writes, gems and precious metals may dazzle the eye, but a pewter brooch – tawdry as it may appear – has the power to reveal far more of the real medieval world.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 1097

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For my parentsand all my other teachers

Cover illustrations: centre: Fool embraces woman: painted wooden towel-rail, Arnt van Tricht, Kalkar, 1530s (© Museum Kurhaus, Kleve: photograph courtesy of Annegret Gossens) left: Der Busant: tapestry fragment, Strasbourg, late 15thC. (© Metropolitan Museum of Art)

First published 2002

This updated and revised edition first published 2025

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Malcolm Jones, 2002, 2025

The right of The Author to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 901 2

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

Contents

List of Illustrations

Foreword to the 2025 Edition

Foreword to the 2002 Edition

Preface

Acknowledgements

Conventions and Abbreviations

ONE

Love, Death and Biscuits

TWO

Magical Metal, Silly Saints and Risible Relics: The Art and Artefacts of Popular Religion

THREE

Licked into Shape: Animal Symbolism

FOUR

Why Englishmen Have Tails: The Iconography of Nationality and Race and the Uses of Monstrosity

FIVE

Signs of Infamy: The Iconography of Humiliation and Insult

SIX

The Fool and the Attributes of Folly

SEVEN

Shoeing the Goose: The Representation of Proverbs and Proverbial Follies in Art

EIGHT

Nonsense, Pure and Applied

NINE

Narratives – Heroic and Not So Heroic

TEN

Hearts and Flowers and Parrots: The Iconography of Love

ELEVEN

Who Wears the Trousers: Gender Relations

TWELVE

Wicked Willies with Wings: Sex and Sexuality in Late Medieval Art and Thought

THIRTEEN

Tailpiece: The Uses of Scatology

Conclusion

Notes and References

Ça rime commehallebarde et miséricorde

Hit nys nout as men wenet

List of Illustrations

Figures and Ornaments

Ornament to half-title and pages v, vi, xiv, xxii, xxv, 295, 300, 366: bronze roundel with enamelled inscription, hyt nys nout as men wenet, English, ?15thC. (Present whereabouts unknown: photograph © The British Museum)

Ornament to Chapter 1: elderly man in bath with young woman fool: lead lid, ?Dutch, 15thC. (Photograph courtesy of Brian Spencer)

1.1 Lovers (woman naked) beside fountain: cast of biscuit-mould, German, first half 15thC. (© Städtisches Museum in Andreasstift, Worms)

1.2 Lovers (woman naked) seated on bed playing instruments: cast of biscuit-mould, German, first half 15thC. (Museum Wiesbaden)

1.3 Man threshes chicks out of eggs: misericord, Emmerich, late 15thC. (Photograph courtesy of Elaine Block)

1.4 All ride the ass: woodcut, German, early 16thC. (Bodleian Library, Oxford, Douce Prints W.2.2b (25). Photograph from E. Diederichs, Deutsches Leben der Vergangenheit, Abb. 666, Jena, 1908)

1.5 Fox/wolf preaches to sheep: stained and painted glass, English mid-15thC. (© Burrell Collection, Glasgow)

1.6 Dildo-pedlar (and dog running off with one): cast of biscuit-mould, German, first half 15thC. (© MAK Österreichisches Museum für Angewandte Kunst, Vienna)

Ornament to Chapter 2: four-leaf clover inscribed ‘t’: lead badge, English 14th/15thC. (Photograph courtesy of Brian Spencer)

2.1 Christ-child caressing parrot with New Year’s greeting: woodcut-sheet, German, mid-15thC. (© Staatlichen Museen Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin)

2.2 St Gertrude and mice: woodcut-sheet, German, mid-15thC. (© Staatlichen Museen Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin)

2.3 Quatrefoil replaces head of God the Father: manuscript miniature, English, early 13thC. (By permission of the Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge. Ref: Trinity College Library, MS B.11.4, f. 119r)

2.4 St Werburgh’s geese in pen: misericord supporter, Chester Cathedral, late 14thC. (© University of Manchester: photograph courtesy of Christa Grössinger)

2.5 Edward III as a boy and Queen Isabella: lead badge inscribed Mothere, English, c. 1330. (© The British Museum)

2.6 Manuscript map of the Isle of Thanet, showing detail of the deer and the cursus cerve, English, c. 1410. (Ref: MS 1, Trinity Hall, Cambridge)

2.7 Birds help St Alto build his cell: woodcut-sheet, German, c. 1500. (© National Gallery of Art, Washington)

2.8 Phallus, flanked by women, surmounts breeches: lead badge, Dutch, first half 15thC. (© Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum, Rotterdam: Stichting Middeleeuwse*)

2.9 Sinte Aelwaer: woodcut-sheet (detail), Cornelis Anthonisz, Amsterdam, c. 1520. (© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam)

Ornament to Chapter 3: Cat with mouse, inscribed gret wel gibbe oure cat: drawing of seal-impression. (Reproduced with permission of the Society of Antiquaries from Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries N.S. 12 (1888), p. 97)

3.1 The king of the Garamantes rescued by his dogs: manuscript miniature (detail), English, 1220s/1230s. (© The British Library. Ref: BL, Royal MS 12. F. XIII, f. 30v)

3.2 Mattathias beheads the idolatrous cat-worshiper: manuscript miniature (detail), Winchester Bible, f. 350v, English, late 12thC. (Photograph © Winchester Cathedral)

3.3 Four proverbs enacted before King David: engraved sheet, Van Meckenem, c. 1495. (© The British Museum)

3.4 Turning the cat in the pan: pen-and-ink marginal drawing, Muschamp Moot Book, English, early 15thC. (© The British Library. Ref: BL, Harl. MS 1807, f. 309)

3.5 Misericord: rat-porteur/rapporteur, Vendôme, late 15thC. (Photograph courtesy of Elaine Block)

3.6 Animals in roundels: engraved sheet (detail), Florence, c. 1460. (© The British Museum)

3.7 Emblematic catechism: woodcut-sheet, Tegernsee, late 15thC. (© Bibliothèque nationale, Paris)

3.8 Bronze tap with handle in the form of a cockerel, English 15thC. (Private collection: photograph courtesy of Brian Spencer)

3.9 Sex organs in intercourse: seal-impression from matrix found at Wicklewood, inscribed IAS: TIDBAVLCOC, English, c. 1300. (Drawing by Steven Ashley of Norfolk Landscape Archaeology)

3.10 amulet in the form of the valves of a mussel, one inscribed with vulva symbol, Dutch, 1375x1425. (© Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum, Rotterdam: Stichting Middeleeuwse*)

3.11 Young woman and fox: pen-and-ink drawing, South German, c. 1530. (© Universitätsbibliothek Erlangen-Nürnberg)

3.12 Wife beats yarn-winding husband with foxtail: brass dish, German, late 15thC. (© Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

3.13 Gold finger-ring, engraved with woman leading squirrel and a figura grammatica inscription, English, 15thC. (© The British Museum)

3.14 Flock in sheep-fold with bell-wether: manuscript miniature, Luttrell Psalter, English, c. 1330x40 (© The British Library. Ref: BL, Add. MS 42130, f. 163v)

Ornament to Chapter 4: devil as fashionably-dressed woman: manuscript miniature, Winchester Psalter, English mid-12thC.

4.1 Head-on-legs monster (blemya): misericord supporter, Ripon, late 15thC. (Photograph: author’s collection)

4.2 Wild Men and dragons: misericord, St Mary’s, Beverley, mid-15thC. (Photograph: author’s collection)

4.3 Tailed king hawking: manuscript miniature, Picardy, late 13thC. (© Yale University. Ref: MS 229, f. 363r)

4.4 Bridegroom with cuckold’s horns: manuscript miniature, Decretals, French, c. 1300. (© Bibliothèque nationale, Paris. Ref: BN MS lat. 3898, f. 297)

4.5 Master and schoolboys, dunce wears ass’s head: woodcut, Spiegel des menschlichen Lebens, Augsburg, 1470s. (© Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich)

4.6 Clerical wolves devour sheep: title-page woodcut, Wie man die falschen prophete, Wittenberg, 1536. (© Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich)

4.7 Wineskin-monks sing in praise of vino puro: misericord, Ciudad Rodrigo, c. 1500. (Photograph courtesy of Elaine Block)

4.8 Medieval stone sheelagh-na-gig, Llandrindod. (Photograph: author’s collection)

4.9 Picture of Nobody: title-page woodcut, Sermo pauperis Henrici de sancto Nemine, German, c. 1510. (© Staats- und Stadtbibliothek, Augsburg,)

Ornament to Chapter 5: gagged scold’s head: misericord, Stratford-on-Avon, 15thC. (Photograph: author’s collection)

5.1 Nemo with bird nesting on head swats fly-swarm: title-page woodcut (detail), Leipzig, 1518. (© The British Library)

5.2 Allegory of penitence with fly-swarm: manuscript leaf, Lambeth Apocalypse. (© Lambeth Palace Library, London. Ref: MS 209, f. 53.)

5.3 Carvers quarrelling, one thumbs nose at his opposite number: misericord. (© University of Manchester: photograph courtesy of Christa Grössinger)

5.4 Debtor’s seal soiled with dung of sow on which man sits backwards, debtors hanged and broken on the wheel: painted manuscript Schandbild. (© Hessisches Staatsarchiv, Marburg)

5.5 Judensau: woodcut-sheet, German, late 15thC. (© Historisches Museum, Frankfurt)

5.6 Punishment of dishonest baker and prostitute: painted initial. (© Bristol City Council. Ref: Bristol City Charter 1347)

5.7 Dishonest ale-wife carried off to hell: misericord, Ludlow, c. 1420. (© University of Manchester: photograph courtesy of Christa Grössinger)

5.8 Old maid leads apes into hell-mouth: misericord, Bristol, 1520. (© University of Manchester: photograph courtesy of Christa Grössinger)

5.9 Man masquerading as washerwoman exposed in a cart at the crossroads: manuscript miniature, Cent nouvelles nouvelles, French, ?1462. (© Glasgow University Library. Ref: Hunter MS 252, f. 108r)

5.10 Devil barrows fox and monks to hell: misericord, Windsor, c. 1480. (Photograph courtesy of the Dean and Canons of Windsor)

Ornament to Chapter 6: fool’s head in eared hood: stall-elbow (detail), Beverley Minster, 1520. (Photograph: author’s collection)

6.1 Bench-end, fool holding ladle, St Levan, late 15thC. (Photograph: author’s collection)

6.2 Entertainer (?fool) in checked tunic with performing dog: manuscript miniature, Luttrell Psalter, English, c. 1330x40. (© The British Library. Ref: BL, Add. MS 42130, f. 84)

6.3 Bronze marotte head: Ellesmere, 15thC. (Rowley’s House Museum, Shrewsbury)

6.4 Male and female fools: engraving, Hans Sebald Beham, 1530s. (© The British Museum)

6.5 Fool’s head: ceramic whistle, English, 15thC. (© The British Museum)

6.6 Fool plays on penis, pig on bagpipe: manuscript drawing (detail), English, 14thC. (© The British Library. Ref: BL, Sloane MS 748, f. 82v)

6.7 a and b Fools in hood with (a) ear and belled peak, (b) ear and foxtail: stall-elbows, Manchester, c. 1506. (Photograph: author’s collection)

6.8 Grimacing fool’s head flanked by geese: misericord, Beverley Minster, 1520. (© University of Manchester: photograph courtesy of Christa Grössinger)

6.9 Platter (Ambraser Narrenteller) painted with fool scenes, Rhenish, 1528. (© Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nürnberg)

6.10 Boy bishop, lead seal matrix, 15thC, England. PAS database, LEIC-B9E481.

Ornament to Chapter 7: lead pendant in the form of a curry-comb inscribed fauel, English, 15thC. (Private collection: photograph courtesy of Brian Spencer)

7.1 Four proverbs (Proverbs 30, 18–19) and King Solomon: enamelled silver bowl roundel. (© St Annen-Museum, Lübeck)

7.2 Platter (Narrenschüssel) painted with enthroned king surrounded by sixteen proverbial follies, German, late 15thC. (© Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nürnberg)

7.3 Man thrashing ‘snail’ with flail: misericord, Bristol, 1520. (© University of Manchester: photograph courtesy of Christa Grössinger)

7.4 Man whipping snail: bronze fountain statuette, Flemish, mid-15thC. (Photograph © Sotheby’s)

7.5 Trying to squeeze a tree through a doorway crosswise: wall-painting, Mårslet, Denmark, late 12thC. (Photograph courtesy of Axel Bolvig, University of Copenhagen)

7.6 Humane rider at the windmill: Lead badge, Dutch, 1375x1425. (© Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum, Rotterdam: Stichting Middeleeuwse*)

7.7 Hare-messenger: stone statue, St Mary’s, Beverley, 13thC. (Photograph: author’s collection)

7.8 Man with wooden leg shears running hare manuscript miniature (detail), Bury Bible. (Photograph courtesy of the Courtauld Institute of Art. Ref: Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, MS 2, f. 1v)

7.9 Fools plant needles to grow steel bars: pen-and-ink drawing, Proverbes en Rimes, Savoie, late 15thC. (© Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore)

7.10 Washing the ass’s head: majolica dish, Deruta, 1566. (© Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

7.11 Shoeing the goose: misericord, Whalley, c. 1430. (© University of Manchester: photograph courtesy of Christa Grössinger)

7.12 Throwing the baby out with the bathwater: woodcut, Narrenbeschwörung, 1512.

Ornament to Chapter 8: winged boar: lead badge, English, ?15thC. (Private collection: photograph courtesy of Brian Spencer)

8.1. Priest ploughs, peasant celebrates mass in upside down church: woodcut, Spiegel der naturlichen himlischen und prophetischen sehungen, Leipzig, 1522. (© The British Library. Ref: BL, Sig. A4r)

8.2 Hare rides hound: floor-tile from Derby Priory, English, late 13thC. (© Pickford House Museum, Derby: photograph courtesy of Don Farnsworth)

8.3 Fool puts shoe on head: pen-and-ink drawing, Proverbes en Rimes, French, early 16thC., (© The British Library. Ref: BL, Add. MS 37527)

8.4 Winged pig on world-orb: woodcut sheet, Cornelis Anthonisz, Amsterdam, 1530s. (© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam)

8.5 Birds carry sacks to the mill: misericord supporter, Windsor, c. 1480. (Photograph courtesy of the Dean and Canons of Windsor)

8.6 Ass plays the organ: pen-and-ink drawing, Flemish, c. 1480. (© Ashmolean Museum, Oxford)

8.7 Knight fights snail: ivory draughtspiece, English, 14thC. (© The British Museum)

8.8 Hare spears tailor who drops shears: manuscript miniature, Metz Pontifical, Flemish, c. 1300. (© Fitzwilliam Museum. Ref: MS 298 f. 34v)

8.9 Threshing water: woodcut-sheet, Hans Sebald Beham, c. 1526. (© Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nürnberg)

8.10 Nous sommes sept: carved wooden group, French, ?early 16thC. (© Musée de la Chartreuse, Douai)

8.11 Ass in the tree, birds on the ground, low-relief wood carving,1521, Switzerland.

8.12 Apes rob pedlar, enamelled beaker, 1425x50, Burgundy. New York, Metropolitan Museum, 52.50.

8.13 Hare and hound gamble for hood, seal matrix (impression), 14thC, England.

8.14 Ape, owl, ass, copper alloy seal matrix (photo reversed), 14thC, England. PAS database, IOW-9975D3.

Ornament to Chapter 9: swan-knight: misericord, Exeter, c. 1240. (Photograph: author’s collection)

9.1 Guy of Warwick slays dragon and rescues lion: silver-gilt roundel in base of mazer bowl, English, 14thC., St Nicholas’s Hospital, Harbledown. (Photograph courtesy of The Royal Museum and Art Gallery, Canterbury)

9.2 Tristan and Isolde: lead mirror-frame, English, 13thC. (© Perth Museum and Art Gallery)

9.3 Ywain’s horse severed by portcullis: misericord, Enville, late 14thC. (© University of Manchester: photograph courtesy of Christa Grössinger)

9.4 The Man in the Moon: seal-impression, English, 14thC. (© Society of Antiquaries of London)

9.5 Moon as profile face: misericord, Ripple, late 15thC. (© University of Manchester: photograph courtesy of Christa Grössinger)

9.6 Lazybones, inscribed LEIIAERT: lead pendant, Dutch, 1375x1425. (© Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum, Rotterdam: Stichting Middeleeuwse*)

9.7 Le Bon Serviteur: woodcut-sheet, French, 1560s/1570s. (©Bibliothèque nationale, Paris)

9.8 Clever daughter: misericord, Worcester, 1379. (Photograph: author’s collection)

9.9 Fox hanged by birds: bench-end, Brent Knoll, late 14thC. (Photograph: author’s collection)

9.10 Wolf at school, earthenware tile, mid-13thC, Switzerland.

Ornament to Chapter 10: heart pinned to sleeved arm: lead badge, Dutch, 1325x75. (Gemeente, Dordrecht)

10.1 Youth suffering the pangs of love: dotted print, German, late 15thC. (© The British Museum)

10.2 Man with hand on skull holding pansy: oil painting on panel, Flemish, early 16thC. (© National Gallery, London)

10.3 Rose-bud labelled GENTIL BOTU: lead badge, French, 15thC. (Musée du Moyen Age, Cluny: photograph © Réunion des Musées Nationaux, courtesy Gérard Blot)

10.4 Riddle of seated woman and three suitors: pen-and-ink drawing, French, late 15thC. (© Cleveland Museum of Art)

10.5 Gold finger-ring ornamented with love-knot and padlock: German, 14thC. (© Museum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte, Lübeck)

10.6 Blindfold girl practises love-divination with book: engraving, Melchior Lorch, 1547. (© The British Museum)

10.7 Gold pendant from West Acre, ornamented with tears, quatrefoils, and hearts in presses: English, ?15thC. (© The British Museum)

10.8 Girl holding flower labelled apriel: ‘print’ engraved base of silver bowl, English, early 15thC. (© The Museum of London)

10.9 Gold ring-brooch with inscription beginning IEO SUI FERMAIL: English or French, 13thC. (© The British Museum)

10.10 Rose branch and inscribed banderole: carved wooden capital. (© Alte Burse, Tübingen: photograph courtesy of Manfred Grohe)

10.11 Lovers playing chess, inscribed with couplet: leather shoe upper, Dutch, c. 1400. (© Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden)

10.12 Man wearing hat with badge (enseigne): oil painting on panel (detail), Jan Gossaert, 1520s. (© Sterling and Francine Clark Institute, Williamstown)

10.13 Silver-gilt bridal crown with openwork inscription, trewelich: South German, mid-15thC. (© Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nürnberg)

10.14 Violets growing on a grassy bank: lead badges, upper example inscribed veolit in maye lady, English, 15thC. (Above © Museum of London. Right: private collection. Photographs courtesy of Brian Spencer)

10.15 Heart-in-press, 16thC painting of tournament horse’s trapper, 1512, German.

10.16 Lady arms her kneeling knight, enamelled harness-pendant, 15thC, Spanish. New York, Metropolitan Museum, LC-043-454-001.

10.17 Lovers beneath tree and amuletic inscription, enamelled harness-pendant, 15thC, Spanish. New York, Metropolitan Museum, LC-043-432-001.

Ornament to Chapter 11: man gropes hen (hennetaster): stall-elbow, Kempen, c. 1500. (Photograph courtesy of Elaine Block)

11.1 Bearded lady spinning: manuscript miniature, Topographia Hibernia, English, early 13thC. (© The British Library. Ref: BL, Royal MS 13. B. VIII, f. 19)

11.2 a and b Young woman spinning (left, with flap down, snake between her legs; right, with flap raised): pen-and-ink lift-the-flap drawing, German, early 16thC. (© Staatsbibliothek, Berlin. Ref: MS germ. qu. 718, f. 65v)

11.3 Battle for the Breeches: dotted print, Keulenmeister, Upper Rhine, 1460s. (© The British Museum)

11.4 Man in apron washing up: misericord supporter, Beverley Minster, 1520. (Photograph: author’s collection)

11.5 Old woman binds devil to cushion: stall-elbow, Hoogstraeten, 1532x48. (Photograph courtesy of Elaine Block)

11.6 Title-page woodcut, Smyth whych that forged hym a new dame, London, c. 1565. (© Bodleian Library, Oxford)

11.7 Phyllis riding Aristotle: bronze aquamanile, Mosan, c. 1400. (© Metropolitan Museum, New York)

11.8 Devil appears between ‘horns’ of woman’s headdress: misericord, Minster-in-Thanet, c. 1410. (© University of Manchester: photograph courtesy of Christa Grössinger)

11.9 Woman combing her hair sees devil’s arse in mirror: woodcut, Ritter von Thurn, Basel, 1493.

Ornament to Chapter 12: legged phallus approaching legged vulva: lead badge inscribed PINTELIN, Dutch, 1325x75. (Private collection: photograph Cothen*)

12.1 Young woman making anasyrma gesture: pipeclay figurine, ?Cologne, 15thC. (Photograph courtesy of Brain Spencer)

12.2 Phalli carrying crowned vulva on litter: lead badge, Dutch, 1375x1425. (© Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum, Rotterdam: photograph Cothen*)

12.3 Vulva-pilgrim: lead badge, Dutch, 1375x1425. (Private collection: photograph © Stichting Middeleeuwse*)

12.4 Ballock-knife/-dagger: English, 15thC. (© Museum of London)

12.5 Woman drinks from phallovitrobolus: misericord supporter, Bristol, 1520. (Photograph: author’s collection)

12.6 Witch magically removes another penis: woodcut (detail), Pluemen der tugent, Augsburg, 1486. (© Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich)

12.7 Death and the lascivious couple: engraving, Hans Sebald Beham, 1529. (© Ashmolean Museum, Oxford)

12.8 Bird pecks glans of phallus-animal: lead badge, Dutch, second half of 14thC. (© Bureau Oudheidkundig Onderzoek Rotterdam: photograph courtesy of H.J.E. Van Beuningen)

12.9 Phallus-bearing tree: pen-and-ink drawing, ?German, late 15thC. (© Topkapi Sarayi Müzesi Sultanahmet, Istanbul)

12.10 Woman picks apple, man cups her breasts, older woman looks on: tapestry (fragment), Basel, c. 1480. (Private collection: photograph courtesy of Galerie Arts Anciens, Montalchez)

Ornament to Chapter 13: man exposes bottom at viewer: stone label-stop, Cley, ?14thC. (Photograph courtesy of Charles Tracy)

13.1 Friar evacuates devil: misericord, Windsor, c. 1480. (Photograph courtesy of the Dean and Canons of Windsor)

13.2 Dukatenmensch,: wooden statuette, Goslar, 1494. (Photograph courtesy of Schoening Verlag, Lübeck)

13.3 Eulenspiegel ‘beshits the roast’: woodcut, Eulenspiegel, Strasbourg, c. 1510.

13.4 Peasant observes Neidhart finding the violet (Veilchenschwank): woodcut, German, late 15thC.

13.5 Man stirring excrement: pen-and-ink drawing, Proverbes en Rimes, Savoie, late 15thC. (©Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore)

13.6 Bum in the oven: Manuscript miniature, (Marcolf), Hours of Marguerite de Beaujeu, Franco-Flemish, c. 1320. (© Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. Ref: MS M. 754, f. 3v)

13.7 Boys playing ‘cock-fighting’: misericord supporter, Windsor, c. 1480. (Photograph courtesy of the Dean and Canons of Windsor)

13.8 Man bellows ape’s bottom: misericord, Great Malvern, c. 1480, (Photograph: author’s collection)

13.9 Man urinates into winnowing-fan, misericord carving, 1522, Champeaux, France.

* Stichting Middeleeuwse Religieuze en Profane Insignes, Cothen: photograph courtesy of H.J.E. Van Beuningen.

Colour Plates

1. Robert of Knaresborough ploughs with stags: stained glass window (detail), St Matthew’s Church, Morley, c. 1482. (Photograph courtesy of Harrogate Museums and Arts)

2. Flemish proverbs: tapestry fragment, Flemish, late 15thC. (© Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston)

3. Composite phallic head, inscribed in retrograde TESTA DE CAZI: maiolica plate, Casteldurante, 1536. (Private collection)

4. Landgraf Ludwig I von Hessen and his arms hanged upside down: painted manuscript Schandbild, German, 1438. (© Institut für Stadtgeschichte, Frankfurt)

5. Sow soils seal of Herzog Johann von Bayern-Holland: painted manuscript Schandbild, German, c. 1420.

6. Netherlandish Proverbs, Bruegel the Elder, oil on canvas, 1559. (© Bildarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin)

7. Heinrich von Veltheim depicted flaying a dead horse: painted manuscript Schandbild, German, 1490s. (© Stadtarchiv, Göttingen)

8. Abbot of Minden in fool’s hood rides backwards on ass, another monk hangs from gallows: painted manuscript Schandbild. (© Niedersächsisches Staatsarchiv, Bückeburg)

9. Fool embraces woman: painted wooden towel-rail, Arnt van Tricht, Kalkar, 1530s. (© Museum Kurhaus, Kleve: photograph courtesy of Annegret Gossens)

10. Fool-bishop inside initial ‘D’: manuscript miniature, English, first half of 13thC. (By permission of the Warden and Fellows, New College, Oxford. Ref: New College MS 7 f. 142r)

11. Der Busant: tapestry fragment, Strasbourg, late 15thC. (© Metropolitan Museum of Art)

12. Man grimacing: oil on panel, Flemish, early 16thC. (© Galerie Wittert, Université de Liège)

13. Exemplum of man, fox, serpent: manuscript miniature, Rutland Psalter, English, c. 1260. (© British Library. Ref: BL, Add. MS 62925, f. 110)

14. Cassandra of the Nine Female Worthies: oil on panel, Lambert Barnard, Amberley Castle, 1530s. (© Pallant House Gallery, Chichester)

15. Solomon and Marcolf: manuscript miniature, Ormesby Psalter, English, early 14thC. (© Bodleian Library. Ref: MS Douce 366, f. 72r)

16. Riddle, test of resourcefulness: manuscript miniature, Ormesby Psalter, English, early 14thC. (© Bodleian Library. Ref: MS Douce 366, f. 89r)

17. Petrified maidens’ dance: manuscript miniature, marvels of the East, English, early 12thC. (© Bodleian Library. Ref: MS Bodl. 614, f.81v)

18. Lovers grafting clasped hands of fidelity, and ‘daisy oracle’: tapestry (detail), Strasbourg, c. 1430. (© Historisches Museum Basel)

19. Love-magic ritual (Liebeszauber): oil on panel, Cologne, late 15thC. (© Museum der bildenden Künste, Leipzig)

20. Girl binds forget-me-not garland: oil on panel, Hans Suess von Kulmbach, c. 1510. (© The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

21. Venus adored by famous lovers: painted birth-salver (desco da parto), Florence, first half of 15thC. (Musée du Louvre, Paris: photograph © Réunion des Musées Nationaux, courtesy of Gérard Blot)

22. Assault on the maiden’s castle: pen-and-ink drawing with colour-wash, Flemish, c. 1470. (Private collection, São Paulo: photograph courtesy of José Mindlin)

23. Knight of the drooping lance: pen-and-ink drawing with colour-wash, Flemish, c. 1470. (Private collection, São Paulo: photograph courtesy of José Mindlin)

24. His key too small for her lock: pen-and-ink drawing with colour-wash, Flemish, c. 1470. (Private collection, São Paulo: photograph courtesy of José Mindlin)

Foreword to the 2025 Edition

It is a curious experience to be invited to revisit work published some two decades ago! One is gratified to think it has been deemed an exercise still potentially profitable.

There are corrections to be made, of course – despite one’s best efforts, the occasional error of fact, the emphases of interpretation one might now wish to have toned down – or, indeed, up. But it is also an oddly personal reckoning. Have one’s words stood that famously chronological examination, the ‘Test of Time’? And never mind the criticisms of others, do they survive one’s own?

I think now – some two decades after the event – that my hopes for the book were that it should prove an ideal title to appear on the reading-list of students embarking on a Medieval Studies course – not a course in Medieval Art History (supposing such a course should still exist) – just as a general background book, but also as a Don’t-believe-everything-the-classic-books-tell-you-about-the-Middle-Ages sort of book – and yet, I hope, a book far from frivolous. I’ve no reason to believe it appeared on any student’s reading-list – ever. (But eager to be disabused!)

Rather than write what would, in effect, be a completely new book, I have chosen to add the new material to the end of each chapter. This new text attempts to update recent research and adds occasional new motifs which have since come to my notice. It cannot, of course, be a synthesis of the last two decades’ work in medieval studies as they pertain to art history; it must inevitably be only an idiosyncratic update referring only to those books, articles and discoveries that I have happened to notice in areas of interest to me – but peppered with a few new hobbyhorses of my own.

It seems counter-intuitive, but in fact, the corpus of medieval art and artworks is always growing! The enthusiasm for metal-detecting – in Britain especially – has yielded many ‘new’ medieval objects, and in particular, the copper-alloy seal-matrices with their often quirky legends and fascinating devices. New wall-paintings too continue to emerge, shyly, or – in the case of those in the Languedoc, rudely – from under the centuries of whitewash and overlay. And just when one thought that the inventory of all late medieval illuminated manuscripts was closed, along comes the spectacular Macclesfield Psalter! Even – inevitably the year after the book was published – new panel paintings appear, such as the extraordinary late fifteenth-century Allegory of Love attributed to the confusingly-named (as he worked in Antwerp) Master of Frankfurt. And, as ever, the Dutch lead badges continue to astonish – surrealism avant la lettre! But nor does scholarship stand still – even long familiar artworks can be reclaimed, re-identified and re-interpreted in the light of new knowledge.

My aim in 2002 was to present a somewhat different picture from that found in the generality of books on medieval art, one that did not ignore huge areas of medieval culture, and one that I hoped would prove a corrective to what I regarded as the long-standing, distorted perception of medieval art.

The exponential growth of the internet in those past two decades has seen the publication of various corpora and databases, and now every major museum and gallery, and most minor ones too, has a searchable website, and other online blogs and platforms have appeared on which much excellent work is published (and much dross too, of course).

In those past two decades my own interests have moved forward chronologically too, and I am currently absorbed by the extraordinary iconographic wealth of early modern alba amicorum [‘friendship books’] – still all but unknown in Britain – an iconography which, of course, continues many of the motifs first found in the late Middle Ages, as I am at pains to point out in what follows, in what I find I still tend to think of as The Other Middle Ages.

Malcolm Jones

Bucharest

November 2024

Foreword to the 2002 Edition

In the Royal Society of Antiquities, a lofty hall off the courtyard of the Royal Academy, Malcolm Jones was showing slides of winged penises, flying vulvas, belled cocks, pudenda on stilts, and other symbols of vigour and fertility; he was accompanying the slides with a learned commentary on the emblems, on their associated puns, proverbs, and possible significance and uses. From this material, he then moved on to sows and donkeys spinning thread, to lubricious widows, and other misogynist motifs; this was followed by a look at some capering wild men or wodehouses, and a short enquiry into fantasies associated with their hairy bodies.

It was the first time that I had heard Malcolm Jones speak, and I was there because I’d read an extraordinarily rich and surprising article on sexual culture in the Middle Ages published in the journal Folklore. The evidence he was presenting to his audience of Antiquaries focused on medieval lead badges, die-cast metal artefacts, which have been buried for centuries: many examples have recently been dredged up from the tidal Schelde estuary in the Netherlands. The invention of the metal detector, and the perseverance of anoraked enthusiasts in the mudflats, have made possible the discovery of a new contemporary treasure hoard. These cheap souvenirs from pilgrimage sites, akin to the contemporary lapel or hitchhiker’s rucksack badge, these emblems have revealed new depths to the fantastical, bold, rude and secular mentalité of the ordinary man and woman.

The talk Malcolm was giving that day was scholarly, serious, and highly original. But it was also, inevitably, funny: there is no other response to these images and punning devices than laughter. Laughter is interesting in its complexity of response: a release from embarrassment, a recognition of rudeness and outrageousness, as well as a kind of shock that the unspeakable has been spoken, the obscene brought in from the wings to take centre stage. In this packed and fascinating book, The Secret Middle Ages, Malcolm Jones has mustered a crowd of many more star witnesses, an exuberant and outspoken host of characters – burlesque saints, wise fools (and ribald ones), hairy anchorites, Englishmen with tails, donkey-headed dunces, and a huge and entertaining case of animal characters who bridge the world of the classical fable and the Victorian children’s tale. These figures are compacted of stories, and communicate symbolically, through sign, gesture, allegory, wordplay, and dense, literary allusion. They provide an iconic thesaurus of ‘the other Middle Ages’, as the author calls his focus of interest (c. 1100–1550). Together they colour in a picture of a less repressed, less courtly, less institutionalised, more eclectic, and above all less Christian complex of thinking and feeling, connecting to non-Christian antecedents. What Chaucer in English, Boccaccio in Italian, and, later, Rabelais in French, explore through their storytelling, comic vision and verbal virtuosity, many artists using every kind of form – biscuit moulds, misericords, valentines, crockery, leather, mirrors and body language – also contain and heavenward-reaching spires of Gothic cathedrals, penitential superstition and ignorance, are shutting their faculties to a lively, and very different history.

Traditionally, the overlooked margin has been the place where the subversive gesture, the impious (often devilish) doodle, the blasphemous vignette have been confined, but Malcolm Jones sweeps them into plain sight, as part of a larger record of imaginative order imposed on experience. Also, unlike analysts who use the psychological model of repression to explain medieval secular imagery, he finds impious energies expanding throughout the social sphere, nor only fuelling a counter culture identified with the plebeian, lower orders. Mikhail Bakhtin’s celebrated study if Rabelais developed the idea of the carnivalesque in order to understand popular forms of expressions that involve unruliness, mockery, and insubordination. The generous and wide-ranging repertory of motifs and objects offered here by Malcolm Jones effectively puts a question mark against this model of inversion, of occasional eruptions and explosions of the people’s voice. His wonderful mass of lore, from the language of flowers to the vision of Cockaigne, from the encoding of sexual knowledge to the dirty jokes, shifts the secular temper of the times from the periphery and spreads it more widely. His material consequently also disturbs easy acceptance of the carnivalesque as medieval authority’s method of containing rebellion and maintaining social cohesion. It reveals the plurality of means of expression in medieval society, a looser political stranglehold on the tendencies and pleasures of the imaginary, and widespread and deeply embedded ways of meaning and communication held in common.

Much of the imagery has become unfamiliar to contemporary receivers, because we are ignorant of the sources, and cut off from the circulation of their ideas – partly as a result of aesthetic patrolling of medieval profanity. But recovering these meanings, discovering the things that aroused a man or a woman in fifteenth-century York, or that made them laugh, or stirred their derision, can reconnect us to the past, even if we do not experience the same things in the same way. As Malcolm Jones points out, it is very odd indeed that in this country, which is so rich in different local traditions, and so committed to historical understanding, so little research into the vernacular cultures of the past is being done (his university, Sheffield, being one of the very few to offer a course of stidy into folklore).

‘Folklore’ was the term coined in 1846 to describe the common stockpot of customs, beliefs, images, songs and sayings of a place and the people who live there. In an age so riven by questions of belonging and unbelonging, these elements – these commonplaces of a culture – give texture, distinctiveness and vitality to memory, individually and socially. But to be a folklorist in these islands somehow condemns you to be seen as a kind of train-spotter, jigging Morris bells, and quaffing real ale. Yet the stories, images, proverbial wisdom collected and discussed here could never be described as nostalgic or cosy, but go to the heart of many matters, including difficult, disturbing areas of mistrust, xenophobia, intolerance, misanthropy, as well as sexual conflict.

The Secret Middle Ages contains a unique and remarkable archive of illustrations, of unfamiliar artefacts and pictures, never gathered together before, and the result of years of unrivalled intellectual archaeology. It really would be impossible to credit the complexity and duration of the work involved in such a record – it requires finding, travelling, noticing, identifying, collecting and obtaining a photograph of every item. The publishers are also to be congratulated, along with the author, on these generous reproductions in colour and black and white. Every image here counts: each one gives rise to a journey, a journey through stories, fantasies, assumptions, values; throughout, Malcolm Jones is a most learned and spirited guide, a vivid storyteller and a lexicographer, an iconographic decipherer and a widely versed translator. He’s a living descendant of those prodigal narrative information gatherers of the Middle Ages, those indefatigable chroniclers and encyclopaedists like Bartholomaeus Anglicus, Honorius of Autun, Gervase of Tilbury, and Petrus Comestor (‘Peter the Eater’, so called because he consumed such mighty helpings of knowledge), who also produced books of wonders and curiosities and of lost knowledge of flora and fauna, and made sticks and stones come alive and speak across time.

Marina Warner

June 2002

Preface

This book deliberately sets out to present only half the picture, or half the story, of late medieval art. But it is a half that has been missing, very much the other half. It was born of my frustration with existing general books on medieval art, which seemed to me only ever to present a partial picture consisting of the selfsame artworks that I had seen in all the other ‘art’ books, if arranged in a slightly different order – clearly the stock of medieval art was both very religious, and very limited. The reasons for this curious imbalance are bound up with the history of art history. At the risk of gross oversimplification, the history of the discipline is the history of connoisseurship, and connoisseurs were traditionally interested in ‘Old Masters’ and the Renaissance which, of course, ‘began’ in Italy, and sounded the death-knell of the benighted Middle Ages. It was the Italians who were first classified as Old Masters (and so it has largely remained) although later, and grudgingly, certain Northern European artists were admitted to the charmed circle, mainly the Flemish and the German, but by now, if, as conventionally, we end the Middle Ages in 1500, these ‘parvenus’ were for the most part, safely post-medieval.

While mainly concerned with paintings, connoisseurs were also interested in a mysterious, ill-defined (but always expensive) class of item known as the ‘object of vertù,’ examples of which they sold to each other from time to time (and still do) via the salerooms of the major auction houses. The connoisseur reserved the extreme of his contempt for objects which could only be called ‘archaeological’, unless, of course, they were ‘classical’, or – at a pinch – if not classical, at least fashioned from gold or silver. It would be all too possible (but too depressing) to reconstruct the traditional art-historical hierarchy of medieval art. At the very pinnacle of the pyramid would be paintings – preferably on panel – of the Italian Renaissance – preferably Florentine – and at the bottom, slithering around in the slime (for is it not, after all, quite literally their provenance?) the badges of lead to which I devote so much space here.

This is, of course, a caricature, but such historically-derived attitudes to medieval art, however unconscious, still underlie much of the modern perception of the art of the European Middle Ages. Not only have certain periods and regions been unthinkingly privileged in past decades, but, so too, have particular media, and particular subjects – as if, absurdly, a Florentine painting of the Virgin and Child by a named artist is somehow intrinsically more valuable to art history, than a German clay cake-mould of a peasant ‘brooding’ eggs by an anonymous artist. A recent magnificently produced and authoritative book on medieval jewellery omitted to discuss the bulk of the humblest lead jewellery which is, as I suggest here, both of disproportionate importance to our understanding of medieval culture as a whole, and all but unstudied, and would have benefited especially from being studied by an author so plainly familiar with the more pretentious pieces. Gems and precious metals may dazzle the eye – as, indeed, they do in that book’s sumptuous colour plates – but often advertise little more than the predictable, conspicuous consumption of the elite; a lead badge or brooch, on the other hand, though it may look like some tawdry fairing, may be of more iconographic significance than a cofferful of royal jewels. In the study of the applied arts of the Middle Ages, and sad to say, in England above all, one is still too often forced to the conclusion that ancient snobberies, of the sort which have historically divorced the connoisseur’s objet d’art from the archaeologist’s artefact, and high art from folk art, are still alive and well and living in our national museums and galleries.

In this light, it is entirely predictable that although the personal seals of relatively humble English men and women (including some known to have been of villein status) make up some 80 per cent of all known seals surviving from medieval England, ‘they have been far less studied than the other one-fifth’ of aristocratic type.1 And yet the situation is not quite so bleak as the influential Dutch cultural historian of the Waning of the Middle Ages, Johan Huizinga, believed, writing just after the First World War:

… we only possess a very special fraction of it [sc. art]. Outside ecclesiastical art very little remains. Profane art and applied art have only been preserved in rare specimens. This is a serious want, because these are just the forms of art which would have most revealed to us the relation of artistic productions to social life.2

Like so many such generalisations, this is both true and untrue, true only in part, but not even entirely true at the date that it was written. ‘Profane’ and applied art have not only been preserved in rare specimens, European museums are full of such specimens, but art historians have only rarely deemed them worthy of study, and therefore the great bulk of such material remained unpublished – certainly at the period in which Huizinga was writing – though it is to be hoped that now, at long last, the situation is being somewhat redressed, not least by the publication of catalogues of the lead badges which feature so prominently in the present book and which, ironically, were later to surface in such profusion from Huizinga’s native soil.

In 1988, writing ‘On the State of Medieval Art History’ in The Art Bulletin, Herbert Kessler devoted a mere five lines (in an article running to some twenty pages) to ‘secular art’, the subject of this book:

Even in the secular realm, medieval art was forcefully conventional. Although considerably greater freedom for innovation existed there than in religious production, secular art, too, was governed by the requirement of accuracy in recording secular history.

Admittedly, this generalisation was written by a specialist in medieval religious art, but the absurdly thin coverage of studies of medieval secular art to 1988 – only one book and two articles being footnoted – speaks volumes. It is my hope that this book will take its place alongside those written both before and since 1988, so that never again will it be possible for anyone purportedly reviewing ‘The State of Medieval Art History’ to have done with ‘the secular realm’ in five lines!

I suggest that it is not only that religious art has been privileged for historical and even less worthy reasons, but that – if I dare put it thus baldly – many writers on this period simply do not know the range of visual material that is out there. I hope there are many illustrations in the present book that are unfamiliar to most readers, and even a few that are unknown to experts in the field. Of course, there must be some that are familiar, when the argument requires them – I am not trying to present novelties for novelty’s sake – but I trust the previously unknown images reproduced here will, by their very publication, become better known to students working in this area, and I look forward to seeing them reappear in others’ books.

Hence my title. This material is not really ‘secret’, of course, though one might be forgiven for thinking that much of it was. With the exception of those items literally kept secret from us by the ground which has covered them until their recent excavation, all this material has long been available in museum, archive, and gallery collections – nor, for the most part, can we hide behind the excuse that it was uncatalogued. But there is a sense in which that side of the Middle Ages I write about here has been ‘secret’, for it has not been made public, not been published, and thus remained, as it were, always in shadow – even suspect. With this book I hope to have cast a little light on some neglected aspects of the era.

Nor is this entirely a book about art. There are many aspects of medieval, as of modern, art which are part of the visual culture of the period, though they may rarely ever have been consciously depicted. We hear, for example, of humiliating punishments to which enemies of the nation or of society were subjected, punishments whose visual impact was often an important component of their efficacy – such evidence from chroniclers and others is made use of in Chapter 5. But much art (by anyone’s definition) has simply not survived the passage of the intervening centuries, and so, to recover some of this ‘lost’ material, this book makes full use of inventories and other descriptions of lost work.

In what follows, I have deliberately avoided using such terms as ‘popular art’ or ‘folk art’ in my attempt to redress what I see as an imbalance in the modern representation of medieval art, because such terms seem to me to be just as potentially damaging in the opposite direction, implying that such art was not also visible to the upper echelons of society. Similarly, although I concern myself principally with art which is not overtly religious in its subject matter, it would be foolish and betray a deeply erroneous understanding of medieval realities, to style such work ‘secular’, however oddly the depiction of genitals and buttocks, for instance, may sit with our early twenty-first-century understanding of what is appropriate to church decoration. It is perhaps needless to add, that the aesthetic appeal of any of the items I discuss, I regard as accidental, and would ideally purge myself of all such irrelevant estimations – if I could.

I think it only right to define some of the parameters of my subject. Chronologically, by ‘medieval’, I normally mean late medieval, say, roughly 1200–1550 – ‘medieval’ attitudes and motifs are not all swept away in one cleansing rush of Renaissance fresh air, of course, so I feel free to extend my Middle Ages well into the sixteenth century. Geographically, I focus on England, as it is the English material with which I am most familiar, but I am also anxious to show that England was by no means as much an island culturally as has sometimes been assumed, but shared in many European fashions. Occasionally I treat of continental motifs for which I know of no medieval English reflex, if they seem to me to be of sufficient intrinsic interest in illuminating medieval mentalité.

In terms of genre, I have tried not to privilege manuscripts and other graphic works at the expense of artefacts. On leaving university a formative year spent in what was then the British Museum’s Department of Medieval and Later Antiquities, has left me with an enduring affection for objects. The lead badges, in particular, constitute a major ‘new’ category of material that cannot be ignored by historians of this era any longer.

I must also admit, however, that, for all the foregoing, this is a book without a thesis – unless it is that I claim there is a wealth of fascinating material that needs to be considered before we think – let alone dare to declare – we know what medieval art is. It is my hope that I have presented as much, and as representative a sample, of that ‘secret’ art as my knowledge, and my indulgent publishers, will allow. I feel no shame in submitting to the world a survey of ‘the rest of’ medieval art, without arguing any sort of case beyond its necessary publication – indeed, I believe that the case of medieval art has been argued hitherto with only a very partial and unrepresentative sampling of the evidence. I have read rather too many books which have taken a ‘global’ overview of the Middle Ages or medieval art, and shown us a Brocéliande, magical only in so far as it is extraordinarily more than the sum of its trees. I shall not be unhappy if this present book identifies rather too many trees than might be happily accommodated in any self-respecting wood. And if my wood should prove invisible, I flatter myself that the questing reader may at least make out some of its major denizens through the gloom of trees too densely packed – I leave it to others to discern the wood in its entirety. I am very suspicious of over-arching ‘unified field’ theories of anything – let alone medieval art. Where is our humility? Is it reasonable for any modern to claim sufficient knowledge of the medieval era as to be able to ‘pluck out the heart of its mystery’? We are all gropers in the darkness, and if all our little illuminations should coalesce so far as to cast an uncertain light on the subject of our study, that is the best we may reasonably hope for.

Any book that purports to be about culture must also to some degree be about the language in which that culture expresses itself. I write as a student of language and of the English language in particular. One cannot study the English language without becoming familiar with the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), and that deepening familiarity can breed only awe. One cannot use the OED over the decades, as I have done, without becoming aware of what a great monument it is, both to our language and to English nineteenth- and twentieth-century scholarship. That it was first compiled in a pre-computer age is hard for us now to believe. That it is now already available on searchable CD-ROM, and increasingly so on the Internet, makes it easily the single most important resource for the study of our language. The OED is an anthology of English literature too, of course, and, if I have beautified myself with its feathers freely, I hope I have remembered to acknowledge their origin – discerning readers will at least be clear that what may appear as my own encyclopedic reading is, in fact, that of the OED’s many readers, past and present. Without this passe-partout to our (and many other people’s) language, the present book would be a poorer thing than it is.

Lastly, I hope this is a book with ‘attitude’ – doubtless one which, with the passing of time, I shall wish I had tempered – but a book in which, though I pay lip-service to a proper stylistic objectivity, I have managed to forget my scholarly pretensions sufficiently often to seem like a person interested in what he is writing about. While I trust I have not abandoned gravitas completely, I believe it should be possible to write interestingly and seriously, and still sound like a human being trying to get to grips, however imperfectly, with the puzzles and contradictions of an era that is both so like and so unlike our own.

Acknowledgements

The proper acknowledgement of my debt to others’ work would make a chapter in itself. We moderns are all pygmies standing on the shoulders of giants, and I take this opportunity to name a few of the giants in my own pygmyhood.

This is a book which has had an unnaturally long gestation. It should have been written ten years ago – though would, of course, have been rather different if it had. The industry of friends and colleagues has frequently put me to shame over the past decade, and frequently, in response to their polite enquiries, led to embarrassing mumblings about working on a book. I hope that the present volume will to some extent absolve me in their eyes for this shocking indolence.

Seminal in the development of my own understanding of the areas discussed in this book, was Lilian Randall’s Images in the Margins of Gothic Manuscripts – an eye-opener, if ever there was one – and it is no exaggeration to say that my discovery of that book’s riches some thirty years ago, led directly to the present book, and to establishing my interests in iconographic investigation per se. More recently, another American scholar, Ruth Mellinkoff, has published a superb and handsome volume, Outcasts: Signs of Otherness in Northern European Art of the Late Middle Ages (Berkeley, 1993), which I wish I had written, and I thank her for her friendship and generous sharing of her knowledge.

The late Michael Camille’s books, which have anticipated some of the areas addressed here, have been a constant inspiration, and not least for their written style – a breath of fresh air! – and I have been grateful for his continued encouragement of my own work. The Medieval Art of Love (London, 1998) is typical of his ability to surprise us with new and significant images of artefacts especially, and it is an example I have tried to adopt here. It is a matter of deep regret his tragically early death means I can no longer present him with a copy of this book, but I am hopeful that it would have earned his approval.

It will be clear from what follows that two media in particular have engaged my attention, the misericord and the lead badge. Any book I might once have written on misericords has now been rendered superfluous by the appearance of Christa Grössinger’s excellent and superbly illustrated survey, The World Turned Upside Down. English Misericords (London, 1997), and I am grateful both to her and to my fellow ‘misericordians’ who have gathered around the indefatigable Elaine Block and her journal The Profane Arts, and especially to Kenneth Varty, doyen of renardiens – and one of the two people professionally obliged to read my doctoral thesis. On first moving to my present home in Derbyshire, it was to Charles Tracy’s expertise I turned for advice on the identification and date of a piece of carved woodwork that I had noticed, and his willing assistance soon led to a joint article and an enduring friendship, and I thank him for his continued faith in me.

In this country, lead badges have been the province of one man, Brian Spencer, and his generous friendship and scholarship down the years have taught me so much, and revealed so many embarrassing gaps in my own knowledge. In the Netherlands, H.J.E. Van Beuningen has been the pre-eminent collector and promoter of the importance of these artefacts and it is thanks to his kindness and enthusiasm that I have had the privilege of working with the badges in his collection and access to the many photographs of them reproduced here.

It is no accident that during the unconscionably delayed appearance of this book I have become acquainted (and sometimes friends, indeed) more with museum curators than with librarians. John Cherry, who has just retired as Keeper of what was the British Museum’s Department of Medieval and Later Antiquities (now ‘rebranded’ as Medieval and Modern Europe), has been unfailingly helpful and friendly to my often naive enquiries. I have frequently envied and sought to emulate his modestly priced, yet profusely illustrated, Medieval Decorative Art (London, 1991).

Latterly, my footsteps have bent towards the Museum’s Department of Prints and Drawings, where Sheila O’Connell has patiently explained the nuances of print-production to me and facilitated access to that Department’s rich holdings. It is rare that an entirely original work appears, but such indeed was The Popular Print in England 1550–1850, and it was my privilege to have become acquainted with her during the preparation of that ground-breaking volume. It is a sorry indictment of previous English scholarship in this area, but perhaps not so surprising given the shameful tradition of the denigration of the vernacular in English art history, that we had to wait until the final year of the twentieth century for such a necessary survey.

In case I may appear churlishly dismissive of librarians, I want to single out here the Derbyshire County Library Service which, before I had regular access to a university library, supplied me with untold volumes from all over the world – though the Director of Library Services was once moved to tell this particular rate-payer precisely how many books and articles he had on order. The friendly staff of my local public library in Matlock were always indulgent to my requests and I am happy to be able to thank them here in print.

When I first came across J.B. Smith’s article, ‘Whim-whams for a goose’s bridle’ in the journal Lore and Language, I knew at last that I was not alone, and was confirmed in my belief that it was indeed possible to pursue the sort of thing I was interested in at a serious level, and I have spent the time between trying, however inadequately, to approach the level of his scholarship.

On first looking into Lutz Röhrich’s Lexikon der sprichwörtlichen Redensarten, the scales dropped from my eyes, and I understood in a flash the significance of the proverbial in medieval art, and a growing acquaintance with that magisterial work led me to a proper appreciation of the proverb – an appreciation that quite inevitably introduced me to my friend, Wolfgang Mieder, whose own industry is as proverbial as his generosity.

In what often seems the all-too-insular world of English scholarship, I am especially happy to have this opportunity to acknowledge a general debt to Dutch and German cultural historians, who have had the breadth of vision that has been granted to few English scholars (with the honourable exception of Peter Burke). I refer, in particular, to Herman Pleij, and the encyclopedic Paul Vandenbroeck and Christoph Gerhardt, to name only the most important to my own researches. I wish I had more room to expatiate on their individual contributions to the history of European culture, but their monuments are their works and they do not need my poor praise.

Finally, as one who aspires to be worthy of the title of folklorist and as perhaps the only individual in England employed full time to pursue that calling, I cannot close these Acknowledgements without allowing myself some observations on the state of folklore in England, for my native country is surely unique among the nations of Europe, of the world indeed, in officially despising its folklore. With all too few exceptions, certainly in recent decades, its intelligentsia have disdained to acknowledge this discipline at all, in fact have sought to belittle and ridicule it. Notwithstanding this establishment onslaught, a number of independent-minded spirits have found succour in the arms of the Folklore Society, and my membership of that brave organisation has introduced me to many experts in subjects for which bibliographies do not yet exist, and whose constant support and encouragement bolstered my determination to bring the present project to fruition.

When every other nation in the world has a centrally funded institute of its national folklore, I marvel that the country of my birth should be so scornful of its indigenous, immemorial culture that it has none. But here – inevitably – I come to acknowledge my debt to the University of Sheffield, and more particularly to my colleague and friend, John Widdowson, founder of the university’s National Centre for English Cultural Tradition, a title which, however – sadly, if predictably – does not imply national funding (I avoid using the weasel-word ‘heritage’ which has now been hijacked as the current establishment euphemism for theme-park Britain).

It behoves me too to commend the enlightened policies of both Sheffield University, which granted me a semester’s Study Leave in order to finish this long unfinished book, and of the Arts and Humanities Research Board, which was prepared to double it. I am also most grateful to the British Academy for awarding me a small research grant, which has subsidised the publication of the greater part of the images reproduced here.

Matlock, April 2002

Conventions and Abbreviations

I adopt the archaeologist’s useful – though it seems far from universally recognised – convention that a medial ‘x’ between two dates indicates that the item was manufactured (or event occurred) at some unknown date between those termini – where a similarly positioned hyphen indicates duration of composition or occurrence. Frequently cited reference works, some of which appear in the body of the text, are abbreviated thus:

DMLBS

Dictionary of Medieval Latin from British Sources.

EPNS

English Place Name Society.

Geisberg

M. Geisberg, Der deutsche Einblatt-Holzschnitt in der ersten Hälfte des 16. Jahrhunderts (Munich, 1923–30; rev. W.L. Strauss, New York, 1974).

HP1

ed. H.J.E. Van Beuningen and A.M. Koldeweij, Heilig en Profaan. 1000 Laat-middeleeuwse insignes uit de collectie H.J.E. Van Beuningen (Cothen, 1993).

HP2

ed. H.J.E. Van Beuningen, A.M. Koldeweij and D. Kicken, Heilig en Profaan 2. 1200 Laat-middeleeuwse insignes uit openbare en particuliere collecties (Cothen, 2001).

IMEV

Index of Middle English Verse.

LSR

ed. L. Röhrich, Das große Lexikon der sprichwörtlichen Redensarten (Freiburg, 1991).

MED

ed. H. Kurath et al., Middle English Dictionary (Ann-Arbor, 1952–2002).

Motif-Index

S. Thompson, Motif Index of Folk Literature (Bloomington, 1966).

MOL

B. Spencer, Pilgrim Souvenirs and Secular Badges (London, 1998).

ODEP

F.P. Wilson (ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of English Proverbs (3rd ed., Oxford, 1970).

OED

The Oxford English Dictionary, second ed. CD (Oxford, 1994).

PMLA

Proceedings of the Modern Languages Association (of America).

Randall

L. Randall, Images in the Margins of Medieval manuscripts (Berkeley, 1966).

Schreiber

W.L. Schreiber, Handbuch des Holz- und Metallschnittes des xv Jahrhunderts (Leipzig, 1926–30).

TPMA

ed. Kuratorium Singer der Schweizerischen Akademie der Geistes- und Sozialwissenschaften, Thesaurus Proverbiorum Medii Aevi. Lexikon der Sprichwörter des romanisch-germanischen Mittelalters (Berlin and New York, 1995–).

Whiting

B.J. and H.W. Whiting, Proverbs, Sentences and Proverbial Sayings from English Writings, Mainly before 1500 (Cambridge, Mass., 1958).